George Walker: Wordless Novelist

Introduction

Graphic novels are alive and well thanks mostly for GenXers and Millenials. Their prototypes are Super Hero comics and the stoned-out world of R. Crumb. The Digital Age has certainly facilitated the generation of their images and reduced the cost of publication. But for me something is missing. When I think of graphic novels, I think of the work of Frans Masereel, Lynd Ward, Giacomo Patri and Laurence Hyde. Each of those 20th-century artists cut their images onto blocks of wood, and their wordless books are a series of relief prints. Has their craft expired?

Photograph by Michelle Walker →

Fortunately, I recently discovered, Canadian George Walker has picked up the torch of Masereel, Ward, Patri and Hyde. Furthermore he has served as an inspiration, a mentor and guide for a handful of other Canadian printmakers and graphic novelists. (Comments from three of them are at the end of this post.) For details of his background and development as an artist, I’ll refer you to his Wikipedia listing: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Walker_%28printmaker%29

As most discoveries happen these days, I came upon Walker’s art via surfing the web, namely by landing on the site for the Wood Engravers Network (http://www.woodengravers.net/) and then checking out the “Member Sites.” My eyes lit up when I arrived at George Walker’s website: http://www3.sympatico.ca/george.walker/ Once there, a little poking around let me to a video of his 2010 Book of Hours, a Wordless Novel Told in 99 Wood Engravings at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GtZ1ZIr6EP0 While I didn’t find the video’s music and environmental sounds all that entertaining, I was fascinated by the sequence of Walker’s wood engravings. The story he told was the 24 hours in the lives of those who worked at the World Trade Center before the planes struck. All of those mundane activities and dailyness are portrayed as blessings that would suddenly end in flames and the crush of collapsing skyscrapers. In short I thought it was the work of compassion and genius. I had to have a copy of his Book of Hours. I had to meet George Walker, at least electronically.

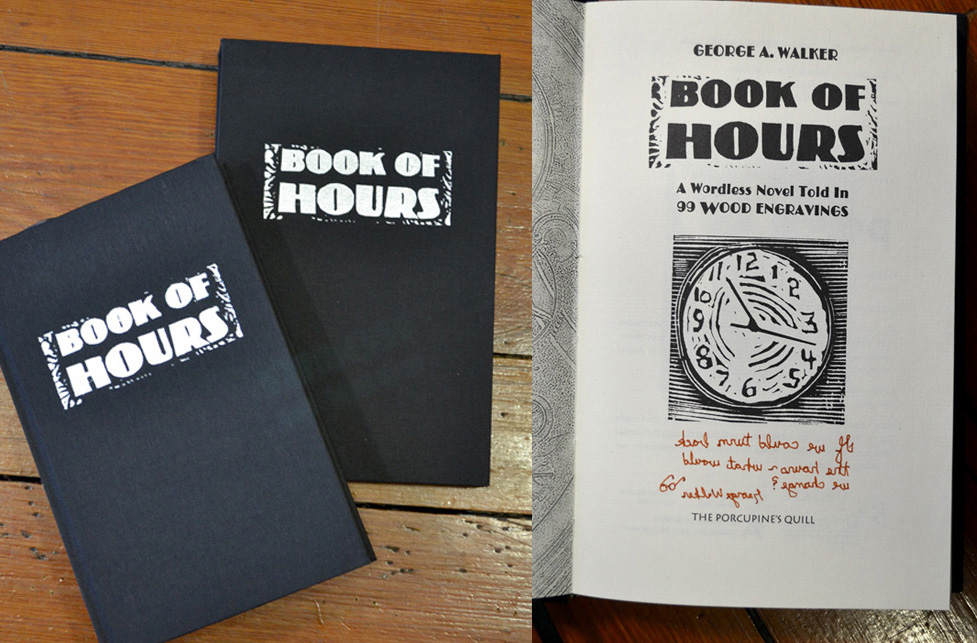

My copy of Book of Hours. Note George’s reversed inscription. (This and subsequent photographs are by Scott Ponemone)

Through our initial contact I was able to purchase Book of Hours from him. He had only printed 20 copies from the original blocks. They were long gone. But the trade edition had a smart cloth binding and slipcase. So I bought one from him that he signed. And as I do with all the artists I contact, I provided him with a link to my Art I See blog, which has proven to be a door-opener for conversations with artists. He immediately asked if I would review Book of Hours. I told him that I don’t do reviews but would gladly do a Q&A with him if he was willing. As you will soon see, he quickly agreed to do so.

