Rethel’s Death as Counterrevolutionary Meme

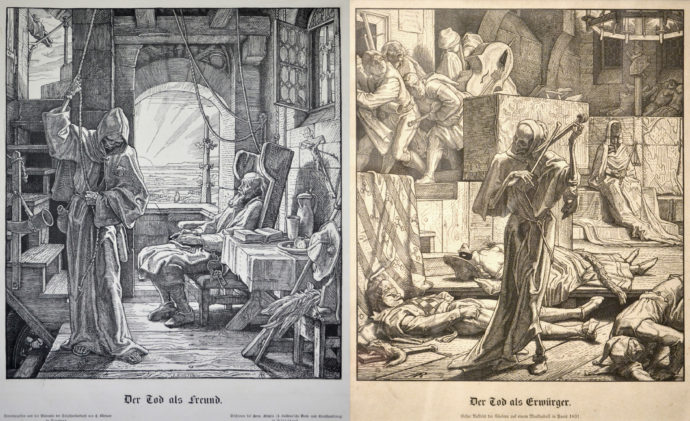

Two 1851 wood engravings adapted from drawings by Alfred Rethe.l LEFT: Richard Julius Jungtow (German 1828-after 1851), “Death as a Friend,” 12″ x 10 3/4″. RIGHT: Gustav Richard Steinbrecher (German, 1828-1887), “Death as an Enemy” (The first outbreak of cholera at a masked ball in Paris, 1831.), 12″ x 10 3/4″

The Want

Artist Alfred Rethel (German, 1816-1859) first grabbed my attention in 1985 when on a visit to San Fransisco I saw the exhibition “Ars Medica: Art, Medicine and the Human Condition.” (It originated at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.) This pair of wood engravings on the ying/yang of death–based on Rethel drawings–mesmerized me. Not wanting to forget those images, I bought the catalog. Some day, I promised myself, I’ll add copies of each to my then budding print collection.

Twenty-one years later (patience is a virtue for a modest-pocketed collector), I purchased Der Tod als Erwürger, thanks to an eBay listing that omitted Rethel’s name. Only the engraver’s name–Steinbrecher–was mentioned, and for better or worse that accomplished technician is long forgotten. Hence no one bid against me. Then 12 years later (2016), while on a trip to the Netherlands, late-night internet browsing brought me to an AbeBooks.com listing by a British dealer for Der Tod als Freund. The text under both images matched that found in the “Ars Medica” catalog. So I’m fairly certain that my pair is from early, maybe original, printings. Both images were quite popular and had a number of subsequent editions. (Der Tod als Freund had undergone some conservation–mending and probably whitening, which may account for dulling of the ink.)

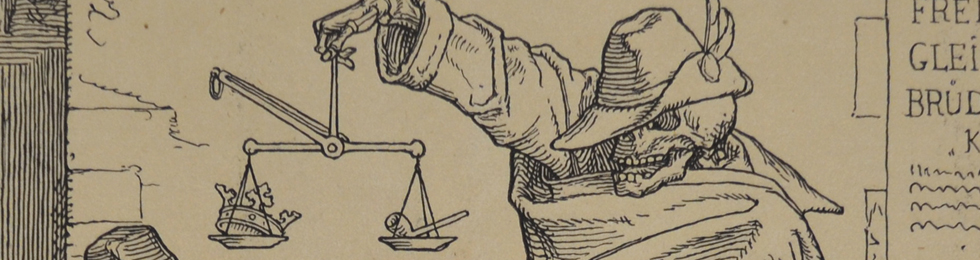

My dear friend Jay Fisher, former curator of the Department of Prints, Drawings and Photographs of the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA), was responsible for another Rethel quest. Years ago (it could have been soon after I saw the Rethel’s in San Fransisco) he introduced me to a book by Rethel containing six wood engravings of death fomenting revolution in Europe, much of which was undergoing political turmoil in the 1840s. The Museum acquired its copy in 1973. Again I was fascinated, but one plate (No. 3) held me back. Death is holding a scale–something a money lender might do–in front of a building where a Star of David hangs as a shop sign by a doorway. To me the image of Death manipulating a monetary transaction near a Star of David was clearly anti-Semitic. I was offended, and I turned down opportunities to purchase a copy.

