Frans Masereel: Workers’ Paradise in 1939 Europe

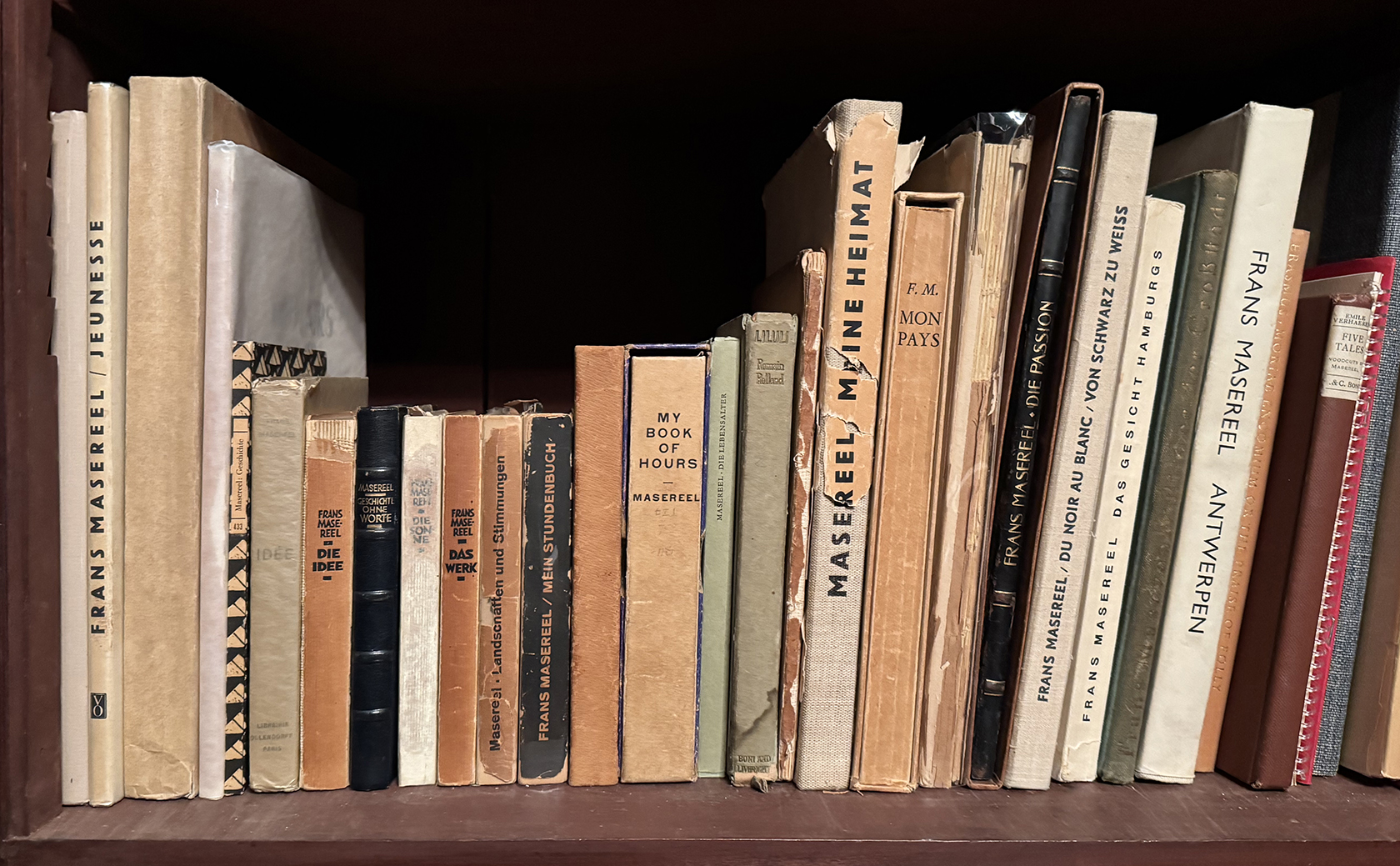

Shelf devoted to Frans Masereel, both his wordless narratives and the books he contributed illustrations to. (Ponemone photo)

Introduction

As my bookshelf attests I’ve a great affinity for the Flemish artist Frans Masereel (1889-1972) and his books, most of which were wordless narratives told in relief prints. I find these books visually stunning and his dystopian stories quite affecting. His earliest books appeared in 1917. They greatly influenced Lynd Ward (1905-1985), an American whose first wordless narratives–Mad Man’s Drum and Gods’ Man–were published in the late 1920s.

