Gustav Wolf: Confessio

INTRoduction

Ever since 2015 when the Baltimore Museum of Art acquired a copy of the Welt, a portfolio of woodcuts by Gustav Wolf, 1887-1947, I’ve been smitten by this German artist’s work. So much so that I subsequently acquired six portfolios of his work. I also got a copy of “Gustav Wolf: Das Druckgraphische Werk (The Graphic Work),” the 1982 catalogue raisonné of Wolf’s prints by Johann Eckart von Borries. The trouble was I couldn’t get the book’s German text translated.

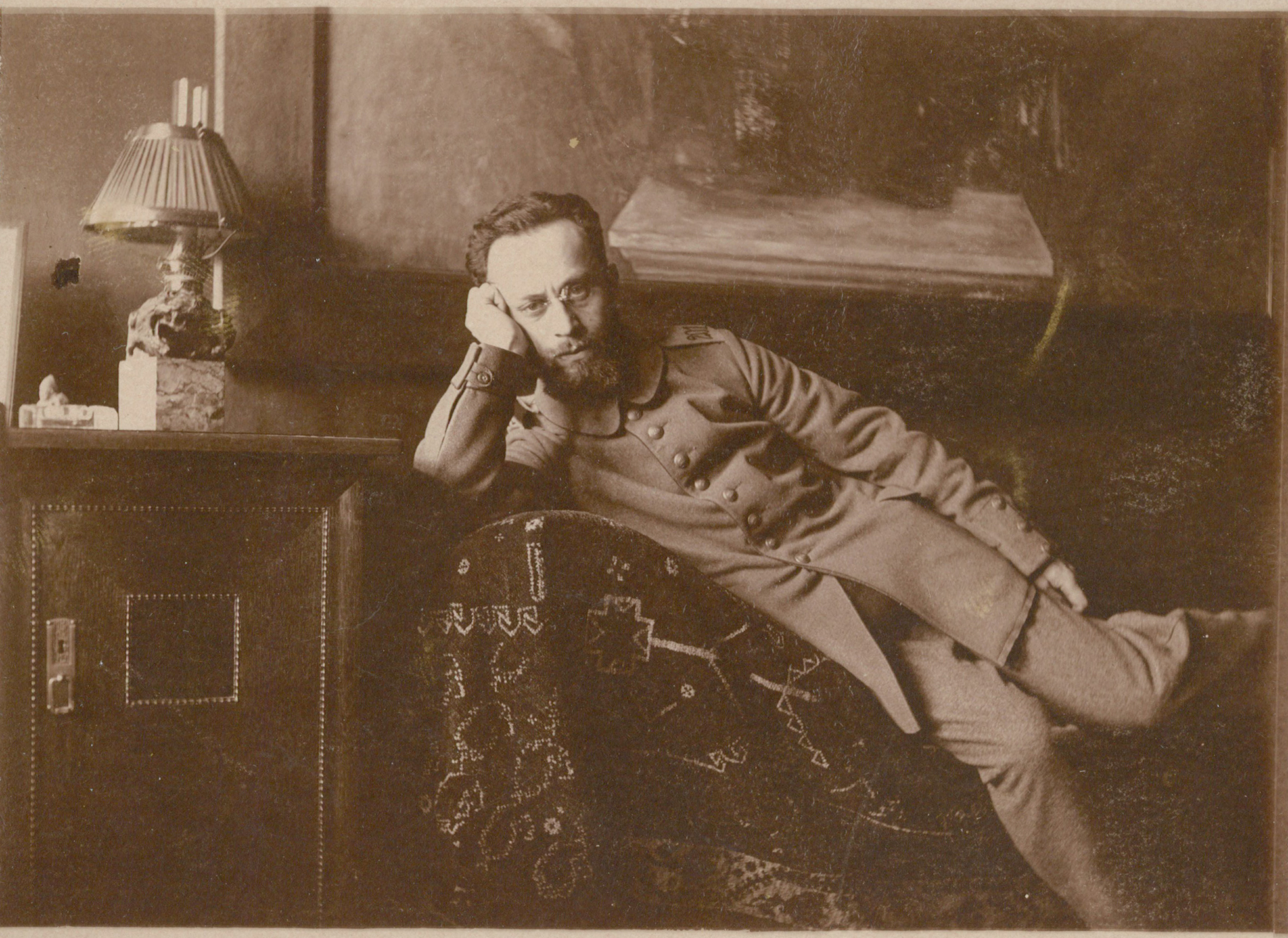

Then last October (2023) I was contacted by Leigh Firn, who wrote: “I came across your blog while I was researching Gustav Wolf. He was my great uncle (my grandfather’s younger brother). I was happy to see that you enjoyed his work. In the event that you are interested in a little more background about him I’d be happy to share with you what I have.” Firn subsequently sent me photos of Wolf, images of some of his paintings and prints, as well as chronology of Wolf’s life compiled by his widow Lola Wolf and a 1949 commentary on Wolf’s career by German historian Richard Benz (1884-1966), who had written about Wolf as early as 1922 and in 1924-5 was co-editor with Wolf on the cultural periodical “Pforte Blätter.”

This past winter when I started to contact Maryland museums about eventually accessing some of my print collection, I didn’t suspect that I’d meet a translator for the von Borries book. But when I found out that Daniel Fulco, the Agnita M. Stine Schreiber Curator at the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts in Hagerstown, had studied in Germany, I couldn’t help myself and asked if he would help me. Not only did he translate the von Borries essay but he also translated what three persons wrote about their memories of the artist, included in this book.

Then to the rescue came Frank Thiemicke, the German print dealer who sold me Confessio last year. When I contacted him recently to say I was about to start a series of Gustav Wolf blog posts, he took it upon himself to translate Confessio texts.

In short, I now have so much stuff on Wolf that I need to write separate ART I SEE posts on each of the six Wolf portfolios that I have. And I’ll start chronologically with Confessio: Worte und Zeichen (Confession: Words and Signs), which he created in 1908-9 but it was not published until 1922. And with each post I’ll present some of the timeline that his widow assembled.

I’ll also try to sketch a description of the artist and his personality.

All images of Wolf’s artwork as well as family photos are presented courtesy of the Estate of Gustav Wolf.

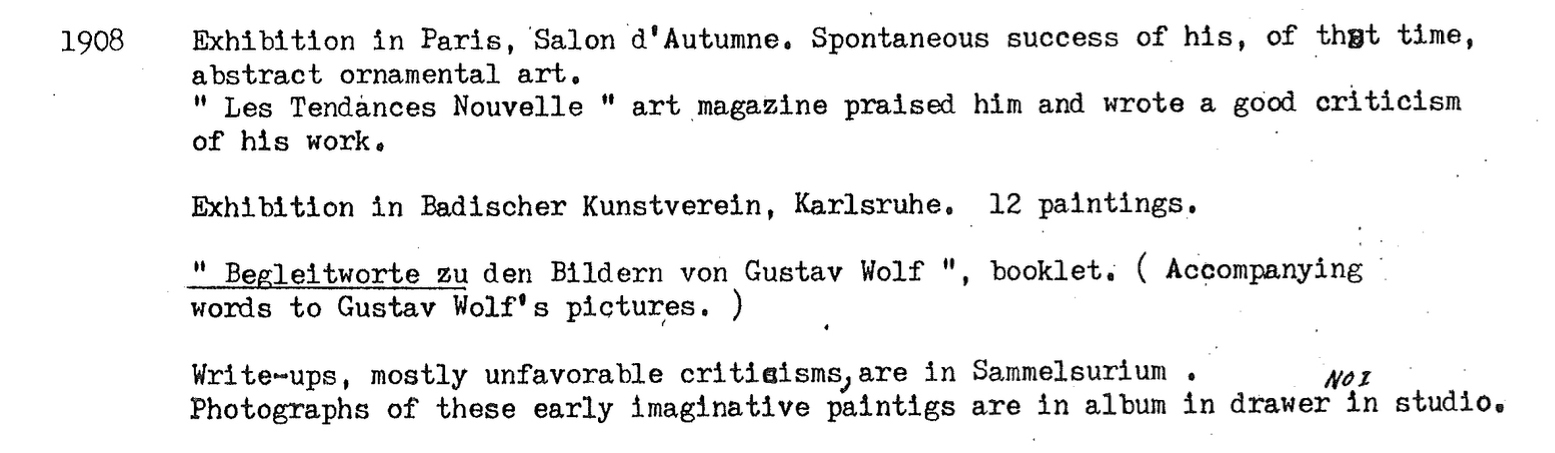

Timeline up to 1908

Thanks to Lola Wolf, I can share a chronological timeline of her husband’s life. Excerpts from her timeline appear with a white background.

It begins with her noting the fount of information Gustav left behind in his “Sammelsurium,” which sort of translates as a hodgepodge or conglomeration of things.

Gustav Wolf was born on June 26, 1887 in Östringen, Baden near Bruchsal, Germany. He appeared to have had a very normal upbringing and was allowed to study painting at an early age thanks to his mother reaching out to painter Hans Thoma.

His life was comfortable enough for him to travel widely as a young man and paint copies of Old Masters.

In 1906 or 1907 he had his first exhibition “probably” in Munich, where a local newspaper wrote that Wolf was a diabolic painter. Lola Wolf wrote: “The art critics were bewildered and wrote unfavorably of his, for that time, very strange work.”

