Gustav Wolf: His Monster Menagerie

Introduction

This is the second of five ART I SEE blog posts on the German Jewish artist Gustav Wolf (1870-1947). The five posts represent the five portfolios of prints of his in my collection.

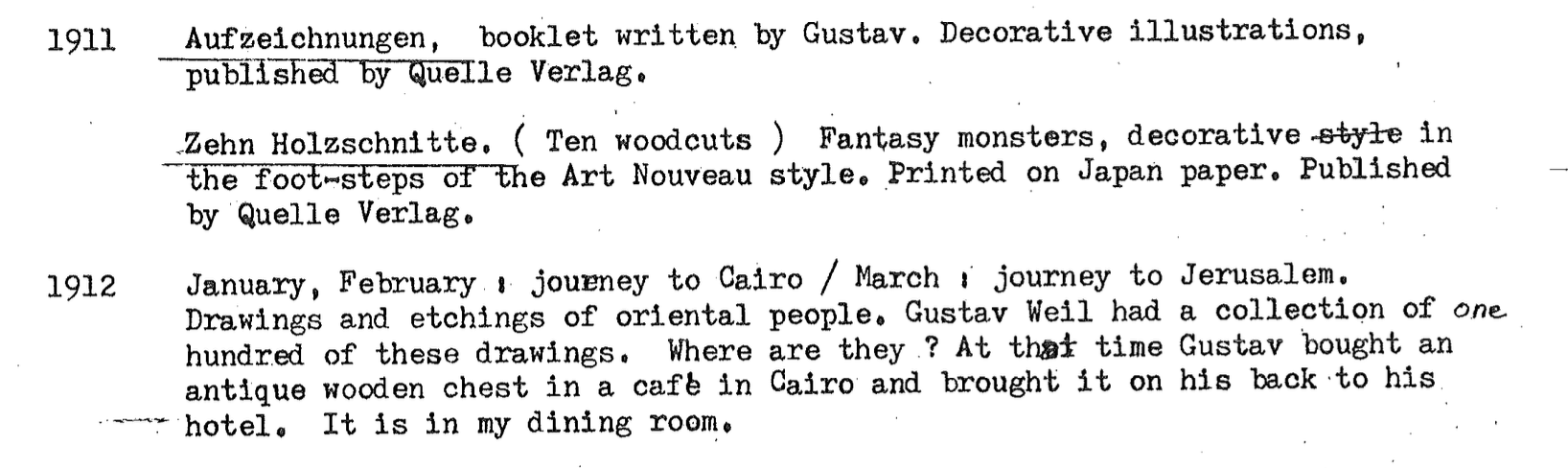

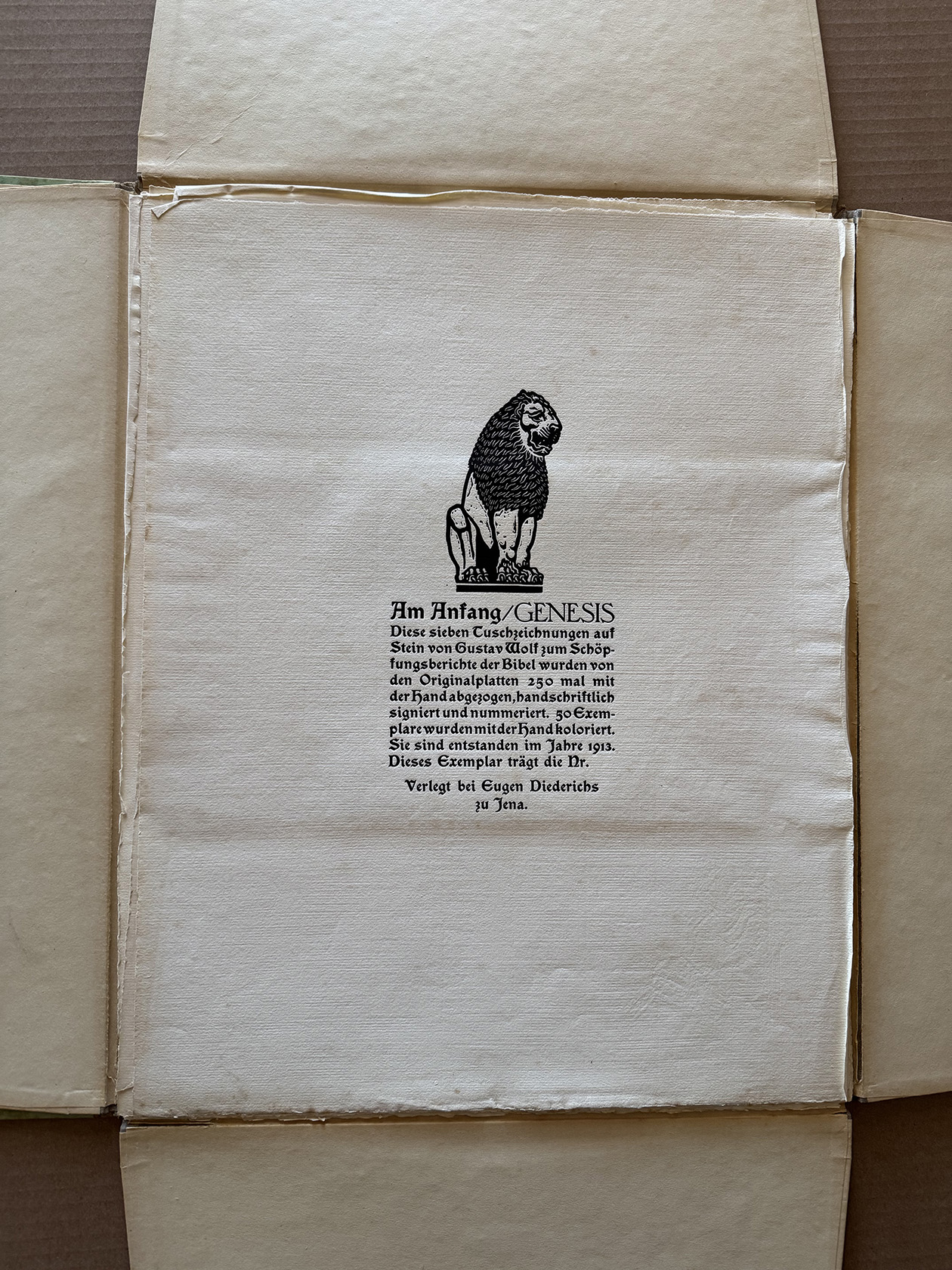

The first post was on Confessio: Worte und Zeichen (Confession: Words and Signs) (LINK), which he initially worked on in 1908-9. Seven of these ten dramatic woodcuts included insets of essays by Wolf. He added an exuberant title page when it was finally published until 1922 by Eugen Diederich in Jena, Germany.

