Fables: Erich Glas’s prints add to genre

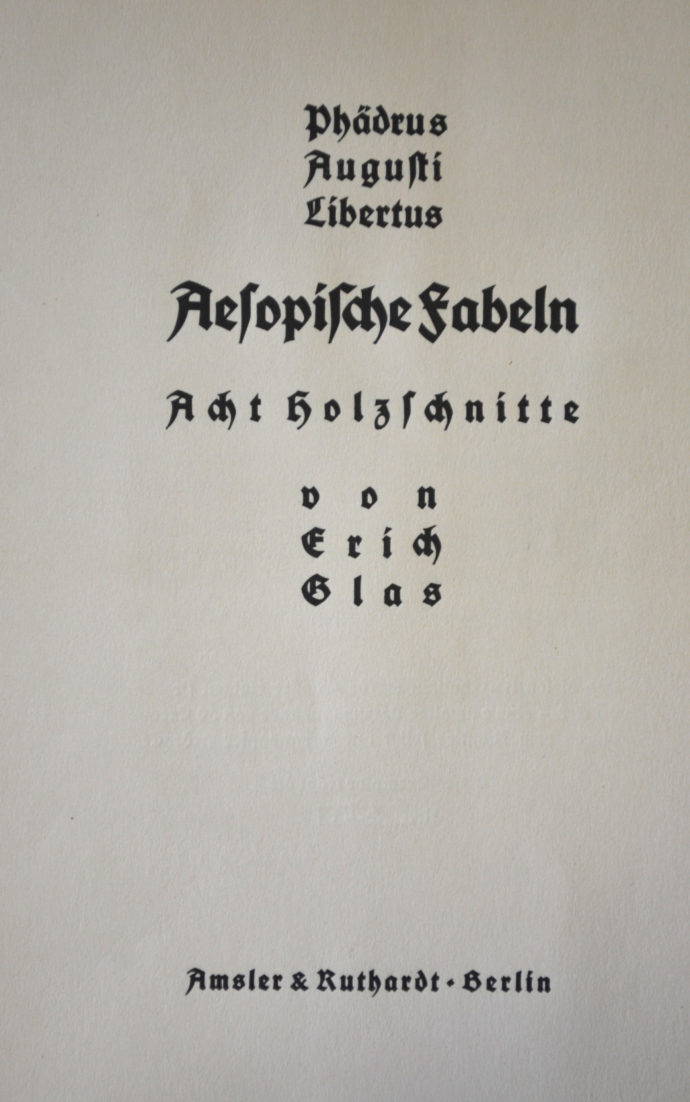

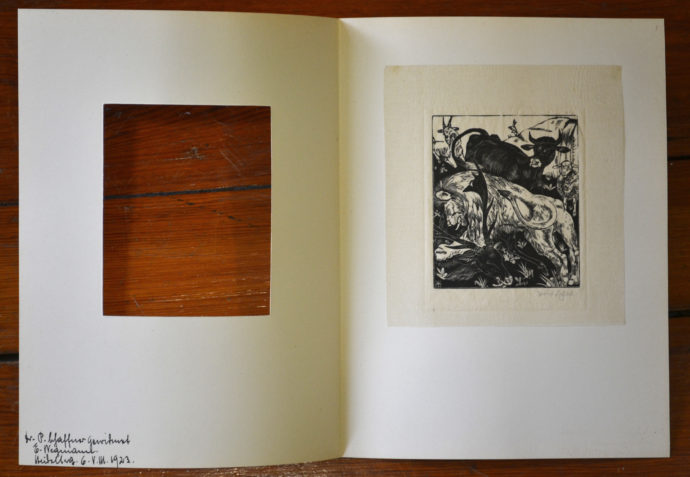

The opened portfolio of “Phaedrus Augusti libertus: Aesopische Fabeln”

INTRODUCTION

One of the benefits of being a daily watchdog of eBay offerings is that occasionally an item that is completely new to you comes up for auction. This was the case a few months ago with a portfolio of wood engravings entitled Phaedrus Augusti libertus: Aesopische Fabeln. (The title essentially translates as Aesop Fables, by Phaedrus, who was freed by Augustus.) The suite of eight prints and an illuminated initial are signed by Erich Glas. I immediately found the prints to be imaginatively designed and beautifully engraved. Moreover, fable illustrations hold a fascination for me. I already had four books of illustrated fables.

So my next action was to start an online search. Who was Phaedrus? Who was Erich Glas? Was this eBay offering unique? Since only two of the prints were posted on eBay, what did all eight wood engravings look like? And what were the eight fables that Glas illustrated?

Phaedrus and fables

According to the Cambridge History of Classical Literature (as offered online by library02.com), Phaedrus was a “Thracian slave, manumitted by Augustus,” His dates were more or less 8 B.C. to 50 A.D. “Remnants of five books of Aesopian fables in iambic senarii, pubd at intervals between c. A. D. 20-50. … The codex Pithoeanus transmits ninety-four fables and some seven other pieces, and some thirty other items are added by the appendix Perottina (a 15th-c. transcription by N. Perotti from a MS apparently less truncated than P). But the collection is still far from complete.”

Pheadrus was the author of the verses, but not the originator of the fables. So then who was Aesop? Another online source (https://www.ancient.eu/article/664/aesops-fables/) presents an article by John Horgan: “Aesop’s Fables.” It begins: “Written by a former Greek slave, in the late to mid-6th century BCE, Aesop’s Fables are the world’s best known collection of morality tales. The fables, numbering 725, were originally told from person-to-person as much for entertainment purposes but largely as a means for relaying or teaching a moral or lesson. These early stories are essentially allegorical myths often portraying animals or insects e.g. foxes, grasshoppers, frogs, cats, dogs, ants, crabs, stags, and monkeys representing humans engaged in human-like situations (a belief known as animism).”

But Horgan doesn’t credit Aesop with founding the genre. He writes: “The origins of the fables pre-date the Greeks. Sumerian proverbs, written some 1,500 years before Christ, share similar characteristics and structure as the later Greek fables. The Sumerian proverbs included an animal character and often contained some practical piece of advice for living.”

