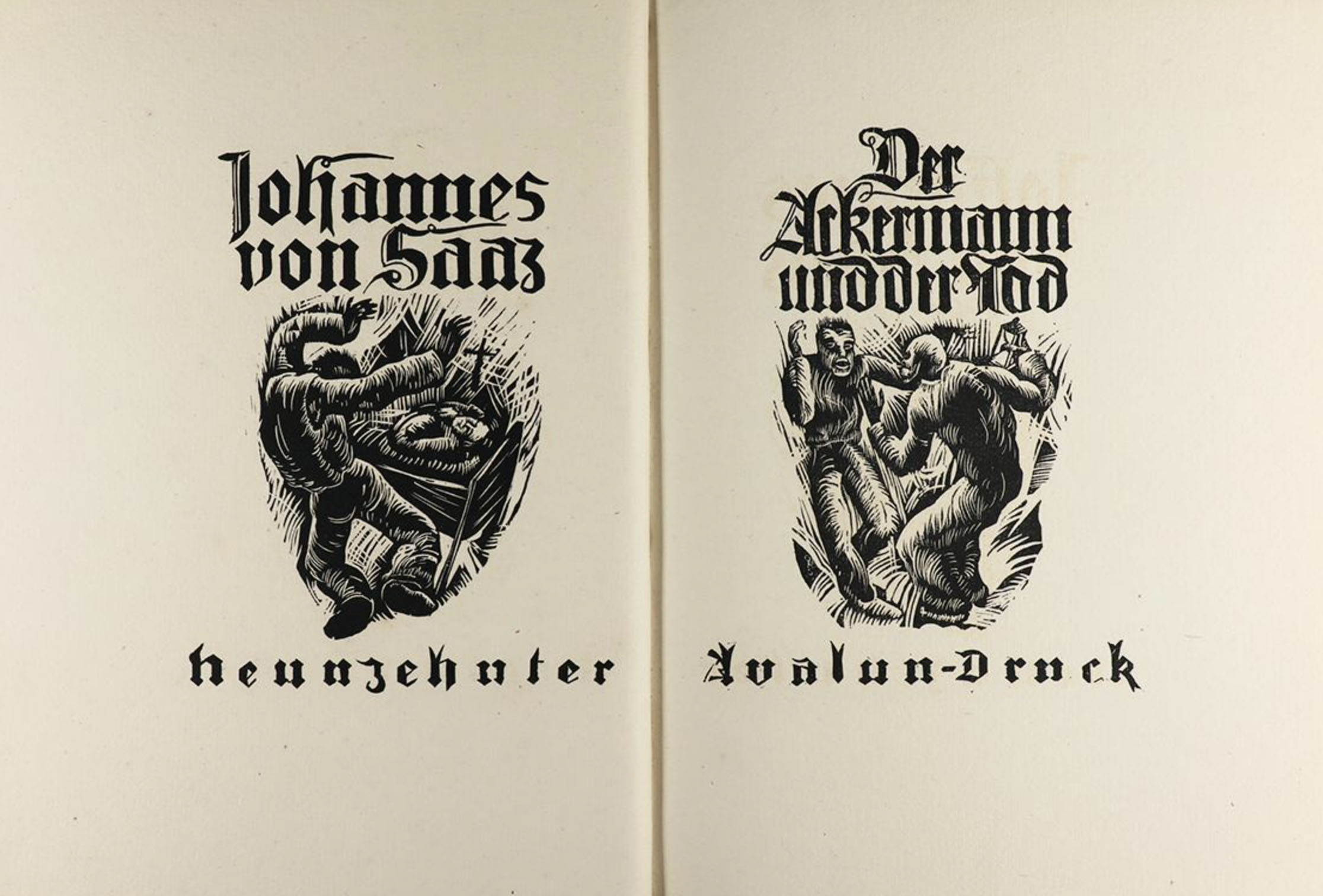

Schatz’s “Der Ackermann und der Tod” woodcuts

Introduction

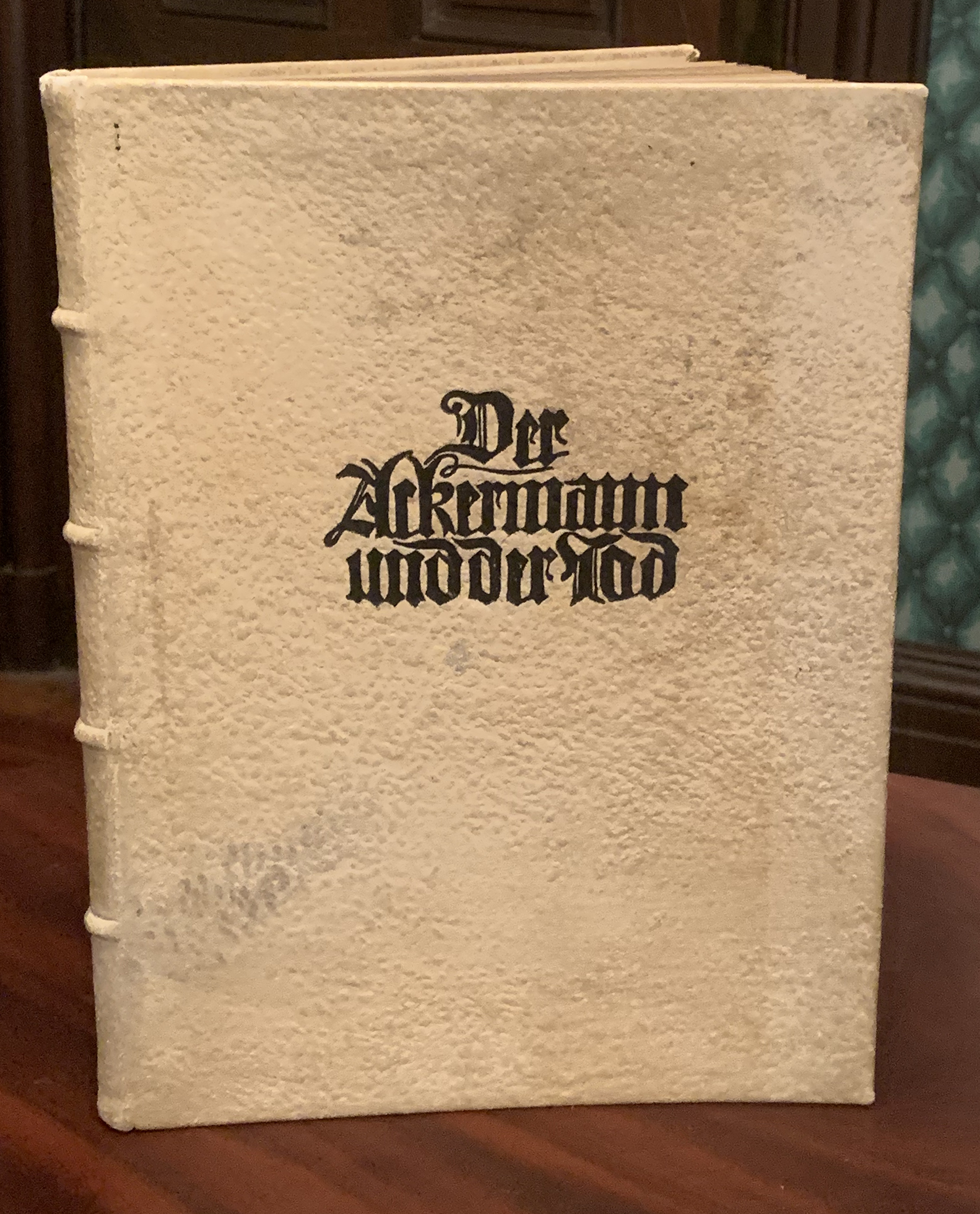

For a collector of prints done in series–whether compiled as a wordless narrative, as illustrations for a poem or novel, or as assembled in a portfolio–and often of prints with a personification of death, the 1922 edition of “Der Ackermann und Der Tod” with 12 woodcuts by Otto Rudolf Schatz was a compelling acquisition.

The text itself is fascinating because it originated in Bohemia within living memory of the Black Death (bubonic plague) that wiped out perhaps 50 percent of Europe’s population between 1346 to 1353. Its author Johannes von Tepl (also known as Johannes von Saaz) (1342/50-c.1414) was born during the plague years and wrote “Der Ackermann und Der Tod” around 1401. According to Wikipedia: “Not much is known about him; historians presume that he probably studied at universities in Prague, Bologna and Padua. In 1383, he became a solicitor in Zatec (Saaz) and in 1386 a rector of the town’s Latin school. He lived in Prague from 1411. He spent almost all of his life in the Kingdom of Bohemia, during the reign of kings Charles and Wenceslaus.”

Von Tepl is credited as the earliest writer of prose in early New High German. “Der Ackermann und Der Tod,” his best known work, is a humanist poem, that (according to Novelzilla YouTube transcript) “belongs to the genre of didactic literature, which aims to impart moral lessons or practical wisdom to its audience. The poem consists of a dialogue between Death (Tod) and a plowman (Ackermann), who engages in a philosophical and theological debate about the nature of life, death, and the afterlife. At its core, “Der Ackermann und der Tod” explores the universal theme of mortality and the human struggle to comprehend and accept the inevitability of death. The Ackermann (plowman) represents humanity, while Death serves as a grim reminder of life’s impermanence.

“The poem opens with the Ackermann lamenting the loss of his wife, prompting Death to appear and engage him in a dialogue. This encounter serves as the catalyst for a profound exploration of existential questions. Throughout the poem, Death assumes a didactic role, challenging the Ackermann’s beliefs and offering insights into the nature of existence. Death’s character is depicted as both menacing and wise, embodying the inescapable reality of mortality.”

Artist Otto Schatz made 11 woodcuts–plus the ones on the title pages (above)–to illustrate the von Tepl poem for Avalun Verlag (Vienna and Leipzig) in an edition of 125. In this ART I SEE post, I’ll attempt to match each of the woodcuts with the adjacent text (translated from the German). But before I do so, I’ll present a very few images of death in my collection to offer some perspective on how skeleton has been used over the past few centuries to represent Death. And I’ll also present a short biography on the artist.