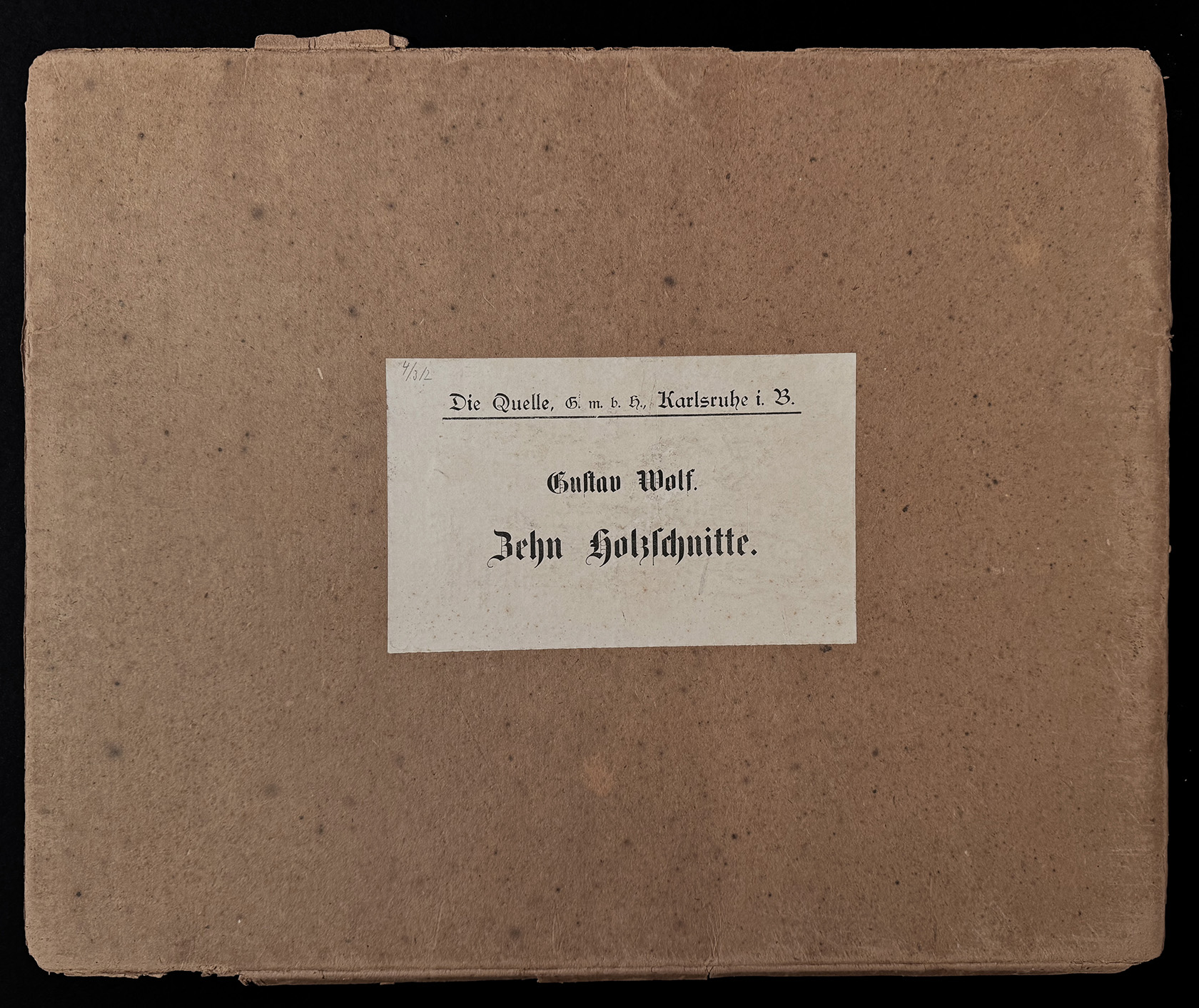

This post features his first published cycle of prints: Zehn Holzschnitte (Ten Woodcuts). It was created in 1910 and published in 1911 by “Verlag der Quelle” in Karlsruhe. While the woodcuts in Confessio are striking in scale–about H 23 3/4″ x W 18″–and imagery, all but one of the 10 woodcuts in Zehn Holschnitten are petite, about 4″ square. While the Confessio woodcuts are black and white, the Zehn Holschnitte ones were printed from two blocks, a muted color block and a key block in black.

My source material for my Wolf posts comes from Gustav Wolf: Das Druckgraphische Werk (The Graphic Work),” the 1982 catalogue raisonné of Wolf’s prints by Johann Eckart von Borries. I’m grateful that art historian Daniel Fulco translated von Borries’ essays from German to English for me. But the catalyst for my Wolf posts came in October 2023 when I received an email from Leigh Firn: “I came across your blog while I was researching Gustav Wolf. He was my great uncle (my grandfather’s younger brother). I was happy to see that you enjoyed his work. In the event that you are interested in a little more background about him I’d be happy to share with you what I have.” He then provided photos of Wolf, images of paintings, prints and drawings by Wolf, a chronology of Wolf’s life compiled by his widow Lola Wolf and a 1949 commentary on Wolf’s career by German historian Richard Benz (1884-1966).

Once again I want to encourage readers to first go to my first Gustav Wolf blog for excerpts from Lola Wolf’s timeline of her husband’s life from birth up to 1908 when he cut the original ten Confessio blocks. Also, there’s no way for me to describe how striking are the prints from that portfolio. It’s better to see them as a group and one by one in my first Wolf post. (LINK) That post also provide full translations of Wolf’s mystical texts.

Zehn Holzschnitte: Background

Lola Wolf’s chronology offers little about the years surrounding the creation of Zehn Holschnitten.

But I like her description on the woodcuts: “Fantasy monsters, decorative in the foot-steps of the Art Nouveau style. Printed on Japan paper.”

Perhaps these small paintings by Wolf (note the trident-shape “W” monogram) were done during his 1912 journeys in Cairo and Jerusalem. Also, Firn has written to me: “I suspect they were done on the trip that Lola refers to.”