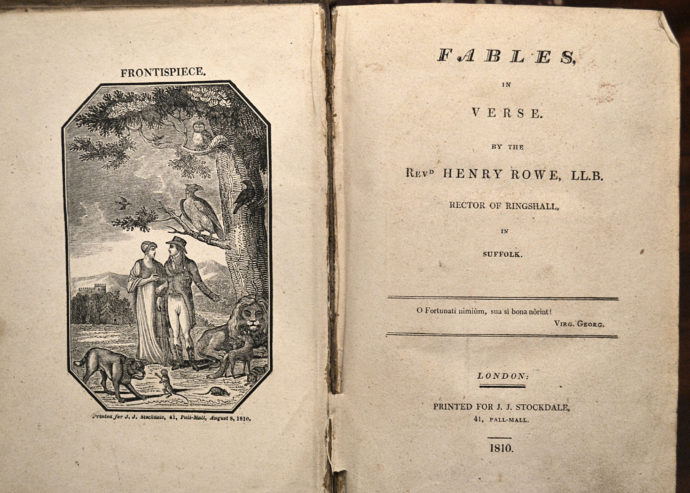

The Rev. Henry Rowe in his preface to Fables in Verse writes: “The origin of conveying Instruction by instructive Fiction, took place, we are well informed, in the earliest ages of the world; being a mode of Education, which, at that period, might be construed the noviciate of life; substituting the study of things, in the place of that of words: which by means, Wisdom and Morality were delivered down to posterity; Wisdom, sublimely forming a collection of that knowledge which Nature had inspired; Morality, in herself, being a refinement on those sentiments which her Divinity had wrought. Nay indeed, the Fabulist not only held rank superior in time of the greatest simplicity, when a mutiny among the rabble was appeased by a Fable; but, born as it were, in the very infancy of science, might be said to have arrived at manhood when learning was at its height, which an admired Classic of the Augustan era alone serves to verify.”

That last phrase, of course, refers to Phaedrus and his verses.

Erich Glas

I know precious little beyond the Wikipedia listing: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erich_Glas

Erich Glas was born in Berlin in 1897 to a Jewish family. According to the Wikipedia listing (which has a caveat “This article needs additional citations for verification.”):

“During the World War I he served as a commando soldier and later as a pilot and an aerial photographer in the Imperial German Army. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich and between 1919 to 1920 at the Bauhaus school in Weimar with Lyonel Feininger and Johannes Itten. He joined “The Young Rheinland”, an artistic group which was founded by Ulrich Leman. After 1926 Glas worked as an independent graphic artist in Weimar and Berlin. In addition, he taught painting and graphics. At that time his work was influenced by Max Liebermann. In 1934 he left Germany because of the Nazi regime and started living in Kibbutz Yagur in Israel, where he changed his first name to Ari.

“His son, Gotthard Glas, better known under the adopted name Uziel Gal was the designer of the Uzi submachine gun.

“Ari Glas died in Haifa in 1973, leaving behind a large selection of his works: paintings, photographs, engravings and prints.”

I’ve not been able to find out whether this “large selection” was left to an institution or stayed with family. His son Uziel Gal, had a son Iddo Gal, who wrote a bio on his father.

I’ve found a Facebook listing for an Iddo Gal and sent him a message. I’ve also contacted two German art dealers: one I’ve worked perviously with in the purchases of art by Gustav Wolf, and two has current eBay listings of non-fable prints by Glas.

Other Fable illustrations

Before Glas’s portfolio came my way, I had obtained four books of fables, bought not for the fables but for the illustrations. The first purchase was in my collecting Dark Ages, i.e the 1970s when I had no direction but bought on a whim. And the place for such uneducated collecting was the Harris Galleries auction house on Howard Street in Baltimore. Barney “Barr” Harris ran several auctions a month from 1952 to 2001, according to a Baltimore Sun obituary. I was a pretty loyal patron through the latter half of the 70s. Oldtimers would nudge me to bid or not to bid many of the times

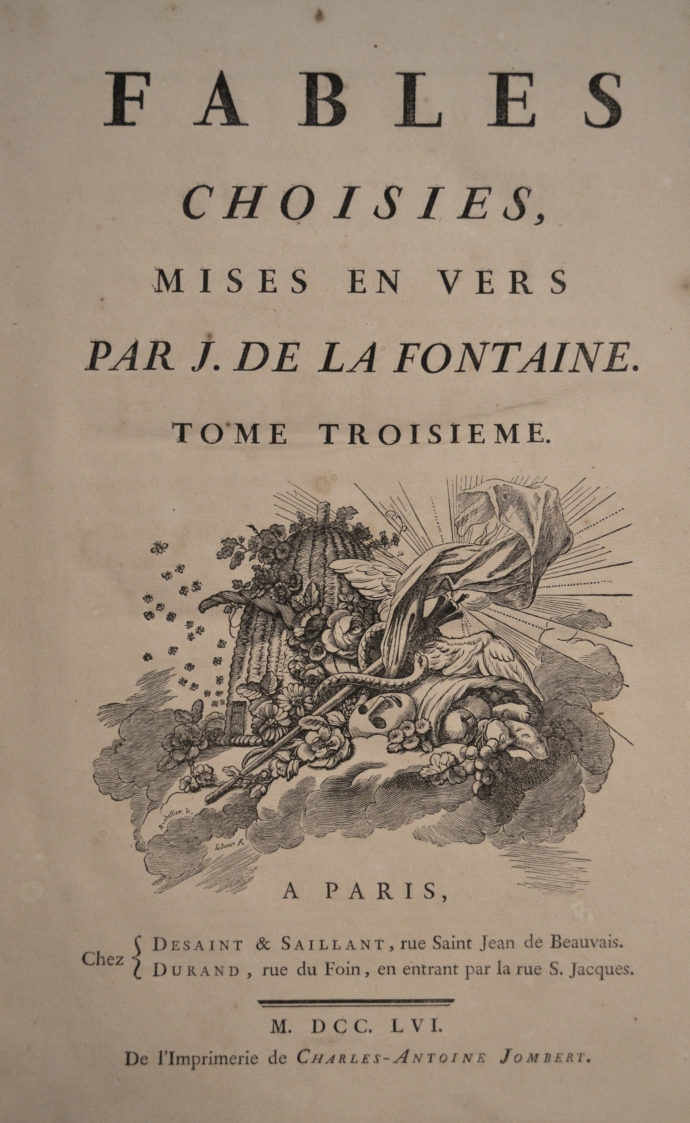

One night I came away with two volumes of the four volumes that comprises the Fables choisies mises en vers of Jean de la Fontaine (Paris: Jombert for Desaint et Saillant, 1755-1759). The covers were taped together, but dozens of wonderful engravings by Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686-1755) were all accounted for.

