Snarking at the Cottage with George Walker

INTRODUCTION

This is a “Blame it on the Pup” or “Careful When you Make a Gift” tale. First I’ll blame it on Prado, our 13-year-old airedale. My husband Michael and I didn’t want to board him during our next vacation. So I reached out to our good friends in Toronto, George and Michelle Walker, whom we haven’t seen in a few years.

(Readers of my ART I SEE blog perhaps are familiar with the name George Walker. Due to his wonderful production of wordless books of wood engravings, he has been featured in three posts: the initial post on his wordless novels, a combine post on Walker and Stefan Berg, on Walker’s 2016 Neocerebellum book.)

When Michelle suggested joining them at a lakeside cottage belonging to a friend of theirs, we didn’t hesitate. So we packed our car with Prado’s food and his vaccination certificate (which the Canadian border person didn’t want to look at) and spent two nights in Toronto so we could meet Stefan Berg, a young artist who is working on his second wordless narrative–a linocut biography of pianist Glenn Gould. (His book on New Orleans legendary horn player Buddy Bolden was featured in an ART I SEE post from 2015.) Then we drove two hours north of Toronto to Go Home Lake, on the southern edge of the Precambrian Canadian Shield.

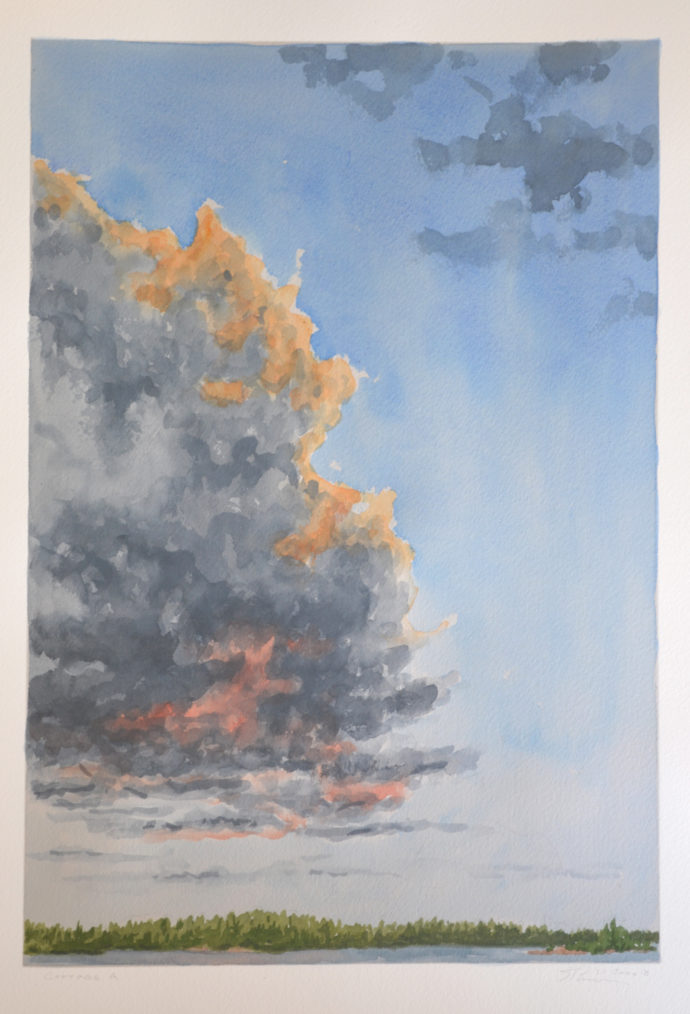

Sunset at the cottage. (Photo: Scott Ponemone)

Two things were immediately apparent: one, Prado loved being off-lead for eight days, wading in the water, rolling in grass and sleeping on the deck; and two, the sun set directly across the lake turning the confer forest-covered opposite shore into a ragged silhouette. This inspired me to do six watercolors of skies with the opposite-shore tree line anchoring each painting. George, meanwhile, cut 12 small wood engravings to illustrate a new edition of Lewis Carroll’s nonsense poem, “The Hunting of the Snark.” As a favor for the owner of the cottage, George, working with Dan and eventually everyone, built a balustrade around the screen porch.

Finishing up the balustrade, George places a picket at the corner of the porch as Prado and I look on. (Notice the sweater, hoodie and long pants on a late June day.) (Photo: Michelle Walker)

As a thank you for inviting us to join them, I offered the Walkers a choice of one of my watercolors. They chose the first one, which was of a morning sky.

Scott Ponemone, “Cottage A,” watercolor, 16” x 11”, 22 June 2018

Well, that should have been that. But not with George. Two weeks after we returned home we received….

(Photo: Scott Ponemone)

…containing 12 working proofs with pencil annotations for his Snark project. That, I emailed George, was a potlatch-type gift. In a potlatch feast, as practiced by First Nations peoples of the Pacific Coast of northwest United States and British Columbia, Canada, gifts are exchanged and the antes keep getting raised to ruinous levels as a way of boasting about wealth. George proposed that my next gift should be a blog post about his Snark project. So here goes.