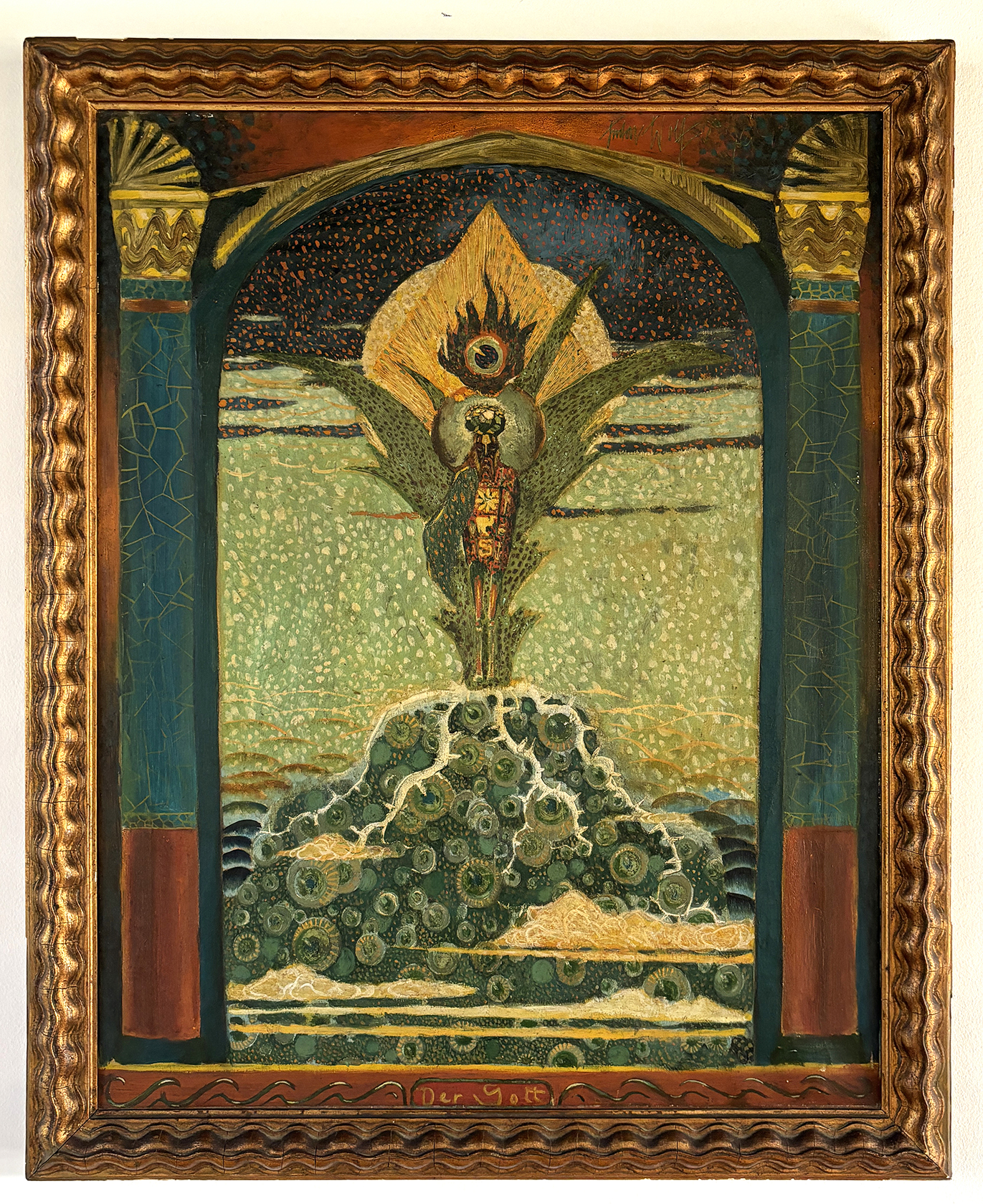

I believe that this Gustav Wolf painting “Der Gott” is from 1907. Perhaps this is what critics thought of as “very strange.”

1908 appears to have been a breakthrough year. His “abstract ornamental art” was exhibited at Salon d’Autumne in Paris and the art magazine Les Tendances Nouvelle praised his work. He also showed paintings in Karlsruhe, Germany. But Lola Wolf also noted that “mostly unfavorable criticisms”occurred in 1908.

From the perspective of this blog post, the most important development was Wolf’s creation of the 12 woodcuts that comprise Confessio. His widow listed the medium as “wood-engravings,” but both the large scale of the work and the visible tool marks appear to indicate that Gustav cut onto planks of wood (creating woodcut) not the ingrain of wood (creating wood engravings).

His widow wrote that Confessio wasn’t published until 1918, Johann Eckart von Borries in his book puts its publication date as 1922.

The colophon for “Confessio” indicates that there was an edition of 250 signed by the artist. This copy was not numbered. The publisher was Eugen Diederichs, Jena, Germany.

Confessio: the structure

As to Wolf’s studies at the School for applied Arts in Karlsruhe, Johann Eckartvon Borries wrote: “He may have learned the technique of lithography or etching there, but he obviously taught himself how to cut wood, which is so important for his artistic expression.”

Von Borries then stated: “He himself was obviously well aware that the black and white art of graphics particularly suited his talent. As early as 1908, he noted that for him “color only serves to contribute to the harmony of the whole, to support the lines in their role as carriers of the pictorial idea.”

While teaching at the Karlsruhe Art Academy briefly in the 1920s, Wolf wrote about the importance of woodcutting for an artist (as presented in the von Borries book): “He voluntarily accepts the compulsion to be simple, to concentrate, to be clear and to concentrate his strengths. Instead of the talkative pen, he takes the taciturn knife. Instead of the patient paper, the brittle woodblock, so that the spark can fly again from the battle of the spirit with the matter…”

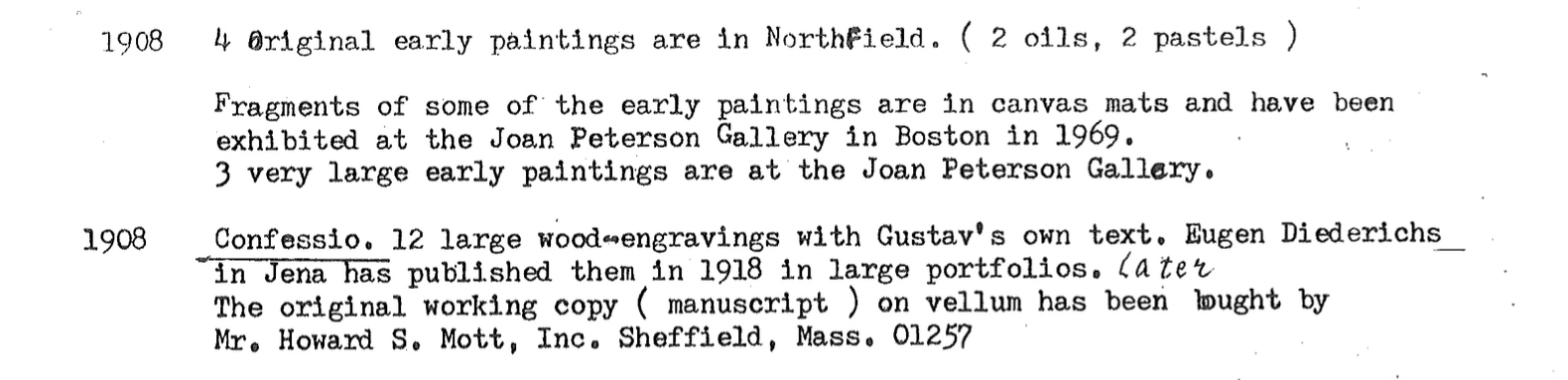

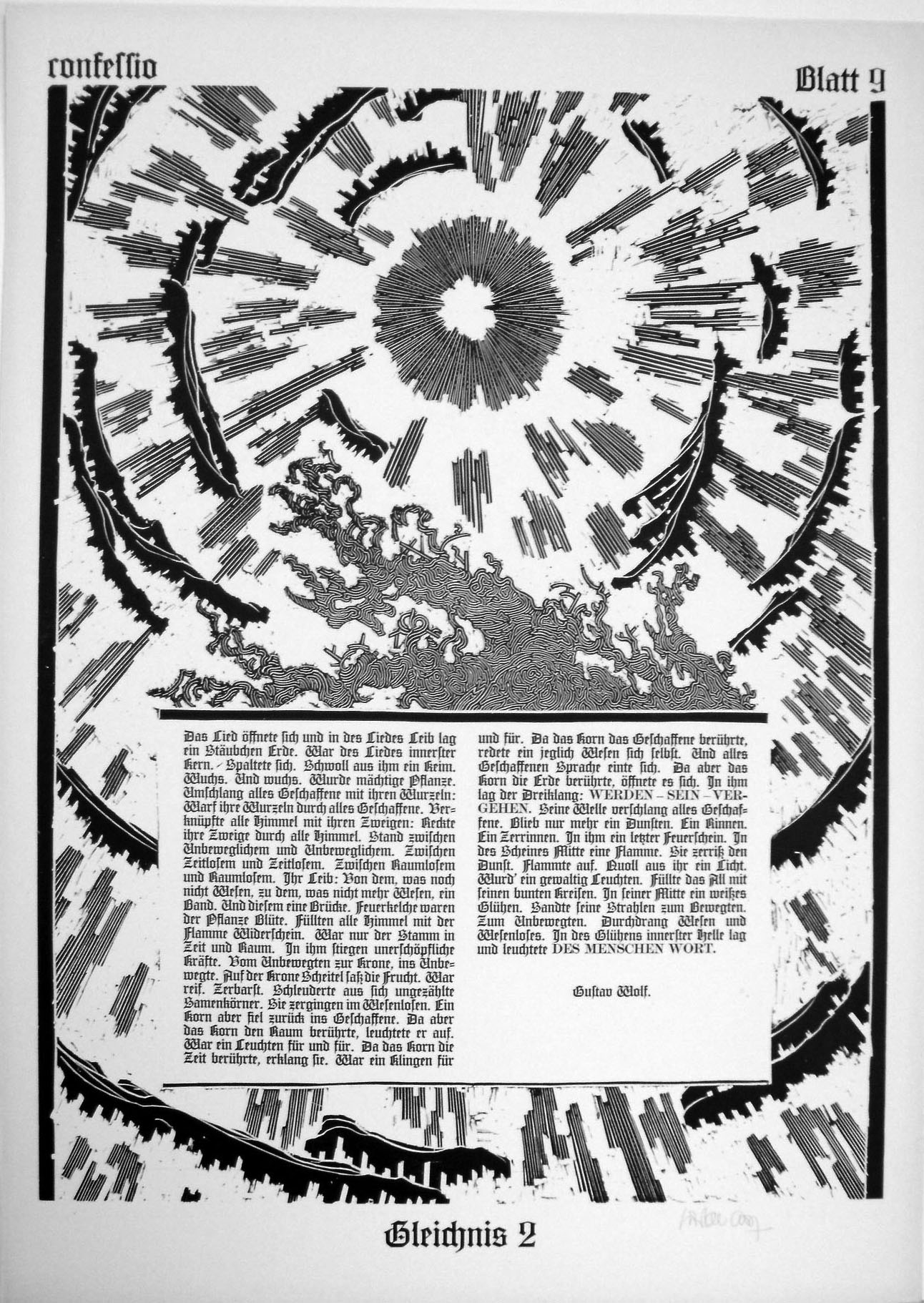

In Confessio not only did Wolf display a dazzling woodcut technique but he incorporated his own mystical thoughts by cutting out rectangles in seven of the eleven blocks. Wolf used these spaces inserting text set in letterpress for an introduction and three short essays.

