Kibbutzim in Eretz Israel

“BeShir oovCheret” (“In song/poem, in print/engraving”), c. 1939, Achdut (unity) cooperative printer, Tel Aviv

INtroduction

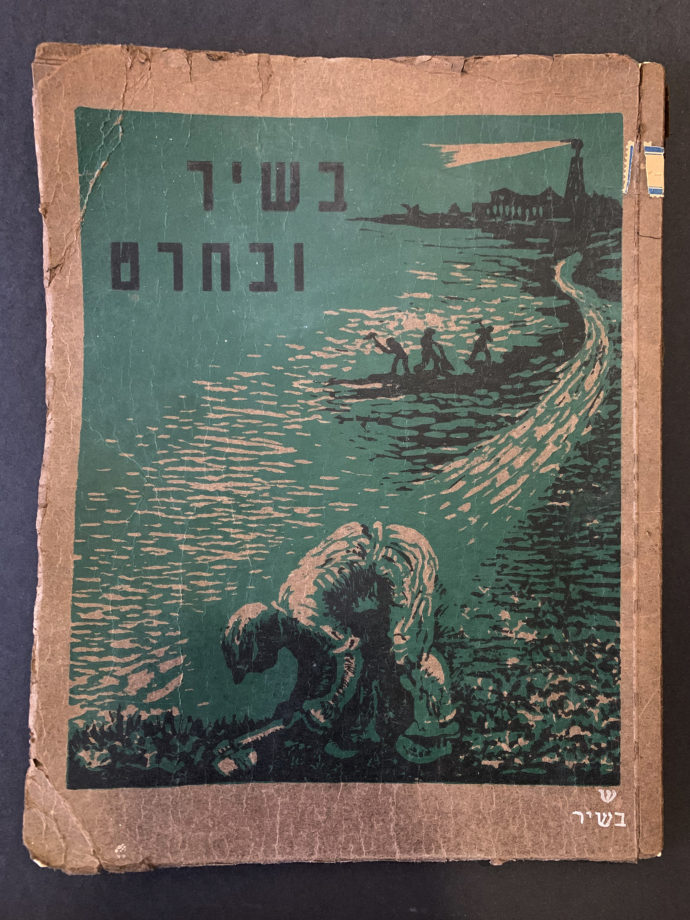

When you patronize a retailer, that seller is likely to feed you related products. This happened after I purchased Leilot, Erich Glas’s 1942 (revised and enlarged in 1945) woodless narrative of the Holocaust in linocuts. (See two ART I SEE posts on Leilot at here and here.) Glas created his book while living on a Kibbutz Yagur in the early 1940s in what Jews would call Eretz Israel–the Land of Israel. The rest of the world would call the land Palestine, a British mandate since 1920. Not until 1948 would the western part of Palestine become Israel. Well, J-B, the seller of Leilot, offered me BeShir oovCheret. While this book was not in my preferred illustrated-without-text format, it did contain a number of strong relief prints–presumably linocuts–alternating with pages of poetry. And unlike Leilot, which stressed the horrors Jews were then facing in Europe, BeShir oovCheret focused on contemporary life on kibbutzim in Eretz Israel. Yet both books had something important in common. Leilot ended with Jews in Eretz Israel arming themselves to prevent future holocausts, while BeShir OovCheret showed day-to-day life in armed fortified settlements.

I thank Hagar Lev, a granddaughter of artist Erich Glas, for providing translations. Not a professional translator, her efforts came with this caveat: “These translations throw me above, beyond and well outside my comfort zone, from the old-style Hebrew language to the many historical, biblical and other references.”

Here is her note on translating the book’s title: “The ‘Be’ (pronounced ‘beh’) before ‘Shir’ and and ‘Oov’ before ‘Cheret’ are the Hebrew connectors, in this context both meaning ‘in.’ ” And “Shir” can be both song or poem; while “Cheret” can be both print or engraving. Hence she translates the title BeShir oovCheret to mean “In Song/Poem In Print/Engraving”

Preliminary texts

The attitude behind this book is clearly stated on the title page directly below the title: “A collection of poems and prints/engravings dedicated to work, conquest and defense.” Here “conquest” means turning barren land fruitful and does not have military connotation. Below that reads: “Publication: HaKibbutz Artzi Hoshomer Hatzair.” HaKibbutz Artzi was a Marxist collective of kibbutzim all over the land; while Hashomer Hatzair translates as “The Youth Guard,” somewhat like scouting.

Jewish Virtual Library website (link) states: “Hashomer Hatzair, the initial Zionist youth movement, was founded in Eastern Europe on the eve of the First World War. Many Jewish youth, affected by the process of modernization which had begun among Eastern European Jewry, sought a means of maintaining their Jewish identity and culture outside the stifling barriers of the shtetl and of Orthodox Jewish life. On the other hand, they were troubled by the crumbling of the foundations of society around them and by the growing anti–Semitism which threatened their very existence…. Hashomer Hatzair forthwith adopted a Zionist ideology and stressed the need for the Jewish people to normalize their lives by changing their economic structure (as merchants) and to become workers and farmers, who would settle in the Land of Israel and work the land as “chalutzim” (pioneers). They were influenced, as well, by the burgeoning socialist movement, and they dreamt of creating in their new homeland a society based on social justice and equality.”

Regarding Kibbutz Artzi, the Jewish Virtual library (link) states: “The Kibbutz Artzi is a federation comprising 85 kibbutzim founded by the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement…. In 1927, the kibbutzim of Hashomer Hatzair, until then individual and separate settlements, decided to join together for greater mutual aid and to provide a focus for the world organization…. At its inception the Kibbutz Artzi numbered four kibbutzim, with 200 members…. In the first years of the new state the Kibbutz Artzi took an active role in settling new kibbutzim. The kibbutzim played an important part in reclaiming the barren lands, in absorbing new immigrants and in securing the borders of the country.”