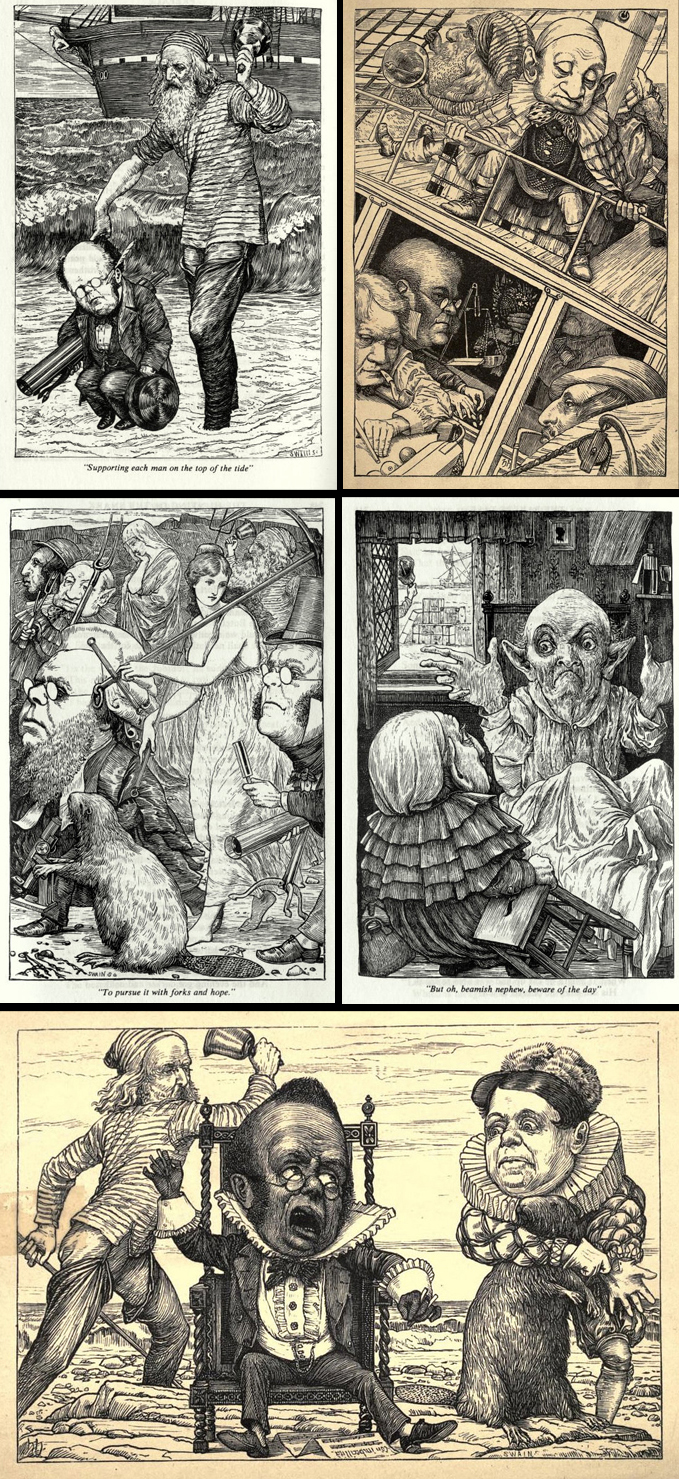

Carroll’s Snark

Lewis Carroll (the pen name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, 1832-1898) wrote The Hunting of the Snark ( An Agony in Eight Fits) between 1874 and 1876. It is often described as a nonsense poem. According to the Wikipedia listing, Carroll borrowed eight made-up words from his earlier poem Jabberwocky and never defined the word “snark.” The listing gives the following synopsis: “The plot follows a crew of ten trying to hunt the Snark, an animal which may turn out to be a highly dangerous Boojum. The only one of the crew to find the Snark quickly vanishes, leading the narrator to explain that it was a Boojum after all.” Henry Holiday illustrated the 1876 first edition with designs for wood engravings. According to an essay in The Public Domain Review website, “He drew nine illustrations for the book; a tenth illustration depicting a Snark was rejected by Carroll–he wanted the creature to remain unimaginable.” Macmillan in Britain printed a first edition of 10,000 copies. It became an instant success. Wikipedia says, “There were two reprintings by the conclusion of the year; in total, the poem was reprinted 17 times between 1876 and 1908.”

The covers of the first edition of Snark featured images by Henry Holiday. (Photo: literature.wikia.com)

