Leilot: Erich Glas’s Traumatic Creation

Introduction

As often happens these days, it all began with an online search. Not my search, but that of a granddaughter of an artist about whom I had recently written.

Last June I added to my ART I SEE blog with a post on Erich Glas’s c.1920 portfolio of eight wood engravings on Aesop’s fables (Phaedrus Augusti Libertus: Aesopische Fabeln, Amsler & Ruthardt, Berlin). I was quite taken by the intensity of his compositions and the skill of the block cutting. Aside from a brief Wikipedia listing, little information was available about the German-born Israeli Glas ( ערי גלס in Hebrew) (1897-1973). (See my first Glas blog post.)

The Erich Glas portfolio “Aesopische Fabeln.” Each wood engraving was signed and mounted in a folder. (Photo: Scott Ponemone)

In late July I received an email from Hagar Lev, one of Glas’s grandchildren. She was also writing about Glas, and had found a passing reference to him in my post about the American printmaker R.O. Hodgell. “I immediately read the ‘Fables’ blogpost with much excitement,” she wrote, “then contacted you (and dragged Iddo [a cousin]) into the project.”

Thus began an email exchange with Lev and Iddo Gal. Throughout they were generous in sharing images of their grandfather’s art. At first they could give few specifics about Glas’s art, but thanks to the exchange I first learned what a fascinating life Glas led: from his service in the German army during World War I, to his art training at the Bauhaus, to his flight to Palestine for life on a kibbutz, to his assistance to the Zionist underground, and to his three marriages and four sons.

Eventually I received a video from a posthumous retrospective that showed someone leafing through a book of linoleum cuts that presented a dramatic wordless depiction of the Holocaust. I learned that there was not only a marvelous story behind the creation of this book–Leilot (Through the Night in English, לילות in Hebrew)–but also a daunting publication history.

Let me first acquaint you with Hagar Lev and her cousin Iddo Gal and what they could tell me about themselves and their grandfather.

Iddo Gal and Hagar Lev in Stuttgart, where last summer they visited a special Bauhaus exhibition featuring their grandfather’s works. (Photo by Hagar Lev)

Glas and his Grandchildren

Lev is one of Glas’s eight grandchildren. She lives in Germany, the others in Israel. She wrote, “Between all the cousins, we have quite a few works of art from Erich (hundreds). A few years ago we documented part of the collection by ourselves.”

Gal clarified, “Just to add to what Hagar wrote that there is no ‘estate’ as such, i.e., no centralized repository of works that is managed on behalf of the family. Each of the cousins has a share of the collection, which was divided semi-randomly about 40 years ago between his widow and Erich’s four sons, who all passed away. So the works are now distributed among the eight grandchildren.”

Lev shared a link to an online album of her grandfather’s artwork with over a hundred images. It included prints, watercolors, drawings, and oil paintings. I did pick out a few prints–some dated to the 1920s–as well as some images I found elsewhere online and asked Lev: Were they book illustrations or part of another portfolio? But she couldn’t help.

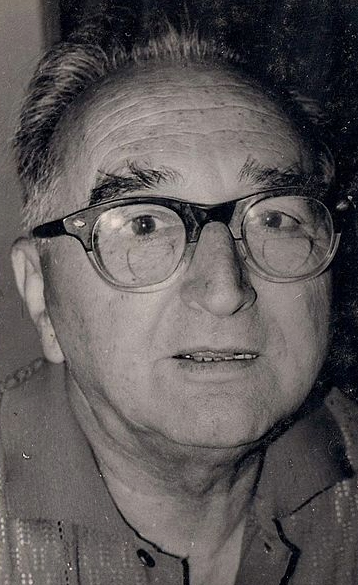

Erich Glas (Courtesy of the Erich Glas Estate)

At that time I also perused auction records and came across two references to Glas’s Leilot portfolio, “depicting the horrors of the Holocaust,” as one auction listing put it. Since the power of the Leilot was not apparent from the few of the plates that were depicted online, I didn’t initially question Lev and Gal about them.

