Print Collecting: How they got here

Introduction

When you don’t have deep pockets, collecting becomes an adventure where chance, patience and a good reference library are prime requisites. This ART I SEE blog post will serve to illustrate this by describing the acquisition of the prints currently hanging in the master bedroom, where the theme is, appropriately, the nude.

In some cases a purchase was straight forward: i.e. I saw a print for the first time, haggled for it and bought it. In other cases, an item I saw on a dealer’s website or saw in person at a fair was way over my budget. Years, sometimes decades later, I found another copy of the print for far less and then bought it. In one case, which I’ll save for last, I traded for a print with prints I had purchased long before I could call myself a collector.

The turning point between being a purchaser of prints and a collector of prints came around 1980. Beforehand I bought–often at a local auction house–a variety of prints from English caricature prints, colored botanicals, Piranesi engravings, lithographs of hanging game and a huge collection of chromolithographs of Egypt. Then at an exhibition of newly acquired Federal Art Project prints at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, I got into conversation with a curator who directed me to the Bethesda Art Gallery run by Betty Duffy. Everything she offered in her one-room gallery was by an American artist working mostly in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s. I was in heaven. Duffy was strict. She gave no discounts. But her selection and knowledge were tremendous.

The bedroom

I chose the bedroom because it was small compared to the parlors that grace the first floor of our mid-19th-century Baltimore townhouse. Thirteen prints currently hang in the bedroom. Here are views of the four walls, starting with the north wall (which the bed is against), then moving clockwise around the room.

The prints

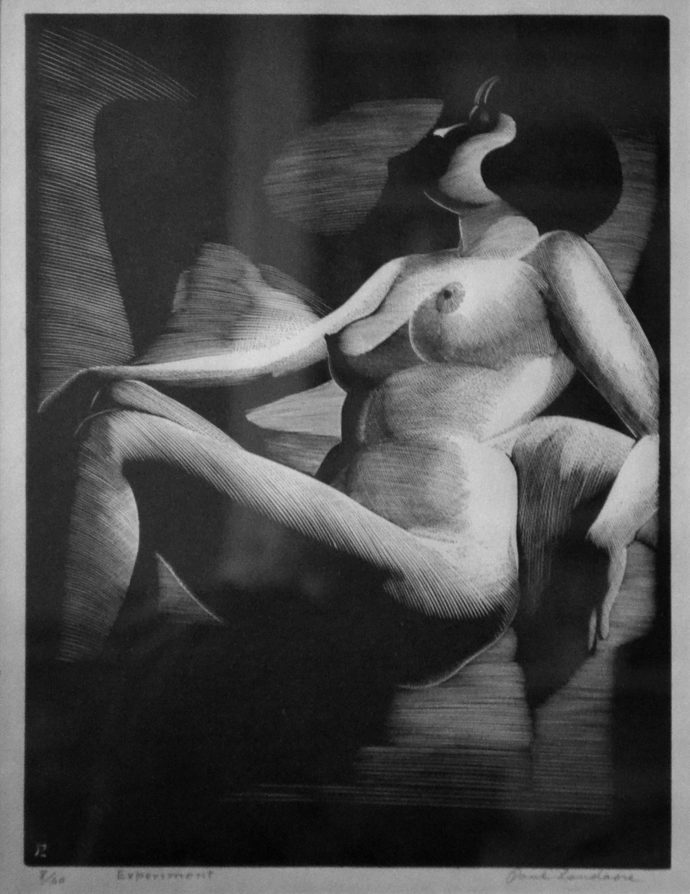

I’ll start with the bedroom’s only print that I bought from Betty Duffy.

This is Experiment, a wood engraving by Paul Landacre (American, 1883-1963). It’s 8″ x 6″ and is marked 8 in an edition of 60. It was purchased at a weekend exhibition in 1989 that Duffy held at the Bethesda Women’s Club. I’ve never seen another copy for sale.

Years after its purchased I found out that Jake M. Wien is working on a catalog raisonné on Landacre. In a July 2016 email he remarked: “Nice early print. I just revised its catalogue entry this morning. The model is Margaret, as you probably know, the artist’s wife.” He also stated at the time: “The book may be published as soon as next Spring. I’m approaching the end of this 30-year marathon.” The book has yet to be published.

