Letter from Lynd Ward

TRANSACTION

TRANSACTION

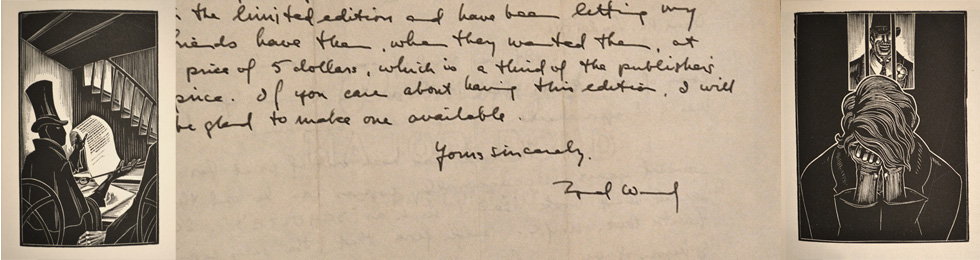

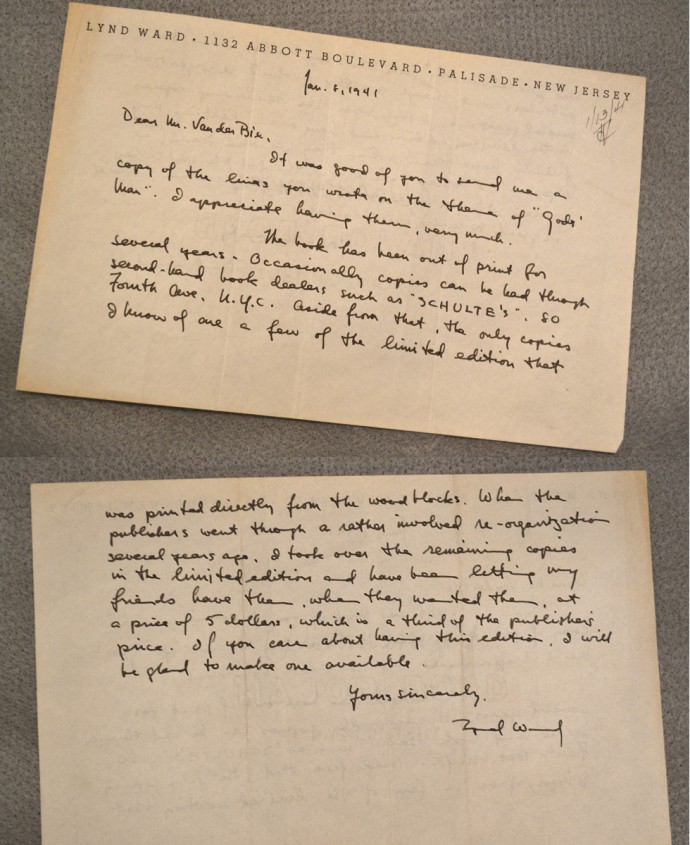

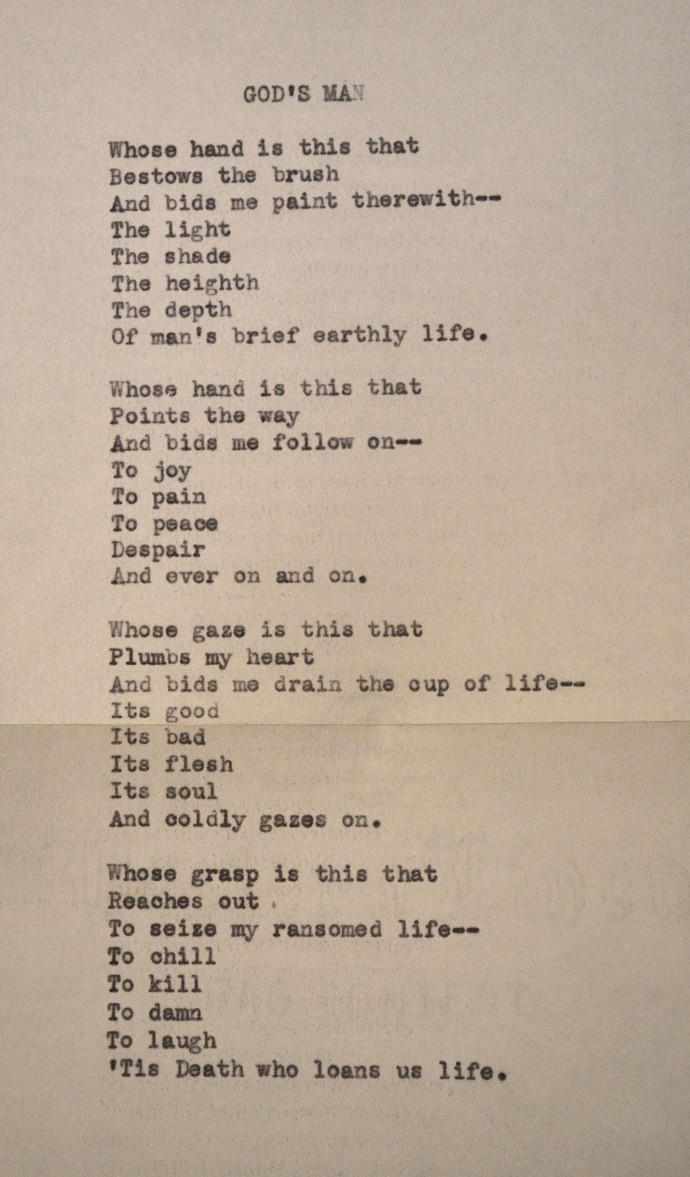

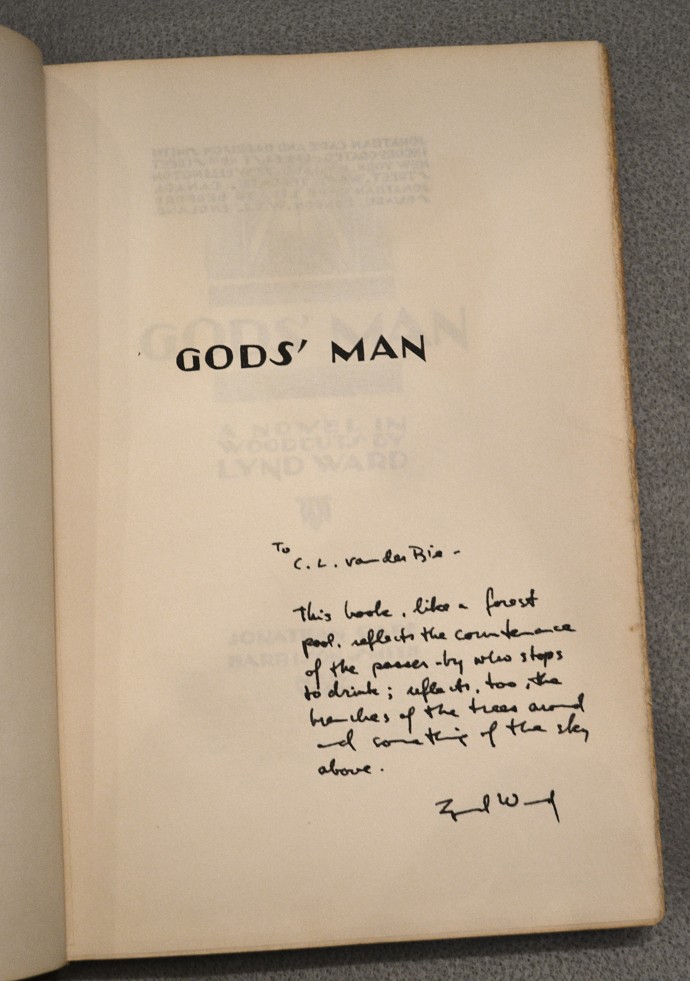

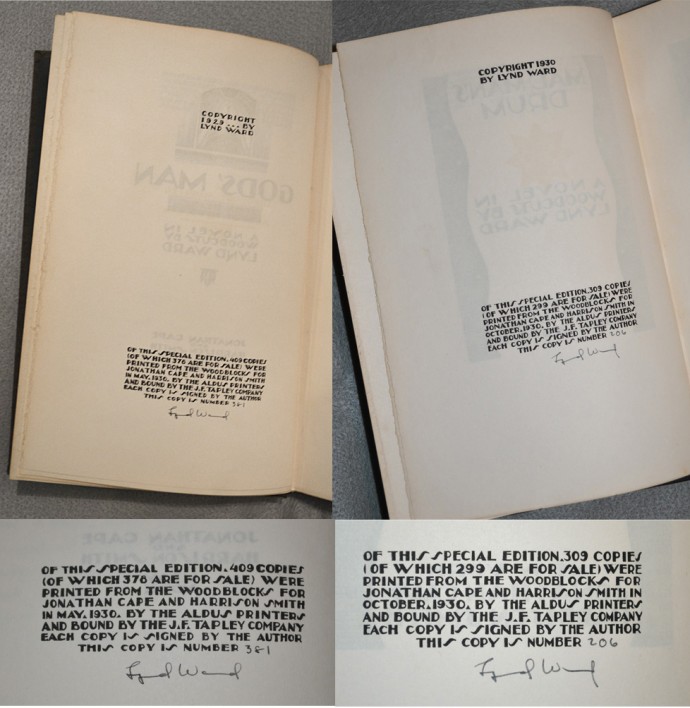

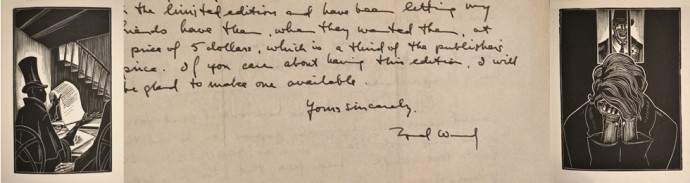

My letter from wordless novelist Lynd Ward (1905-1985) has arrived 74 years late. Then again, had it arrived on time, I wouldn’t have been born yet to receive it. When my letter did arrive this summer, it was tucked into a copy of the limited edition of his first published novel Gods’ Man. On Jan. 8, 1941 Ward wrote to a C. L. van der Bie, who had evidently written to Ward seeking a copy of Gods’ Man, the trade edition of which first came out in October, 1929, within a week of the stock market crash. The following May publishers Jonathan Cape and Harrison Smith, New York, issued a limited edition of 409 copies with impressions pulling directly from the wood blocks. As a way to convince Ward as to the sincerity of his request, van der Bie enclosed a poem entitled “God’s Man” that he apparently wrote. A copy of his poem also was folded into my copy of Gods’ Man. (Note the misplaced apostrophe in the poem’s title. More on that later.) Here’s the letter, front and back on a half sheet of paper:

Jan. 8, 1941

Dear Mr. van der Bie,

It was good of you to send me a copy of the lines you wrote on the theme of “Gods’ Man.” I appreciate having them, very much.

The book has been out of print for several years. Occasionally copies can be had through second-hand book dealers such as “SCHULTE’S,” 80 Fourth Ave., N.Y.C. Aside from that, the only copies I know of are a few of the limited edition that was printed directly from the wood blocks. When the publishers went through a rather involved re-organization several years ago, I took over the remaining copies in the limited edition and have been letting my friends have them, when they wanted them, at a price of 5 dollars, which is a third of the publishers’ price. If you care about having this edition, I will be glad to make one available.

Yours sincerely,

Lynd Ward

Before presenting the poem, I’ll need to put it briefly into context. Gods’ Man is a Faustian tale. In this case a young artist accepts a magical paintbrush from a sinister masked man and signs an agreement. The paintings that result quickly bring him fame, but soon much misfortune and disillusionment. Yet he eventually finds a virtuous woman, has a family, and lives well until the masked man returns to consummate the contract.

Two issues should be to addressed. The first is about the apostrophe. In a letter Ward wrote to Irving Steingart, Nov. 19, 1958, he discusses the book’s title:

And for what it is worth, you may also be interested in knowing that the first title I suggested for the book was “All art is useless.” The name we finally worked out, “Gods’ man,” using as it does the plural, stemmed from the idea that it is usually phrased somewhat along these lines: “the Artist is always the darling of the Gods.”

The above quote appears in Perry Willett’s exhibition catalog The Silent Shout: Frans Masereel, Lynd Ward, and the Novel in Woodcuts, Bloomington: Indiana University Libraries, 1997. Willett goes on to say: “It is fortunate that he did not use his proposed title, for its blatant cynicism does not match the woodcut novel’s themes of artistic integrity and tempting fate. … It is curious that most reviewers, and even many library cataloguers, insisted upon calling it God’s Man, i.e. the singular possessive, even though the title page plainly reads differently.”