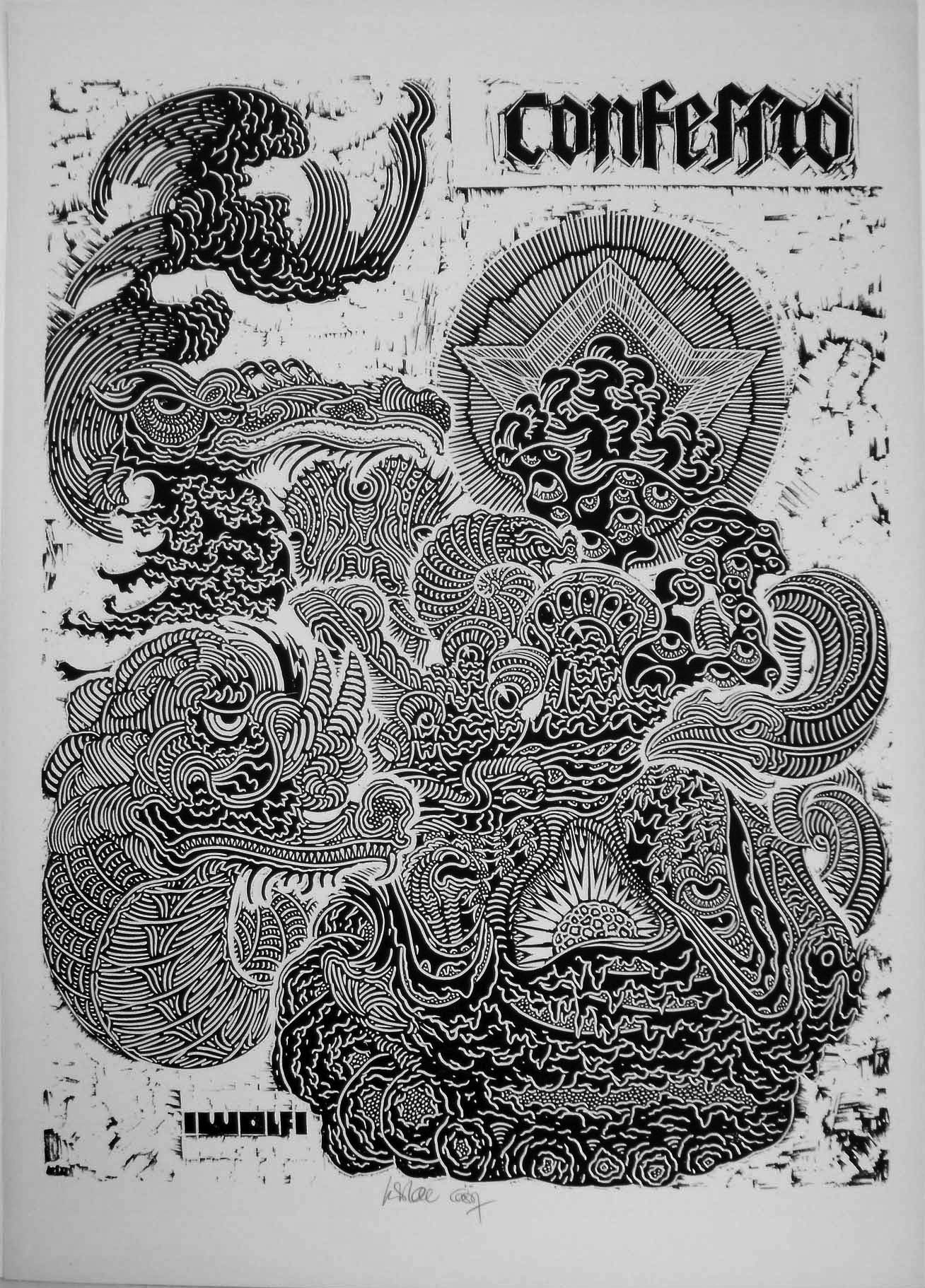

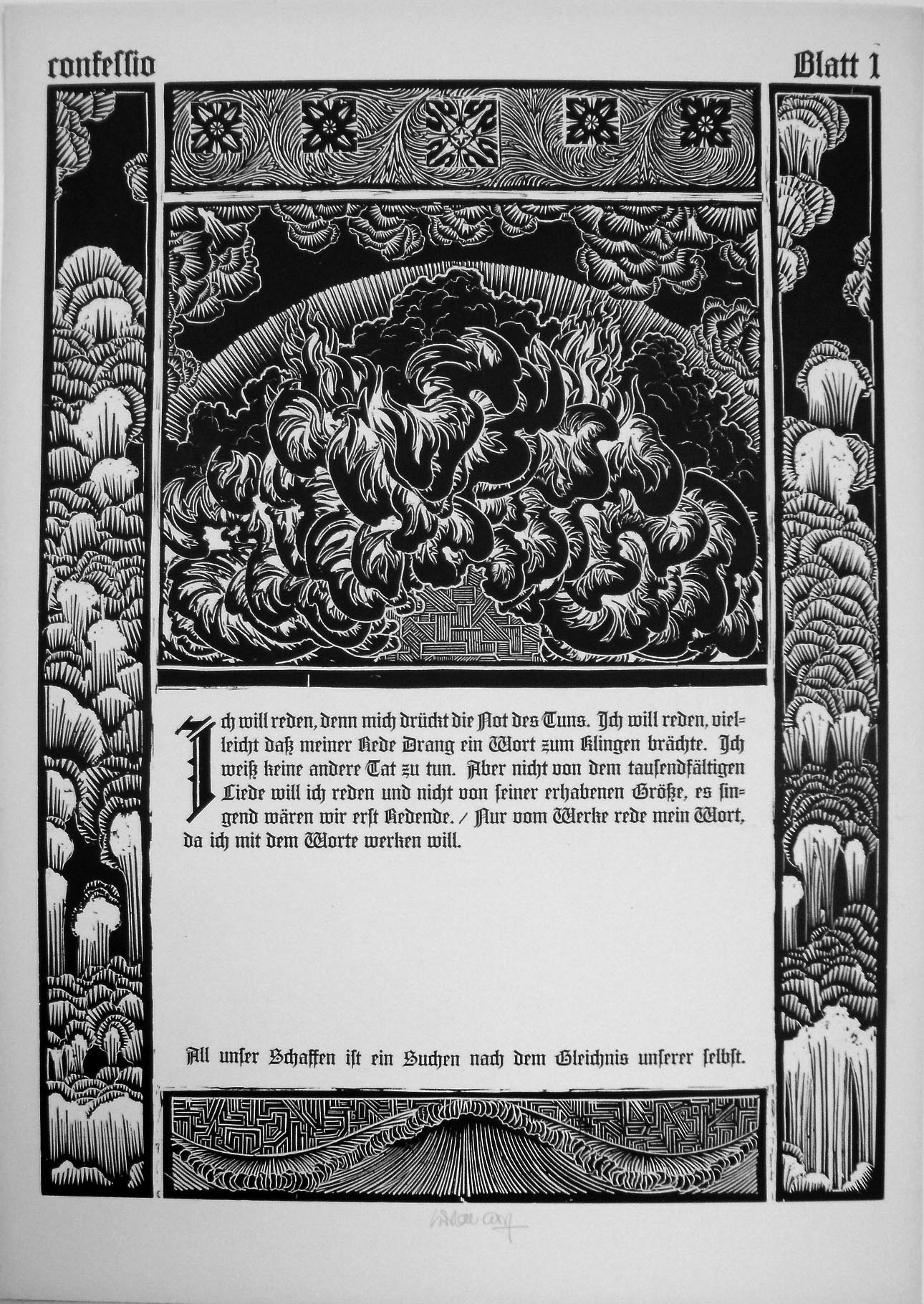

Von Borries wrote: “The first series of woodcuts that the artist created in 1908-09, after he had quickly acquired a perfect cutting technique, is entitled ‘Confessio, Words and Signs.’ In this ‘confession’ of profound mystical insights, image and word are closely linked compositionally.” He indicated that early proofs with hand-written text left the context between image and text rather loose, that the relationship became clearer in the 1922 published version by Eugen Diedrich in Jena, Germany.

According to von Borries, this title page was not created until the portfolio was about to be published in 1922. All sheets in this portfolio are pencil signed and measure 27.5″ x 19.75″ (69.85 x 50.16 cm)

“What is astonishing for a first work, in addition to the inventive wealth,” wrote von Borries, “is the decisiveness and certainty of the delivery. This is where you would most likely see the effects of studying at applied arts school.”

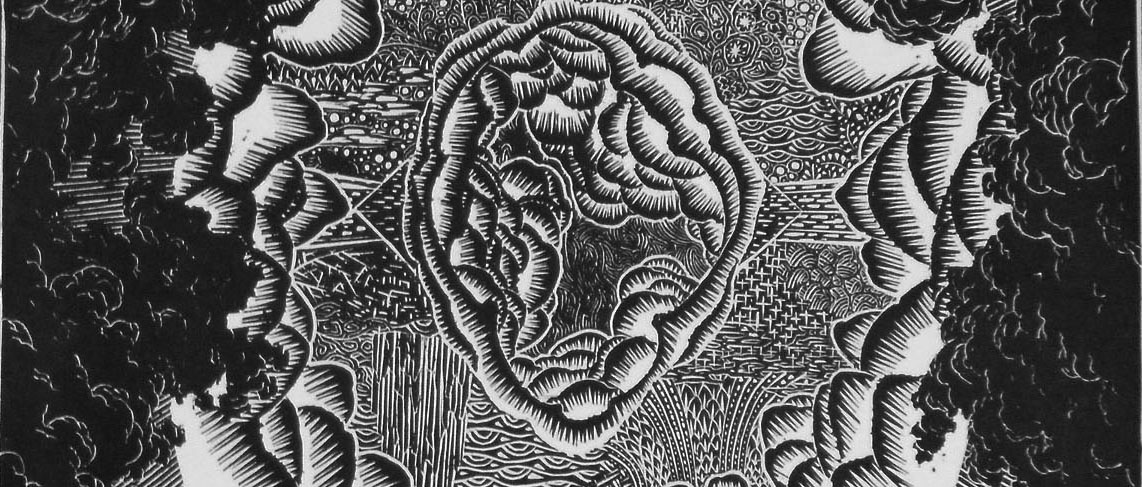

In his assessment, von Borries wrote: “Formally, the ‘Confessio’ woodcuts are clearly rooted in Art Nouveau. Certainly, Gustav Wolf was a resolute loner all his life, not bound to any school or belonging to any group. But he too, at least in his early days, could not escape the style of his time. The choice of woodcarving technique and its material-appropriate handling, which was understood as an ethical obligation, are the legacy of the stylistic movement; as well as the inclusion of writing in the overall composition of a leaf. Above all, however, it shows the distinctive impact of Art Nouveau in the highly abstract, ornamental formal language. The basic element is the line: the black one on a light background primarily has a shape-forming function, while the white one usually serves to structure dark areas. They form oscillating-dynamic and angular-static lineaments that overlap, penetrate, or strictly separate from one another. This creates dense patterns in which the surface element predominates, while physical and spatial elements are only hinted at in places. Often-used oriental and Far Eastern suggestions give the compositions their own charm of fairytale strangeness and delicacy.”