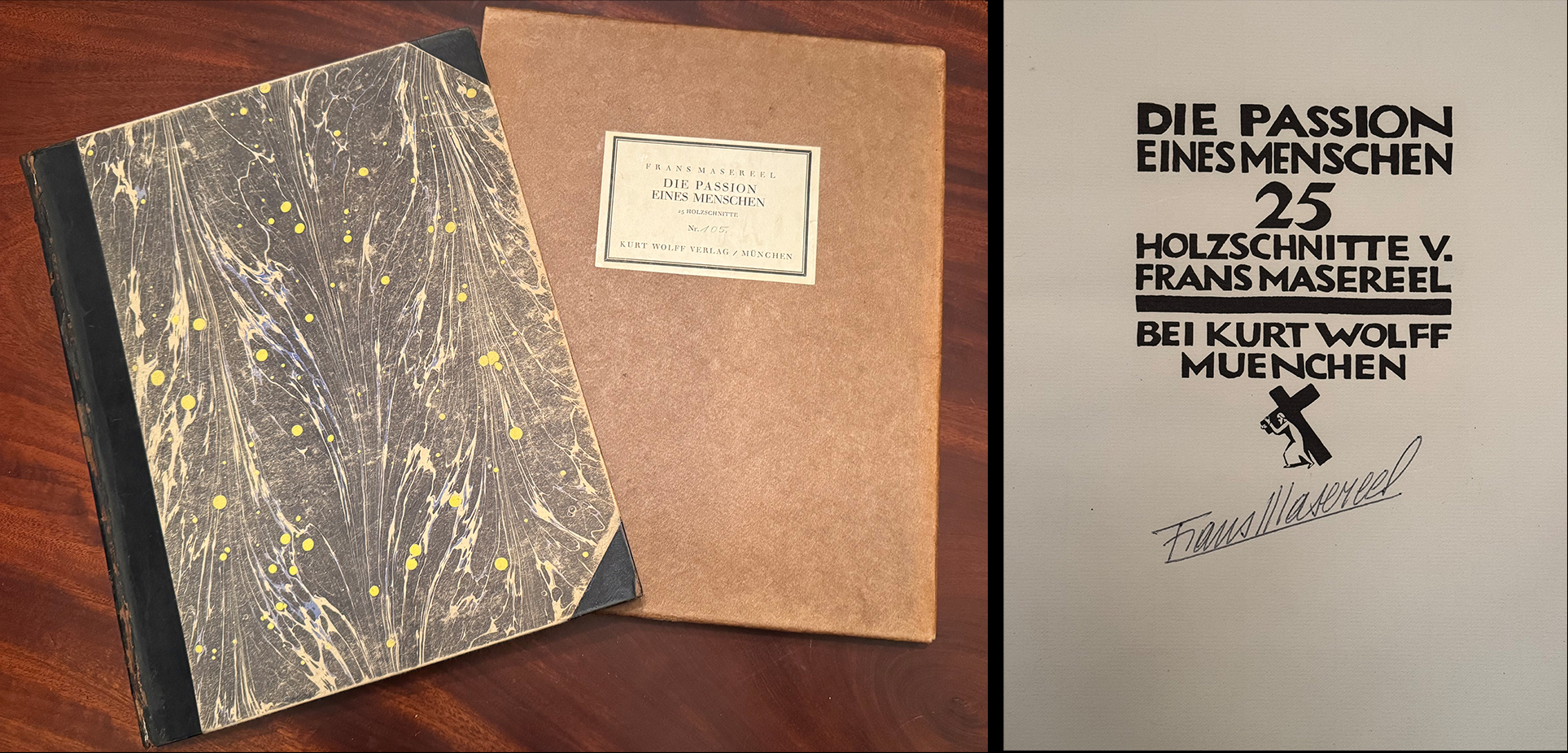

As has often been the case as a collector, my first Masereel acquisitions around 1980 were trade editions, like Mein Studenbuch and Landschaffen und Stimmungen (the short volumes to the left of center in the row) printed in Germany by Kurt Wolff. Lately I’ve been fortunate to add first signed editions of Souvenirs de mon Pays (Memories of my Country), Die Passion eines Menschen (The Passion of a Man) and Du Noir au Blanc von Schwarz zu Weiss (From Black to White from Black to White). It’s the purchase of the latter book that is the catalyst for this post.

I first bought a trade edition (one of 2000) of Du Noir au Blanc von Schwarz zu Weiss via eBay some 15 years ago. Its condition with the spine off and foxing throughout didn’t match the online description, but I kept it. Then this year the above signed edition of just 100 copies appeared on AbeBooks.com from a German bookseller.

Once it arrived I read this 1939 book page by page, black-and-white print by print. And for the first time its message sunk in. It was a fantasy of a workers’ victory over Capitalism. My first reaction was to think that Masereel must have had a blind eye toward the imminent outbreak of World War II. I needed to read Roger Avermaete’s essay in his book Frans Masereel (Fonds Mercator/Rizzoli International, New York, 1977) to learn more about the artist and his politics to give some context to the book’s production. It also helped that Masereel wrote a one-page foreword.