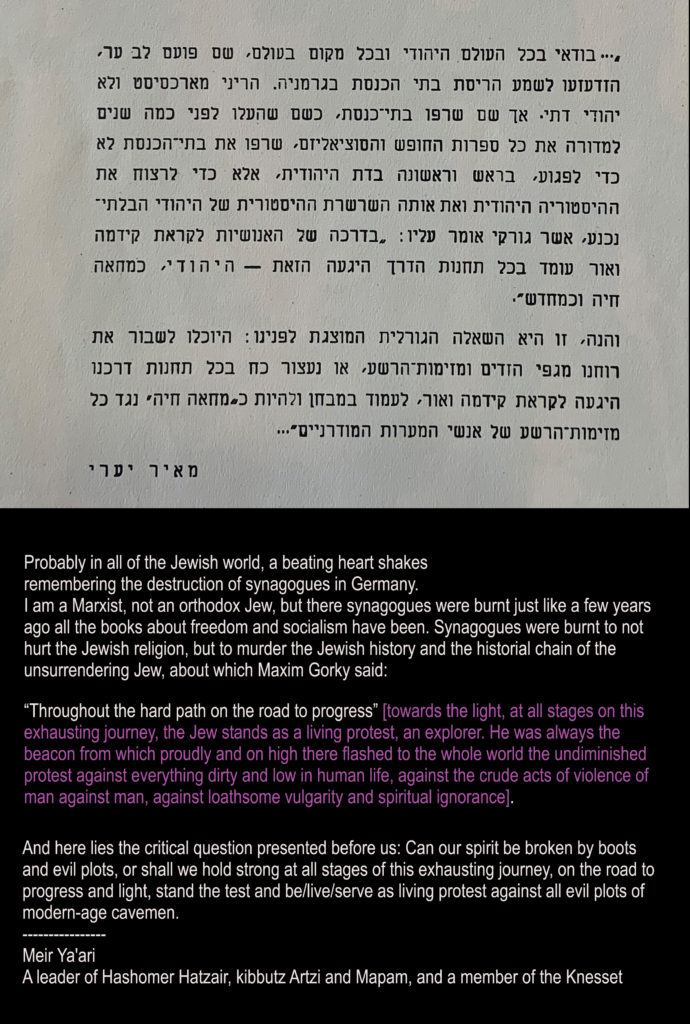

Only the beginning of the Maxim Gorky quote appears in Hebrew. The rest of his quote is in purple and bracketed. It is from an article he wrote: “The Jewish Question and the Russian Intelligentsia.”

Before the first linocut appears is a brief statement by Meir Ya’ari that leaves no doubt as to Marxist political bent and determination behind this book. He wrote: “Can our spirit be broken by boots and evil plots, or shall we hold strong at all stages of this exhausting journey….” These are defiant words. He dared to ask: Do the members of kibbutzim–the likely audience–have the courage to overcome “all evil plots of modern-age cavemen.” What did Ya’ari mean by “cavemen”? And what did readers of this Kibbutz Artzi publication read “cavemen” to mean? I’ll comment on that at the conclusion of this post.

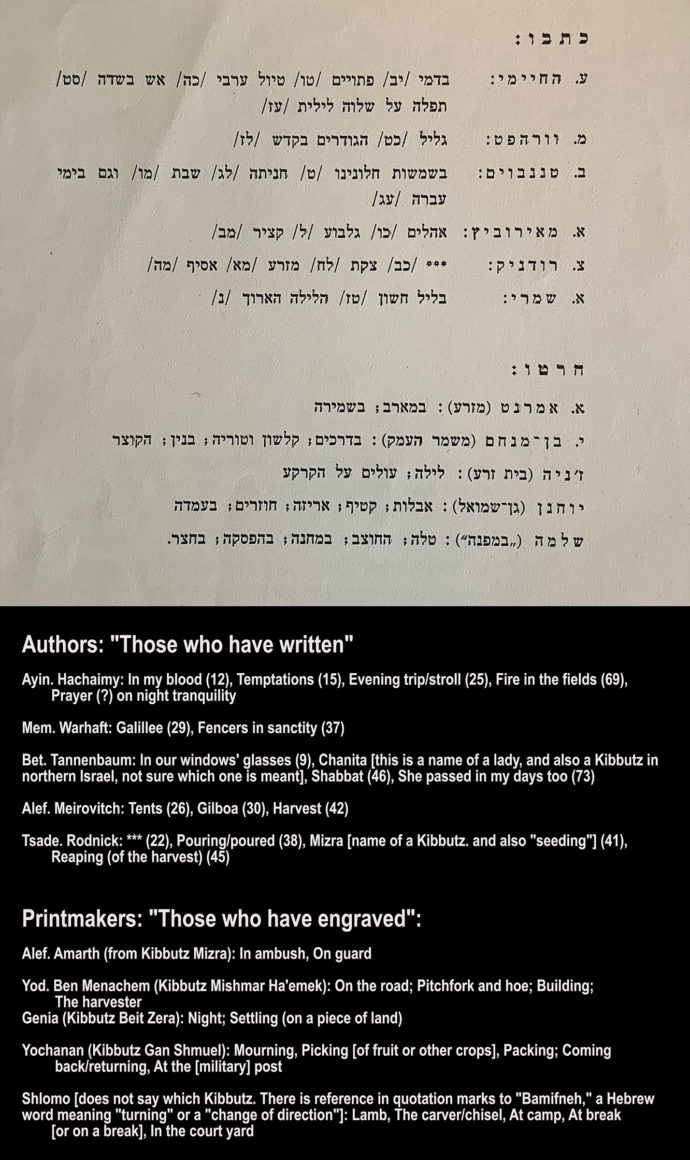

Above is the index to BeShir oovCheret with Lev’s translation. She also sent me this note: “As for the names and titles on page 4: the names appearing there are not full, they are written in the format of first initial (e.g. the Hebrew letters of Ain, Alef, Beit, etc.) and then a full last name. I have written these in English best as I could. Note that the last names’ spellings might not be accurate, there are different ways to spell these.”

