Erich Glas: Through the Night vs. Leilot/Nights

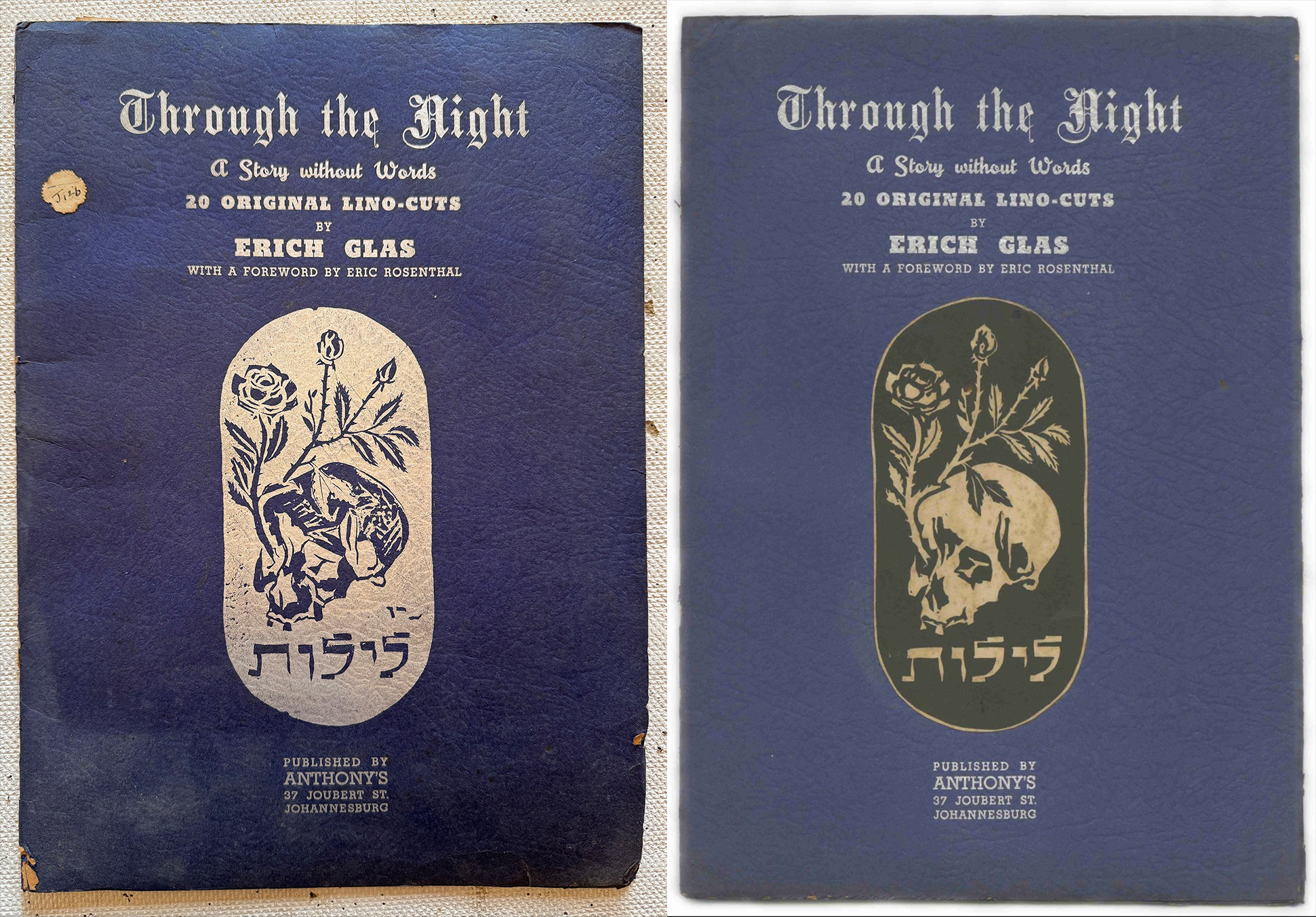

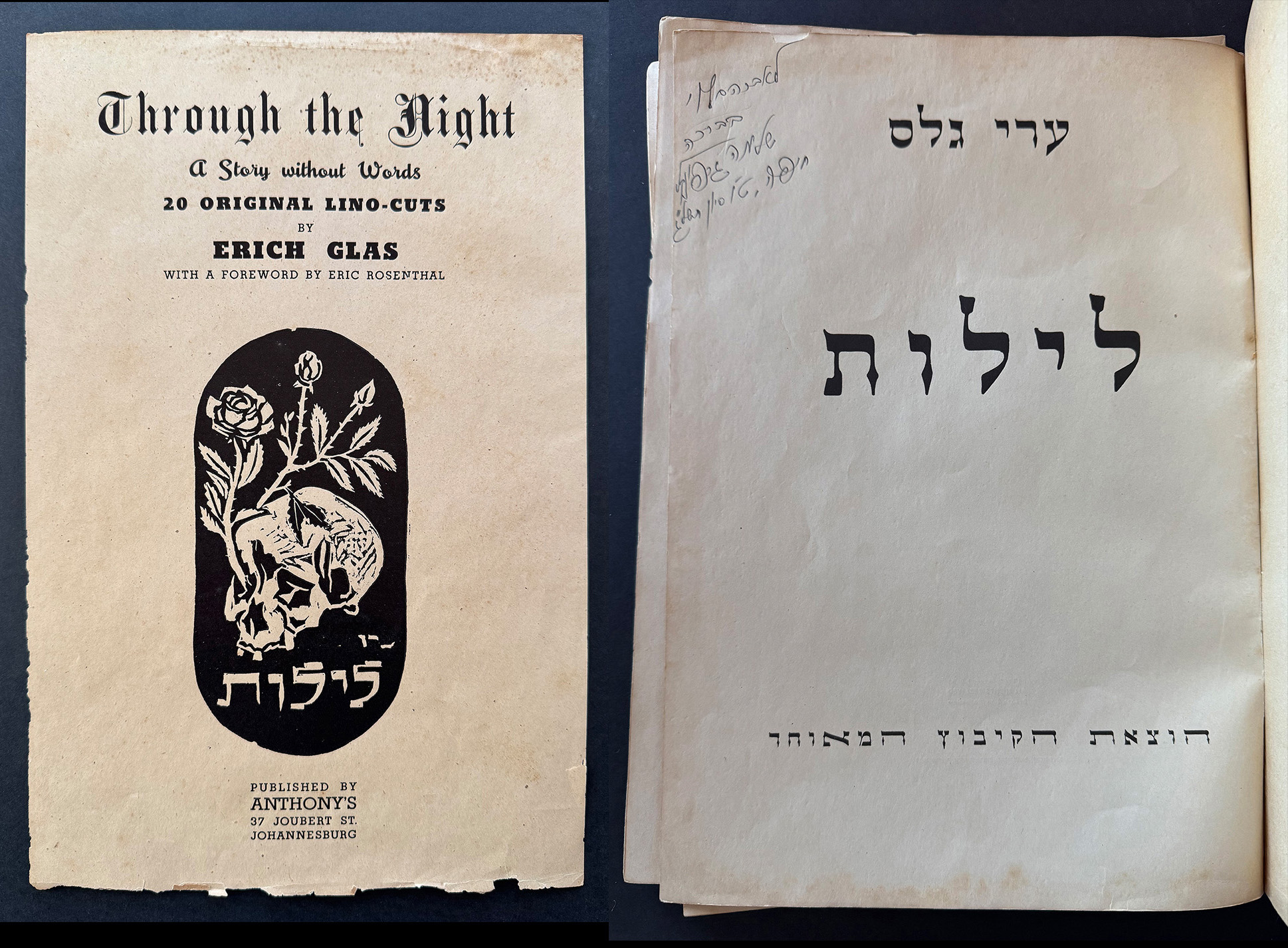

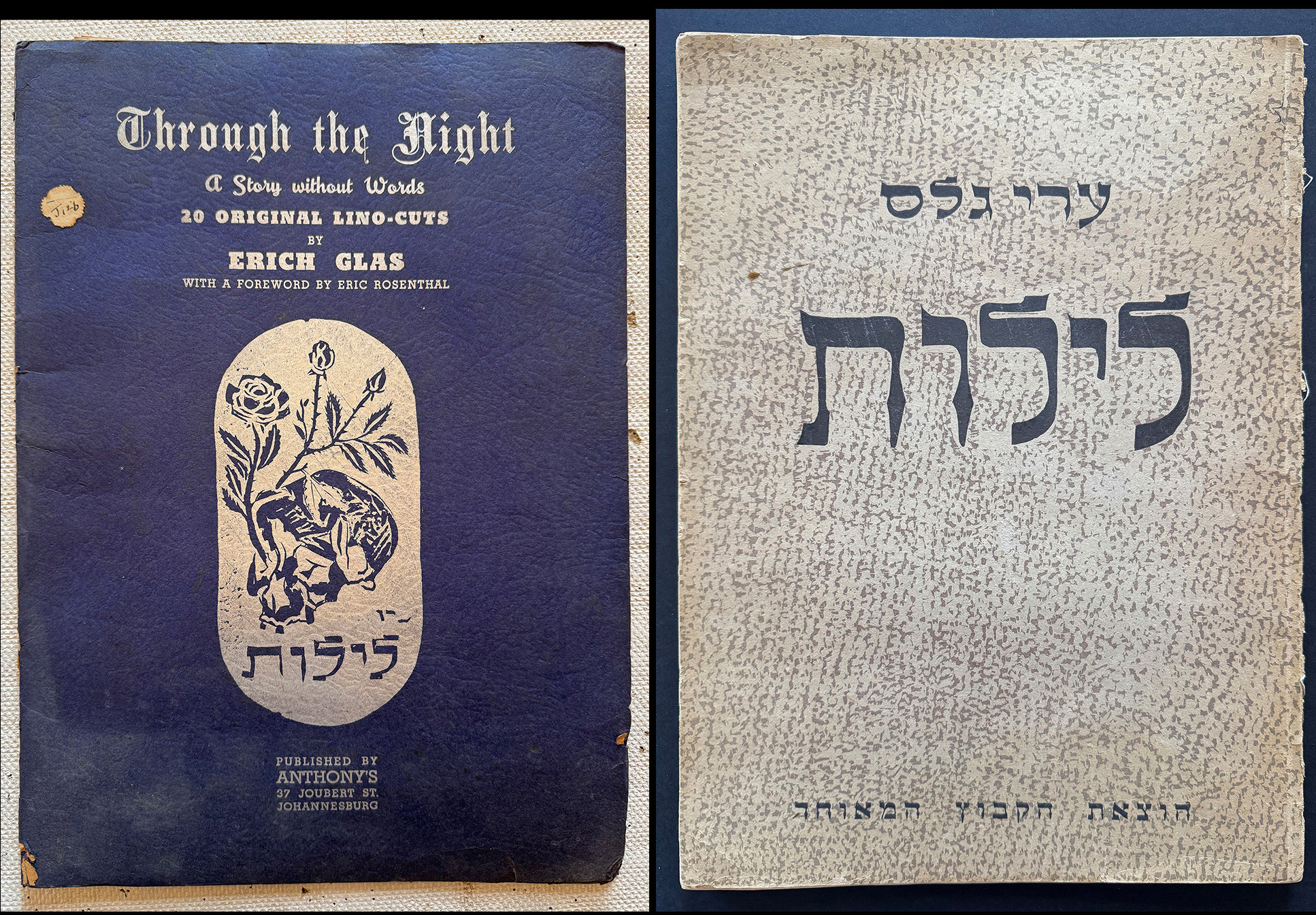

(L) The portfolio cover for “Through the Night” and (R) the cover of the thin “Leilot” book.

(L) The portfolio cover for “Through the Night” and (R) the cover of the thin “Leilot” book.

introduction

The purchase last autumn of the first edition of Erich Glas’s 1943 Holocaust wordless narrative Through the Night provides the opportunity to compare it with the 1945 second edition Leilot (Nights-לילות in Hebrew).

With the invaluable help of two the Glas’s grandchildren Hagar Lev and Iddo Gal, I had made an ART I SEE post on the 1945 edition in October 2018. (LINK) And before that I posted on a c. 1920 portfolio of Glas’s wood engravings Aesopische Fabeln (Aesop’s Fables) in June 2018. (LINK) Lev discovered that initial post on Glas while doing an online reach for her grandfather. She then reached out to me, and, as told in me in my October 2018 post, that contact led me to learn about Leilot.

Glas’s early history is told in depth in my Leilot post. So for here, let me just say: The German-born Glas (1897-1973) escaped to Palästina* in 1934 with his second wife Shoshana (Susi) Adler. There they joined Kibbutz Yagur.

This post will start with how Through the Night/Leilot came about, then discuss the physical differences of the two editions, and only then show what changes Glas made between editions. Not only did he add 10 new linocuts but he also removed two linocuts that appeared in the first edition.

* Hagar Lev prefers using Palästina instead of Palestine on first reference. She said Palästina “is a German term that was used in the first half of the 20th century to refer to the area called ‘Palestine’ by the British regime that had an international mandate over this part of the Middle East.”

All images from the two editions are present courtesy of the Estate of Erich Glas.

The Story of the two editions

In an email for a previous post on Glas, Hagar Lev told the story of how her grandfather came to create Through the Night: “During a few nights in 1942, Erich was lying down sick with high fever. While he was burning with high temperature, he was having horrific visions. Still feverish, he started making sketches, and once he got better, he set out to create the full series.”

In a 2010 video between Israeli artist Yochai Avrahami (YA) and Erich Gal’s third wife, Ziva Glas (ZG), Avrahami asked her about Erich Gal’s Holocaust book and what news did her husband have about Nazi atrocities. She replied: “I’m not sure there was news. Israelis didn’t hear much about it. He said he had some illness. He was isolated for a week or more. In an isolator, yes. When he was there, the idea came to him to make a series of cuts about the atrocities.”

The video conversation continued:

Another woman’s voice: Do you think he was affected by his high fever or….

ZG: Yes, he said so. Like hallucinations.

YA: He shows someone waking from a nightmare and seeing all these images: wailing, getting more and more surreal and intense. He shows a concentration camp.

ZG: A concentration camp, near Weimar.

YA: In Buchewald.

ZG: Yes. I don’t know what she [Maria, Erich Glas’s first wife who remained in Germany] wrote to him. I don’t think she would have written to him. It would’ve been very dangerous. He wanted them [a publishing house in Palestine] to publish it, to distribute it. But they refused. They said, “No, you’re spreading havoc.” They also hid it because a lot of their families stayed there [Germany].

YA: So all these images are imaginary, right?

ZG: Yes.

When I asked Hagar Lev about Glas being unable to find a publisher in Palestine, she said that in 1942 “the reality of what was actually happening in Europe was not clear to all. There were shreds of information, claimed by many to be merely rumors. After all, who could believe such atrocities were real. This was probably the underlying reason for the refusal of Davar, a reputable publication which Erich had worked with from time to time, to publish Leilot in Israel at the time.”

Yet thanks to a relative of Susi Adler’s, the first edition under the name Through the Night was published in South Africa in 1943. According to Lev the connection was through Emilie Adler, Susi’s mother. One of Emilie’s sisters, Fanny Silbermann married Otto Heinrich Dannheister. They lived in South Africa.

In response to my need for specifics on the South Africa connect, Lev wrote in an email last year: “Here’s what I managed to dig up from a 2019 correspondence with Jeremy Dannheisser. Jeremy is what we could call a very distance cousin. He’s the great-grandson of Fanny Sibermann.”

The Dannheisers had three children: Margarete, Robert and Walter. Born in 1909, Walter had two sons: Martin and Peter. Jeremy Dannheisser was a son of Peter’s.

Lev wrote:

Walter Dannheisser owned “Springs Advertiser”–the local newspaper in Springs, a town located approximately 40 kilometers east of Johannesburg.

I asked Jeremy if this could be where the independent publication of Leilot in 1942 started, meaning that through their connections, they connected Erich to “Anthony’s”, the name printed on the Johannesburg publication of the book? Jeremy had no knowledge of this.

★ ★ ★

Hagar Lev with her sister Yael have recently created a website on their great grandparents Karl and Emilie Adler. It details the theft of their art collection by the Nazis and efforts to reclaim some of it. Karl was arrested the day after Pogromnacht, commonly called Kristallnacht. He died at the Dachau concentration camp on Nov. 22, 1938. Emilie managed to escape a few months later and was able to bury her husband’s ashes below Mount Carmel in Palestine.

As to their website efforts, Lev wrote: “I am proud of being able to share the story of Karl and Emilie, brave people, full of love for art, artists, and people at large, whose unconventional taste yielded an extraordinary collection in nature and scope, and whose story ends with a large family in Israel.”

Here’s a link to the website: https://www.karlandemilieadler.com/home

Physical comparison

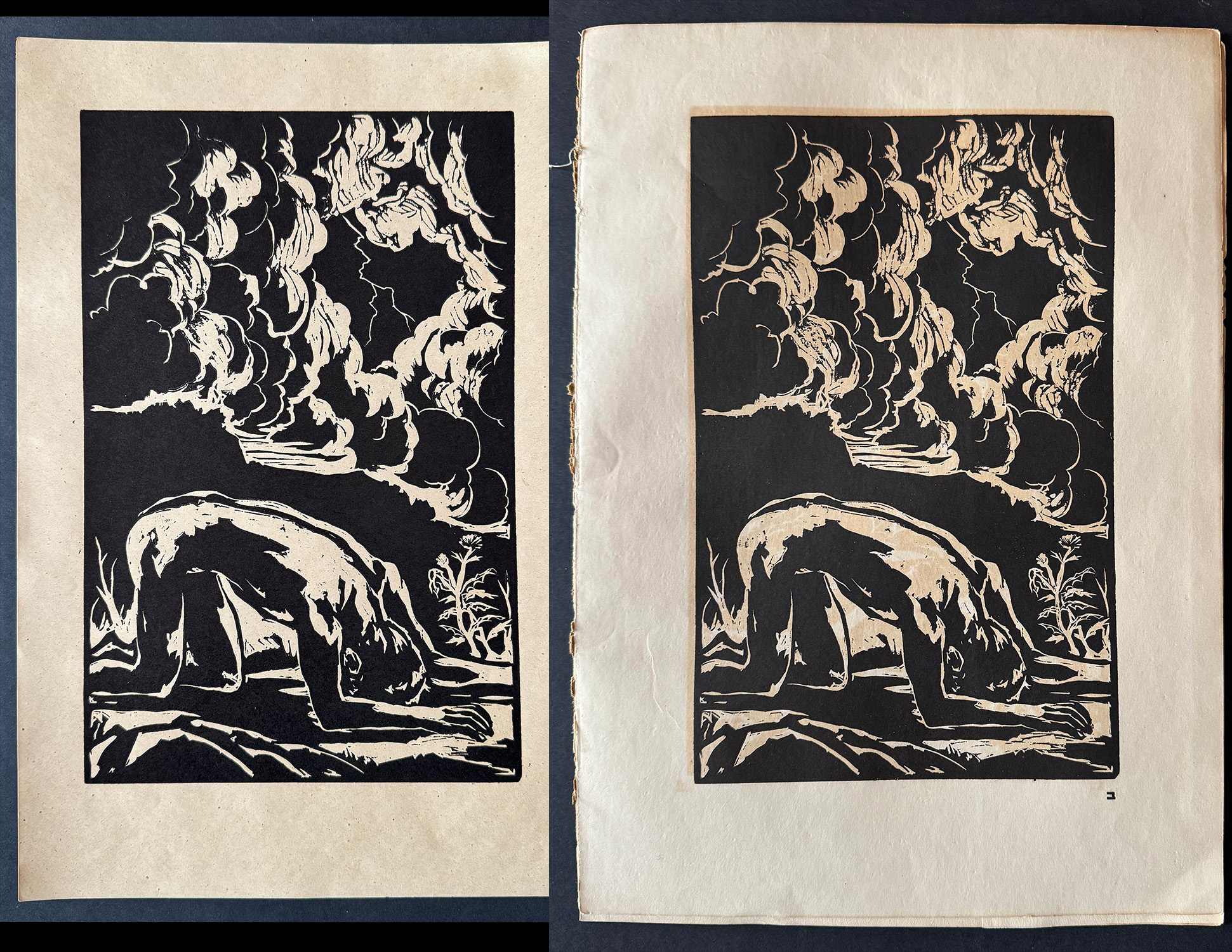

The linocuts on the 1943 edition were printed one to a sheet. The linocuts in the bound 1945 edition were printed on both sides of the sheet. In the above composite are two impressions of the linocuts called “The Storm.” The image on the left is from the 1943 portfolio. The image on the right is from the 1945 book. In that image you can see a “shadow” of the linocut printed on the other side of the sheet. This is particularly notable on the back of the figure.