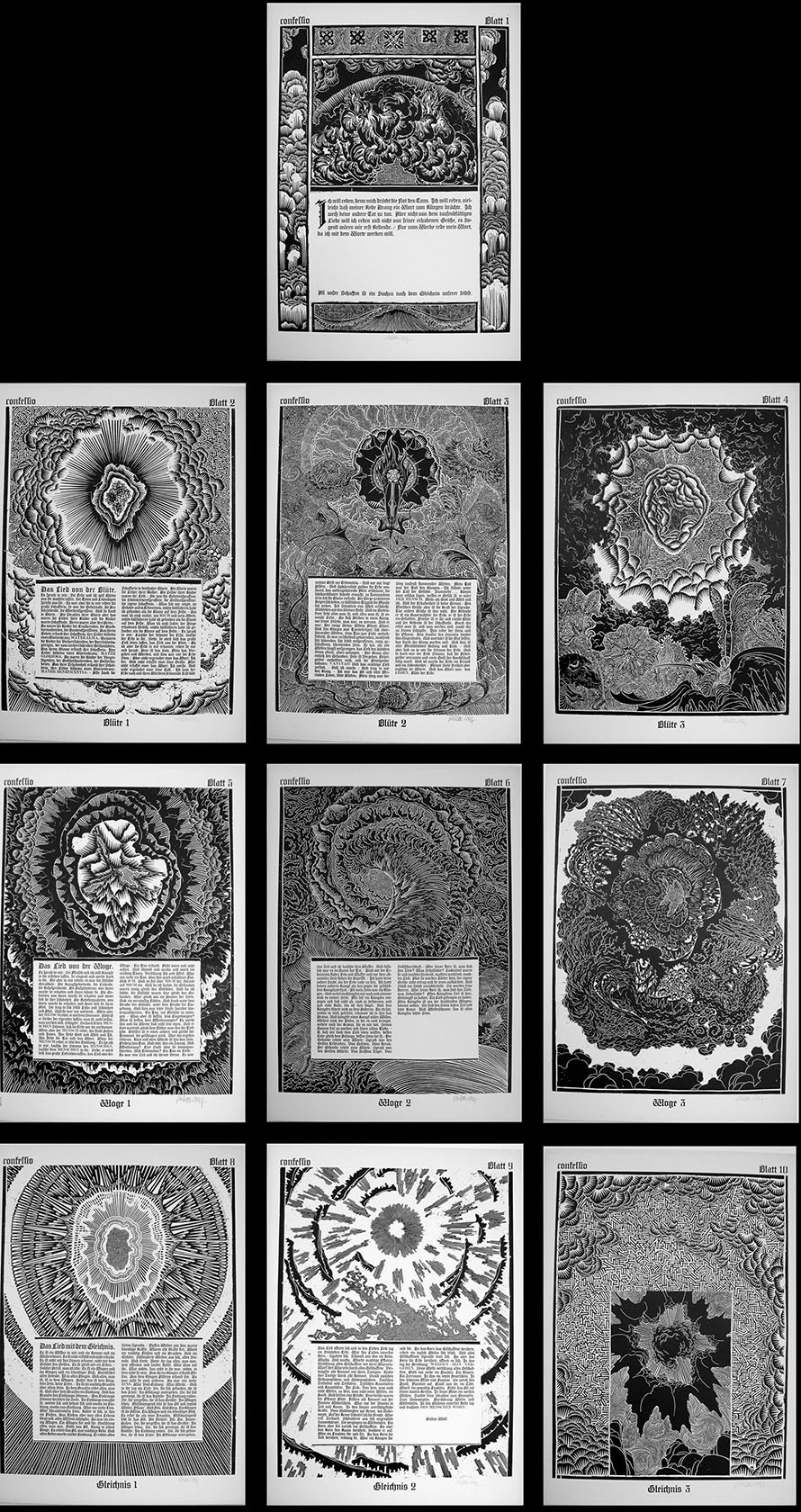

In the 1908 conception of “Confessio,” it began with the introduction sheet followed by the triads of three sheets each.

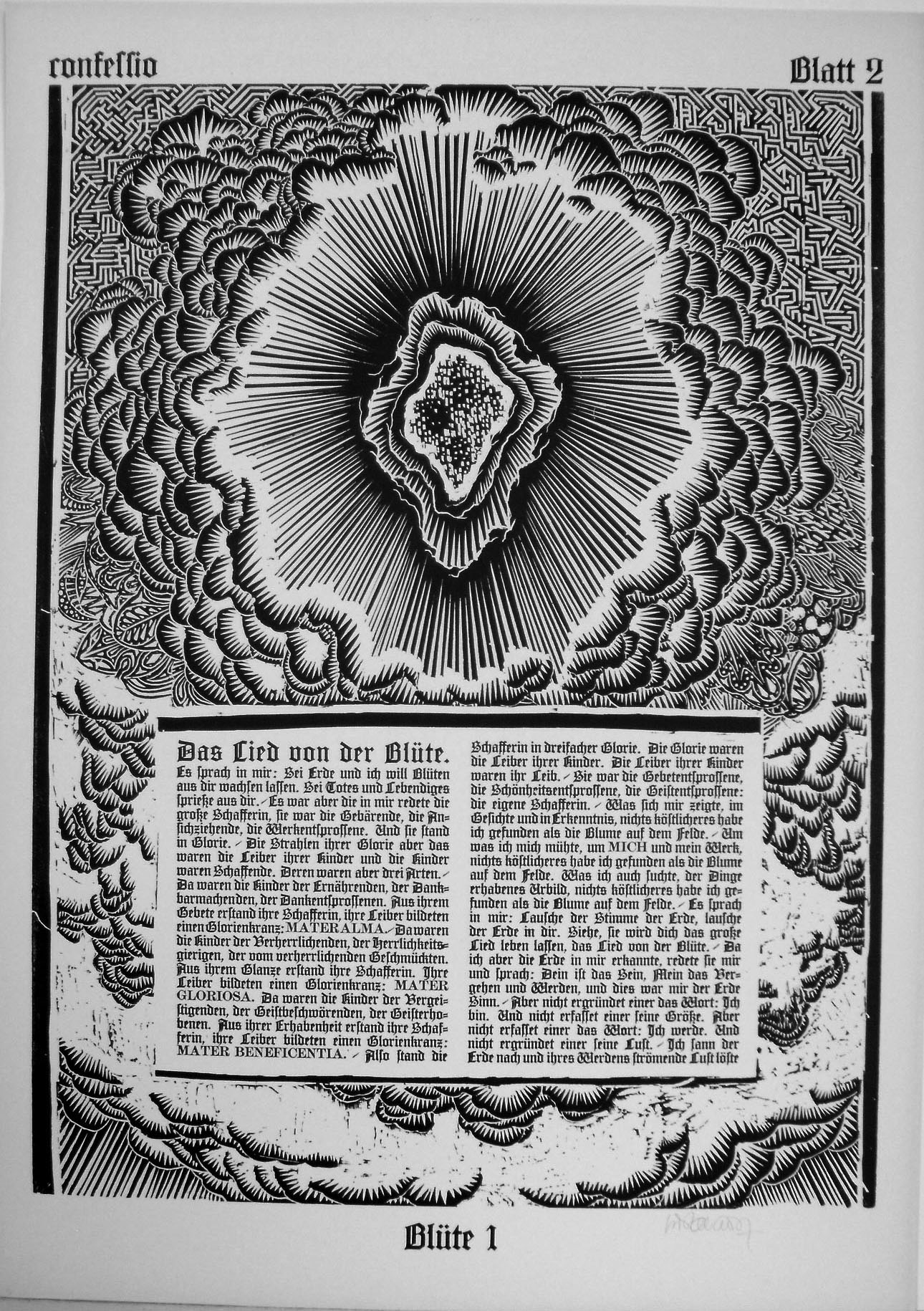

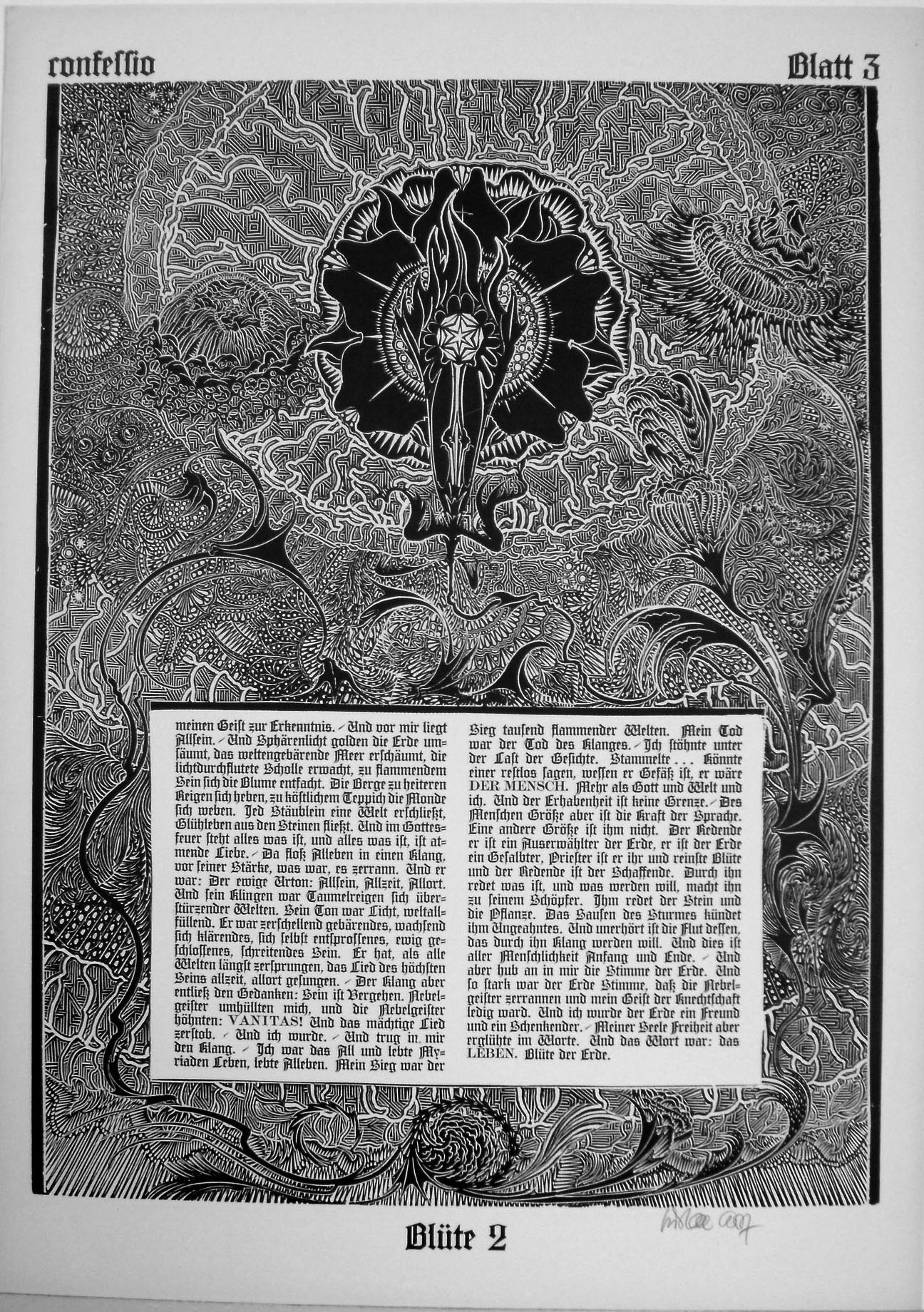

As to the sequencing of Confessio portfolio, von Borries wrote: “If one ignores the originally non-existent title woodcut, there is an introductory sheet depicting swirling flames, with an introductory text and three groups of three compositions each. At the beginning of each triad, there is the image of an amorphous structure emitting rays, which Wolf explained in a later publication as a sign of the ‘holy.’ ”

Each triad contains two sheets on combined text and image and concludes with a full-sheet woodcut.