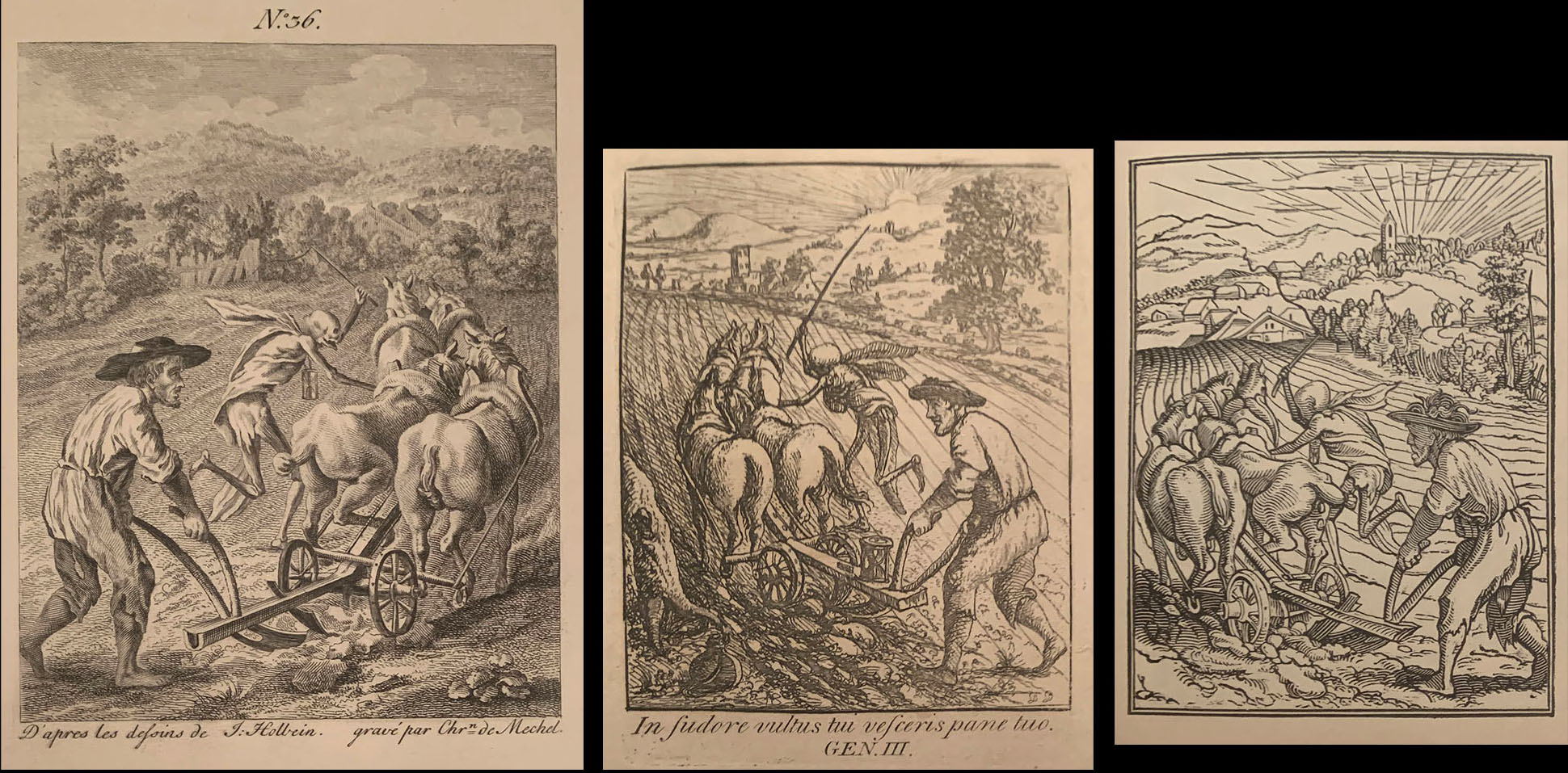

Skeletal Death

Above are three variations on the series of woodcuts by the German artist Hans Holbein (1497–1543), which he produced between 1523 and 1525. This series is described on the Public Domain website (LINK) with text by Ned Pennant-Rea: “In a series of action-packed scenes Death intrudes on the everyday lives of thirty-four people from various levels of society — from pope to physician to ploughman. Death gives each a special treatment: skewering a knight through the midriff with a lance; dragging a duchess by the feet out of her opulent bed; snapping a sailor’s mast in two. Death, the great leveller, lets no one escape.” In this sequence that evokes the sweep of the Black Death of some 75 years earlier, the plowman (“ploughman” in the British spelling or Ackermann in German) whose team of horses is being led astray by Death has his place pretty low down in the societal hierarchy.

The image on the right is the closest to Holbein’s conception. It appeared in “The Dance of Death” (William Pickering, London, 1833) with text by Francis Douce. The wood engravings is this volume, Douce writes, “have been executed with consummate skill and fidelity by Messrs. Bonner and Byfield…. They may justly be regarded as scarcely distinguishable from their fine originals.” The image measures 2 1/2″ x 1 7/8″ (6.5 x 4.8 cm).

The middle image is from “The Dance of Death” (W. Smith and Co., London, 1803) with 46 etchings by David Deuchar. His plowman (called a husbandman here) image adds an hourglass sitting on the plow. The text opposite this etching reads: “Were Death capable of considerations, what class of society would better deserve to be exempted from his ravages, than the laborers; incontestably the most useful, most laborious, and most productive of real opulence? But he is now striking the horses harnessed to this Husbandman’s plough….” This image measures 2 5/8″ x 2 1/8″ (6.7 x 5.4 cm).

The image on the left is from “Le Triumph de la Mort” (Verlag Konrad Wittner, Stuttgart, 1780) with delicate etchings by Christian von Mechel (1737-1817). The title page reads: “Gravé d’après les Dessins originaux de Jean Holbein” to claim that Mechel designed his plates from Holbein’s original drawings. But, according to the website dodedans.com (link), “von Mechel’s plates are not based on Holbein’s original drawings. On the other hand it was later (much later) discovered that they are copies of drawings made by the very young Peter Rubens.” This image measures 3 3/4″x 3″ (9/7 x 7.7 cm).

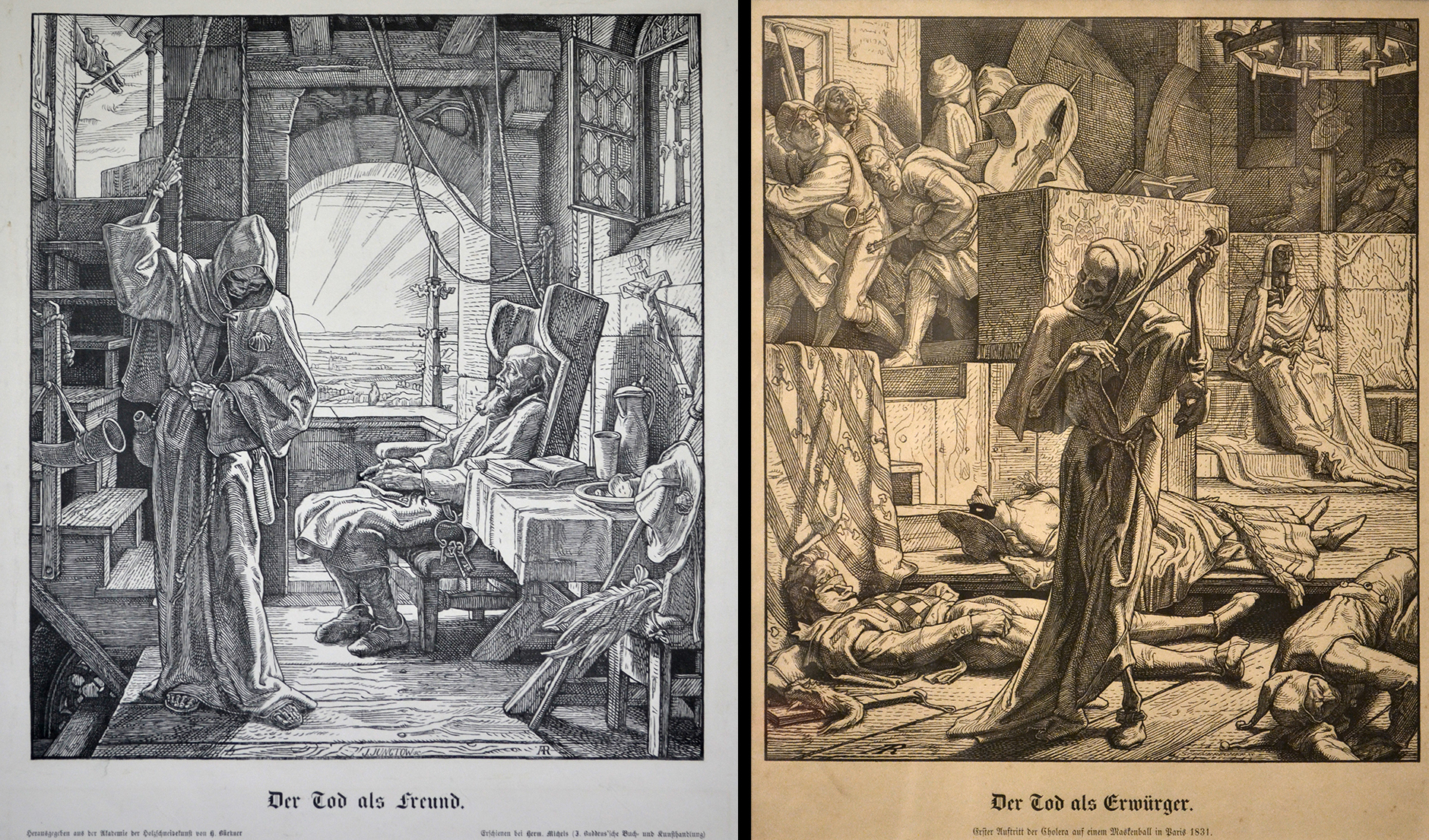

Often enough skeletal Death is partially clothed in part to make him less visible. In this well known pair of 1851 wood engravings based on drawings by the German artist Alfred Rethel (1816-1859), Death is shown to have opposite attributes. On the left, “Death as a Friend” in a hooded robe adorned with pilgrim’s clam shell insignia pulls on a bell tower rope to acknowledge the passing of the elderly man in a chair. Meanwhile on the right, “Death as an Enemy” with his bone violin breaks up a masked ball in Paris during a 1831 cholera outbreak. “Death as the Friend” measures 12″ x 10 3/4″ ( 30.5 x 27.3 cm); while “Death as an Enemy” is 12 1/4″ x 10 7/8″ (31.1 x 27.6 cm).

In the catalog for the exhibition “Art Medica: Art, Medicine and the Human Condition” (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1985), Diane Karp writes: “German wood engravings of the Renaissance period were one of the great loves of the painter Alfred Rethel. He sought to revive the medium in the mid-nineteenth century and looked for inspiration to the masters of the German tradition, particularly Hans Holbein the Younger.” Besides this pair, Holbein influenced Rethel to design a six-plate sequence on wood engravings “Ein Todtentanz aus dem Jahre 1848.” (To see an ART I SEE post on that sequence, please follow this link).

That Death is portrayed in both a comforting and a hostile mode in some ways reflects Johannes von Tepl’s Death as being both “wise and menacing.”

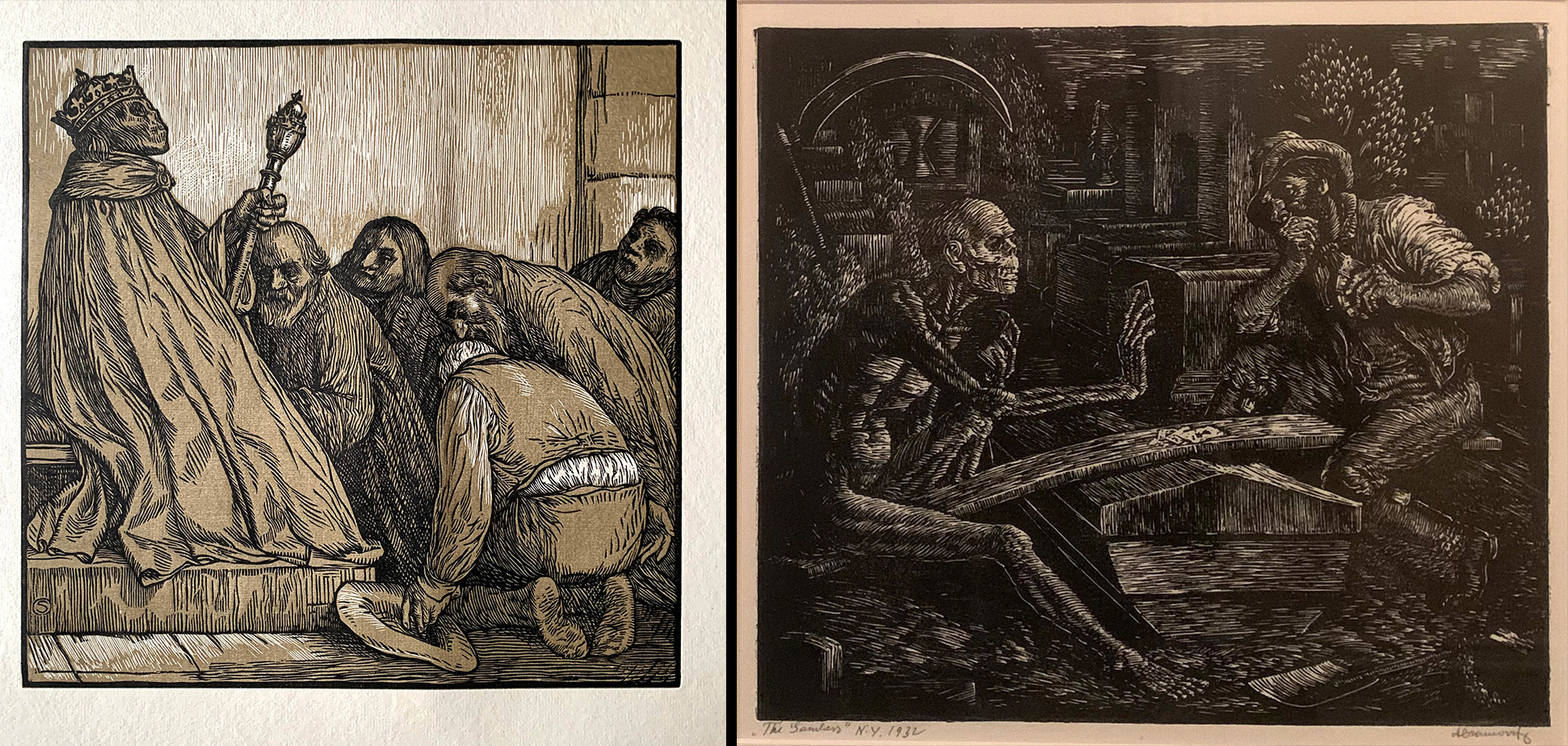

Here are two more images of Death from my collection. On the left is “Death the King” from William Strang’s “The Doings of Death,” a 1901 portfolio of chiaroscuro woodcuts published by Essex House Press. Strang (Scottish, 1859 – 1921) often turned to printmakers centuries earlier for his inspiration. In his Holbein tribute half of his 12 woodcuts present the traditional Death snatching away the living; in the other half, like this image, Death is shown as a part of society. This image measures 11 7/16″ x 11 7/16″. (29.1 x 29.1 cm).

