Richard Wagener: Naturalist/Wood Engraver

Introduction

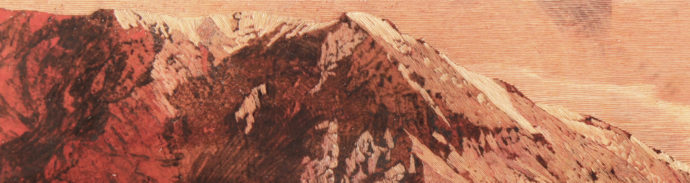

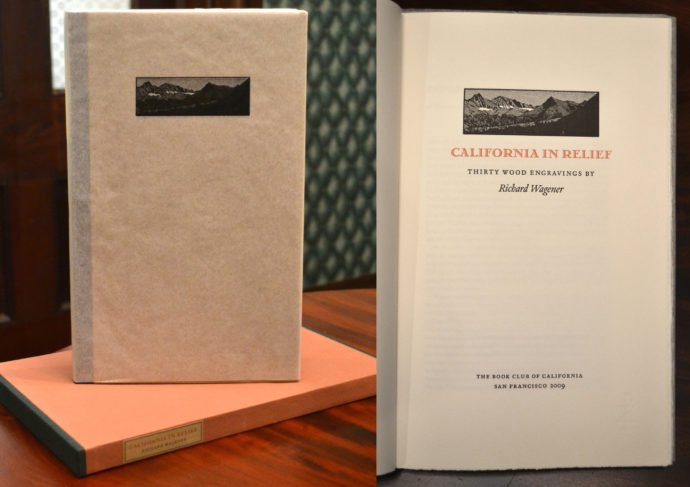

My excitement about acquiring copies of Richard Wagener’s two books of wood engravings–California in Relief (The Book Club of California, 2009) and The Sierra Nevada Suite (The Book Club of California, 2013)–stemmed from thinking of them as natural successors to Paul Landacre’s much-heralded 1931 book California Hills and Other Wood Engravings. In fact, Victoria Dailey in her preface to Wagener’s California in Relief writes: “In the realm of California printmaking, Paul Landacre (1893-1963) has been the undisputed master of wood engraving, creating sumptuous landscape prints and several illustrated books including his masterpiece California Hills (1931). Not since Landacre has any California artist achieved prominence in this challenging medium until Richard Wagener (b. 1944) began to explore it in the 1980s.”

Paul Landacre, California Hills and Other Wood Engravings (Bruce McCallister, Los Angeles, 1931), No. 150 from an edition of 500, signed.

So I immediately wanted to email him to ask if Landacre inspired his own California book. If only I had read more of Dailey’s essay where she said: “Soon after he began to make wood engravings, Wagener became aware of Landacre, whose work he appreciated. Nevertheless, he says that Landacre had no direct influence upon him.” So that effectively killed that way to approach Wagener. (Although later he did comment: “Paul Landacre is someone I’ve always admired. There is a distinctive style and clarity in his cutting that I find amazing.”)

Instead I proposed that I send Richard images of five wood engravings from the late 19th century to mid 20th century and ask him to comment. He responded: “I’ve been thinking about your proposal and am not sure how I feel about it. I’m not a critic. Well I am privately, but feel uneasy about making my value judgements public. The curse of the artist/critic is living up in your own work to the standards applied to others.”

But I assured him that I would not send him images of artwork of living artists, and he agreed to share his thoughts on each. I also included questions about his own work and working methods. Those responses turned out to be more enlightening than his comments to others’ work. So I’m going to start with Richard Wagener on himself.

Richard Wagener in his studio.