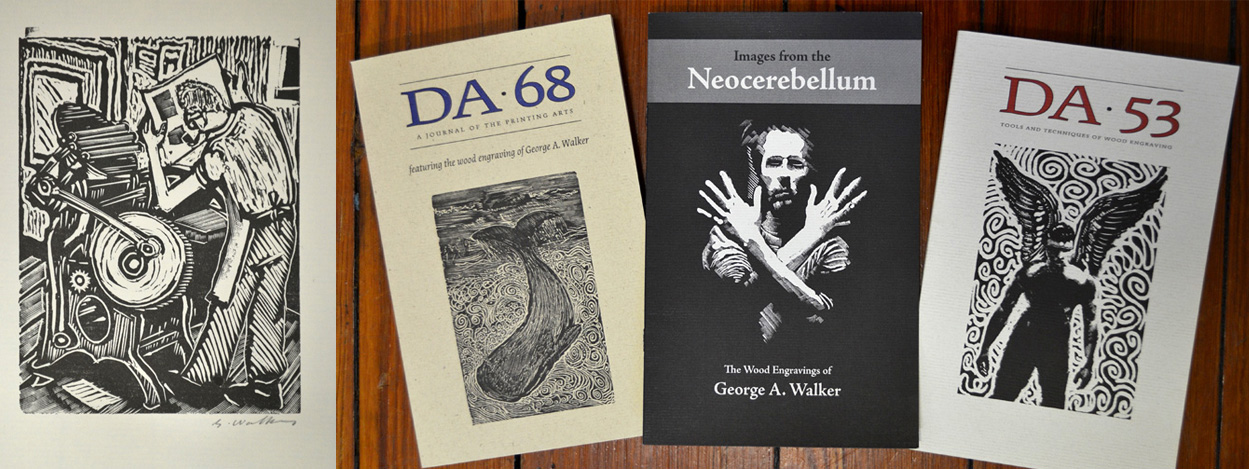

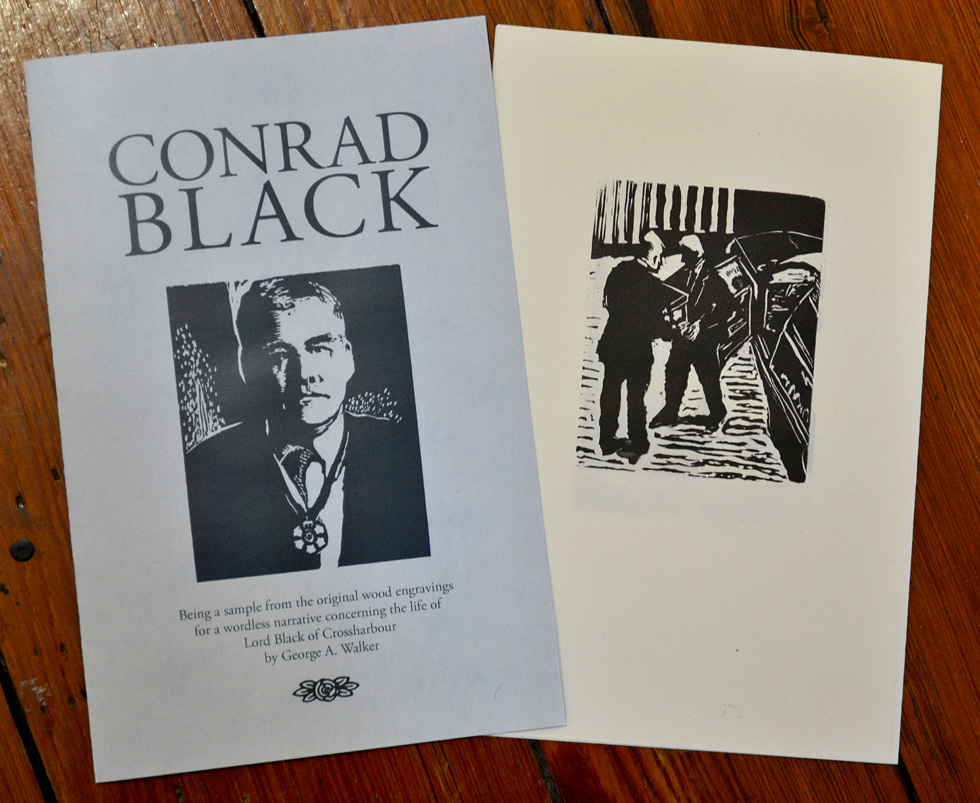

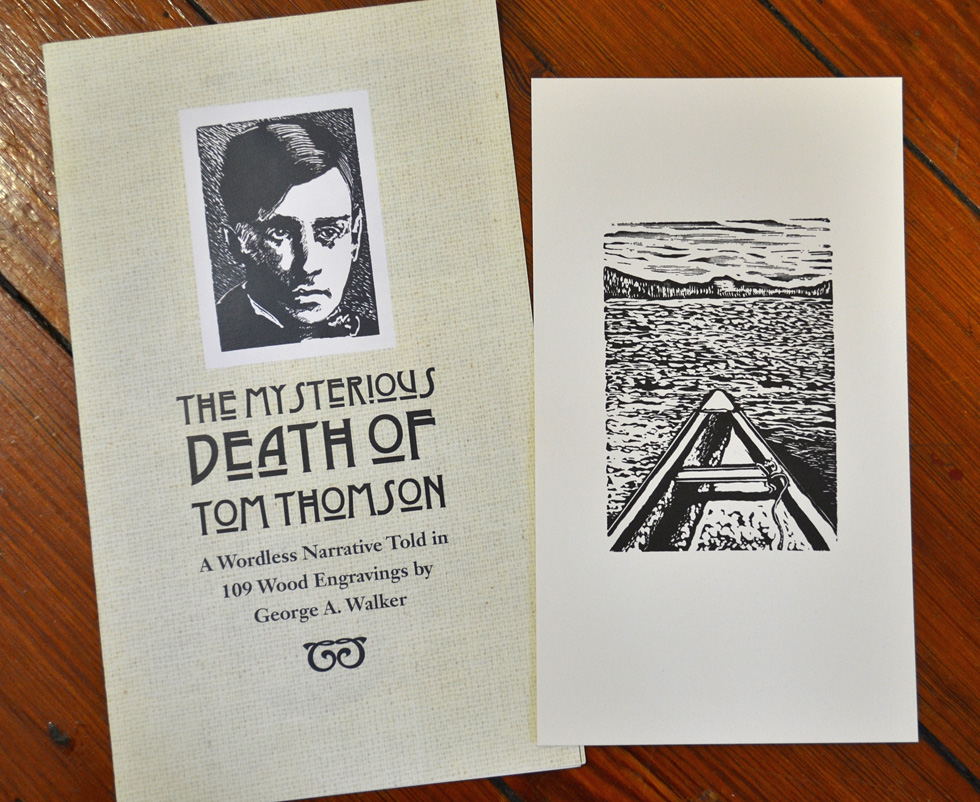

I should first note that when I opened the box with his Book of Hours, it was not alone. Beside a nice letter of thanks for the purchase, he included a sign copy of Written in Wood, a compendium of three of his wordless novels–The Mysterious Death of Tom Thomson, The Life and Times of Conrad Black, as well as Book of Hours; two DA journals of printing arts with articles on Walker (one with a signed Walker wood engraving); and prospectuses on three Walker books (Images from the Neocerebellum being the most intriguing) and flyers on two other of his books: Graphic Witness in which wordless novels by Masereel, Ward, Patri and Hyde reproduced, and The Woodcut Artist’s Handbook.

To keep the playing field even, I in turn sent him a signed wood engraving of my own.

Now on to the Q&A.

Interview

SP: Can you describe your attraction to wood engraving and how and where it began? Is it the process of cutting? Is it the end result?