Albert Abramovitz (Latvian-American, 1879 – 1963) featured Death in a number of the relief prints. In his 1932 wood engraving “The Gamblers” Death may be pretending to offer up a wager with a cemetery worker, but we know he has all the cards. Death is featured in a number of his prints in the traditional “take-no-prisoners” mode. The Brier Hill Gallery has a number of them posted online (link). This print measures 9 3/8” x 10 5/8” (24 x 27.1 cm).

Rudolf Otto Schatz

When you do an online search on Schatz where you click will tilt your impression of his oeuvre considerably. If you land on the honesterotica site (link), you will see only his licentious side in woodcuts and paintings again and again and again. If you land at the ottorudolfschatz.com website, you’ll see a number of paintings of nudes but none engaged in sex. Woodcuts will predominate. The ones dated from late 1910s to the early 1920s (when he made illustrations for “Der Ackermann und Der Tod”) will have rough, jagged cutting that you may expect from a German printmaker of that time. By mid 1920s his woodcuts have smoother cuts and more curves. And if you arrive at www.otto-rudolf-schatz.info you’ll only find a few paintings.

The honesterotic site, however, provides good biographical information on Schatz. Its biography relies on “the Vienna Dorotheum Museum’s Belvedere Research Centre’s comprehensive 2018 monograph of Otto Rudolf Schatz.” It reads:

“The Austrian painter, graphic designer and book illustrator Otto Rudolf Schatz is often regarded as one of the most significant artists of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement of the 1920s and 30s, though such a characterisation easily oversimplifies both the movement and Schatz’s relationship with it. ‘Neue Sachlichkeit’ is usually translated as ‘New Objectivity’, but as the art historian Dennis Crockett points out, there is no direct English translation – ‘Sache’ means a thing, fact, or object, and ‘sachlich’ factual, matter-of-fact, practical, precise. Thus a closer translation of Neue Sachlichkeit might be ‘a new matter-of-factness’, and that certainly describes Schatz and his work.

“Schatz was born into a middle-class civil servant’s family, and after leaving school received excellent training at the Vienna School of Applied Arts. His eight months of military service left him disillusioned, and he remained a committed pacifist all his life. In 1919 he tried his hand at a number of different jobs, before feeling ready in 1920 to embark on a career as an independent artist. He was an excellent draftsman and quickly mastered a wide range of graphic techniques, including watercolour, tempera, oil painting, woodcut and lithography, adeptly employing each medium according to his chosen subject. ….

“Schatz was well informed about contemporary artistic developments, but having initially been an admirer of Egon Schiele he showed little interest in stylistic movements or luminaries of the art world, instead choosing to work in whichever manner best expressed his personal outlook on life, sometimes in different styles simultaneously. He was also quite clear about the distinction between works he made to earn money and those he created for the sake of art. To make a living and put food on the table he painted tavern scenes and landscapes. Whenever he was in severe financial straits, he also created erotic pictures in substantial numbers, which were guaranteed to sell. This does not mean that his erotic work was always produced hurriedly; he was something of a perfectionist, and depending on his mood and the respective client his erotic output ranged from the edge of the pornographic to depictions of a powerful, unbounded eroticism.

“In 1934 Schatz met Valerie ‘Vally’ Wittal, the daughter of a wealthy Jewish shop-owner from Brno in Moravia, now part of the Czech Republic, and after a short and passionate romance they were married in December of that year. For Otto the new-found affluence provided the resources to travel and become more involved in the international art scene, and from 1935 to 1937 the couple travelled extensively throughout Europe and to the USA. His large canvases of Venice, southern France and New York attracted much attention, and today fetch a high price. Because of Schatz’s outspoken anti-fascist sentiments and his wife’s Jewish origins, the couple fled Vienna when German troops entered Austria in March 1938, going first to Brno and then to Italy. When Nazi racial laws also came into effect in Italy, they returned to Brno and eventually settled in Prague. In October 1944 Schatz was betrayed to the Gestapo, interned for sixteen days, and in November 1944 deported to a labour camp in Klettendorf near Breslau. Vally, meanwhile, was interned in the Theresienstadt concentration camp.

“After the Russians liberated Auschwitz-Birkenau, Schatz was moved via Gräditz concentration camp to Bistritz bei Beneschau, where he remained until the end of the war in early May 1945, having been critically ill for the final six weeks of his internment. Back in Prague he was reunited with Vally, who had also survived her internment. The marriage was not to last, however; Vally was well aware of her husband’s erratic lifestyle and his relationships with several other women, and filed for divorce, shortly afterwards emigrating to the USA. Schatz returned to Vienna in November 1945, taking what was left of his possessions and pictures. … A lifelong smoker, he died of lung cancer in April 1961.”

More details on Schatz’s publishing and exhibition history are on the otto-rudolf-schatz website (link).

Der Ackermann und der Tod

This 1922 Avalun Verlag edition of “Der Ackermann und der Tod” was leather bound and printed in 125 copies, this being No. 67. The book measures 11 1/2″ x 8 1/2″ (29.4 x 22 cm).

Needless to say, the text of the book is in German, in a beautiful letterpress Gothic font. For a translation I’ve turned to Michael Haldane and his “Dr. Michael Haldane’s Translation Page” (link). Most but not all of his translations are from German to English. (I’ve kept his British spellings of English words.) In his precede to Johannes von Tepl’s work he writes:

“Der Ackermann und der Tod (‘The Ploughman and Death’ or ‘The Husbandman and Death’ – both titles have much to commend them), also known as Der Ackermann aus Böhmen (‘The Bohemian Ploughman’), was composed around 1401 by Johannes von Tepl (1342/50-c.1414), a public official in Saaz in Bohemia. It may represent his reaction to the death of his wife Margaretha, who died giving birth on August 1, 1400; the fact that Tepl employed a highly rhetorical style, displaying his learning through numerous allusions and the frequent use of legal phraseology, does not necessarily make his work ‘artificial’ or a purely artistic construct. He may be utilising the rhetorical tropes he learnt at school and the popular genre of the altercatio (‘The Owl and the Nightingale’ etc.) to channel his grief and control his reaction to a shattering personal experience. The work is a learned and lively dialogue with a rhythm that calls for it to be read out loud, and it provides an excellent treatment of a theme that can be found in literature from Gilgamesh to the present, and which will always haunt the thoughts of mankind: the human confrontation with death.

“Although this text has excited a substantial amount of critical comment, especially with regard to its relation to the mediaeval tradition and Renaissance humanism, it has seldom been translated into English. Tepl’s language is that of the Saxon Chancery in Prague, the south-eastern German dialect on which Luther partly based the language of his Bible. The edition used for my translation is the parallel-text version with a translation into modern German by Felix Genzmer. I followed the original, its rhetorical intent, and its rhythm, as much as possible; and I did not shirk the subjunctive.”

For this ART I SEE post, I present about 60 percent of the text as translated by Haldane, enough I hope to convey the tenor of the dialog between the Plowman and Death. Where I have comments on Otto Rudolf Schatz’s woodcuts, I’ll post them in blue.

Chapter 1 Husbandman

Ferocious effacer of every being, terrible outlaw of all creation, hideous butcher of every human, Death, you take my curse! … Ferocious effacer of every being, terrible outlaw of all creation, hideous butcher of every human, Death, you take my curse!

Ch 2 Death

We are challenged by appalling and incredible complaints. Whence they have come is, in truth, unknown to Us. But threats, curses, screams of hue and cry, hand-wringing, and every kind of attack have never yet done Us any harm ….

But name yourself, and do not withhold those matters in which We have met you with such dreadful violence. We wish to be right and just before you; right and just are Our proceedings. We do not know what crime you are, so wantonly, laying to Our name.

Ch 3 Husbandman

I am a Husbandman by name…. and I live in the land of Bohemia. I will always be spiteful, inimical, adversarial to you: for horribly you have torn my 12th letter [referring to his wife Margaretha], my hoard of joys, out of my alphabet; deplorably you have weeded the bright summer flower of my delights from the meadow of my heart; maliciously you have sundered me from the prop of my happiness, my chosen turtle-dove: you have committed irretrievable robbery on me!

Ch 4 Death

We performed our act of grace on a respectable, blessed young lady there; her letter was the twelfth. She was virtuous and free from blemish; for We were present at her birth. … At that time, Lady Honour sent her a gusseted mantle and garland, in the hands of Lady Fortune. She took the mantle and garland with her, whole, untorn, and untarnished, to the grave… Perhaps this is the one you mean; We know of no other.

Ch 5 Husbandman

Yes, sir, I was her loving spouse, and she my sweetheart. You took her away, the joy-filled feast for my eyes: she is gone, my peaceful shield from hardship; my soothsaying, divining rod is away. She is gone, gone! …. Dole without ending, woe without respite, miserable sinking, felled plunging, eternal fall be given to you, Death, to you and yours! Die besmirched with vice, greedy with disgrace and gnashing your teeth, and perish in the stink of Hell! God deprive you of your power and reduce you to dust!

Ch 6 Death

We will prove that We weigh justly, judge justly, and act justly in the world: We spare none for the title, take no heed of great knowledge, pay no regard to any form of beauty, and do not blink at the sight of talent, love, sorrow, age, youth or other qualities. We do as the sun, who shines over good and evil: We take good and evil into Our power.

Ch 7 Husbandman

Could I curse, could I rail, could I revile you to cause you the worst of evils, then that would be no more than you have despicably deserved of me. For bitter plaints must follow bitter grief: it would be inhuman of me not to weep for so virtuous a gift from God, which none but God alone can give. … Truly, were there any good in you, you yourself would feel pity. I will turn away from you, speak no good of you, I will oppose you for ever with all my power: all God’s Creation shall assist me in my strivings against you; all that is in Heaven, on Earth and in Hell, hate you and feud with you!