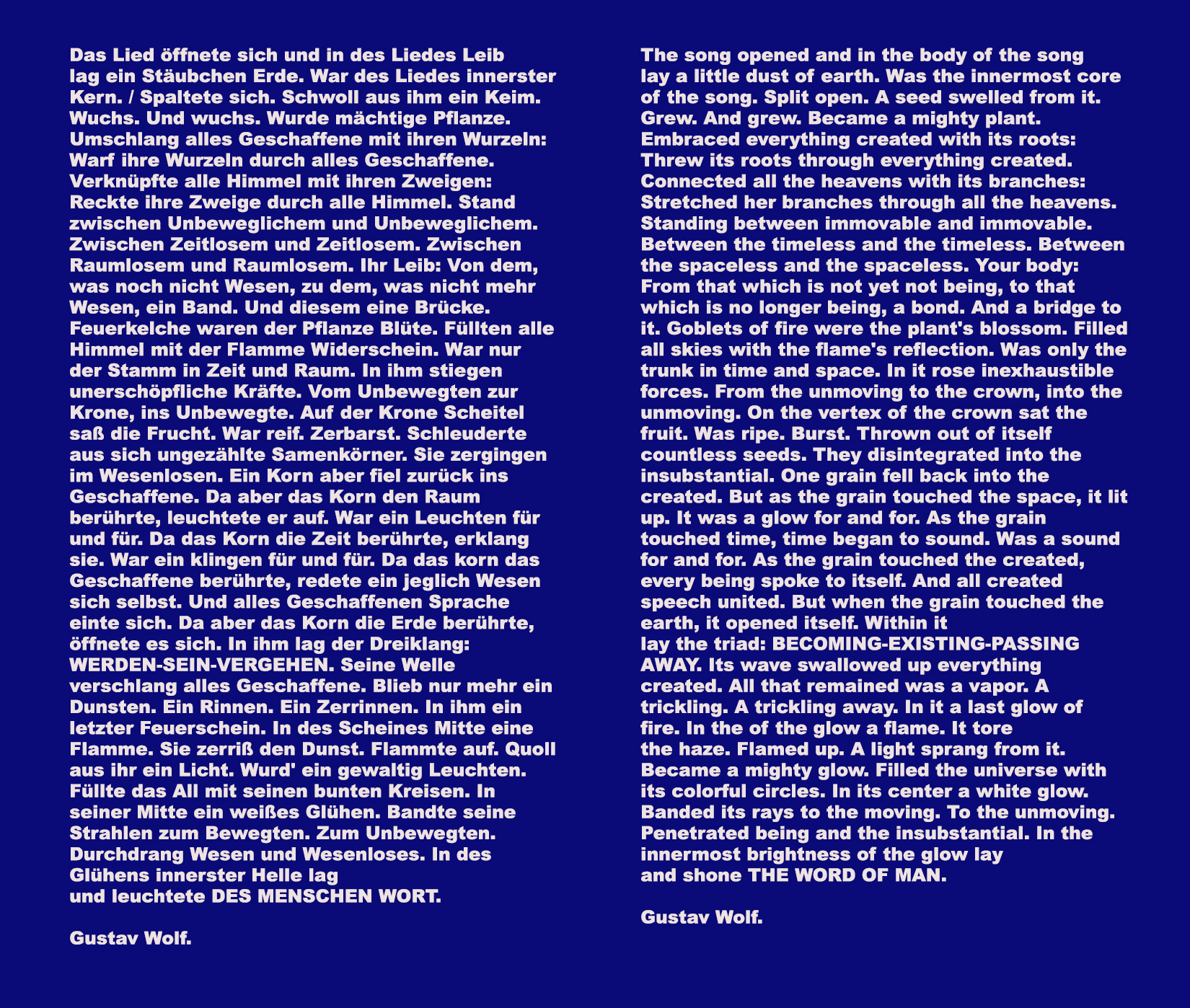

In his comments on Wolf’s woodcuts, von Borries wrote: “On sheet 2 [first triad, first sheet], the rays push clouds apart; on sheet 5 [second triad, first sheet] they are threatened by darkness, while on sheet 8 [third triad, first sheet] they unfold freely. This alludes to the content of the respective text, which incidentally has echoes of Nietzsche’s language, and not just in the titles. The first group talks about life under the title ‘The Song of the Flower.’ The associated illustrations [first triad, second and third sheets] illustrate growth and flowering. What follows is ‘The Song of the Wave,’ which is about people and their struggles. Here [second triad, second and third sheets] huge waves and whirlpools appear. ‘The Song with the Parable’ finally sings the praise of ‘Triad: Becoming, Being, Passing Away,’ accompanied by depictions of passing (away) and dissolution [third triad, second and third sheets].”

Confessio: plates & text

Frank Thiemicke really liked the idea of my blogging on Wolf, saying in an August email: “An online blog (or whatever work) on all his portfolios is a great achievement for today’s collectors and further generations.” Then to my surprise he added: “Have you translations of the actual Confessio texts? Below is some quick attempt, again with online resources. I’m sure these bots can’t catch Wolf’s poetic words completely, but maybe it works as such for a start. I was surprised the online translater is able to recognize the old font without major faults. I did some slight corrections, both with the German text and the English translation.” He then included Wolf’s Confessio introduction in both German and English.

A few days later he sent me translations of all of Confessio saying: “Here is what I was able to do. The German texts are again online-converted, but almost entirely corrected by me, so you can work with these now. BUT I’m not sure what a native English speaker will think about the–in parts slightly corrected by me–online translations (to American English) if he’s able to fully understand/read the German poems as Wolf used some dated phrases/twisted words that might provoke space for interpretation and translation variants.”

Then to double check on Thiemicke’s translations, I forwarded them to Daniel Fulco, who translated von Borries texts. He responded: “I had a look at the translations you sent and they look fine. Since the text is quite poetic and written in a fragmentary style, some phrases seem a bit eccentric but that was Wolf’s intent.”

So Thiemicke’s translation follows, but please email me should you have any suggestions.

The first plate with introductory text.

So Gustav Wolf begins: “I want to speak, because the flood of doing weighs me down.”

This is the first plate of the first triad.

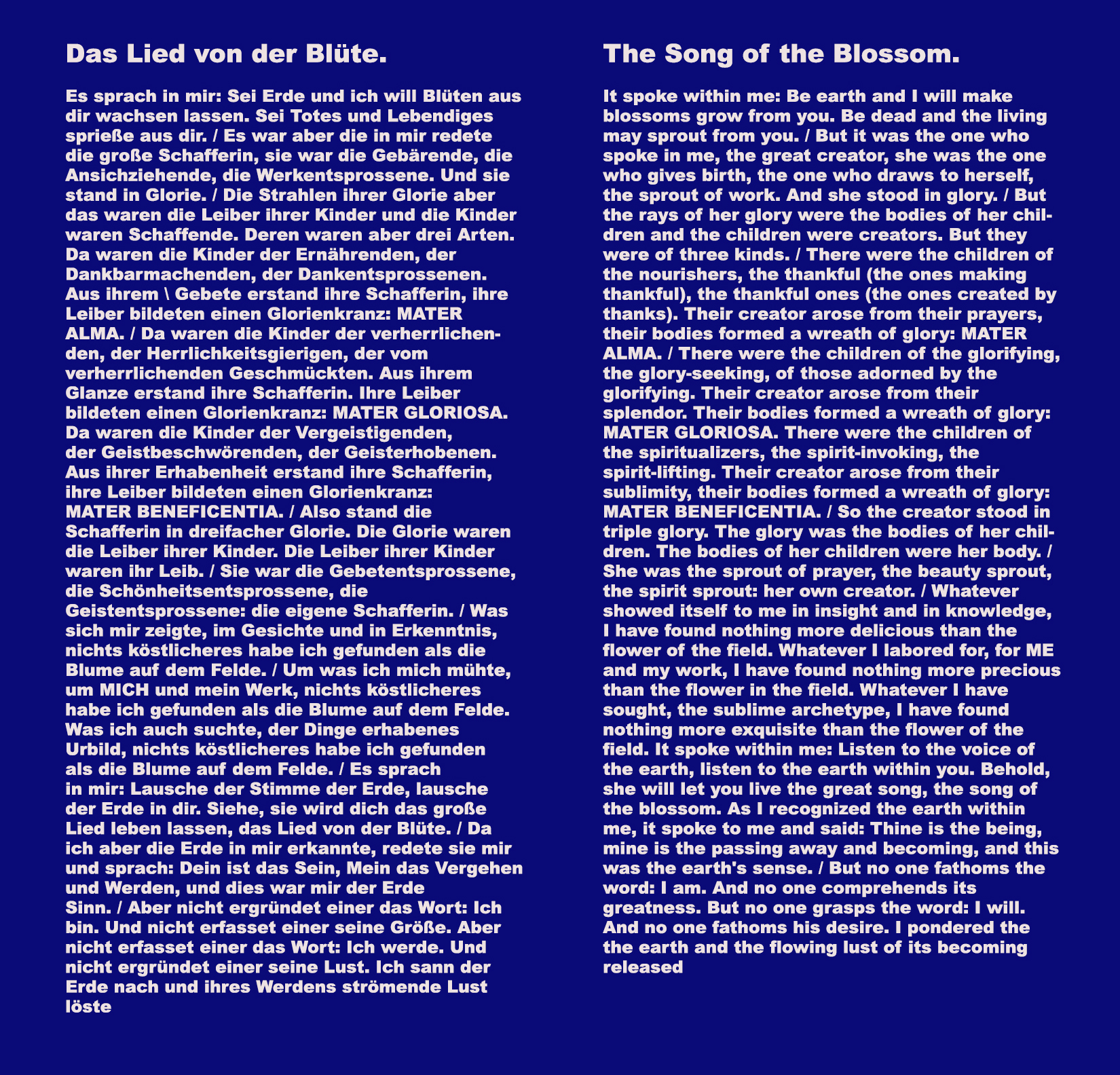

In the Song of the Blossom, Wolf began with another triad: children of the thankful, children of the glory-seeking and children of the spirit-lifting. He referred to the great creator as She. As a person and artist, Wolf saw himself in part among the children who are thankful. He wrote: “Whatever I labored for, for ME and my work, I have found nothing more precious than the flower in the field. Whatever I have sought, the sublime archetype, I have found nothing more exquisite than the flower of the field.”

The Song of the Blossom continued with Wolf in rhapsody: “The mountains rise to cheerful dance, the moons are woven. Each little stalk opens up a world, Glowing life flows from the stones. And in the fire of God stands all that is, and all that is, is breathing love.”