The second issue is about poetry. Van der Bie was not the only person inspired by the book to write a poem (if in fact it is his work). The Wikipedia listing for Gods’ Man cites writings by David A. Beronä (Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels, Harry H. Abrams, New York, 2008, and a 2003 article, “Wordless Novels in Woodcuts” in Print Quarterly): “Left-leaning artists and writers admired the book, and Ward frequently received poetry based on it. Poet Allen Ginsberg used imagery from Gods’ Man in his poem Howl (1956), and referred to the images of the city and jail in Ward’s book in the poem’s annotations.”

Willett notes that at one point his publisher was considering matching up Ward’s images with poetry. Willett writes: “A letter from his publisher, Harrison Smith, points to the difficulty Ward had in bringing his vision to fruition, for the publisher originally wished to include poetry within each frame.” Then Willett quotes at letter that Smith wrote to Ward, dated Sept. 6, 1929:

After getting so far off the rails that I was looking for a poet to embellish the wood-cuts with verse, we suddenly came to our senses and realized that a novel in wood-cuts should be exactly that, and that any text whatever took away from the strength of the book.

Smith’s instincts were proved correct. Despite the onset of the Depression, “Gods’ Man,” according to Willett, “sold well–the first edition went through six printings and sold over 12,000 copies through the 1930s, and inspired later editions.”

Ward himself could wax poetic. On the title page of the book Ward sold to van der Bie, Ward wrote:

This book, like a forest pool, reflects the countenance of the passer-by who stops to drink; reflects, too, the branches of the trees around and something of the sky above.

Lynd Ward

AMAZING PRODUCTIVITY

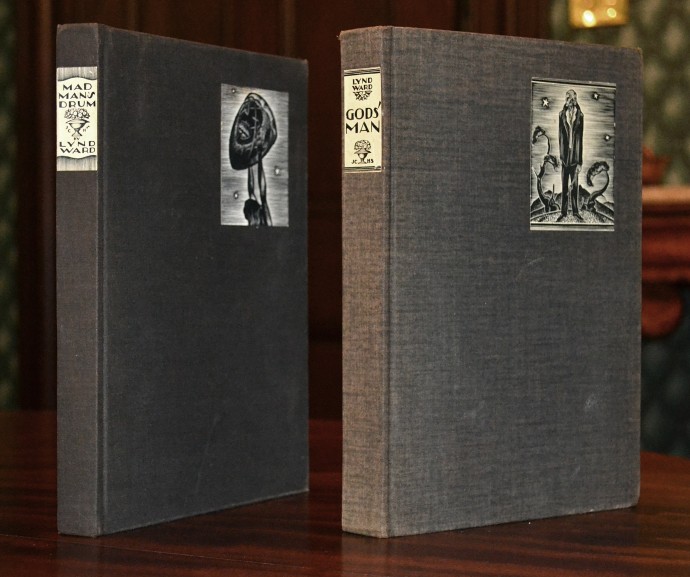

My purchase of the above book completed my assemblage of Lynd Ward’s six wordless novels–both trade and limited editions–plus the 2001 posthumous printing of an unfinished wordless novel. And acquiring Gods’ Man alerted me to how great was Ward’s accomplishment in completing two books in little over two years. In fact the limited editions of Gods’ Man and Madman’s Drum both occurred in 1930. (The trade edition of God’s Man appeared in October, 1929; while the trade edition of Madman’s Drum in 1930.)

I sought out advice from Perry Willett, who’s now Project Manager for Digital Conservation at California Digital Libraries, University of California. I first asked Willett when did Ward start on what became Gods’ Man. Willett replied: “According to an interview published in a journal called Bibliognost (May 1976), he encountered one of Frans Masereel’s woodcut novels when he and his wife were in Leipzig in 1926 or 1927. He says he started working on Gods’ Man in early 1928 after he had returned to NYC.”

Another play on the timing of Ward’s start on Gods’ Man comes from the book’s Wikipedia listing. The online reference site credits Art Spiegelman (Spiegelman, Art (2010). “Chronology”. In Spiegelman, Art. Lynd Ward: Gods’ Man, Madman’s Drum, Wild Pilgrimage. Library of America. pp. 799–821. ISBN 978-1-59853-080-3) in stating: “In 1929, he came across German artist Otto Nückel’s wordless novel Destiny (1926) in New York City. Nückel’s only work in the genre, Destiny told of the life and death of a prostitute in a style inspired by Masereel’s, but with a greater cinematic flow. The work inspired Ward to create a wordless novel of his own.” Wikipedia again cites Spiegelman in saying: “In March 1929 Ward showed the first thirty blocks to Harrison Smith (1888–1971) of the publisher Cape & Smith. Smith offered him a contract and told him the work would be the lead title in the company’s first catalog if Ward could finish it by the summer’s end.” Gods’ Man totals 139 blocks. Did Ward complete over 100 blocks in the next five or six months? Does the “thirty blocks” mentioned in the Spiegelman citation represent all of Ward’s completed plates at that time or just the first 30 of them?