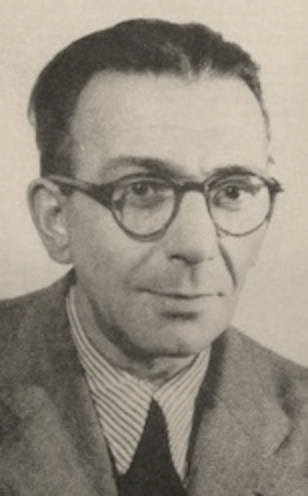

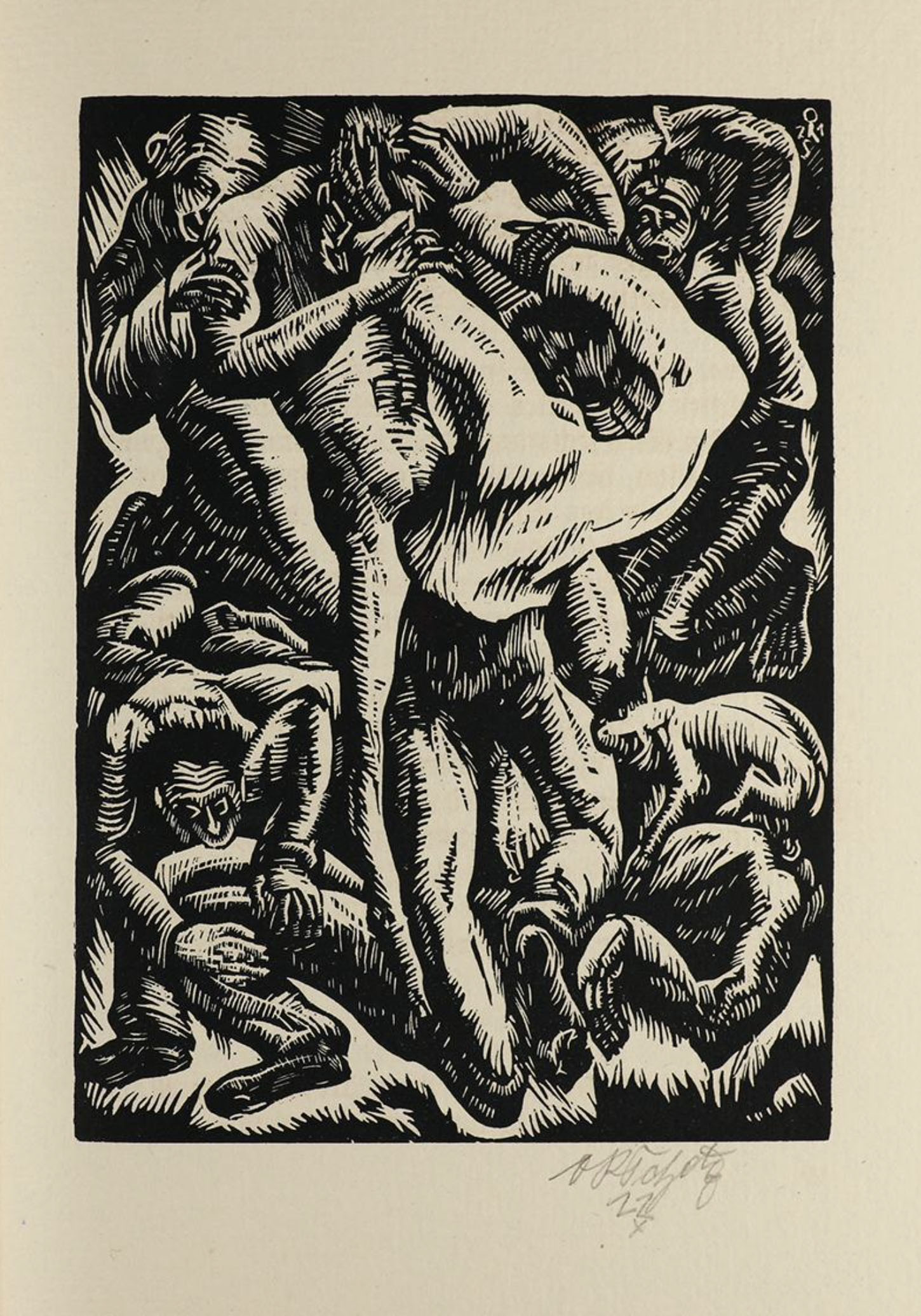

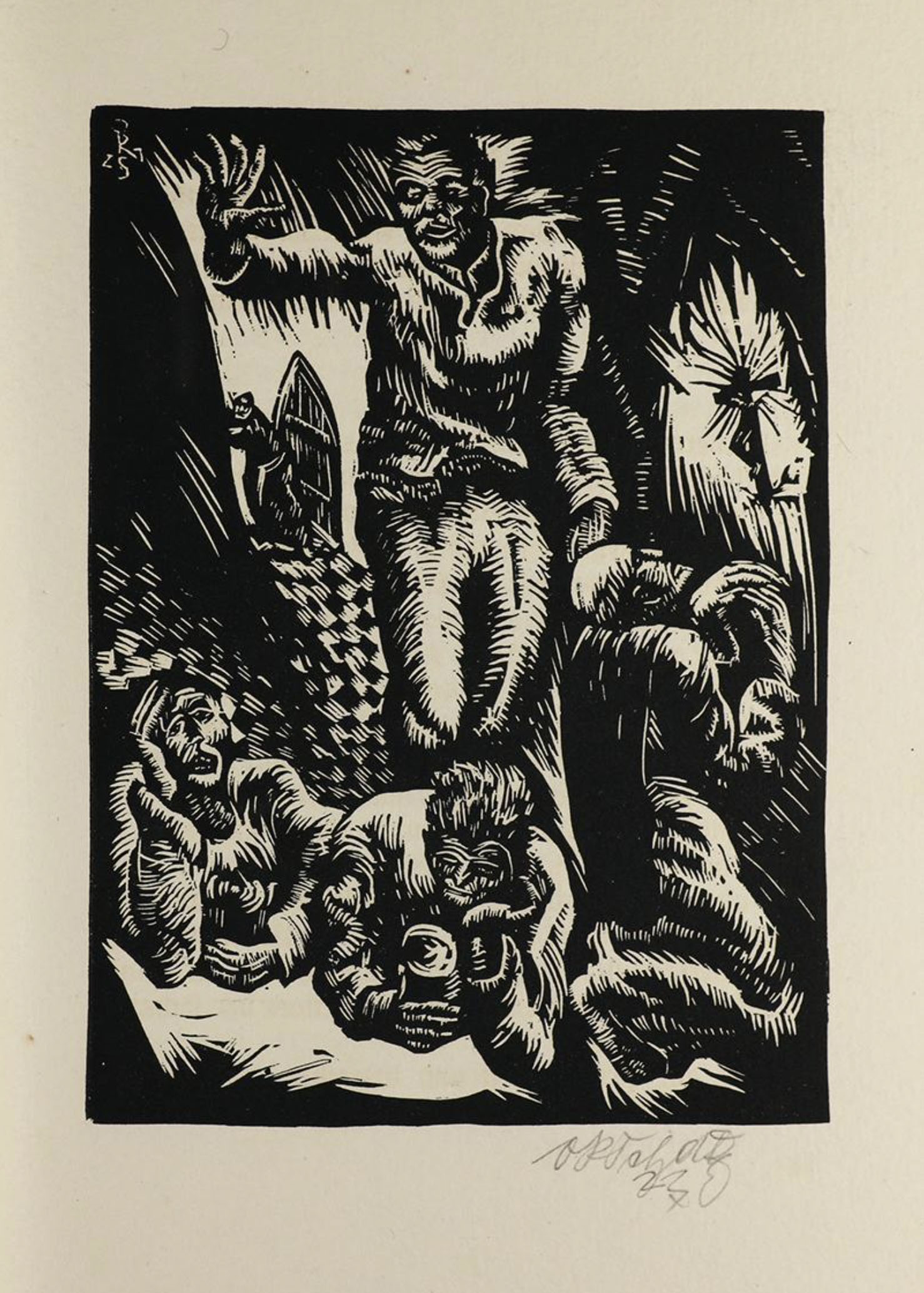

In this woodcut cowering humans crush together opposite Death with his hourglass and small scythe. Humans react this way despite Death’s words: “We will prove that We weigh justly, judge justly, and act justly in the world.”

Ch 8 Death

God has given Heaven’s Throne to the good spirits, the Abyss of Hell to the evil, and the terrestrial lands to Our portion. In Heaven, peace and reward for virtue; in Hell, torment and punishment for sin; this sphere of Earth with its flowing rivers and all they contain was commended Us by the mighty Duke of all Worlds, with the order that We uproot and weed out all superfluity. If you imagine, foolish man, if you consider, and chisel into your reason with a burin, then you will find: if We had not eradicated, since the time when the first man was worked from clay, the growth and increase of humans on Earth, of beasts and worms in the barren wastes and wild woods, of scale-bearing, slippery fishes in the waters – then no one would now exist for gnats, no one would venture out for wolves, each man would guzzle another, each beast another, each living creature another, for they would lack food, and the Earth would be too narrow for them. He is foolish who weeps for mortals. Desist! The living to the living, the dead to the dead, as hitherto. Consider your cause more deeply, you fool, before you begin to complain!

Ch 9 Husbandman

I have irretrievably lost my highest treasure – should I not mourn? … Let others say what they will: when God gifts a man a pure, chaste and beautiful wife, this is a real gift, one that is higher than every earthly, material gift. … What does the fool know of this, who has never drunk from this fountain of youth? And crushing heartache may have befallen me, yet I thank God sincerely, for that I have known the flawless lady. You, evil Death, enemy of all mankind, be eternally hateful to God!

Ch 10 Death

You have not drunk from the fountain of wisdom; I mark that from your words. You have not seen the working of nature; you have not peered into the mixture of worldly events; you have not beheld the transformation of flesh: you are an ignorant whelp. … [naming plants, animals, and peoples] how all earthly creatures, however intelligent, and charming, and strong they may be, however long they preserve themselves, however long they continue – one and all must come to nought. … You yourself will not escape Us, although this may be far from your thoughts at present. “Everyone to follow!” each one of you must say. Your plaint is invalid; it helps you nought; it proceeds from a torpid mind.

Ch 11 Husbandman

I have every faith in God, who has power over me and you, that He will shield me from you, and take severe revenge on you for the aforesaid outrage you have done me. You declaim like a trickster; you mix truth with falsehoods, intending to beat my enormous soul-sorrow, my mind-grief and heartache, out of sight, out of mind, out of senses. … Oh, oh, oh! brazen murderer, Master Death, vicious brat! the torturer be your judge and tie you with the words “Forgive me!” to the rack!*

* In many places it was the custom for the torturer to ask forgiveness of the tortured (Genzmer, 1984).

Here the Plowman imagines that by entreating God to protect him from Death that God would raise a hand against Death, who would walk away.

Ch 12 Death

Could you measure, weigh, count and judge correctly, you would not discharge such words from a hollow head. You curse and demand vengeance without understanding and without need. What use is such asininity? We have already said: all that is rich in thought, noble, honourable, upright, and everything living, must perish by Our hand. …

But I shall tell you something else: the more love that fell your way, the more sorrow will befall you; if you had abstained from love, you would now be relieved of sorrow; the greater the love you enjoy, the greater the sorrow of life without love. Wife, child, wealth and all earthly goods must bring some measure of joy at first, and a greater of sorrow at last; all earthly love must turn to sorrow; sorrow is love’s end, the end of joy is grief, sadness must follow pleasure, the enjoyment of one’s will must end in disaffection – to such an end all living things must run. Learn a little more, if you wish to cackle with wisdom!

Ch 13 Husbandman

After injury comes insult; those in distress feel this all too well. And in this wise am I, an injured man, served by you. You have unbedded me from love and wedded me to sorrow; so long as God wills, must I suffer this at your hands. However dull-witted I may be, however little wisdom I may have acquired from sagacious masters, I am still well aware that you are the robber of my honour, the thief of my joys, the stealer of my good days, the devastator of my delights, and the destroyer of all that procured and guaranteed me a blissful life. … Miserable, alone, overwhelmed by grief, I remain without your compensation; you have not yet been able to make me amends for your great misdemeanour. … Prince of the Heavenly Host, make good to me my tremendous loss, my great afflication, my wretched sorrow and pitiful call to arms! So avenge me on the arch-rogue, on Death, God, avenger of atrocity!

Ch 14 Death

… You complain that We have caused your sorrow through your so very dear wife. Yet she has been served with kindness and mercy: We have taken her into Our grace in joyful youth, with a proud body, in the best days of her life, with the highest esteem, at the best time, with honour inviolate. …

However spiteful you may be towards Us, We shall wish without grudges that your soul abide with hers in the celestial dwelling up there, and your body with hers in the terrestrial vault down here. We would stand surety to you that you will enjoy her beneficence. Be silent, cease! As little as you can deprive the sun of its light, the moon of its coldness, fire of its heat, and water of its wetness, so little can you rob Us of Our power.

Ch 15 Husbandman

A guilty man needs to colour his words. As you are doing. It is your custom to show yourself sweet and sour, gentle and harsh, kind and severe, to those you intend to deceive: so much is clear from my experience. …

The malefactor is you. And so I would like to know who you are, what you are, where you are, whence you are, and what good you do, for you to possess so much power and to have challenged me so evilly without warning, desolated my bliss-covered meadow, undermined and brought down my tower of strength.

Send, Lord, plagues; undertake retaliation; shackle and eradicate abominable Death, Your enemy, and enemy to all! Truly, Lord, there is nothing in Your creation more heinous, nothing more hideous, nothing more cruel, nothing more unjust, than Death!