I haven’t examined each linocut that appears in both editions to see if Glas made any changes to any of the blocks for the second edition. (But no obvious changes have jumped out.) Nor do I know if the linocuts were printed from the blocks in each edition. For instance for the South Africa edition Glas could have had transparent positives made on film and sent there.

If you compare the two, you’ll find areas with less detail in one or the other. For instance on the hip of the figure, there is more detail in the South Africa image. While in the space below the forearm, there is more detail in the Palestine edition.

The Hebrew letter added below the image in the 1945 edition refers to the index. The index in the 1943 edition is numbered, but no numbers appear on the individual sheets.

None the less, the images are of the same size at 9 3/4″ x 6 1/4″ (24.8 x 15.8 cm). The paper in the 1943 edition measures 12 1/2″ x 8″ (31.7 x 20.3 cm). The pages in the 1945 book measure 13 1/8″ x 9 1/2″ (33.3 x 24 cm). And maybe you can even sense from the photographs: The browner, more acidified paper in the 1943 edition is rather brittle, while the paper used in the 1945 edition remains pliant and brighter.

Variations in the 1st edition

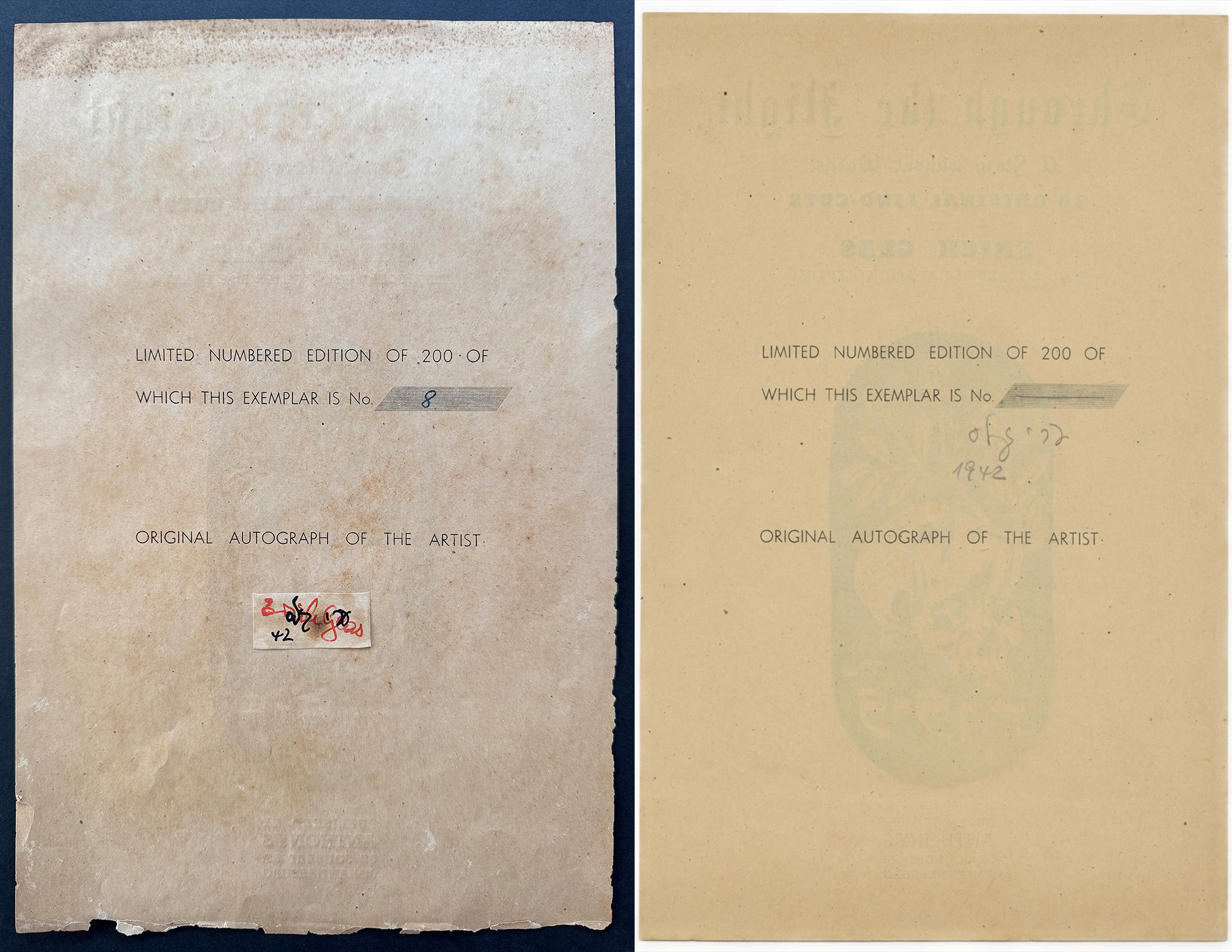

I’ve observed variations in the South Arica edition. While entire edition of 200 might well have been printed in South Africa, Through the Night may have changed according to where it was sold.

My copy of Through the Night is on the left. According to Dana from Tre Zouze, the auction house in Israel from which it was purchased: “We know that this item indeed came from a South-African collection.” On the right is the cover of Through the Night that was sold at auction in 2021. It appears that Glas printed more copies of the linocut cartouche and pasted on top of the one printed in white in South Africa. By printing with black ink on light-colored paper, Glas reversed the light and dark, in short turning the negative image of the cartouche into a positive.

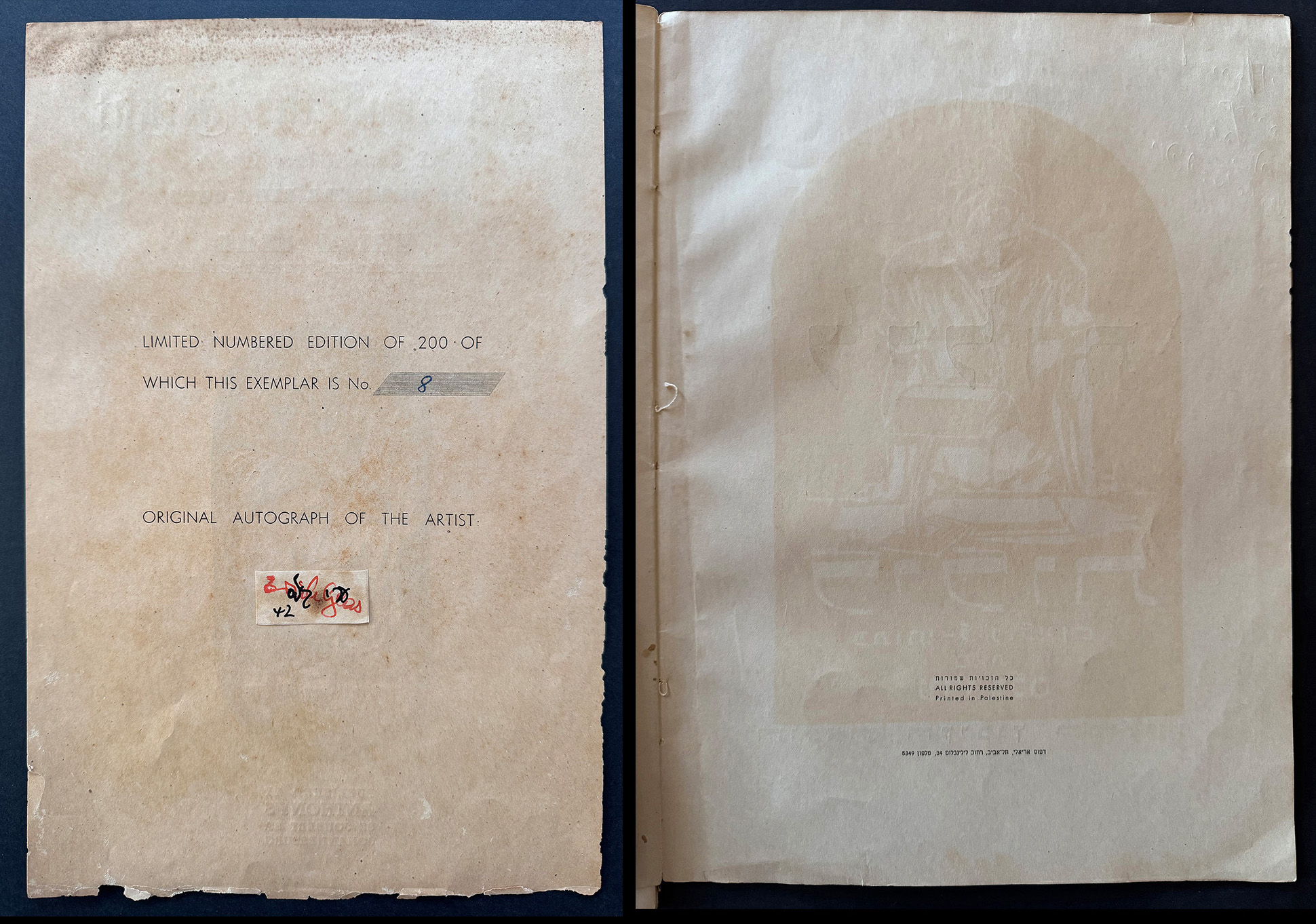

On my copy that came from a South Africa collection Glas’s signature was pasted (left) onto the colophon page. He evidently sent to Anthony’s, the publisher, a certain number of signatures to be pasted onto the colophon page for copies of the portfolio to be sold in South Africa. Note that Glas signed “Erich Glas” in red and he signed “Eri Glas” in Hebrew plus the date in black. But (right) is the colophon from the copy with the cartouche pasted onto the portfolio cover. Here Glas only signed with Hebrew script and the date. Also, according to the 2021 auction listing, Glas signed each of the linocuts. Maybe this was the case for all copies of Through the Night that arrived in Palestine. None of the linocuts in my copy from a South Africa collection are signed.

These are the only copies of Through the Night that I have to compare. But they may well represent two variations of the first edition.

1st vs. 2nd edition

For this section I’d like to introduce an essay to be published this summer by Dr. Rachel E. Perry, Hadassha-Brandeis Scholar in Residence, Weiss-Livnat Holocaust Studies Program, University of Haifa. Her article “ ‘Telepathos’ (Feeling from Afar) in Graphic Albums Created During the Holocaust in the Yishuv” is being published by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and the Oxford University Press journal Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

(Yishuv is the Jewish community in Palestine before independence.)

Her article focuses on Through the Night and and Lea Grundig’s In the Valley of Slaughter, Drawings by Leah Grundig, which was first published in Tel Aviv in early 1944. Perry wrote: “Created far from the sites of extermination, Glas and Grundig’s albums are examples of their authors’ ‘telepathos.’ Derived from the Ancient Greek τῆλε (têle), meaning distant, and πάθος (páthos), meaning feeling (but also perception, passion, experience and, notably, affliction or suffering), telepathos is literally feeling from afar.”

Perry has given me permission to quote from her article during this section on the differences between the two editions. (When you see Perry: what follows is from her essay. She uses Nights when referring to Leilot)

