Second-chance Commode

Introduction

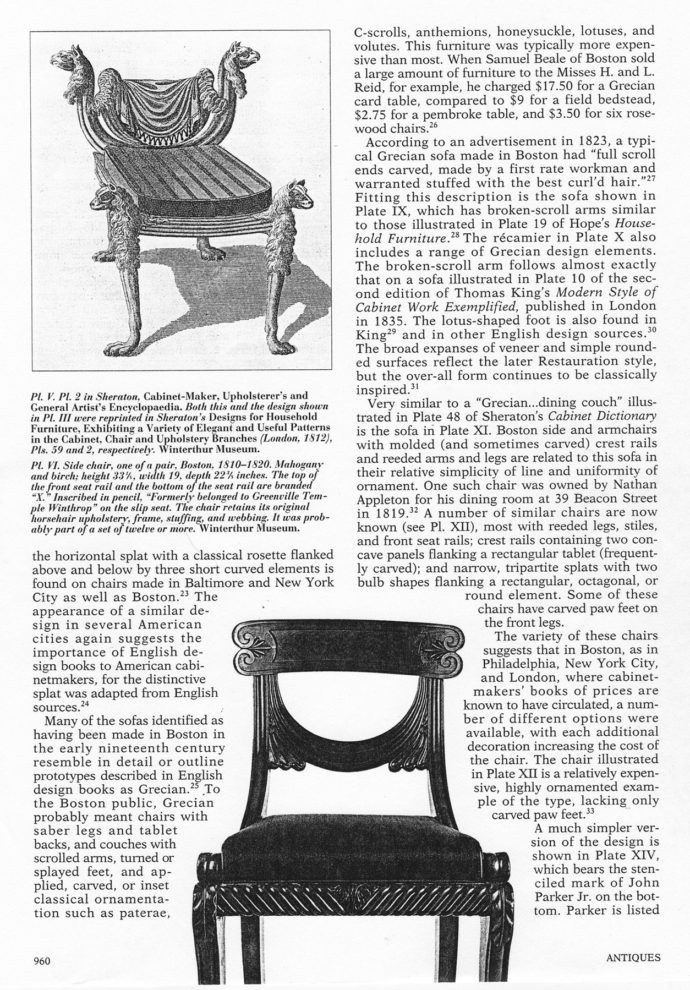

It doesn’t make any sense that, after I purchased the above set of six New York (Phyfe?) sidechairs in November 2019, I would be enamored with the idea of adding eight Boston sidechairs a year and a half later. I was just finishing up an interview for a print publication with Page Talbott, who is acknowledged as the doyen of Boston classical furniture studies, when I came upon a dealer’s website listing the eight chairs. These chairs were very similar to the chair at the bottom of a page (right) from her 1991 article in The Magazine Antiques entitled “Seating furniture in Boston 1810-1825.” I have kept a photocopy of her article tucked inside of the cover of Boston in the Age of Neo-Classicism, a book by Stuart P. Feld (1999, Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York). Talbott wrote the introduction for that book. I’ve always found that chair with a full faux drapery swag below the crest rail to be the epitome of elegant Boston classical cabinetmaking.

(To read about the purchase of the six New York sidechairs, please go to: http://www.scottponemone.com/red-chairs-how-they-got-that-way/)

Seeing those Boston chairs for sale got me very excited. So I asked the dealer for hi-res images of the chairs. And once they arrived, I scoured auction sites for similar chairs. And I leafed through books in my reference library as well. The pursuit was on.

In the meantime, the dealer with the eight chairs for sale also listed a piece of classical furniture rather unique to Baltimore: a marble-top table with a pull-out commode. So I did a similar search online and in books for that as well only to discover that I had inspected that table in person three years earlier and passed on it.

This ART I SEE post describes what I learned about both the chairs and the table and what I decided to do.