Interview

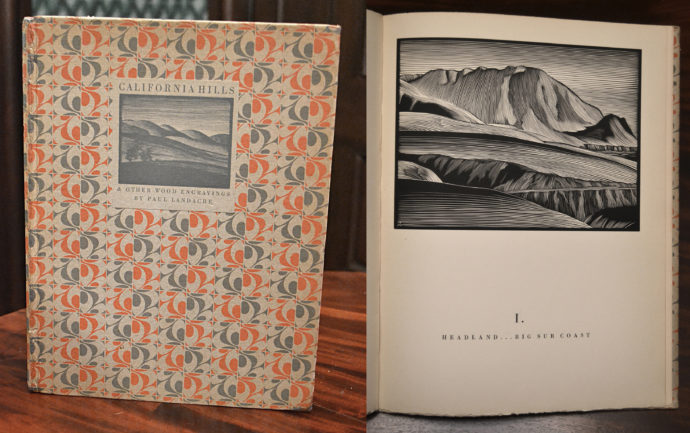

I began by asking Richard about his 1998 book Zebra Noise with a Flatted Seventh (Peter Koch, Berkeley, CA, edition of 70), which contained 26 short fictions by Wagener and 26 of his wood engravings each incorporating a letter of the alphabet. In particular I asked about one of his wood engravings of that period:

Richard Wagner, Shadow of the Hawk, wood engraving, 1984, 6 7/8″ x 5″

Can you tell me what you were trying to achieve with Shadow of the Hawk and what you learned in the process?

Early in my explorations of ways of bringing together disparate aspects of my background, undergraduate studies in natural science and graduate studies in abstract painting, I juxtaposed flora or fauna against a flat grid. This was at a time when I was rethinking conversations I had some years before with a sculptor in San Diego about Matisse’s approach to composition–every part of the field deserves consideration. Splashes of ink entered the compositions and there was a lot of thinking about also incorporating letter forms.

One day I was in a bookstore in Little Tokyo (Los Angeles) and took in the beauty of the books filled with all the wonderful Japanese characters. And with the beauty of the type was the mystery of what any of the characters meant. In my engraving I didn’t want to get tied down to a specific word or thought so I started playing around with abstract calligraphic gestures. Shadow of the Hawk seemed to be the first engraving that fully embraced the ideas I had been thinking about.

Wood engraving has long been used to illustrate fauna, going back at least to Bewick. How did Shadow of the Hawk fit in with that genre? How did it break with it?

When I first discovered wood engraving as a medium with which one could create a vast range of marks and establish tonalities, I had no intention of becoming a wood engraver. I was only interested insofar as the use of these tools and the wood surface could be of use in exploring ideas. That is why I deliberately chose not to buy the David Sander book on how to do wood engraving. As he was the only known source of engraving materials, the wood engravings I saw were the ones he would print in his catalogs, including a Bewick print. Beyond that I was pretty clueless as to the history of the medium. There was no one actively engraving in Los Angeles and no one to talk with about engraving in wood. With the exception of seeing Barry Moser’s illustrations of Alice sometime in the mid 1980’s, it was not until David Sander offered Simon Brett’s 1992 book Engravers Two that I had a chance to see what many others were doing with this medium.

Being essentially unaware of the genre of wood engraved fauna, it was not something I stopped to consider during the early years of exploration. My efforts were focused on making something work for me. Part of this was naiveté and part of it was not wanting to be influenced while finding my way. It took many years to become comfortable with what I was doing. After I found a certain level of comfort with what I was achieving, it became easier to then look at the historical precedents in the medium and appreciate their achievements.

Richard Wagener, California in Relief, The Book Club of California, San Francisco, 2009, No. 79 from an edition of 300, signed.

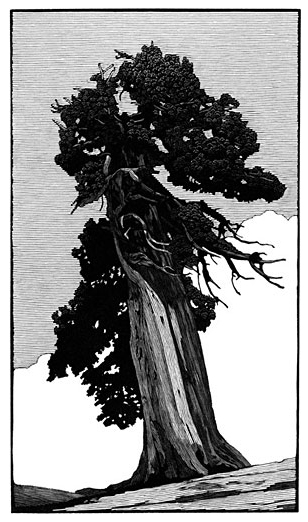

What attracted me to your California and Sierra suites of images–such as Outlook Tree–were the calm each radiated, the focus on silhouettes, and the picking out details in the shadows. Can you talk about each of these three properties?