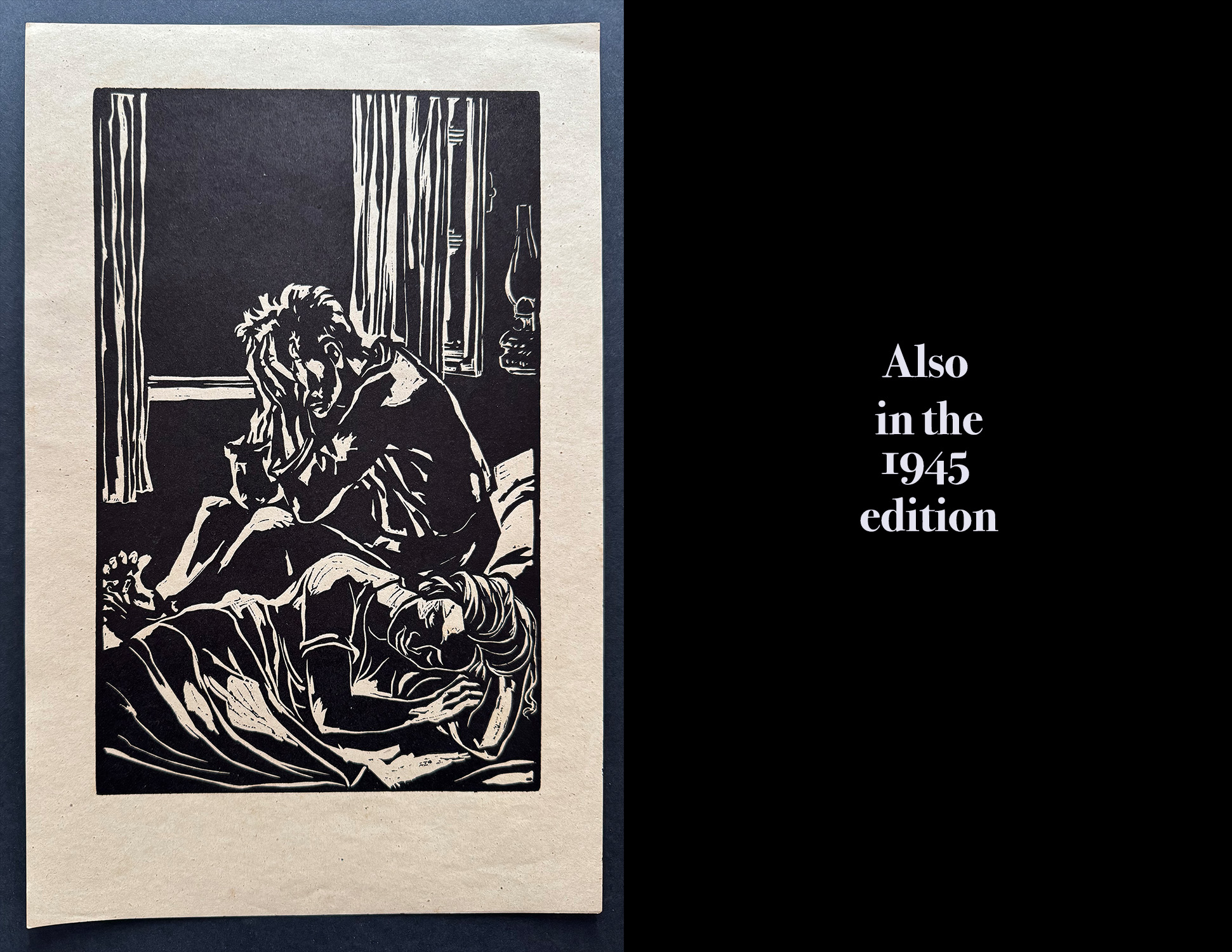

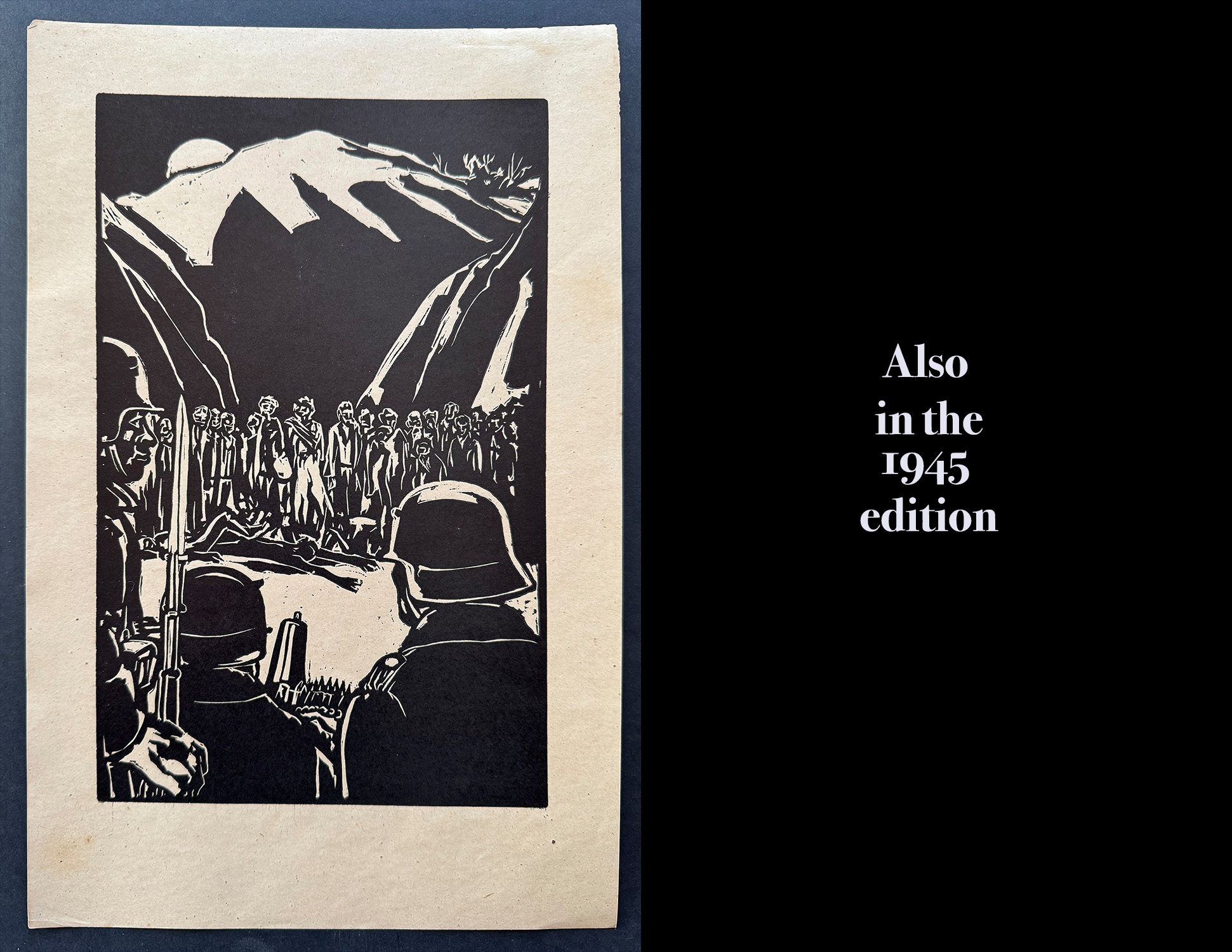

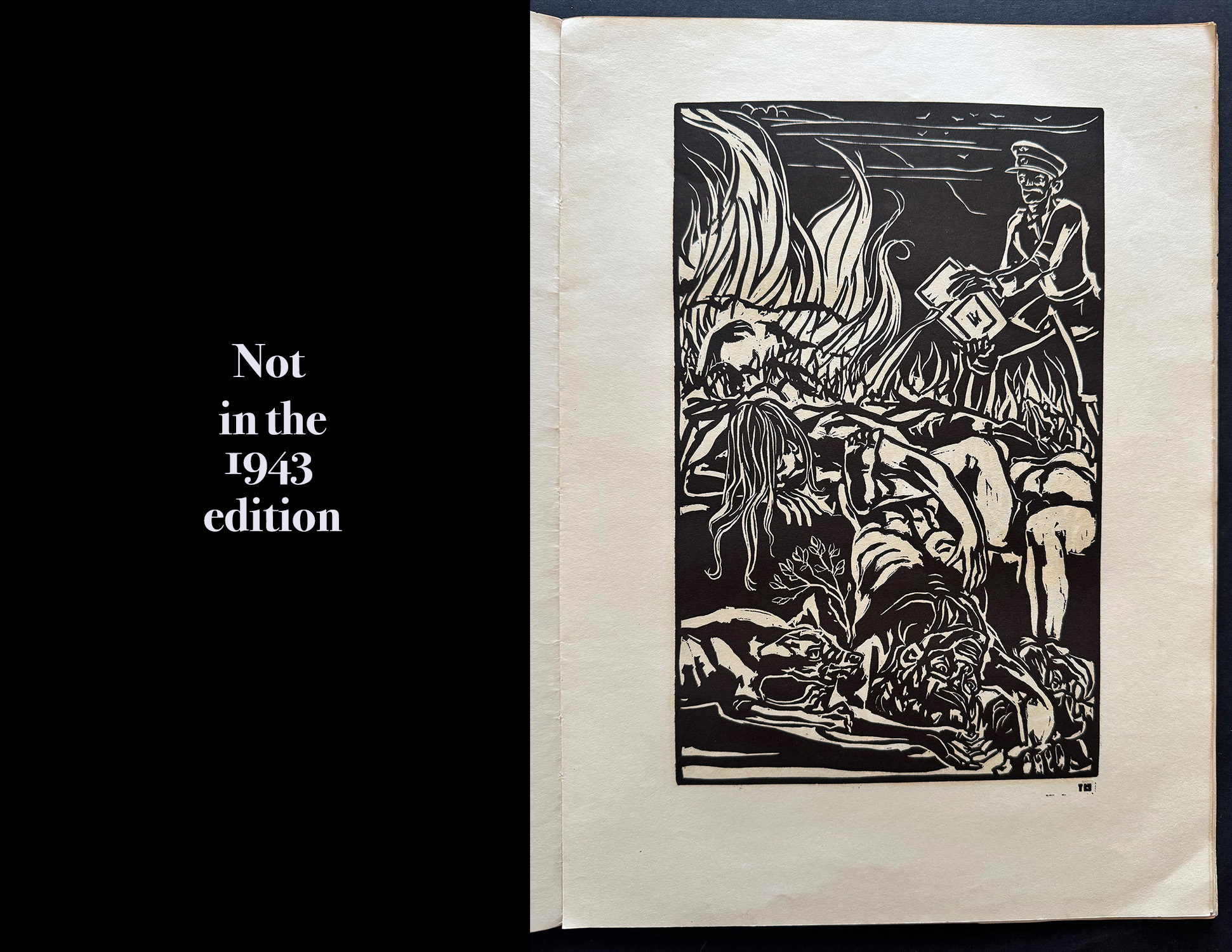

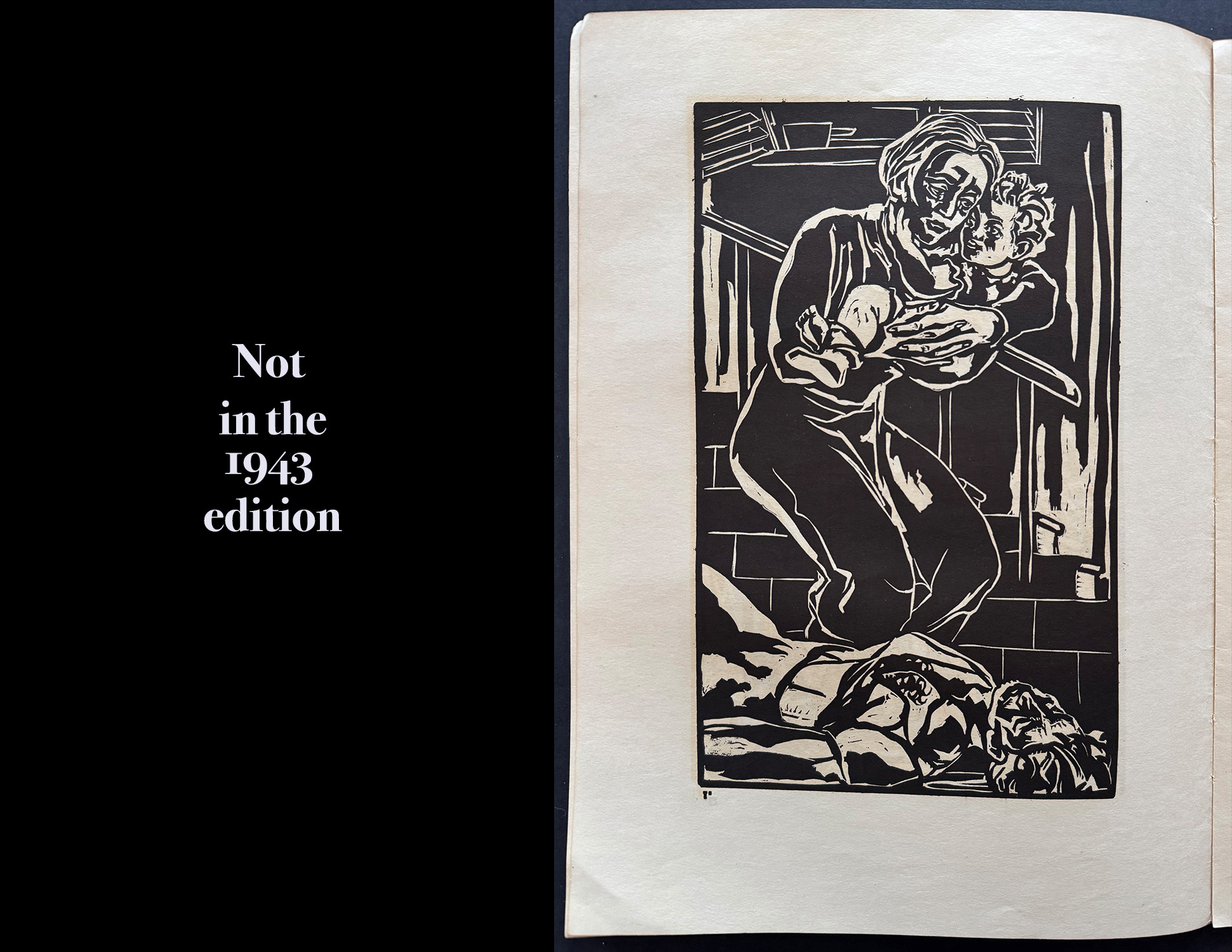

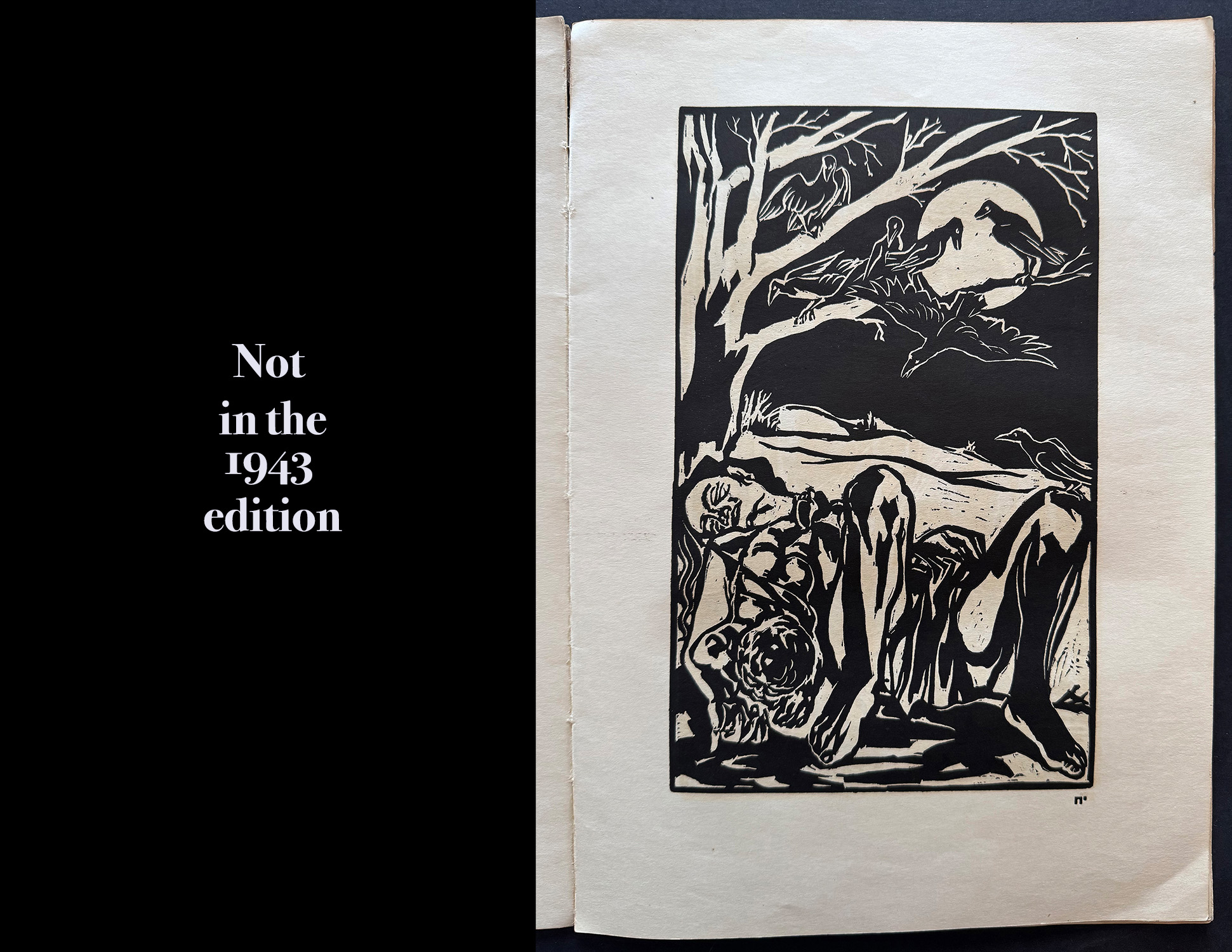

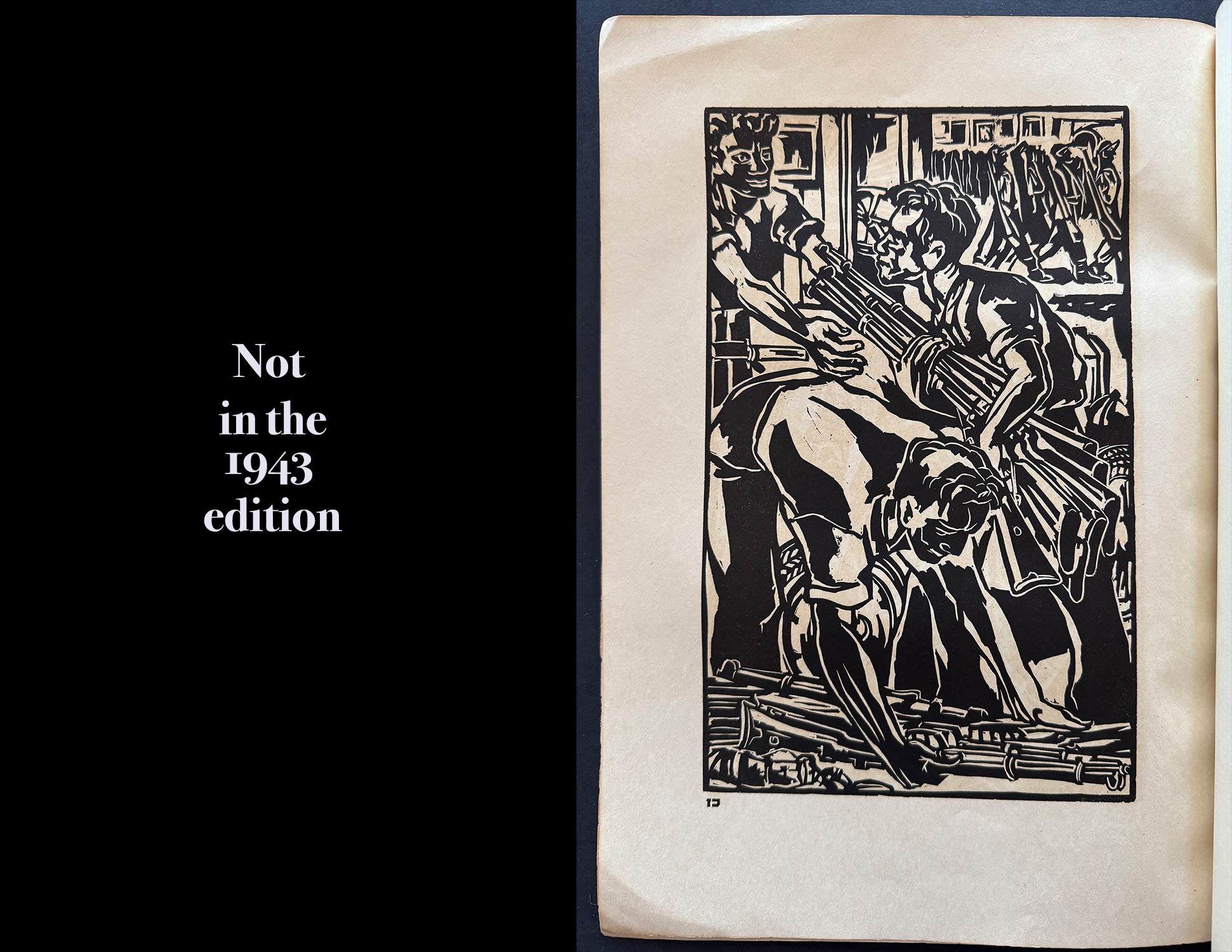

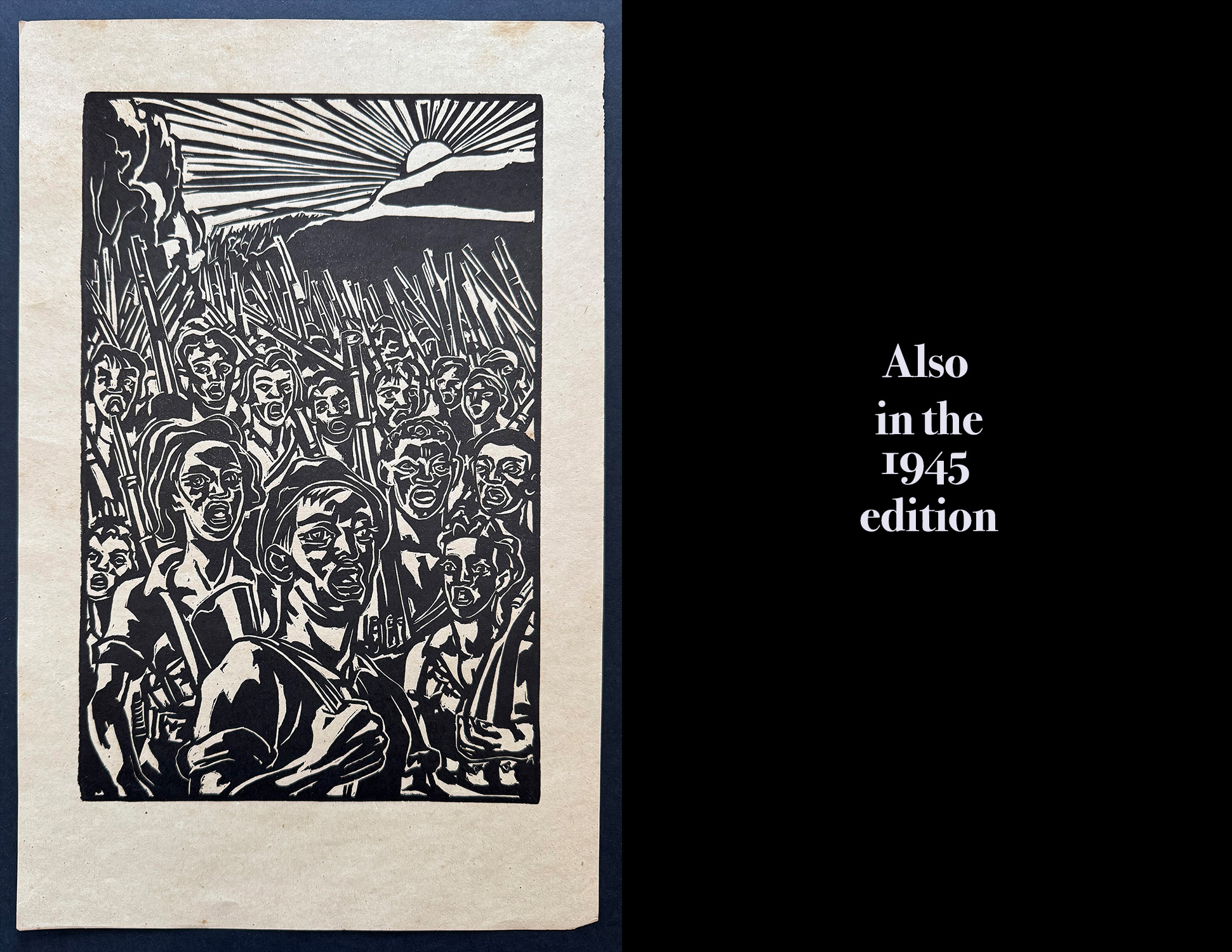

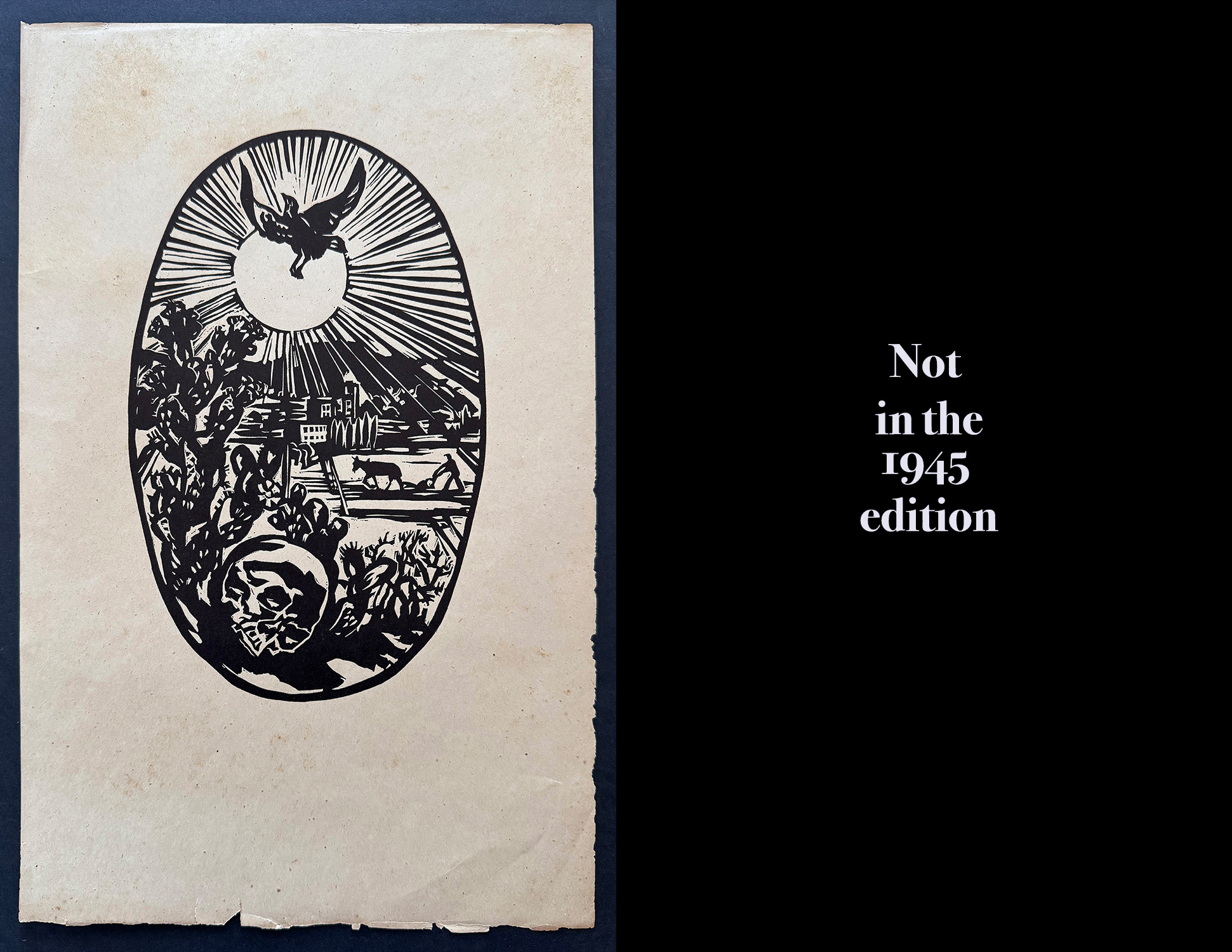

In each of there following pairs, the left half will be from the 1943 first edition of Through the Night; the right half will be from Leilot of 1945. If both editions share the same linocut, the right half will read “Also in the 1945 edition.” If a linocut appears on the right side, it was a linocut added to the 1945 edition and the left side will read “Not in the 1943 edition.” If an image appears on the left and that image was dropped from the 1945 edition, the right side will read: “Not in the 1945 edition.”