Furthermore, five months after Gods’ Man came out in limited edition Madman’s Drum with its 118 images was published in trade and limited editions by Cape and Smith. How did Ward do it? So I asked Perry Willett is it possible that Wards work on both books overlapped. He replied via email (8/25/15):

I wouldn’t be surprised if Ward was working on both at the same time. It was a fertile period for him, and he was extremely productive. I went through his microfilmed papers from the Archives of American Art: http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/lynd-ward-and-may-mcneer-papers-7159 and was astonished at how many different projects he was working on at any given time as he scrambled to make a name for himself. Plus he seemed to have time to write 4-5 long letters every day. I can’t make any statement about whether he was working on Gods’ Man and Madman’s Drum at the same time—it’s possible there’s something in his papers that would help date their creation.

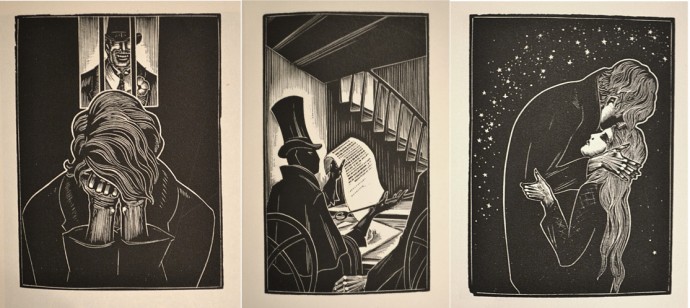

Was there stylistic evidence that separated Madman’s Drum from Gods’ Man? David Beronä in his book Wordless Books says that, “Ward expands his pictorial symbolism in this book [Madman’s Drum] and used more engraving tools to achieve detail in his characters and settings.” In Wikipedia’s Madman’s Drum listing cites an “Introduction” by Art Spiegelman in the 2005 Dover edition of the book: “The art has a variety of line qualities and textures, and more detail than in Gods’ Man. Ward availed himself of a larger variety of engraving tools, such as the multiple-tint tool for making groups of parallel lines, and rounded engraving tools for organic textures.”

(This following paragraph was added 9/3/15 after the author finally purchased a copy of Storyteller Without Words: The Wood Engravings of Lynd Ward, Abrams, New York, 1974.)

In his Storyteller Without Words essay preceding the plates from Madman’s Drum, Ward writes: “In Gods’ Man, except for the use of round and flat gravers to remove white area, all the rendering of figures and landscape had been done with a single line tool. In Madman’s Drum, by contrast, I sought to develop a wider range of tool work and utilized small round gravers to break up a dark area with small jabs of the tool, thus achieving a variety both of tonal effect and textural quality. At the same time, I put more emphasis on decorative patterns in such things as dress material and walls of interiors….”

Willett in his The Silent Shout doesn’t address pictorial style but says: “Ward’s second woodcut novel attempted a more ambitious narrative, less bound to an archetype than Gods’ Man.” Yet Spiegelman (via Wikipedia) believed the “story was bogged down by Ward’s attempt to flesh out the characters and produce a more complicated plot. He [Spiegelman] believed the artwork was a mix of strengths and weaknesses: it had stronger compositions, but the more finely engraved images were “harder to read. …”