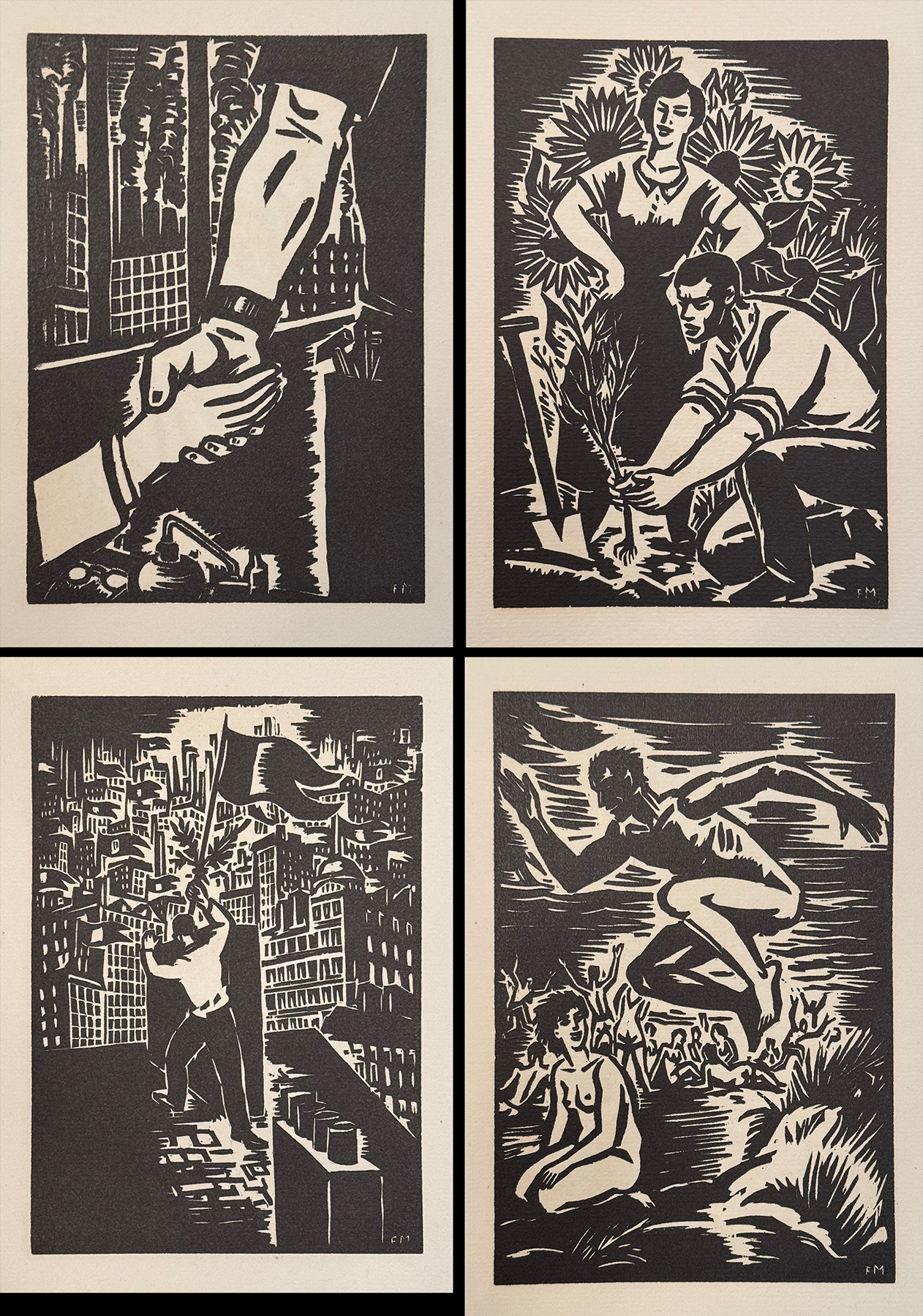

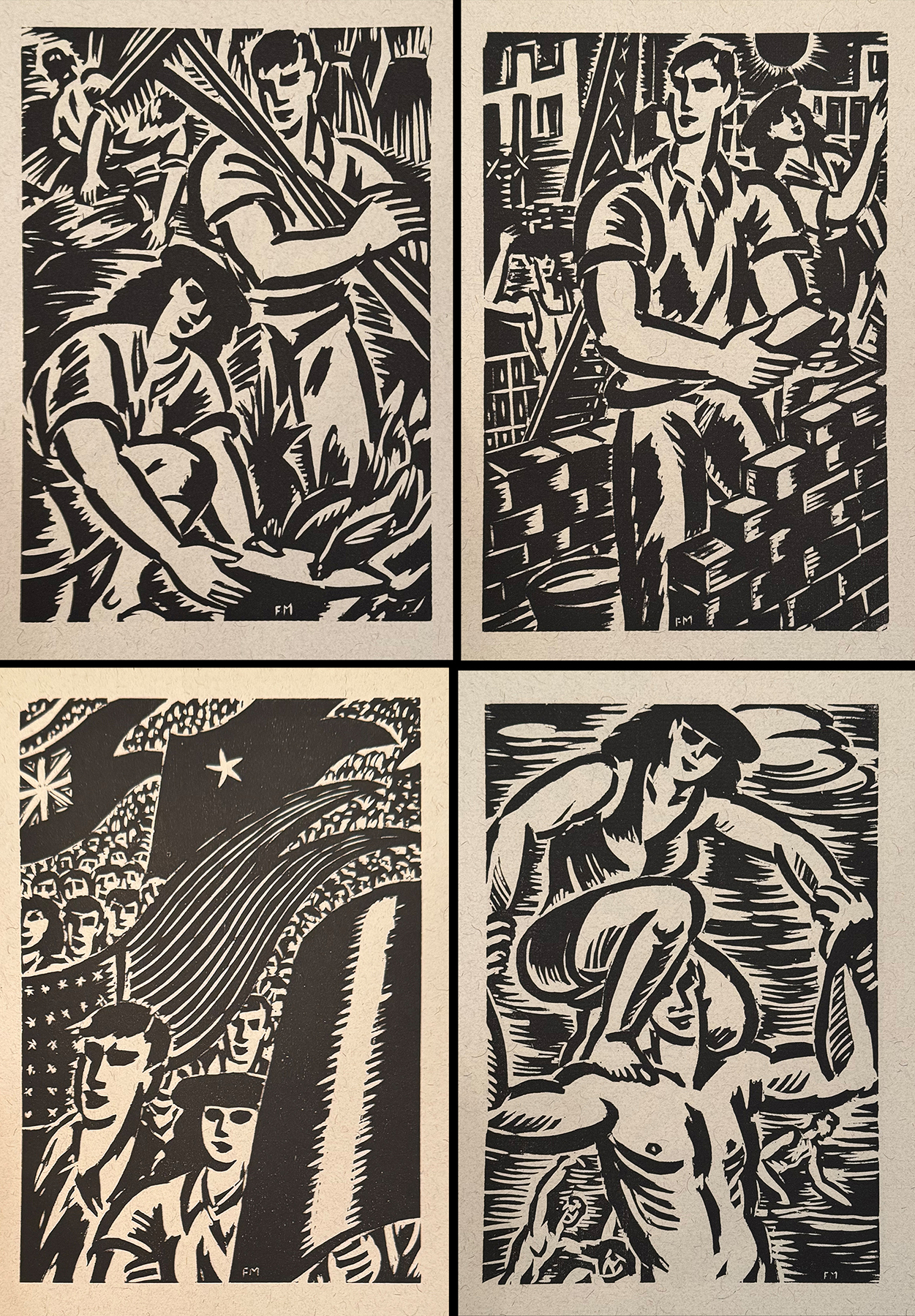

A summary in 16 woodcuts

But first I’ve chosen 16 plates from the book’s 57 to give ART I SEE readers a sense of the storyline.

Read each of the four-print groupings clockwise starting at the top left.

Starting in the pristine jungle, Masereel imagines 1900 European civilization decimating Eden to build a metropolis with workers like the man high on the I-beam taking all the risks.

These plates illustrate the arrogance of the industrial magnates, the separation of the classes and the monument the ruling class erected to confirm its control.

Here the thinking man acknowledges the brutality and unfairness Capitalism, then awakens the workers who defeat the Capitalists.

After the revolution workers shake hands, a bucolic life returns and flags fly everywhere.

In his foreword Masereel wrote:

“Then, I tried to present, without prejudice, a human-made creation story in 57 images. It begins in the jungle; the wild animals flee from man, who arrives with tremendous hunger and possessiveness. In order to rule, he begins to destroy; he builds in order to exploit, to enjoy. ‘Man is a wolf among wolves.’ On the one hand, he creates abundance; on the other, misery, despair, hatred. The logical consequence: the awakening of conscience, butcheries, rebellions. Let us think of what has happened in recent years. My work ends with the hope for a more beautiful, happier life and the great human reconciliation in the justification of work.”

Masereel’s early years

Here I parse Avermaete’s essay and quote some passages.

Masereel was born into a well-to-do Catholic family. His father died when Frans was 5. His mother then married “a Dr. Lava, a liberal-minded man who was influential in modifying the strict Catholic outlook of the Masereels. This was a period of the rise of socialism. In Belgium many sons of middle-class families felt drawn to the new doctrine…. Among intellectuals, liberalism tended to shade into anarchism.“

In 1910 he left for Paris with Pauline Imhoff, who was to become his wife. In August 1914 at the outbreak of World War I they left for Ghent. He avoided military service thanks to drawing of lots–”a wretched system of recruitment was still practiced in Belgium.”