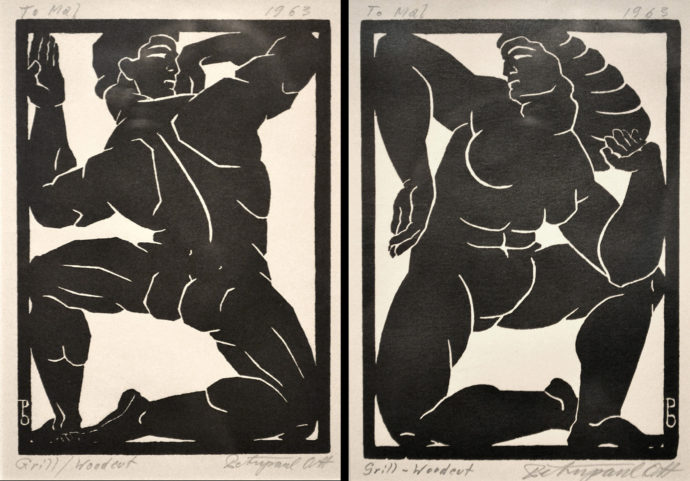

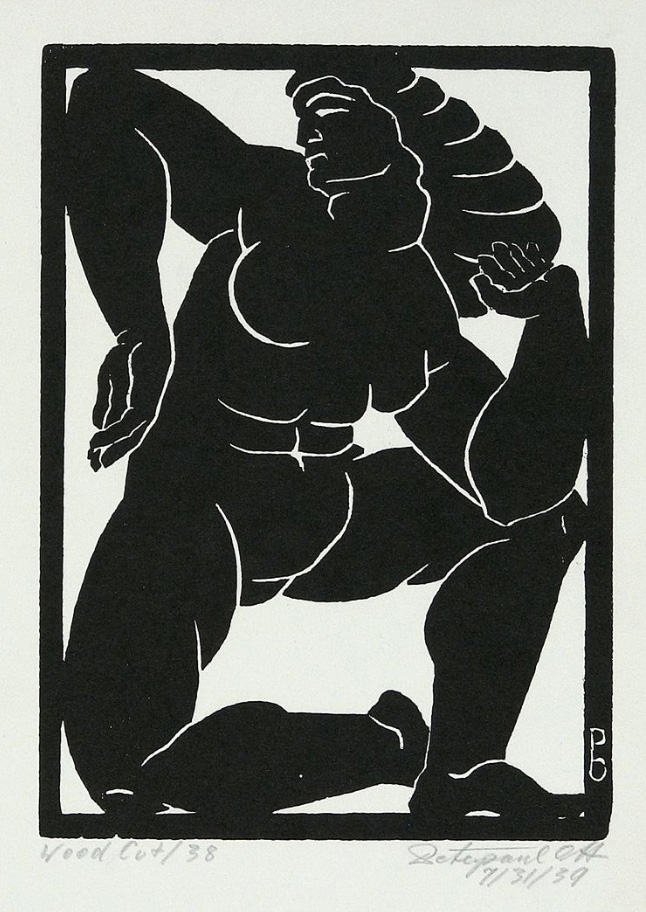

Hanging below the Landacre are a pair of woodcuts–both entitled Grill–by Peterpaul Ott (Czech-American, 1885-1992). While the date above each image reads “1963,” I believe that’s just the date when he made a gift of both prints to “Mal.”

For style reasons alone, they don’t look like art from the 1960s. Better proof is this image of the woman that has been offered on eBay. It’s dated twice. “38” after the woods “Wood Cut,” and “7/31/39” under his signature.

The wpamural.com website has a listing for Ott. It says: “He also worked in a factory carving furniture and received architectural sculpture commissions for the interiors and exteriors of buildings. In 1931, he moved to Chicago where he taught at Northwestern University and the Evanston Academy of Fine Arts. From 1936 to 1939, he was the Chicago WPA supervisor of sculpture. He did the interior and exterior decoration for the Oak Park, Illinois Post Office.”

I suspect Ott titled both woodcuts Grill because he incorporated the designs into a cast-metal grill for one of his architectural projects.

I first came upon the Otts on a dealer’s website, marked about $600 each. I instantly like them, but I wasn’t ready to spring for $1,200. Years later–2008–I bought the pair on eBay for about half the price of one.

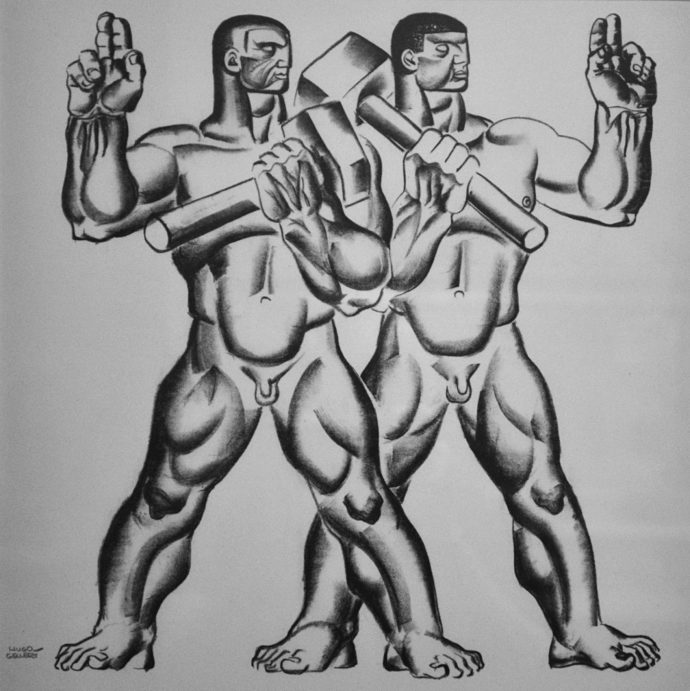

Hugo Gellert’s Primary Accumulation 11, lithograph, 1934, 14 1/4″ x 13″, hangs above the bed’s headboard. Gellert (Hungarian-American, 1892-1985) included the print in his portfolio Karl Marx Capital in Pictures. With 60 lithographs, the portfolio was printed in Paris in 1933 by E. Desjobert. There was also a book version: Karl Marx “Capital” in Lithographs, Ray Long and Richard Smith, New York, 1934.

In November 1997 I had an artist residency at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts in Amherst, VA. During a visit to Charlottesville–some 30 miles to the north–I spotted some framed prints hanging in a used bookstore. The clerk there gave me the phone number of the person selling them. About a week later I visited the home of Alfred Hirshoren and was taken with the prints from the Gellert portfolio. It seemed appropriate once I framed Primary Accumulation 11 up to hang above the bed of Michael, my husband, and me.