(These volumes are also notable because of woodcuts, as seen on the title page, designed by J.J. Bachelier and engraved by Jean Michel Papillon. These woodcuts were considered among the best done in France in the 17th century. Or as Herbert Furst in his The Woodcut: An Annual, No. III, (Fleuron Limited, London, 1929) said:

“[Papillon] was, perhaps, not a great artist; but he was a sound craftsman who courageously and even aggressively upheld the standard of a craft which had fallen in his time to a very low estate.”)

The engravings made from Oudry’s designs measured about 11 1/4” x 8 3/8″

These four volumes were se for the engravings made after drawings by Jean Baptiste Oudry (1685–1755).

(By cribbing off of ABEBooks.com listings, I offer this account of how the volumes came to be) “After he became the director of the Beauvais tapestry factory, Oudry began to amuse himself with subjects from La Fontaine’s Fables. He made 276 sketches in all between 1729 and 1735 inspired from La Fontaine’s fables as patterns for Gobelin tapestry.” (That was from one listing. Another said:) “After the financier de Montenault had bought these sketches, he commissioned Charles-Nicolas Cochin the younger (1715–1790) to redraw Oudry’s free drawings for the present edition. Cochin supplied them with precise lines for the engravers. In 1755, when the first volume was finished, financial support by wealthy friends and even by King Louis XV allowed de Montenault to accomplish the work within four years.”

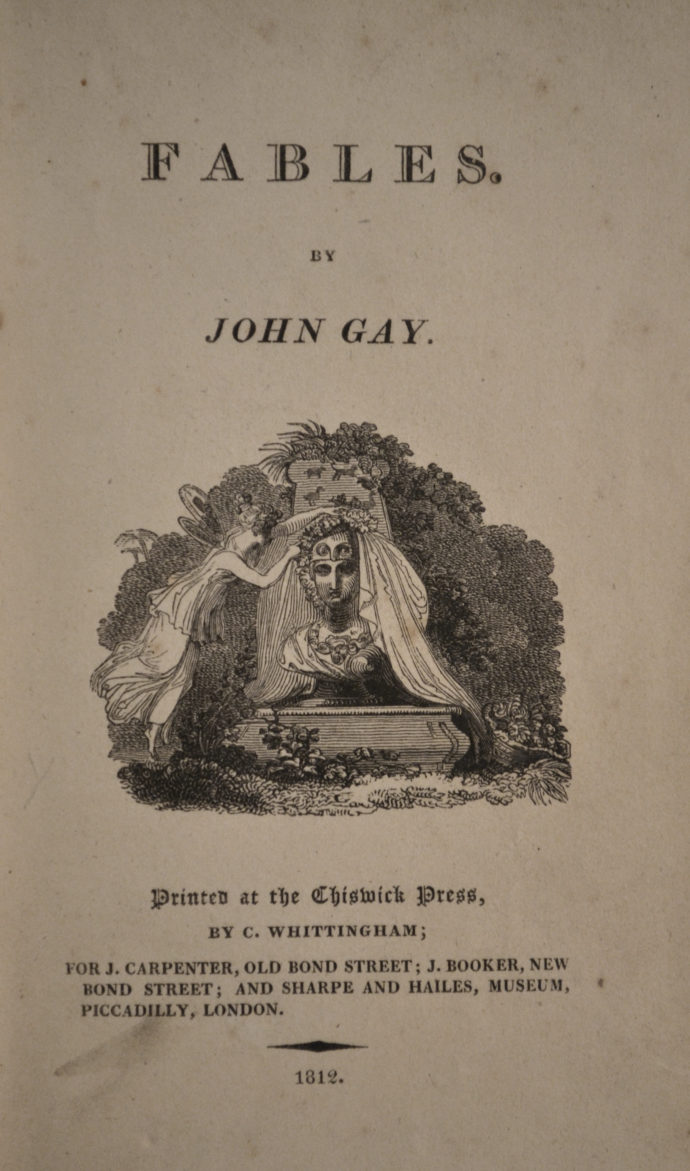

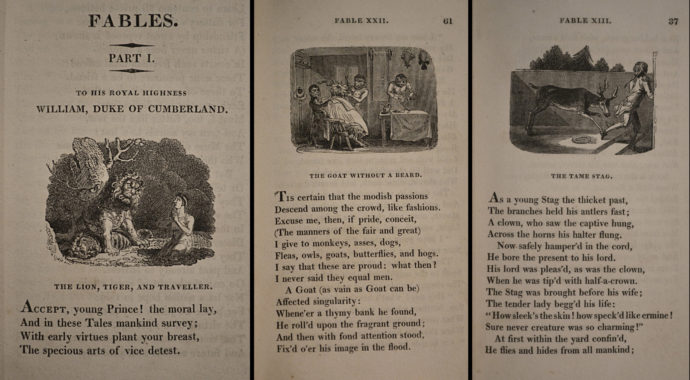

This 1812 volume of Fables by John Gay was also purchased at a Harris Galleries auction. I don’t know when, but I still have auction description sheet. It says it has “engraved title vignette and 88 similarin head- and tail-pieces, engraved by John Thomson, Branstone and Williams.” None of the images are signed, but all strongly owed a debt to Thomas Bewick (1753-1828), whose well-received wood engravings of animals popularized the medium. Bewick also illustrated fables, but I don’t have a copy of that book.

Volumes of fables by John Gay (1685-1732) originally were published during Gay’s lifetime. Also according to a ABEBooks.com listing, “Gay wrote his fables for Prince William, Duke of Cumberland (1721-1765), to whom the first series is dedicated. The dedication is followed by a list of contents, an introduction in the form of a fable, and the 50 fables, all with an engraved illustration. Gay started to write a second series of fables in 1731, a year before his death. The 16 finished fables were posthumously published 7 years later, in 1738.”