Then Wolf evoked the power of the word: “Man’s greatness is the power of speech. There is no other greatness for him. The speaker he is a chosen one of the earth, he is the earth’s anointed one, he is her priest and purest blossom and the Speaker is the Creator.” And Wolf the poet saw himself as the speaker: “But the voice of the earth began to sound in me. And so strong was the voice of the earth that the misty spirits melted away and my spirit of bondage became free.”

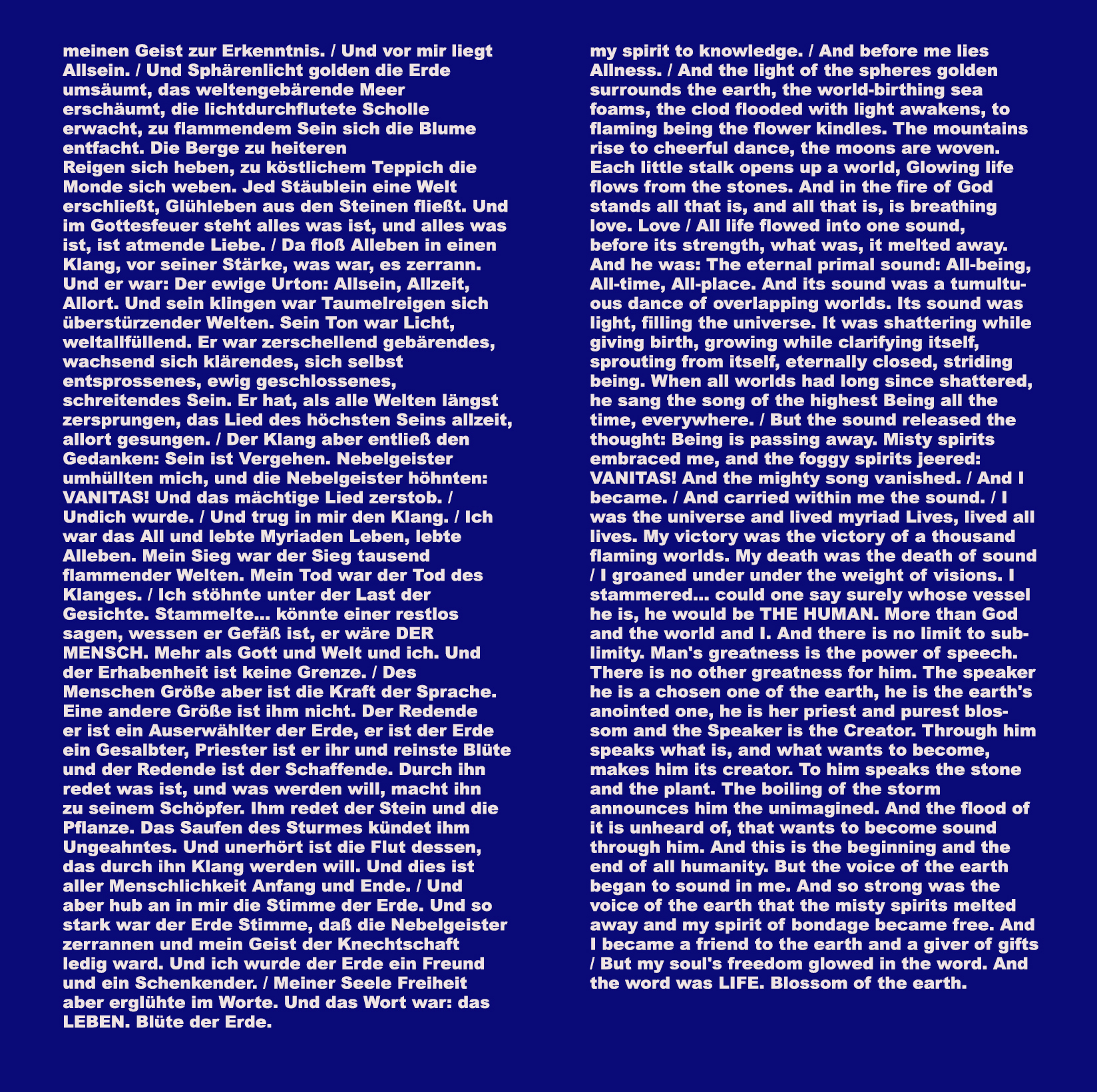

This is the second plate of the first triad.

This is the third plate of the first triad and is the only plate that von Borries wrote about: “Among the few representational allusions within the ‘Confessio’ sequence: on the left, a kind of dog’s head, on the right, a winged creature with a long, pointed tongue. They belong to a fantastic bestiary of its own that Wolf began to invent around this time and expanded over the years: bizarre dragons and snakes, flying and swimming animals, hybrid creatures, such as reptiles and insects, and similar imaginary creatures, which on the whole seem more grotesque than demonic.”

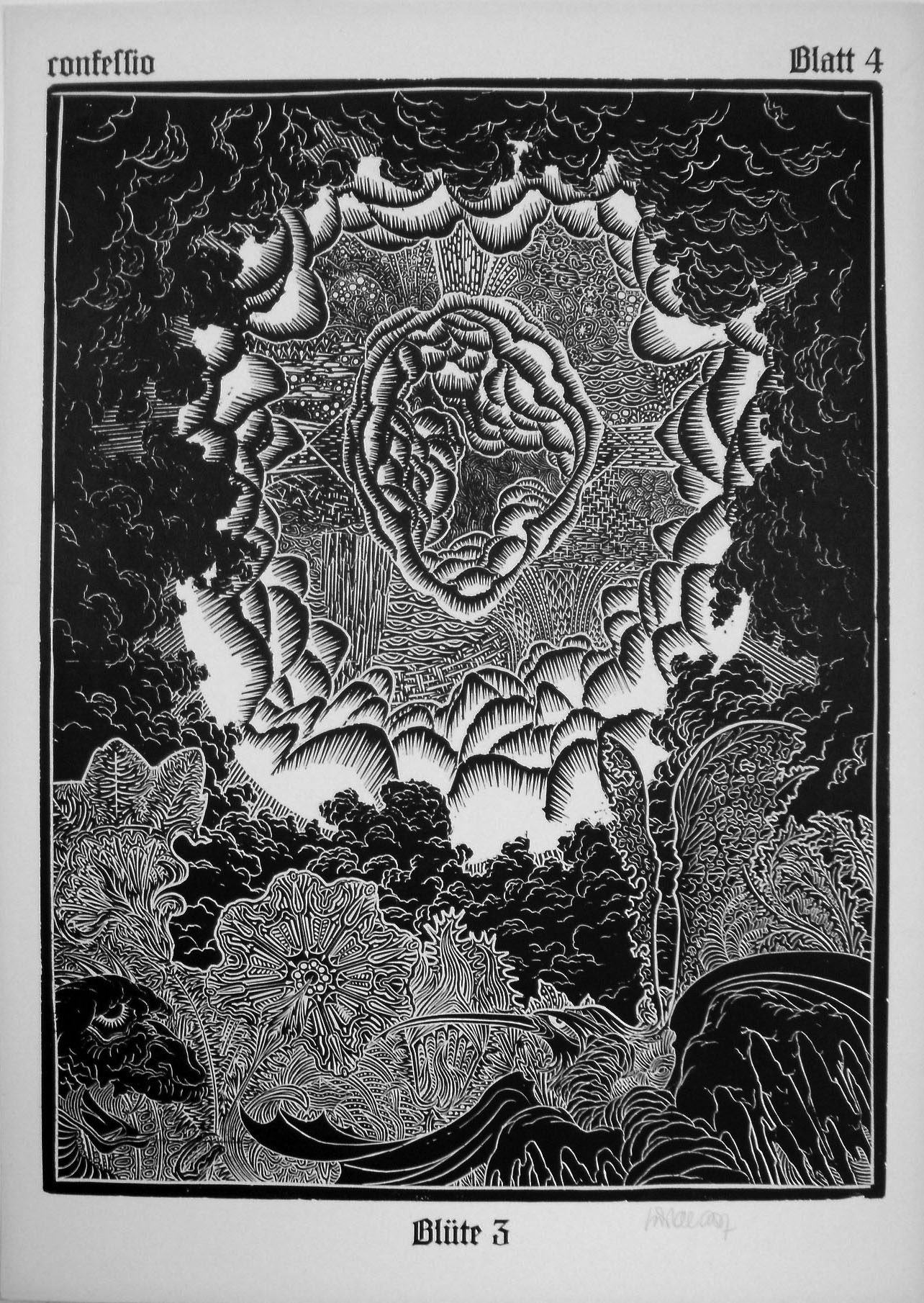

This is the first plate of the second triad.