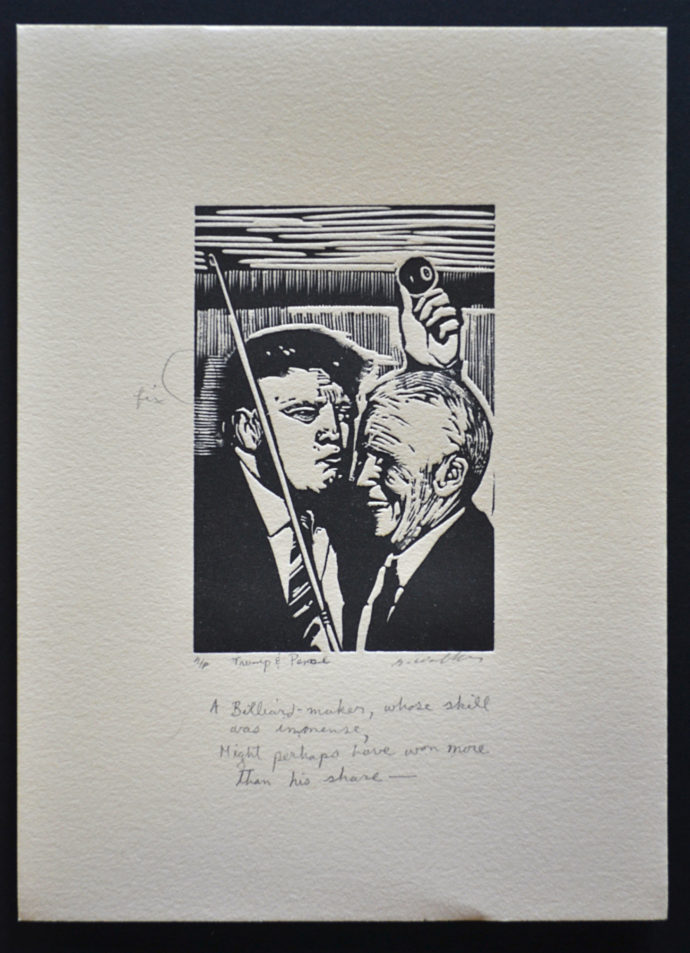

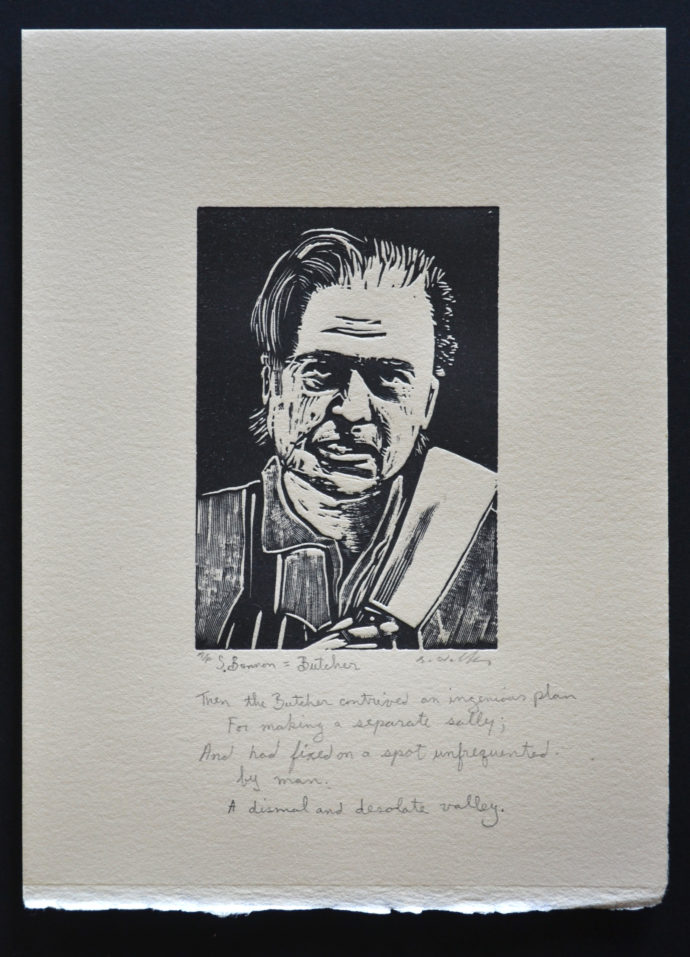

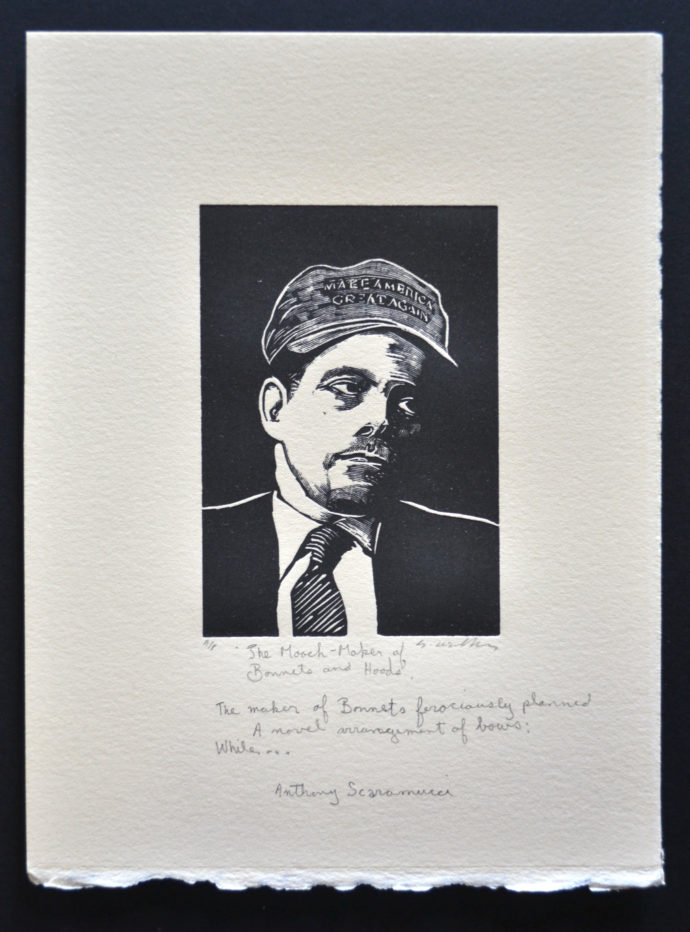

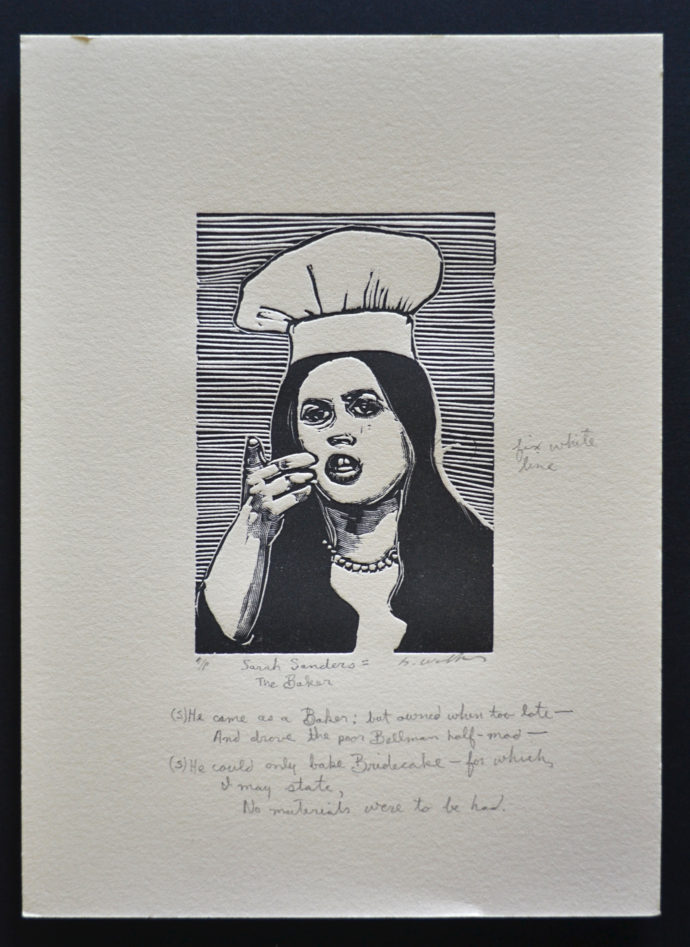

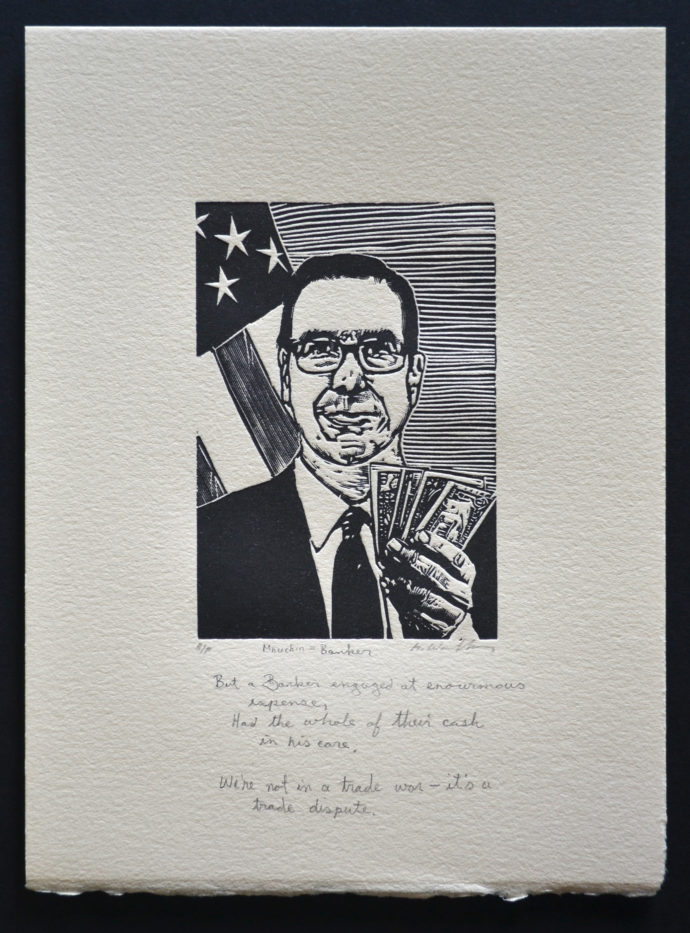

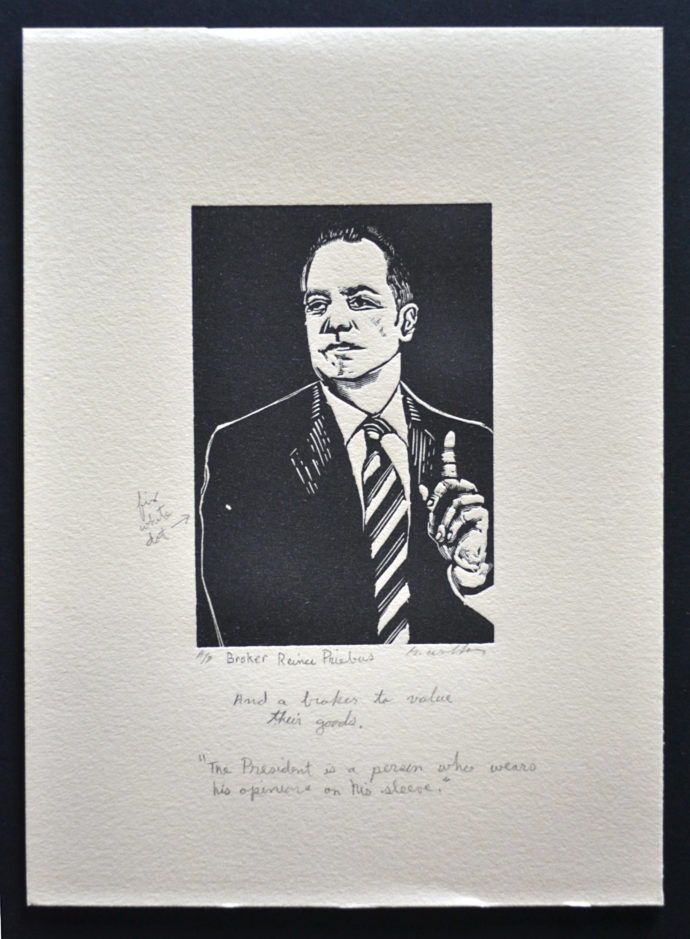

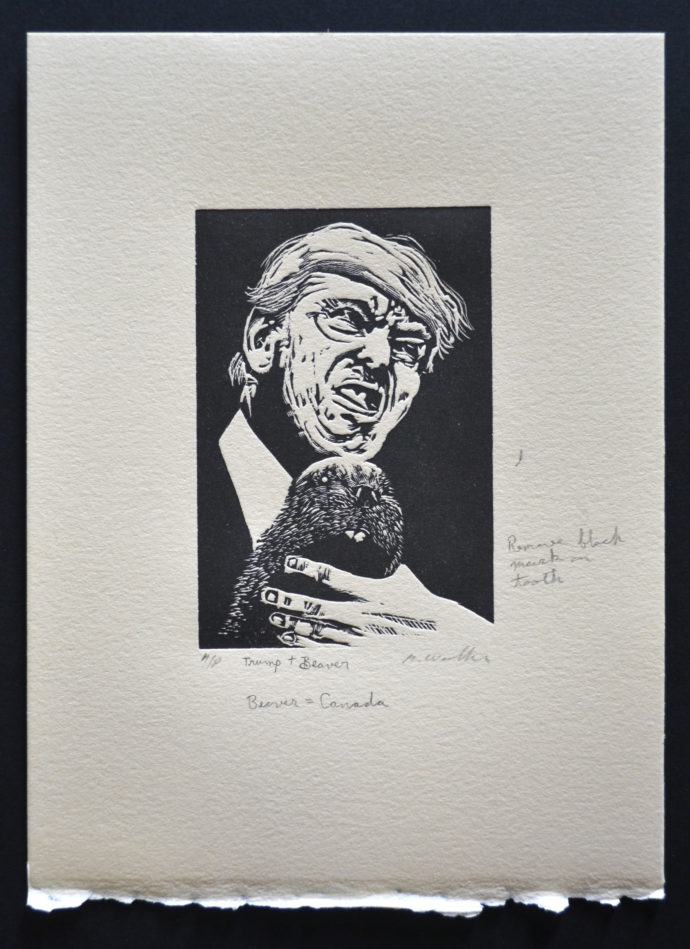

Wikipedia listing says: “Carroll often denied knowing the meaning behind the poem; however, in an 1896 reply to one letter, he agreed with one interpretation of the poem as an allegory for the search for happiness.” The hunting party for the Snark sets out on a boat. “The crew consists of ten members, whose descriptions all begin with the letter B: a Bellman, the leader; a Boots, who is the only member of the crew without an illustration; a maker of Bonnets and Hoods; a Barrister, who settles arguments among the crew; a Broker, who can appraise the goods of the crew; a Billiard-marker, who is greatly skilled; a Banker, who possesses all of the crew’s money; a Butcher, who can only kill beavers; a Beaver, who makes lace and has saved the crew from disaster several times; and a Baker, who can only bake wedding cake, forgets his belongings and his name, but possesses courage.”

A summary of the “Eight Fits” can be found the Literature Wiki website, while the full text of the poem is provided at a University of Adelaide web page.

Five of the Henry Holiday designs for wood engravings to illustrate the first edition of “The Hunting of the Snark.”