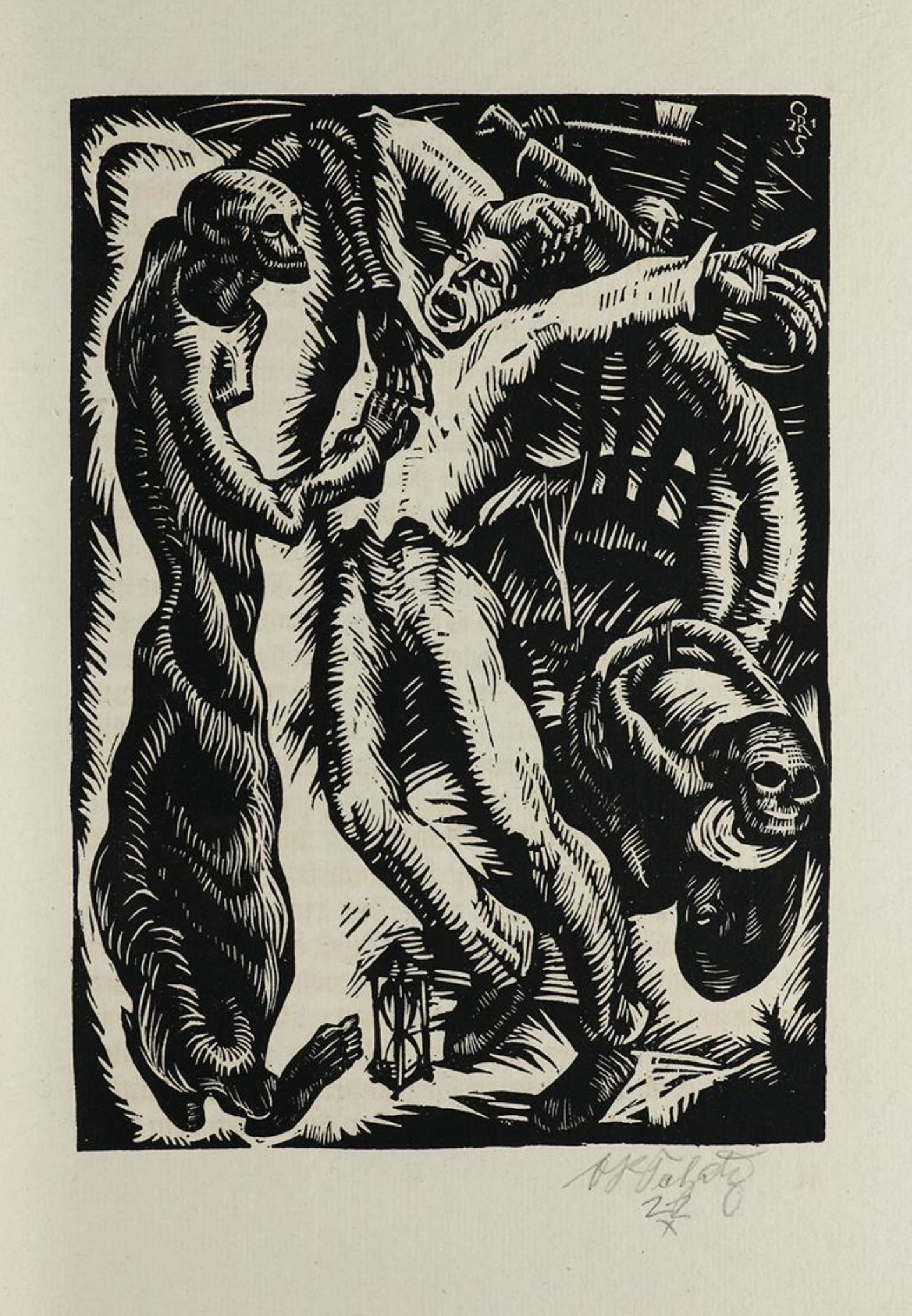

It’s hard to tell who’s fighting whom. The standing figure with his back to the viewer is being bitten on the leg by a dog. The head of his opponent is covered. In the lower left a person is biting the leg of another person. Perhaps this is to show the general stupidity of man, for Death then says: “Senseless people name evil good, call good evil.”

Ch 16 Death

Senseless people name evil good, call good evil. As you are doing. You accuse Us of passing false judgement: you do Us injustice. We shall prove this to you. You ask who We are: We are God’s handle, Master Death, a truly effective reaper. ….

You ask what We are: We are nothing, and yet something. Nothing, because We have neither life, nor being, nor form, and We are no spirit, not visible, not tangible; something, because We are the end of life, the end of existence, the beginning of nullity, a cross between the two. …

You ask where We are: We are from the Earthly Paradise. God created Us there and gave Us Our true name ….

You ask what good We do: you have already heard that We bring the world more advantage than harm. Now cease, rest content, and thank Us for the kindness we have done you!

Ch 17 Husbandman

Although you fell into the worldly paradise as a reaper who strives after justice, your scythe hews unevenly: it uproots the flowers with violence, and leaves thistles standing; the weeds remain, the good herbs must perish. … Where have they gone, they who lived on Earth and talked with God, who won grace and favour and mercy from His hands? Where have they gone, they who had their seat on Earth, who walked beneath the stars and determined the planets? …. Who bears the guilt for that? If you dared admit the truth, Master Death, you would name yourself.

Ch 18 Death

Who understands nothing of the matter, he can say nothing of the matter. And this has happened to Us. We did not know that you were so splendid a man. ….

[Death mocks the Plowman by pretending the Plowman performed so many wonderful deals over the millennia.]

If We had realised who you were, We would have done as you command; We would have allowed your wife and all mankind to live for ever. And We would have done this to honour you alone: for you are, in truth, an intelligent ass!

Ch 19 Husbandman

Men must often endure mockery and ill-treatment for the sake of the truth. And this is happening to me. ….

Either you redress the malicious wrong you have committed against my sorrow-averter, against me and my children, or you come with me to God, who is the righteous judge of me, and you, and all the world. You may well request that I leave the matter in your hands; I trusted you to see your unjustness for yourself and afterwards give me satisfaction for your grievous undeed. Follow your reason! Otherwise the hammer must strike the anvil, force against force, come what may!

To the right of the main figures, Death has his hands bound behind him and his head rests on the stump of wood. Behind him is a human with an axe raised above his head, about to behead Death. Is this the vengeance that the Plowman believes Death deserves?

Ch 20 Death

People are pacified by good words, reason holds people to moderation, patience brings people to honour, and an angry man cannot decide what is truth. Had you spoken amicably to Us earlier, We would have amicably instructed you that you may not, in all propriety, lament and weep for the death of your wife. …. as soon as a human is born, so soon does he drink to clinch the deal of death. The end is brother to the beginning….

If you weep for your wife’s youth, you are wrong to do so; as soon as a human has life, so soon is he old enough to die. …

If you lament her beauty, then that is childish of you: every single human’s beauty must be destroyed by either age or death. … Let go! Do not lament a loss you cannot retrieve.

Ch 21 Husbandman

… Now, if a good punisher is supposed to be a good instructor, then advise me, teach me how I am to excavate, eradicate and expel such unspeakable sorrow, such deplorable grief, such sadness beyond measure from my heart, from my mind and from my senses. …

You owe me help, advice, and compensation; you did me the harm. If this does not happen, then even if God in His omnipotence had no vengeance, it would still have to be avenged, should shovel and hoe be exerted once more.