My love of the California landscape was formed by all the time I spent during my childhood with my grandfather in the high desert and up in the Sierra, time that left an indelible mark. And yet, it was not until I hiked up around Shuteye Peak, south of Yosemite and overlooking the Ansel Adams Wilderness area, that I felt the need to bring my experiences to bear on what I was engraving. And I found that like John Masefield’s sea, the Sierra invokes feelings for me that then beg to be engraved. Since my formal art training was almost exclusively graduate studies in abstract painting, the Sierra imagery challenged my abilities as an engraver. The felt experience of hiking throughout this area was compelling and the question of whether this could be expressed in wood captivated me.

Richard Wagener, Outlook Juniper, wood engraving, 5″ x 2 7/8″, from The Sierra Nevada Suite.

The Outlook Tree (or Outlook Juniper) is a survivor, emerging out of cracks in the glacier–polished granite–enduring over hundreds of years in an environment of scarce resources and harsh weather. I find a beautiful solitude on these rock outcroppings and sparse areas. My experiences up in the Patriarch Grove of Bristlecone Pine in the White Mountains with no one else around and walking among trees that are over 4,000 years old are beyond words. The idea is to try and convey the dignity of the tree as it stands against the wind and elements. I want to be very specific about the tree that haunted my recollection of the time and place. Here, as in many other engravings, I have pared away other elements that may interfere with the attention this tree deserves. So the context may be altered to enhance the appreciation. And there is much to be appreciated in the shadows. Unless there is a reason for a more dramatic effect, the shadows help round out the personality of the subject.

As I wrote in my notes for California in Relief, I have gone back and tried to find some of the trees I’ve engraved and I couldn’t find them. This has made me wonder if it was the particular day, or time of day, that brought my attention to certain things, things that at other times might have been missed.

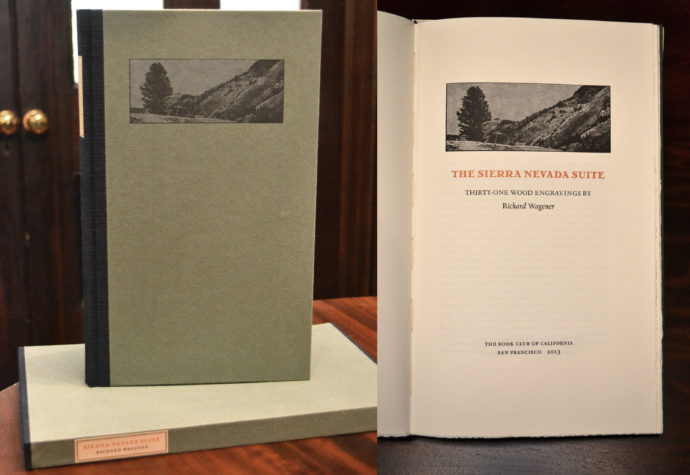

Richard Wagener, The Sierra Nevada Suite, The Book Club of California, San Francisco, 2013, No. 182 from an edition of 308, signed.

With your work for Vestige (Mixolydian Editions, 2015) you again appear to have sought out something meditative. Is there something common “thread” running in your work? Yet how was making images for Vestige different from what preceded it? Did it break new ground for you either in process and/or open your eyes to possibilities for future work?

When I was developing the text that would appear in Zebra Noise with a Flatted Seventh, I began to learn how editing could pare down my stories to the essentials. The same thinking guided my writing for Cracked Sidewalks, where a main concern was how many words were needed to tell a story. This approach was also taken in one of the engravings where the question became “how many lines do I need to engrave to sell the image?”