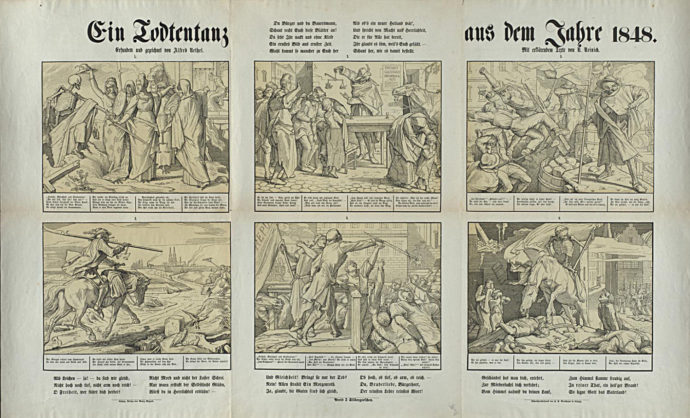

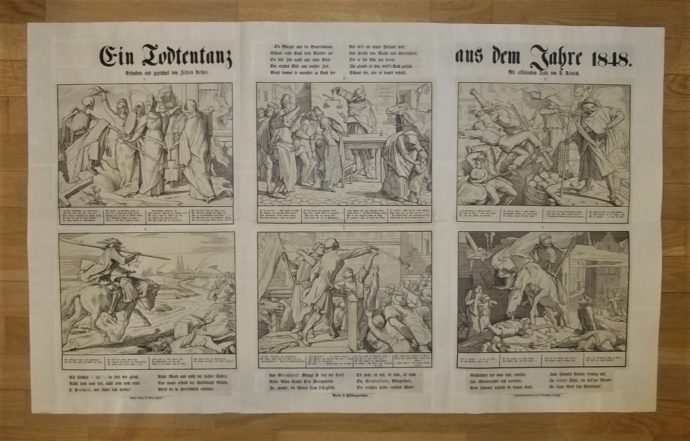

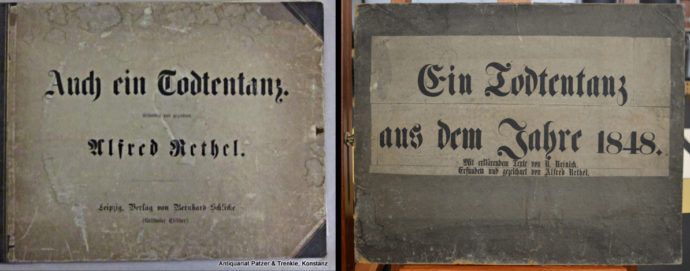

Yet the itch was there. Occasionally I would browse AbeBooks.com for the book Auch ein Todtentanz (Also a Dance of Death). The hardest thing was figuring out what was a first edition. Jay didn’t know if the BMA’s copy was a first. In my online searches I came to realize that that Rethel’s suite of prints was also issued as a broadsheet, which went by the title Ein Todtentanz aus dem Jahre 1848. Since I don’t like to duplicate what the Museum has, I started to gravitate to wanting the broadsheet, which had the same six images and text as the book. Initially the book and the broadsheet were created from the same blocks and letterpress type, just arranged differently. (Later there were lithographic versions of the book.) I suspect the major difference between the book and broadsheet editions–besides the format–was the quality of the paper, the books having better paper (less likely to brown and become brittle over the years.)

No surprise I eventually bought a copy of the broadsheet–just this May. First I’d like to describe how I made my choice and then present Ein Todtentanz aus dem Jahre 1848 plate by plate with translation of the text with discussion of the iconography–Star of David and all–plus a brief attempt to put this important suite of prints into historical context.

The broadsheet was first published in 1849 by Georg Wigand (German, 1818-1858) and printed by F. A. Brockhaus, Leipzig. It measures 28 1/8″ × 45 7/8 “. This copy is in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The Choice

I didn’t realize it until I reviewed stored messages that it took over two years from the time I first saw the listing for the broadsheet Ein Todtentanz aus dem Jahre 1848 on AbeBooks.com by Antiquariat V.A. Heck, a book dealer in Vienna, Austria, and my purchase from Heck in May, 2019.

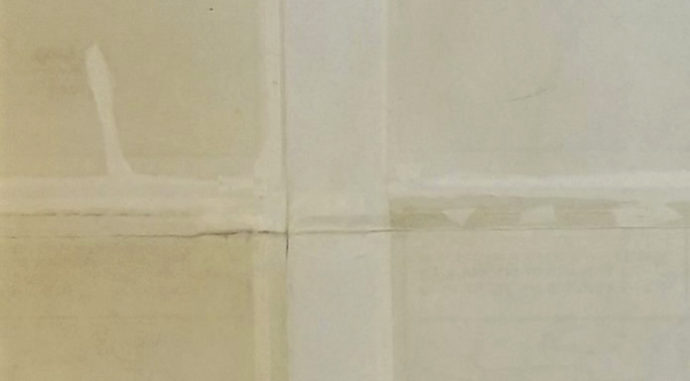

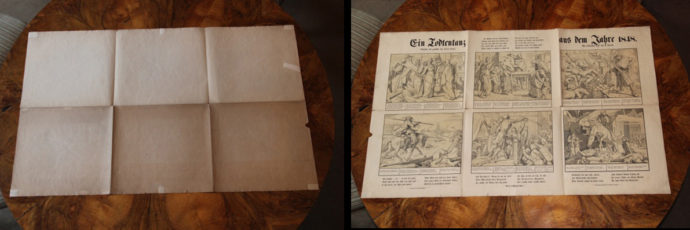

At my request in February 2017, Heck sent me these photos of its Todtentanz. Uta Schweger from Heck wrote: “The fold lines are in general in a good condition, some small tears in some corners and at some ends.”