A notable late-18th-century edition of his fables (John Stockdale, London, 1793) included 12 etchings by William Blake (1757-1827).

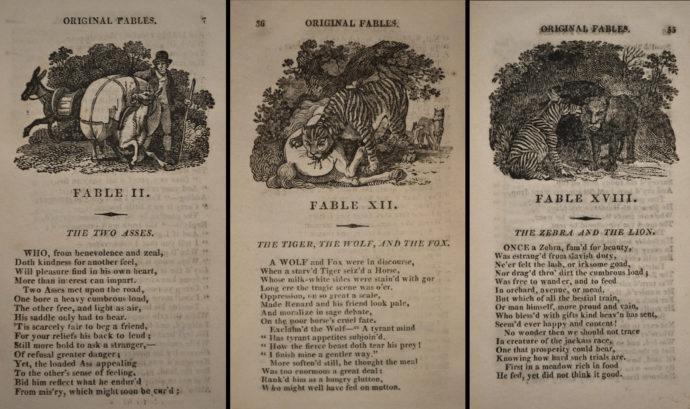

Above are three pages from Fables by John Gay, “Printed at the Chiswick Press,” London, 1812.

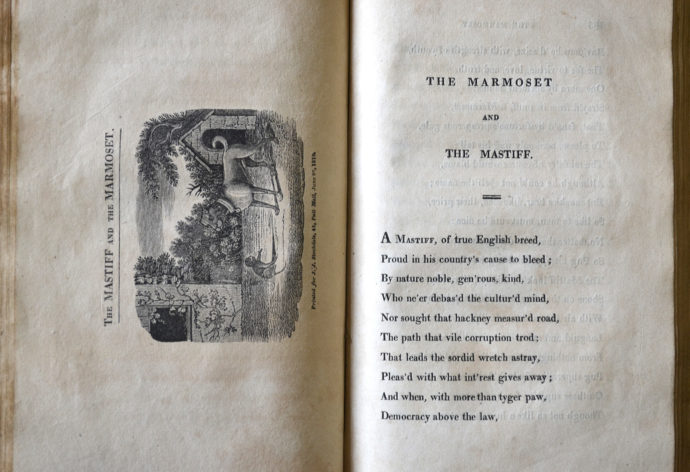

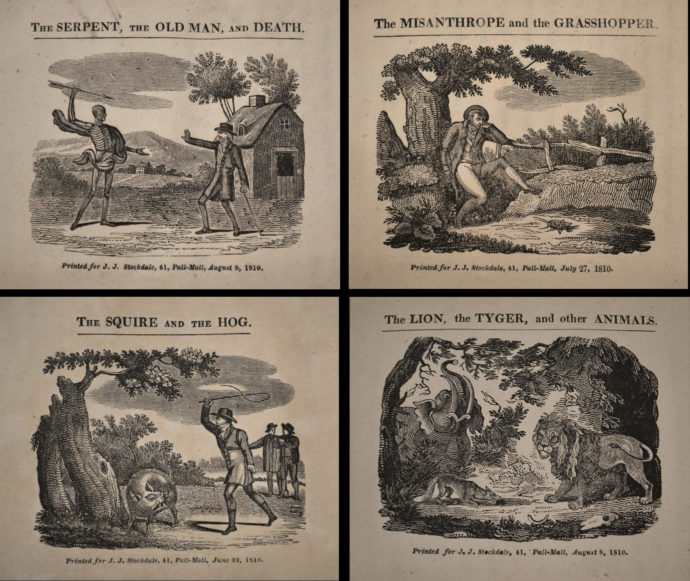

Unlike the 1812 Gay’s Fables, the wood engravings in Fables in Verse by the Rev. Henry Rowe were printed on separate pages opposite the start of each fable. This plus turning the images 90 degrees allowed the images to be larger than if placed atop the verse. For instance the prints in Rowe are about 2 1/2”x 3 3/8” (when turned), while the prints in Gay are about 2” x 1 1/2”. (The Oudry engravings in the Fontaine book are also printed on a separate page.)

Above is a selection of illustrations in the Rev. Rowe’s Fables.

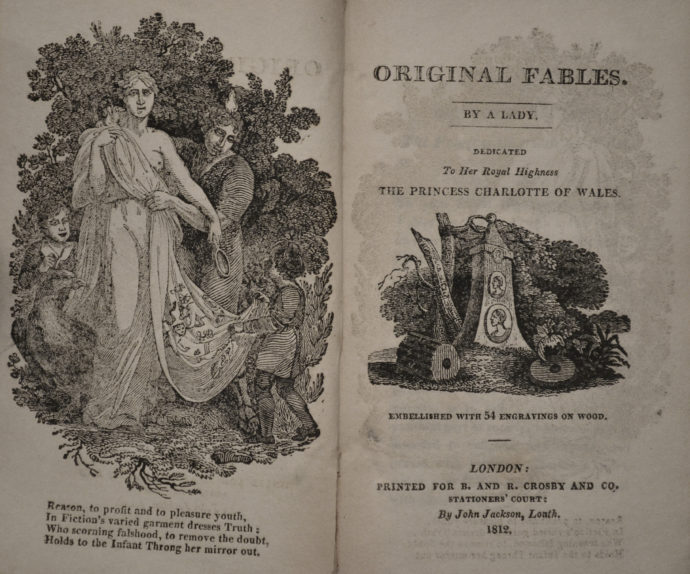

Checking with ABEBooks.com, this seems to be a second edition. There’s a “W. Calvert, Shire Lane, Lincoln, 1810” printed for “for B. Crosby and Co.” In my 1812 edition, “John Jackson, Lonth” did the printing for Crosby and Co. Regardless, I love the poem under the frontispiece:

Reason, to profit and to pleasure youth,

In Fiction’s varied garment dresses Truth:

Who scorning falshood [sic], to remove the doubt,

Holds to the Infant Throng her mirror out.

Above are three pages from Original Fables by a Lady.

The one constant in these books of fables is that the fables are all presented in verse. I didn’t show the text in the Fontaine volumes, but the fables are in verse too.