Public Domain Review’s Snark web page states: “The poem was incorporated into Carroll’s compendium of humorous poetry entitled Rhyme? and Reason? (1883). Since then it has been illustrated by a variety of artists and translated into many languages, and the book rarely goes out of print. People are known to memorise and recite the poem. Some people form Snark Clubs. There is a timeless nature about the verses that make it as relevant today as it did in 1876.”

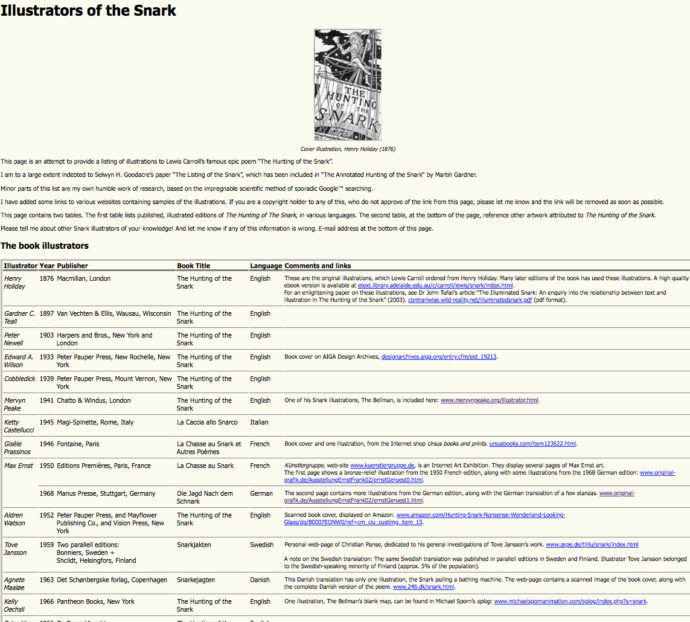

Snark has not only been wildly popular with readers. Dozens of artists have rendered their own suite of Snark illustrations. Thank goodness there’s even a webpage (the top of which is shown above) that tries to list all Snark illustrators. Starting with Holiday, this page names 46 other illustrators to editions of Snark including Max Ernst, Ralph Steadman and Barry Moser. Its most recent listing is 2008: Adolf Born, a Czech artist. The page also names eight artists who made Snark images that were not made for a Snark book. Finally, it credits Mahendra Singh for hosting “an amusing, ever evolving blog of Snark illustrations”: http://justtheplaceforasnark.blogspot.com/ As of this writing, Singh’s most recent post was 30 July, 2018.

George Walker cuts into a maple wood engraving block at the cottage. (Photo: Michelle Walker)