Meanwhile I asked them if they could share remembrances of their grandfather. Gal explained that most of the grandchildren were very young in 1973 when Glas died. Lev wrote, “I have written to all of my cousins and spoke to some of them. As we expected, they do not remember much in terms of conversations with Erich about his art in general. Those were different days. The big age gap and maybe also the German education made Erich a rather distant grandfather. Not in the sense of not showing love, just not one that shares and speaks at length like the grandpas of today.”

Gal added, “The grandchildren were all (except me) age 11 or younger when Erich died in 1973. He was sick most of his last year. Hence, I doubt anybody can have any memories of him painting, from such a young age, and with a 45+ year gap.”

Gal also told me about a retrospective in 1983–ten years after Glas’s death–at the Marc Chagall Artists’ House in Haifa, Israel. “The exhibition,” Gal said, “was self-curated by the family. We did the selection, actual framing (I was involved and Hagar as well, under Yoram [Gal], her father), etc. We have the program booklet in Hebrew.”

Hagar Lev kindly translated the Hebrew text her father wrote for that exhibition, which also included a biography of the artist. Gal and Lev contributed more details on Glas’s three marriages.

Erich Glas’s German Years: 1897-1933

Yoram Gal’s account sheds important light on the events–unavailable online–that shaped Glas’s life:

Erich was born in Germany in 1897. His mother was an actress/theater souffleuse [prompter] and they wandered with theaters from city to city. He never knew his father. When he was 6, his mother had an on-stage accident, suffered severe head-injury and became disabled. Since then his uncle and aunt, who were famous personas in the German theater world…had provided for him…. His plans [to become an engineer] were interrupted at the outbreak of the First World War. He was recruited and served for the entire duration of the war. Having joined when little more than a boy, he came home with the Iron Cross of the First Class, gained on the Western Front, for gallantry as a pilot.

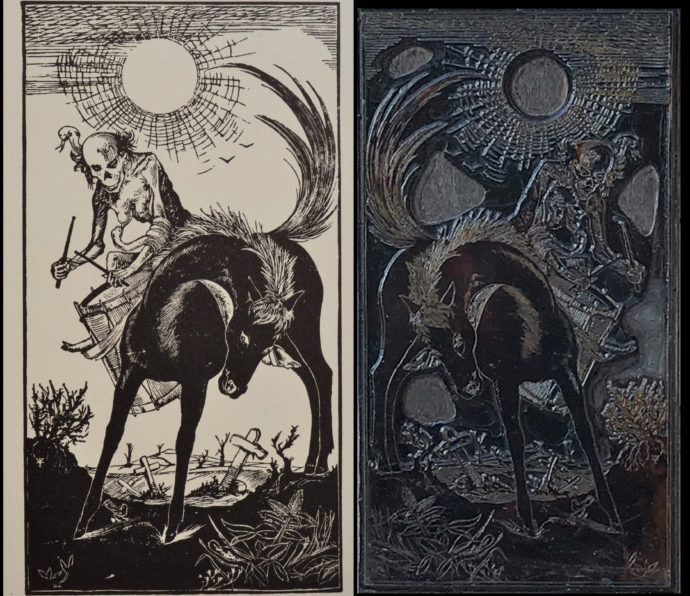

(left) Erich Glas, “The Devil Rides in Flandria” (Flanders), 1924, relief print, 24.5 x 30cm and (right) the block for the print. © 1942-2018 Erich Glas Estate

While at the front, he began painting the horrors of war, and consequently he changed his plans and went to study art. As a young painter, he aspired to the level of the medieval German masters. During his studies in Munich and at the Bauhaus (in its original Weimar residence), he concentrated his efforts on etching and lithography….