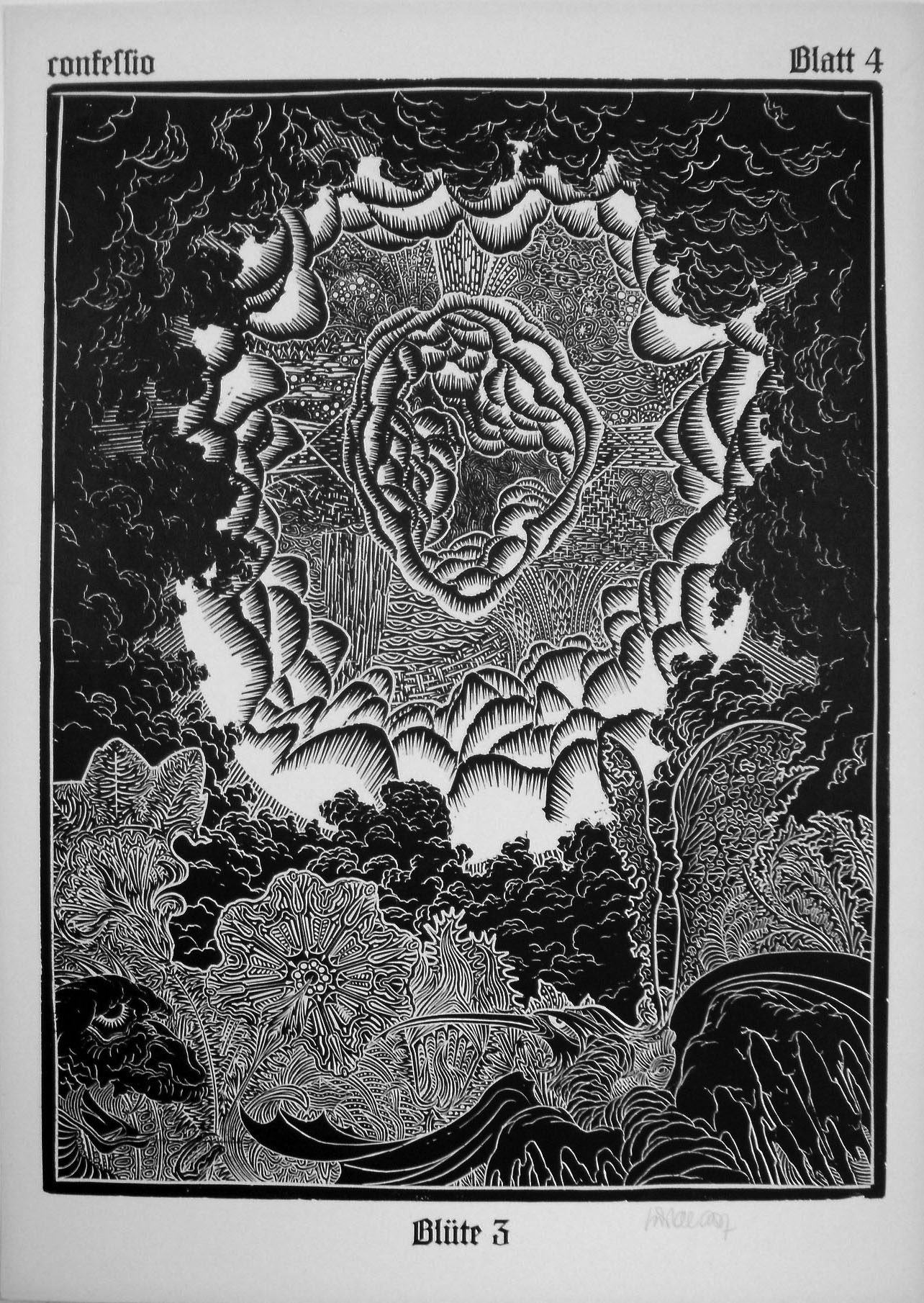

“Fantasy monsters,” as Lola Wolf calls them, are the sole subject of each of the ten prints in Zehn Holzschnitte.

Johann Eckart von Borries in his book on Gustav Wolf noted that monsters made first appearance in the fourth sheet in Confessio.

He wrote: “Among the few representational allusions within the Confessio sequence, fragments of fantastic animals can be seen on the third sheet of the flower sequence: on the left, a kind of dog’s head, on the right, a winged creature with a long, pointed tongue. They belong to a fantastic bestiary of its own that Wolf began to invent around this time and expanded over the years: bizarre dragons and snakes, flying and swimming animals, hybrid creatures, such as reptiles and insects, and similar imaginary creatures, which on the whole seem more grotesque than demonic.