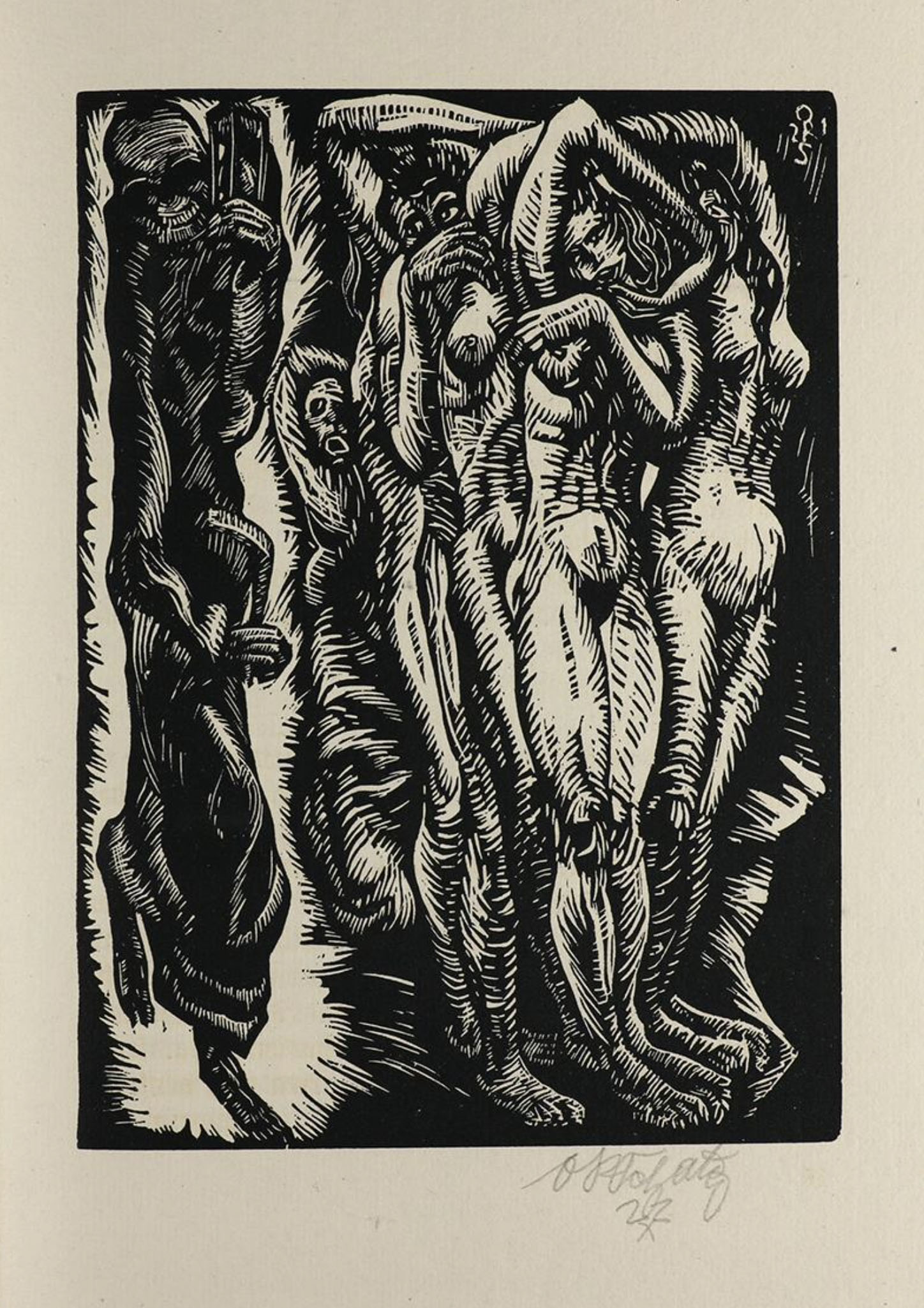

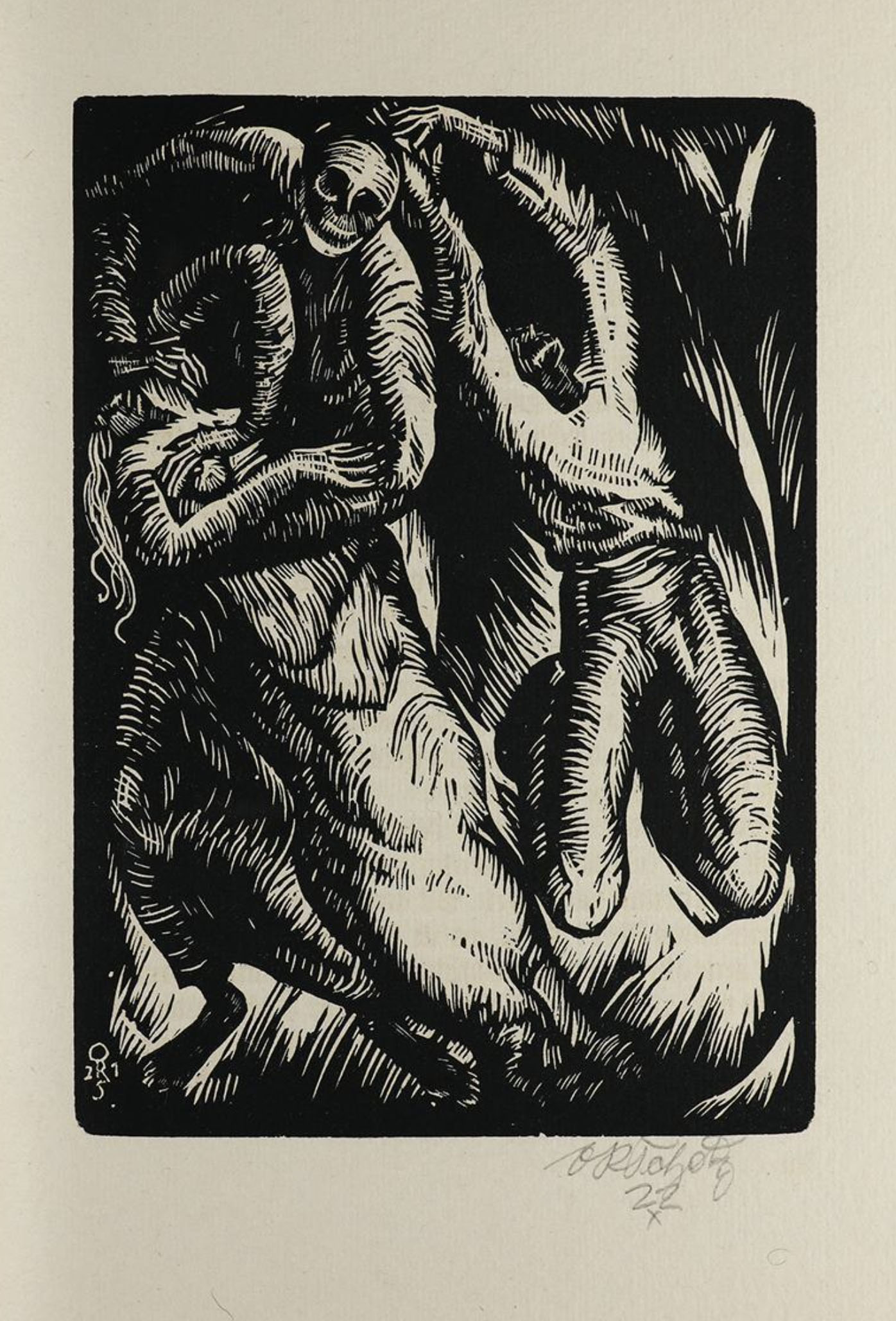

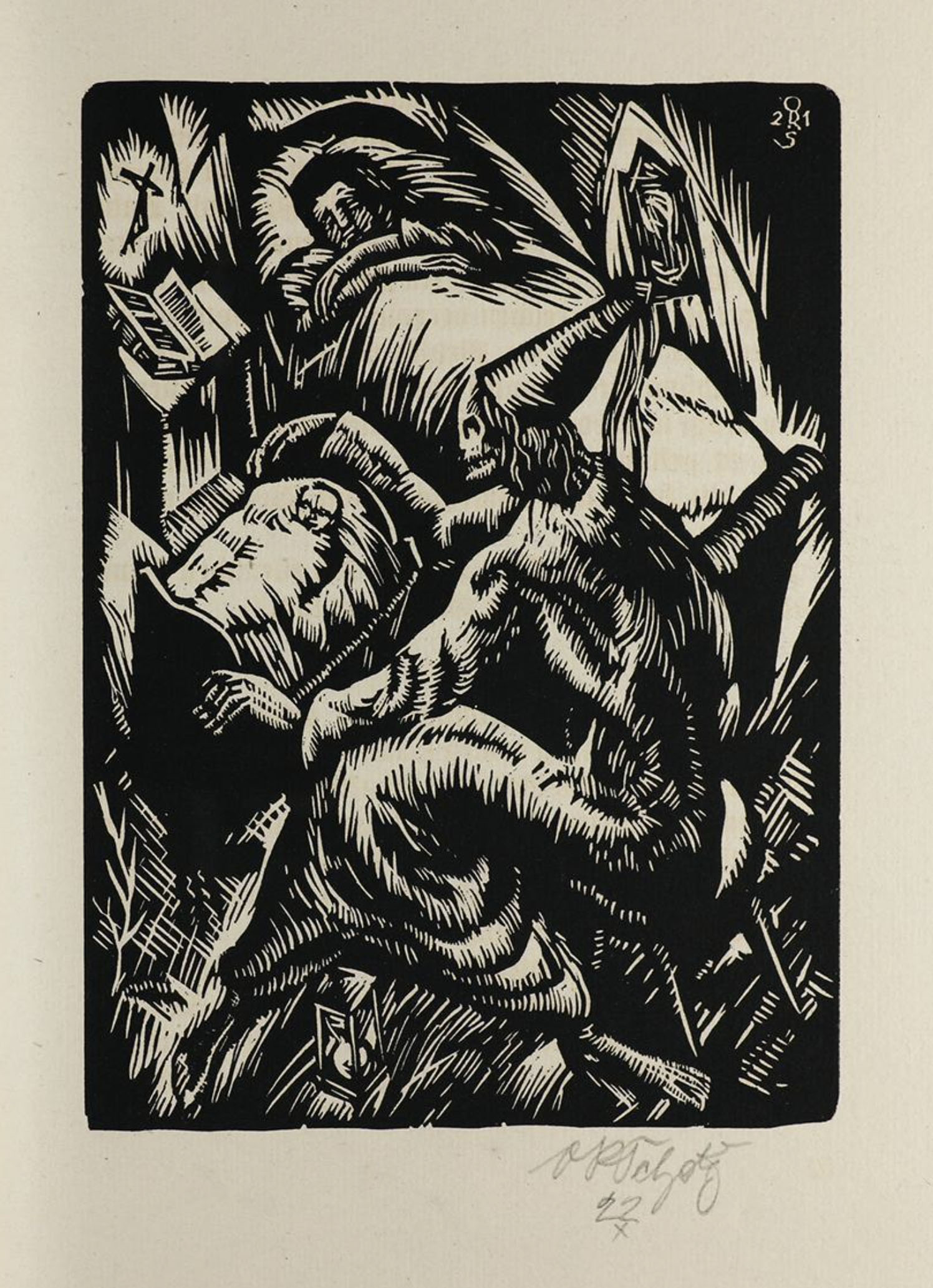

This woodcut is to make manifest the Plowman’s “unspeakable sorrow” upon the death of is wife.

Ch 22 Death

…. We have already explained to you that Death shall be beyond the impeachment of mortals. The reason being that We are a tax-collector, to whom humankind must declare and pay the toll of their lives. So why do you resist? Truly: he who will deceive Us deceives himself.

You ask for advice on how to put the grief from your heart. … Joy and fear shorten, hope and sorrow lengthen, the duration of time. Whoever does not banish these four from his mind must live with anxiety at all times. After joy sorrow, after love grief: such is the way of this Earth. Joy and grief must always be bound together. The end of one is where the other begins. … Drive the remembrance of love from your heart, from your senses, from your mind, and at once you will be relieved from sorrow! …

If you will not do this, then further grief awaits you. … I have counselled you enough. Can you understand, blunt-wit?

Ch 23 Husbandman

Time brings man to an awareness of this truth: the more learned, the more able. Your pronouncements are sweet and lively, as I am now beginning to perceive. But if joy, love, delight and diversion should be banished from the world, then the world would be in a bad way. … If good thoughts were taken from the mind, evil ones would enter. Good out, evil in; evil out, good in; and this exchange must endure until the end of the world. …

Now, if I were to beat the memory of my dearly beloved from my mind, an evil memory would return to my head: all the more reason for keeping my dearly beloved in constant remembrance. When great, heartfelt love is transformed into great, heartfelt sorrow, who can forget this so soon? That is what evil people do. …. Sir Death, you must advise more truly, if your counsel is to bring benefit; or else you must, Sir Bat, even more than the sparrowhawk, bear the enmity of birds!