Erich’s works in the 1920s were influenced by his closeness to a group of artists who were identified with innovative trends in German art. In particular, one can mention his connections with Alfred Kubin, the well-known German surrealist who greatly influenced his work at the time. But surrealism was not really Erich Glas’s style, and from this point on he adopted the approach that characterized his work and his relation to art in the years to come: He wanted to document reality without associating himself to any contemporary trend. He saw himself as an artist depicting what his eyes see, of reality…. His inclination to use complex techniques to depict reality grew stronger when he studied with Max Liebermann in the early 1930s.

Erich Glas believed that a painter must be familiar with the subjects of his paintings…. When he was preparing to make a series of paintings of the mentally ill, he had obtained permission to live in the mental hospital and had wandered in the corridors for two weeks, dressed in a doctor’s robe….

Lev said that Glas’s first marriage, to Hamburg native Miele-Maria Zacharias, “did not turn out well, and they separated after 2-3 years. I am not sure we know why. We have to bear in mind they met very young, maybe they just weren’t right for each other. After their separation he moved to Berlin (1925).”

Erich and Maria had a son, Gotthard. Lev said, “When the Nazis came to power in 1933, [Gotthard] moved (with his entire school) to the United Kingdom. He arrived to Kibbutz Yagur [southwest of Haifa in what is now northern Israel], where his father was in 1936 and changed his name to Uziel Gal.” Uzi (as he was called) was the designer of the submachine gun that bears his name.

In his text Yoram Gal states, “A few months after the Nazis had risen to power, Glas realized he had to leave Germany.” In 1934 Glas emigrated to Eretz Israel (the British Mandate of Palestine).

Erich Glas’s sons: (top) Reuven, (from left) Yoram, Michael and Uziel. (Courtesy of the Erich Glas Estate)

“Shoshana (Susi) Adler was his second wife,” Lev said. “She was born in Munich in 1907. They first met in her house. Suzi was the daughter of Karl Adler, whom Erich had met in the army…. Erich and Shoshana married in 1929…. They both arrived in Palestine in 1934, together with Michael, who was a less than 2 years old.” They had two more sons, Yoram (in 1936) and Reuven (in 1944). “All are deceased by now. Reuven was killed in the 1973 war.”

Kibbutz Yagur: 1934-1957

Yoram Gal’s account written for his father’s 1983 retrospective continues onto the next stage of Glas’s life.

Arriving in Kibbutz Yagur in 1934, Erich met a completely different form of life than he knew. From an urban lifestyle, in the culturally rich salons of his native Germany, from the artists’ circles of Munich and Berlin, he was quickly moved with his family to an agricultural settlement struggling for its existence. It was hard for him to adapt to the language, the mentality, the kibbutz life, and the standard of living that prevailed in these days.

He was required to reconcile his desire to continue to engage in art with the needs of the kibbutz. Thus, he found himself using old skills he had acquired in Germany: He worked as carpenter and art teacher at the school, participated in the kibbutz patrol organization, prepared sets and props for celebrations and plays, decorated calendars and pamphlets.

Erich’s famous urge to document reality and events at the time and place they took place and in real time quickly brought about the attempt to create a rich and comprehensive picture of kibbutz life…. At first, he photographed and later on also filmed everything he saw—parties and ceremonies, people at work, landscapes and moments in the development of the kibbutz….