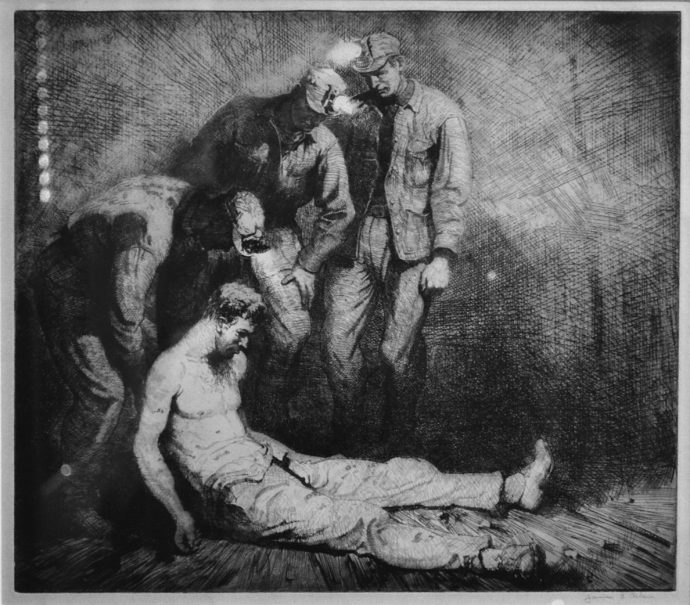

The Accident, a 1934 etching by James Allen (American, 1894-1964), hangs to the left of the bed. I was immediately drawn to this image when it appeared in a catalog that the Mary Ryan Gallery mailed to me in 1988. Allen carefully wiped the plate tone off the injured miner and from the headlamps of his three coworkers. It is as gentle a pieta scene as an artist has ever made. It measures 10 1/2” x 11 15/16” and is from an edition of 10.

Allen is best known for his images of men balancing on naked girders high off the ground (steel monkeys) or workers laying huge pipes. All are heroic images. The Accident is their antipathy–hurt, gentle and caring. I think that was the reasoning behind its pricing, about a sixth of the skyscraper worker etchings. Years later I’ve come across copies of The Accident priced higher than the heroic worker images. I guess I anticipated the market.

Without a doubt this curious wood engraving has the perfect title. Artist C. Marion Mitchell (1899-1985) called her 7″ x 5 1/2″ print Truth Restrained by the Arms of her Lovers. How appropriate for today when “truth” and “fake news” are synonyms.

Without a doubt this curious wood engraving has the perfect title. Artist C. Marion Mitchell (1899-1985) called her 7″ x 5 1/2″ print Truth Restrained by the Arms of her Lovers. How appropriate for today when “truth” and “fake news” are synonyms.

I came upon this print at the 1990 New York print fair on the walls of Abigail Furey’s booth. Usually I can’t afford any print given wall space at a fair. Fortunately, not in this case.

Furey thought Mitchell was British. So I contacted Betty Clark, who ran Studio One Gallery just north of Oxford, England. Clark authored a book on British women wood engravers. She believed that Mitchell was Canadian.

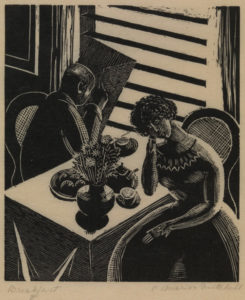

A online search only showed up one other Mitchell print called Breakfast. It’s in the collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. The accessions entry for this print omits Mitchell’s nationality and dates the print only as “1930s.”

One thing consistent is Mitchell’s perspective on a woman’s second-class life.

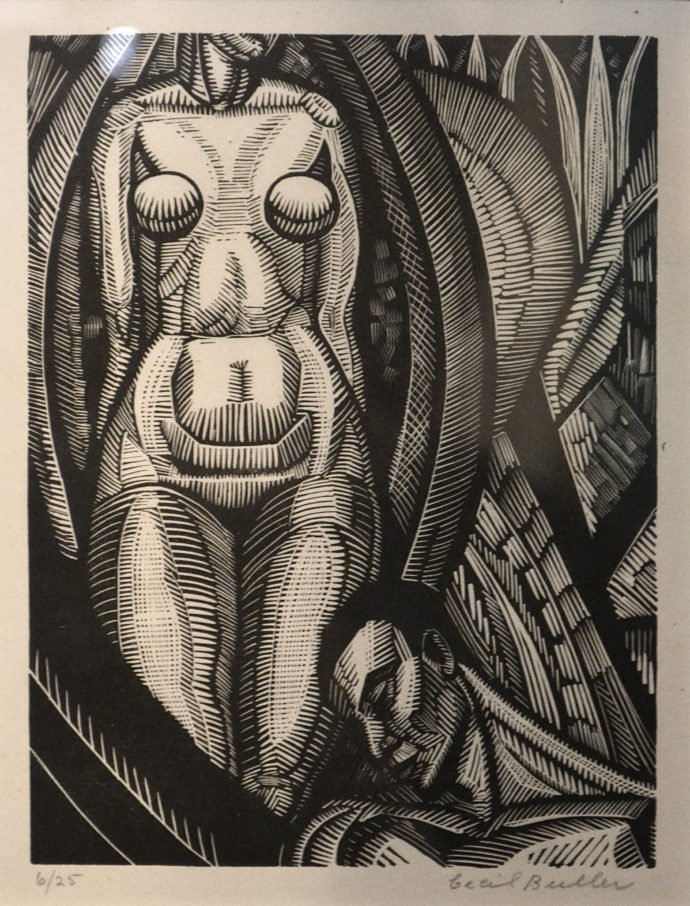

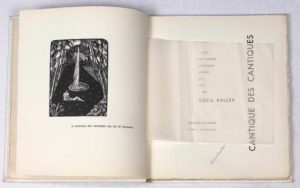

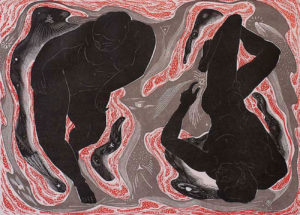

Cecil Tremayne Buller, who made this wood engraving, is definitely Canadian (1886-1973). Patricia Ainslie produced a 1989 catalog raisonné for the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Alberta. This print is from Buller’s 1929 suite of 11 prints called The Song of Solomon, in an edition of 25 by Féquet, Paris.

This image refers to Chapter 7, Verses 6-7. The image is 5 5/8” x 4 1/2”.