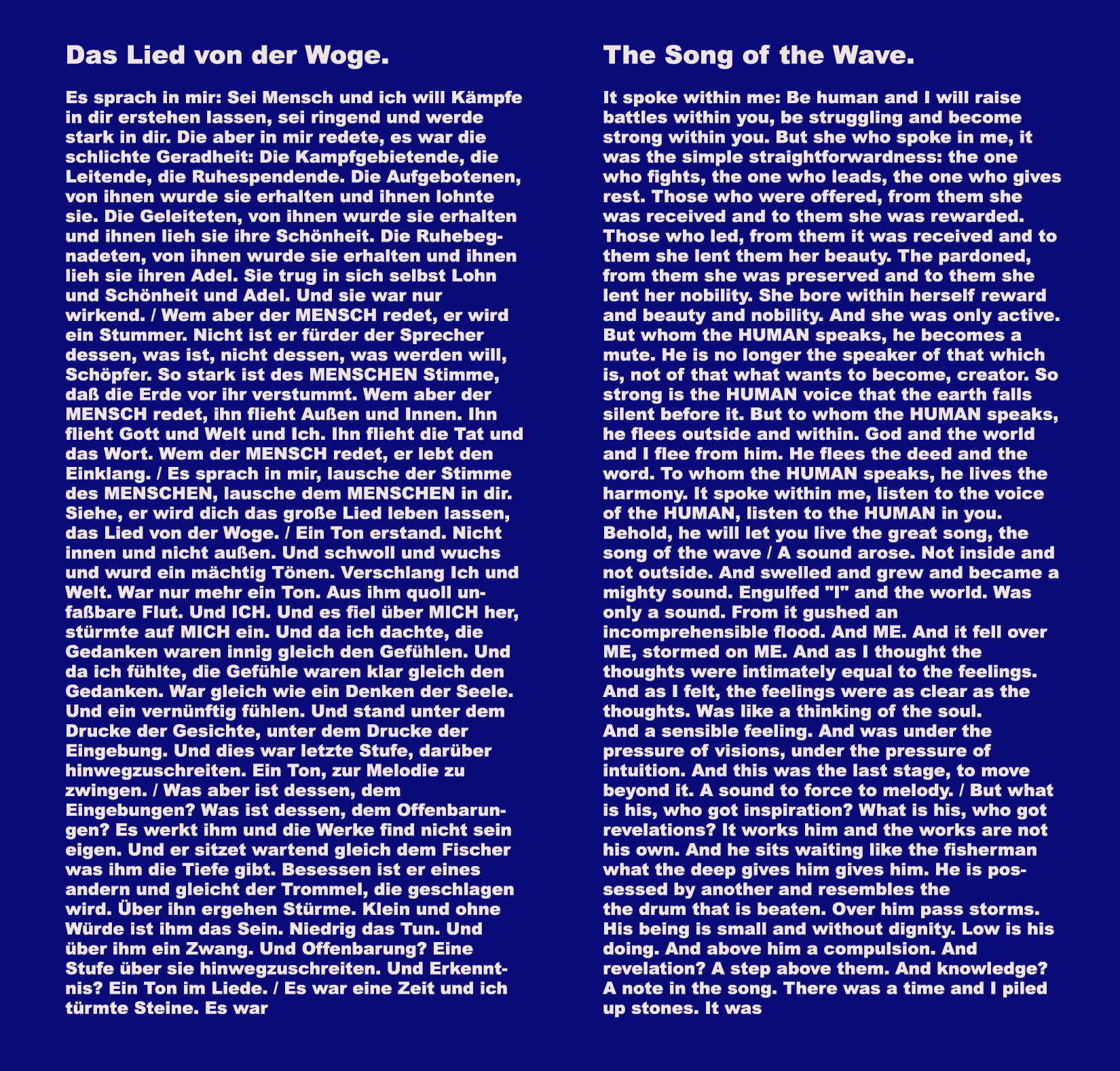

The Song of the Wave begins: “It spoke within me: Be human and I will raise battles within you, be struggling and become strong within you.” Again referring to the power of human speech, he wrote: “So strong is the HUMAN voice that the earth falls silent before it.” Wolf added: “To whom the HUMAN speaks, he lives the harmony. It spoke within me, listen to the voice of the HUMAN, listen to the HUMAN in you. Behold, he will let you live the great song, the song of the wave.” But the song overtook him: “And swelled and grew and became a mighty sound. Engulfed ‘I’ and the world. Was only a sound. From it gushed an incomprehensible flood.”

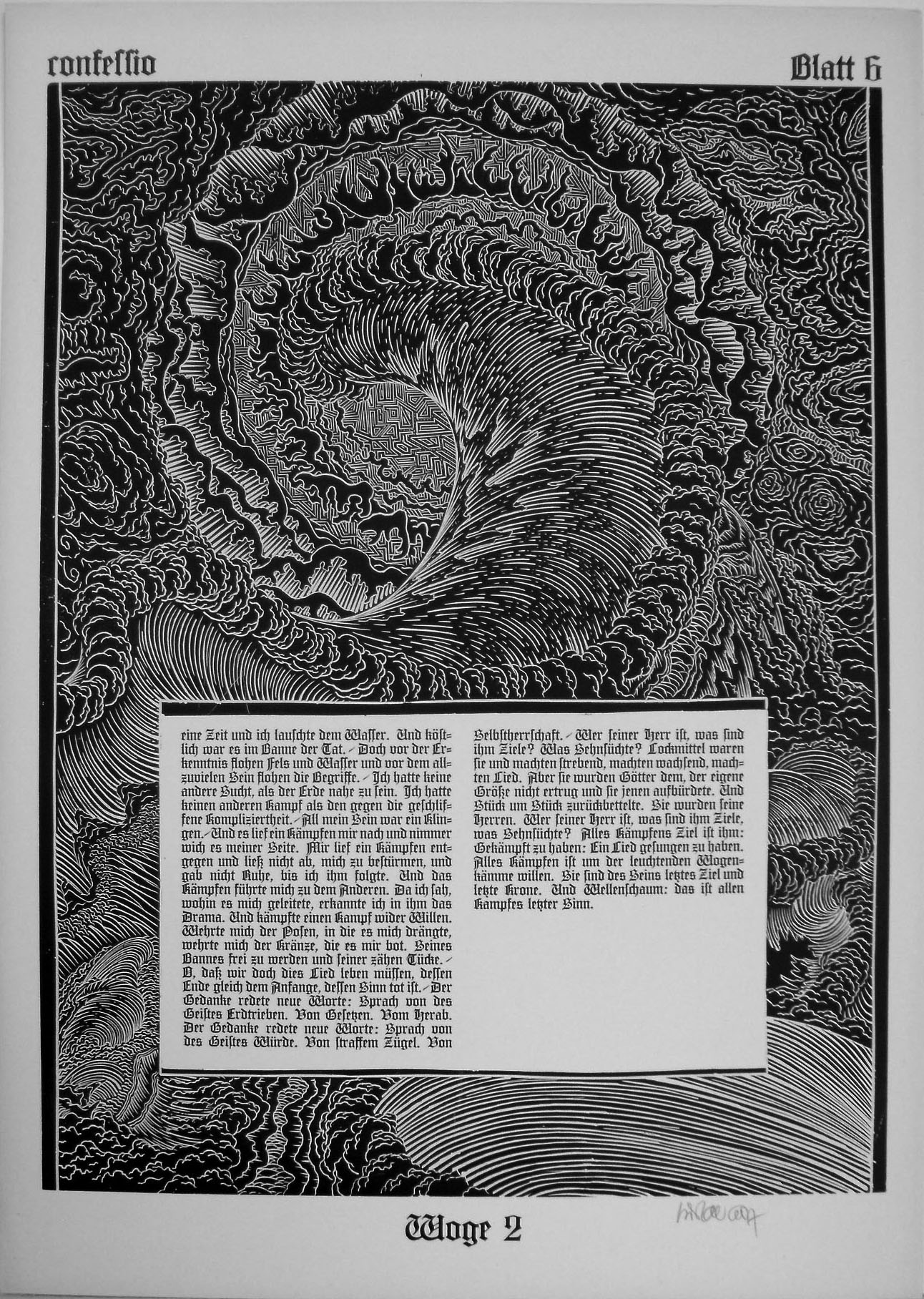

Then the Song of the Wave turns: “And a struggle ran after me and it never left my side. A struggle ran towards me and did not cease to assail me, and did not rest until I followed him…. I resisted the poses it forced me into, resisted the wreaths it offered me. To be free from its spell and its tenacious malice. Oh, that we must live this song, whose End like the beginning, whose meaning is dead.”

The struggle for Wolf appeared to be maintaining his independence of thought: “Who is his master, what are his goals? What are longings? They were lures and made striving, made growing, made song. But they became gods to those who could not stand greatness but imposed them on others. And begged them back piece by piece. They became his masters.” He concluded: “All fighting is for the sake of the shining crests of the waves. They are his ultimate goal and last crown.”

This is the second plate of the second triad.

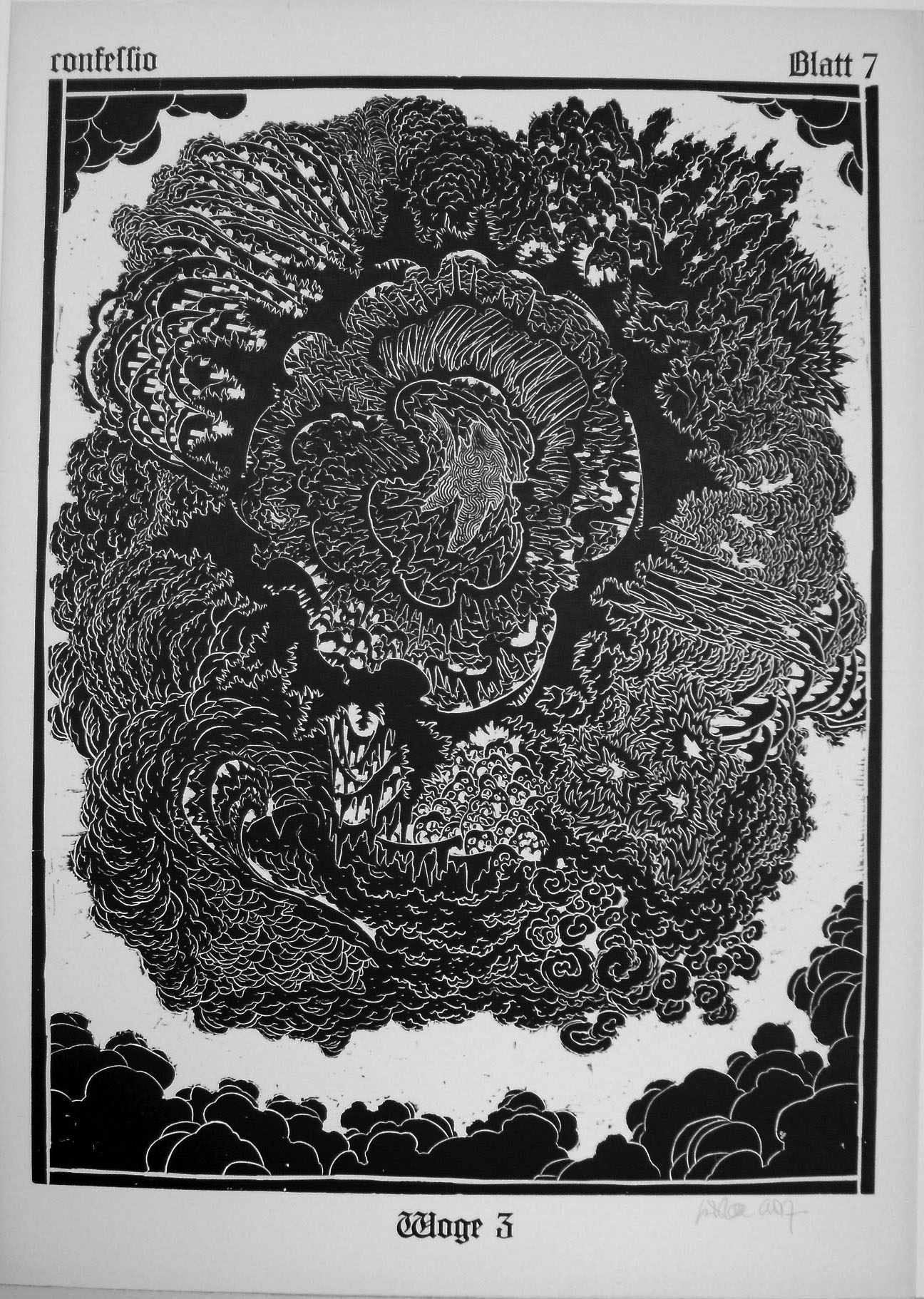

This is the third plate of the second triad.