Erich Glas and Phaedrus

Immediately after I sighted the Glas portfolio on eBay, I checks out ABEBooks.com and found three other numbered complete sets, plus one proof (“probestruke”), plus a set minus two prints, plus one dealer offering the prints separately. That was quite interesting because only 50 sets were made. There’s a rather extraordinary percentage of sets on sale at the same time, nearly 100 years after publication. Was there a common source, an estate offering perhaps?

Immediately after I sighted the Glas portfolio on eBay, I checks out ABEBooks.com and found three other numbered complete sets, plus one proof (“probestruke”), plus a set minus two prints, plus one dealer offering the prints separately. That was quite interesting because only 50 sets were made. There’s a rather extraordinary percentage of sets on sale at the same time, nearly 100 years after publication. Was there a common source, an estate offering perhaps?

While the colophon is undated in my set, all the online sellers list it as 1920. So I checked online for info on the publisher: Amsler & Ruthardt, Berlin. The British Museum website dates the firm from 1860 to 1921 and says: “Print dealers and publishers based in Berlin. Founded in 1860 in Berlin by Hermann Amsler and Theodor Ruthardt; sold in 1877 to the brothers Louis Gerhard Meder (q.v.) and Albert Meder who ran the firm until after 1920.”

On the same search I come up with some etchings by Max Klinger (1857-1920). Oddly enough the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco Museum website offers some Klinger images for Der Fuss, published by Amsler & Ruthardt in 1923.

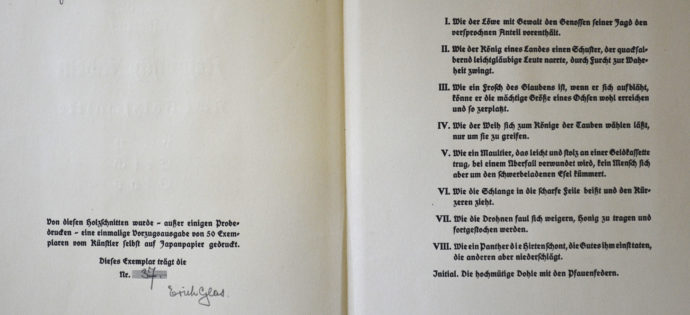

Anyway I have copy No. 37. The only text other than the colophon is a Roman numerated list of sentences in Gothic-font German describing the eight wood engraving and a historiated initial “D.” So I attempt to transcribe the font into a Roman font and then try out an online translation site.

I wasn’t quite happy with the results. So I asked Oliver Shell, Associate Curator of European Painting and Sculpture, to help me out. For instance for the colophon, I got: “Of these woodcuts, a single special edition of 50 copies was printed on Japanese paper by artist himself, with a few testimonials.” But Shell’s effort was noticeably smoother: “Of these woodcuts, with the exception of a few trial prints, a single special edition of 50 copies was printed on Japanese paper by artist himself.”

The colophon and descriptive list of the prints.

Once I got Shell’s translations I was able to sequence the prints. (I numbered lightly in pencil inside each print folder.) But I wanted a more complete sense of what print was about, at least a synopsis of each fable. Once again, an online search brought me to free ebooks at gutenberg.org and “The Fables of Phaedrus, literally translated into English prose with notes” by Thomas Henry Riley and “a metrical translation” by Christopher Smart. The book was published in 1887 by George Bell & Sons, London. In other words for each fable there would be a prose version and a verse version.

This ebook had 91 fables by Phaedrus, plus 31 attributed to him as well as 34 more of unknown authorship. Using Shell’s translation, would I find Erich Glas’s 8 among those 156? I had to scroll from the ebook several times. Sometimes the match-up was obvious; other times not. But I did succeed to finding 8 matches.

Pairing prints with fables

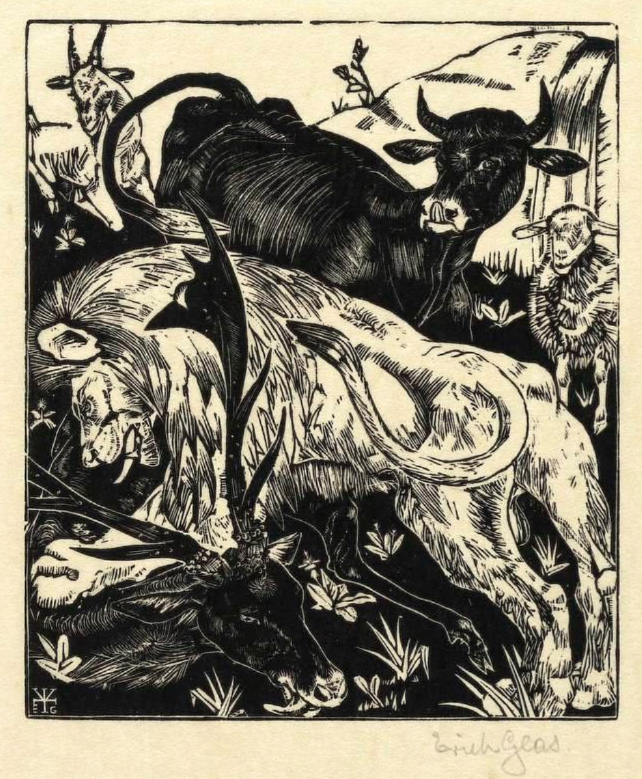

Image: 4 1/4” x 3 5/8″

I present them in the sequence that Gals used: No. I through VIII. Oliver Shell’s translation is in blue. Then I give the book and fable number of the matched Phaedrus fable, followed by the title, the the moral, and finally the prose version of the fable.

(The fable in verse form can be found at gutenberg.org Go to the table of contents; find the fable by seeking the book and fable number as given in the sequence below; then tap on the second number in blue after the fable title.)

I. As the lion uses his might to deny his hunting companions their promised share.

Book I, Fable V.

THE COW, THE SHE-GOAT, THE SHEEP, AND THE LION.

An alliance with the powerful is never to be relied upon: the present Fable testifies the truth of my maxim.

A Cow, a She-Goat, and a Sheep patient under injuries, were partners in the forests with a Lion. When they had captured a Stag of vast bulk, thus spoke the Lion, after it had been divided into shares: “Because my name is Lion, I take the first; the second you will yield to me because I am courageous; then, because I am the strongest, the third will fall to my lot; if anyone touches the fourth, woe betide him

Thus did unscrupulousness seize upon the whole prey for itself.