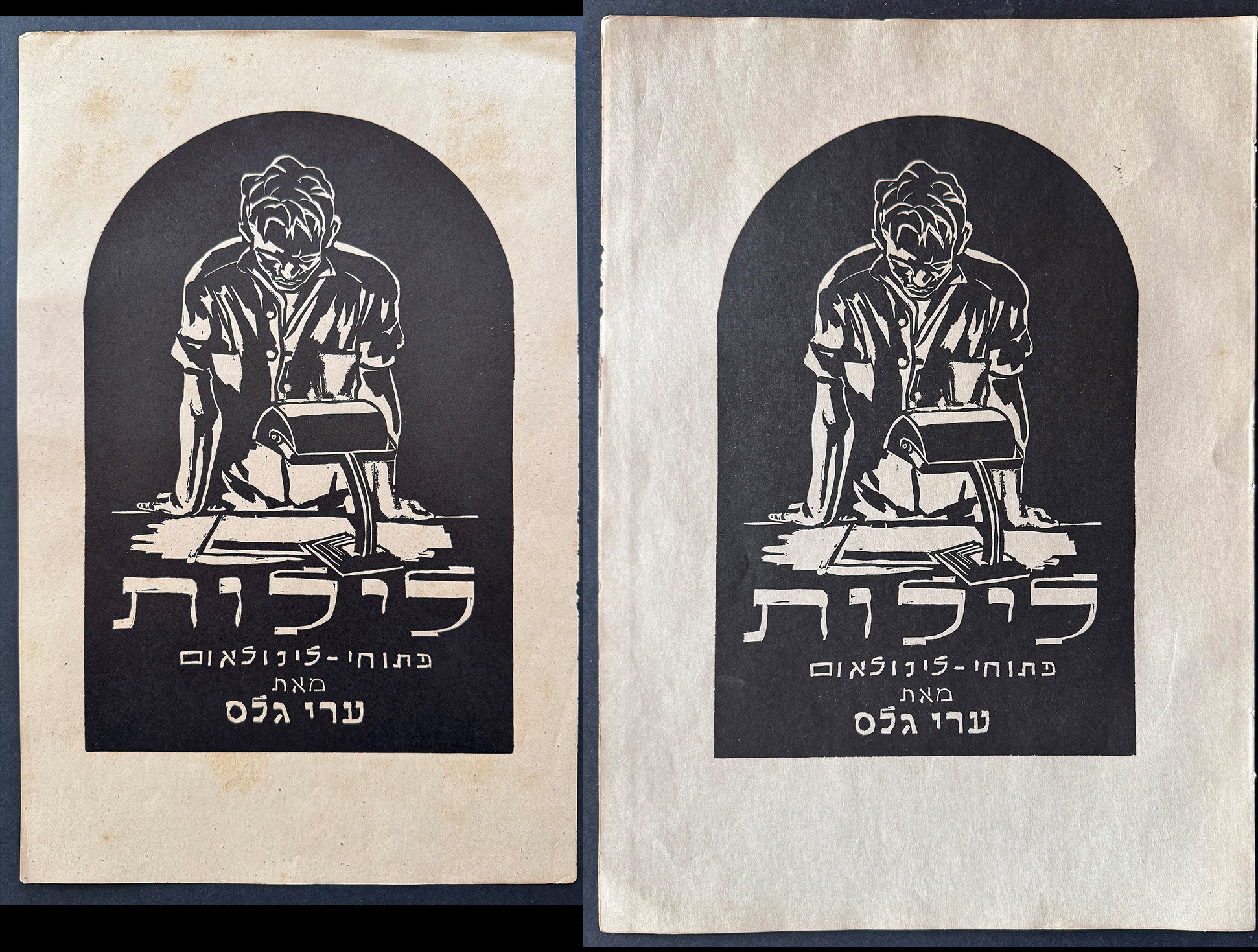

The 1943 portfolio cover (left) as issued in South Africa has white ink on a blue paper. Even Glas’s cartouche of a rose growing out of an eye socket of a skull was printed in white. Glas cut the Hebrew word Leilot into the cartouche. On the color of the string-bound 1945 edition (see two loops of string on the spine on right) Eri Glas’s name in Hebrew floats above the word Leilot. The three words below read: Hotza’at (publishing) Hakibbutz Hameuchad (union of kibbutzim)

Despite the English title Through the Night in the SA edition, in the cartouche Glas cut the Hebrew word Leilot or Nights, just like the title in the 1945 edition.

Rachel Perry wrote in her article: “For the cover illustration, he featured a single skull, with flowers sprouting from one of the eye sockets, suggesting a passage through the ‘night,’ through death to regeneration.” As to the change “Night” became “Nights,” Perry said that Glas “changed the title to the plural Nights, thus moving the work from the story of a single night into an allegory of the Holocaust as an endless series of nights.” But since Glas used Nights in the cartouche, maybe the Night in Through the Night was a mistake.

There is no text on the inside of the portfolio of the 1943 edition nor on the inside of the cover of the 1945 edition.

The title pages repeat the portfolio covers of the 1943 edition and book cover of the 1945 edition. Note that the cartouche is a positive, like the one that Glas pasted onto the copy that was sent to him in Palestine.

The colophon was printed on the reverse of the title page in the 1943 edition. Publisher’s information is on the reverse of the title page of the 1945 edition. Note the offsetting of the next page’s linocut onto this page.

Both editions share a full-page linocut version of the title page. Between the word Leilot and Glas’s name are the Hebrew words for: “linoleum cuts by”

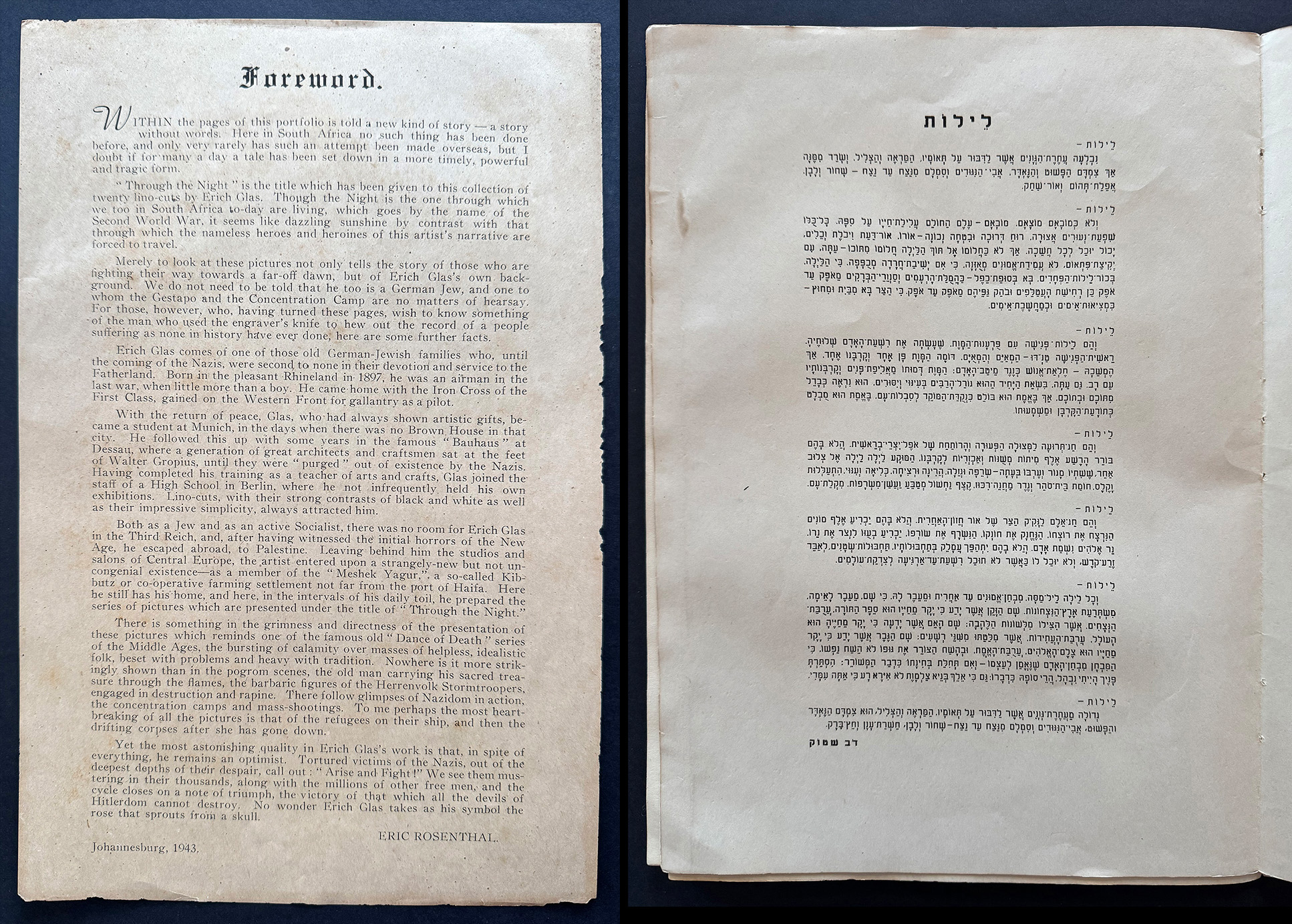

Historian Eric Rosenthal (Wikipedia LINK) wrote the foreword in the 1943 edition. Dov Sadan, the editor of Davar’s literary supplement, wrote the forward in the 1945 edition.

Rosenthal wrote: “There is something in the grimness and directness of the presentation of these pictures which reminds one of the famous old ‘Dance of Death’ series of the Middle Ages, the bursting of calamity over masses of helpless, idealistic folk, beset with problems and heady with tradition…. There follow glimpses of Nazidom in action, the concentration camps and mass shootings. To me perhaps the most heartbreaking of all the pictures is that of the refugees on their ship, and then the drifting corpses after she has gone down.

“Yet the most astonishing quality in Erich Glas’s work is that, in spite of everything, he remains an optimist. Tortured victims of the Nazis, out of the deepest depth of their despair, call out: ‘Arise and Fight!’ … No wonder Erich Glas takes as his symbol the rose that sprouts from the skull.”

That skull and the rose went missing in the later edition.

After noting that Rosenthal used words like “grimness and directness” and “heartbreaking” to describe his response to the linocut, Perry said: “So too, when Glas exhibited Through the Night to members of his kibbutz, at the entrance to the dining hall, it roused strong, emotional reactions. When it was exhibited at the Pevsner House in 1944, one critic wrote that ‘you would think him completely preoccupied with the phenomenon of death.’ ”

When I initially asked Iddo Gal to give me a sense of Dov Sadan’s forward in the 1945 edition, he wrote back: “This is very high Hebrew, poetic and wonderful but with many obscure idioms (think of it like Shakespearean English, with a twist), so one has to read and re-read to make sense.”

Then Gal offered “my take at translating some of the sentences in Dov Sadan’s compelling, lyrical introduction, hoping to convey (via my own private lens) a few of the ideas, and feelings and images, that his words evoke…. Note, the three dots before and after each piece of text aim to remind that this is not a complete translation, just a sample.

Nights – … the range of colors has been absorbed, and what has survived is the eternal contrast, black and white – the darkness of the abyss, and the light of the heavens….

Nights – …they start as an encounter with the calamity of death and his victim. And then follows the worst of humanity against the best of man….

Nights – … every night is a test to the end and beyond, because there, beyond the terror, lies the land of victory….

Nights – …as the tormentor bends his body, his soul remains resolute, and although he is tested, the end follows the poet’s words: though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil….

On the reverse of the forward is the index in the 1943 edition (left). The cartouche was called “Cover Design” and their numbering started after the “Title Page Design.” The numbers were not printed on the pages with the linocuts. In the 1945 edition (right) the index was on a narrow foldout pasted onto the reverse of the forward. It used the Hebrew alphabet for the ordering. The corresponding letter was printed below the image of each linocut.

Evening, called “The Awakening” in Hebrew edition

For linocuts in the 1943 edition I use the linocut’s title that was used in that edition.

“Nights presents as a story within a story;” Perry wrote, “the story of the Holocaust is framed by and nested within the story of how and why the work comes into being. Inserting himself metanarratively, Glas calls attention to his own labor and foregrounds the difficulty of telling–showing this story, reminding his viewer that the album, and the events it relays, is not an imaginary ‘story’ made up, but a made thing and a thing made under pressure….

“Crafted as an autobiographical text, Nights opens in the ‘Evening’ with the artist sitting up in bed, having either awoken from a nightmare or struggling to fall to sleep.”

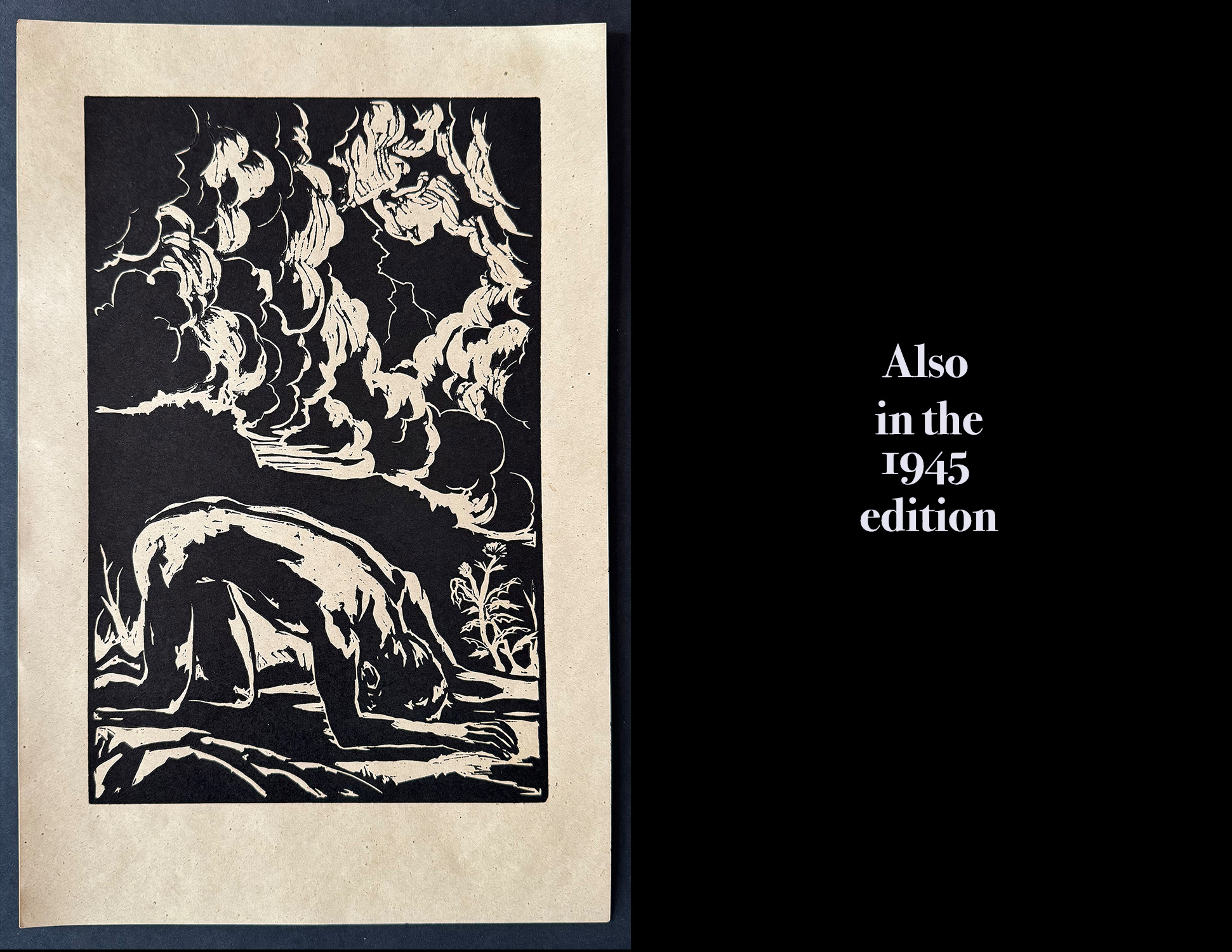

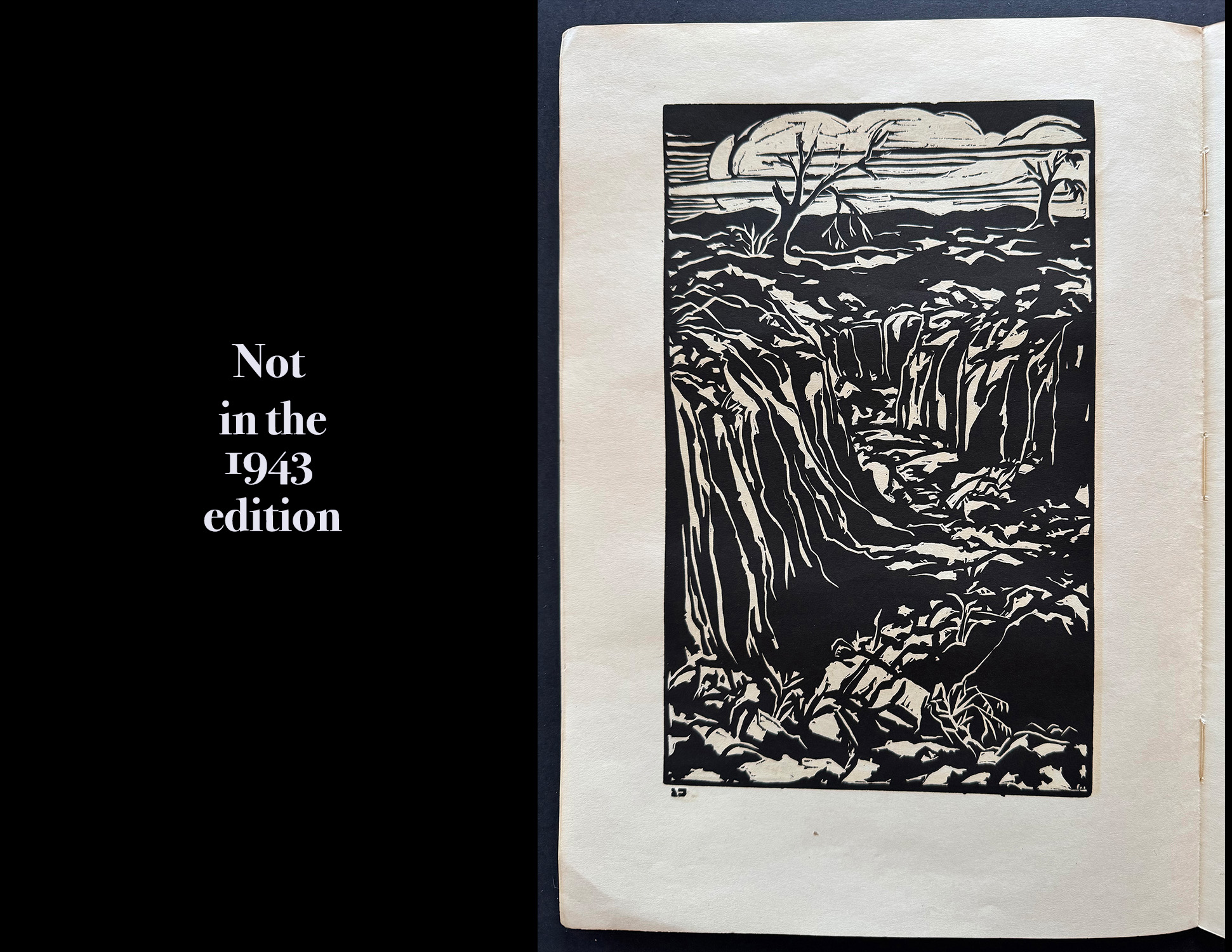

the Storm

Perry: “In ‘The Storm,’ his uncontrollable, ‘stormy’ feelings about the suffering abroad propel him to leave the comfort and security of his home and plunge into a hostile, nocturnal landscape…. In neither of these first two panels are the artist’s eyes open…. This inability or refusal to look, presented at the opening of the album, allows Glas to both acknowledge that he is not an eyewitness who saw the things he depicts with his own eyes, while also addressing the Nazi regime’s deliberate obstruction of vision by concealing or destroying their own extensive visual documentation. Vision is what Glas labors to imagine and image in the panels that follow.”