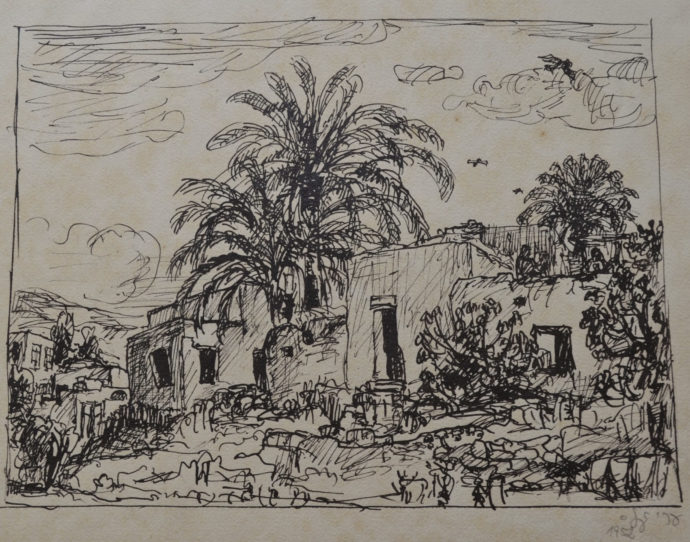

Erich Glas, pen-and-ink drawing, dated 1952 © 1942-2018 Erich Glas Estate

The Haganah [Zionist underground] took advantage of his qualifications as a pilot and photographer—a rare combination in the days prior to the establishment of the State—for aerial and intelligence photography. On one occasion he took one of his sons as a cover for a “photographic operation” flight. In the clothes of his son, who received the flight as a “Bar Mitzvah gift” he hid a camera and films. He flew a light plane to the vicinity of a nearby Arab village and took photographs of the outskirts of a village against which retaliation was planned. The details of the event became known to the family only a few years after the end of the British occupation.

Iddo Gal clarified that his grandfather “helped the kibbutz with camouflaging some guard posts (all based on his WWI experiences). And he was in charge of one of the many weapons caches in Yagur (there were dozens, hidden all over the kibbutz)…. When the British found in June, 1946, the largest weapons cache in Yagur, they arrested all the men who were sent to a detention camp…. He spent six months there with all the other hundreds of men who were taken from Yagur. He later produced a series of drawings of life in the camp.”

Back to Yoram Gal’s account:

[At Kibbutz Yagur] he started to create paintings from the adjacent Zvulun valley, the mount Carmel cliffs rising above the kibbutz, sights from the nearby Druze village Isfiya, people and animals, daily kibbutz life…. The fruitful work and passion was not displayed via formal exhibitions, yet Erich presented his works on various occasions and each member could come in to the family’s “zimmer”—as the small apartments were called at the time—and look at his paintings. As was customary in those days, he hung many of his paintings in public buildings and enjoyed giving original works of charcoal sketching, engraving, and painting to members of the kibbutz as gifts.

With time, Erich was formally recognized as a working artist, and he was “allowed” three days a week to pursue his art, in the spacious “atelier” that was built for him on a roof overlooking the Zevulun Valley…. His last years in the kibbutz were difficult both personally and artistically, due to the long illness of his wife, who had died young in 1955.

Acre and Haifa: 1957-1973

In 1957, at the age of 60, Erich Glas left the kibbutz for the port city of Acre. Yoram Gal wrote:

Through conversations with his Arab neighbors, riding with local horse-drawn wagons, and drinking coffee with the fishermen, he got to know all the corners of the city and acquired many friends. Everything he saw was documented and recorded by his camera. When he was asked to hold a photo exhibition marking the 10th anniversary of the “liberation” of the city in 1958 [Israel became an independent state on 14 May 1948], he went on to meet and photograph residents of the temporary newcomers’ camps, street peddlers and steel factory workers.

I learned more about Glas’s third wife from Iddo Gal: “Ziva Dioshka was born in Hungary. She was 37 years younger than Erich. They met in Acre after he had moved there from the kibbutz and got married within a few months (in 1958). They did not have children together.”

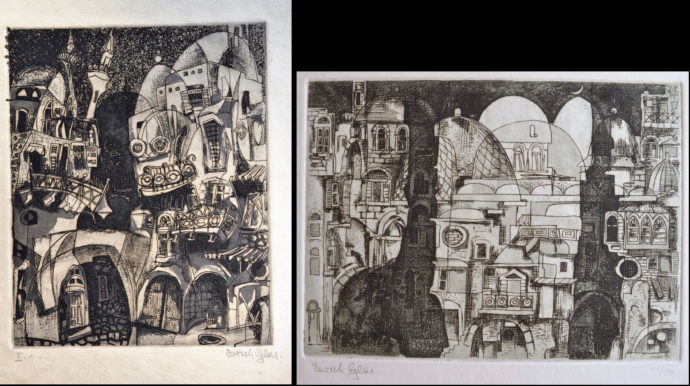

Erich Glas, pair of etchings that I believe were made after he left the kibbutz. © 1942-2018 Erich Glas Estate

Yoram Gal wrote that Erich and Ziva “had fruitful creative harmony between them, despite (and perhaps because of) the big age gap between them. After their marriage, they moved to the heart of the Old City…in a large house from the days of Napoleon.”