“His second series of woodcuts is dedicated to them, which was published in 1911 by the Karlsruhe publishing house ‘Verlag der Quelle,’ under the neutral title ‘Ten Woodcuts.’ Wolf used a technique here that would only appear twice in his later work: he used two printing blocks for each sheet, one with the actual depiction in black and a second in various delicate shades for the mostly ornamented background. In the patterns of these grounds, as well as in the shape of some monsters, one can see the inspiring effect of East Asian models.

“These fantasy creatures also reappear among his early etchings, alongside imaginary landscapes and souvenir sheets from his trip to Cairo and Jerusalem at the beginning of 1912.”

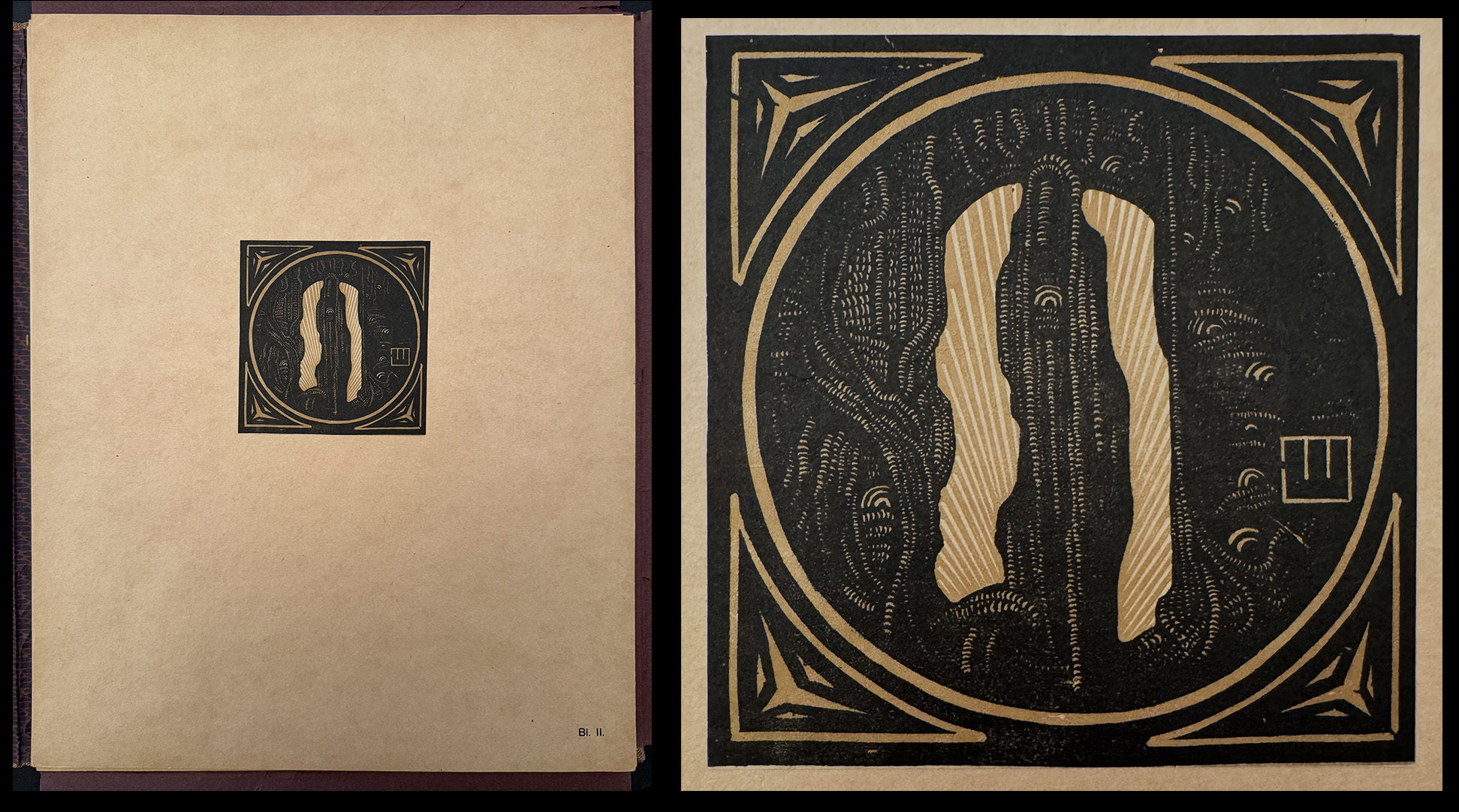

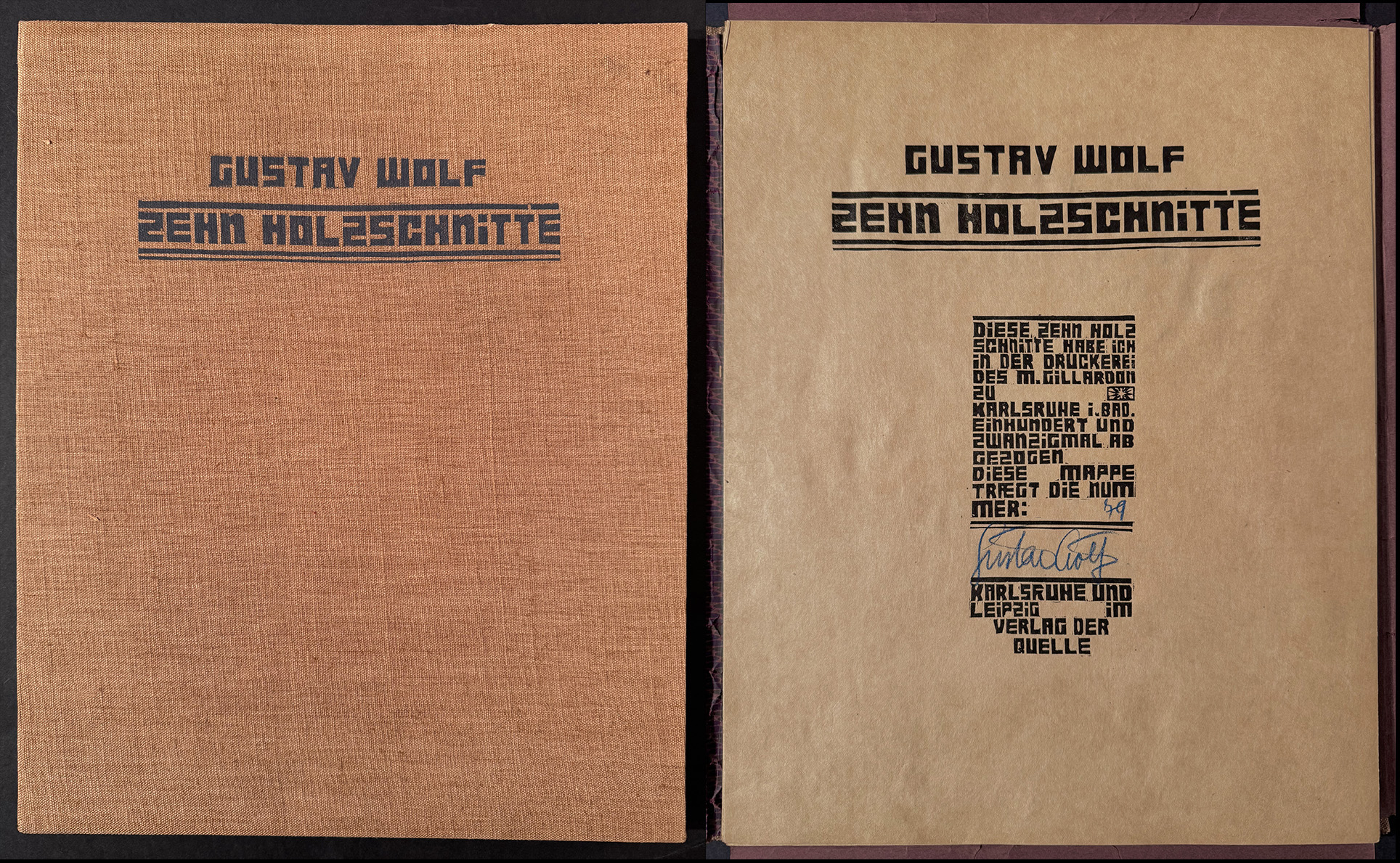

The portfolio cover (L) and colophon page for “Zehn Holzschnitte.” The sheet measures: 15 1/4″ x 12″ (38.7 x 30.5 cm)

The colophon indicated that Wolf had 120 copies of the 10 woodcuts made in the printshop of M. Gillardon in Karlsruhe and that this folder (“Mappe”) carries the number 79 (in my copy), below which is Wolf’s signature.