GW: I trained as a letterpress printer, and when I attended college, a professor asked me to contribute images for a publication. He gave me some old wood type and asked if I could carve the images onto the back of these pieces of type. I found a book in the library about wood engraving and learned about the Sander Wood Engraving Company of Chicago who sold old commercial wood engraving blocks and tools. That sent me on my way. The love affair with the medium is partly because of the detail that can be achieved and high-contrast results. I love the contrasting effects of light that I can achieve in wood engraving.

SP: You seem early on to be quite inventive on tool use for cutting of the blocks. In what way is your approach to engraving on wood novel? Do you use tools not normally associated with wood engraving? Dremel use?

GW: Some people say that my use of power tools, such as a Dremel rotary cutter and mini router, are contemporary techniques that I have developed. I would argue that I merely used what I had available to me and that many other relief and woodcut artists have experimented with the media in the same way. The engraver Jim Westergard for instance has employed the use of a Foredom Rotary Tool for many years, and it was common practice in the last century for commercial wood engravers to use routers for removing large non-printing areas. Most artists find a way to adapt the tools and techniques of the process that align with their approach. It was once a requirement of the apprentice engraver to work with the local blacksmith to make all the tools required for the job. In this way apprentices gained a respect and understanding of the composition of the tools that they would be using throughout their career. It is out of that understanding that I have approached the use and modification of the tools that I use.

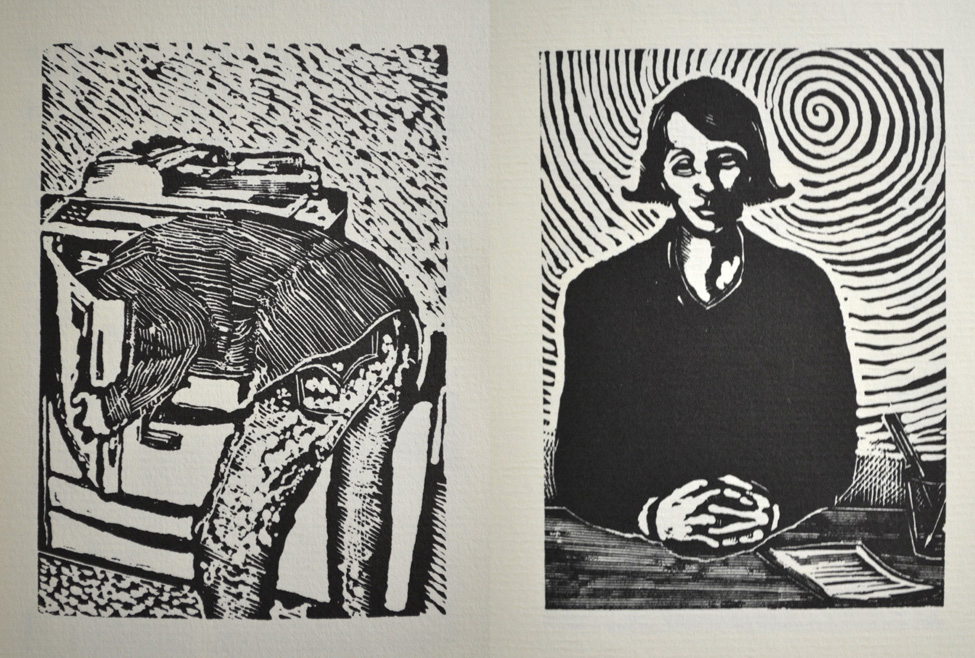

SP: In Endgrain (Barbarian Press, Mission, British Columbia, Canada, 1994) is your 1987 print Interior Still Life (below, left). Can you describe your approach to bock cutting then and what tools you used?

GW: I was still using a typewriter in 1987! If I remember the image correctly it is of a desk with a manual typewriter and an empty chair. I also titled this engraving, “If I only had time to write.” I suppose my approach hasn’t changed that much. I still make my own blocks and primarily use endgrain maple. However, I am experimenting with using some custom blocks made by Scott Moore. I used the Dremel with a round bit head so that I could achieve a free white line effect on the floor and the desk. It also helped make the keyboard on the typewriter easier to render. I contrasted this technique with hand work using the lining tool to create tonal contrast.

(left) Interior Still Life, wood engraving (1987); (right) wood engraving from Book of Hours (2009) (These two images were provided by the artist.)

SP: How has your approach to cutting blocks changed since then? Can you offer up a recent image and describe how it represents either a change in your approach to conceiving a wood engraving or a change in your cutting of the block?

GW: Above is an engraving from my series Book of Hours (2009) that shows a startled girl at a computer monitor. Although I am still a spontaneous engraver who likes to work quickly —I am increasingly more interested in how the image appears out of the blackness. In contrast to the earlier work I use hand tools more often than the Dremel. I try to cut less and get more image for my scratch marks

SP: The essays I’ve read state that your early wood engraving served was illustrations to text. How did the portfolios Beau Monde and Images from the Neocerebellum come about? What did you learn about yourself as a printmaker doing each?

GW: Beau Monde explores the marionette as a symbol for modern life and its perplexity of meaning. I was trying to communicate an inability to live freely because of the will of the master puppeteer who represents society. Pull one string the hand moves, pull another my leg and yet another and I am tangled. If they are all pulled at once, I’m torn into pieces. Bergman said it best in his Life of the Marionettes, “One of ennui’s most terrible components is the overwhelming feeling of ennui that comes over you whenever you try to explain it.” My wife wrote a poem at the beginning of the book that tries to capture all these feelings.

Images from the Neocerebellum is my dream diary. In this collection I am trying to exploit the REM state by documenting my lucid dream fragments from my personal visual dream diary. I started a visual dream diary while still in college on the advice of Dr. John MacGregor. Influenced by Carl Jung’s theories of the dream’s relation to the unconscious, I began to explore the dioramas encountered in dreams, distilling them into single black-and-white images in an effort to capture unconscious moments in time. (The neocerebellum is that part of the brain that controls visual spacial, procedural learning and the preparation of complex movements such as would be required in the engraving of lines on a wood block.) In the tradition of printmakers such as William Blake and the French Symbolist Odilon Redon, I was trying to reveal the psychoanalytic process of bringing the unconscious into the conscious.

SP: Can you recall the initial impact (and when was it) on you of the graphic novels of Masereel, Ward, Hyde and Patri? Why did they have such an impact that you would conceive of doing your own? Why did you think your work would lend itself to a graphic novel?