Out of the many rooms in the house, Glas allocated his art in three rooms: one for printing room, one for painting, and a darkroom for photography. He was happy. For the first time in years he could now work in ideal conditions, with his time utterly devoted to his art. In the fertile years that followed, Erich returned to intensive work on the delicate and work-intensive technique of etching, and in his paintings, he used lighter and brighter colors than before.

Following the Six-Day War in 1967 and the decline of relations between Jews and Arabs, Erich and Ziva decided to leave Acre. After some contemplating, they chose the city of Haifa, where they bought a small apartment on the slopes of Mount Carmel. The transition to Haifa in 1969 did not change the themes of Erich’s paintings, as before he continued to be interested and fascinated by Acre and its landscapes, as well as Mediterranean views and people set against all of these.

At the age of 72, his kidneys started suffering due to an infection from an operation carried out years earlier…. When his condition deteriorated, he felt that his life was nearing an end, and encouraged by the family, started recording his life story/memoirs; but whenever his condition improved, he would quickly opt to “not waste time” documenting the past and would happily reengage in creation.

He died in January 1973 at the age of 76 and was buried in Haifa.

Leilot

I asked Lev and Iddo Gal if photographs of the 1983 retrospective existed. Iddo initially said the exhibition had been photographed but that he was not sure we knew where the photos were. Then Gal said he “had a lucky moment today during a break when I dug out a box which had some CD backups and copies of some of Erich’s stuff, and it happened to have a video from the exhibit. I think I got it from Yoram (Hagar’s father) many years ago, and forgot I had it.”

Gal shared the video and noted that it included a segment showing someone turning the pages of Leilot. “This is an unusual piece of work, as it was published in 1942, during WWII.”

A pair of screen shots from the 1983 video showing someone turning the pages of the Erich Glas book Leilot. (Courtesy of the Erich Glas Estate)

This segment, even blurry and brief, told a powerful story with stark imagery. The first plates show the sleepless artist compelled by Death to create Leilot. The middle images portrayed the horrors of Nazi-controlled Europe, while in the last images the artist and fellow Jews were shown strong and defiant. I was interested enough to make these the focus of an article, and I shared my excitement with Lev and Gal.

Lev shared more about the story behind the creation of this series: “During a few nights in 1942, Erich was lying down sick with high fever. While he was burning with high temperature, he was having horrific visions. Still feverish, he started making sketches, and once he got better, he set out to create the full series.”

Gal then referred me to a video that Yochai Avrahami, an Israeli artist who has taken an interest in Erich Glas, made with Ziva, his third wife, in 2010. Below is part of the conversation captured on video between Avrahami and Ziva Glas:

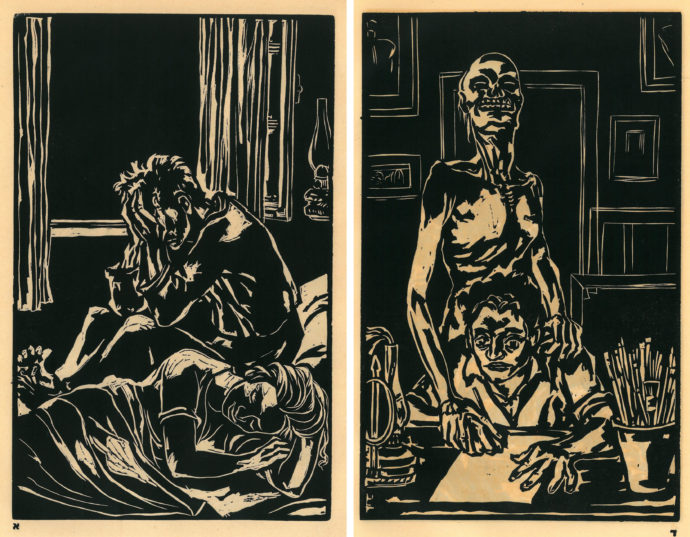

Erich Glas, Leilot, linocuts, plates 1 “Evening” & 4 “Death Speaks” (new to the 1945 edition), paper size 33 x 23.5 cm. © 1942-2018 Erich Glas Estate