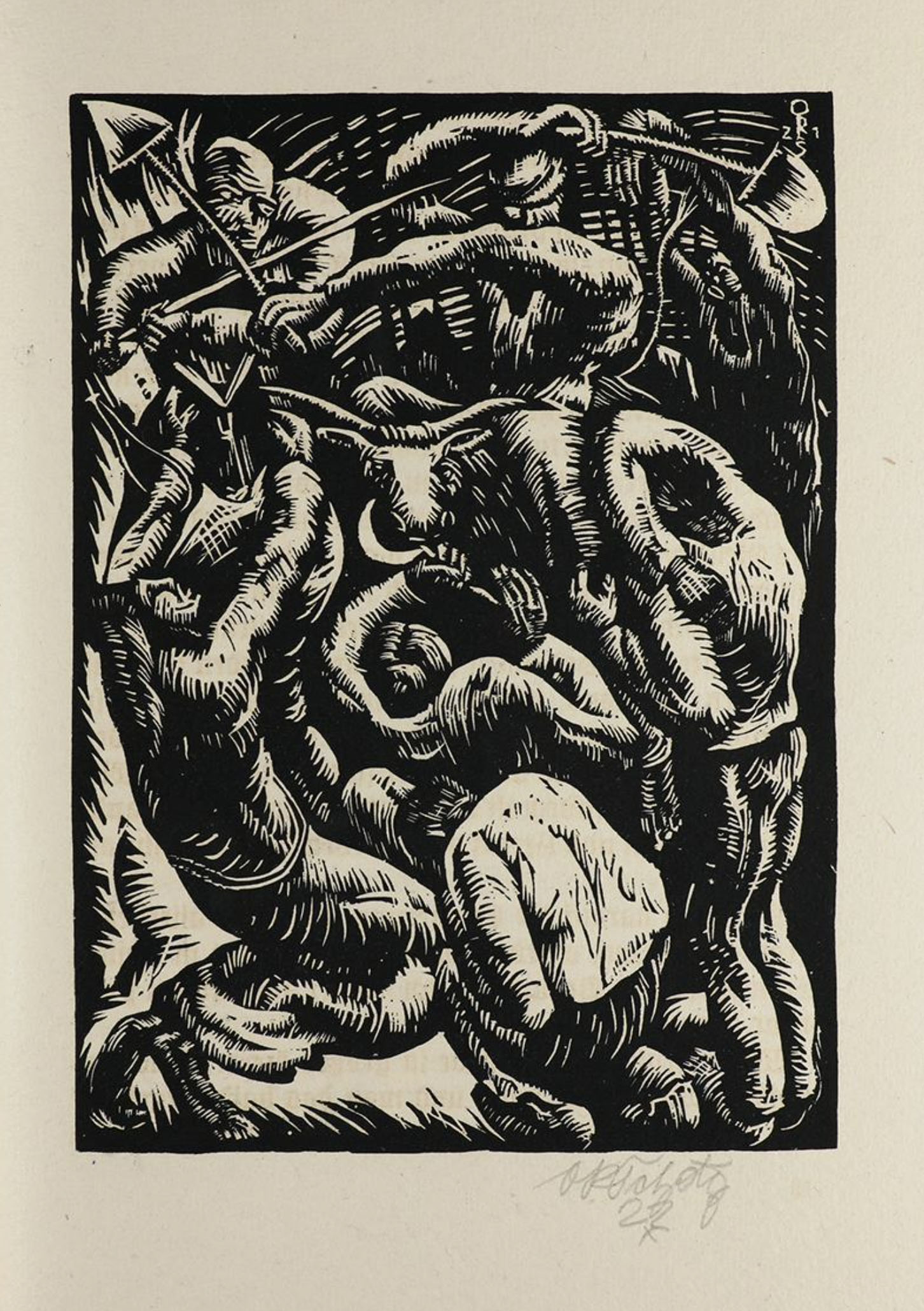

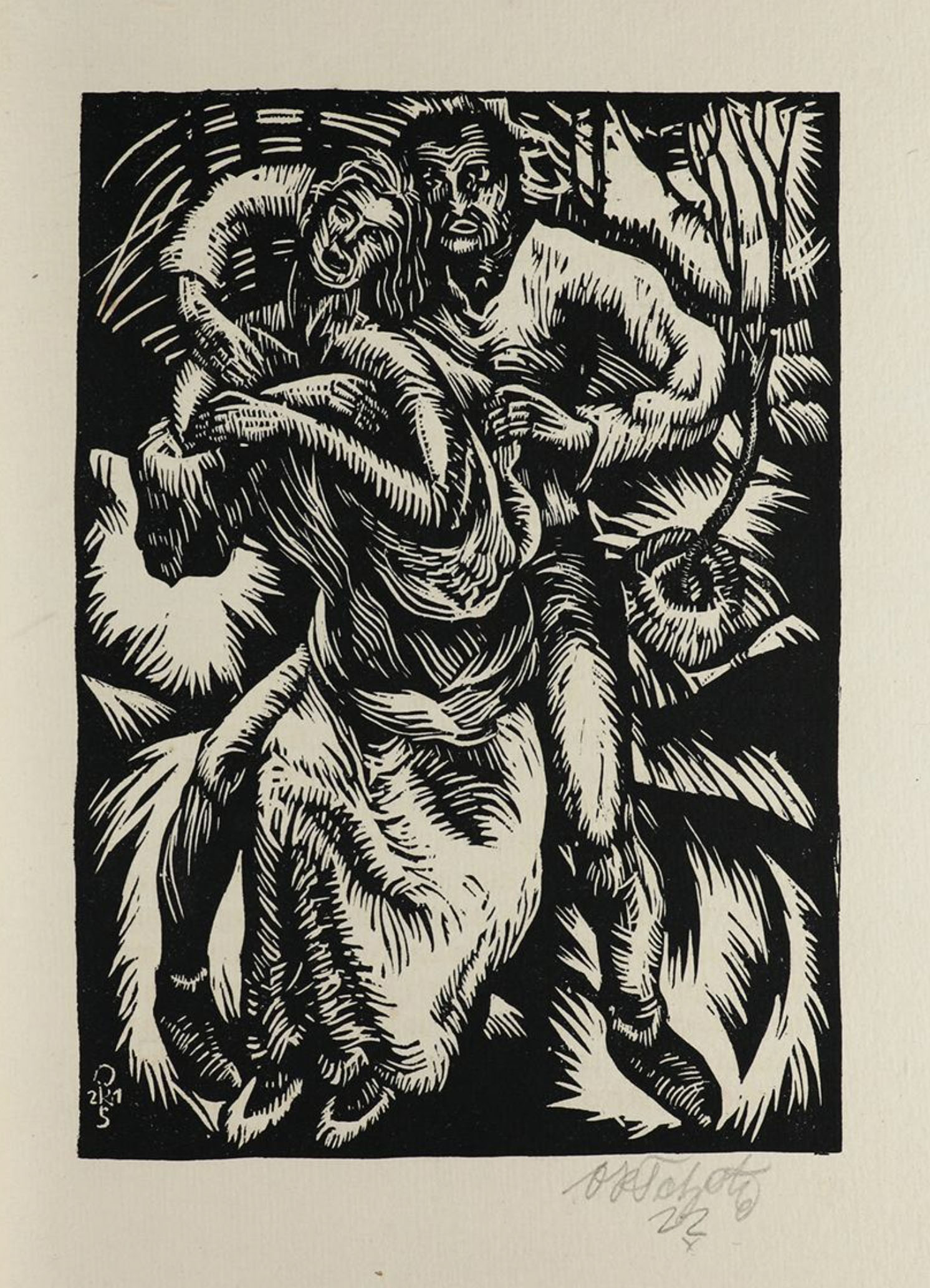

Perhaps Schatz in this woodcut with humans engaged in conflict over an ox-drawn cart is trying to illustrate Death’s contention, as you read below, that “every human created to completion has nine holes in his body; out of all these there flows such repellent filth that nothing could be more impure.” Even the man on the left, holding up a book (Bible?), can’t convince the shovel-wielders to stop the violence.

Ch 24 Death

…. He who asks for advice then will not follow the counsel given is not to be advised. Our wise words are lost on you. Now whether you like it or loathe it, We shall bring you the truth to light: listen who will.

Your short understanding, your clipped mind, your hollow heart, will make more of mankind than it has the power to become. …. Let recognise who will: every human created to completion has nine holes in his body; out of all these there flows such repellent filth that nothing could be more impure. … Strip the dressmaker’s colouring from the loveliest of ladies, and you will see a shameful puppet, a hastily withering flower, a sparkle of little durance and a soon decomposing clod of earth! …. Let love flow away, let grief flow away! ….

Ch 25 Husbandman

… How you destroy, maltreat, and dishonour noble mankind, God’s dearest creation, thereby reviling divinity! … Now if man were as despicable, evil and impure as you say, then truly, God would have worked an unclean and futile act. Had God’s omnipotent Hand created so impure and ordurous a work of man as you say, He were a shameful Creator. …

Sir Death, cease your pointless yapping! You sully God’s most splendid creation. … God formed him in His image, as He Himself proclaimed at the Creation of the World.

[Plowman lists the wonders of the human head : eyes, nose, mouth, brain.] Only man is in possession of reason, the noble treasure. He alone is the delightful form, whose like none but God is able to shape, and in which all skilled works, all art and mastery, are woven with wisdom. Let go, Sir Death! you are the enemy of man: that is why you speak him ill.

Ch 26 Death

… Now let Us accept your opinion that man has been endowed with every knowledge, beauty and dignity: he must, notwithstanding, fall into Our net; he must be drawn into Our snare. [Death lists the achievements on the human brian: grammer, logic, geometry, arithmetic, philosophy, etc.] These arts, and all those related, avail nought: every man must be felled by Us, scoured in Our fulling-tub and cleaned in Our rolling-press. Take my word, you riotous ploughhand!

Here Death welcomes a newborn, knowing full well that this infant will one day be felled by his scythe.

Ch 27 Husbandman

One should not meet evil with evil; man should practise patience, and have the teachings of virtue at his command. I shall tread this path; perhaps this will exhaust your impatience.

…. Now if trueness dwells in you, advise me in good faith, as though after a sworn oath: what direction shall my life take now? Previously I lived in dear and happy wedlock; where should I turn to now? To the secular or the spiritual state? Both stand open to me. My mind formed images of man’s many existences, then scrupulously weighed and appraised them: I found them all to be lacking, fragile and in sin. I am uncertain whither I should turn: every human station is tainted with affliction. Sir Death, advise! …. Upon my soul I say: if I knew that I would thrive in marriage as I have formerly done, I would live in that state for as long as my life continued. …

Lord of the Upper Regions, Prince of the Manifold Blessings, happy the man you endow with so spotless a bed-companion! He should look to Heaven and thank you with upraised hands every day. …

Ch 28 Death

To praise without end, to revile without purpose, at all times and places, is the custom of many. Praise and abuse should be meet and measured, that they be ready at hand when the need for one arises.

You praise married life beyond moderation. But We shall instruct you in the conjugal state, all pure women notwithstanding: as soon as men take a wife, so soon do they enter Our prison, two by two. … A wife strives all her days to become the man; if he pulls up, she pulls down; if he wants this, she wants that; if he wants to go here, she wants to go there – he shall have his fill of such sports and defeat every day. She can deceive, outwit, flatter, concoct, caress, grouch, laugh and weep in the blink of an eye; she was born that way. [Death goes on with the wiles of a wife.] If We did not wish to spare the virtuous women, we could sing and say much more about the ones lacking in virtue. So recognise what you are praising: you cannot tell gold from lead!

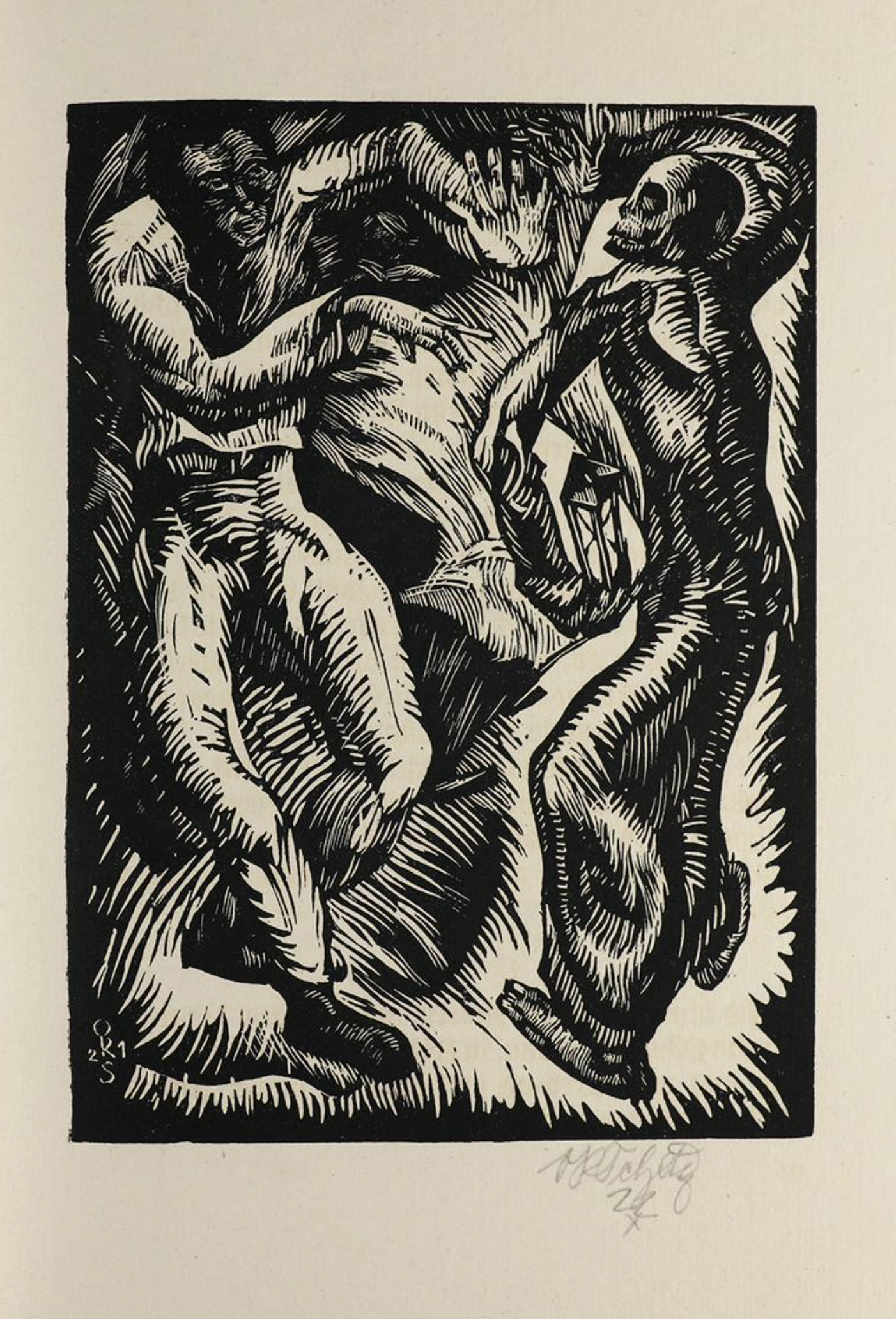

Here Schatz presents Death’s point of view that “as soon as men take a wife, so soon do they enter Our prison, two by two.”

Ch 29 Husbandman

... Your irrational vituperation against women, although it is made with their leave, is truly disgraceful for you and ignominious for them. In the writings of many wise masters one finds that, without a woman at the helm, no man may be steered to happiness; having a wife and child is not the slightest part of earthly joy. … Let anyone say who wishes: a modest, beautiful, chaste wife of untouched honour is above all earthly delights. I never yet saw a man, no matter how manly and spirited, who was not guided by a woman’s words. …

Now, there must be lead among gold, corncockles among wheat, counterfeits among coins, and she-devils among women: but do not make the good pay for the bad.

Ch 30 Death

… For you do not know that everything of this world is either desire of the flesh, or desire of the eyes, or pride in life. Desire of the flesh aims at lust; desire of the eyes at possessions or estate; and pride in life at honour. Possessions bring greed, lust causes lewdness and lechery, and honour brings arrogance and boastfulness. Possessions will lead to desire and fear, lust to malice and sin, and honour to vanity. Could you comprehend this, you would find vanity walking the whole of the world; and if joy or sorrow then befell you, you would endure it in patience and leave Us unreproached.

As well as an ass plucks the lyre, with such skill do you grasp the truth. That is why We are so sorely concerned for you. … For We, Death, remain Master here!

Ch 31 Husbandman

…. If we all depart this life, and all earthly beings have an end, and you are, as you say, life’s ending, then I reason: where life is not, there can never be dying and death – So where are you, Sir Death? Heaven is no home for you: it is given only to good spirits, and you are, after your own words, no spirit. Now when you have nothing more to manage on Earth, and Earth is gone for ever, then you must straight to Hell; where you must groan without end. Then shall both the living and the dead be avenged on you. …

Are all sublunary beings really so evil, wretched and vicious in creation and form? That would be to speak against God, an accusation never levelled against the eternal Creator since the dawn of the world. Hitherto, God has loved virtue, hated evil, and overlooked or punished sin. … You say that all earthly life and being must have an end. Yet Plato and other messengers of wisdom say that: all events involve the decay of one and the birth of another; recurrence is the universal foundation; and everything in the revolving earth and heavens is an effect eternally transforming between the two. With your swaying words on which no one may build, you intend to deter me from my complaint. So I refer myself and you to God, my Saviour. Sir Death, my undoer, God give you a dire Amen!