Contemplation

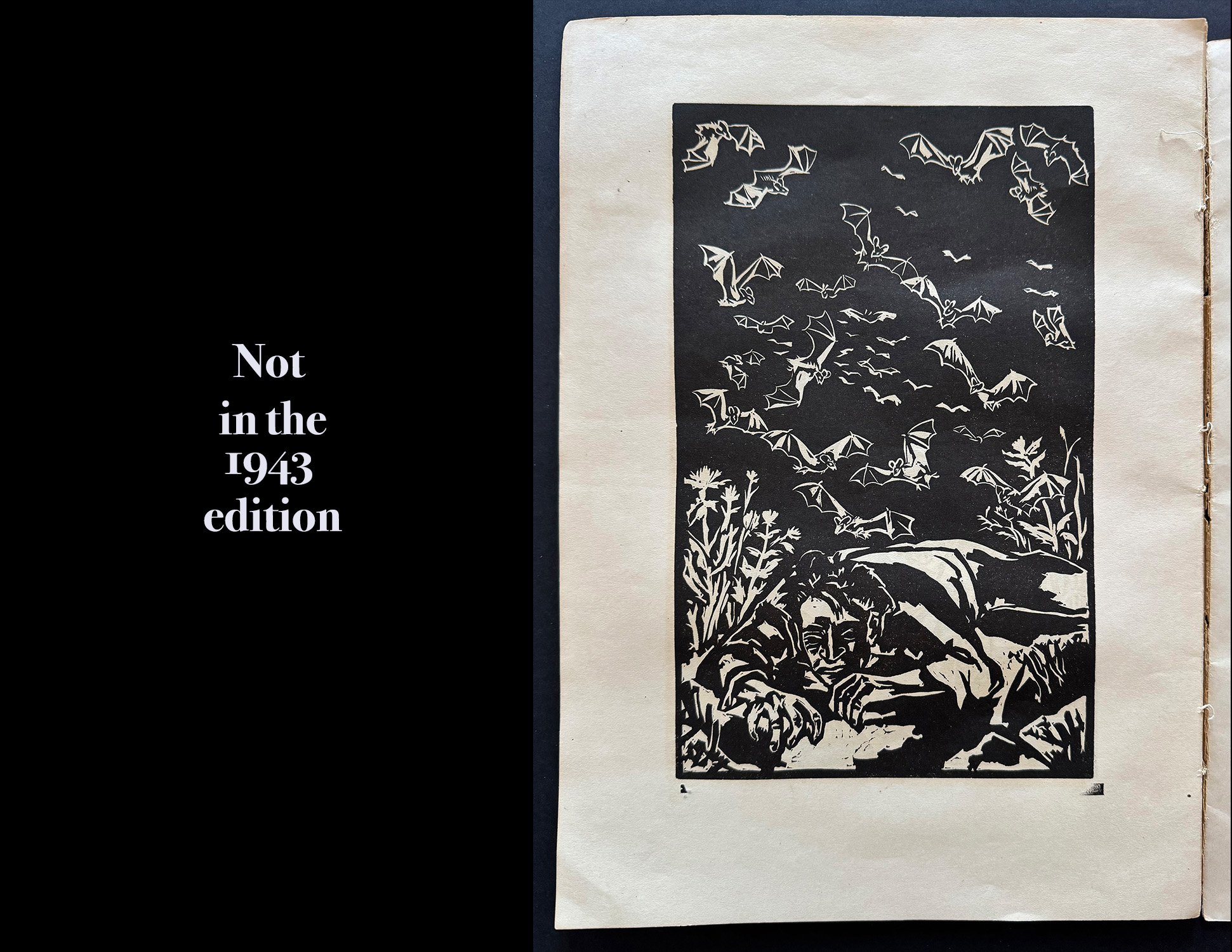

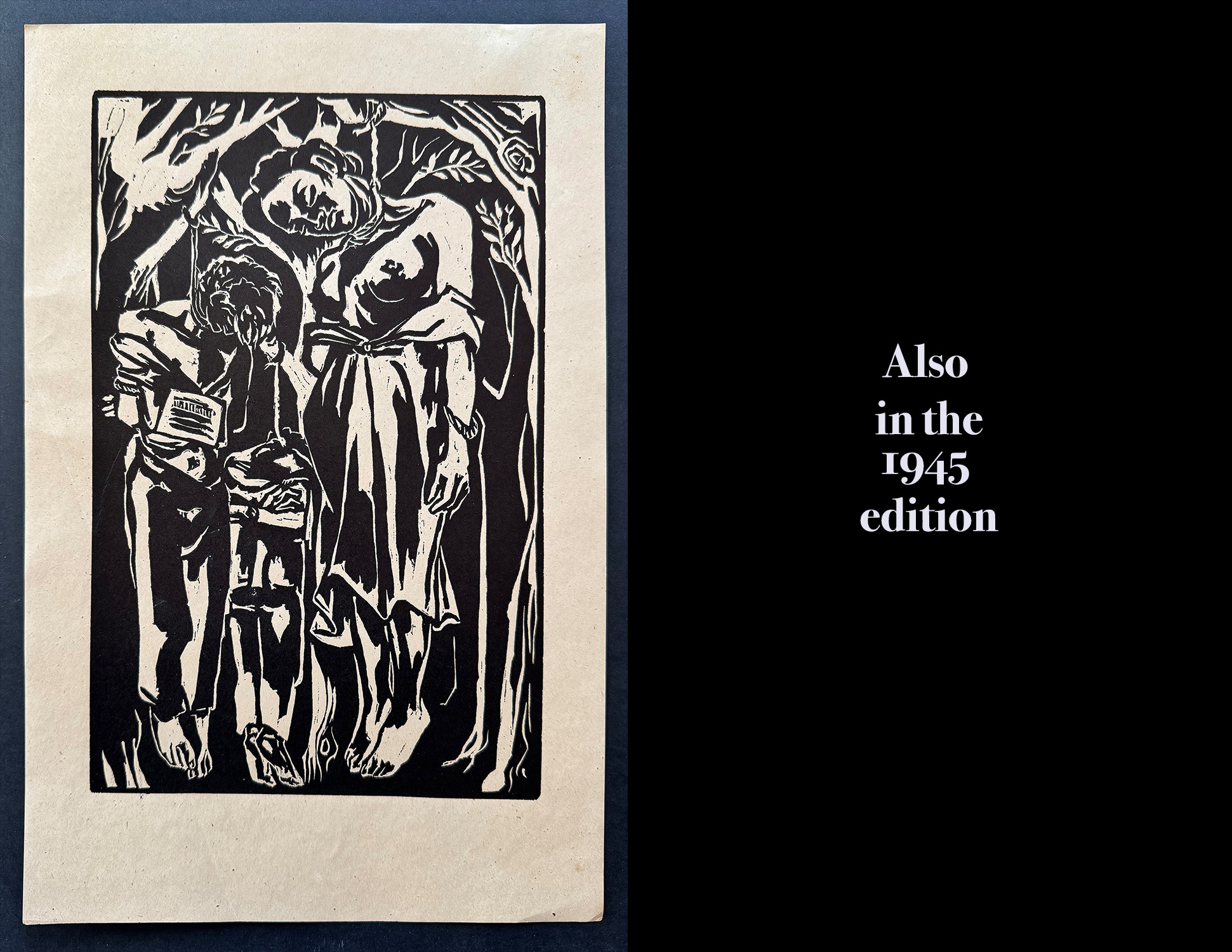

This is the first plate in the narrative that Glas added to the 1945 edition.

Perry: “ ‘Contemplation’ finds him prostrate, clawing at the ground to escape a cauldron of bats swarming overhead. Creatures of the night, these bats are pulled from Francisco Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, one of the earliest anti-war print cycles in European art, The Disasters of War.”

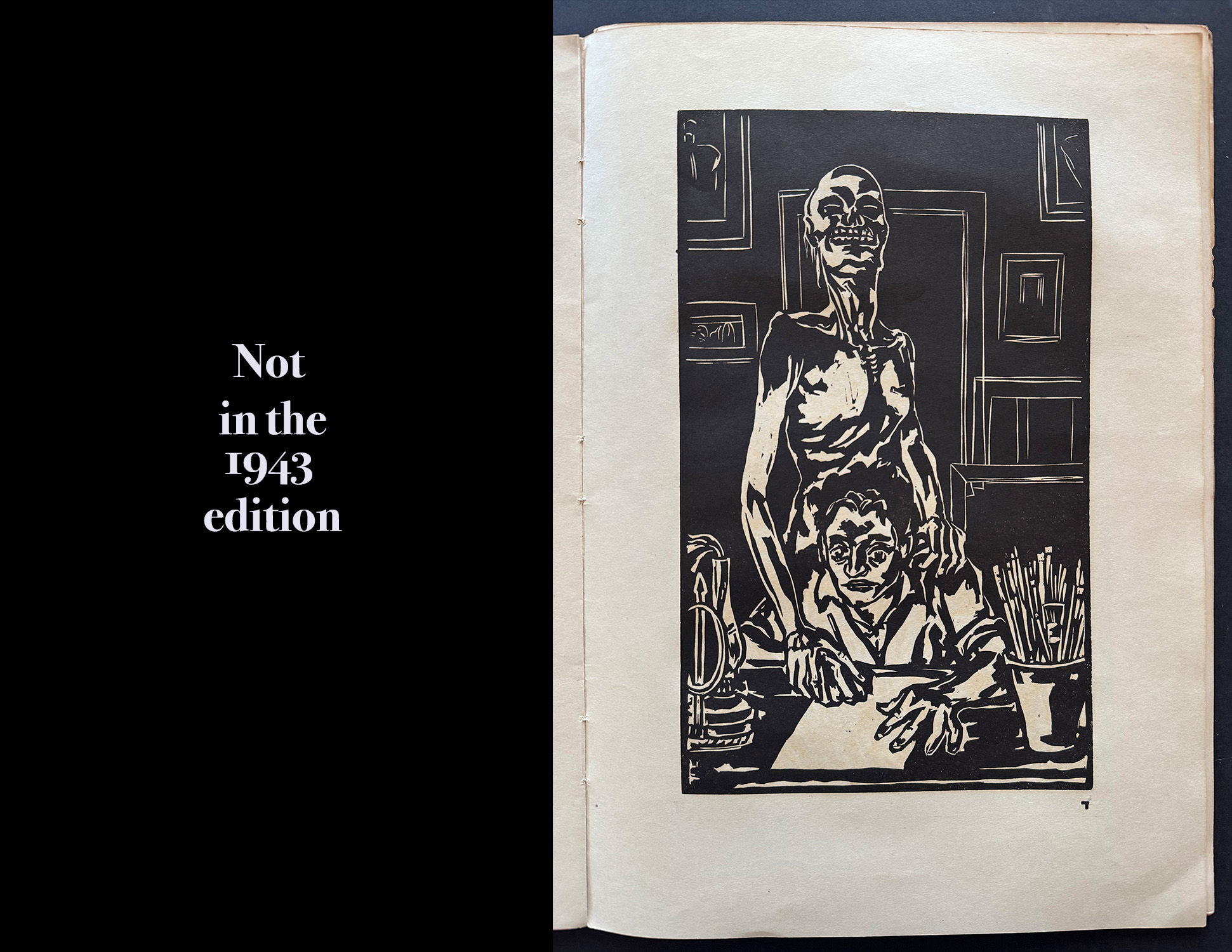

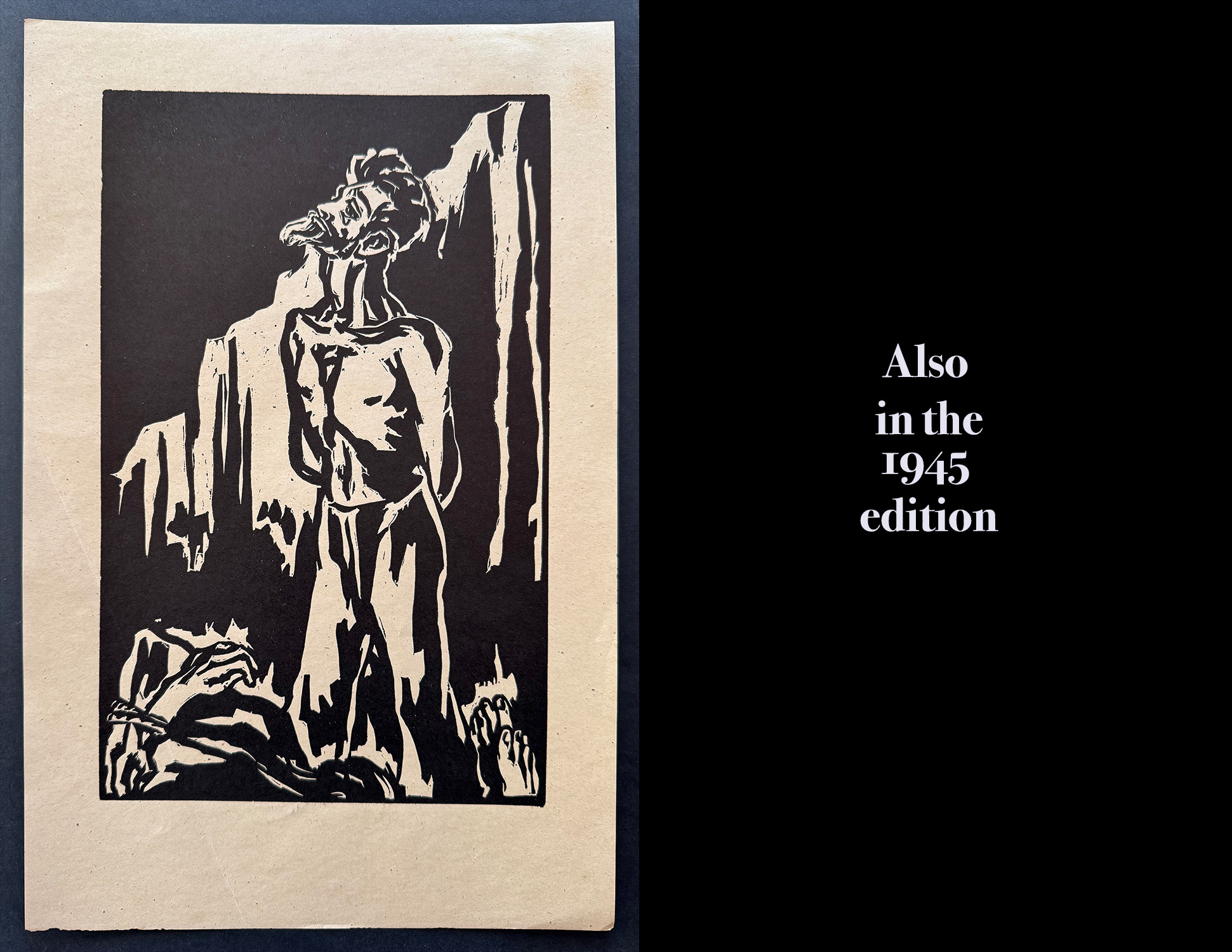

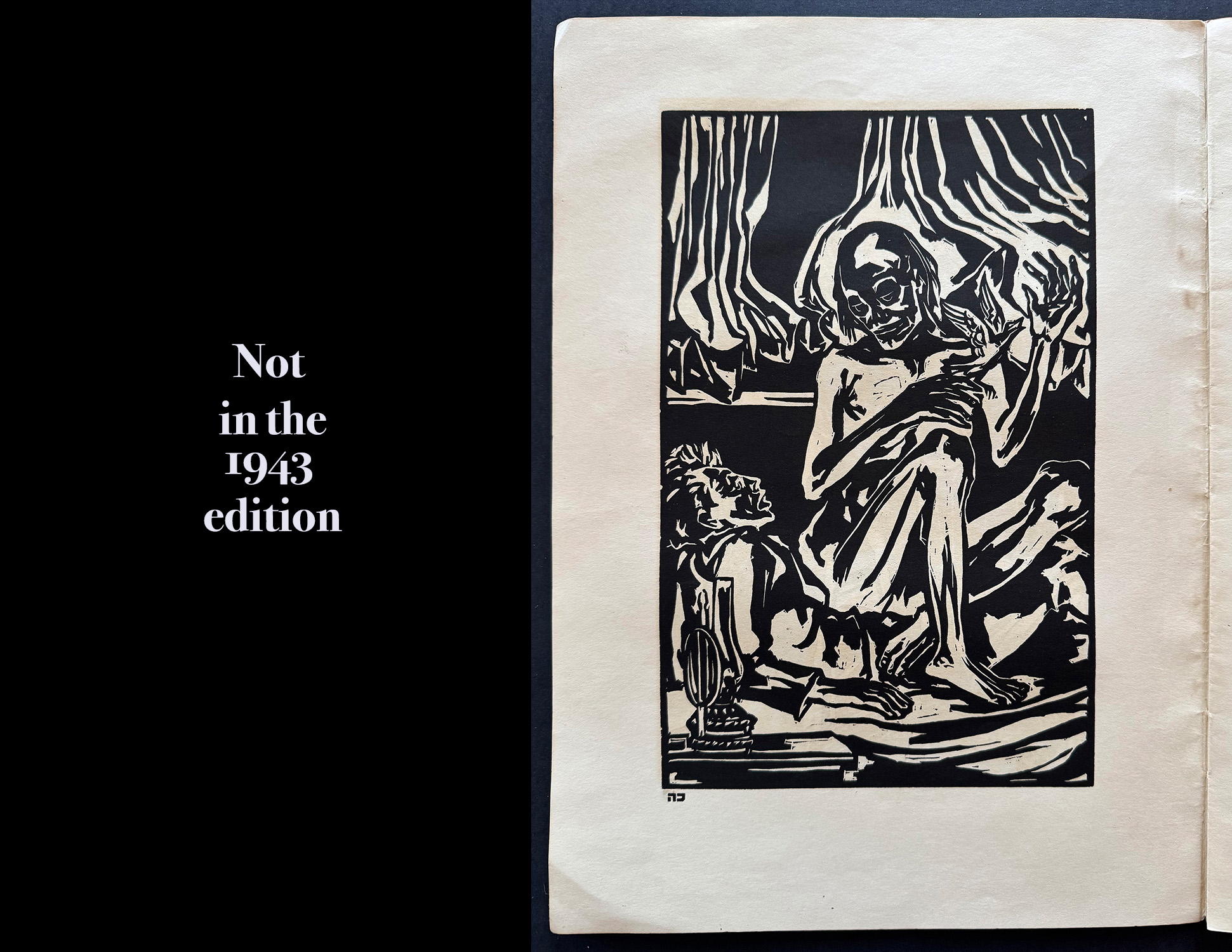

Death Speaks

Perry: “Although the first edition was subtitled ‘A Story Without Words,’ there is one figure who ‘speaks’: Death. In panel four, entitled ‘Death Speaks,’ the artist’s fear of death–the death of his loved ones and his people–materializes and takes form in the grimacing allegorical figure of Death who stands over him, pressing down on his shoulder and directing his hand. Glas represents himself as ‘Death’s secretary’; the artist becomes a medium who transcribes what Death dictates–like the medium of the album he creates.”

Ponemone: Glas must have thought that his first two linocuts didn’t provide enough framing between his own torments and those of Jews in Europe. Or as Perry has written: the story within the story. So “Contemplation” and particularly “Death Speaks” were his way of making that separation palpable.