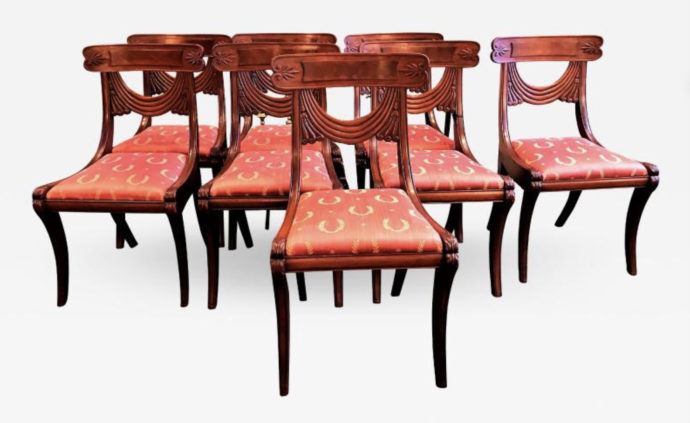

Listed as: “Circa 1825, Boston. This set of 8 classical chairs was the work of a highly skilled chairmaker in Boston in the first half of the 19th Century…. 19.5ʺW × 19ʺD × 35ʺH.”

THE CHAIRS

The only thing troubling about the listing for the eight chairs (above) was the price: $7,500. It seemed too low. Now I know prices for American federal (1800-1840) furniture have tanked in recent years, but it still seemed too low. Checking auction prices online I found a set of 12 chairs said to have descended from the Fales family in Boston that were sold at Skinner near Boston for over $80,000 in 2016. And a year earlier Skinner sold a set of six somewhat less elaborate but similar chairs for $12,500.

Fortunately the dealer with the eight chairs was only an hour away. It was certainly worth the drive. Entering the shop I spied the chairs and went to examine them. Almost immediately I sensed that something was wrong. I’m not saying that they were mislabeled as early 19th-century chairs. It’s that they just didn’t seem to be the product of an early 19th-century cabinetmaker to me. So I took a few photos, thanked the dealer and left without them.

My first sensation was that they appeared too tall. At 35 inches, they were taller than the 33 3/4 inches of the Fales chairs and taller than the 32 1/4 inches of the other set sold by Skinner. And chair illustrated in the Talbott article measured 33 1/8 inches tall. In the book Rather Elegant Than Showy: The Classical Furniture of Isaac Vose by Robert D. Mussey Jr. and Clark Pearse (2018, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston) are two similar chairs, one with a 33-inch height, the other at 32 7/8 inches. One of my early lessons as a collector was to learn that chairs reproduced in the Colonial Revival in the late 19th century through the first half of the 20th tended to be taller than period ones.

When I compared a Fales chair to the one of the eight for sale, I saw that the honeysuckle blossom tucked under the swag of the Fales chair was much better carved especially on the volutes at the bottom. But then it struck me of a far more important difference. The Fales chairs and all of the other chairs cited above with shorter heights had only three folds to the swag, while the chairs for sale had four.

The difference in the anthemeons at either end of the crest rail was not very significant. The five petals (or leaves) on the chairs for sale were one of the variations found on the shorter chairs. They can be seen on the chair in the Talbott article.

A further scan of auction records came up with the four armchairs that were auctioned in Florida in 2016. They were listed as: “Set of (4) 19th century mahogany Federal style saber leg chairs.” They had the four folds to the swags and had the same five petal (leaf) anthemeons on the crest rail as had the chairs I went to inspect. They sold for under $500 including buyers’ premium. Furthermore, they were even taller–36 inches-than the set I looked at. I asked Neely auctioneers why they used the word “style” to describe them but didn’t get a response.

To test my theory that the eight chairs for sale were made after 1850, I contacted Erica Lome, whose article “America by Design: Isaac Kaplan’s furniture for the Colonial Revival” in the 2017 edition of Chipstone Foundation’s annual publication American Furniture. Kaplan, who emigrated to Boston in 1904 from Eastern Europe, was the founder of the Kaplan Furniture Company. Lome wrote: “His reputation was of a highly skilled cabinetmaker known for his ability to imitate the style of early American furniture.” I was wondering if Lome was familiar with any contemporaries of Kaplan who could have produced the eight chairs for sale.