George’s Snark

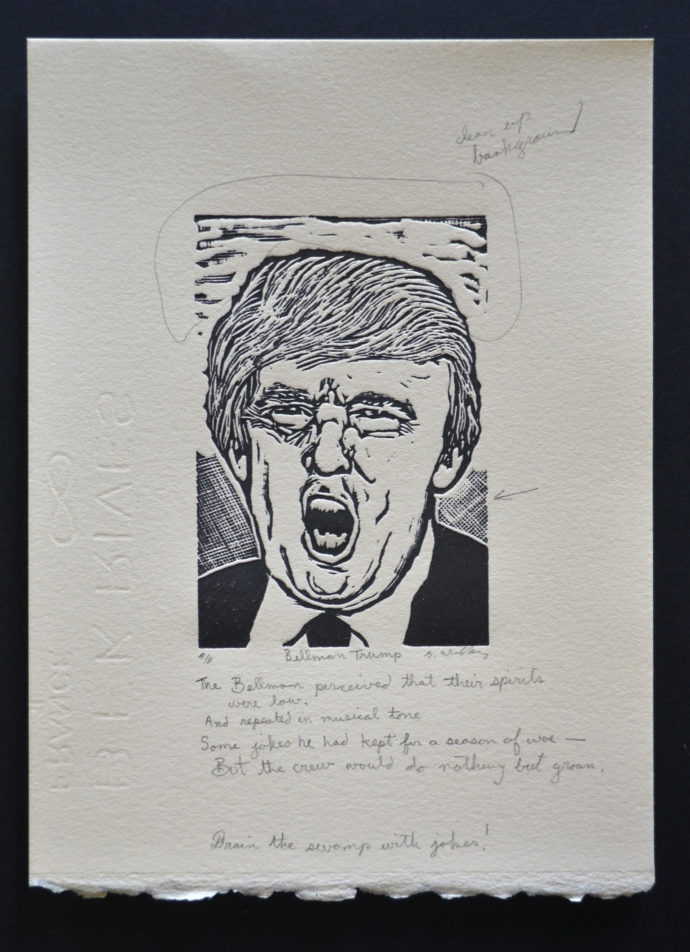

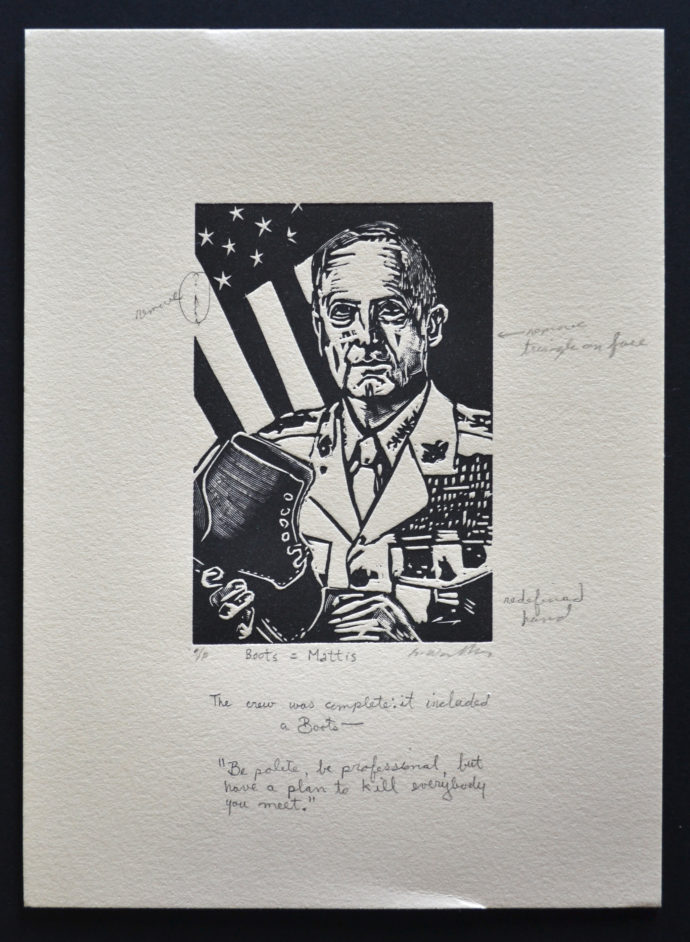

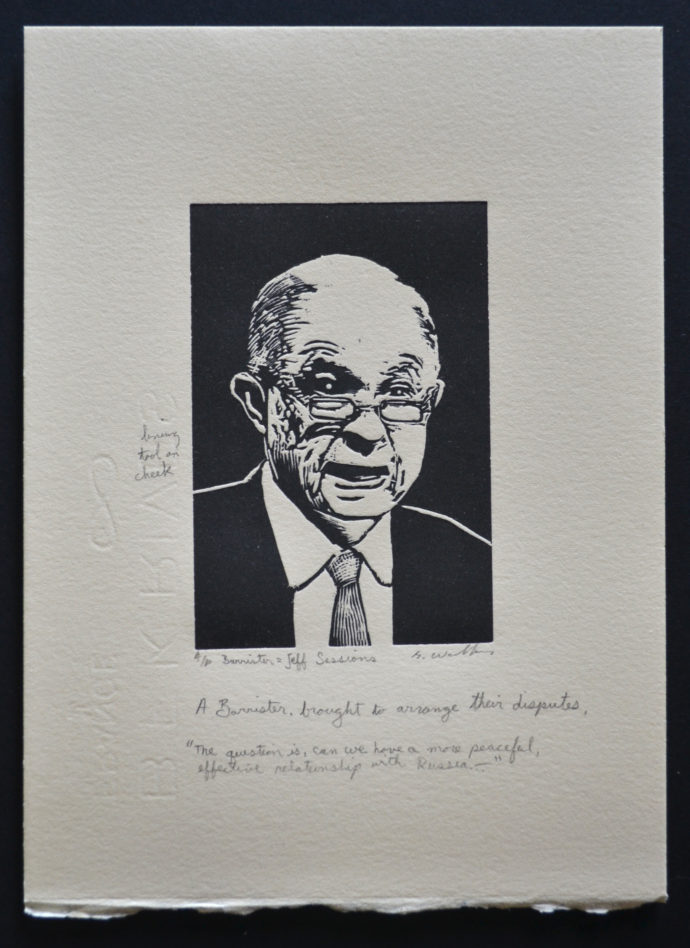

In short, George Walker is in very good, very crowded company. For his Snark crew Walker turned to faces from the Donald Trump administration, particularly the 2017 version. “Why Trump?” I asked him. His emailed response began: “When you read the poem and think of Trump’s cabinet, it’s hard not to see the parallels. The plot follows a crew of ten professionals trying to hunt the Snark with a blank map and a unqualified crew…. Some would describe the political arena in the USA as nonsense, and this is exactly the type of poem the Snark is.”

His answer was part of a Q&A that covered Walker’s affection for Lewis Carroll, a history of his own work illustrating Carroll books, why he chose to illustrate Snark, his working methods, and publishing plans for his Snark.