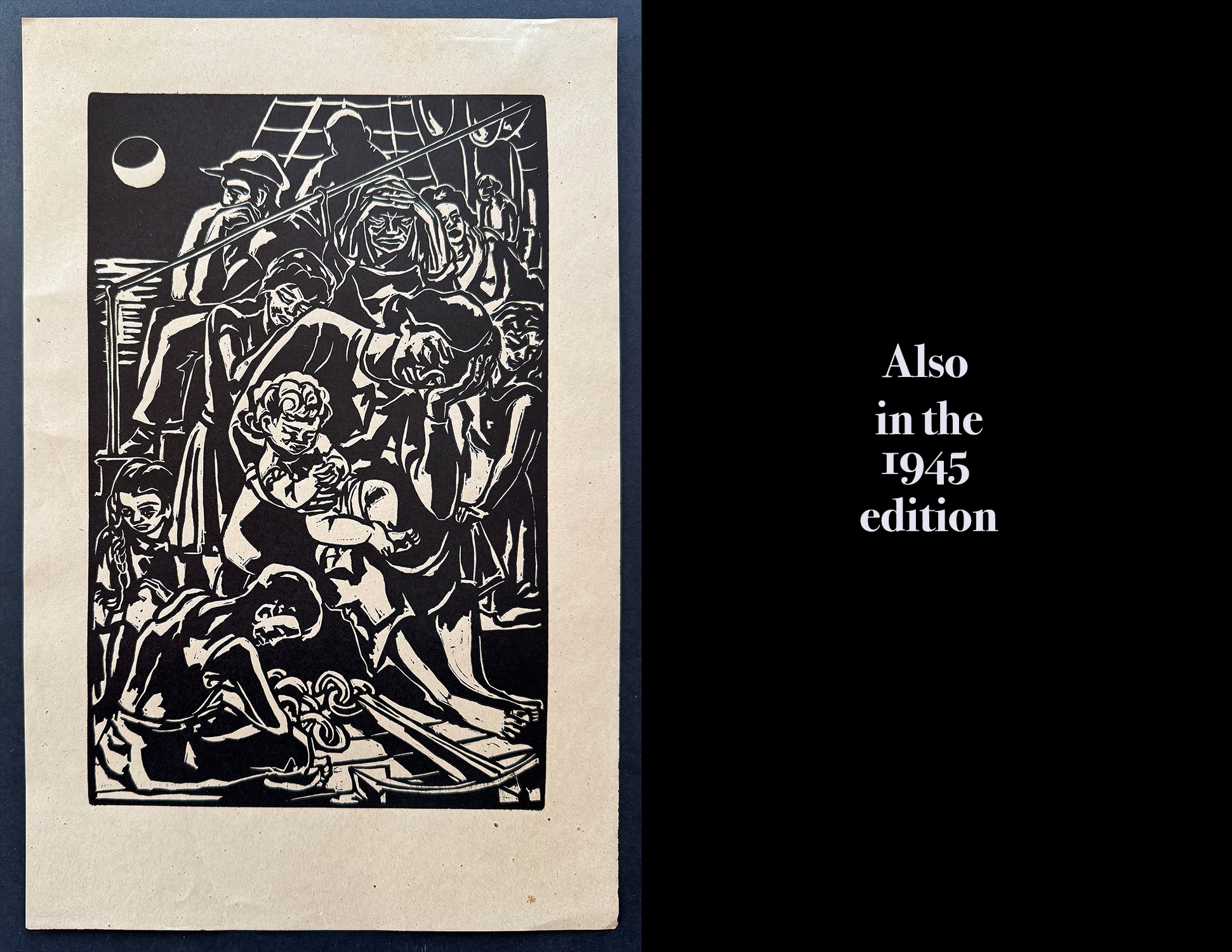

Refugees, called “Escape” in Hebrew edition

Perry: “After the fourth panel, we are pulled from Glas’ present in the Yishuv to events occurring far away in Europe and from the singular to the collective. The central panels of the book–its body–are given over to a montage of scenes of atrocity depicting the persecution, imprisonment, torture, rape, hanging, burning and execution of Jews on the Continent as well as those fleeing by boat and drowning at sea. Beginning with ‘Refugees,’ the narrative moves to ‘In the Flames,’ ‘Pogrom,’ ‘Rape,’ ‘Force,’ ‘Inquisition’ ‘In the Cellar,’ ‘Master Race (Herrenvolk),’ ‘Prison,’ ‘Concentration Camp,’ ‘Mass Shooting,’ ‘Burning of Corpses,’ ‘The Mother,’ ‘By the Side of the Road,’ ‘Against the Wall,’ ‘The Hanged,’ ‘Those Drifting on the Seas,’ ‘The End,’ and ‘Remains of Our Million Brothers.’ ”

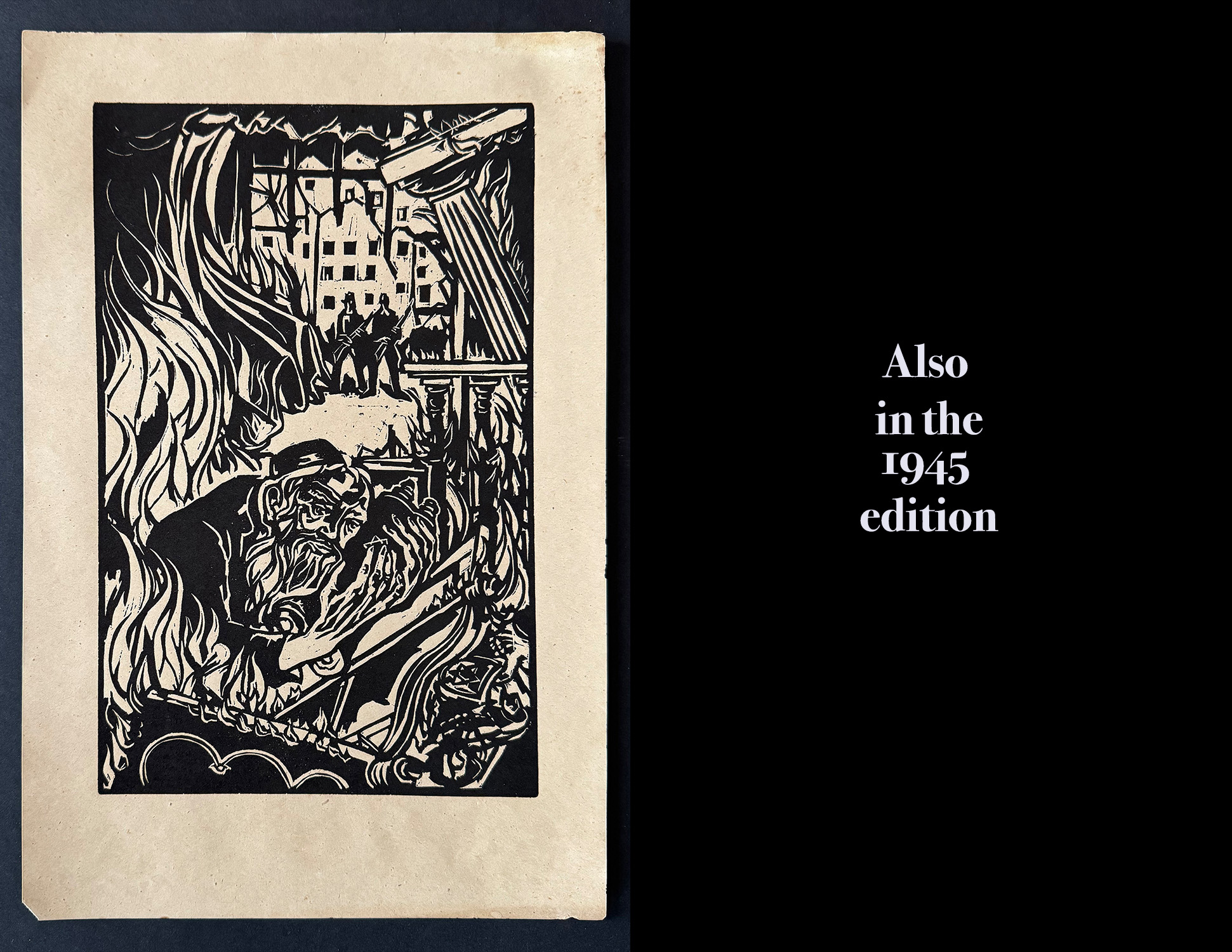

In the Flames

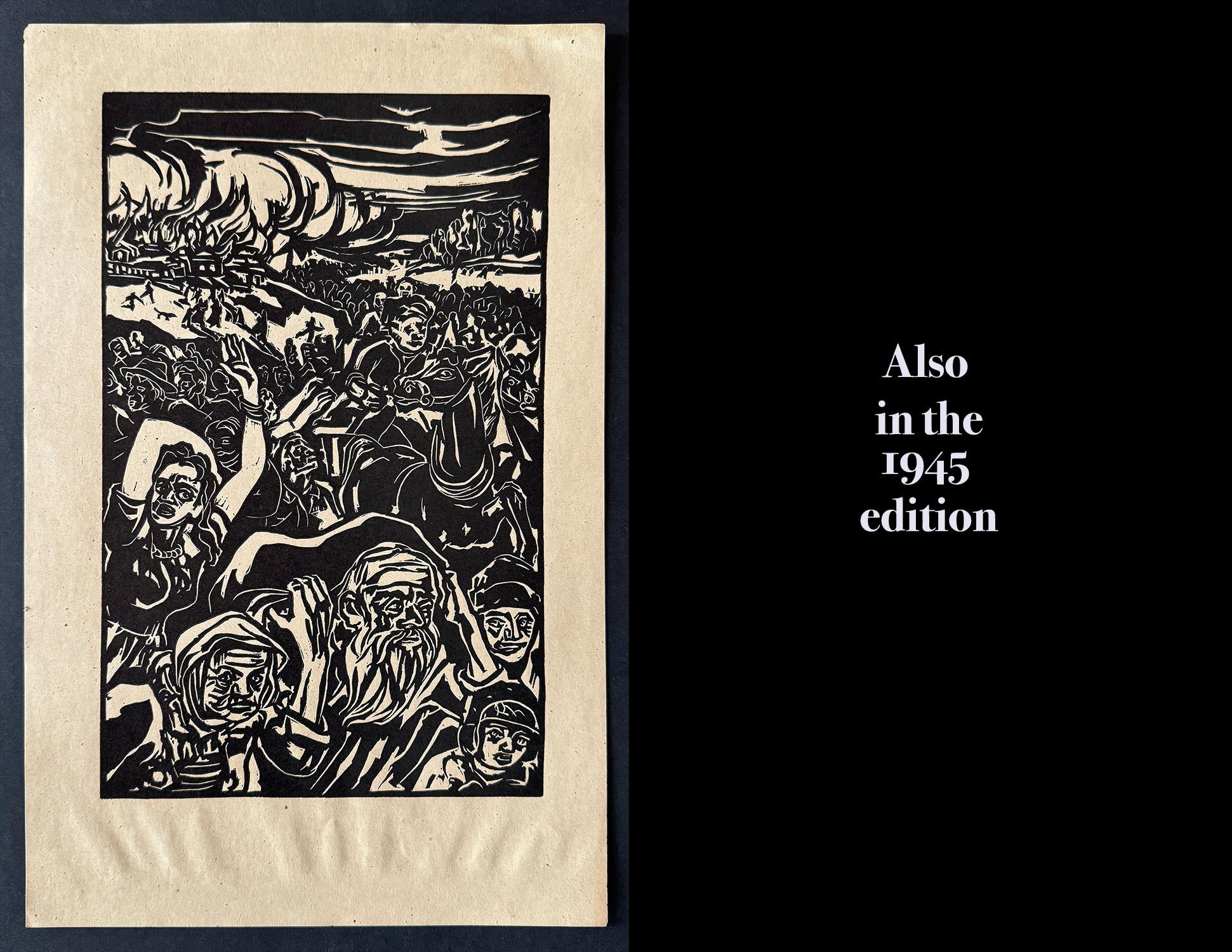

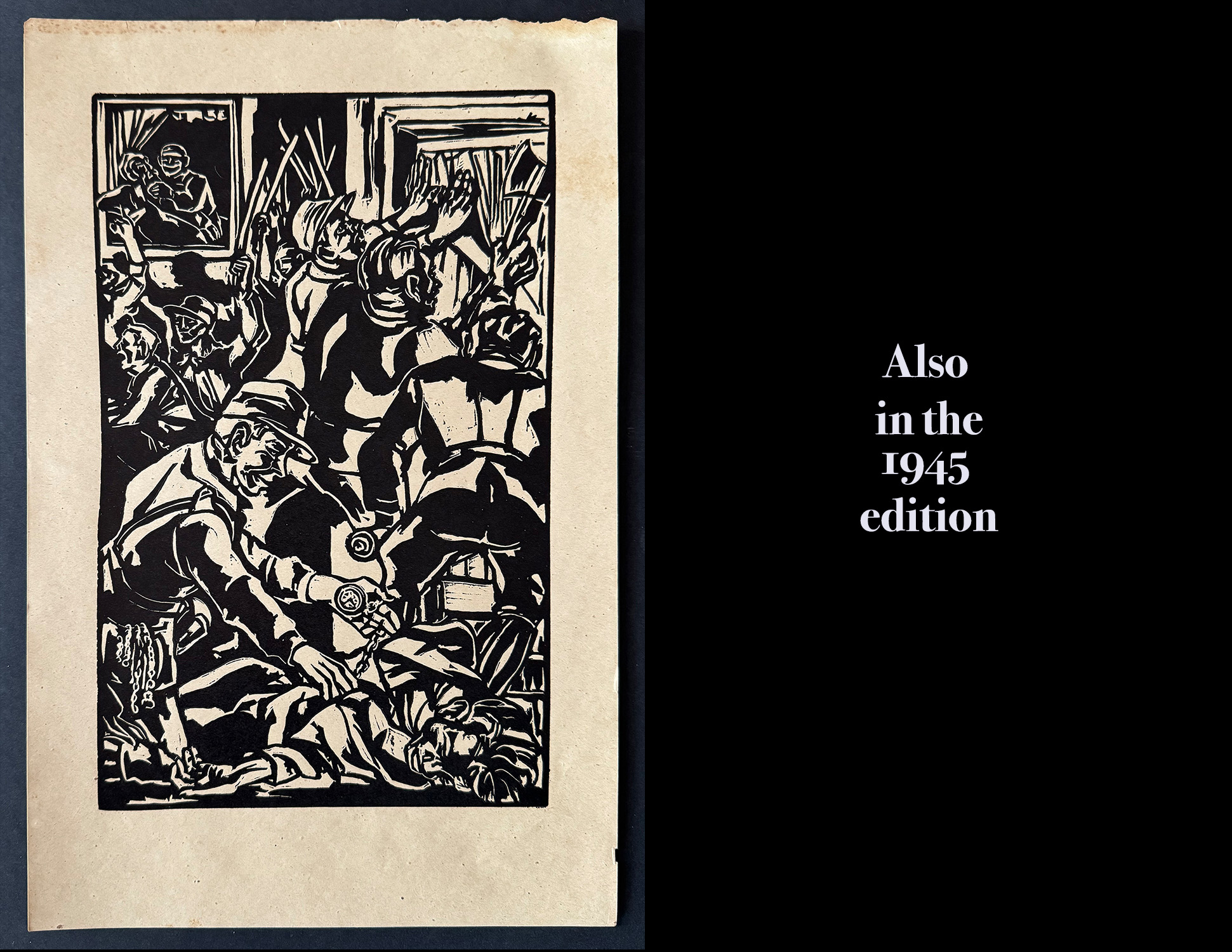

Pogrom

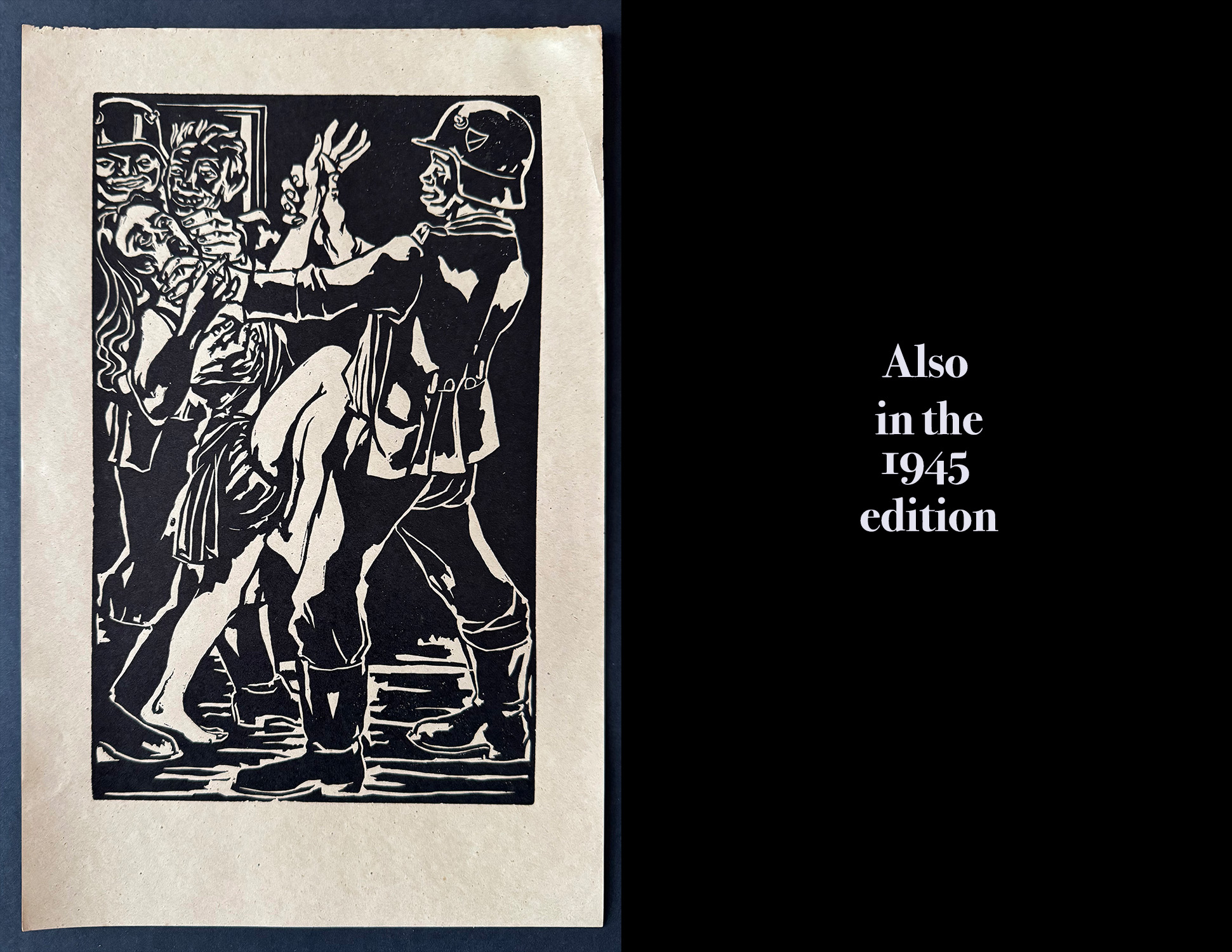

Force, called “Rape” in Hebrew edition

Perry: One way to describe what Glas is doing is telepathos. Nights not only depicts his own heightened empathetic identification with those suffering at a distance; it seeks to arouse the imaginative and affective engagement of his readers–despite the spatial distance that separates them…. Indeed, despite his physical distance from the camps, his work is not emotionally distant. Glas’ lack of distance is felt not only in the figures’ exaggerated expressions but in how close his figures are pressed to the picture plane; how the panels themselves are teeming with detail, offering no room or space to breathe; and how each image swells to fill the entire frame with the thinnest of white gutters around them.”

Ponemone: This plate in the 1943 edition was called “Force,” while Perry refers to it “Rape,” the title given it in Leilot.