GW: My fascination with Masereel and the wordless novel began in the 1980s, after attending an exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario featuring the work of Frans Masereel. I bought the catalogue for the exhibition (which I still have). Masereel is regarded as the first master of the wordless novel. He went on to influence Ward, Otto Nückel, Patri and Hyde. After seeing the exhibition I began an obsessive pursuit to find books illustrated with woodcuts, wood engravings and linocuts, and to learn everything I could about fine art printmaking and the art of wood engraving.

Living in a rough part of the city of Toronto and being desperately poor myself–trying to balance college expenses with low-paying part-time work–I often felt like a character in a Masereel novel. The building that I lived in housed a stew of characters, ranging from prostitutes to con men. I once had to disarm a kid, not much older than 10, who pulled a knife on me and demanded my bike. At the time words didn’t communicate my feelings. Pictures seemed more poignant and accessible to illustrate this world. It was exhilarating to plaster my woodcuts in the neighborhood, criticizing the landlord and poking fun at the politics and injustices of the day, and today I can identify with Masereel’s words: “Since the time of my youth, I have protested against the society in which I am living. The social injustice seemed odious to me, and I believe that this early rebellion became the source of many of my works.”

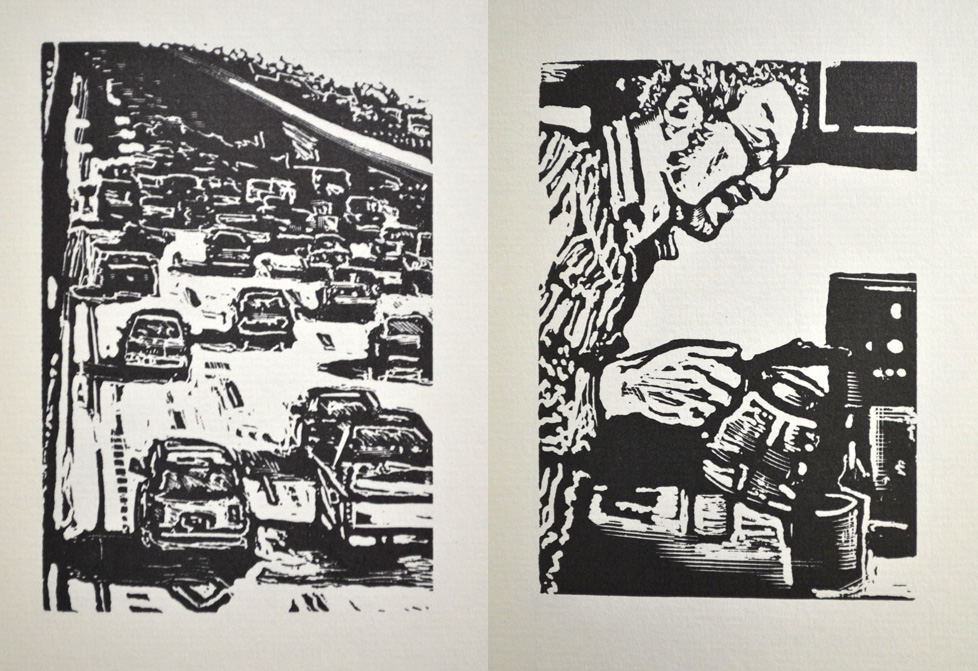

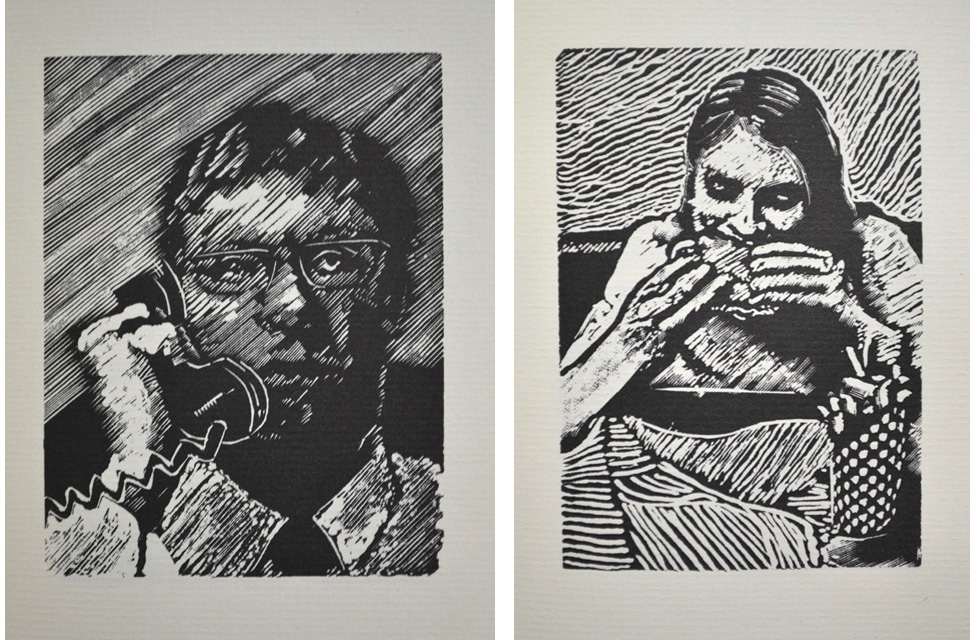

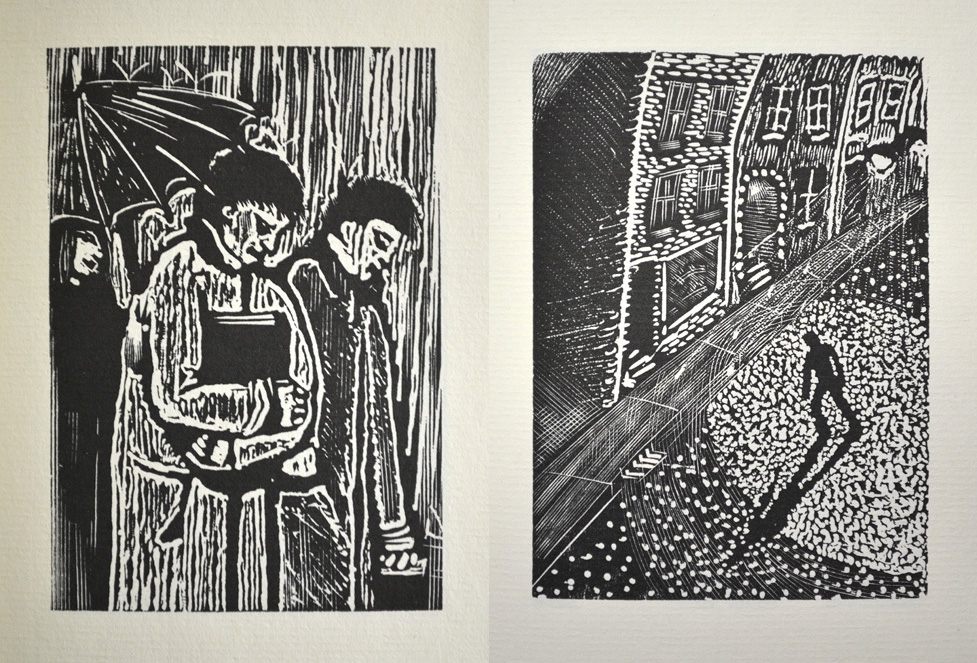