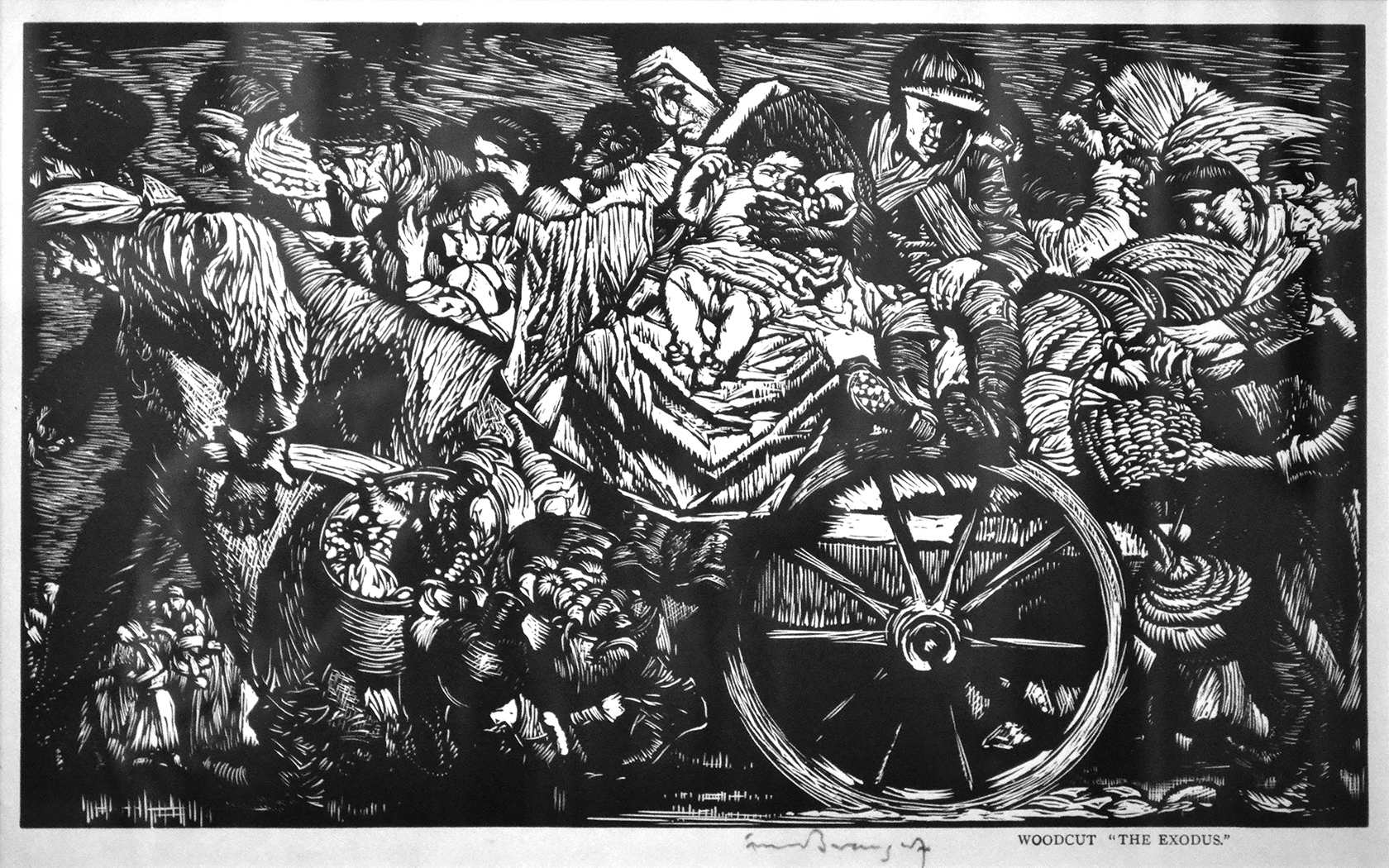

This is the type of scene Masereel may well have witnessed in Belgium after the war. It was created by English artist Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956), who was born in Bruges. “The Exodus,” 1919, wood engraving, 7 1/2″ x 12 1/2″ (19.3 x 32 cm)

After the war he would return to Paris. “Before he left Belgium he saw in Termonde the first real scenes of the war: the wretched stream of refugees, wounded soldiers and demolished houses. He was never to forget them.” But, according to Avermaete, his early work didn’t show it: “The artist was against war, we know, but only because he said so. This was an attitude that went back to his childhood, rather than the result of personal experience.”