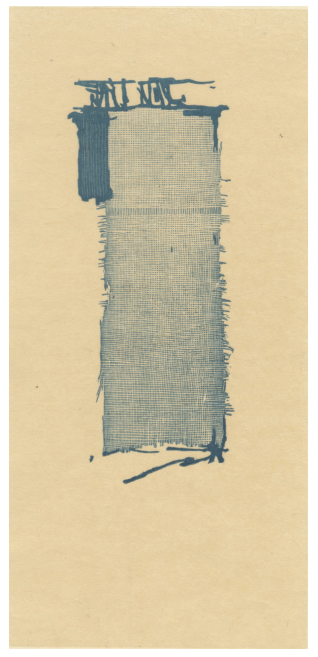

Richard Wagener, wood engraving from Vestage.

While printing the images for The Sierra Nevada Suite, my thoughts drifted back to an idea from long ago, the idea of a loom and threads. The question then became, “how many threads does it take to make a weaving?” The three drawings exploring this idea were on my table as the remaining images were printed. The later engravings based on this thinking ultimately yielded a suite of sixteen conceptual prints printed along with a poetic response from Alan Loney, a New Zealand poet residing in Melbourne, Australia. With the exception of the first three drawings, all the subsequent engravings developed organically during the process of engraving and deviated from the loose markings initially made on the block. The last image in the series was started with only an idea in mind. There was no drawing or marking on the block to guide the engraving.

The resultant book was titled Loom (Nawakum Press & Mixolydian Editions, 2104). The deluxe edition, sixteen copies, came with one print from the book so that no two copies were the same. I decided to do a special print that was not from the book. If the print followed the same format as the images in the book it would seem to raise the question as to why it was not included in the series. The solution was to approach the idea of weaving from a different vantage point. Whereas the Loom series was dealing more with the threads coming together into a weaving, the second series was thinking more about the ultimate fate of this activity and the beauty in weathered and distressed textiles. The new drawings gave way to five engravings of this modified theme. Alan picked up on the new ideas and again wrote a poetic response. This became Vestige.

Is there a common thread running in my work? For me, a change of medium requires confronting three basic problems. The first is the very rudimentary problem of how to do it and getting comfortable with the tools and materials in order to understand the basics of the medium. This seems pretty simple. Putting in some time and effort one can achieve a reasonable level of familiarity and comfort. The more difficult and problematic questions concern what to do with this medium and why. These two questions have never gone away, and I am continually confronted with them. What to do was initially solved by the determination to bring together the disparate aspects of my background. It took a long time thinking to find out what that bringing them together might look like. And even then there was a gradual evolution of that solution as I continued to reflect on the question.

When the blocks for Zebra Noise were completed, 1993-94, I needed a sense of mental separation from the works of the last decade. A new answer had to be found. Flora replaced fauna and the representational element was freed from the specimen box and took on a more prominent role. In time another answer knocked on the door and asked to be considered. Then another. I believe in the idea that art comes from art. The more I work, the more ideas appear. As I think about what I am doing I am always trying to answer for myself why I am doing it. So it has been a meditation on who I am, what does it mean to be scratching the surface of a wood block, and what is the nature of this medium.

As requested, Richard later emailed me images to illustrate his working procedures.

I don’t do many finished drawings on paper. My best drawings are on the block.

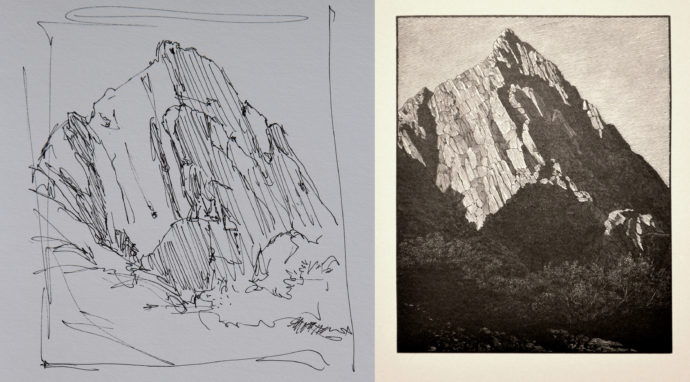

Richard Wagner, sketch for Behind the Lake (left) and image as it appears in The Sierra Nevada Suite (right). Wood engraving, 5″ x 4″.