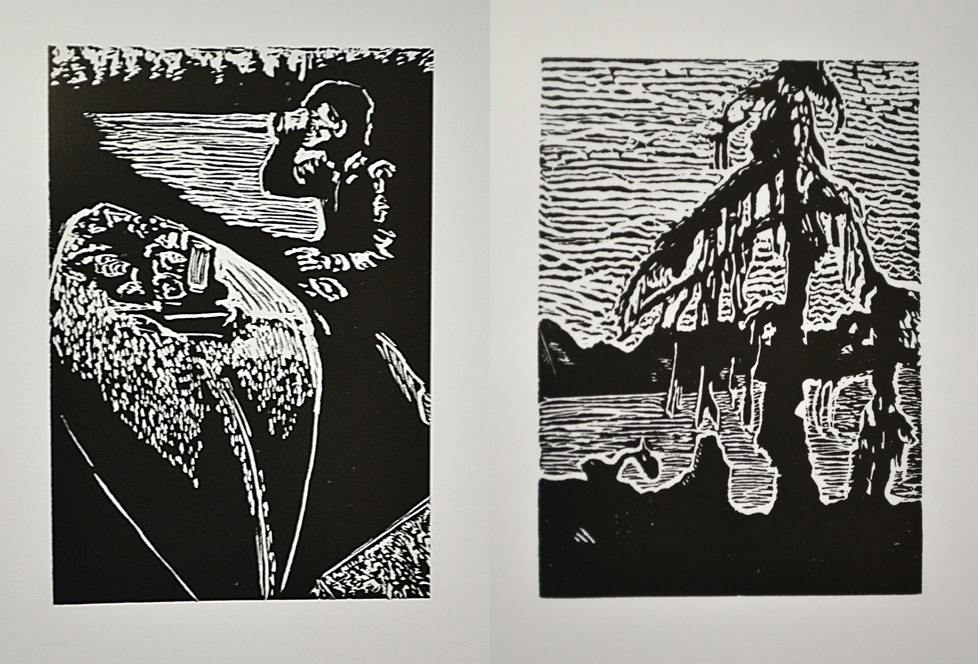

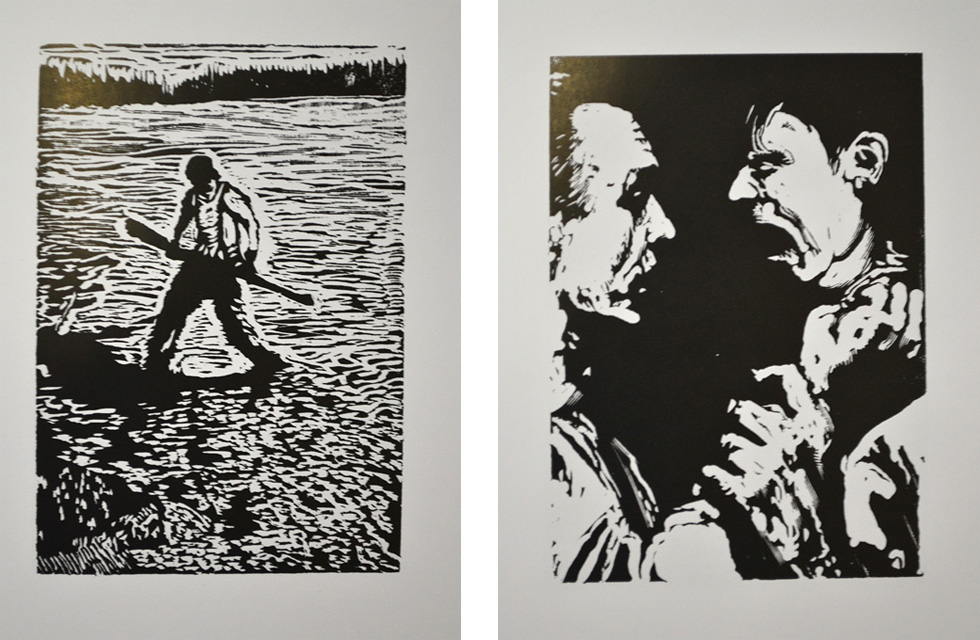

The following illustrations are from Book of Hours. The pairings are totally my own, selected to show both the nature of Walker’s story-telling as well as the variety of marks he uses to create his images. The sequence shown here does not correspond to the book. Moreover, in the book the images only appear on the recto side of each leaf.

SP: Why did you do your Book of Hours? How did your approach to this graphic novel differ from Masereel, Ward, Patri and Hyde–in the conception, sequencing and/or cutting?

GW: I have had a long fascination with the picture narrative that stems from my childhood obsession with comic books and later the discovery of the wood engraved wordless narratives of Frans Masereel, Lynd Ward and Laurence Hyde. The Book of Hours came about because I was interested in how certain events in culture change the direction a society is headed. Just as the sinking of the Titanic showed how technology is not invincible; the events of 9/11 changed our idea of how power operates in tandem with economic policies, notions of security and our faith in the concept of nationhood. Like Masereel, Ward, Patri and Hyde I am interested in social justice and the issues that effect it in society today. My narratives are constructed through researching the documents and images around my topic. I move images around just like the writer might move words and paragraphs. I diverge from Masereel, Ward, Patri in that many of my narratives have characters and places that can be identified with real people and places.