Avermaete provides a particularly good description of Masereel’s deftness with pen and ink when it came to capturing an image quickly:

“He bacame a regular contributor to the journal La Feuille, which started in August 1917 by Jean Debrit. For this work he adopted a method which was to have an enduring influence on his style. With only a couple of hours to prepare and deliver his daily drawing–just enough time to read the news and obtain his subject-matter–he took up brush and Indian ink. The strong contrasts of black and white which resulted produced powerful effects which would have been impossible to achieve with pen or charcoal. While in his first brush drawings he emphasized the fate of soldiers sacrificed, his thoughts soon turned to those he considered responsible for this calamity. His work became an accusation against those in power–the politicians, the magnates, the arms manufacturers–all those who built their fortunes on the sufferings of the defenseless. This accusation, which he was to repeat daily a thousand times, represents a point of crystallization on Masereel’s work.”

Heroic tragedy

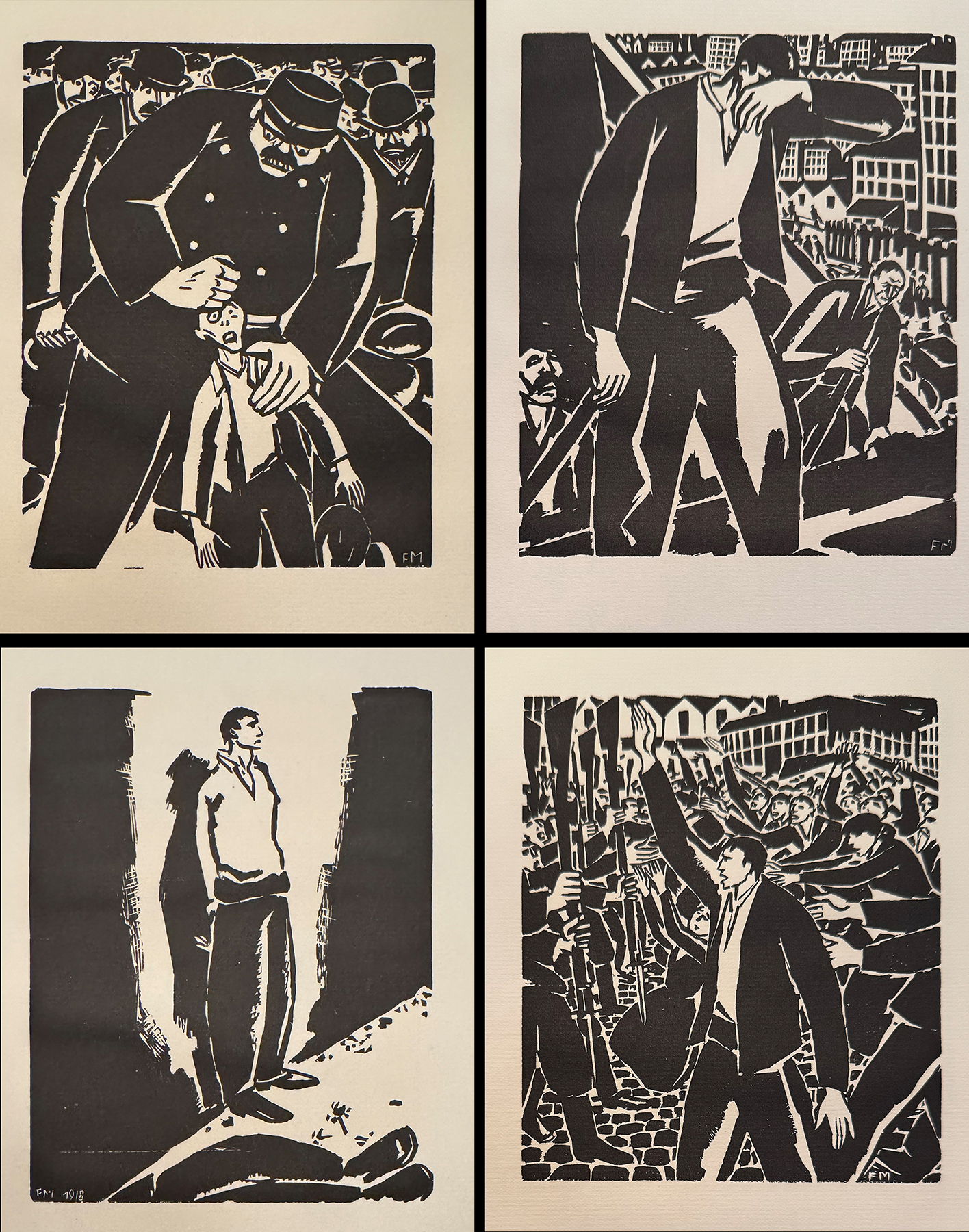

Masereel vividly illustrated his distain for “those in power” in his wordless narrative first published in Geneva in 1918 as La Passion d’un Homme. The first German edition by Kurt Wolff in Munich came out in 1921 as Die Passion eines Menschen.