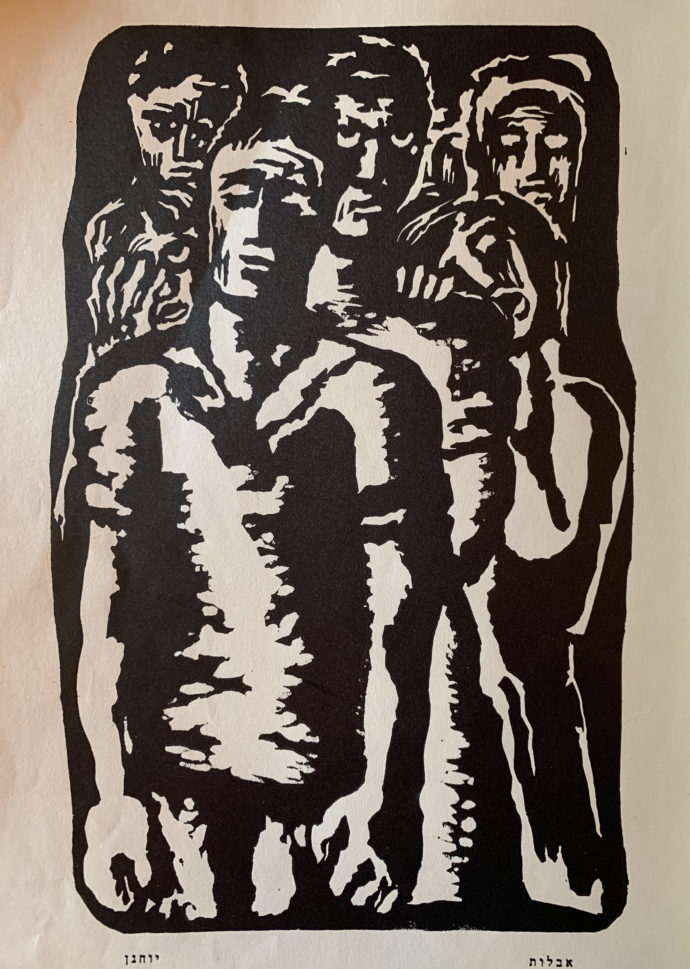

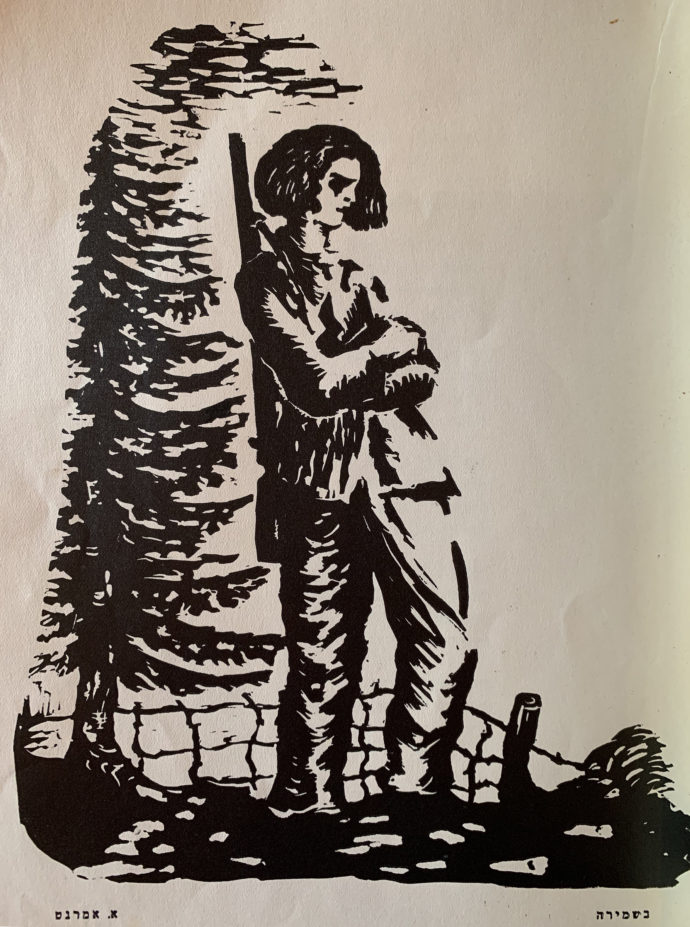

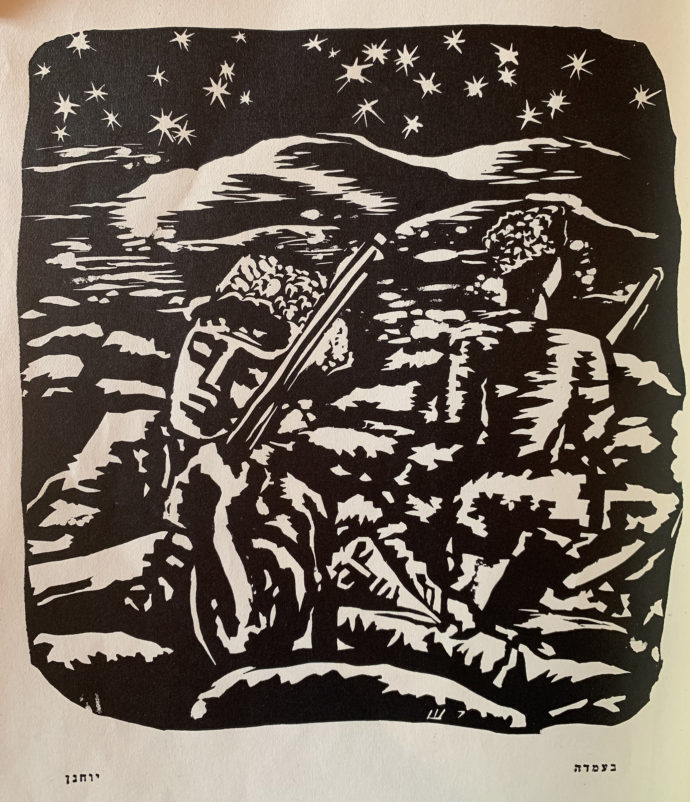

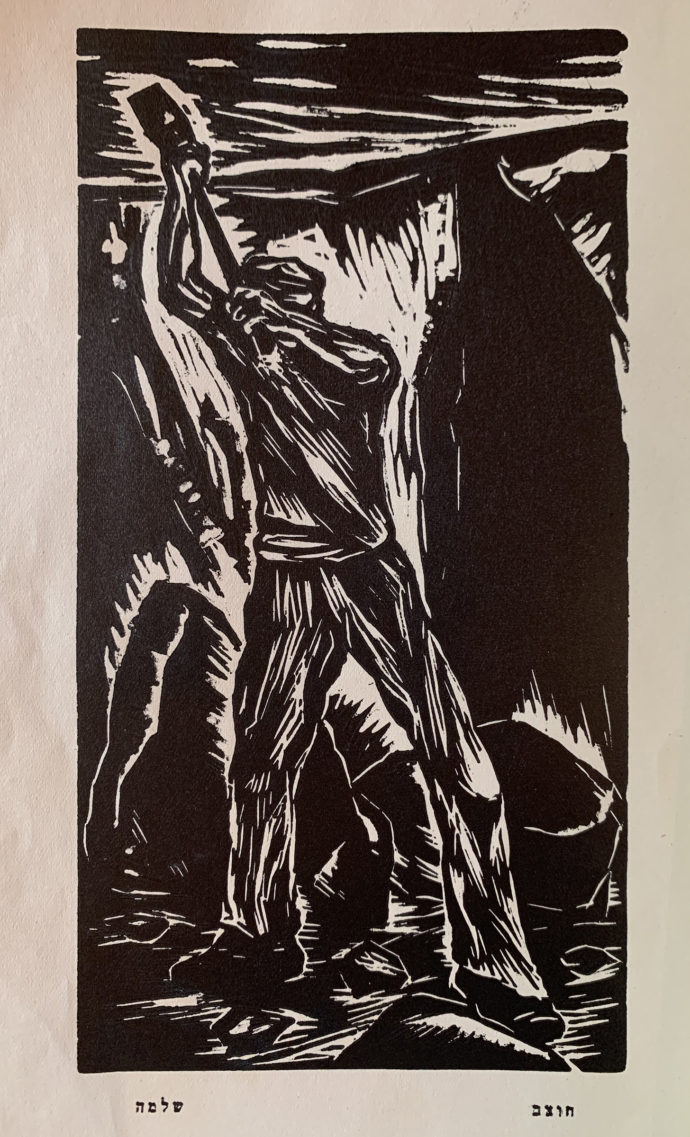

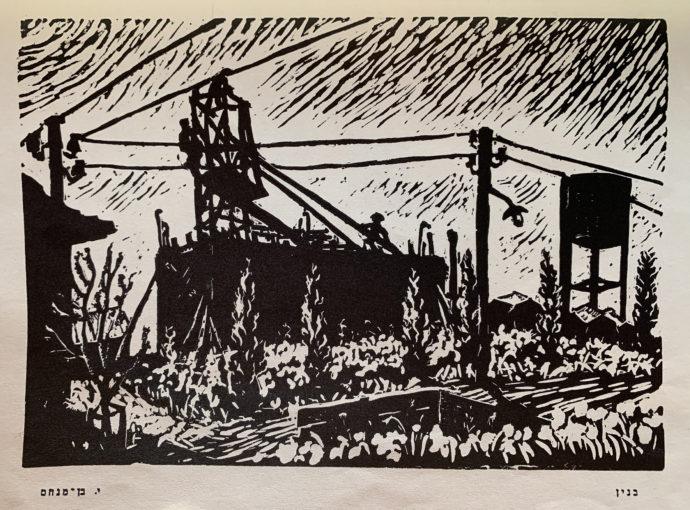

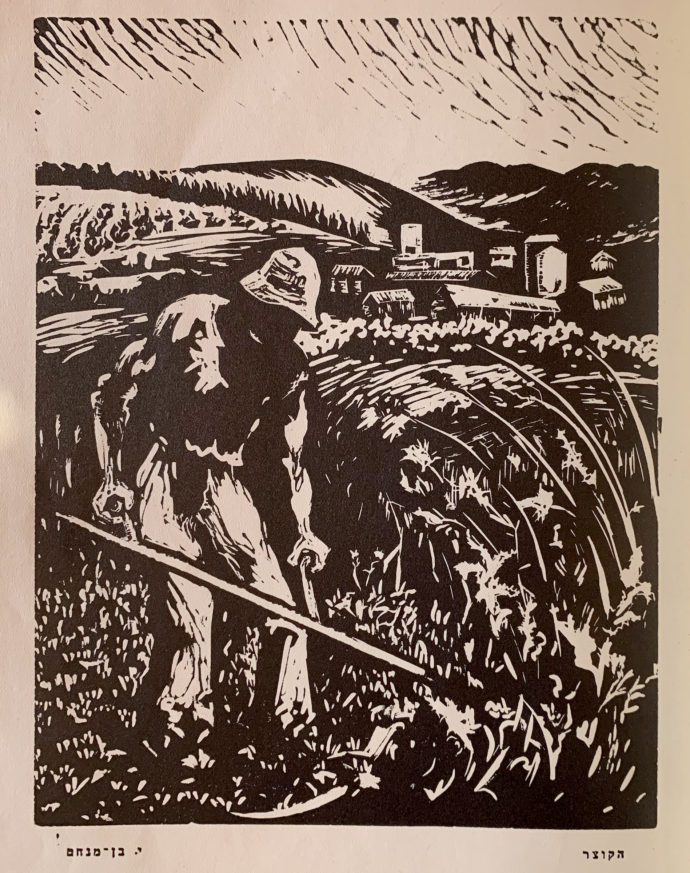

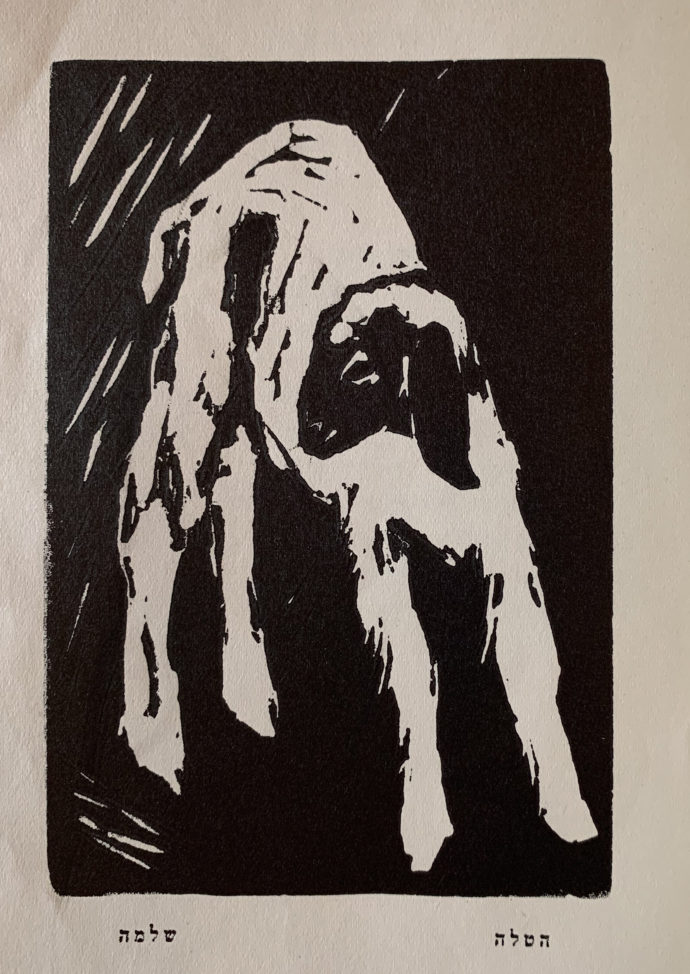