Why did I create the Book of Hours? The events of 9/11 are difficult to rationalize and understand. The horror around 9/11 represent the worst of our world . We can write volumes about the circumstances that led to this disaster and still we are perplexed by such hate that seems counter to the religious beliefs that some claim inspired it. For me the only way to explore the complexities of 9/11 is in a wordless narrative. The story becomes about symbol and sign and allows for multiple narratives to exist at once.

The picture narrative becomes the symbolic code for the reader to decipher when the traditional text is missing. This type of reading pictures is similar to the idea that Roland Barthes expressed in his essay The Third Meaning. Barthes describes a level of signifier that is beyond his categories of communication and symbol and reaches deeper into a “poetic” realm of meaning. My wood-engraved narrative does not provide the reader with the whole story. Rather, it sketches the story through a visual sequence that relates closely to what one might experience in a dream.

Today we follow a book of hours that is not written down. The cultural habits and norms of a society can be imbedded in the consumption of popular culture. Most North Americans follow a 9-to-5 job with an hour for lunch. Millions watch television religiously and follow all the popular media in the pursuit of entertainment, truth and meaning. Like the Book of Hours in the Middle Ages, the popular media provides a path to salvation known as the American Dream. It is open to interpretation whether the American Dream is the path or the salvation or both or neither.

SP: Each of those authors’ images were quite uniform in appearance (cutting style, tool usage) image to image. But you seem to take a different approach. With each turn of the page I’m surprised (delighted) by how the next image was cut. How do you decide how to approach the cutting of each image?

GW: I sometimes engrave as many as 10 blocks in a week. Some of them are good, and some of them are terrible. I am trying to capture a mood, feeling, moment or scene, and I work quickly to transfer these emotions into the wood. This is why some of the marks in the wood do not look carefully planned or executed — I am trying to convey expressionism and emote a transfer of information to the block. I will, however, make marks that take time and concentration. The image dictates the approach. Some images demand more attention, more time, more scratching beneath the surface to reveal what it is I’m after. It’s about focus: Some images are focused and others are scratched through darkness.

SP: Some of the images appear to have been adapted from photographs. Is that so? Why did you use photos as source material?

GW: I distort the images I quote from photographic references. They are wood engravings yet they reference the ability of the photograph to capture the “snapshot” in time.

Susan Sontag discusses the importance of the photograph in our time in her book On Photography. She relates a photograph’s ability to capture “reality” and how the photographic image documents a state of truth. But by the end of the 19th century it became apparent that the camera could lie, and at that point, Sontag argues, photography became even more popular. I am interested in the trust that we have in the photograph, and I like the irony of the photograph simulated on the surface of a piece of wood. Because some of my work involves documentation (like the Book of Hours, The Mysterious Death of Tom Thomson, Conrad Black and Leonard Cohen), I am interested in that space between what is documented and what is “reality’.” I use photographs as reference and as a form of quotation from pop-culture. The fun lies in the middle because they may look like a photographic reference, but (in many instances) they are not. The image becomes a parody of the medium that they pretend to represent.