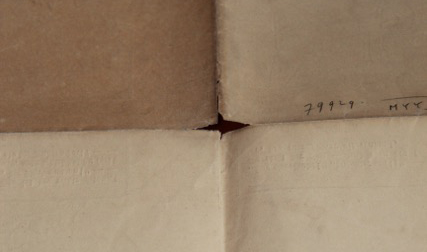

The folds are clearly visible as is the darkening of the reverse side. The closeup shows the some sections of the reverse are darker than others, and where the folds intersect there’s a break in the folds. Also note that below the horizontal fold the impression of the letterpress type (a commentary that appears below each image) is visible. The importance of which will become evident shortly.

These images alerted me that, should I purchase it, conservation would be needed. So I consulted Thomas Primeau, who had been chief conservator of the BMA and in 2017 was working for the National Archives. In an email he wrote: “I have always thought that these were interesting prints, I didn’t know that the series was also printed on a single sheet. The condition appears to be stable, but somewhat deteriorated with noticeable darkening on the reverse and tears. At the minimum, I would recommend repairing the tears, but if the paper is very brittle, then you might consider a washing/de-acidification treatment. Without seeing the work in person, I would say the range for conserving the print would be $250-$500. It is probably safer to store the work open as repeated folding could cause more tearing.”

Not sure I wanted to commit to costly conservation, I hesitated to make a purchase. Not surprisingly that would cost me.

Then in May 2019 another Austrian book dealer, Matthaeus Truppe Buchhandlung & Antiquariat in Graz, listed another copy of the broadsheet for about half the Heck price. When I wrote to this dealer to request images, I also asked: “I would appreciate if you could explain where your item falls within “Ein Todtentanz” edition history.” Truppe responded: “There was a Volksausgabe (Popular edition as a poster) which was printed by Brockhaus but edited at Wigand between the 4th and 5th edition [of the book that Wigand in Leipzig published]. I think this is a copy of the so called Volksausgabe.” (I’ll elaborate on the broadsheet’s publication later.)

Soon after viewing the broadsheet offered by Truppe, I retranslated the German text of it’s listing in AbeBooks.com. In part it read: “The text and the six images of the dead were mounted on a sheet in the form of a poster.” Especially from the back you can see that, where the woodcuts and the texts are mounted, those areas are darker than the surrounding paper. But the offering from Heck didn’t appear to be have that issue. Check out the detail of the Heck copy where you can see the letterpress impression on the back.

Detail of the reverse of the Truppe offering. Note that the impression of the type under the fold is not visible.

So I asked Truppe: “Was this trade edition issued this way–the blocks and text printed separately and then mounted on a larger sheet of paper–or has your item undergone an extensive restoration effort? I’ve seen another example that seems to have been printed onto a single piece of paper.” The response from Truppe: “Our copy was cut and mounted on a new sheet.”

At that point, I decided to again contact Heck, which fortunately still listed the Rethel broadsheet. I wrote: “Recently I contacted a second seller of the broadsheet only to find out it had undergone major reconstruction. So maybe a fragile version is not so bad, although I will have to have a paper conservator look at it.” Because of the unknown conservation cost, I offered 75% of the Heck listed price. Dr. Uta Schweger at Heck agreed.

The Object

The six blocks of Ein Todtentanz aus dem Jahre 1848 present a cautionary tale of how the working classes can easily be incited to revolt by an unsavory personage, in this case by Death himself. Much of central Europe was in tumult at the time. While the upper classes were seeking franchise for themselves, the lower classes were deemed by many to be too easily manipulated to be trusted with the vote. So Rethel’s Todtentanz was immediately popular for its counterrevolutionary message. At least 10,000 copies were printed.

Later I’ll detail the historical context and even suggest that Rethel had misgivings about his reactionary message, but first here are the six wood engravings. I’ve gotten the German text translated. The broadsheet has an introductory paragraph; then each plate had its own commentary written by the poet Robert Reinick (German, 1805–1852). I’ll also isolate details from each plate that provide clues to the reading of each. Certainly viewers contemporary to its publication could read the images, but 21st-century viewers could use some aids.