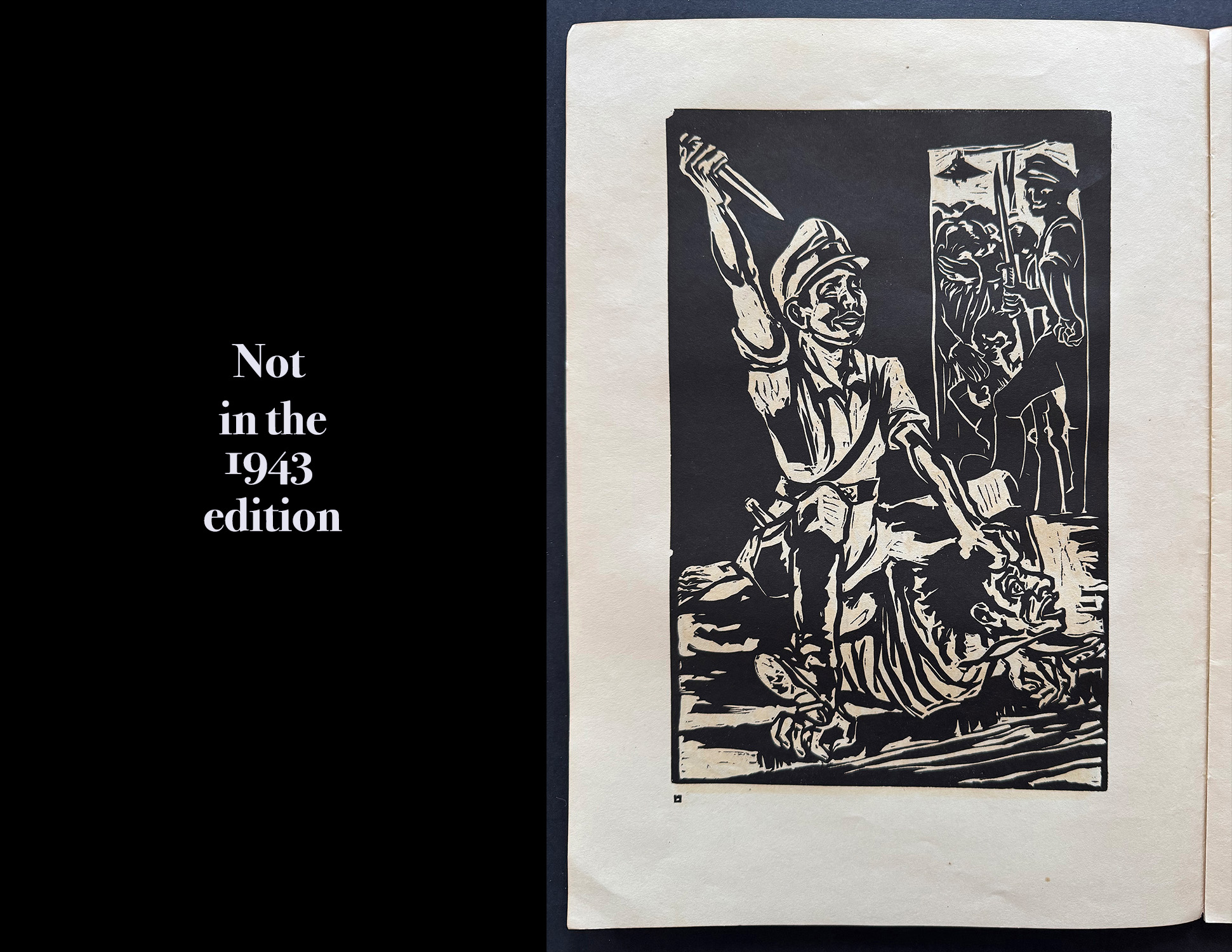

force

Perry referred to this image, which doesn’t appear in Through the Night, as “Force.” It was also called “Force” in my first Leilot blog.

Inquisition

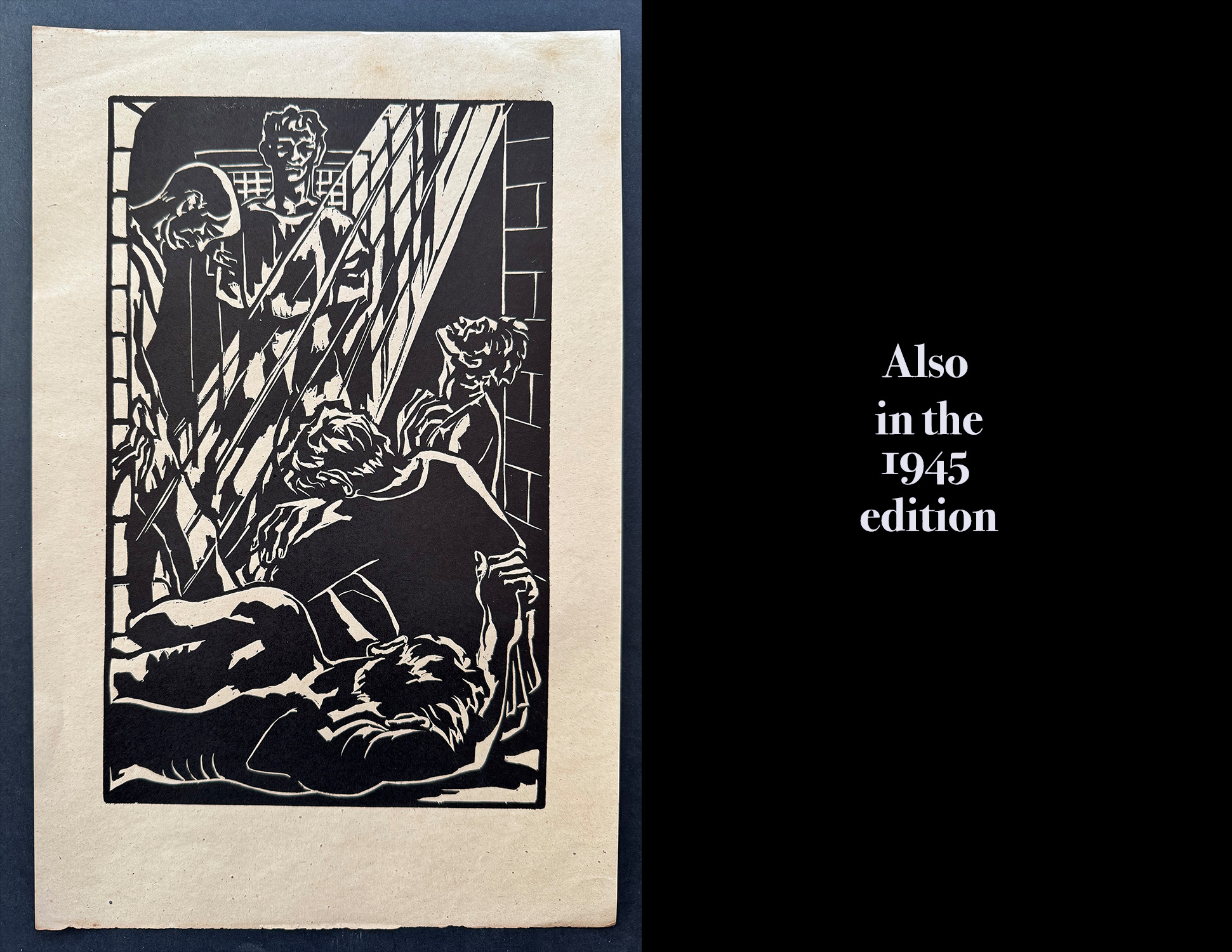

In the Cellar

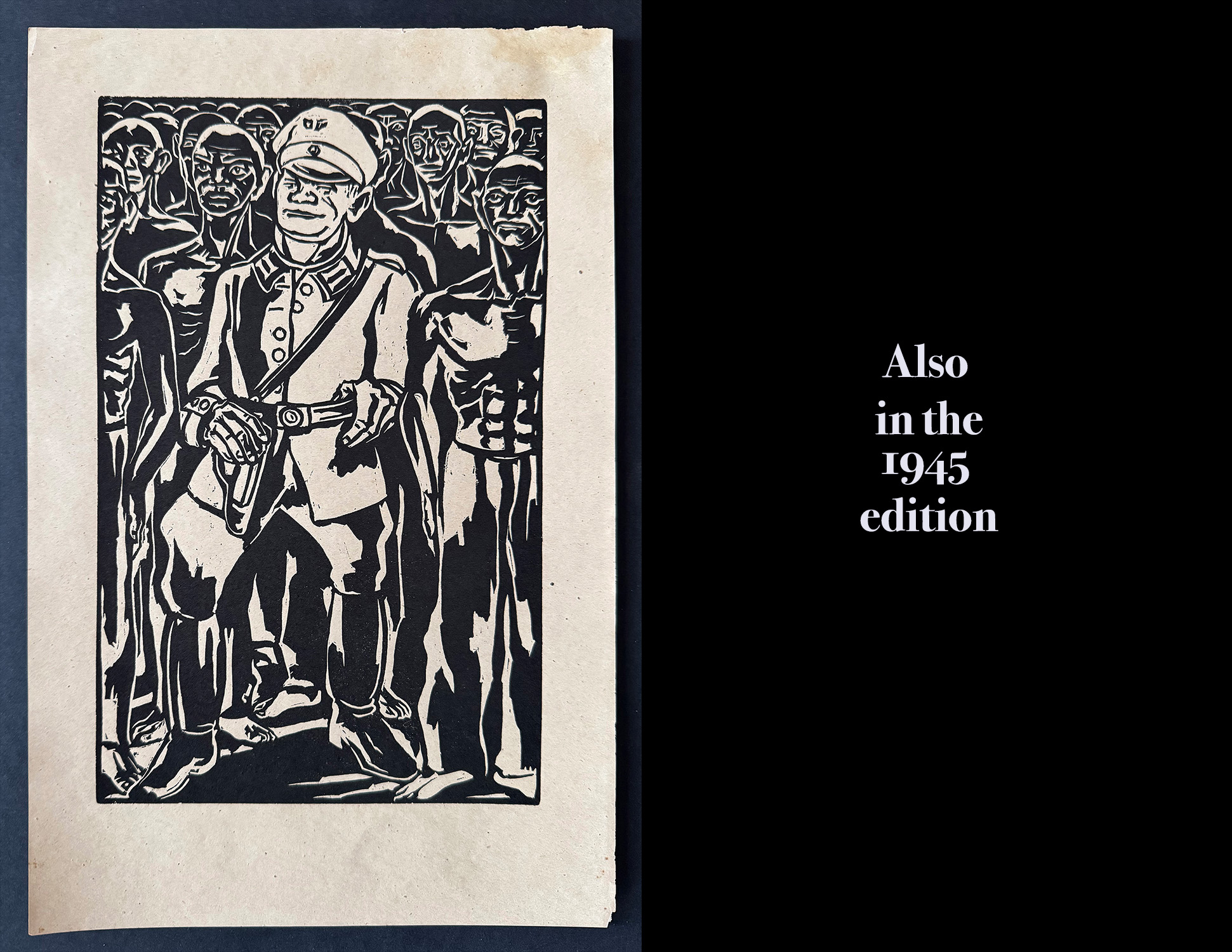

Herrenvolk (Master Race)

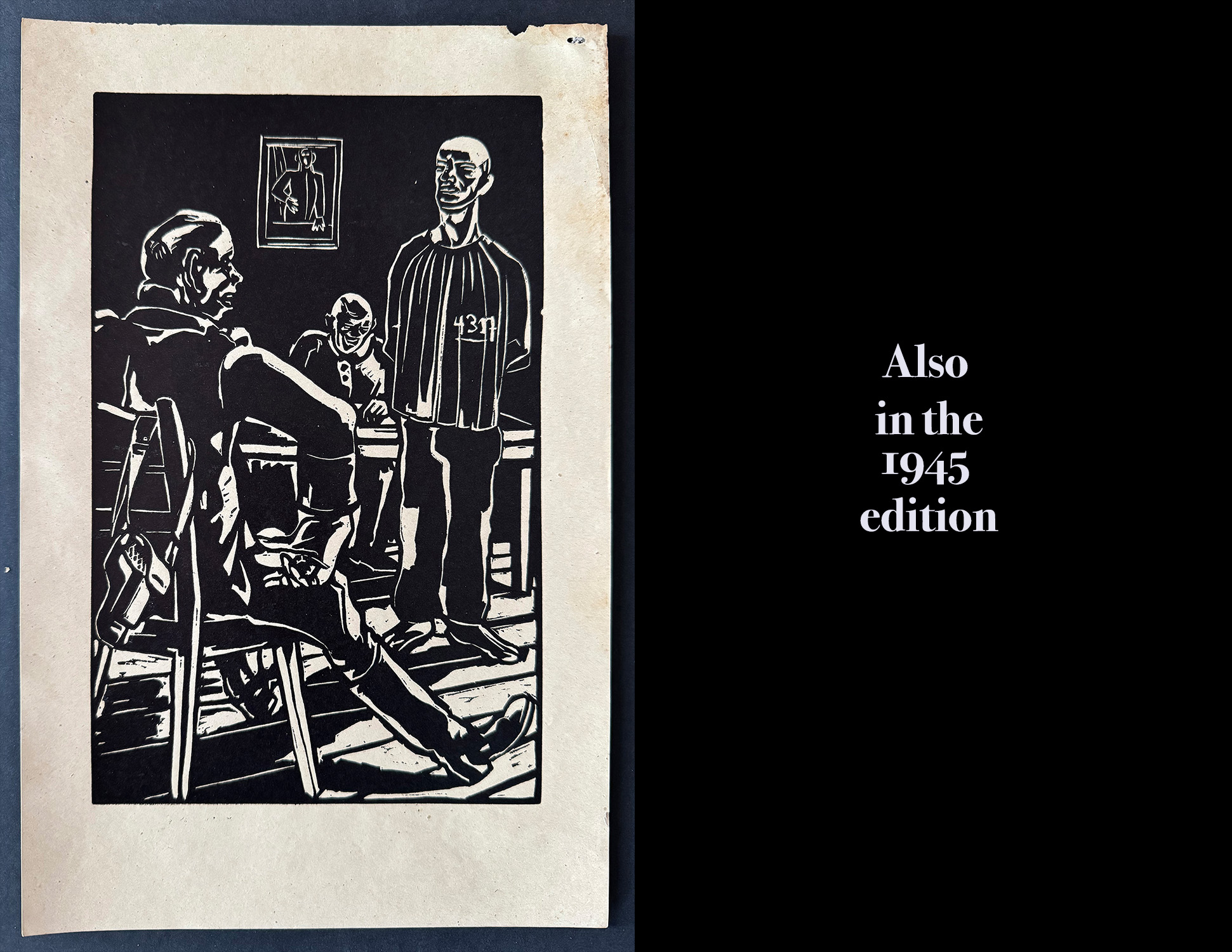

Prison

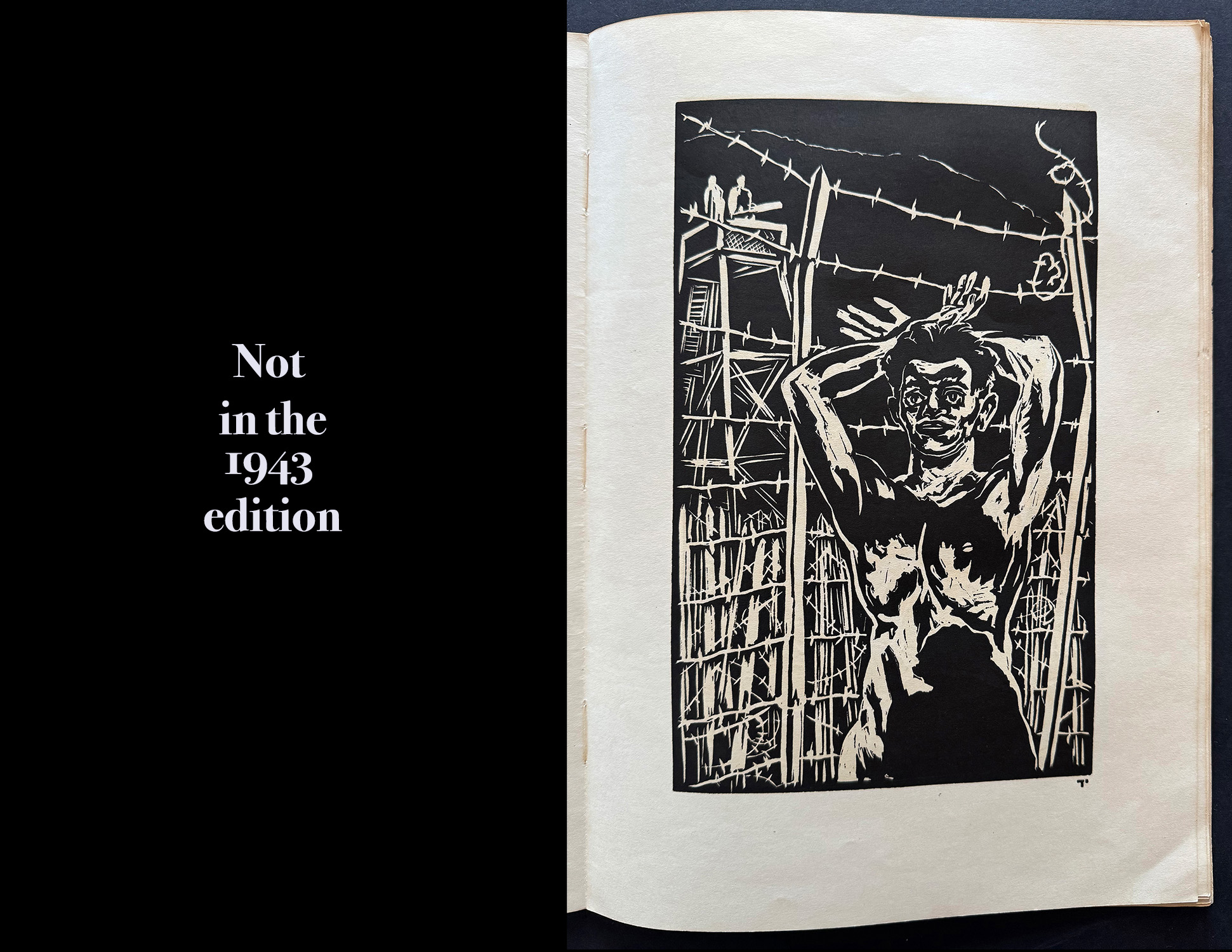

Concentration Camp

Perry in her article contends that this figure is a self portrait.

Perry: “But Glas goes further and projects himself into the victims’ experience by repeatedly inserting himself into the scene. In ‘Concentration Camp,’ he features a frontal, full-length self-portrait of himself within a camp: his arms bound behind his head, stripped naked and surrounded by the tangled coils of a barbed wire fence and surveilled upon by two officers and their machine gun in a distant watchtower.”

Since I didn’t make that self-portrait assumption on viewing this plate, I decided to ask both Iddo Gal and Hagar Lev.

Iddo Gal: “But for me, the answer is 98% “yes”…. I rely on visual evidence – see attached #1, I put side by side the photo from Leilot, and a photo of Erich and his wife Susi, taken somewhere in the ’30s. (It is from a B&W photo album of one of the relatives from the Adler family, Susi’s side). I surmise it is from before he moved to Palestine in 1934, because of the tie and what looks like a white shirt (nobody in Yagur dressed that way back then).

“The visual resemblance between the photo and the Leilot figure is quite striking, in particular when you note and compare:

(a) the hair contour on top (lots of wavy hair),

(b) hairline upfront (with a little point going down in the middle),

(c) the nose,

(d) the triangular shape of the face (starting pointy at the jaw, expanding upwards).”

Hagar Lev: “Me too. To add one more point on this: As we know it, the story of Leilot was conceived when Erich was lying sick with high fever and hallucinating, waking up from a nightmare, putting in on paper. Like the tortured artist in the first frames of Leilot.”

And at my request Perry added this to the conversation:

She wrote: “I think we can all agree that the beginning and the end sections are self portraits, featuring Glas himself. The frontispiece and panels 1 (although his face is covered), 3 and 4 figure the same person–a man in Palestine. This man reappears at the end, when he escapes the horror on the continent in panel 24 until the end. Same hair, same facial features.