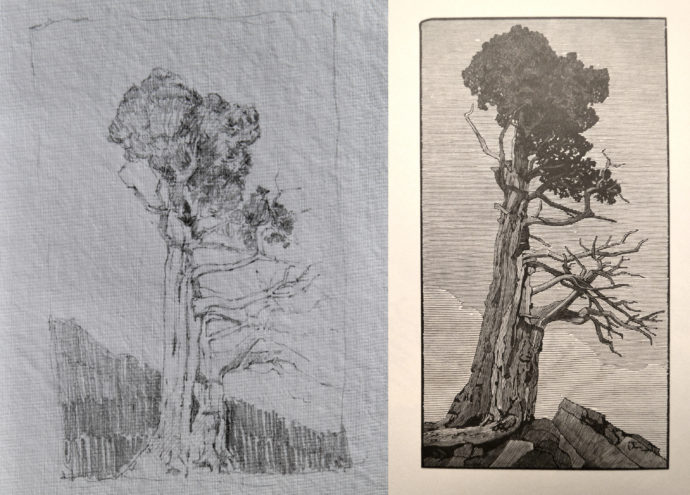

Richard Wagner, sketch for Sentinel (left) and image as it appears in The Sierra Nevada Suite (right). Wood engraving, 5 1/2″ x 3″.

[Richard then sent me a picture of a block in progress.]

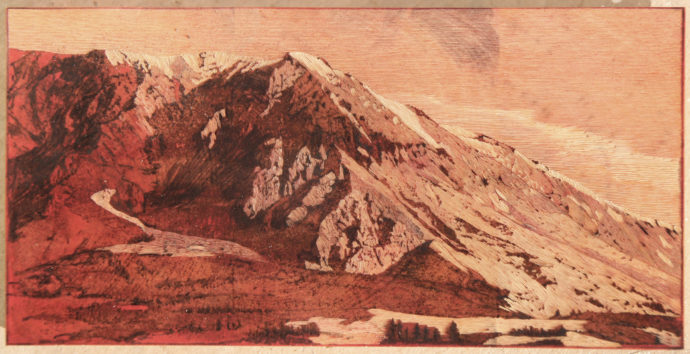

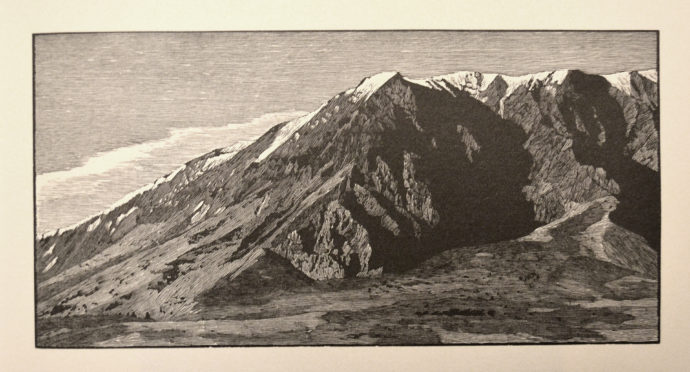

(Above) Partially cut block for (below) Richard Wagener’s Eastern Sierra Morning, wood engraving, 3″ x 5 15/16″

On engraving a block

I don’t proof my blocks during the engraving. I put as much information on the block as I think I might need in order to not get lost. Then I mentally figure out how I want to approach the engraving and then go for it. That is not to say there is never some refinement at the end, but reworked blocks often just end up as reworked blocks and lack the freshness of a well engraved image.

With one of the prints in The Sierra Nevada Suite I sharpened the tools, took a sample of wood and checked to see how the tools were cutting, how I was cutting on this particular morning. Based upon that information, I figured out what I was going to do, which tool I would use for certain areas. When I felt comfortable with this preparation, I started engraving the good block. However, about five lines in I realized that this wood was cutting differently than my sample wood. At that point I was committed to those lines and had to rethink everything else to get me out of the mess. All wood cuts in its own way. Sometimes the best laid plans go awry.