Zehn Holschnitte: the prints

The text in the upper left before Wolf’s name and the date in Roman numerals of 1910 is hard to decipher because of the lack of spacing, but I think the wording is: “All die tausend fael Tigegestalt ist das Wort des lebendigen Dranges das Deichen des Geistes der Unenlichkeit.” The translation would be: “All the thousand falsified forms is the word of the living urge, the sign of the spirit of infinity.”

All of the woodcuts in this portfolio are tipped onto a stiff parchment brown paper. By far this first woodcut at 9 3/4″ x 8 15/16″ (24.9 x 20 cm) is the largest. But like all others prints it was created from two blocks, one for a subtle color and one for black.

I suspect that by using two blocks for each print that Wolf was referencing chiaroscuro woodcut prints of the German and Italian Renaissance. His two blocks provided a mid-tone in a muted color and a detailed image thanks to a black–or “key”–plate. And he created a third color by leaving some of the image free of impression from the other two blocks. This allowed some of the color of the paper upon which the image was made to show through. Traditionally these areas are said to be “paper white,” regardless of the actual color of the paper. Renaissance printmakers would ofter use paper white to create highlights and help give three dimensions to the images in the print.

For example here is a detail from “Poet and the Siren,” a 1537 woodcut by an anonymous Venetian artist based on a drawing by Titian (Tiziano Vecellio). Note how the paper color creates hightlights to the hair and musculature to the back and shoulder.

However, at least in his first print Wolf does not utilize the color block and the paper color to create a sense of three dimensions. For instsnce, the dragon in this image is composed of just the tone block and the key block without any paper color showing through. This lack of paper white highlight fails to bring out a third dimension.

Here is the second woodcut. The image on the left shows its size compared to the full portfolio sheet: 15 1/4″ x 12″ (38.7 x 30.5 cm). Its measurements are just 3 15/16″ x 3 13/16″ (9.9 x 9.7 cm). Once again the reserved paper color is not used to define a third dimension, in this case to suggest rays of the sun.