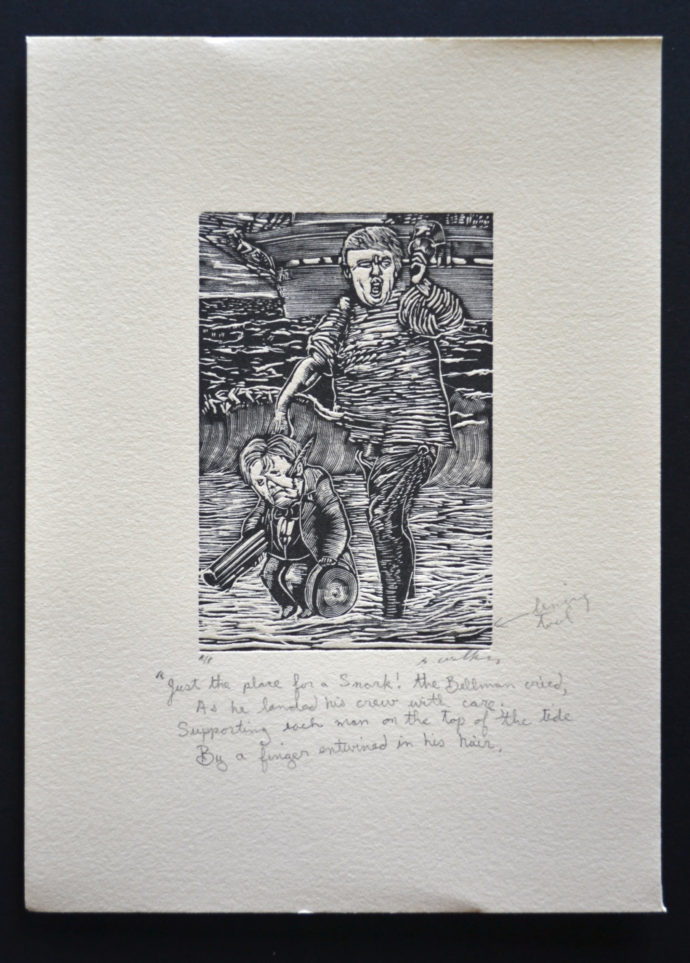

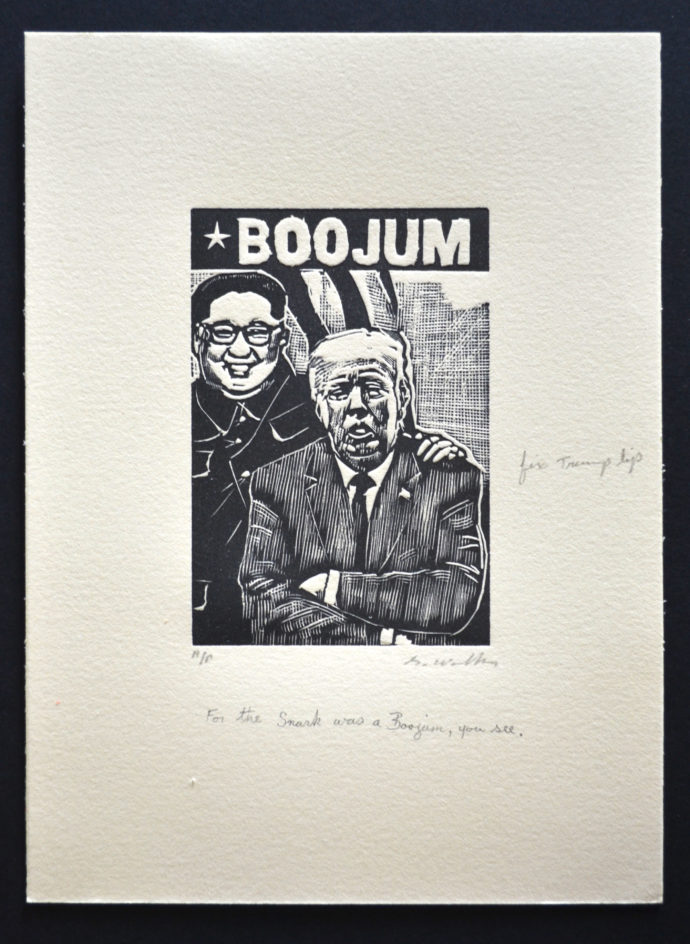

Interspersed are images of his “12 Preliminary wood engravings.” “Preliminary” indicates that these are working proofs. Most have penciled notations to point out where he thought he needed to make changes. Below the signature and title, Walker penciled in quotes from Snark and often added his own comments.

George Walker, “Bellman Trump,” wood engraving, image 4” x 2 3/4”, July 2018, a/p, with pencil annotations (Photo: Scott Ponemone)

What attracts you to Lewis Carroll and his literary output? What is The Cheshire Cat Press? Who are the principals? Was Cheshire the publisher of your other Carroll works?

I blame it all on Bill Poole (1923-2001) and Joseph Brabant (1925-1997). I was a first-year student in 1979 at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto when I met the professor and proprietor of Poole Hall Press, Bill Poole. When Bill met Joseph Brabant (a lawyer and avid Carroll collector), they formed the Cheshire Cat Press. I was invited to be the illustrator because I could make wood engravings that Bill could print on his press. We met monthly to have lunch together and review the work I had done and the text proofs Bill had hand printed. Bill would set the lead type and leave a space for an illustration for me to fill.

The object of this association was to publish in Canada by Canadian hands the first illustrated Alice in Wonderland and the first Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There. Joseph Brabant edited and provided the introductory text, I provided the wood engravings and Bill Poole hand set the type and printed the edition of 177 copies. During these monthly meetings I learned a great deal about Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a.k.a. Lewis Carroll. Carroll is known to us mostly as the author of the Alice children’s stories, but he was also a respected mathematician, logician, photographer and Anglican deacon. Carroll is noted for his facility at word play, logic and fantasy and wit.

Joe Brabant delighted in telling us details about his [Carroll’s] life and times. It was through Joe that I learned about all the Carroll societies in many parts of the world dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works and the investigation of his life. The first Cheshire Cat Press Alice was published in 1988 and Through the Looking Glass in 1998. In addition to these works the press also published a number of other Alice related texts such as Some Observations on Jabberwocky, Lewis Carroll and Alice Liddell and The Origins of the Poems in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. The project evolved into a eighteen-year collaboration between Joe Brabant (a member of the Lewis Carroll Society), Bill Poole, and myself.

When Joe Brabant passed away in 1997, he left his extensive collection of Carrolliana to the University of Toronto. His collection is now known as The Joseph Brabant, Lewis Carroll Manuscript Collection and consists of correspondence from Charles L. Dodgson (a.k.a. Lewis Carroll), many editions of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland from 1865 –1997, original photographs taken by Carroll, memorabilia, first editions, and Brabant’s notes and correspondence about the collection. Brabant’s collection is considered one of the finest private collections focused on Carroll to have been in private hands, and is the largest and most valuable single-author collection in the Fisher Library in Toronto.

I think my first reaction to being asked to participate in the Alice books is best illustrated by this quote from Alice:

“But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked.

“Oh, you can’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.”

“How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice.

“You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn’t have come here.”

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

George Walker, “Untitled,” wood engraving, image 4” x 2 3/4”, July 2018, a/p, with pencil annotations. This is Walker’s only snark image that makes reference to one by Henry Holiday. In the display of Holiday illustrations shown earlier, notice the similarity with the top left image. (Photo: Scott Ponemone)

What Carroll pieces have you illustrated in the past (dates, editions, etc.)

Alice’s Adventures in PUNCH 1864-1950, introduction by Edward Wakeling. (Cheshire Cat Press 2017). Andy Malcolm and I hand printed this book in a limited edition of 42 signed and numbered copies.

Illustrations for Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland illustrated by Harry Furniss with an introduction by Edward Wakeling (Cheshire Cat Press 2015). I restored these images from the original drawings made in 1907 from the archives of the Fales Library in New York City. Andy and I hand printed this limited edition portfolio in an edition of 66 copies signed and numbered.

Walker, George A, A Is 4 Alice (Erin, ON: Porcupine’s Quill, 2009), 26 wood engravings

—————., and Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Introduction by Alberto Manguel. (Porcupine’s Quill, 2011)

Brabant, Joseph A, Wouldn’t It Be Murder, 1st edn (Grimsby, Ontario: The Cheshire Cat Press, 1999) With four wood engravings and an epilogue by George A. Walker.

—————., Alice’s Adventures in Toronto. The Wood Engravings and Drawings for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Cheshire Cat Press 1991)

—————., and Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There. (Cheshire Cat Press 1998) illustrated with 94 wood engravings by George Walker, with an introduction by Andy Malcolm & George Walker. Printed by William Poole for the Cheshire Cat Press in Grimsby, Ontario. Limited to 177 numbered copies.

—————., and Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. with 96 wood engravings by George Walker, with an introduction by Joseph Brabant. (Cheshire Cat Press 1988) Printed by William Poole for the Cheshire Cat Press in Grimsby, Ontario. Limited to 177 numbered copies. First Canadian Edition

George Walker, “Trump & Pence,” wood engraving, image 4” x 2 3/4”, July 2018, a/p, with pencil annotations. (Photo: Scott Ponemone)

How have your Carroll illustrations been received by Carroll collectors?