LEILOT IMAGERY

A complete PDF of Leilot appears at the end of this post.

Yochai Avrahami: I don’t know if you’ve seen this. It’s a book of linoleum cuts that he published in 1942. That was during the Holocaust.

Ziva Glas: I’m not sure there was news. Israelis didn’t hear much about it. He [Erich Glas] said he had some illness. He was isolated for a week or more. In an isolator, yes. When he was there, the idea came to him to make a series of cuts about the atrocities.

Another woman’s voice: Do you think he was affected by his high fever or….

ZG: Yes, he said so. Like hallucinations.

YA: He shows someone waking from a nightmare and seeing all these images: wailing, getting more and more surreal and intense. He shows a concentration camp.

ZG: A concentration camp, near Weimar.

YA: In Buchewald.

ZG: Yes. I don’t know what she [Maria, Erich Glas’s first wife who remained in Germany] wrote to him. I don’t think she would have written to him. It would’ve been very dangerous. He wanted them [a publishing house in Palestine] to publish it, to distribute it. But they refused. They said, “No, you’re spreading havoc.” They also hid it because a lot of their families stayed there [Germany].

YA: So all these images are imaginary, right?

ZG: Yes.

YA: The communal grave, for example.

ZG: A deep hole filled with corpses. I don’t know where he took that, this communal grave, from. This is the beginning of his angry period.

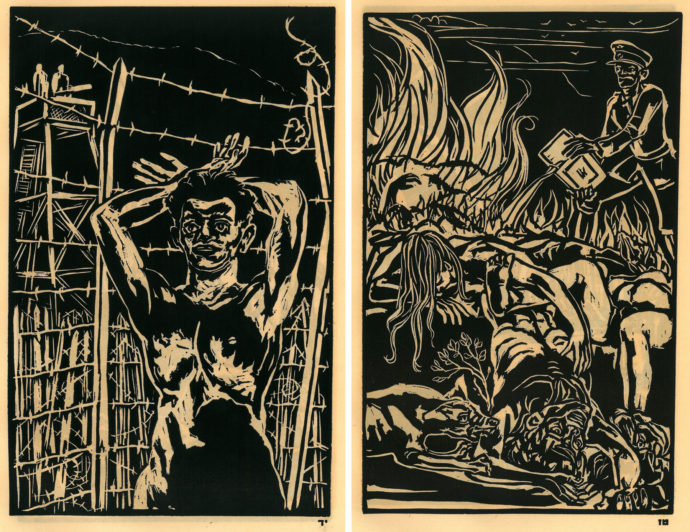

Erich Glas, Leilot, linocuts, plates 14 “Concentration Camp” & 16 “Burning of Corpses” (both were new to the 1945 edition), paper size 33 x 23.5 cm. © 1942-2018 Erich Glas Estate

Intrigued by Ziva Glas’s tone, I asked Lev and Gal what was behind her statements: “He wanted them [a publishing house in Palestine] to publish it, to distribute it. But they refused.”

Lev replied that in 1942 “the reality of what was actually happening in Europe was not clear to all. There were shreds of information, claimed by many to be merely rumors. After all, who could believe such atrocities were real. This was probably the underlying reason for the refusal of Davar, a reputable publication which Erich had worked with from time to time, to publish Leilot in Israel at the time.”