Image: 4 3/8” x 3 5/8″

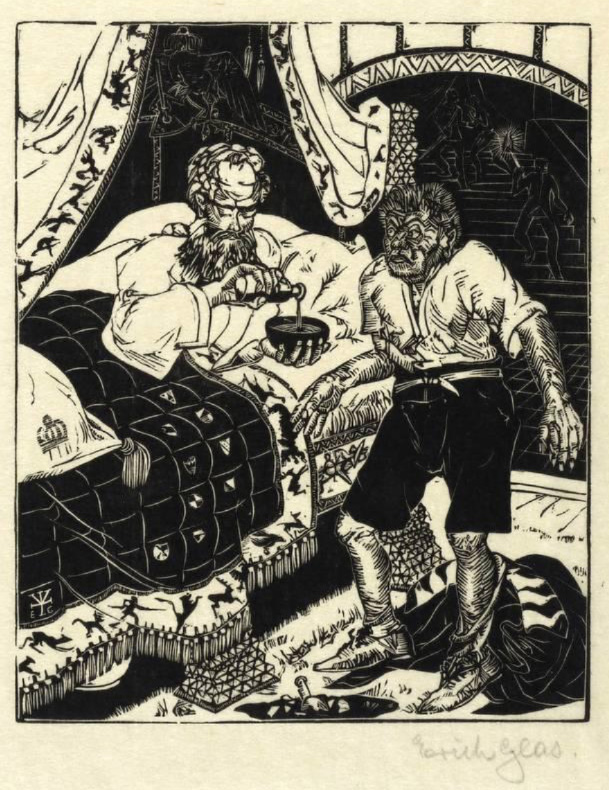

II. As the king of a land uses fear to force a shoemaker who deceives gullible people to tell the truth.

Book I, Fable XIV

THE COBBLER TURNED PHYSICIAN.

A bungling Cobbler, broken down by want, having begun to practise physic in a strange place, and selling his antidote under a feigned name, gained some reputation for himself by his delusive speeches.

Upon this, the King of the city, who lay ill, being afflicted with a severe malady, asked for a cup, for the purpose of trying him; and then pouring water into it, and pretending that he was mixing poison with the fellow’s antidote, ordered him to drink it off, in consideration of a stated reward. Through fear of death, the cobbler then confessed that not by any skill in the medical art, but through the stupidity of the public, he had gained his reputation. The King, having summoned a council, thus remarked: “What think you of the extent of your madness, when you do not hesitate to trust your lives to one to whom no one would trust his feet to be fitted with shoes?”

This, I should say with good reason, is aimed at those through whose folly impudence makes a profit.

Image: 4 3/8” x 3 1/2″

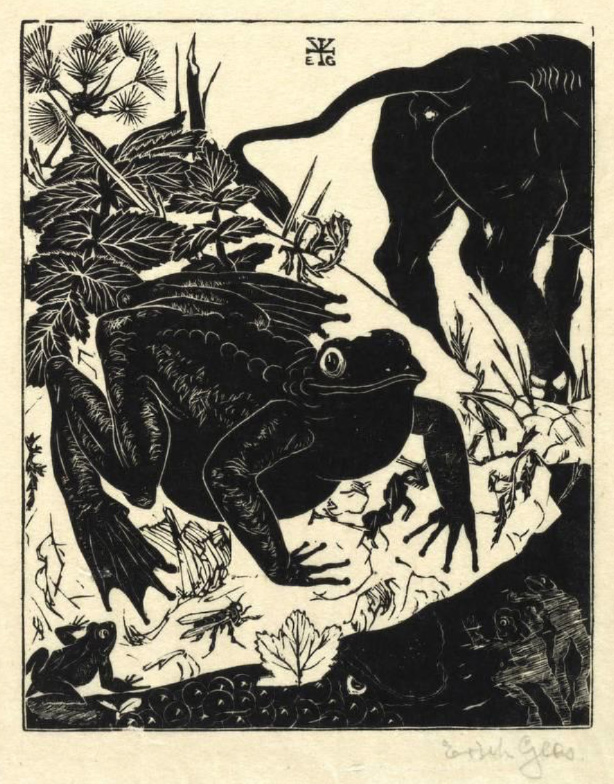

III. As a frog, believing that if he inflates himself he can reach the size of a mighty ox, ends up exploding.

Book I, Fable XXIV

THE FROG AND THE OX.

The needy man, while affecting to imitate the powerful, comes to ruin.

Once on a time, a Frog espied an Ox in a meadow, and moved with envy at his vast bulk, puffed out her wrinkled skin, and then asked her young ones whether she was bigger than the Ox. They said “No.” Again, with still greater efforts, she distended her skin, and in like manner enquired which was the bigger: they said: “The Ox.” At last, while, full of indignation, she tried, with all her might, to puff herself out, she burst her body on the spot.

Image: 4 3/8” x 3 1/2″

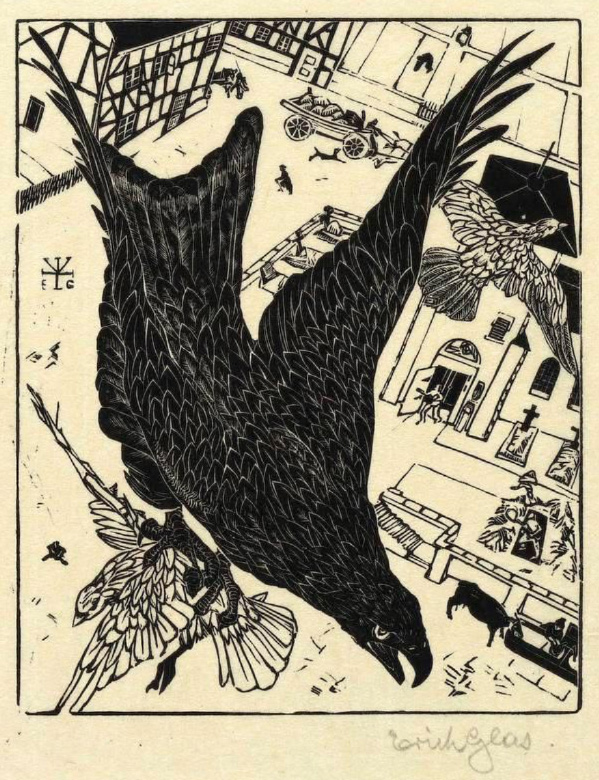

IV. As the hawk has himself elected king of the pigeons just in order to grab them.

Book I, Fable XXXI

THE KITE AND THE PIGEONS.