In 1931 Buller issued her suite of prints in a portfolio called “Cantique des Cantiques,” Editions du Raison, Paris. I left a bid last September on the whole portfolio but lost out.

I bought my print from Keith Sheridan when he posted it on his website in 2001.

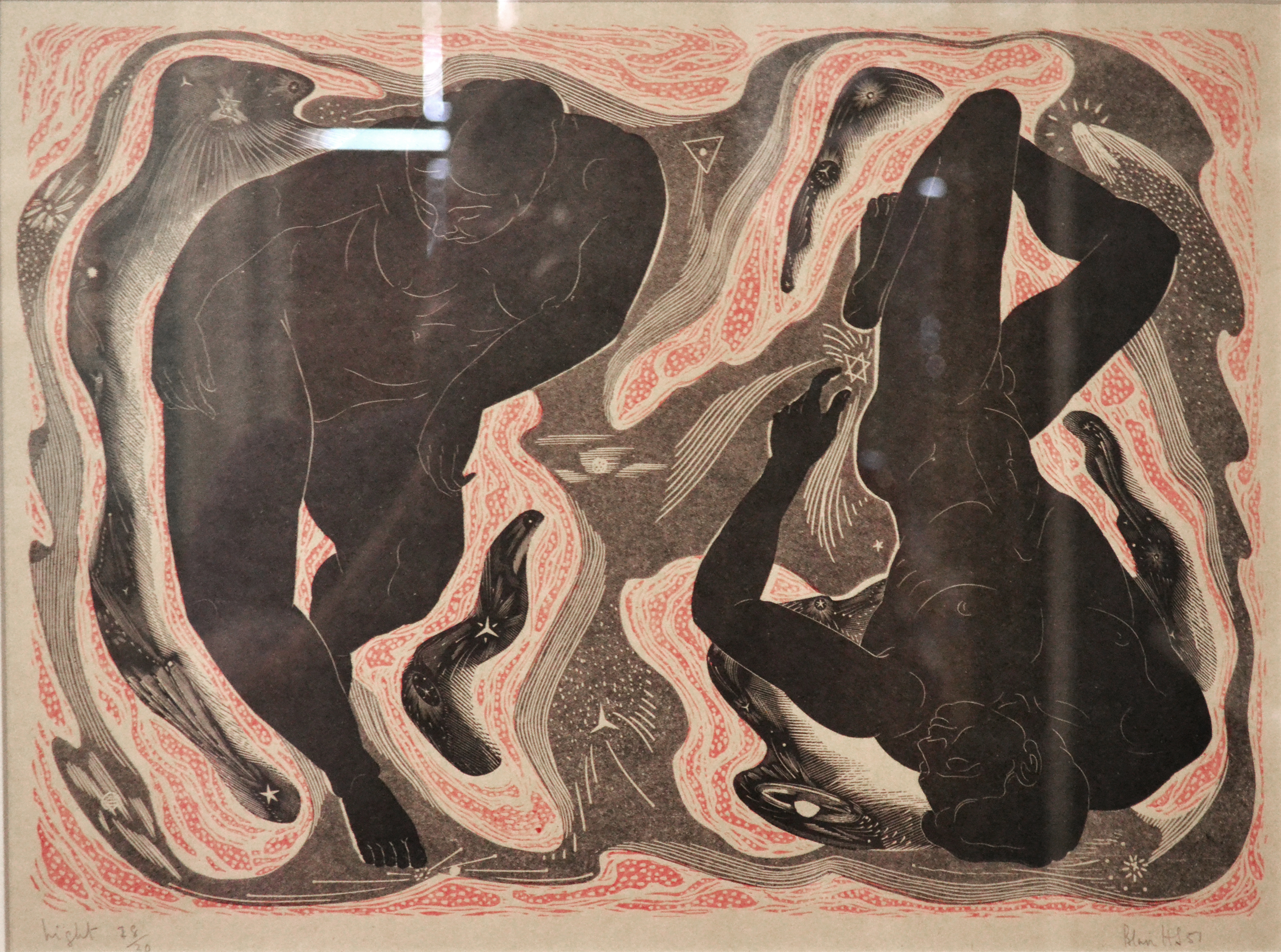

British artist Blair Hughes-Stanton (1902-1991) created Night, a color wood engraving, in 1951 in an edition of 50. It’s 9 1/4” x 12 3/4”. I bought it from Betty Clark in 1982 during my first visit to England.

According to the William Carl Fine Prints website, there was a second “edition of 75 printed for the Portfolio of British Prints published by the UK National Committee for the International Association of Art in 1975.” Carl has sold his copy from the later edition. If the colors of that image on his website are true, then the red was made way too strident in the second edition.

According to the William Carl Fine Prints website, there was a second “edition of 75 printed for the Portfolio of British Prints published by the UK National Committee for the International Association of Art in 1975.” Carl has sold his copy from the later edition. If the colors of that image on his website are true, then the red was made way too strident in the second edition.

I rarely buy color prints, but this one seems more of a black-and-white print with a red block added. I’ve always wondered how many blocks were involved. Three blocks? Two blocks? What do you think?

Once again I apologize that I didn’t photograph this print before it was framed. Once I started a careful inventory of the collection about 10 years ago, I photograph each acquisition soon after its purchase.