Work in progress

The current project is a book: Exoticum, Twenty-five Desert Plants from The Huntington Gardens. I’ve printed all the images and now I’m printing the titles for the images and the text. A friend who writes for National Geographic and teaches at the Graduate School of Journalism, UC Berkeley, has written an essay for the book. The official publication date is January 2017 and will show at the Codex Book Fair & Symposium. Perhaps the binder can get me an advance copy to show at the APHA conference.

Wood Engraving critique

I sent Richard images of five wood engravings in my collection, presented in ascending chronological order. I tried to seek his thoughts on prints that illustrate a progression of what wood engravers were trying to accomplish from the 1880s to the 1950s.

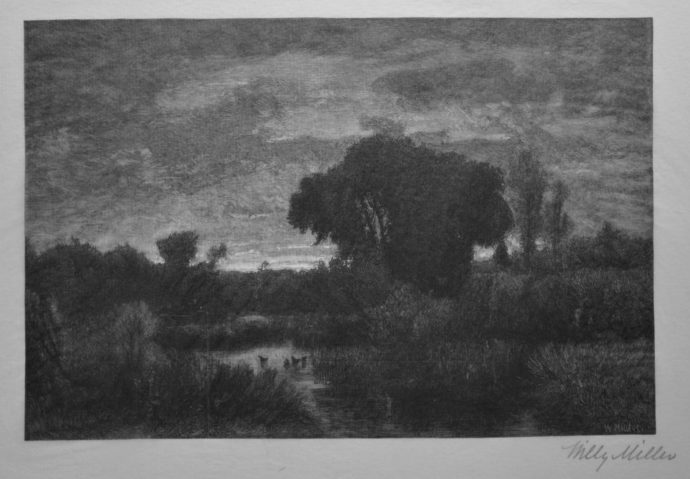

William “Willy” R. Miller (American,1850-1923), Sunset, wood engraving, c.1886, 4 5/8” x 7”, japan paper, After a painting by George Inness (American, 1825-1894)

This seems to be engraved from a photographic copy of the painting. The style at the time was to engrave the entire block, seemingly using few small tools, such that the value range is compressed and there are no areas of solid black or of pure white. This works well for a number of Inness paintings. I remember seeing an exhibition of Inness’ paintings in the mid 1970’s, and some scenes of evening deep in the trees were almost monochromatic. The use of small tools to create stippled tonalities seems to be a good way of translating painterly techniques into print. A highly linear rendering would lose some of the subtleties.

The point was to faithfully reproduce the original in a different medium and didn’t allow the engraver to explore their own personality. I’ve read about practices at the large engraving workshops such as Harper’s whereby a large engraving could be done by four different engravers, each working on one-quarter blocks that would then be bolted together and printed. The engraving style was so tightly established that the work of different engravers was interchangeable.

[I’ve made several posts on late 19th-century American wood engravers. Here’s a link to “Interpretive Wood-Engraving: Interview with its Author.”]