I immediately sent my copy of Ein Todtentanz aus dem Jahre 1848 to a paper conservator in the Washington suburbs (Thomas Primeau had moved to a position in Philadelphia) soon after it arrived in mid-June. It was in a more fragile state than I expected. Hence the images that follow are from the set at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

I want to thank Ellen von Seggern Richter for the translations. And thanks Morgan Dowty, Curatorial Assistant in the BMA’s Department of Prints, Drawing and Photographs, for allowing me to photograph the Museum’s Rethels. The plates’ titles and names of the plates’ wood engravers are from the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s listing for the broadsheet.

Notice that each of the six blocks that make up Rethel’s Todtentanz was cut by a different engraver. Wood engraving was a prime medium for book illustration in mid-19th century, and wood engravers’ jobs were to reproduce–not interpret–images sent to them by publishers. Imagine that Rethel supplied publisher Georg Wigand in 1848 with drawings that were then given to six different engravers, maybe with the advice and consent of Rethel, maybe not. Rethel no doubt got to see and, if necessary, amend proofs of their work. Two of those engravers–Richard Julius Jungtow and Gustav Richard Steinbrecher–would later cut Rethel’s 1851 wood engravings Death as a Friend and Death as an Enemy.

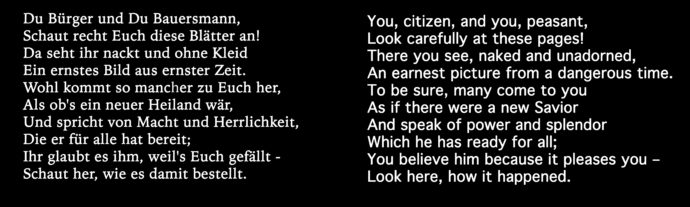

Prologue

On the broadsheet the prologue appears between the words of the title.

PLATE 1: Der Tod entsteigt dem Grab (Death Rises from the Grave)

Reading Plate 1

Two articles provide my guides to reading Todtentanz details:

Kerrianne Stone, “Uprisings, epidemics and spontaneous deaths,” University of Melbourne Collections, Issue 9, December 2011. Stone is Curator, Prints for Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Albert Boime, “Alfred Rethel’s Counterreolutionary Death Dance,” The Art Bulletin, Vol. LXXIII, No. 4, December 1991. Boime (American, 1933-2008) was a long-time professor of art history at the University of California, Los Angeles and wrote more than 20 art history books.

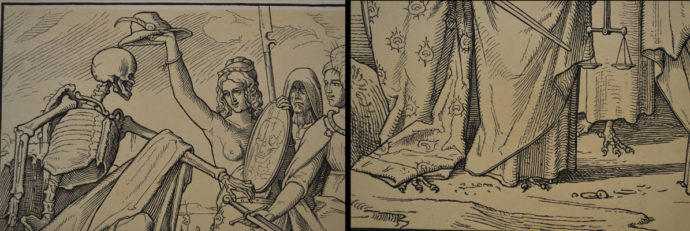

Stone writes that the women may appear to reference the Liberty, Equality and Fraternity of the French Revolution but “closer investigation reveals that the five women have clawed feet and that really, they are the allegorical harpies, also known as furies or vices.” Death, who is fresh out of the grave, is handed a feathered hat by Vanity, who also hold up a mirror. The hat was a well-known attribute of Friedrich Hecker, who, Stone said, “was the leader of the Baden uprising in April, 1848.” Boime wrote: “Hecker was hardly the fanatical rebel they made him out to be. He and his colleague Struve refused to admit workers and peasants to their councils…. Once in the field, Hecker hesitated to fire on government troops and it was their commander who finally ordered the attack on Hecker’s ragtag band and easily crushed them. Hecker escaped to the United States and settled on a farm in Illinois. He was a fervent supporter of Lincoln and spoke out against slavery, distinguishing himself during the Civil War when he rose to colonel in the Union Army.”

As to the other harpies Stone wrote: “The central woman, Cunning, is handing Death the sword of Justice…. the masked Dishonesty holds the scales of Justice and points to the latter’s allegorical figure who, robbed of these attributes, is held bound and captive in the background. Bloodthirst holds a scythe ready for Death, as Madness leads her horse toward him. This horse will accompany Death through the series. Madness bears the 18th-century style coat and riding boots that Death will wear, a reference to the French Revolution of 1789.

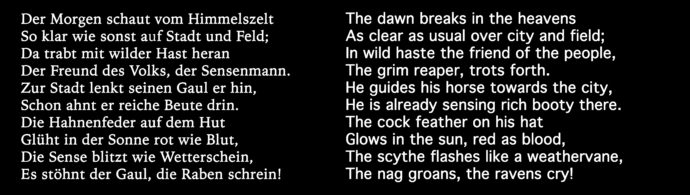

PLATE 2: Der Tod reitet zur Stadt (Death Rides into Town)

Engraved by Richard Julius Jungtow (German, 1828-after 1876) Note that Jungtow was also the wood engraver of Rethel’s “Death as a Friend” 1851 stand-alone print.