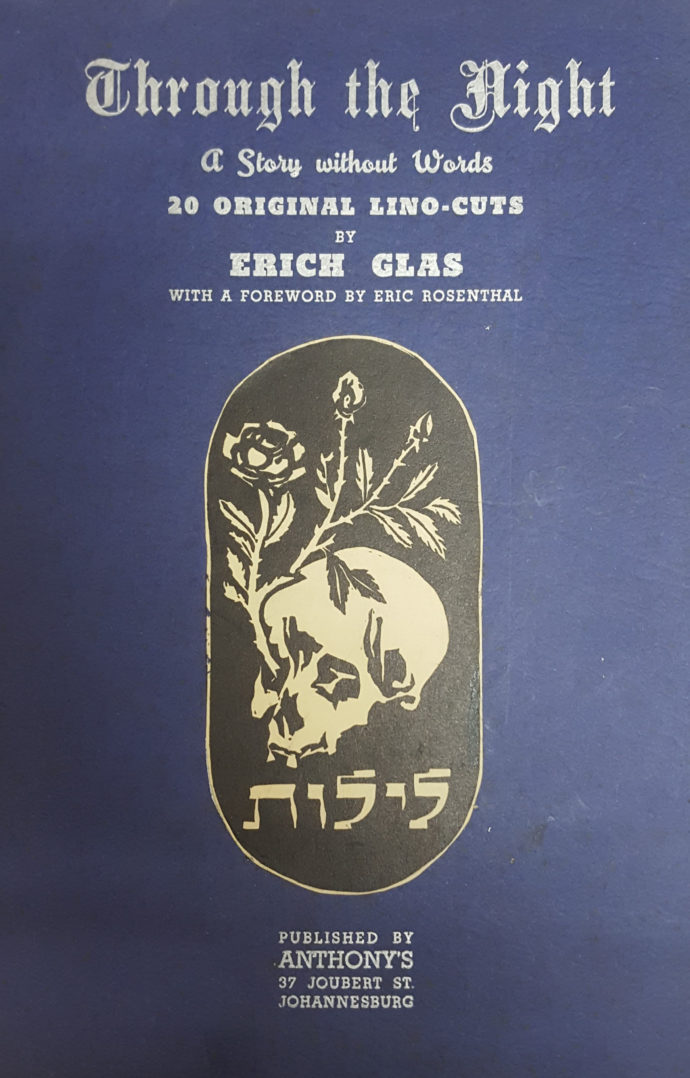

The cover of “Through the Night,” the English version of “Leilot” that was published in South Africa in 1943.

Iddo talked to Ziva about its publication history. “She said as far as she knows, after Erich got a refusal from a well-known publishing house in Israel, he arranged the SA [South Africa] connection privately through a relative of his [second] wife Susi who lived in SA and had a connection to the Johannesburg publishing company. She thinks the family in SA helped the publication from its own family funds.”

Lev added, “A South African publication was issued in 1943 in an English version of the series (the works had been originally titled in Hebrew, as they had been prepared to be issued in Palestine)…. The foreword was written in 1943 by the historian Eric Rosenthal.” The South Africa edition was limited to 200 copies numbered and signed by the artist.

She sent me the forward. In it Rosenthal wrote:

“There is something in the grimness and directness of the presentation of these pictures which reminds one of the famous old ‘Dance of Death’ series of the Middle Ages, the bursting of calamity over masses of helpless, idealistic folk, beset with problems and heady with tradition. Nowhere is it more strikingly shown than in the pogrom scenes, the old man carrying his sacred treasure through the flames, the barbaric figures of the Herrenvolk Stormtroppers, engaged in destruction and rapine. There follow glimpses of Nazidom in action, the concentration camps and mass shootings. To me perhaps the most heartbreaking of all the pictures is that of the refugees on their ship, and then the drifting corpses after she has gone down.