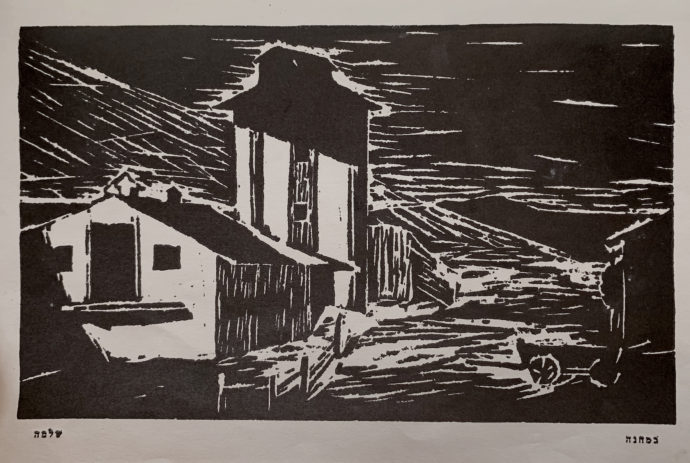

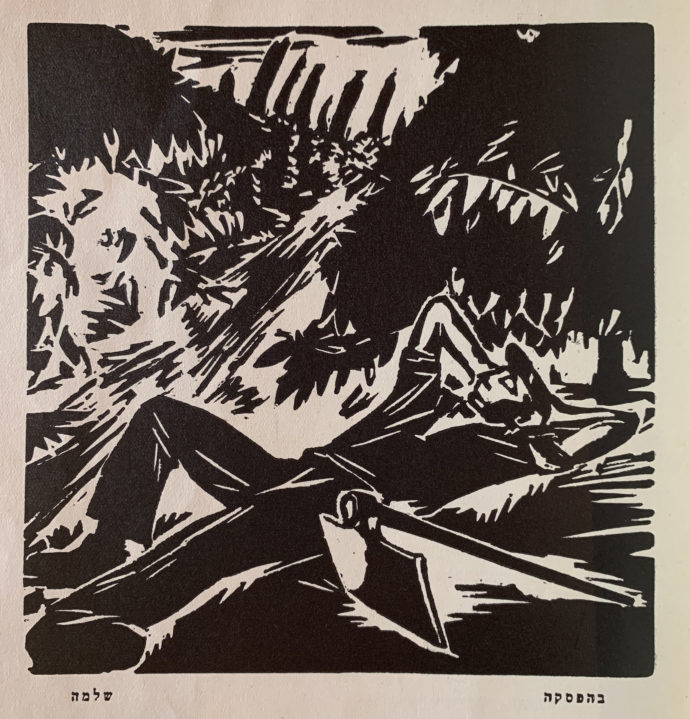

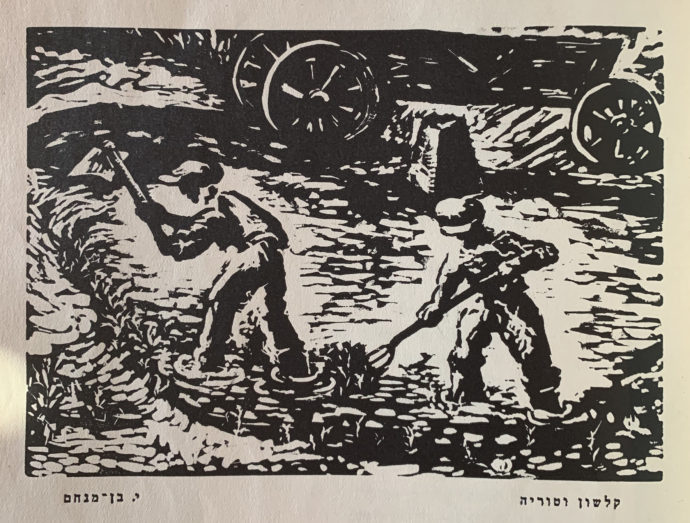

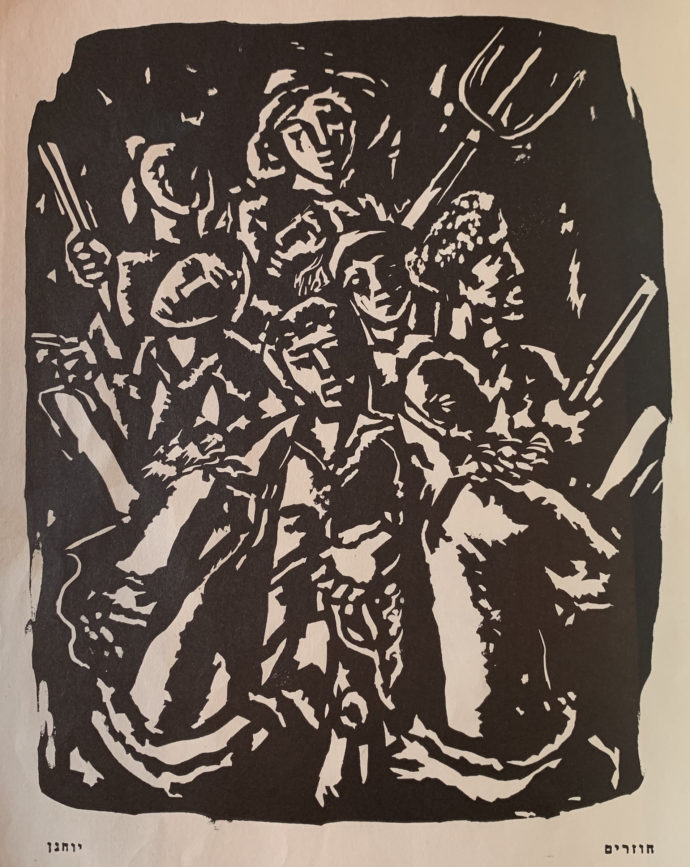

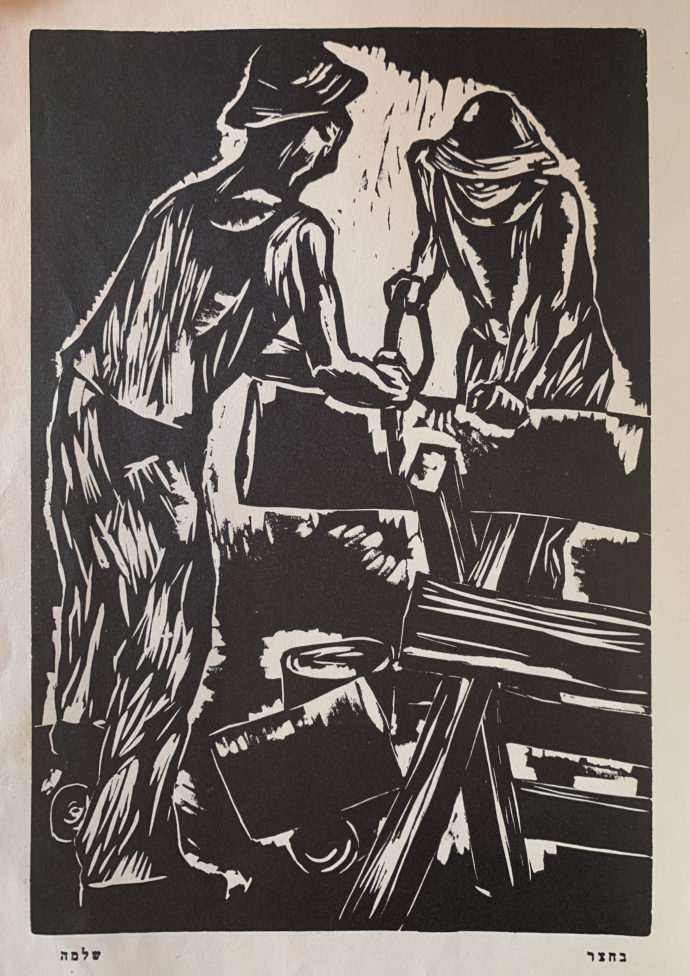

Among the illustrators, all but Shlomo were listed with the name of their kibbutz. And the last three of the artists were listed with their first name. Here Lev notes: Genia is “a common abbreviation of the female Russian name ‘Eugenia.'” As to full names of the artists, I believe “Yochanan” is Yohanon Simon (Berlin-born Israeli, 1905-1976). J-B, who sold BeShir oovCheret to me, named Yohanon Simon in his listing for this book. Checking the names against the book Fifty Artists (Massadah Publishing House Limited, Tel Aviv, 1955), “Shlomo” could be Shlomo Itzkovitz (Polish-born Israeli, 1896-1973) or Shlomo Salomonovitz (Austrian Empire-born 1902-1958). But that is only guess work.