Reading Plate 2

Stone wrote: “The second plate shows Death, with his attributes, riding the horse of Madness towards a town, presumably Dresden. Two girls are fleeing before him—the first clue that unlike the Renaissance figure, Rethel’s Death is visible to mortal humans. Also in variance, Rethel’s Death requires magical props in order to seduce his victims, whereas in Renaissance depictions Death was powerful enough to merely place a hand upon his selected.”

Three wood engraved plates from Francis Douce, “The Dance of Death,” William Pickering, London, 1831. From left: The Judge, The Old Woman, The Magistrate. Each 2 1/2″ x 1 7/8″

Stone assertion that in Renaissance images Death was not visible to humans made me consult several Dances of Death in my library. Hans Holbein (German, 1497–1543) is ofter credited with popularizing (if not inventing) a sequence of woodcuts in 1538 that show skeletal Death leading away every member of society from the highness (the Pope) to the lowest (the Waggoner). Only the Begger is left to his own meager devices. The Pickering edition, Douce wrote, offered “a set of fac-similes of the above-mentioned [Holbein’s] elegant designs, and which … have been executed with consummate skill and fidelity by Messrs. Bonner and Byfield, two of our best artists in the line of wood engraving.” In every plate except the Begger’s, Death is present but–indeed–goes unnoticed. “In these designs,” Douce wrote, “…which have the most interesting set of characters, among whom the skeletonized Death, with all the animation of a living person, forms the most important personage; sometimes amusingly ludicrous, occasionally mischievous, but always busy and characteristically occupied.”

Boime wrote: “Rethel’s model was the late medieval allegory of the Dance of Death, most notably the pessimistic episodes by Hans Holbein…. In Rethel’s cycle, Death emerges from the tomb and with calculated vengeance claims the living. He is not the capricious sportsman of the Holbein series, but a scheming politico who destroys those foolish enough to fall for his devious scheme.”

“The second plate shows,” Boime wrote, “Death riding toward an ancient town undergoing the growth pangs of industrial transformation. He enters the open space at a steeply inclined angle reminiscent of a line of sight, zeroing in on his target with his scythe slung over his shoulder. Above the town walls rise the old steeply roofed houses and the spires of a Gothic cathedral, now being crowded by factory chimneys.”

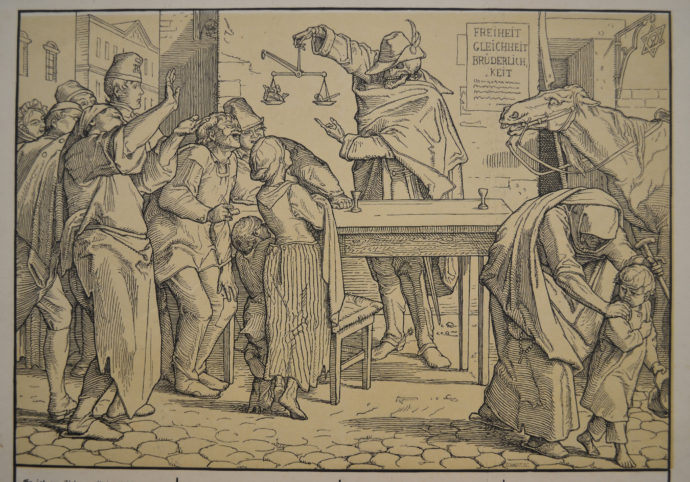

Plate 3: Der Tod vor der Schenke (Death in front of the Tavern)

Reading plate 3

Boime wrote: “Once in the town Death begins work on his deception. Before the door to a tavern filled to capacity, he posts a manifesto calling for Liberty, Equality, and fraternity … and he entertains a crowd with his sly tricks. Shouting “Long Live the Republic,” he holds up the scales of Justice by the tongue instead of the handle, and thus conveys the illusion that the clay pipe of the ordinary citizen weighs as much as a kingly crown.” Stone wrote: “Only the woman at the right, who is blind, and pushing away a small child (perhaps a symbol of innocence), is able to save herself by evading Death’s hypnotism.”

Stone also noticed “the tavern signboard displaying the Star of David…. [This is the very Star of David that repelled me from this series for many years.] Although an emblem associated generally with inns and pubs, it may also convey a coded message to fellow believers. According to tradition, the symbol was used by the followers of the Greek philosopher Pythagoras on their begging tours to notify their comrades that at the place of the sign they would find hospitable reception. Later, the emblem of Pythagorean religious reform assumed both Freemasonic and Jewish connotations. Since Jews were often wine sellers and tavern-keepers in the period, the odds are that Rethel’s positioning of the sign in the tavern scene reinforces rightist accusations of ascendant Freemasonic and Jewish influence on the German uprisings of 1848.”