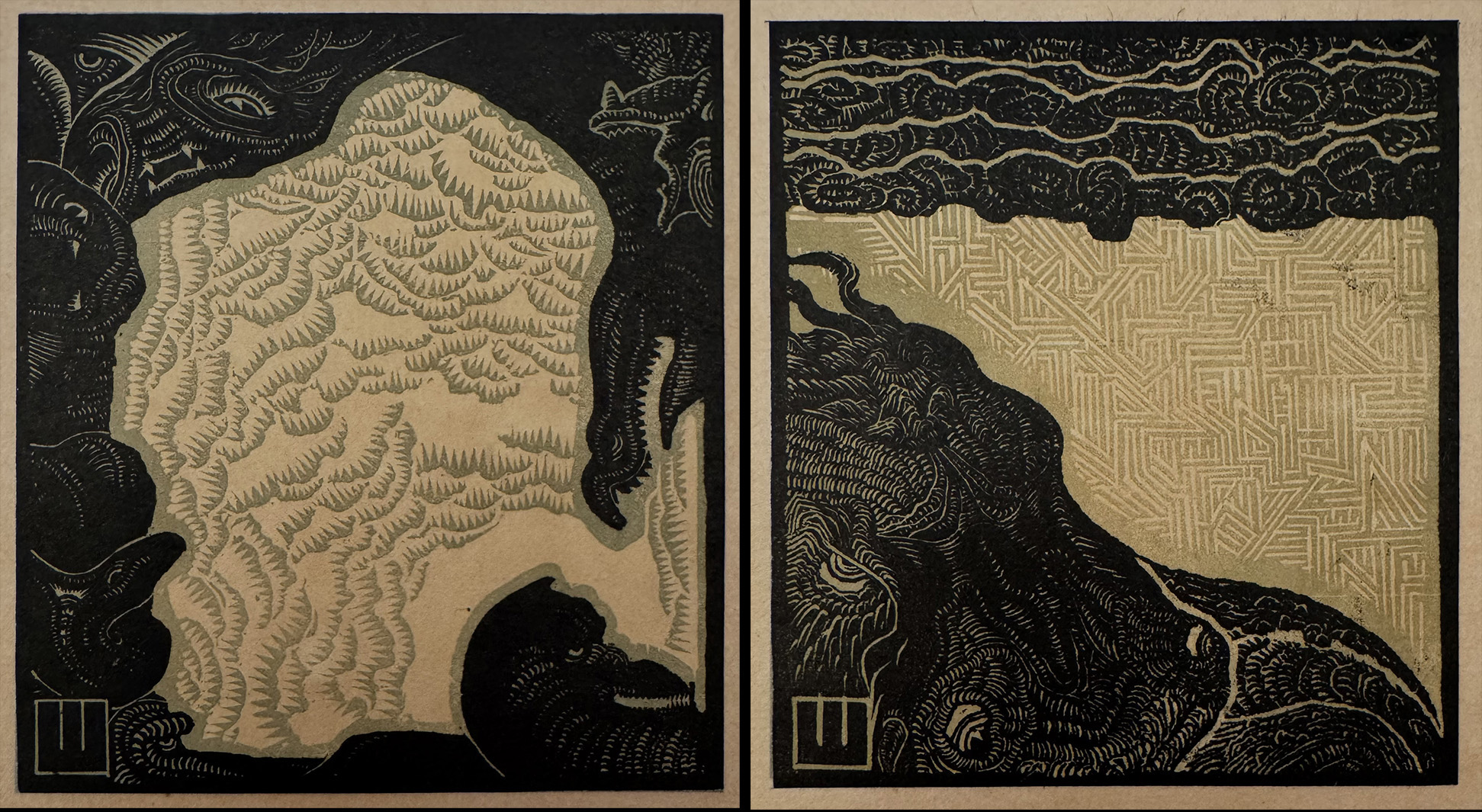

In Plates 3 and 4 the tone plate again is used to decorate the background, not to define the figures which are coming out of the periphery and edging closer to the center.

Thinking about Wolf’s choice of printing on a thin translucent Japan paper and his use of the paper color as an active color element to his designs, I wondered about his choice to mount the prints on a buff colored paper. It definitely muted the strength of the paper white.

To test this out I photographed Plate 3 after slipping a piece of white copy paper half way up from the bottom. You can plainly see how much brighter the paper color is when the white paper is behind it.

In Plates 5 and 6 the creatures take center stage. Again the chiaroscuro effect is missing. In Plates 4 and 5 the background pattern of an intermeshing groups of parallel lines is very similar to the what Wolf used in two years earlier Confessio, particularly in its last plate.

Finally in Plate 7 (left) Gustav Wolf used the paper color in the spirit of Renaissance chiaroscuro. The paper color provided highlights and the colored block created a mid-tone. Together with the key (black) block, the horned critter has a hint of three dimensions.

Not surprisingly I immediately thought of Albrecht Dürer’s rhinoceros woodcut of 1515. But here’s the head of the rhino as interpreted in 1620 by Dutchman Willem Janis Blaeu in chiaroscuro.

In Plate 8 Wolf reserved the paper white for the white of the eye and slashes in the background. This monster was a variation of the “dog” (as von Borries called it) in the lower left of fourth plate in Confessio. (See above)

The background in Plate 9 is the most delicate of the series. It’s in strong contrast to the monster with its gaping mouth. Like in Plate 5 the tone block is limited to the background.

In the last plate Gustav Wolf created a full chiaroscuro, with paper white joining the tone block to add dimension to his creature. However, on viewing Plate 10 online I had trouble seeing what was there. The pair of pointed objects in the center I saw as the back of ears, perhaps from the head of a fox. But nothing else in the image confirmed that assumption. Not until I had my copy of Zehn Holzschnitte in hand did those projections read as lower teeth in a wide-open mouth. Only then did I recognize an eye near the top left corner.

Once I came to that visualization, I started to see a sequence in the nine small images. In Plate 2 eyes blink awake from the walls of a cave-like structure. Wolf’s creatures become more readable in Plates 2, 3 and 4. Not until Plates 5 and 6 do his beings take center stage. In Plates 7, 8 and 9 they become more and more threatening. Then in Plate 10 the monster is ready to swallow up the viewer.

Next UP

✪ ✪ ✪

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/gustav-wolf-his-monster-menagerie/trackback/