He who entrusts himself to the protection of a wicked man, while he seeks assistance, meets with destruction.

Some Pigeons, having often escaped from a Kite, and by their swiftness of wing avoided death, the spoiler had recourse to stratagem, and by a crafty device of this nature, deceived the harmless race. “Why do you prefer to live a life of anxiety, rather than conclude a treaty, and make me your king, who can ensure your safety from every injury?” They, putting confidence in him, entrusted themselves to the Kite, who, on obtaining the sovereignty, began to devour them one by one, and to exercise authority with his cruel talons. Then said one of those that were left: “Deservedly are we smitten.”

Image: 4 3/8” x 3 1/2″

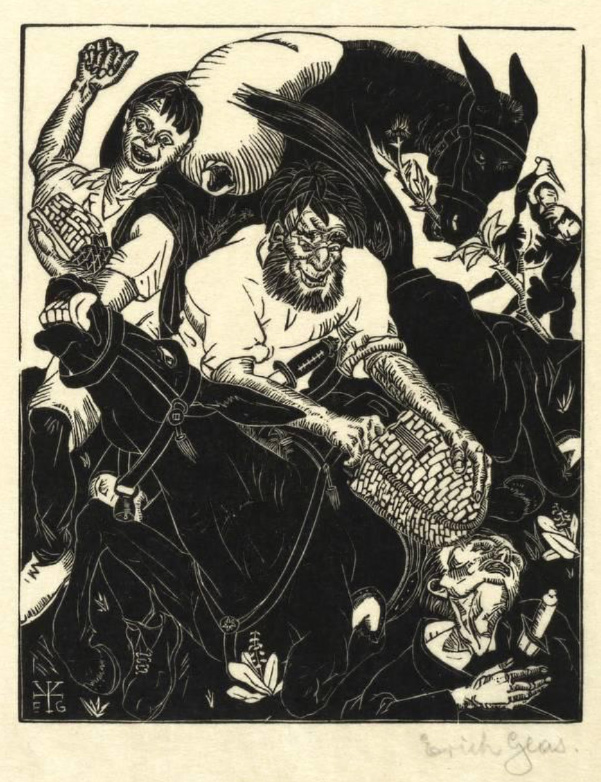

V. As a mule, who lightly and proudly carried a money purse gets wounded in a raid, while nobody cares about the heavily laden ass.

Book II, Fable VII

THE MULES AND THE ROBBERS.

Laden with burdens, two Mules were travelling along; the one was carrying baskets with money, the other sacks distended with store of barley. The former, rich with his burden, goes exulting along, with neck erect, and tossing to-and-fro upon his throat his clear-toned bell: his companion follows, with quiet and easy step. Suddenly some Robbers rush from ambush upon them, and amid the slaughter pierce the Mule with a sword, and carry off the money; the valueless barley they neglect. While, then, the one despoiled was bewailing their mishaps: “For my part,” says the other, “I am glad I was thought so little of; for I have lost nothing, nor have I received hurt by a wound.”

According to the moral of this Fable, poverty is safe; great riches are liable to danger.

Image: 4 3/8” x 3 5/8″

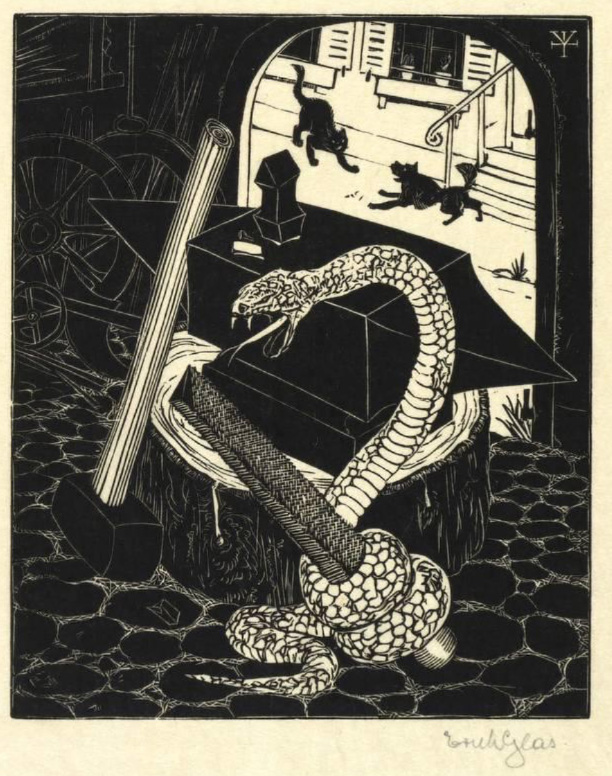

VI. As the snake bites into the sharp file and pulls the shorter one. [

Book IV, Fable VIII

THE VIPER AND THE FILE.

Let him who with greedy teeth attacks one who can bite harder, consider himself described in this Fable.

A Viper came into a smith’s workshop; and while on the search whether there was anything fit to eat, fastened her teeth upon a File. That, however, disdainfully exclaimed “Why, fool, do you try to wound me with your teeth, who am in the habit of gnawing asunder every kind of iron?”