Are all sublunary beings really so evil, wretched and vicious in creation and form? That would be to speak against God, an accusation never levelled against the eternal Creator since the dawn of the world. Hitherto, God has loved virtue, hated evil, and overlooked or punished sin. … You say that all earthly life and being must have an end. Yet Plato and other messengers of wisdom say that: all events involve the decay of one and the birth of another; recurrence is the universal foundation; and everything in the revolving earth and heavens is an effect eternally transforming between the two. With your swaying words on which no one may build, you intend to deter me from my complaint. So I refer myself and you to God, my Saviour. Sir Death, my undoer, God give you a dire Amen!

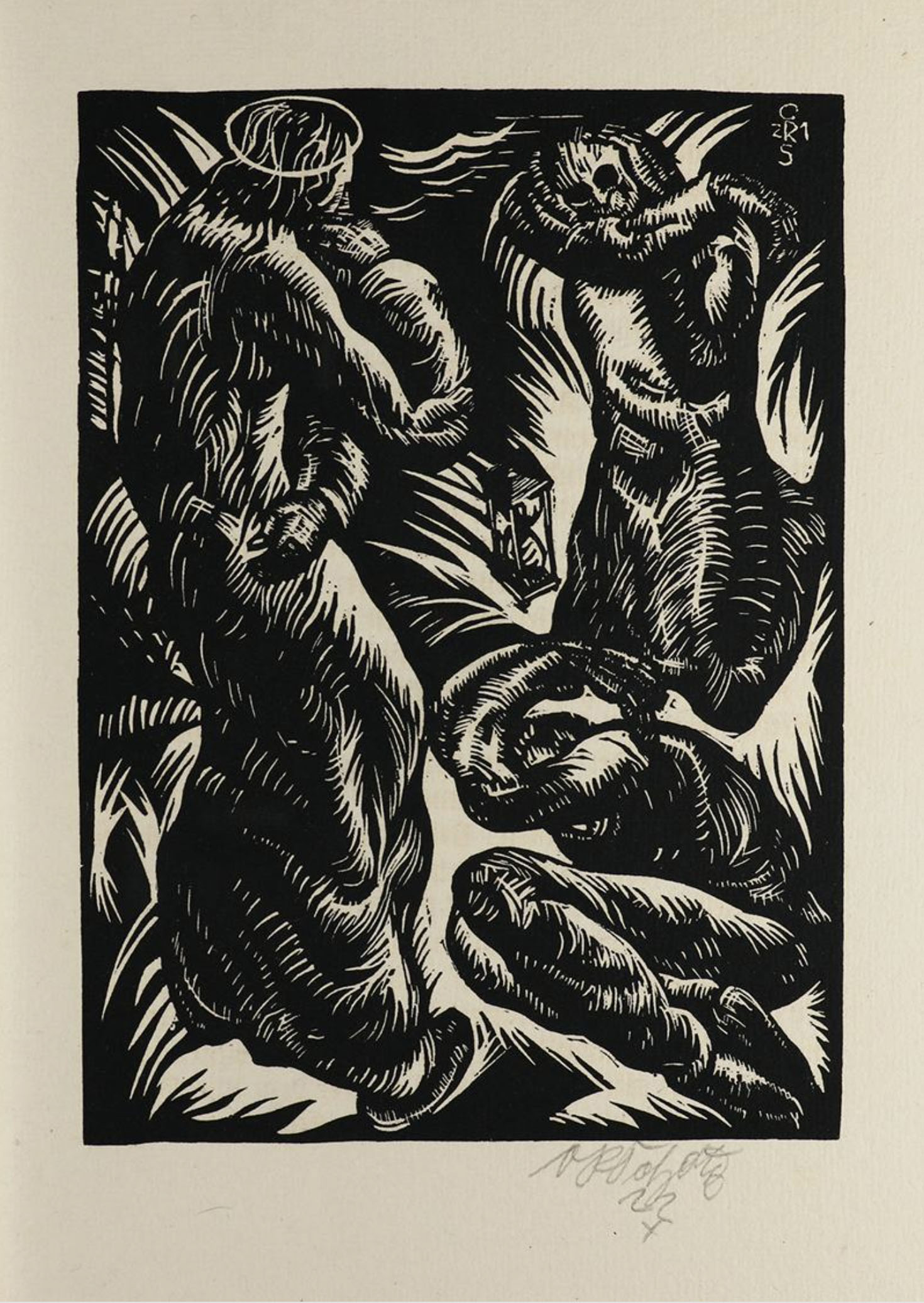

In the figures at the bottom of this woodcut show a certain resignation about the certainly of death. To their right a kneeling figure prays. But what of the central figure? Its that our Plowman? What does that gesture mean?

Ch 32 Death

… We have said and We say – and this by way of conclusion –: the Earth, and all it contains, is founded on temporality. … I have thrusted the whole human race into fire’s steady flame. The chance of finding a good, true, constant friend is almost as great on this Earth as that of grasping a light-beam. All humans are inclined more to evil than good. When someone does do good nowadays, he is acting from fear of Us. All people, and all their activity, are full of vanity. I have thrusted the whole human race into fire’s steady flame. The chance of finding a good, true, constant friend is almost as great on this Earth as that of grasping a light-beam. All humans are inclined more to evil than good. When someone does do good nowadays, he is acting from fear of Us. All people, and all their activity, are full of vanity. … a human cannot know when, where and how We shall suddenly overfall him and drive him the way of all flesh. This burden must be shouldered by master and servant, husband and wife, rich and poor, good and evil, young and old. …

So leave your complaining! Enter whichever rank you wish, you will step into affliction and vanity! Now depart from evil, and do good; seek peace, and hold on to it with constancy*; love a pure and clean conscience above all earthly things! And as we have advised you correctly, We shall accompany you to God, the Great, the Mighty, the Eternal.

Ch 33 The Judgement of God

Springtide, summer, autumn and winter, the four invigorators and upholders of the year, fell into disaccord and fiery dispute. Every one of them boasted of their beneficence in rain, winds, thunder, showers, and in all kinds of storms; and every one would be the best in his working.

Spring said that he revives all fruit into lush profusion. Summer said that he ripens and readies all fruit for harvest. Autumn said that he brings all fruit to collection in barns, cellars and houses. Winter said that he consumes and expends all fruit and expels all poisonous vermin. They boasted and quarrelled violently. But they had forgotten that they were boasting of powers granted them by God.

As you both are now doing. The plaintiff laments his loss, as though it were his estate; he does not pause to reflect that it was loaned by Us. Death boasts of his mighty powers, which he only received in fief from Us. This one laments what is not his; that one boasts of a power that is not immanent. However, the quarrel is not entirely unfounded. You have both contested well: the one is forced by his sorrow to lament, the other by the plaintiff’s attack to tell the truth. So plaintiff, yours is the honour! And Death, yours is the victory! Every man is obliged to give his life to Death, his body to the earth, and his soul to Us.

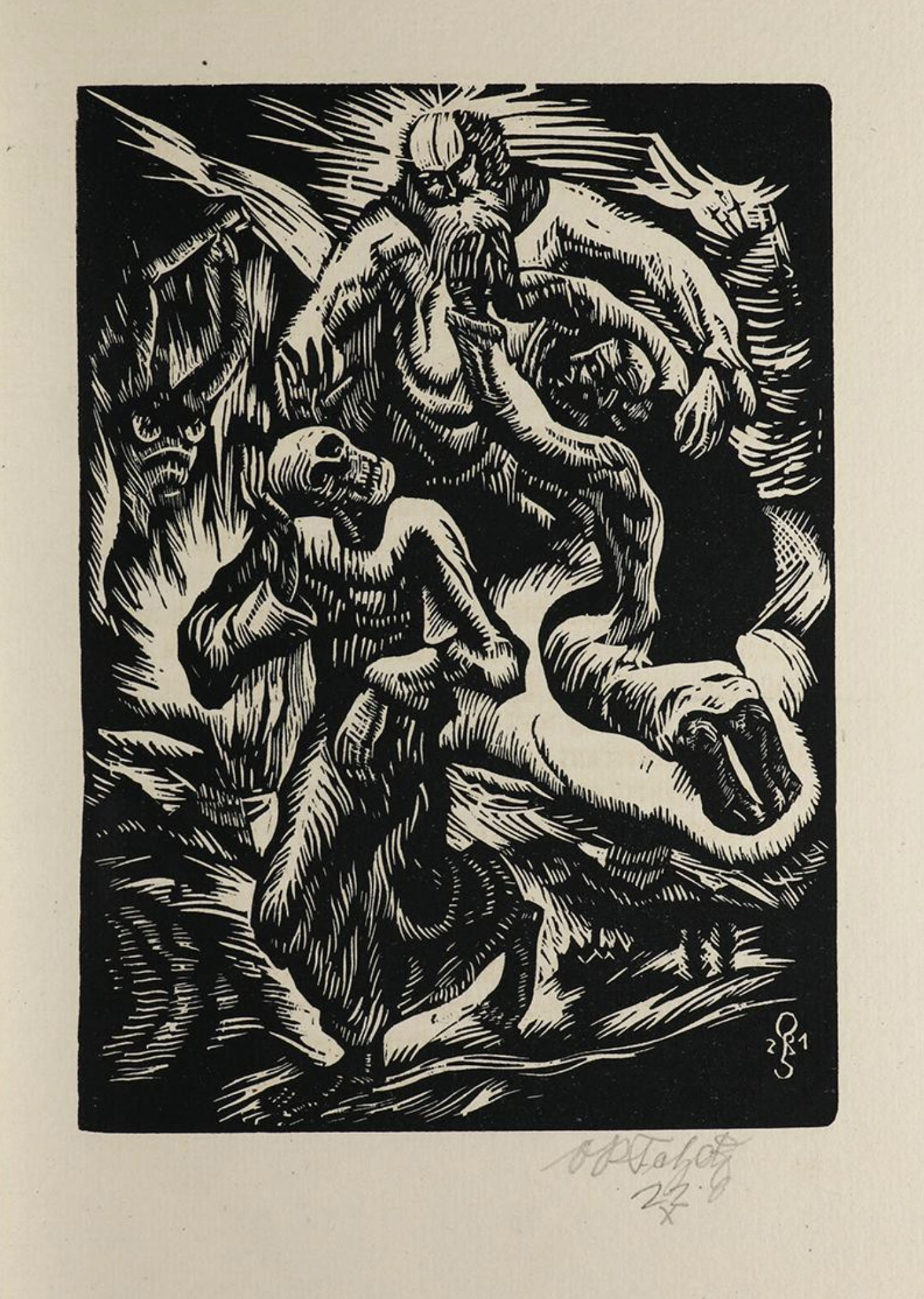

Here the Plowman’s prayer is answered: “Receive unto grace the spirit, receive in mercy the soul of my beloved wife! ” Meanwhile, Death, to whom God declares “yours is the victory,” quietly looks on.

Ch 31 The Husbandman’s Prayer for the Soul of his Wife

[He addresses the “God of God” in all of his manifestations, for instance:] Treasure, from which all treasures issue forth; Source, from which all pure springs flow; Guide, who leads none astray; Saviour for every ailment, to whom all things hive and hold, like bees to their queen; Cause of all things [always ending with] hearken to me!

… receive unto grace the spirit, receive in mercy the soul of my beloved wife! Give her eternal repose, bathe her with the dew of Your favour, preserve her in the shadow of Your wings! Take her, Lord, into complete sufficiency, where the slightest find the fulfillment of the greatest! Let her, Lord whence she is come, live in Your kingdom with the eternally blessed!

I ache for Margaretha, my chosen wife. Grant her, Lord rich in grace, that she see, behold, and take delight in herself in the mirror of Your Almighty, Eternal Divinity, the Light of all angelic choirs!

All that has its home beneath the Eternal Standard-Bearer’s banner, whatever creature it be, help me in saying with blissful intensity, from the depths of my heart: Amen!

★ ★ ★ ★

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/schatzs-der-ackermann-und-der-tod-woodcuts/trackback/