“Yet the most astonishing quality in Erich Glas’s work is that, in spite of everything, he remains an optimist. Tortured victims of the Nazis, out of the deepest depth of their despair, call out: ‘Arise and Fight!’ “

Erich Glas, Leilot, linocuts, plates 26 “Arise” & 28 (last plate) The New Dawn” , paper size 33 x 23.5 cm. © 1942-2018 Erich Glas Estate

The Palestine edition did not appear until 1945. Lev said, “The harsh description of death, destruction, despair, and then resurrection and hope by Erich Glas came to light in Israel only when the holocaust started becoming known to its true and horrifying dimensions.”

Leilot’s convoluted publishing history was further explored by Gal. “We have wondered why Erich has published outside of then Palestine, and went to SA in 1943.” He noted that the later edition gave “credit in Hebrew to the special edition in SA” and it had “a new introduction in Hebrew (a very poetic piece by Dov Shtok-Sadan).” He found no publication date or edition size in the Hebrew edition. The Hebrew edition added eight plates not found in the SA edition.

But in a later email he added:

Now I have a bit of info which may help [date the latter edition]. In looking through the [Leilot] booklets, I have two set aside for my daughters. So I haven’t examined them in years and, upon opening, realized that one has a personal dedication (in Hebrew) from Erich to my father Uziel, dated 1945. The actual title graphic is dated by hand 1942 by Erich. From this I deduce that he created the prints in 1942, they were published in SA in 1943, and in 1945 in Israel (then Palestine) and this is when he gave a copy to his eldest son Uzi, who by then was 23 years old (the other boys were much younger). All this makes sense, because WWII ended in 1945, and by 1944 the Nazi atrocities were already in the open. Hence it is sensible that the publishing house of the Kibbutz movement went ahead and published it.

Iddo Gal scanned and shared with me in the complete 1945 Leilot portfolio. While Hagar Lev translated the index of the plates and indicated which plates were new to the 1945 edition. All of the images are boldly cut with minimal shading. The image opposite the forward shows the artist contemplating his work. The story begins with three plates depicting the artist’s nightmare and then an image of Death guiding the artist’s hand. The next nine plates show the initial atrocities inflicted on the Jews by the Nazis. The next ten plates begin with concentration camps, then mass executions, finally the desperate flight of Jews at sea. The next plate presents a full male figure (the artist?), arms raised, alarmed by all the horrors in Nazi Europe. Death reappears in the next plate, this time sitting on the prone artist. Perhaps Death is releasing a dove. The last three plates are ones of great resolve. Jews, no longer wanted to be victims, are seen rising up and arming themselves. The apparent lesson is: “Never again.”

The years in which Leilot were created and published were ones of great uncertainty in Palestine (the future Israel). So understandably preservation of materials pertaining to the creation of Leilot were lost or misplaced. One can hope that perhaps the preparatory drawings for Leilot can yet be found. Maybe letters that were exchanged leading to the two publications of Leilot can also be found. And just maybe the linoleum plates for Leilot can be found. Until then the story of Leilot will not be complete.

Complete Leilot

Click below to see the entire 1945 Hebrew edition of Erich Glas’s Leilot. The pairs of images are to be read right to left as would be done in a Hebrew publication. Advance the PDF by scrolling down.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/leilot-erich-glass-traumatic-creation/trackback/

Deeply indebted to Hagar and Iddo for sharing (and to you for compiling) this history of the life and work of Eric Glas. We were close friends with Uzi, his wife Ahouva and daughter Tamar from 1980 when we lived in Dresher, PA. Through them, we met and became close friends with Yoram Gal, his wife Nora and their children, with whom we remain in close contact to this day.

Through the generousity of the family, we have several copies of Eric’s work hanging in our home, and a digital library of about 30 works which Iddo gave us. Your blog has deeply enriched our knowledge of the life and work of Eric Glas in both Germany, Palestine and Israel.

Thank you,

Larry and Meira Maltin

Very interesting body of work, they are very powerful images. Some of the images remain me the works of artists during the Mexican Revolution, from La Grafica Popular Mexicana.

The post is very well researched, it transports us back and for through generations and family stories.

Corina del Carmel

Pingback: Erich Glas: Two Editions of “Night”