Image: 4 3/8” x 3 1/2″

Andreas Johns, the grandson of Austrian printmaker Emma Bormann, helps make idiomatic sense of the German text “VI. Wie die Schlange in die scharfe Feile beißt und den Kürzeren zieht.” He commented that it “can be translated literally as ‘VI. How the snake bites into the sharp file and pulls the shorter [one].’ The idiom ‘den Kürzeren ziehen’ (‘to pull/draw the shorter [one]’) refers to drawing lots or straws (to make a choice or selection by chance). Pulling the short straw means that you’ve lost, so one possible translation is ‘How the snake bites into the sharp file and comes out a loser.’ ”

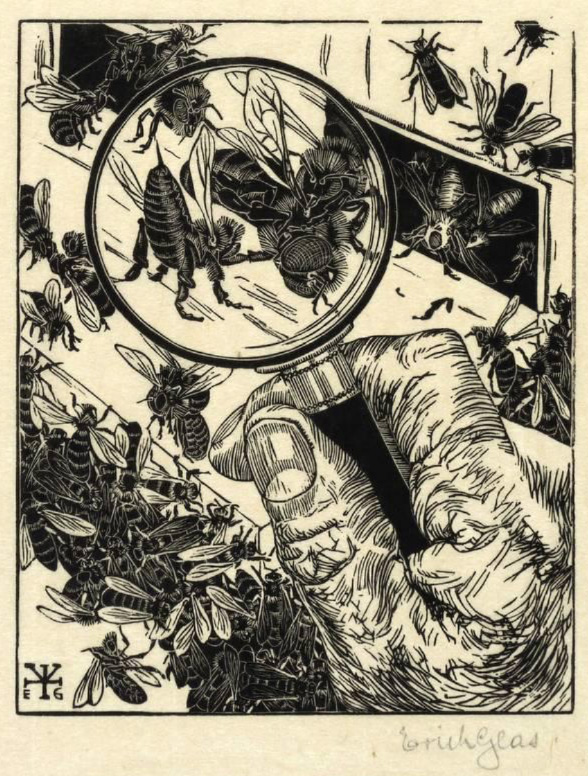

VII. As the drones lazily refuse to carry honey and get bitten till they leave.

Book III: Fable XIII

THE BEES AND THE DRONES, THE WASP SITTING AS JUDGE.

Some Bees had made their combs in a lofty oak. Some lazy Drones asserted that these belonged to them. The cause was brought into court, the Wasp sitting as judge; who, being perfectly acquainted with either race, proposed to the two parties these terms: “Your shape is not unlike, and your colour is similar; so that the affair clearly and fairly becomes a matter of doubt. But that my sacred duty may not be at fault through insufficiency of knowledge, each of you take hives, and pour your productions into the waxen cells; that from the flavour of the honey and the shape of the comb, the maker of them, about which the present dispute exists, may be evident.” The Drones decline; the proposal pleases the Bees. Upon this, the Wasp pronounces sentence to the following effect: “It is evident who cannot, and who did, make them; wherefore, to the Bees I restore the fruits of their labours.”

This Fable I should have passed by in silence, if the Drones had not refused the proposed stipulation.

Image: 4 1/4” x 3 1/2″

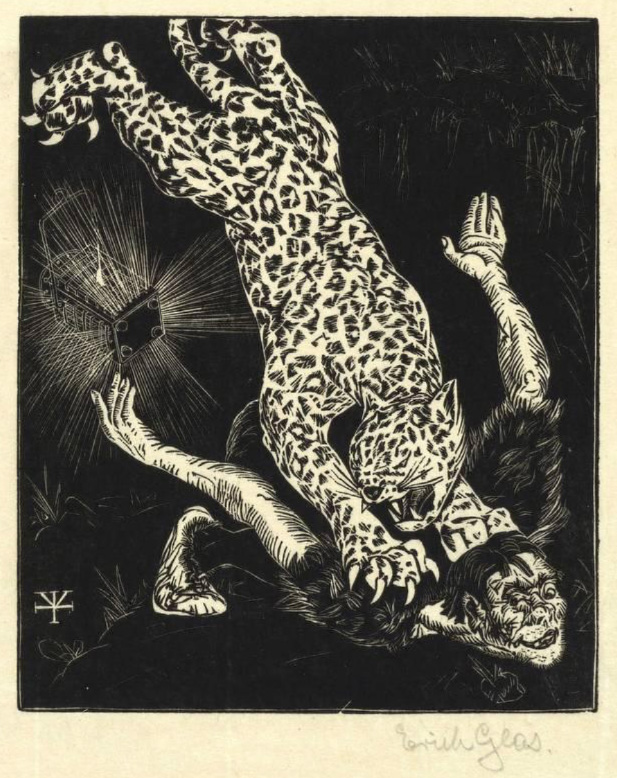

VIII. As a panther spares shepherds who do good to him while striking down the others.

Book III, Fable II

THE PANTHER AND THE SHEPHERD.

Repayment in kind is generally made by those who are despised.

A Panther had once inadvertently fallen into a pit. The rustics saw her; some belaboured her with sticks, others pelted her with stones; while some, on the other hand, moved with compassion, seeing that she must die even though no one should hurt her, threw her some bread to sustain existence. Night comes on apace; homeward they go without concern, making sure of finding her dead on the following day. She, however, after having recruited her failing strength, with a swift bound effected her escape from the pit, and with hurried pace hastened to her den. A few days intervening, she sallies forth, slaughters the flocks, kills the shepherds themselves, and laying waste every side, rages with unbridled fury. Upon this those who had shown mercy to the beast, alarmed for their safety, made no demur to the loss of their flocks, and begged only for their lives. But she thus answered them: “I remember him who attacked me with stones, and him who gave me bread; lay aside your fears; I return as an enemy to those only who injured me.”

Each signed wood engraving was printed on a very delicate Japan paper, which is tipped onto a stiff but thin folder. The original owner has signed the inside of each folder, with the date 1923.

A crow-like bird with three peacock tail feathers sits in front of the letter “D.” This initial comes at the end of Glas’s image list. (Image: 1 1/4” x 1 1/4”)

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/fables-erich-glass-prints-add-to-genre/trackback/

For fable no. 6 about the snake and the file, the German text “VI. Wie die Schlange in die scharfe Feile beißt und den Kürzeren zieht” can be translated literally as “VI. How the snake bites into the sharp file and pulls the shorter [one].” The idiom “den Kürzeren ziehen” (“to pull/draw the shorter [one]”) refers to drawing lots or straws (to make a choice or selection by chance). Pulling the short straw means that you’ve lost, so one possible translation is “How the snake bites into the sharp file and comes out a loser.”

Pingback: Erich Glas: Through the Night vs. Leilot