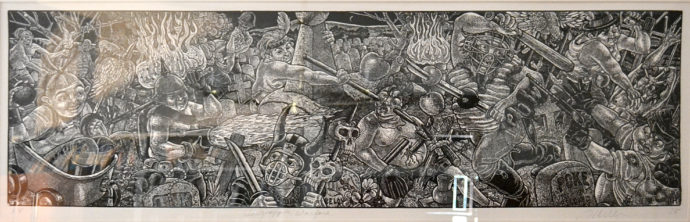

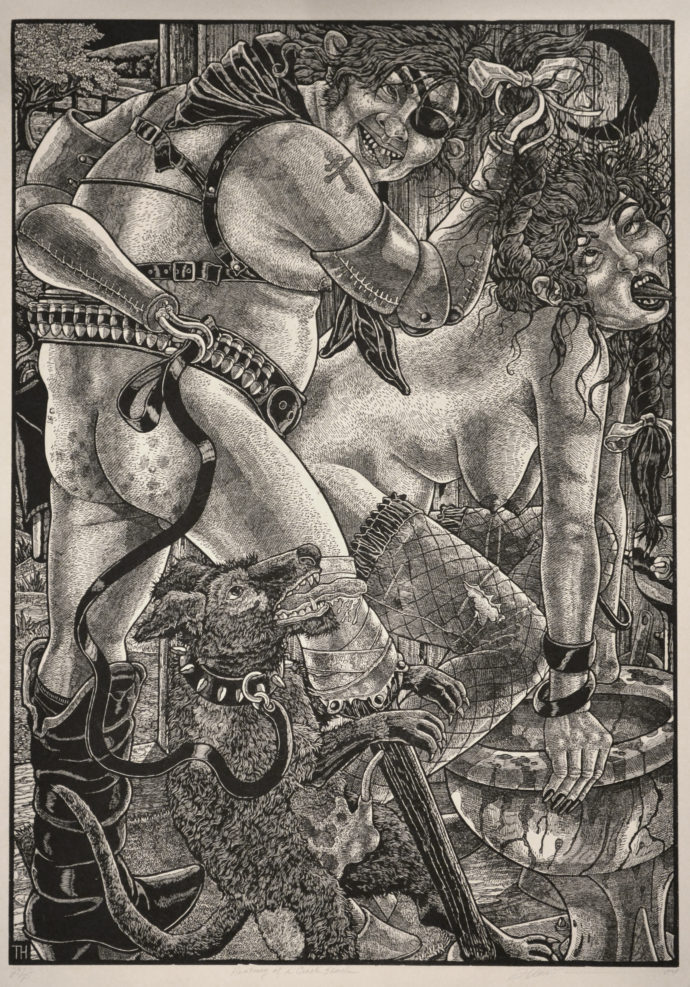

Above is one of Tom Huck’s less gross woodcuts of American mayhem. I purchased Hedgeapple Warfare (2005, AP, 12 1/4” x 40”) on eBay in 2007. It was listed as a fundraising for Space 1026, a Philadelphia non-profit artist collective. Located on two floors of a building at 11th and Arch, Space 1026 calls itself an 18-year experiment and “a community–a creative community–not an institution.”

Above is one of Tom Huck’s less gross woodcuts of American mayhem. I purchased Hedgeapple Warfare (2005, AP, 12 1/4” x 40”) on eBay in 2007. It was listed as a fundraising for Space 1026, a Philadelphia non-profit artist collective. Located on two floors of a building at 11th and Arch, Space 1026 calls itself an 18-year experiment and “a community–a creative community–not an institution.”

Besides being somewhat tamer than Huck’s other woodcuts, it’s also considerably smaller. My other print by this St. Louis artist (born 1951) is Anatomy of a Crack Shack, 2004, 23/25, 52″ x 38″. Again an eBay purchase, but this time from a St. Louis tattoo artist. It hangs in my office, presented unframed and held in place by magnets.

Hedgeapple Warfare, I should say, is the odd man out in the bedroom. It doesn’t fit the nude theme. It just happened to fit nicely above the overmantel mirror. Hmm, now that I write this, maybe Anatomy of a Crack Shack better fits the bedroom theme. But I doubt that I’ll make the switch. Hedgeapple Warfare‘s extreme horizontal format doesn’t work hardly any other place.

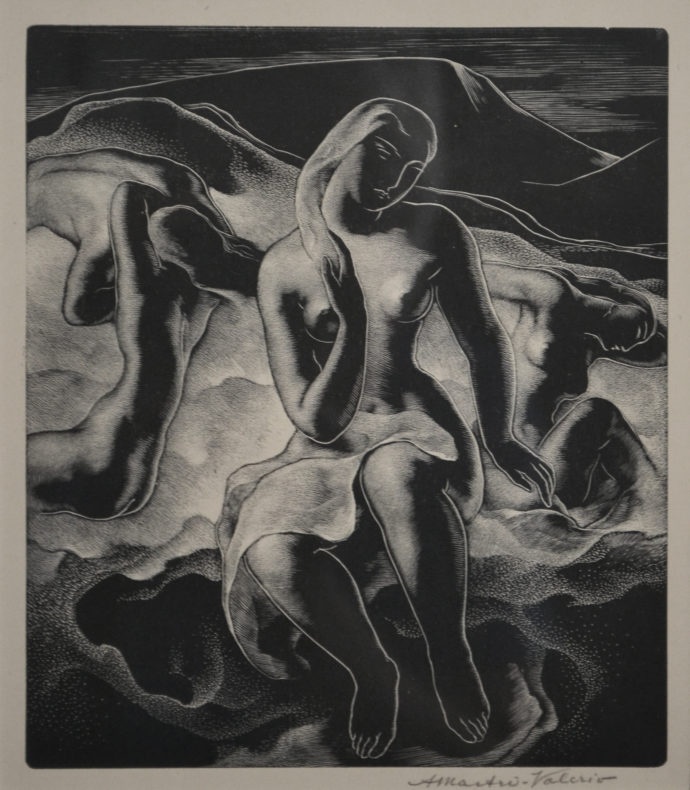

Alessandro Mastro-Valerio (Italian-American, 1887-1933) created the wood engraving Andante, 7” x 6 1/8”, in the 1940s. I was immediately taken by the feathery glow of his highlights when I first saw his work on a visit to the Old Print Shop in Manhattan in 1989. In fact I bought two of his wood engraved nudes then.