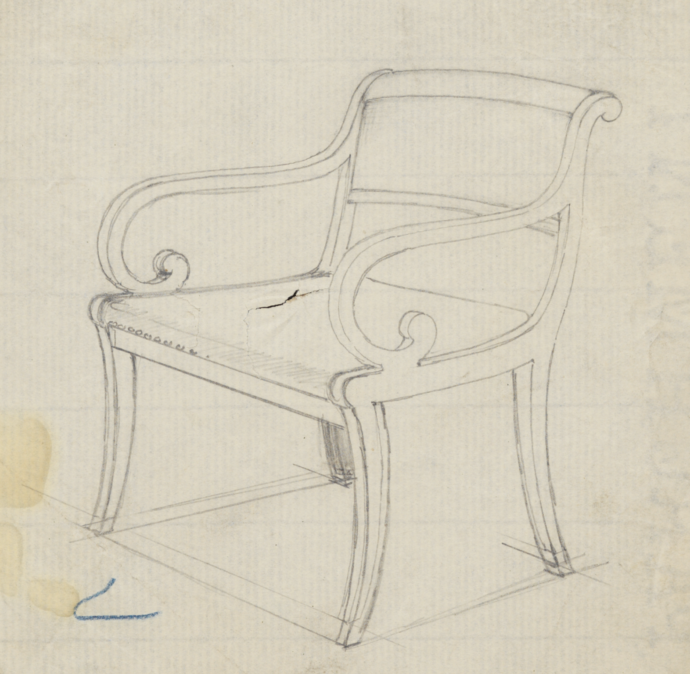

A pencil sketch of the classical revival chair from the archives of the A. H. Davenport company. (Photo courtesy of Historic New England)

Her initial response was: “It’s very possible the chairs you mentioned might have been made by A. H. Davenport, Irving & Casson, or Jordan Marsh & Co. The larger firms in Boston were making sophisticated classical revival furniture at that time, as were smaller, boutique firms.”

But after I sent her photos of the eight chairs, she said, “Unfortunately, I don’t have any information that could help you to make an attribution to any one maker or business in Boston. Without a mark or label, it’s all guesswork. Most manufacturers adapted Hepplewhite/Chippendale designs, so the chairs’ unique interpretation of the neoclassical splat might be one clue, but you would have to match it up with design drawings from all of these different businesses.”

Looking online for the three firms she mentioned, I came upon an Historic New England web page (LINK) that is a resource for A. H. Davenport and Irving & Casson. That page gave those firms’ dates as: “A. H. Davenport Co. (1880-1914), Irving and Casson (1884-1914), and their successor, Irving and Casson-A. H. Davenport Co. (1914-1973).” The Historic New England page also offered images of drawings from the A. H. Davenport firm. While chair pictured here doesn’t link the firm to the chairs I went to inspect, at least it shows that Davenport did make reproductions of classical furniture forms.

However, Jordan Marsh and Company was a Boston department store–in fact the nation’s first. It sold furniture but wasn’t a furniture maker itself.

Baltimore Commode

Before I traveled to see the eight chairs, I did an auction search on the Baltimore commode (washstand) that was listed on the same dealer’s website. Part of the description intrigued me. It said that the lid on the raised gallery behind the marble was replaced. The photo right is from a 2017 online auction listing by Alex Cooper auctions, just north of Baltimore. I went to that preview. In fact there were two very, very similar commodes. Besides the missing lid, this one had serious issues with the finish. The other commode had rebuilt drawers. So I passed on both. Each sold for just under $2,000 with buyer’s premium.

The commode as it appeared in the Alex Cooper online listing (right) and how it appeared on the dealer listing (left).

As you can see, the veneers on the drawer fronts match. So do the brass pulls. The King of Prussia marble is the same. The reeded stiles and reeded top edge of the gallery are the same. Even the single ring turnings atop the legs are the same. (The other commode sold at Alex Cooper had double ring turnings atop the legs.) It was obvious that the dealer had purchased the commode at Alex Cooper.

The dealer had painted inside of the commode pan white, but the green paint on the outside may be original.

Only one book in my reference library has a photo of a Baltimore washstand. It’s in Gregory Weidman’s and Jennifer Goldsborough’s 1993 book Classical Maryland 1815-1845 (Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore). The description under the photo (Fig. 168) in part reads: “In 1826 John Needles advertised a ‘bidet wash stand with marble top’ as part of a ‘large and elegant assortment’ of cabinet furniture. This example is one of many that have descended in Maryland Families, all of very similar form and decoration.”

The asking price was $4,500. Given the fact that the dealer had it for almost three years, I offered $3,500 and it was accepted. I thought that would give the dealer a bit of profit since the dealer had paid nearly $2,000 for it, had it refinished and had the soap compartment lid replaced. Had I tried to buy it at auction in 2017 and bid against the dealer, who knows what the hammer price would have been. In the long run I could well have been bidding against myself.

Of course its purchase would not have happened had I not gotten overly excited about owning Boston swag-back chairs.

You comments are most welcome. Please email me at: p1m1@comcast.net

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/second-chance-commode/trackback/