Poems & Prints

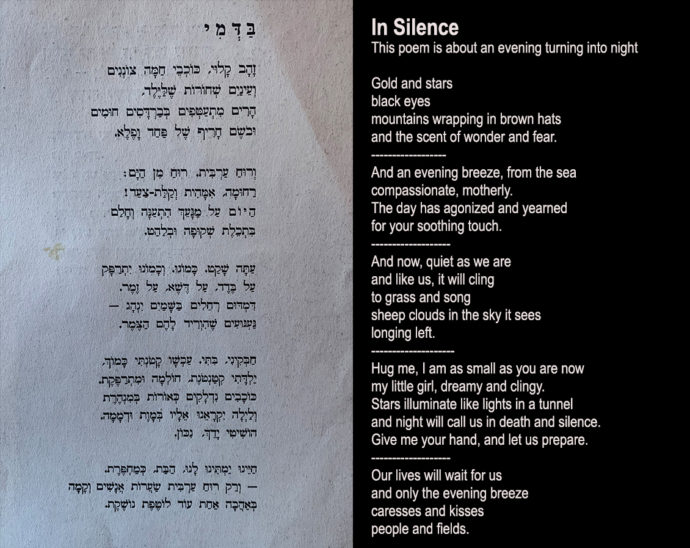

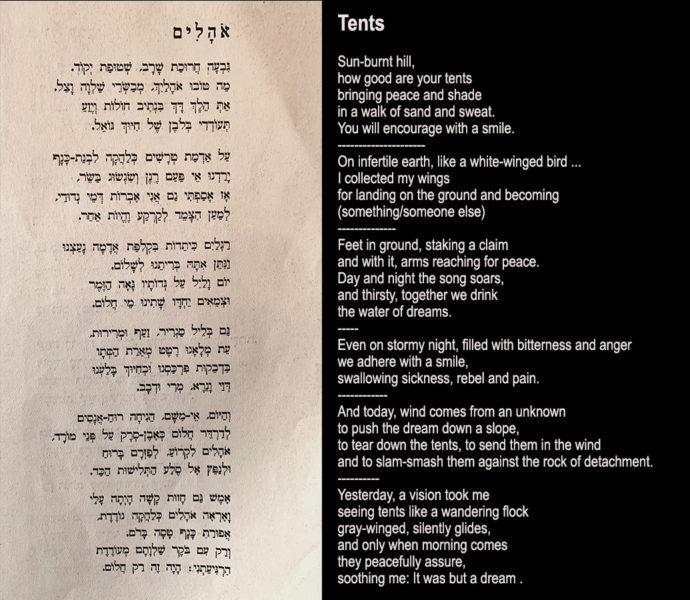

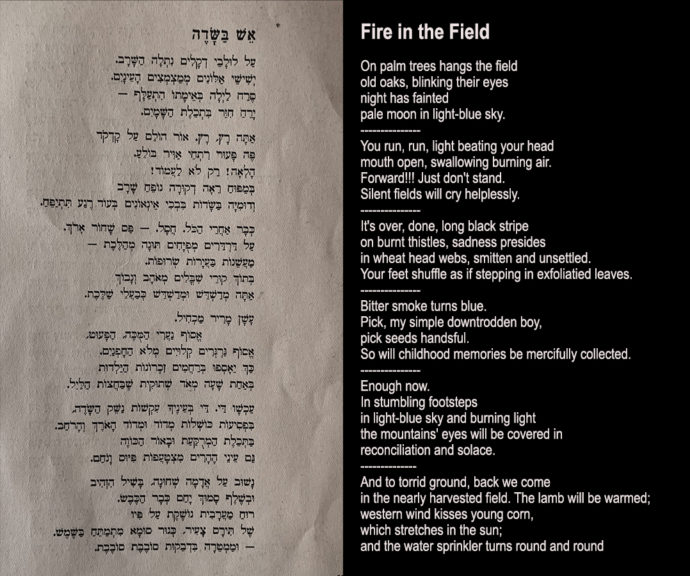

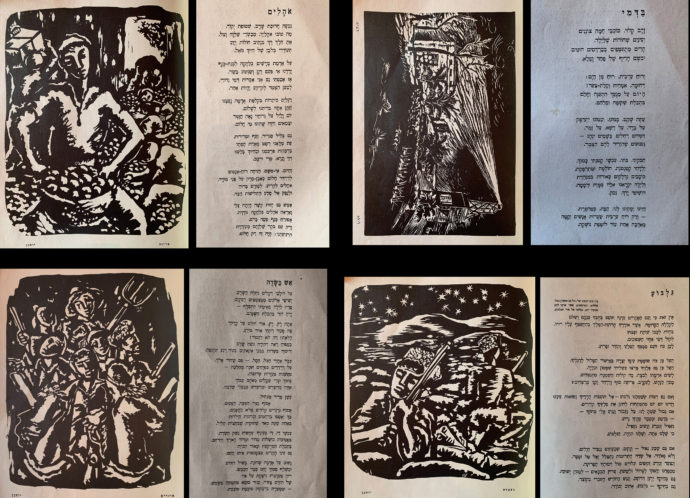

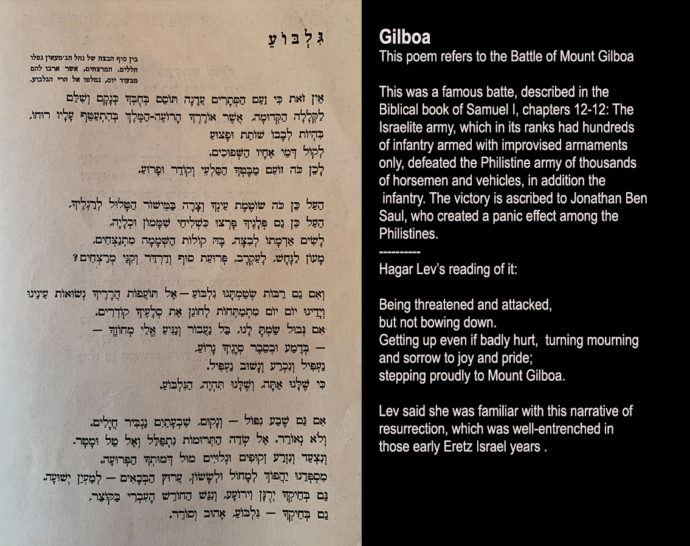

I chose four spreads in BeShir oovCheret where a complete poem appears on the right-hand page and a relief print on the left-hand page in hopes that the placement indicated that the image was in some way an attempt to visualize the poem. Then I asked Hagar Lev to attempt a translation or at least commentary of each poem. Here are the four spreads:

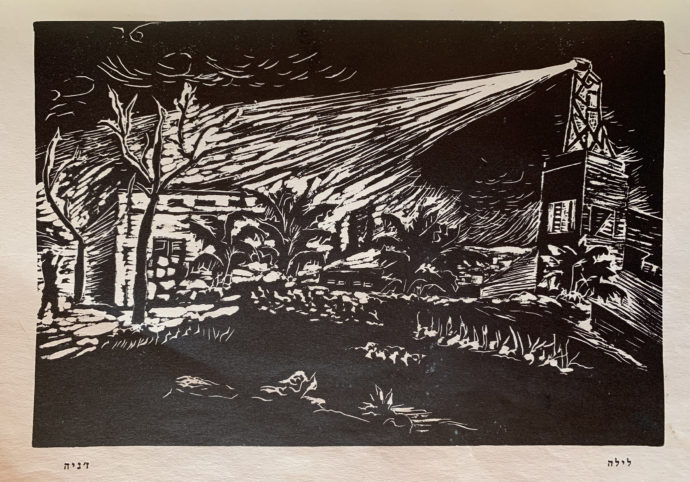

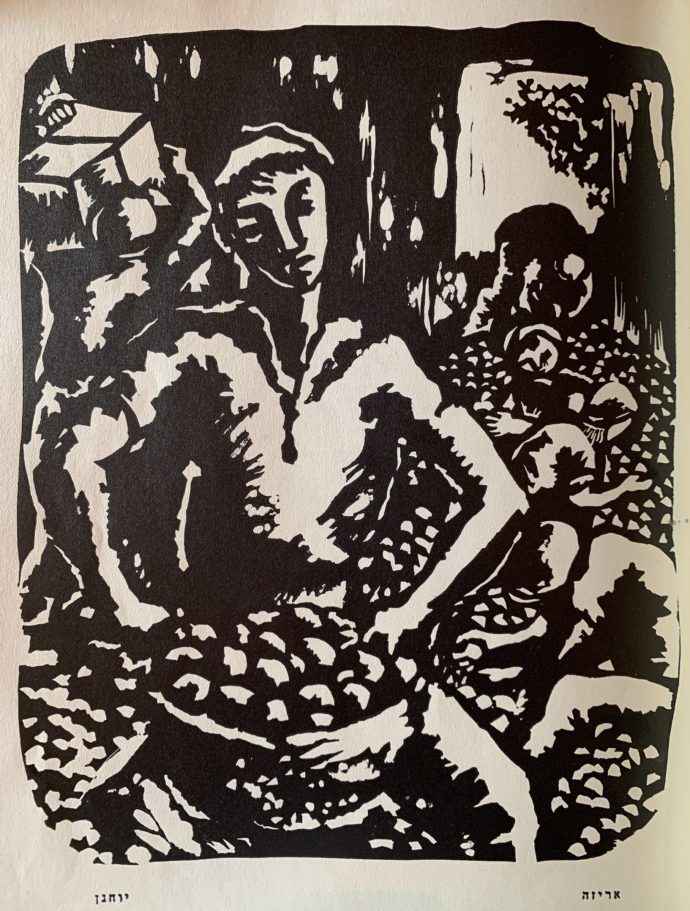

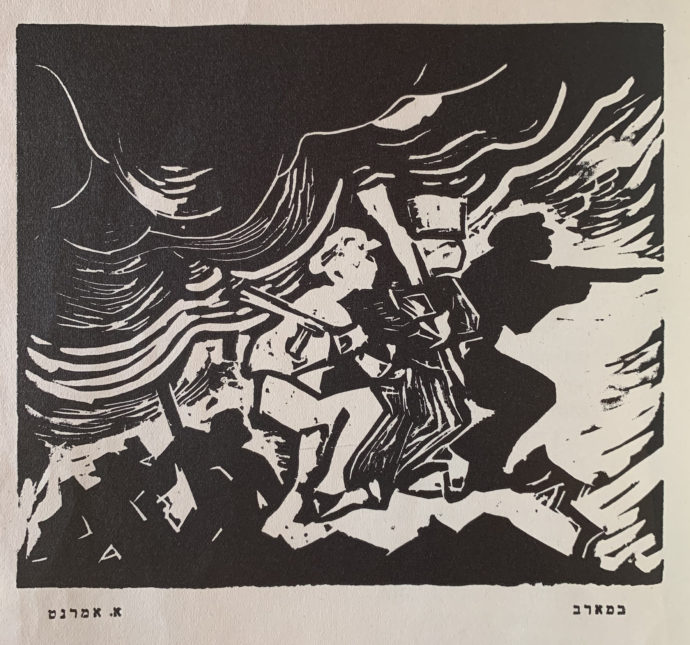

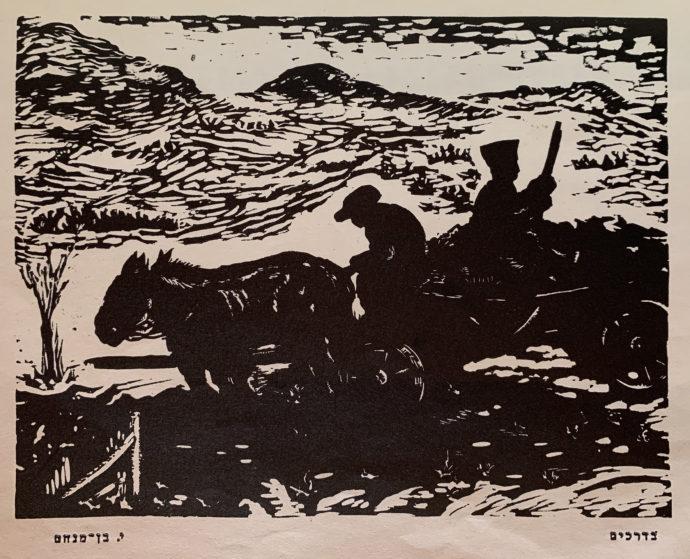

Images: (Top Right) Genie, “Night”; (Top Left) Yohanon Simon; (Bottom right) Yohanon Simon, “In Battle Position”; (Botton Left) Yohanon Simon, “Returning.”

And here are Lev’s translations/commentary of each poem:

For info on the Battle of Mount Gilboa, go to: https://www.historynet.com/learned-mount-gilboa-1006-bc.htm

Album of plates

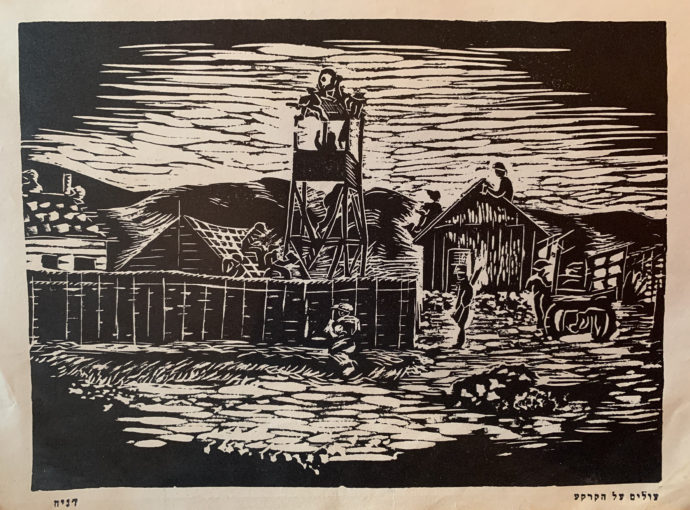

In order of appearance are all of the plates in BeShir oovCheret. I believe they were printed from the linoleum–I assume–blocks if only because the opposite side of the paper was left blank. The pages in the book measure 10 3/4″ x 8 3/8″ ( 27.5 cm x 21 cm). Vertical images like the first one nearly fill the page. Horizontal images will appear small in this post because of the width restrictions of this blog format, but a number of the horizontal images also tend to fill the page.

Commentary

As so aptly delineated in the last image, kibbutzim needed to be fenced in with watch towers and armed guards and even searchlights. Seven of the 18 plates show long-barrel firearms. And the determination of kibbutz members is stressed in the first plate, the only plate that stands alone without a poem opposite it. Note the clenched fists of the man in front. The reason these settlements required such defenses and arms was the antipathy their presence engendered from Muslim communities that lived on and worked the land for centuries. From the Jewish/Zionist perspective kibbutzim represented a return to the homeland and a matter of survival. From the Palestinian perspective kibbutzim represented an unwelcome and dangerous intrusion.

I grew up in the 1950s with a Fort Apache play set like the one above. I use to faithfully watch “Rin Tin Tin” on TV Saturday mornings. So no wonder I would want a set like this.

When I first viewed the images in BeShir oovCheret–especially the last plate–I couldn’t help but find visual parallels to Fort Apache. With programming like “Rin Tin Tin,” I learned that the West was “won” by subduing the “Indians,” that white people had a right and a destiny to remove “Redskins” from the land. What was unapologetically taught during my childhood and for decades to come can only be described as a whitewash of the genocide of Native Americans. America is a double edge sword: A land of great freedom codified by its Constitution and a land that woefully fails to adhere to its promise. (I’m not even talking about transporting Blacks from Africa for lives of servitude.) Israel is very similar: Indeed it is a beacon of democracy in the Middle East and a source of great pride for Jews worldwide, but that doesn’t mitigate the fact that Israel was built on the removal of many indigenous Muslim inhabitants not only within the borders of the State of Israel but later via settlements in large tracts of the Palestinian West Bank.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/kibbutzim-in-eretz-israel/trackback/