Below are some reviews:

‘The classic Alice in Wonderland is known by all, but the story is off the wall enough that one’s interpretation may be different from another’s. Alice Adventure’s in Wonderland: Wood Engravings is George A. Walker’s own take with woodcuts as he illustrates Carroll’s famed story. Showing a unique skill in his interpretation, he captures a charm that’s been lost with the decline of woodcuts, and makes for a unique journey. Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland is a must for any fan of the story and unique art styles.’ —Midwest Book Review

Fanciful and eccentric, [George A. Walker’s] engravings cast Lewis Carroll’s classic fantasy fiction in a darker more sinister hue that will appeal to the inner child of many mature readers. —Robert Reid, The Record

Walker’s edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Cheshire Cat Press, 1988) announced forcefully his precocious talents as a printmaker and book artist. His enormously expressive woodcut illustrations paired with master letterpress publisher Bill Poole’s sensitive handling of type, printing and binding, comprised one of the finest hand-printed volumes ever produced in Canada. Alice has just been issued in a trade edition paperback by Porcupine’s Quill in Erin, Ont. —Tom Smart, “The great Canadian (graphic) novel”, Telegraph-Journal

Each image offered here provides evidence of its creation; there is a reminder, with each turn of the page, of the hand and thought that guided each groove. Walker’s ability to impress such great detail (as in the grain of both the fur of the Cheshire Cat, and the branch upon which he is perched) in a print made with woodblocks is remarkable…. At the heart of this book is the art of the book, pages kissed by poetic samples of Carroll’s writing and bound using artisan techniques onsite at The Porcupine’s Quill headquarters. It is a high-quality, collectible edition in which fans of the Alice stories, bibliophiles, and young readers will delight. —Patty Comeau, ForeWord Magazine

The Porcupine’s Quill has just released a wonderful new edition of Alice in Wonderland lavishly illustrated with wood engravings by George Walker and with a new introduction by Alberto Manguel. Following in the tradition of the Cheshire Cat Press edition published nearly 25 years ago by Bill Poole, George Walker and Joseph Brabant (one of the finest examples of a Canadian private press book), the story is as beautiful woven through the illustrations and design as it is through the magical words we are all familiar with. —Richard Coxford, Bytown Bookshop

George Walker, “S. Bannon = Butcher,” wood engraving, image 4” x 2 3/4”, July 2018, a/p, with pencil annotations. (Photo: Scott Ponemone)

What brought you to illustrate “The Hunting of the Snark”?

I’ve always been fascinated by the poem ever since I first read it. When Andy proposed we publish an edition of The Hunting of the Snark with illustrations by Byron Sewell, we thought it would be great if we could use the opportunity to publish two other versions of the book. One with Carte-de-visite images that Andy Malcolm has collected and one with wood engravings I would make.

The poem itself is clouded in mystery—Carroll intended it to be so. He has infused the poem with signs and symbols that scholars have been debating since its publication. Some say it is a poem about hubris, others declare it is a poem about death and is an allegory about tuberculosis. (His godson was dying of tuberculosis when he was inspired to write the poem.) Others believe it is a poem about tragedy, futility, folly of power, frustration, bafflement, nonsense and existential angst. Whatever one thinks about it, Carroll denied his poem had any meaning at all.

The Hunting of the Snark is one of the most inventive nonsense poems in the English language. It is composed of 141 stanzas in 8 cantos, which Carroll referred to as “fits.” In my opinion, the poem is an exercise of entropy in writing, a gradual abstraction in the form of words. That is attractive to me in and of itself!

Among his duties at Christ Church Oxford, Carroll supervised the Common Room, where faculty would gather for afternoon tea, or a glass of wine. He was responsible for the system of ordering and tracking the supplies including a stock of wine with more than 20,000 bottles. He wrote a pamphlet in 1886 about his system titled, Three Years in a Curatorship by One Who Has Tried It. It records his attempts to keep the cellars well supplied and efficient. Here is a quote from the pamphlet, “If you want to inspire confidence, give plenty of statistics it does not matter that they should be accurate, or even intelligible, so long as there is enough of them.”

George Walker, “The Mooch-Maker of Bonnets and Hoods,” wood engraving, image 4” x 2 3/4”, July 2018, a/p, with pencil annotations. (Photo: Scott Ponemone)

What is the significance of the number 42 in Snark?

The Baker has 42 boxes of luggage, and Carroll was 42 when he wrote Snark. We are printing 42 copies of the limited edition. When we publish our edition in 2019, my age, and the age of Carroll when he wrote the poem will add up to 100. The 100th line of the poem reads. “They are merely conventional signs!” This is a comment on the blank map the Bellman is using to navigate. A map to nowhere!

Carroll was a follower of the mathematician Agustus De Morgan, and he owned many of De Morgan’s books. One title by De Morgan is A Budget of Paradoxes (Longman Green & Co. 1872) in which Carroll has made many marginal notes. In one of these notes he tries to solve the problem: “I was x years old in x2 ” Carroll has written the number 42 in the margin beside this problem. The Oxford dictionary describes a paradox as, “A statement or tenet contrary to received opinion or belief; often with the implication that it is marvellous or incredible; sometimes with unfavourable connotation, as being discordant with what is held to be established truth, and hence absurd or fantastic; sometimes with favourable connotation, as a correction of vulgar error.” Oddly Carroll’s other publications, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and his supernatural poem Phantasmagoria contain references to the number 42. Other writers have referenced this number too! Douglas Adams, in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, states that the “Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything is 42.” According to the book, it was calculated by an enormous supercomputer named Deep Thought over a period of 7.5 million years. Unfortunately, Adams wrote, no one knows what the question is.

And finally 42° is the critical angle (rounded to whole degrees) for which a rainbow (from the direction opposite the light source) appears. Everyone knows that rainbows are not real objects and can never be touched—accept in dreams!

He had forty-two boxes, all carefully packed,

With his name painted clearly on each:

But, since he omitted to mention the fact,

They were all left behind on the beach.

George Walker, “Sarah Sanders = The Baker,” wood engraving, image 4” x 2 3/4”, July 2018, a/p, with pencil annotations. (Photo: Scott Ponemone)

Did Holiday’s illustrations make comments on the political situation in 1870s England? How so?

The short answer is no. However, one could argue that some of the characters bear a resemblance to prominent political and famous figures of the time. For instance, the Banker reminds some of the British M.P. John Bright (1811-1889) and the Bellman looks a bit like Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892). But Holiday did not set out to point at any political figures of the time, and Carroll did not intend the poem to poke fun at politicians.

Carroll is famous for his logical nonsense and the Snark poem is part of this. It is well documented that Carroll exerted an obsessive control over his illustrators. Both John Tenniel (the Alice books) and Harry Furniss (Sylvie and Bruno) had disagreements with Carroll over their work. Holiday was a close friend and an admirer of Carroll; yet Carroll himself confessed that this collaboration was fraught with difficulty. Was there a political comment being made in the Snark? The short answer is no; however, one can read into Carroll’s linguistic formations and Holiday’s character representations that, one may argue, contain conscious and directed symbolism both to events of the time and the characters that influenced the Victorian era. This can be interpreted as a political construct, but it is very general and vague on details. Henry Holiday was not apolitical. He was a socialist and his wife Kate worked for William Morris. Holiday is associated with the Pre-Raphaelite school and his images for the Snark may have been influenced by the political magazine Punch, which John Tenniel (illustrator of the Alice books) worked for. Carroll wanted his characters to be grotesques (large head caricatures) like the illustrations in the Alice books that John Tenniel illustrated. Grotesques were popular in political satire publications of the time such as Punch and the Illustrated London News. Caricatures were created by artists to ridicule public figures and politicians. Some popular artists working in this field that Carroll would have known of are: George Cruikshank, Honoré Daumier and William Hogarth.