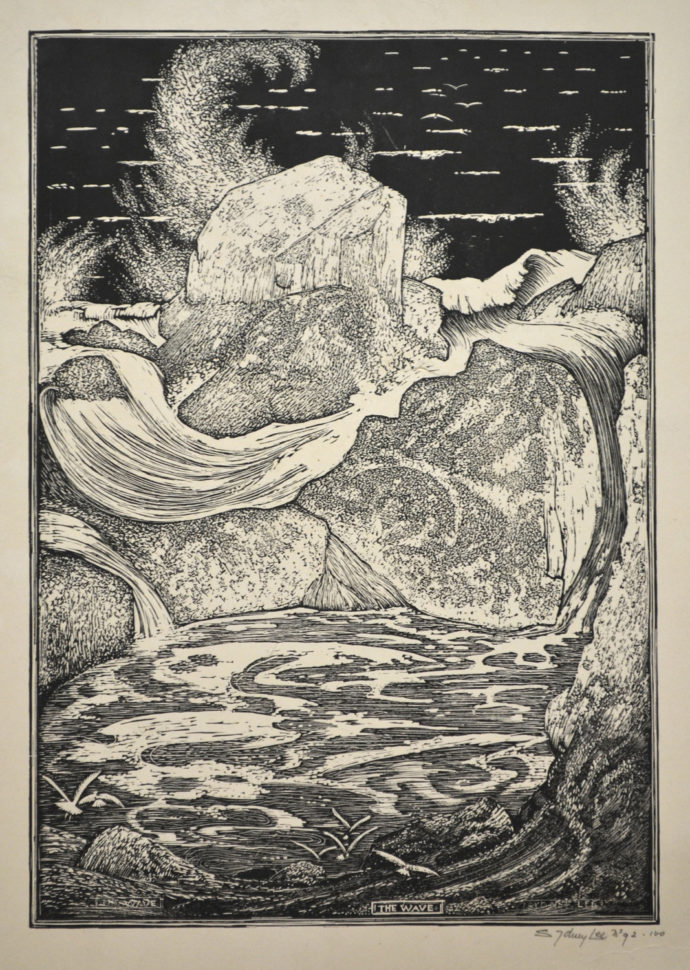

Sidney Lee (British,1866-1949), The Wave, wood engraving, 1914, 13 3/4” x 9 3/4”

This seems to be a departure from the prevailing approach to a subject using wood engraving that captures more of a woodcut appearance, invoking the Ukiyo-e sensibility. I like that it doesn’t conform to what a more mainstream wood engraving of the time might look like.

[Indeed The Wave was a departure for Sydney Lee at the time. But from 1904-10 he made a number of color woodcuts strongly influenced by Japanese printmaking. To read more about Lee, please go to my blog post: “Sydney Lee, an Obscure British Printmaker.“]