Apparently he’s better known for his mezzotints. According the the Keith Sheridan Fine Prints website: “He is best known for his mezzotint prints, particularly his female nudes. His outstanding work helped to revive mezzotint as an artistic medium in the United States.” I guess I’m just a relief-print guy, as you can tell by the bulk of the bedroom prints.

Apparently he’s better known for his mezzotints. According the the Keith Sheridan Fine Prints website: “He is best known for his mezzotint prints, particularly his female nudes. His outstanding work helped to revive mezzotint as an artistic medium in the United States.” I guess I’m just a relief-print guy, as you can tell by the bulk of the bedroom prints.

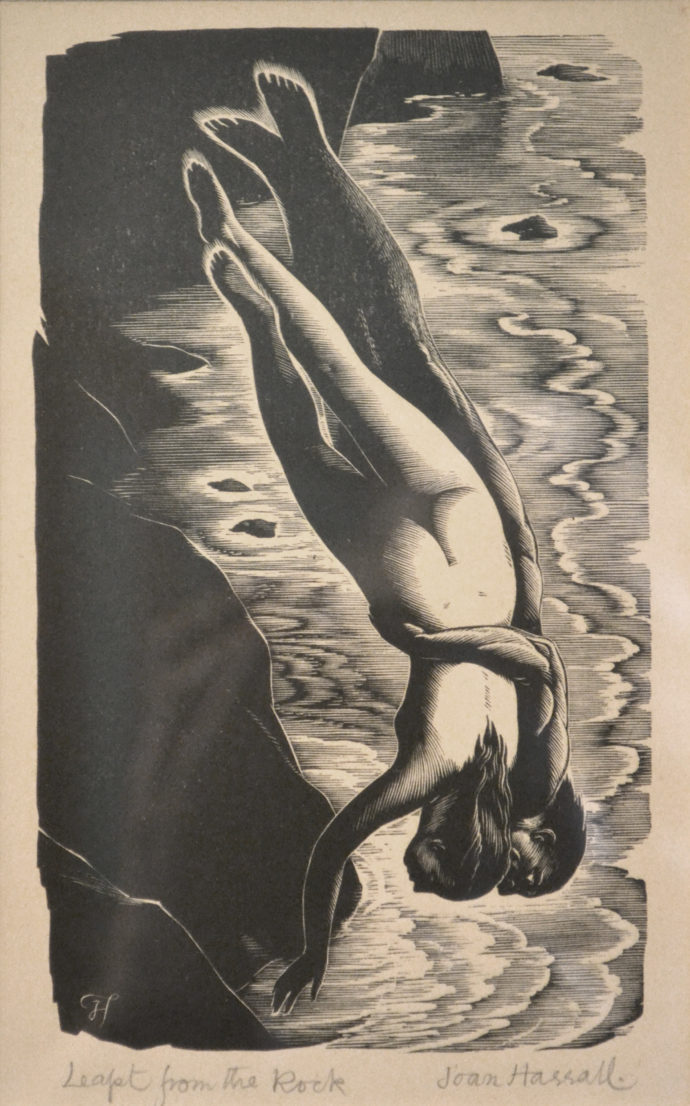

Because of a recent acclaimed movie, I should add that Andante replaced a wood engraving by the British artist Joan Hassall (1906-1988) that I bought in 1985 from Betty Clark in England. It’s called Leapt From The Rock, 5 7/8” x 3 1/2”. Hassall made the image to illustrate the book Sealskin Trousers and Other Stories, Rupert Hart-Davis, London, 1947. The image shows a merman and a nude woman leaping together off a cliff into the sea. Does it not anticipate the finale of the 2017 movie “The Shape of Water”?

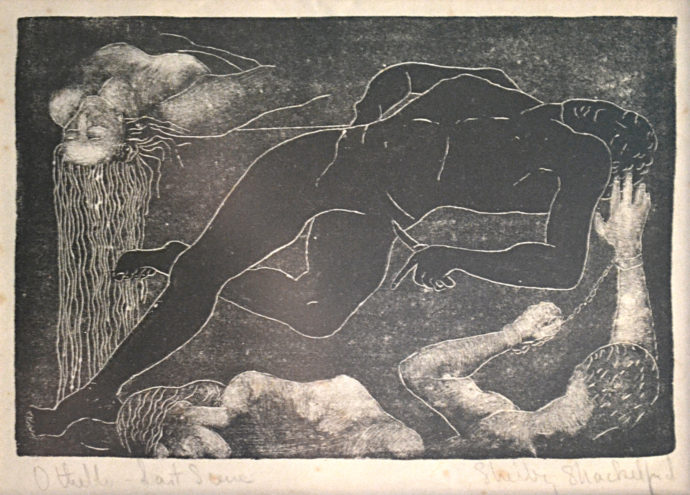

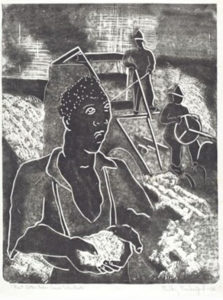

It took some 40 years before I could find a print by Shelby Shackelford (American, 1899–1987). I first came upon her printmaking when I purchased the book “America Today: A book of 100 Prints” (Equinox Cooperative Press, New York, 1936) while in England in 1982. It included her print Rust Cotton Picker Comes to the South. The image shown here is off the National Gallery of Art website. It lists the medium a linocut, but I believe it is an example of her unique wax relief technique.

“America Today” essentially was a catalog for an exhibition held simultaneously in 30 venues across the U.S. in 1936 by the American Artists’ Congress, which was, according to a Wikipedia overview, “an organization founded in February 1936 as part of the popular front of the Communist Party USA as a vehicle for uniting graphic artists in projects helping to combat the spread of fascism.”