George Walker, “Mnuchin = Banker,” wood engraving, image 4” x 2 3/4”, July 2018, a/p, with pencil annotations. (Photo: Scott Ponemone)

You choose to make President Trump and White House officials your 21st-century Snark line-up. Why them? How is that decision in keeping with Carroll’s poem and illustration history?

When you read the poem and think of Trump’s cabinet, it’s hard not to see the parallels. The plot follows a crew of ten professionals trying to hunt the Snark with a blank map and a unqualified crew. We are not told what a Snark looks like, and none of the crew have experience hunting Snarks. But the Bellman says in the first fit, “Just the place for a Snark! I have said it twice: That alone should encourage the crew. Just the place for a Snark! I have said it thrice: What I tell you three times is true.” This is why I chose Trump to be the Bellman. Trump’s notion of truth is, at best, flawed. We are told the Snark is an animal that may turn out to be a highly dangerous Boojum. But we are not told what a Boojum is. I made the Boojum Kim Jong Un with his arm around Trump. And curiously the only one of the crew to find the Snark—the Baker—quickly vanishes, leading the narrator to explain that it was a Boojum after all. Ummmm—it’s like the people in Trump’s cabinet who vanish! Some would describe the political arena in the USA as nonsense, and this is exactly the type of poem the Snark is.

George Walker, “Broker Reince Priebus,” wood engraving, image 4” x 2 3/4”, July 2018, a/p, with pencil annotations. (Photo: Scott Ponemone)

What is your working method for creating/selecting the faces in your Snark menagerie? You use photos, no? How do you transfer the photos onto the blocks? Then you paint on changes to the images?

I use a combination of techniques that include transfers to the wood block, drawing directly and indirectly and allowing the engraving tools to suggest patterns and textures. I use photos for reference and to capture likeness. For the transfer onto the end grain maple wood, I use a non-toxic synthetic product known as Estisol 150. First the image is printed out of a computer using a toner based laser printer. Next the block is wiped with a small amount of Estisol. Then I anchor the trimmed laser copy to the block with masking tape and carefully rub the back of the paper until the toner transfers to the block. I let this dry for a day, and then I use a black marker to draw into the transfer.

George Walker, “Boots = Mattis,” wood engraving, image 4” x 2 3/4”, July 2018, a/p, with pencil annotations. (Photo: Scott Ponemone)

I’m immensely honored that you would make me a gift of your “12 Preliminary wood engravings” to Snark. Why did you do so? Why would you want me to use these images in a blog? Wouldn’t my doing so somehow preempt your planned edition?

I wasn’t going to make a folio of the preliminary engravings! But when you saw what I was doing and expressed an interest in seeing the printed images, I thought, I’ll print some sets and send one of them to you. I only made 8 folios. I needed to print proofs to send to people who are helping me on the project. Mark Burstein is writing the introduction, and we needed to send him a set too. I also wanted to see what people thought of the project before we printed the edition. I really enjoy reading your blog about artists and their work, and I thought you might be interested in seeing how this project evolves.

What are your edition plans for Snark? Expected publication date and edition size?

42 signed and numbered copies full bound in cloth with a slipcase. We are hand printing—that takes time—we are hoping to have them available for the spring of 2019.

George Walker, “Barrister = Jeff Sessions,” wood engraving, image 4” x 2 3/4”, July 2018, a/p, with pencil annotations. (Photo: Scott Ponemone)

You’ve told me that your Snark wouldn’t be published until 2019. Are you at least somewhat afraid the timeliness of your images wouldn’t be overtaken by then?

Not really. We are only making 42 copies and expect them to sell quickly to collectors. I don’t think it matters when it appears—and, ye,s time overtakes everything in the end. I reckon looking back helps us to see forward. I wanted this version of the Snark to have some contemporary references. I hope people will remember what it was like living under the Trump years; however, I think memory is a temporary thing. Here’s a stanza from the Snark poem that reminds me of Trump:

There was one who was famed for the number of things

He forgot when he entered the ship:

His umbrella, his watch, all his jewels and rings,

And the clothes he had bought for the trip

George Walker, “Trump & Beaver,” wood engraving, image 4” x 2 3/4”, July 2018, a/p, with pencil annotations. (Photo: Scott Ponemone)

What other illustration projects are you currently pursuing? For Cheshire or Firefly Books? (Your position at Firefly?)

For my personal projects, I am working on another wordless narrative about the life and times of the Hollywood star Mary Pickford. She was the queen of the silent film era. I also have an Edgar Allan Poe book and a chapbook about a medieval doctor by Martin Llewellyn that are in development. The Cheshire Cat Press is publishing three versions of the Snark, one with art by Byron Sewell, one with Carte–de–visite that images that Andy Malcolm has collected and the third is my Snark. We are in discussions about future projects for 2020 and beyond.

I also work as a creative director at Firefly Books Ltd. I do some illustration, design, cartography and info-graphics for various titles on our list. One of the most recent illustration jobs was a series of ink drawings for the new Firefly edition of, 500 Words You Should Know by Caroline Taggart. Firefly publishes hundreds of titles per year.

As for what might be next….

“If you don’t know where you are going any road can take you there”

― Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

George Walker, “Untitled,” wood engraving, image 4” x 2 3/4”, July 2018, a/p, with pencil annotations. (Photo: Scott Ponemone)

Another wordless novel/biography? If so, what/who is the subject of such an effort? And why the choice?

Yes! This one is about Gladys Louise Smith (1892-1979), known professionally as Mary Pickford. She was a Canadian-born (Toronto) film actress and producer. Pickford, along with her husband, Douglas Fairbanks, were the co-founders of both the Pickford-Fairbanks Studio and, later, the United Artists film studio with Charlie Chaplin and D.W. Griffith. Mary Pickford is one of the original 36 founders of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which award the annual Oscars. She is remembered as Americas Sweetheart and one of the early pioneers of Hollywood in the silent film era.

I like the idea of creating a wordless biography of a silent film star.

For the record where do you teach? What do you teach there? And your position there?

I am an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Art at the Ontario College of Art and Design University in Toronto. I teach book arts courses such as bookbinding, letterpress typography, the book as art, relief printmaking and whatever the Dean tells me to teach.

George Walker and his wife Michelle relaxing in the cottage. (Photo: Scott Ponemone)

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/george-walker-cutting-at-the-cottage/trackback/

Thank you, Scott (and George) for this wonderfully written inside peek at the creative process of rich art form, delicious rhyme, and chisel-sharp portrayal of the ridiculous. I can smell the wood chips and ink and am already contemplating a woodcut with a punch.

Thanks Scott, love this recounting and getting to see the process and insight into the work. Given George’s current interest in Mary Pickford, thought he might be interested ((for general atmospherics) in the current season of the “you must remember this” podcast (Fact checking hollywood babylon)- episodes 1 and 2 have focused on the Gish sisters, Olive Thomas (who was married to Mary Pickford’s brother, Jack)

Thank you for this interview. George Walker’s Snark is outstanding. It’s very appropriate too. Snark+Trump, it had to happen!

best regards from Munich

Goetz

Brilliant, relevant and timely. Are you ever in London? If so, the Lewis Carroll Society would love you to give a talk on your work.

This promises to be a wonderful book, and it would certainly find an audience beyond the 42 hand-printed copies that are planned.