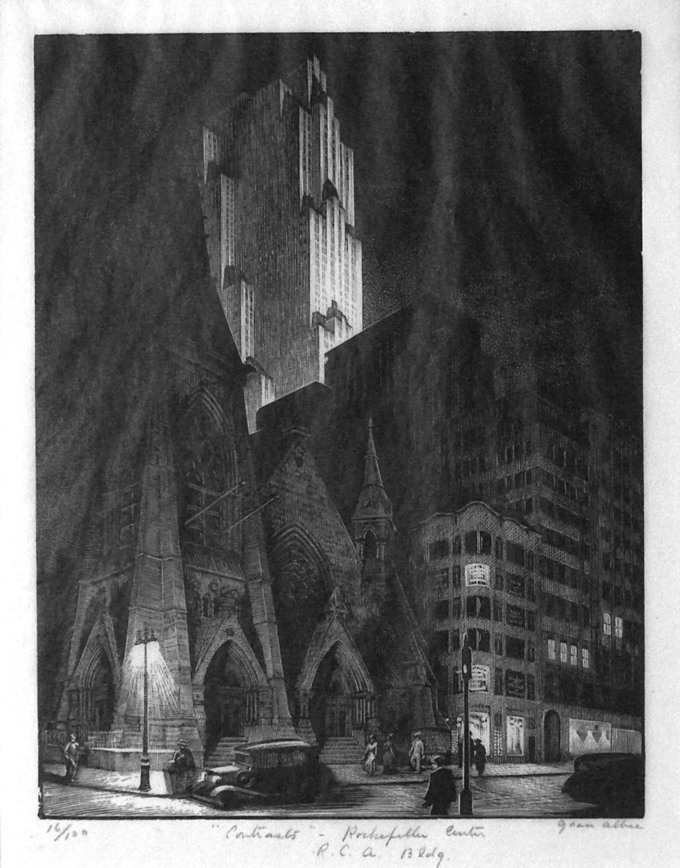

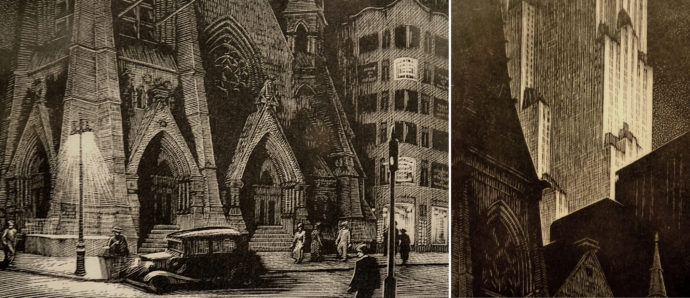

Grace Albee (American,1899-1985), Contrasts – Rockefeller Center R.C.A. Bldg, wood engraving, 1934, 7” x 5 1/2”, 16/100

Despite being a dark scene, for me this is a very bright print that captures what it is like to walk around midtown Manhattan late at night when the ambient lighting hides the stars. The contrasts are plenty: the light and the dark, the old and the modern, the secular and the religious. The scan of this print looks like the print is on perhaps a thin gampi paper that has buckled. It is hard to tell what is creating the light reaching up into the sky. Even the rendering of the car at the corner contrasts with the engraving of Rockefeller Center. I would like to see the print in person to be able to fully appreciate the engraved marks.

Two details from Grace Albee’s print Contrasts.

[After I sent him two detail images from the Albee print, he wrote:] The details from Contrasts seem to show a very sensitive printing of the block with the black of the building being so much denser than the black of the sky. Nice use of make-ready. I like this print very much.

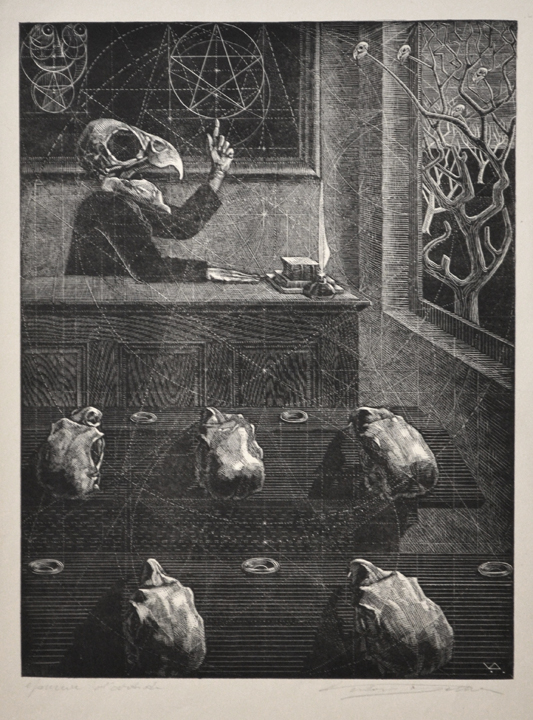

Victor Delhez (Belgian,1901-1985), Scherzo in Gold, wood engraving, 1948, 11 3/4” x 8 7/8”, inscribed “epreuve d’artiste,” small edition

Not sure what this about. Studies in Euclidian geometry or the occult? But nicely rendered. Perhaps this is the engraving that one wonders about the longest.

[This intriguing wood engraving was purchased from Bill Carl. He devotes a page to Delhez on his website: http://www.williampcarlfineprints.com/artist/delhez/engraving/]

Leonard Baskin (American,1922-2000), Death of the Laureate, wood engraving, 1957, 11 5/8″ diameter, a/p

Leonard Baskin (American,1922-2000), Death of the Laureate, wood engraving, 1957, 11 5/8″ diameter, a/p

Seems to be a hybrid of woodcut sensibility coupled with wood engraving. This is not to diminish black-line engraving, but it has the feel of many woodcut artists from the 50’s and 60’s. Baskin has no peers for this visceral approach, although Jacob Landau, a student of Baskin’s, mined similar territory very successfully. This certainly exploits a wide range of wood engraving possibilities. The tension between the two approaches enhances the effect.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/richard-wagener-naturalistwood-engraver/trackback/