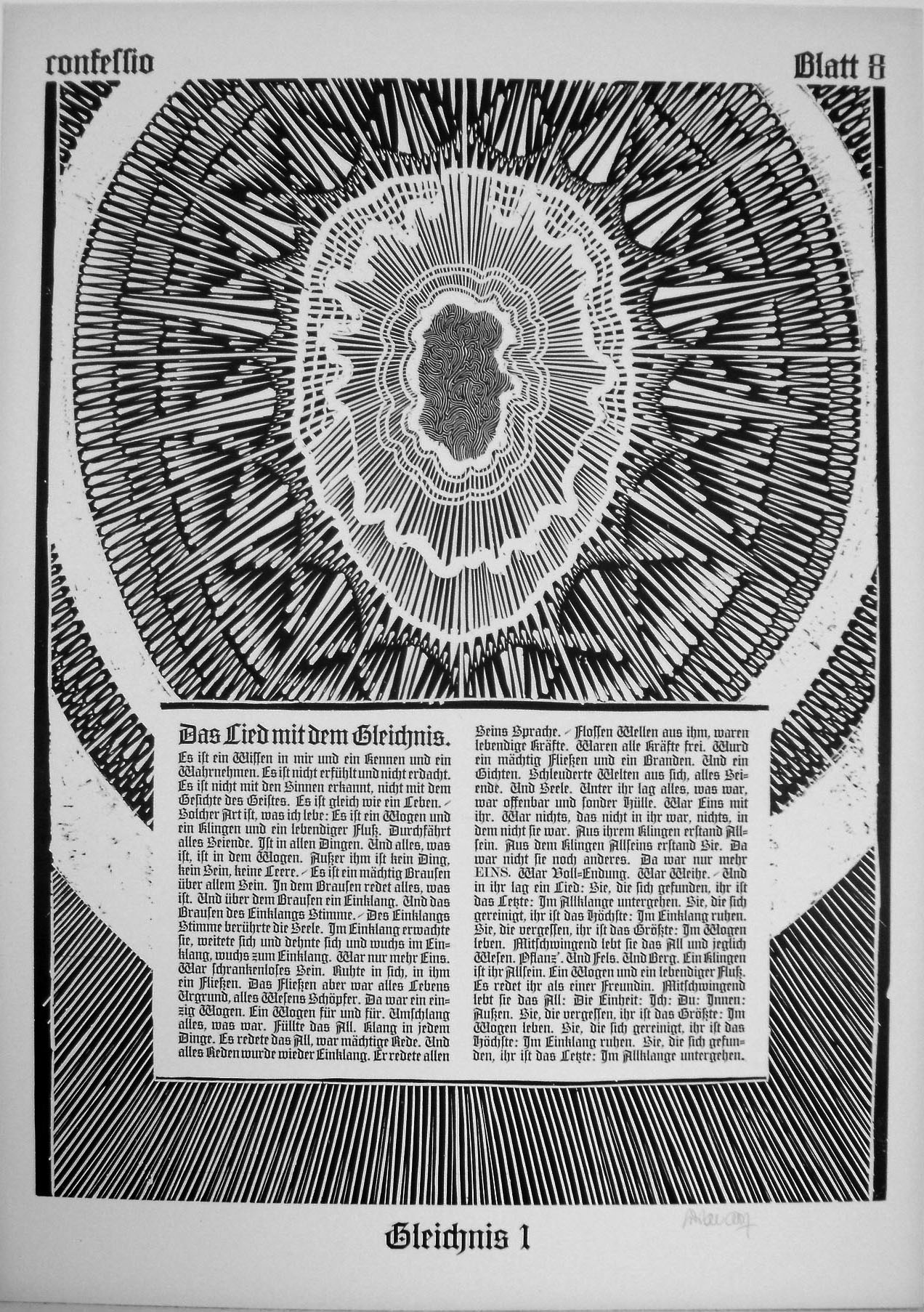

This is the first plate of the third triad.

The Song of the Parable begins with these words of strength: “There is a knowledge in me and a knowing and a perception. It is not sensed and not conceived. It is not recognized with the senses, not with the vision of the spirit. It is like a life.” And this knowledge came from Wolf’s ability to hear “a mighty roar over all being. In the roar everything that is. And above the roar a harmony. And the roar of the unison voice.”

Wolf continued on the theme of unity and harmony under She the creator: “Was nothing that was not in her, nothing that was not her. From her sound arose Allness. From the sound of Allness she arose. There was not she nor anything else.”

Then in his perhaps most mystical mode Wolf wrote: “Standing between immovable and immovable. Between the timeless and the timeless. Between the spaceless and the spaceless. Your body: From that which is not yet not being, to that which is no longer being, a bond.”

Here Wolf accepts the facts of life: “Within it lay the triad: BECOMING-EXISTING-PASSING AWAY. Its wave swallowed up everything created. All that remained was a vapor.”

Yet from all of its spiritual language, Confessio concludes with the primacy of mankind: “In its center a white glow. Banded its rays to the moving. To the unmoving. Penetrated being and the insubstantial. In the innermost brightness of the glow lay and shone THE WORD OF MAN.”

This is the second plate of the third triad.

This is the third plate of the third triad.

Commentaries and remembrances

Richard Benz

Johann Eckart von Borries wrote that cultural historian Richard Benz was a person Wolf met after World War I and with whom “he would remain in friendship and admiration for life.”

In an essay written in December 1949 (and sent to me by Leigh Firn), Benz began: “Among German graphic artists of the last half century Gustav Wolf is a tragic figure, not only because–though deeply rooted in his Badensian homeland–he had to emigrate abroad and there virtually died of homesickness, but also because such a great energy as his, which overflowed in an abundance of creative work, did not receive either here or abroad the appreciation which it deserves and so he was not able to exercise upon our art–which oscillates between extremes and is bound to prejudiced ‘isms’–the influence [that] normally should have come from his work, which is based on a truly visionary and cosmic ‘Weltanschaumg’ [world view] and on versatile craftsmanship….

“From a particularly fruitful start in the so-called ‘Art Nouveau’ style and from stimulations of the art of the Near East and the Far East, of the Islamic as well as of the Japanese, Wolf drew the courage to develop his own art: graphic and ornamental. It was not an end in itself of rhythmic play but bearer of the spiritual, which unfolded itself at first in cosmic fantasies, in world and star constellations, in primeval organic and un-organic elements and was almost connected with poetic and visionary or deep mystic words in hymn-like prose, a gift of his poetic vein.

“All shape or form or image became first a symbol for him. A symbol which was in close relationship with the symbols of words, types and letters. Thus he arrived to the black-and-white art of the woodcut, to the woodcut as it once was alive at the beginning of the 15th century in the Incunabulae, to the side-by-side of picture and type, uniting them in the ‘abstract’ line. The linear and the symbolic gave something of the character of a huge picture book to his graphic portfolios.

“His style was already established at the beginning of the century. His Confessio, a series of black-and-white plates with his own text which evoked a sensation at the time, originated in 1908 and shows the sovereign master of the wood-engraving technique. In Germany his recognition was limited to his close Badensian homeland. It must have filled him with joy when old Hans Thoma climbed up the four stairs to his studio to admire the large canvases with his cosmic fantasies in rich brilliant colors or when subsequently he hand-colored his other woodcut sequences.”

Mathias Hess

In his book on Gustav Wolf, von Borries reprinted a 1950 newspaper article by Mathias Hess:

“As his earliest student when he started [in 1920-21] his teaching career as a professor and head of the graphics department at the Baden State Art School in Karlsruhe, I got to know the graphic work he had created up to that point, his books and the work that dealt with color. The ‘Wolf Class,’ which gradually came together, worked on various tasks under his leadership. Since Wolf, as a well-known book and commercial graphic artist, was overwhelmed with commissions, a real workshop business developed. This gave us all the extraordinarily valuable opportunity to create for ‘life.’ Woodcut posters with drawings and typesetting, newspaper headings, certificates of honor written on parchment, Ex Libris [bookplates], and all sorts of other things as the day brought, were created there in the workshop on Westendstrasse ….

“Since I, as a small farmer’s son from Walldorf, had little access to Wolf’s world of ideas, as he built them up in the sentences of the Confessio, the work under this friend and teacher became particularly fruitful, where his example was in the craft (and in reference to every good example in the realm of creative art), clarified our understanding, and helped us. Every one of my classmates will confirm that the highly intellectual artist and writer Gustav Wolf was a person of kindness and manners; that our admiration for him and our attachment to him were of a kind that, how in a human life, perhaps under a lucky star, one day grows as a teacher and friend.”

Kurt Martin

Von Borries also include parts of a letter by Kurt Martin that appeared in the 1961 issue of Labyrinth 2:

“They remind me of the figure of Gustav Wolf with his almost always restrained and depressed features, which were only rarely freed with a short laugh. Despite all his seclusion, he still had a circle of friends connected to him; Richard Benz above all, and Alfred Mombert, René Schickele, and Annette Kolb. He was on good terms with the painters and sculptors of the Baden Secession, the spokesman of which I was at the time, but without any real obligation. Independence was crucial for his life and work, not as freedom and arbitrariness, but as order and freedom in which he wanted to live as unobtrusively as possible. That’s why, soon after he took over and without any external reason, he resigned from his teaching position at the Karlsruhe Academy; because he felt disturbed by this environment.

“Actually, Wolf is only known for his woodcuts, mostly large-format sheets that form cycles. For a long time, it remained incomprehensible to me how little his painted work corresponded to these woodcuts. Here, a direct graphic power with which he tried to capture visionary themes, processes of creation, cosmic events in which ‘the spirit floats above the waters.’ And then there are portraits that were executed as commissions, landscapes and still lifes; alongside the turmoil of the elements, a sensitive painting, true to reality, reserved like the whole personality. Wolf felt this contradiction and suffered from it without being able to transfer one into the other and unite it with it.

“It must have been the craftsmanship of wood cutting and setting rather than the vision that enabled Wolf to condense the symbol. For him, a sign was not just a means of communication that had become a form, a word from which a syntax could develop; the real sign was for him both a beginning and an objective….

“In 1930, an article by Gustav Wolf appeared in the ‘Baden Werkkunst’ [Art Works], which I was editing for the Baden Arts and Crafts Association at the time: ‘On the Nature of Signs,’ on which we worked together for long evenings. Here, is the sign as a means of artistic expression and spiritual content, as a ‘determination of a mental reality’ and as a ‘realization of inner truth.’ “

Max Fischer

Also included the von Borries book was a December 21, 1947 article by Max Fischer in the New York newspaper Staatszeitung und Herold:

“It is difficult to imagine that this lively, artistic person is no longer in this world. For as modest as he was, as shy as he became in situations where others used their elbows, he still had the fluidity of a strong personality, and his mannerisms, his voice, the dreamy shine in his eyes and his lively stories. The inflection of his Baden homeland, the skillful and graceful movements of his hands, have left a deep and unforgettable impression. The undiminished childlikeness of his nature and his great neatness of character made him truly lovable, and won him many friends.

“There was no graphic teacher more versatile than he, and the art school in Karlsruhe knew very well why they wanted to bring back this great artist and educator after the collapse of the Third Reich.”

Next UP

The subject of my next Gustav Wolf post will be his 1911 suite of two-color woodcuts simply named Zehn Holzschnitte (Ten Woodcuts).

Please send comments about this post to p1m1@comcast.net. Commenting directly through this website does not work.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/gustav-wolf-confessio/trackback/

Pingback: Gustav Wolf: His Monster Menagerie