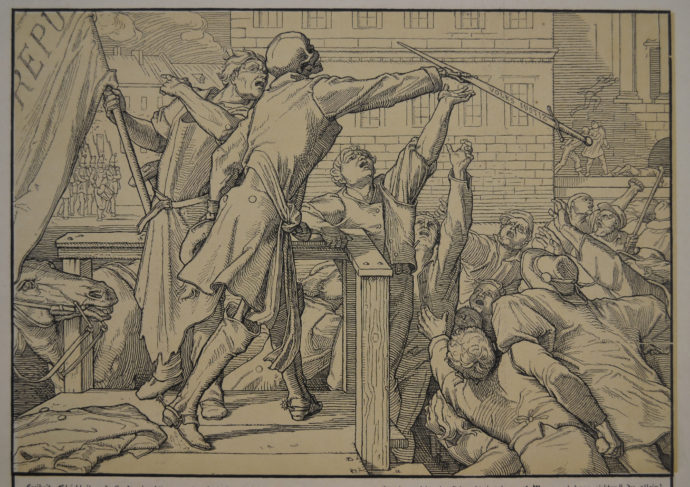

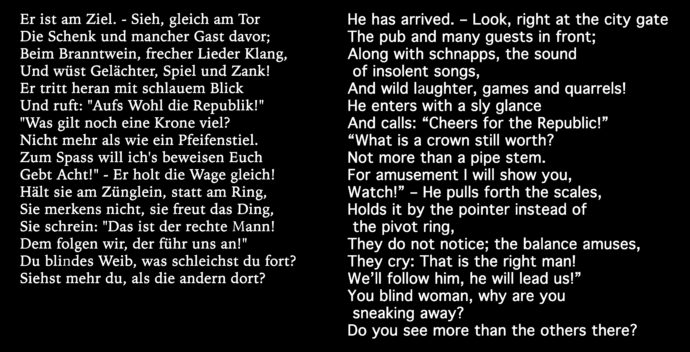

Plate 4: Der Tod übergibt dem Volk das Schwert (Death Delivers the Sword to the People)

Engraved by Gustav Richard Steinbrecher (German, 1828-1887). Note that Steinbrecher was also the wood engraver of Rethel’s “Death as an Enemy” 1851 stand-alone print.

Reading plate 4

In describing Plate 4, Kerrianne Stone said, “Death has his followers totally incited. He stands on a public speaking podium; beside him a blacksmith holds a republican flag. Death hurls his sword which is now marked ‘People’s justice’ into the mob. The deceitfulness of transforming justice’s sword into the people’s sword is another of Death’s acts of illusion.”

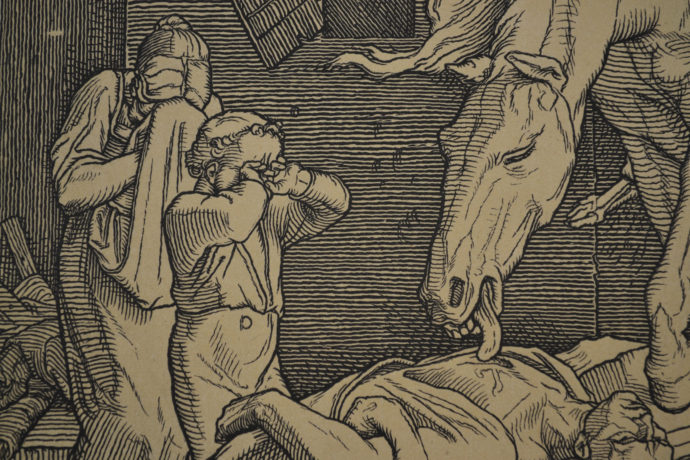

Plate 5: Der Tod auf der Barrikade (Death on the Barricade)

Reading Plate 5

Boime wrote: “Rethel’s next plate depicts to suits of Death’s machinations. People are fighting and dying on a barricade constructed of crates, loose lumber, and barrels filled with paving stones…. Cold horror seizes them [note the face in profile on the far left edge] as they watch him lift this coat to reveal his skeletal nature.” Or as Stone wrote: “Nonchalantly, Death stands with a bloodied flag on the mattress on top of the barricade, and reveals his frightening body to his chosen.” she added: “Plate 5 bears perhaps the strongest resemblance to a graphic novel, with its dynamic and exaggerated action. The comic-strip quality of the series may explain its accessibility and popularity in 1849.”