“America Today” essentially was a catalog for an exhibition held simultaneously in 30 venues across the U.S. in 1936 by the American Artists’ Congress, which was, according to a Wikipedia overview, “an organization founded in February 1936 as part of the popular front of the Communist Party USA as a vehicle for uniting graphic artists in projects helping to combat the spread of fascism.”

Well, I never came across a copy of Rust Cotton Picker until 2017, when it was priced out of my range. However, in 2013 I spied Othello’s Last Scene, wax relief, 1932, 7 1/2” x 5″, on the website of Harris House Fine Art in Nova Scotia, Canada.

There’s a short bio of Shackelford on a website commemorating the Jefferson Place Gallery (1957-1974) in Washington, DC. Here’s a link. It notes that she studied at Maryland Institute College of Art. She later taught at the Baltimore Museum of Art and served on the museum’s Artists Committee from 1953 to 1960. BMA Director Adelyn Breeskin recommended Shackelford to the Jefferson Place Gallery’s director in 1957.

The Shackelton print Three Nudes appeared in Clare Leighton’s book “Wood-Engraving and Woodcuts,” The Studio, London, 1932. I suspect Shackelford was involved in bringing Leighton in Maryland. In Leighton’s book “Southern Harvest” (The Macmillan Company, New York, 1942) one chapter takes place on a Maryland farm.

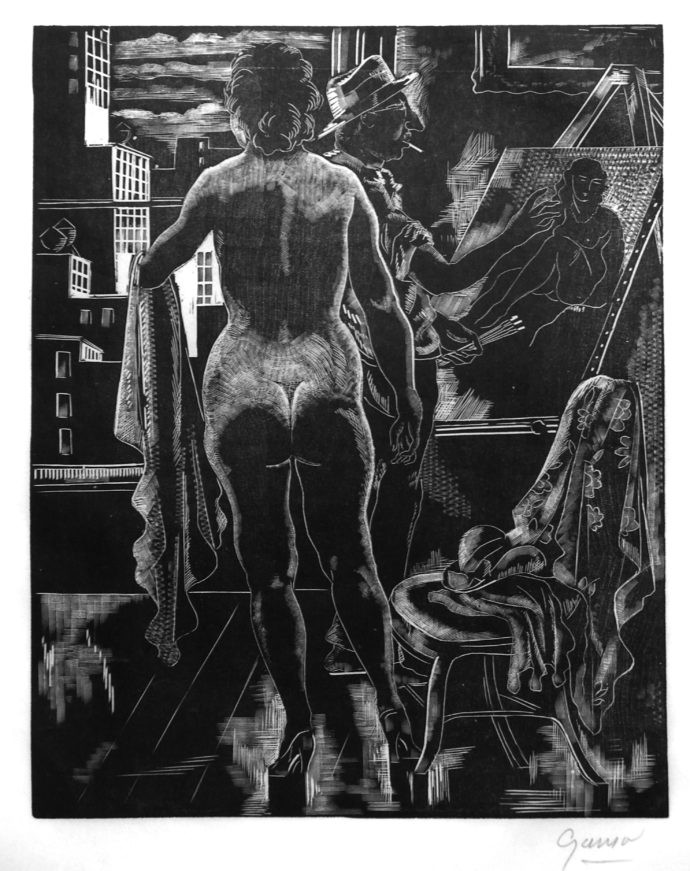

The purchase of Self-Portrait with Nude, a woodcut by Emil Ganso (German-born American, 1895-1941), was also influenced by owning a book–in this case “The Prints of Emil Ganzo,” a catalog raisonné by Donald E. Smith, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997. As I tend to do upon buying a print reference book, I create a wish list. In this case, Self-Portrait with Nude was the one Ganso I really wanted.

I probably bought the book soon after it was published, but I didn’t come across a copy of Self-Portrait with Nude until 2010 when I was visiting New Orleans. While driving on Saint Charles Ave., I noticed a store sign for Halpern’s Furniture. The name Halpern rang a bell. I used to get print catalogs from Herb Halpern. He was also a source for books on printmakers. So I stopped and asked if the store was owned by Herb Halpern. No, I was told, but Herb ran Promenade Fine Fabrics next door.

So I went next door and soon Herb Halpern was pulling down boxes and boxes of prints and drawings from lofty perches. He also brought out portfolios from his crowded office. In short, he had copy of Self-Portrait with Nude, which I purchased.

The Smith book lists this print as a wood engraving, edition of 50 but likely less, 1930, 9 7/8” x 7 7/8”. Ganso’s use of a multiple tool particularly on the model’s torso would lead one to conclude that the print was a wood engraving. Yet, the appearance of wood grain on the model’s back more often happens on woodcuts.