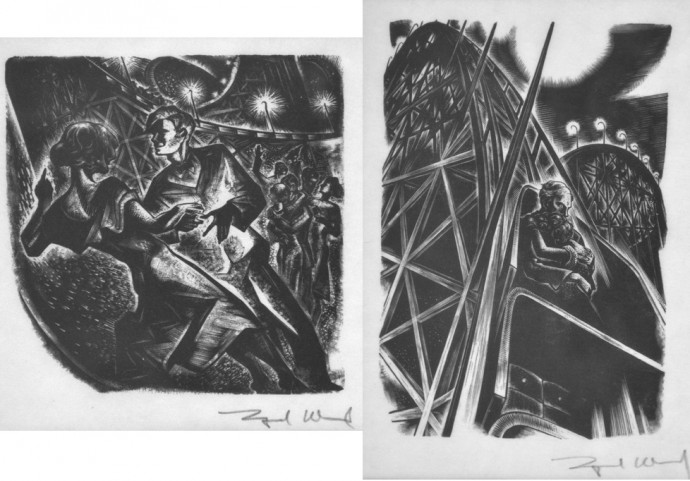

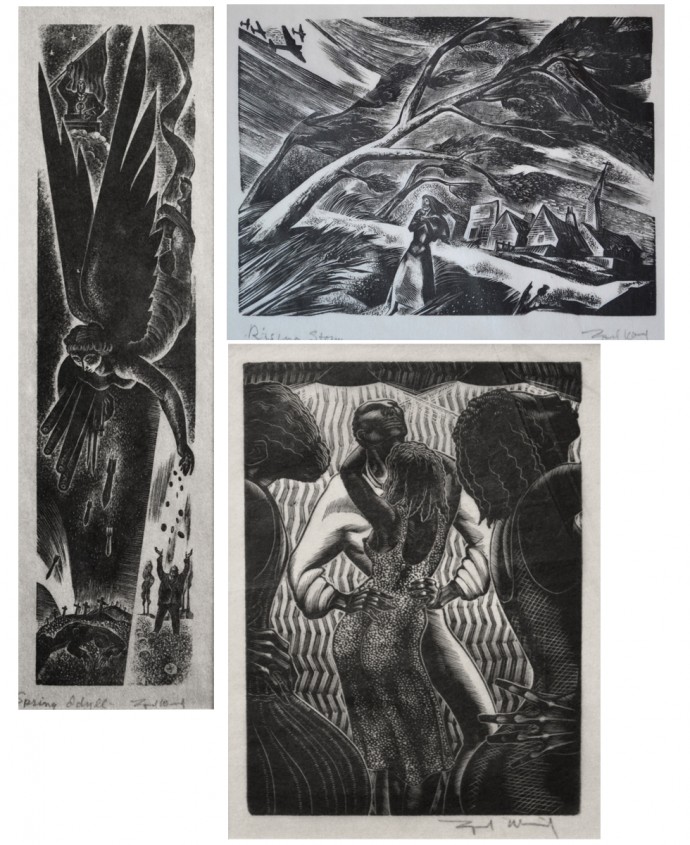

I randomly picked out three images from each book. Can you see a difference in cutting and design?

The top three images are from Gods’ Man, the bottom three from Madman’s Drum.

Finally here are some images of signed Ward wood engravings in my collection.

These two are images were used in his 1937 book Vertigo. (Both were purchased on the same day in 1981 from the Jane Haslem Gallery, Washington, DC.) You can easily see further refinement in his technical skills as a wood engraver. Oddly enough I bought both before I obtained a copy of Vertigo. So I didn’t know where each fitted in the storyline. Yet the difference in tone was palpable: Both take place at an amusement park, with the left image being quite joyful, the right quite desperate. In fact the left image comes very early in the book, when a teenaged couple–fresh from high school graduation–enjoy an evening of frivolity and hope. The right image is the very last image. The couple, separated during most of Vertigo, finally reunite but cling to each other as they stream vertiginously down a roller coaster.

The left (Spring Idyll, 1938) and top right (Rising Storm, 1939) prints were not part of book imagery, rather independent wood engravings. (Both of these were bought from the Bethesda Art Gallery, Bethesda, MD, on the same day as the Vertigo prints were acquired.) Both illustrate how aware Ward was of the imminence and injustice of war. The bottom right print was an illustration to the chapter “La Martinique” in Alex Waugh’s book Hot Countries (Literary Guild, New York, 1930).

The left (Spring Idyll, 1938) and top right (Rising Storm, 1939) prints were not part of book imagery, rather independent wood engravings. (Both of these were bought from the Bethesda Art Gallery, Bethesda, MD, on the same day as the Vertigo prints were acquired.) Both illustrate how aware Ward was of the imminence and injustice of war. The bottom right print was an illustration to the chapter “La Martinique” in Alex Waugh’s book Hot Countries (Literary Guild, New York, 1930).

And the Martinique print is all-but proof that Ward multi-tasked as Willett remarked. The six full plates and many chapter headers in Hot Countries were likely to have been created while he was cutting blocks for Madman’s Drum. I hadn’t realized that until I sought out the book’s publication year.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/letter-from-lynd-ward/trackback/