Here are 4 of the 25 woodcuts that comprise Die Passion eines Menschen. In it the protagonist suffers a harsh upbringing, exhausting labor, command of a brief uprising and death by firing squad. The lone man has a no chance against “those in power”–in sharp contrast to what a lone man would accomplish in Du Noir au Blanc von Schwarz zu Weiss, a book published 21 years after Die Passion eines Menschen.

During the heart of the Depression the American artist Lynd Ward captured the same futility in his 1932 book Wild Pilgrimage. A lone man, trying to find a place in the world for himself, leaves a dismal factory town, briefly finds comfort as a farmer only to return to the mill where he dies during a strike for workers’ rights.

The allure of Russia

In 1932 he attended in Amsterdam a world congress against war and fascism. Avermaete wrote that Masereel “came back disillusioned, ‘I don’t regret having put myself out to go there, but I was very disappointed by the organization and by the attitude of the communists. I thought we had come to work and all they did was sing, yell and palaver.’ ”

Avermaete further wrote:

“Events in Germany disturbed him deeply. Many friends took the road to exile. His work was far from contenting him. He wrote to Henry van de Velde at this time: ‘But technical questions are on the whole secondary. A question that bothers me greatly is knowing what an artist should do in today’s world. A purely self-centered attitude cannot satisfy me, nor direct action either….’ ”

Avermaete then quotes a letter Masereel wrote to Roman Rolland: “People don’t give a damn about art today, any more than they do about the rest. What a mess the world is in! The only thing that is clear is that a fine little war is in the offing!”

Like many of his fellows leftists, Masereel looked toward Russia for answers.

In April 1935 he traveled to Moscow and, according to Avermaete, was given “a triumphal welcome.”

On 7 May 1935 he wrote to Rolland: “The First of May celebrations are something tremendous. Everything here is tremendous, even, alas! the lack of punctuality. In twenty-five years it will be a country which will have nothing to ask from others.” On his return home he again wrote to Rolland: “I came back from Moscow yesterday altogether enchanted by my stay in the USSR.”

He returned in 1936 with his wife for three months traveling widely. Of this he wrote: “After what I’ve seen, my admiration for the effort of the men who set in motion the change in this country continues to grow.”

It was in the glow of all that admiration that he created the 57 images that became Du Noir au Blanc von Schwarz zu Weiss.

However, Avermaete wrote: “His hopefulness was checked by news of repressive measures in Soviet Russia. He was disconcerted and could not understand, and yet, in spite of everything, he would not lose courage, he would not bend. ‘This disaster of arrests and executions as you said is terribly worrying, but that doesn’t alter the fact that the cause–often in spite of men themselves–is good and we remain faithful to it, which is not the case with many intellectuals hereabout.’ ”

And the signing of a non-aggression pact between the Soviet union and Nazi Germany in 1939 was a shock.

The War

“At their outbreak of war,: Avermaete wrote, “Masereel at once abandoned his pacifism. During the 1914-1918 war he kept aloof, as a pacifist must, because the conflict was not concerned with any ideal, but was a settling of accounts among capitalist powers…. In 1939 his state of mind was altogether different. As he saw it, all human values were threatened, and so, despite his horror of violence, he judged defense to be not only legitimate but necessary. His aversion for Nazism was greater than his disgust for war.”

He expressed his “aversion for Nazism” and depicted the horrors of World War II in a series of wordless narratives composed of reproduced drawings. He didn’t have the luxury of cutting woodcuts and getting them printed because he was on the run. He fled Paris a few days before occupation , eventually arriving in Avignon.