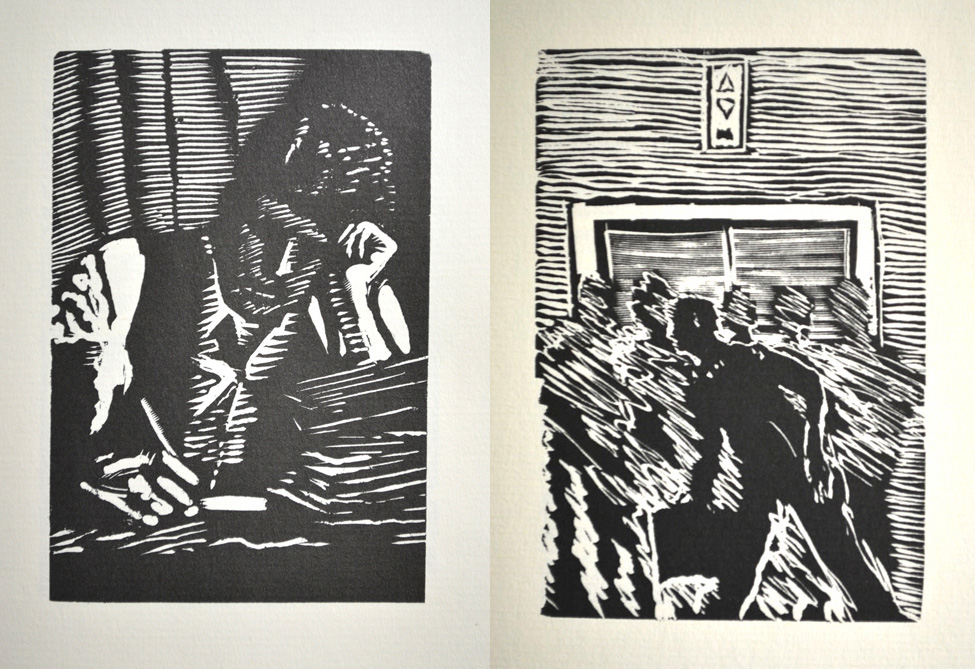

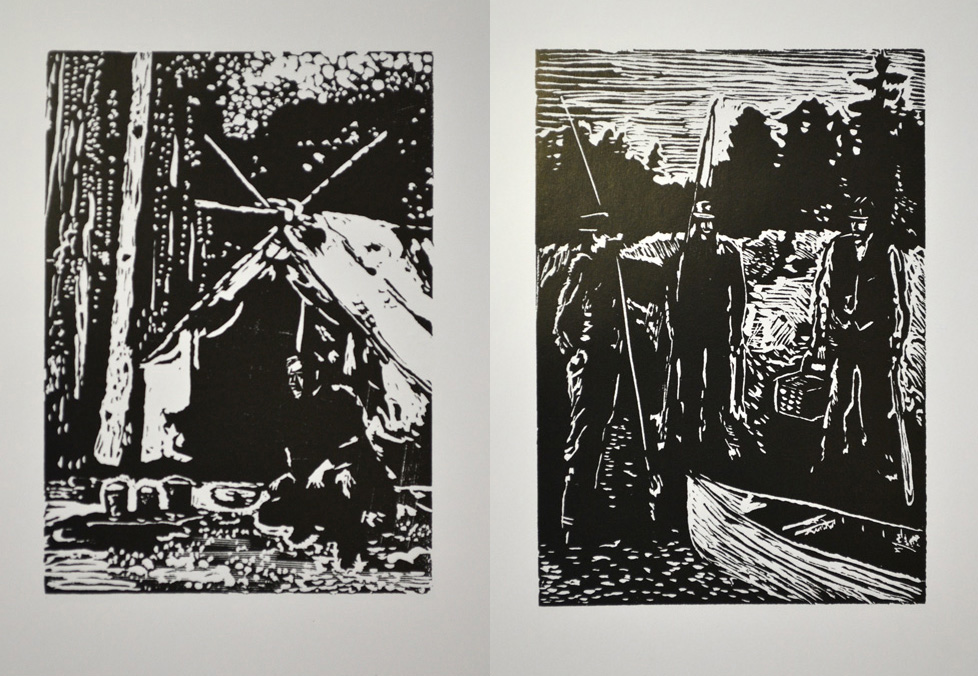

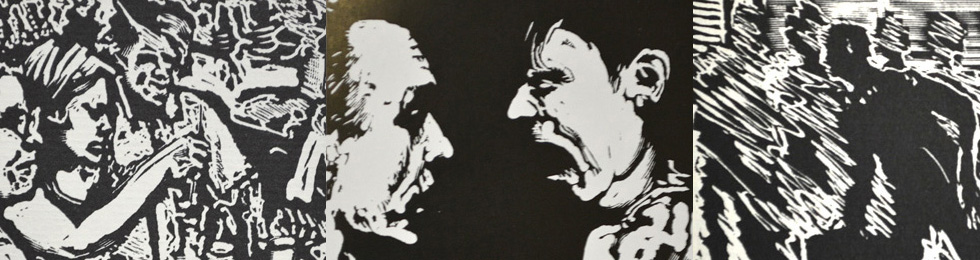

The following images are from Walker’s The Mysterious Death of Tom Thomson. Once again this presentation is my own–not the book’s– juxtaposition of images.

SP: Some of your predecessors stuck to one block size throughout their graphic novel? Masereel was pretty consistent; Ward wasn’t. The blocks in your novels are. Why?

GW: It’s partly for the efficiency on the press. It’s easier to proof blocks quickly if they are all type high and the same size. The other reason is that I buy the wood by the board length, which makes all the blocks the same dimensions. If I have a block that is damaged or I have a piece of odd size wood that I am inspired to use, I will use it. I am also concerned with the image as text in my narratives. I believe the consistency of the image size helps support the idea of the image as a textual frame.

SP: Why do you use numbers that you feel are significant to determine how many blocks per book and the size of editions?

GW: This may seem strange but…. In Viktor Frankl’s book Man’s Search for Meaning (1946) he describes his psychotherapeutic method of self discovery, which involved identifying a purpose in life to feel positively about and then imagining that outcome. How then you may ask does this relate to my obsession with numbers? Lewis Carroll is the short answer. As well as being the author of Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland, Carroll was a math teacher in Oxford, and mathematicians argue the Alice books are full of algebraic lessons and references. I love the notion of hiding mathematical meanings in my images and in the construction of the narrative. It makes for a quick answer for why 80 wood engravings and gives me a goal for when the visual narrative must conclude.

My friend David Day is publishing a new book on the math coded into the Alice books. Watch for it here: http://www.lewiscarroll.org/tag/david-day/

SP: How is your work a spiritual journey?

GW: I am still learning what my spiritual journey is. Epicurus believed in a basic connection between learning and happiness. The entire purpose of learning was to attune the mind and sense to the pleasures of life. I am not seeking a spiritual thing; I am searching for a spiritual experience and meaning. I am investing through my art, a pursuit of meaning, to remove me from the distractions of meaninglessness. Although few of us acknowledge its existence as such, meaninglessness inhabits much of contemporary culture in the form of things that teach us nothing about ourselves or do not contribute to our growth. The scratching and engraving of wood blocks gives me a path to move beyond this.

SP: What’s next?

GW: I am currently working on the life and times of Pierre Elliott Trudeau (former Prime Minister of Canada) in 80 wood engravings. Trudeau, was the 15th Prime Minister of Canada from April 20, 1968 to June 4, 1979, and again from March 3, 1980 to June 30, 1984. I am interested in how he appeared in culture, pop-media and his influence on a generation of Canadians. Here’s a proof from it. (Image courtesy of the artist.)

SP: What is your feeling about the graphic novels that are being produced using non-traditional technology? Are there any that you are particularly fond of? If so, which ones?

GW: I admire this cultural renaissance of the comic book in its new form of the graphic novel. The acclaimed comic book artist and creator of Maus, Art Spiegelman, hates the term “graphic novel.” He told me recently at the Art Gallery of Ontario that the problem with most contemporary art today is that it lacks narrative. Where’s the story? This is why I pursue the image as a form of text and story telling.

Comics are counter culture! They have a subversive history and were burned in the U.S .after the Senate subcommittee hearings on juvenile delinquency and crime in the 1950s. They were considered dangerous after the report in Dr Fredric Wertham book Seduction of the Innocent. He proposed that comic books were directly linked to juvenile crime. How can you not want to be associated with banned books?

I like the work of Marjane Satrapi, Kate Beaton, Joe Sacco, Seth, Chester Brown just to name a few comic book artists who I admire. In this late age of print I suppose non-traditional technologies means anything but print. My hunch is that print isn’t going to disappear. Its value lies in the fact of its physical quality. Everything else is a simulation of the object of print. We are by nature prone to possess the object, and unfortunately for the ethers of the digital world we are only duped into thinking we are experiencing paper!

SP: How is your work being received by these young graphic novelists? Do you show your work at fairs where most vendors are of a younger generation?