Plate 6: Der Tod als Sieger (Death as Victor)

Reading plate 6

Stone wrote: “His mission complete, Death in Plate 6 has removed his costume and the attributes provided by the harpies; only the horse of Madness remains. Wearing a wreath of victory, he rides over the remains of the barricade strewn with the dead. A dying man on the right wears an expression of abject horror as the illusion is revealed.” Boime commented: “A dying man is modeled perversely after a figure in Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (whose death is vindicated by the goddess’s appearance): he raises himself up with his last breath only to glimpse the horror of his deception.”

Stone also wrote: “The town is now in ruin, the sword of Justice is discarded on the barricade, and the horse of Madness has its tongue dangling, either from exhaustion or to lap up the blood of a corpse. This final plate is the most famous from the series, one scholar [Peter Paret] describing its emanating horror and rhetoric as unique in European art.”

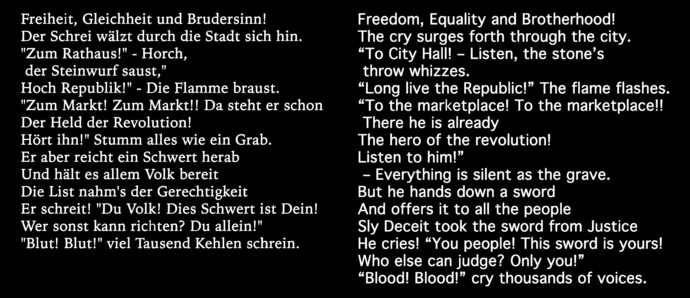

Epilog

Running under Plates 4, 5 and 6 is the following text:

Commentary on Rethel’s designs

“Despite its conspicuous dependence on the medieval broadside tradition,” Albert Boime wrote, “Rethel’s visual conception is strikingly modern in its eccentric and unstable perspectives. The painter’s experience with fresco [he interrupted his fresco cycle on the career of Charlemagne for the council house of his native city of Aachen for his Todtentanz images] enabled him to develop his narrative in effective rhythmic sequence, unfolding in a vivid space immediately addressing the spectator and pungently bringing home every point. Each plate in the series is organized along sharp diagonal movement that commands the spectator’s gaze and keeps the action moving in a fast pace. In plate 3, where Death entertains the crowd, Rethel sets his protagonist in the middle ground and organizes the audience in a semicircular movement that opens up in the foreground to evoke the space of the actual beholder. In plate 4 Death holds forth on a platform that opens out to the spectator’s space at the left, and in plate 5 we are brought smack up against the danger and violence of the barricades with such vivid details as the mattress on which Death stands and the barrel crammed with paving stones. The final plate confronts us with the corpses … pushed against the picture plane, with Death now moving toward the beholder. Rethel clearly orchestrated his compositions to unite his readers with the crowd taken in by the wily manipulator and to make them feel the devastating effects of this manipulation.”

The Context

William Vaughn began in his essay “Death and the Worker: Rethel in 1849” (a chapter in the book Work and the Image: v. 1: Work, Craft and Labour – Visual Representations in Changing Histories, edited by Valerie Mainz and Griselda Pollock, CRC Press, 2018): “Undoubtedly the most celebrated work of art to emerge from Germany as a result of the uprisings of 1848 was Alfred Rethel’s cycle of wood engravings, Auch ein Todtentanz [the book format]…. Almost as soon as the cycle was published–in May 1849 in Dresden (a city that at the time was experiencing a renewed bout of political unrest)–it became a national and international best-seller. The original publication was published in three editions in as many weeks, and soon afterwards was issued as a special volksausgabe (popular edition) [the broadsheet] of 10,000 copies.”

Kerrianne Stone wrote: “A staggering 15,000 copies [of the broadsheet] were sold that year [1849], demonstrating the set’s influence. The prints were distributed throughout Germany and France and some copies were printed in magazines or specifically to use as propaganda, especially in schools, as they promulgated a strongly counter-revolutionary attitude. This series of short revolutions, whose aims included national unification of the loose collection of German-speaking states, also involved demands from the people for freedom of the press, assembly and arms….

“Rethel’s own political stance in relation to his Dance of Death is somewhat ambiguous. Opinions are divided about his personal views and those presented by his work. He was associated with the conservative centre-right faction of the Frankfurt Assembly, but potentially his political attitude was modified after the final and failed May uprising which was quashed in 1849. Rethel does not seem to have been opposed to this Dresden uprising; he was certainly a supporter of the unification of Germany….”

Vaughn explained that “Dresden was the center of radical agitation” in 1848. He wrote: “While the socialists wished to press further with the demands for radical social change, the liberals planned to proceed through the slow process of parliamentary debate and resolution. The liberals were increasing afraid that the radicals were risking all that had already been achieved through the extreme nature of their demands.” He saids it was in this context that Rethel developed his Todtentanz.