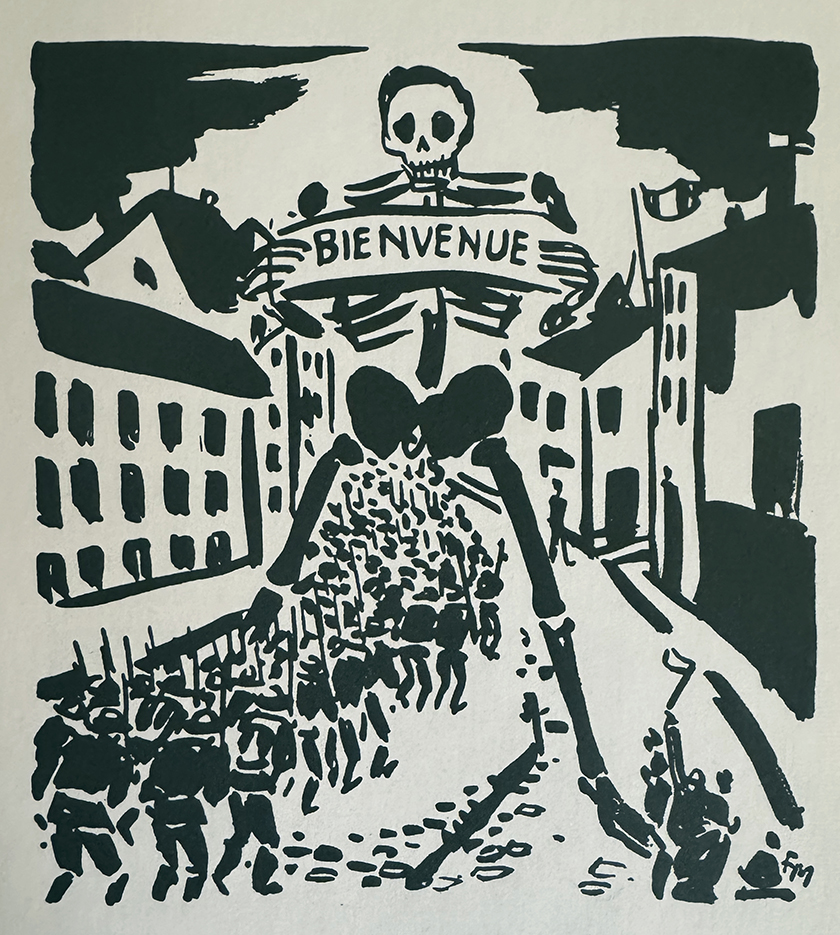

In early April 1941 he was working on Danse Macabre, “a series of drawings soon to be published; then on Destins 1939-1940-1941-1942, and La Terre sous le Signe Saturne (The Earth under the sign of Saturn).”

In Danse Macabre (Pantheon Books Inc, New York, 1952) Death as a skeleton is at first joyous over his ability to reek mayhem but eventually becomes taciturn over the ruins he leaves behind. Eventually Death profits from the universal hunger that war created by selling bread.

In an insert to the book the publishers wrote:

“This series of twenty-five drawings is the first creative work of art which has come out if the immediate experience of this war and which meets the intensity the tragic grandeur of world disasters.

“In a letter of September, 1940, to the publisher of this book, Masereel in his simple manner describes his personal share in the tragedy of our times: ‘We have lived through tragic days, having left Paris on foot! We have walked for nearly 300 miles, have been bombed and machine-gunned several times a day, and finally got stranded in an old mill, where we lived for a month on a litter of straw. Now we are with friends, which is somewhat more comfortable. I cannot paint as there is nothing to paint with. So I am now working out in black and white skeletons which I made during the retreat, or rather the debacle!’ “

The Germans arrived in Avignon at the end of 1943. Many were arrested; shops closed. He found refuge in Lot-en-Garonne. Avermaete wrote: “It was in a lonely part of the country near Monflanquin. Not far from there Masereel was taken in by peasants, in the small mill of Bezès.”

La Colère (Herbert Lang, Berne, 1946) was composed of 20 drawings that Masereel created from 1944 to 1946.

Herbert Lang in Berne also published Remember from 26 drawings Masereel made from 1944 to 1946. He graphically depicted the horror of the Holocausst.

Masereel stayed near Monflanquin until 1949 “not knowing where else to go. His house in Equihen had been totally destroyed, and he had lost almost everything he owned: the major part of his library, his collections, rugs, letters and documents, some twenty paintings, numerous sketches and drawings. In addition to which, his Paris studio had been broken into.”

Liberation and Rebirth

Avermaete wrote: “In 1948 he made his first visit to Belgium since the end of hostilities. His impressions were not favorable. ‘It’s a country morally americanized. There’s no room for anything but “gangsterism” and “pin-up-girls.” ‘ ”

In 1948 Verlag Sprecht, Zurich, would publish Masereel’s book Jeunesse (Youth) with 22 woodcuts in the spirit of rejuvenation. The scenes of rebuilding and replanting and cavorting mirror the workers’ paradise he promised in Du Noir au Blanc von Schwarz zu Weiss. It only took fours years of war to get there, and Capitalism survived.

Masereel’s romance with Communism continued despite the establishment of the Iron Curtain imposed on Eastern Europe by the Soviet Union.

“Living in a capitalist society,” Avermaete wrote, “he lashed out at men in power. His success in the Communist countries, in China and in Russia, is readily understandable. Because they had liberated themselves from capitalism–which to him was the gangrene of civilization–he felt irresistibly drawn to them, and this sympathy was reflected in 1956 in two journeys, first to Russia, where visible improvement in living conditions overjoyed him, then to China, where he was welcomed with especial warmth.”

As a compliment to his China journey he created Souvenirs de Chine (China Memories) with four color reproductions and 16 drawings, published by Edition Leipzig in 1961.

★ ★ ★

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/frans-masereel-workers-paradise-in-1939-europe/trackback/