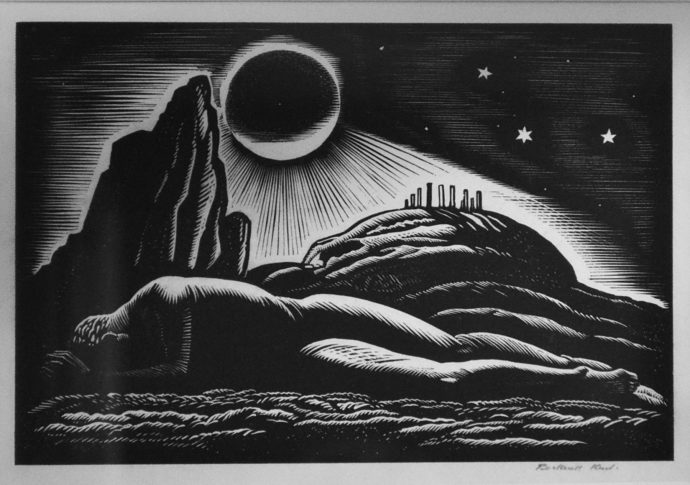

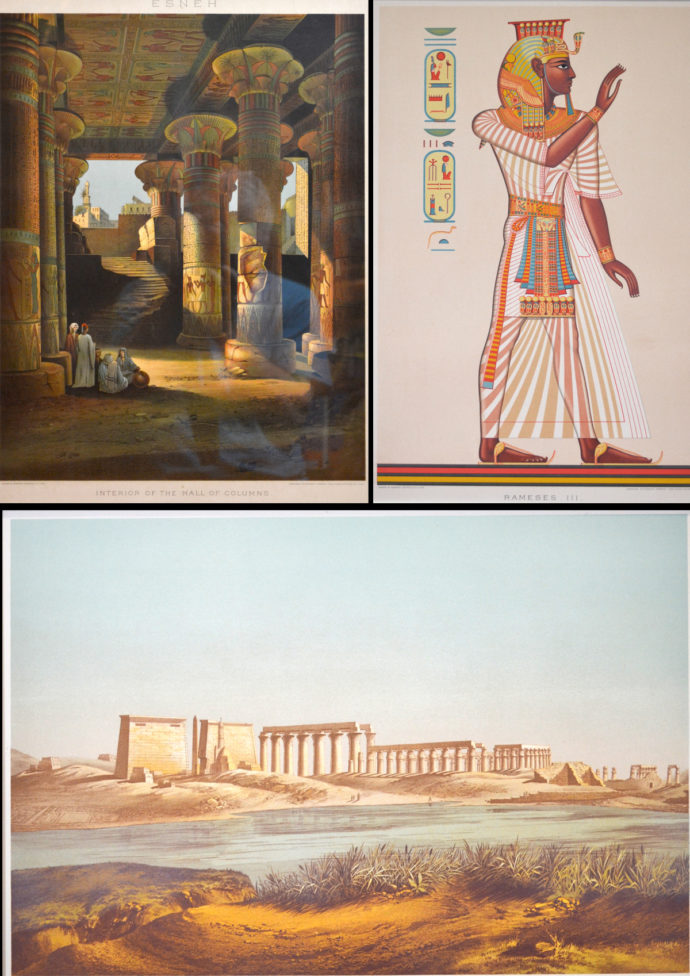

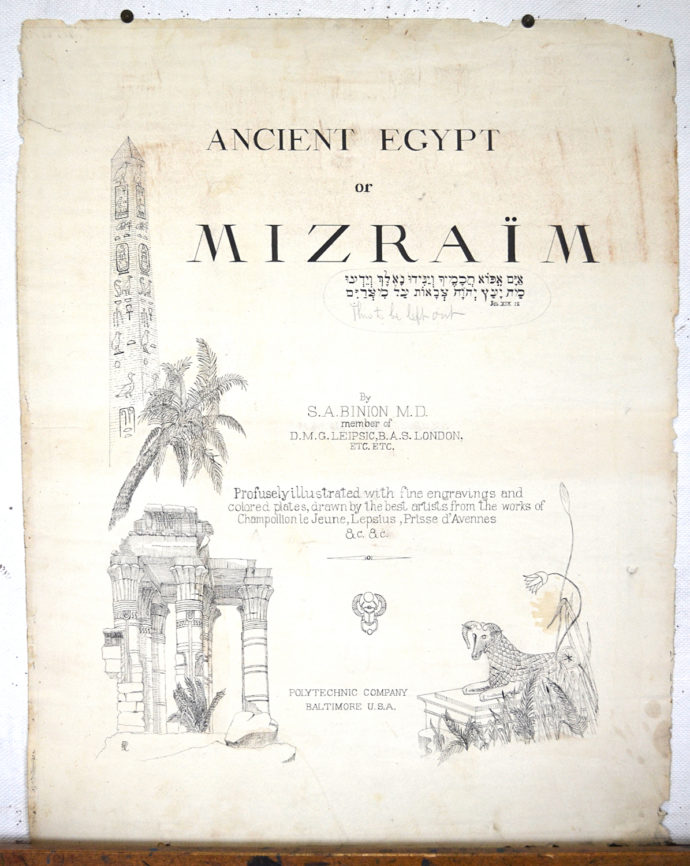

I wouldn’t own a copy of Twilight of Man, a wood engraving, 1926, ed. 120, 5 1/2″ x 7 7/8″, by Rockwell Kent (American, 1882-1971) if I hadn’t bought a proof set of some 100 lithographs for the book Ancient Egypt or Mizraim at auction in the 1970s.

This elephant folio book by Samuel Augustus Binion was initially published in 12 sections by Henry G. Allen & Company, New York, 1887, and subsequently often bound in two volumes. It featured 72 lithographs, many in vivid color.

This elephant folio book by Samuel Augustus Binion was initially published in 12 sections by Henry G. Allen & Company, New York, 1887, and subsequently often bound in two volumes. It featured 72 lithographs, many in vivid color.

What I bought was a proof set of the lithos that was sent to the author–Samuel Augustus Binion, who was an Egyptologist at Johns Hopkins University–from the printer– American Polytechnic Company–in Buffalo, NY. The set had many duplicates. Some had water damaged or were torn. But I had dozens and dozens in great shape. I also obtained a bound, unused salesman’s sample book with pages to add names of subscribers. Additionally, there was a pen-and-ink draft of the title page with penciled notations. Here is reads “Polytechnic Company, Baltimore, U.S.A” but I’m pretty sure the printing was done in Buffalo.

Well, the Craig Flinner Gallery in Baltimore had a copy of Kent’s Twilight of Man. At the time it’s $900 price was more than I had ever paid for a print. But Flinner agreed to a trade. He accepted 27 of the chromolithographs at $30 each in trade for the Kent. Below is a sample of some of the few I kept.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/print-collecting-how-they-got-here/trackback/