Heinrich Karl Anton Mücke (German), “Portrait of Alfred Rethel, looking up,” graphite, 19th century, sheet 8 1/4 x 5 1/4 in. (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Vaughn also pointed out that Rethel finished his designs by the end of 1848, that “when they emerged from the engraver’s studio in May 1849, the designs encountered a different political situation from the one in which they were conceived. At the time they were conceived there was still hope of winning the workers away from socialists to support the liberal democratic cause.” The series, Vaughn said, were therefore not designed in response to “the second round of uprisings in May 1849 which were savagely suppressed by counter-revolutionary forces.”

Albert Boime, however, wrote: “Indeed, since the first proofs were in Rethel’s workshop at the time of the [May 1849] insurrection, it is possible that he modified them under its impact.”

Boime stressed: “It is necessary to clarify Rethel’s political affiliation…. The artist clearly supported a strong central authority and hierarchical social order, a position that dictated his [Charlemagne] program in the Aachen town hall. The repudiation of the attempt in 1848-49 to build a radical democracy in alliance with the impoverished peasantry and working classes was initially received by him and his fellow conservatives was a positive outcome of the short-lived ‘springtime of the people.’ ”

The primary aspect of Boime’s article was to debate “the terms ‘liberal’ and ‘conservative’ with precision in connection with the artist….” He was responding to an article by Peter Paret: ‘”The German revolution of 1848 and Rethel’s Dance of death,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 17, no. 1, 1986. Referring to Paret among others, Boime wrote: “By classifying Rethel–whom I argue was a conservative and counterrevolutionary–as ‘liberal,’ scholars identifying with a centrist position may be projecting their own politics retroactively.”

Boime wrote that Rethel had misgivings about his Todtentanz: “The popular character of the insurrection revealed itself belatedly to Rethel. After witnessing the suppression of the Dresden uprising in early May 1849, he seemed to have had second thoughts about his unprogressive interpretation of events. He characterized the struggle at the time as a ‘magnificent effort for Germany’s glory, which was defeated by the sword of coldly calculating military force.’ He went on to confess:

‘I observed the rise of this movement with mistrust and expected a Red Republic–Communism with all its consequences. But in fact it was nothing more than the enthusiasm of the people in the best sense of the term for the creation of a great and noble Germany, a mission God entrusted to their hearts and not called forth by the radical prattle of bad newspapers and popular agitators.’

The Discovery

When I went to the Baltimore Museum of Art to photograph the plates from its copy of Alfred Rethel’s Todtentanz sequence, I was assuming the Museum had a copy of the book Auch ein Todtentanz. At first I was surprised that the plates were matted and separated from the book. Yet I went about producing the images of the plates that are presented here. But after photographing them, I decided to photograph the cover and the text that appeared inside the cover. It was then that I realized that what the Museum has was not the book but a cut-up version of the broadsheet.

At left is the cover of the book as offered by a book dealer on AbeBooks.com. At right the the cover of the BMA’s Todtentanz. It clearly has the name and typography of the broadsheet with the lines giving credit to Rethel and poet Robert Reinick. And clearly the type was pasted onto the cover in pieces.

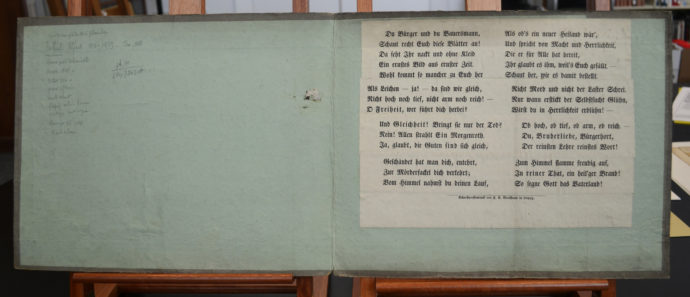

Opening up the BMA’s “book” is text that appears on the broadsheet. The top pair of five lines were originally between the words of the title. Below those are three sets of three lines that formed the epilog, originally below plates 4, 5 and 6.

Ironically, in my attempt not to duplicate the BMA’s Rethel, I end up with another copy of Ein Todtentanz aus dem Jahre 1848 but in its original condition … and in need of conservation.

Sometime Later

Once the paper conservator finishes work on my copy of Ein Todtentanz aus dem Jahre 1848, I’ll post how that process went. While I was told that the work could be done by September or October, the contract I signed estimated time of completion as Jan. 30, 2020.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/rethels-death-as-counterrevolutionary-meme/trackback/

Pingback: Goethe & Graf: Totentanz

Pingback: Schatz’s “Der Ackermann und der Tod” woodcuts