GW: I really can’t speak to how the younger generation likes or dislikes my work. There are a lot of talented young people out there and I am certainly flattered if they find some meaning in my work. As an Associate Professor at OCAD University [formerly the Ontario College of Art and Design] I engage with many young minds and I really enjoy the dialogue and debate about images and text and the role of the zine, graphic novel and comic book in culture.

I do a few shows a year in which I show my books and talk to people who are interested in the genre. The Toronto Comic Arts Festival (TCAF) is a favourite show of mine. You can find out about it here: http://torontocomics.com/about-tcaf/

I am always interested in the ideas and projects of the young. My granddaughter and I enjoy making hand drawn comics together. I have learned so much about Pokémon and Furbies from her!

SP: Do you have any proteges?

GW: There are a number of people who I have mentored through the process. Some students have gone on to get published, others have not. I think they were all talented and thoughtful people who I enjoyed listening and learning from. I just hope that they felt I contributed in some way in their growth as artists and people.

I then pressed Walker for some names. His response:

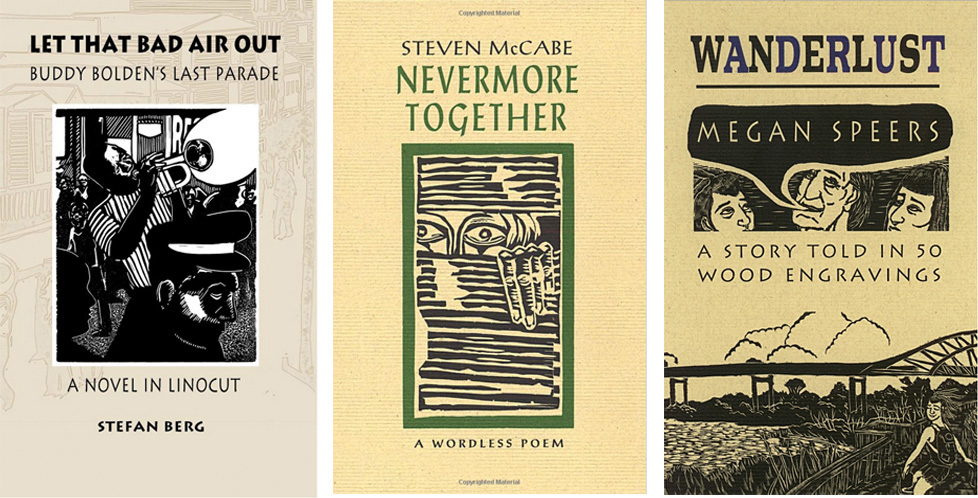

Yes I helped Marta Chudolinska, Megan Speers, Stefan Berg and Steven McCabe get their books published by the Porcupine’s Quill, Walker’s publisher (http://porcupinesquill.ca/). Marta and Megan were students of mine, and Stefan did an independent study with me. But Steven McCabe is older than I am, and I merely recommended him to the Porcupine’s Quill as a friend. I cannot speak to whether they see me as a mentor or not. You would have to ask their opinion directly.

Testamonials

STEFAN BERG

SP: How have George’s relief prints and his books without text influenced your own work?

SB: George introduced me to the wordless novel form. His engravings were for most an entry into the possibilities of this form. Aesthetically I found in them an approach to image making which was very different from my years of painting, to work in black and white, to see things graphically, a structuring of form closer to charcoal drawing. His work is remarkably fluid for engraving, a technique typically fraught with organization and cleanliness, working in a medium which does not allow for mistake or correction, he retains an element of the searching process akin to Masereel. I think his approach to narrative is a particularly inventive and contains something other graphic artists lack. It’s incredibly vibrant. Light and composition are the absolute key elements in relief printmaking, and George has understood this, and he teaches this, without a single word. The truth is George doesn’t really talk about how to cut a block. He shows you how through example, this is more valuable, more tangible.

SP: In what ways has he helped you creatively?

SB: His presence is enough to get you thinking and feel excited about art, new or old. He is someone who inspres very naturally, genuinely, I believe his enthusiasm and rigor helps to inspire many many artists at an early stage in their development when it is most crucial. As Baskin said of Eakins, “He is a force.”

SP: And in what ways has he helped you get published?

George essentially got me published, out right, full stop. He gave me an offer all students need, a reason to work really hard and push for something one would never do without the expectation or reward. Carving 70 lino blocks is no walk in the park, but when there’s a clear shot of publication, you get it done.

STEVE McCABE

I consider George Walker both a colleague and a mentor. He is a colleague in the world of creative artistry and a mentor in the field of relief prints and wordless books (and, by extension, what they lead into). My experience in developing Never More Together for The Porcupine’s Quill, with George editing the wordless book series, was rewarding and educational. Our planning conversations showed me his imaginative depth in connecting sequential imagery to related fields such as history, media, or philosophy. Working with George was like a 3D exploration into possibilities of both story and linocut. At key moments, as the book of images progressed, George was specific with suggestions, like a poetry editor, and these directions both opened and aimed the narrative. George is also quite masterful concerning the relief printmaking process and shares his knowledge generously. I experienced George’s mentoring as enriching, full of surprise, and practical in developing technical skills.

MEGAN SPEERS

I would definitely consider George a mentor. Beyond helping me get published, he encouraged me to create a wordless book in the first place.

The fact that he was one of the few professors who focused on relief printing specifically meant that I was drawn to his work. When he introduced the concept of the wordless book, initially starting with The City by Frans Masereel, I fell in love with the medium completely, especially when George talked about its political history. He always discussed the connections between politics and art in his classes, which was a very positive thing for me because my interest has always lain in politicized art. Learning the history of this slightly obscure medium was extremely inspiring to me when I was a student.

Creatively, he was always very encouraging, his attitude was always an enthusiastic one and he always encouraged all of us to push our ideas and mediums further. As far as assistance with publishing went, I doubt I could have gotten my book published without his connection to the folks at Porcupine’s Quill. He also laid out for me step by step how to properly scan and prepare all of the prints from my book for publishing, which was very helpful as my knowledge of computer editing was fairly minimal at that time.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/george-walker-wordless-novelist/trackback/

Pingback: Walker & Berg: Updates on Wordless Novelists |