“The question you pose is whether he (Glas) is in the central portion, when the story shifts to Europe. I see the same (or similar) figure at the bottom of panel 7 (Pogrom), maybe 8 (In the Cellar), 14 (Concentration Camp), possibly mauled by animals in no. 16 and dead on the ground in no. 17…. Can I prove it? No. The male figures in the middle section could represent a Jewish “everyman” or doppelganger. But they look enough like the man in the opening and closing sections to suggest my reading.

“It is true that the ‘autobiographical’ element is stronger in the later edition, given the added panels with the figure of Death. For me, the insertion of a man who uncannily resembles the author/artist allows Glas to show that this is something personal, that is happening to people that look like him (whether or not it is actually him) and not only to religious Ostjuden like the one in the Kristallnacht panel. To see himself in that event/story, like the Passover Seder where we are given the injunction: בְּכָל-דּוֹר וָדוֹר חַיָּב אָדָם לִרְאוֹת אֶת-עַצְמוֹ כְּאִלּוּ הוּא יָצָא מִמִּצְרַיִם, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר

” ‘In each and every generation, a person is obligated to see himself as if he left Egypt.” This is the imaginative leap (or empathy) he makes.”

Ponemone: I dare not ask if Glas used the countenance of anyone else, particularly his wife, from the kibbutz for his wordless narrative. See the face in “The Mother” in a plate coming up.

Mass Shooting

Burning of Corpses

The Mother

By the Side of the Road

Against the Wall

In the 1943 edition this image appears right after “Mass Shooting,” which would have been appropriate since it’s a closeup of one man before the firing squad. But in the 1945 edition it is separated from “Mass Shooting” by three new images.

The Hanged

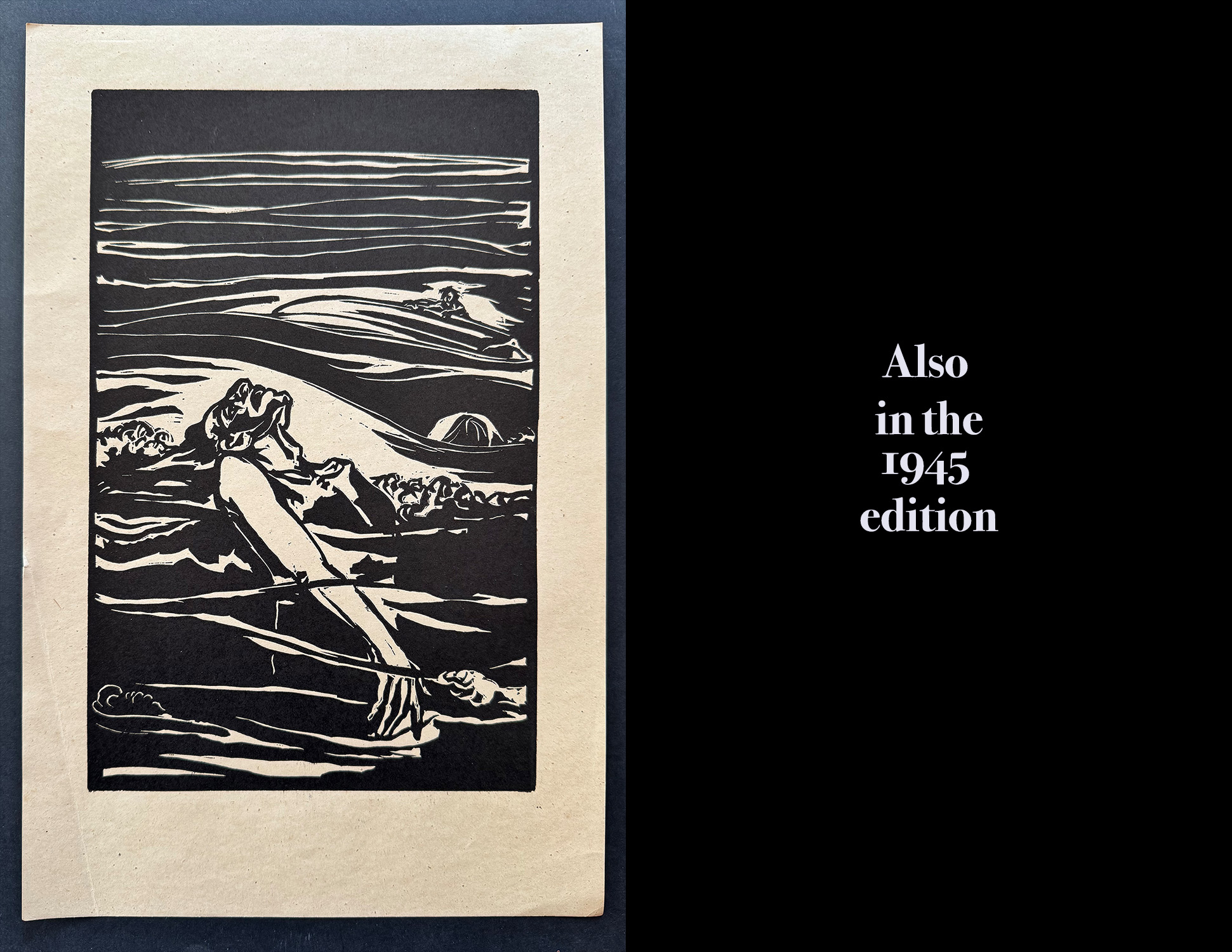

Those Drifting on the Seas

The End

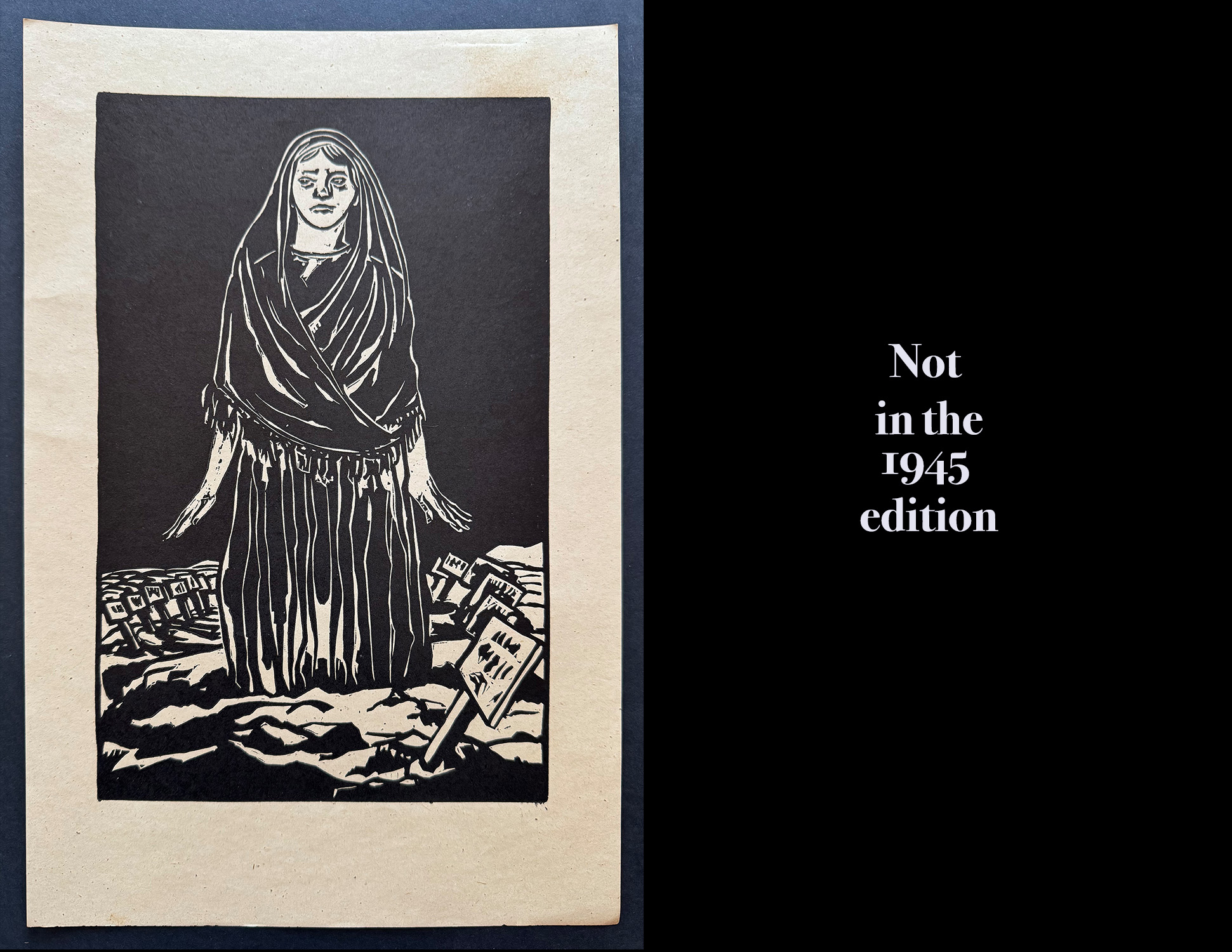

The Woman

Glas decided to drop this plate from the 1945 edition. This stiff rendering of a woman between rows of grave markers doesn’t portray a woman’s grief and tenderness as well as the new plate “The Mother” six plates earlier in the 1945 sequence. In Through the Night this plate marks the end of the Holocaust sequence.

Remains of our million brothers

In Leilot this plate marks the end of the Holocaust sequence.

Where to?

Perry: “After ‘Remains of Our Brothers,’ [in Leilot] the narrative cuts back to his present in the Yishuv. Five panels follow–a coda of sorts–in which the artist/protagonist returns. In ‘Where To?’ the artist flees, arms outstretched, away from the disaster.

What do you Fear?

In Leilot Glas reintroduces Death, who releases a dove.

Perry: “In ‘What Scares You?’ the artist is shown back in his room, quite literally “wrestling” with Death, who has pinned him down, crushing his chest.”

But Perry doesn’t mention the dove in her essay. So I asked her about it. She responded: “It makes an appearance in the earlier edition too, in the very last panel [see “The New Dawn”] where it takes flight, silhouetted against the sun rising over Eretz Israel and directly over the skull (which becomes a full-fledged anthropomorphized Death in Leilot). So there is already this relationship set up between the dove and death….

“Death releases it but appears to threaten to squash it with its upraised left hand. Perhaps this is the answer to the title’s question: What Glas fears is that Death will destroy any chance of peace. Ironically, this moment, or this realization, is what prompts Glas to take up arms and protect his people, his land.”

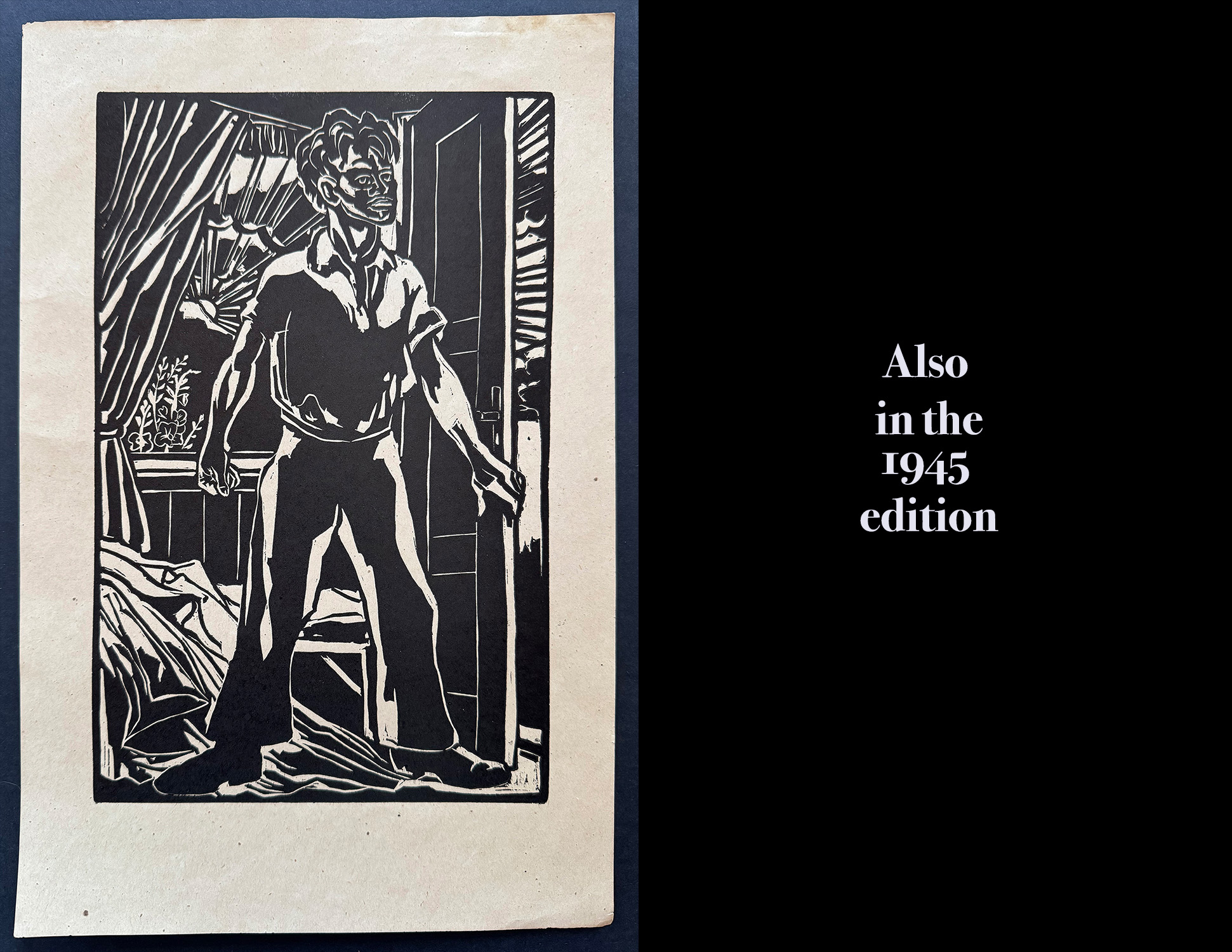

Arise!

Perry: “Finally, throwing off the weight of Death, the artist stands upright and resolute in the panel entitled ‘Arise!’; his fists clenched, his jaw set, his will firm, he opens the door to the sun rising on the horizon.”

To Arms!

Perry: This plate “shows him trading his stylus for a rifle and joining a community called to resist.”

And fight for freedom

In the index in the English 1943 edition, this plate is listed as “And Fight for Freedom,” but Perry calls in “New Dawn,” which is the name used for the following plate only found in the 1943 edition.

Perry: “In the ‘New Dawn,’ the sun is rising behind the masses assembled: in other words, they face northwest, towards Europe. They are taking up arms to go and fight off the Nazis.”

In summary, Perry wrote: “Nights was not–or not only–created to exorcise his own ghosts or to relieve his conscience; it was intended to prompt empathic concern by moving others to take a collective stand. Indeed, Glas’ imperative command ‘Arise!’ was directed at his readers. Nights thus ends by replacing the private lament of the individual with the collective song of a people. The throng of men and women singing are led by the artist; it is his work that assembles this emotional community–a vocal community, crying out in unison, thereby channeling emotions into actions.”

The New Dawn

The final plate in Through the Night from 1943 reframes the cartouche on the title page. The skull returns, but no rose grows from a socket. Instead it’s surrounded by cactus. In the middle ground if bucolic scene of a field is being plowed near a village. The Sun above repeats the sphere of the skull but, in conjunction with the upward flight of a bird, is a sign of life.

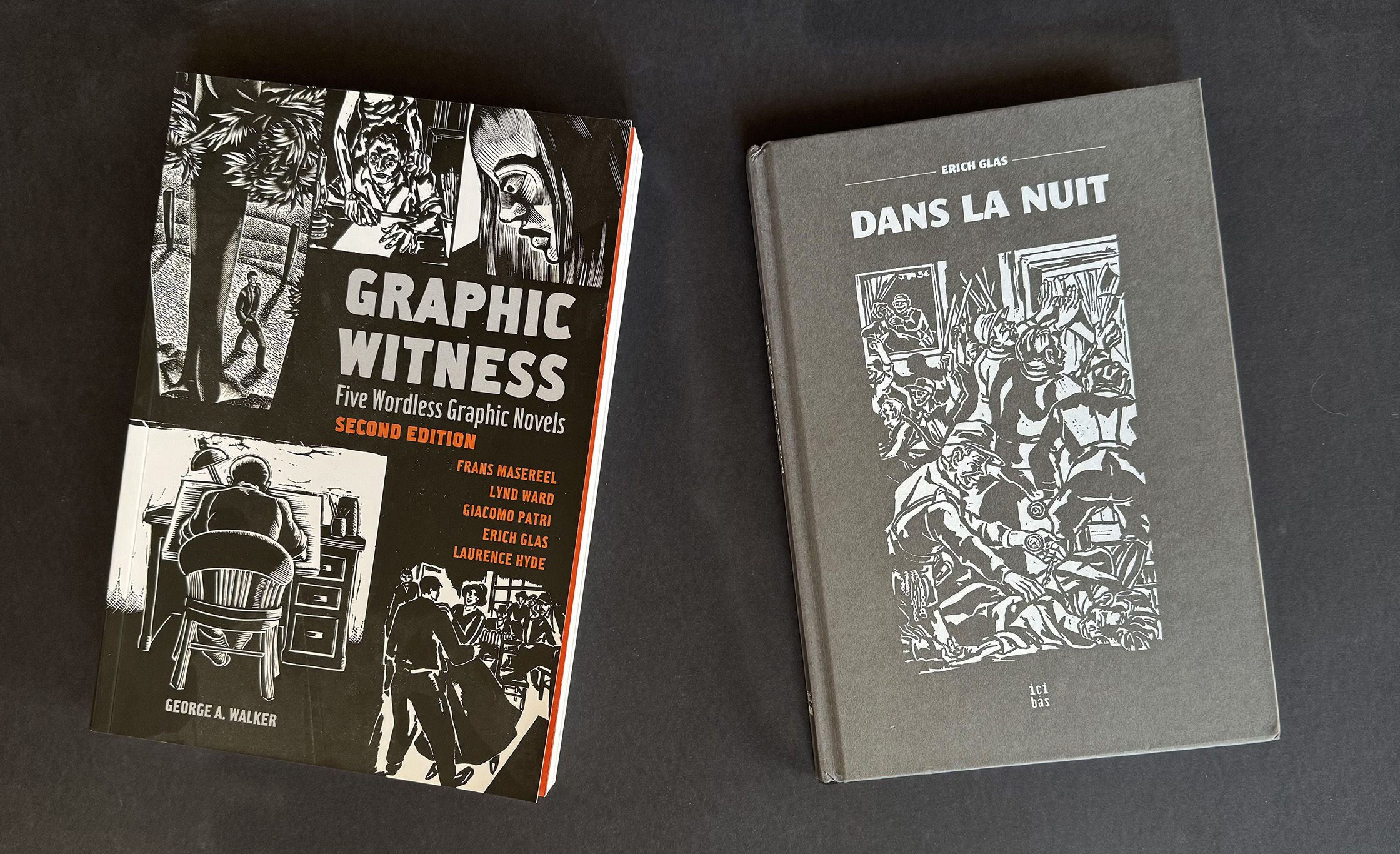

New Publications

Since my October 2018 blog post on Leilot, Erich Glas’s dramatic wordless narrative has reached a wider audience via the publication of these two books.

I’m honored that I helped facilitate the inclusion of Leilot into the 2021 second edition of George A. Walker’s Graphic Witness (Firefly Books, Toronto, Canada). Walker has a remarkable history for creating woodless narratives told with his own wood engravings. (His website: LINK) Graphic Witness was first published by Firefly Books in 2014. In it Walker reprinted four graphic novels by artists who were celebrated in the 20th century for their stories entirely told in relief prints. Included were works by Frans Masereel, Lynd Ward, Giacomo Patri and Laurence Hyde.

Walker contacted me in 2020 and asked if I had any suggestions for a second edition of Graphic Witness. I immediate connected him with Hagar Lev and Iddo Gal, who were most receptive to including Leilot. Walker then kindly asked me to write a short essay for the second edition.

Then in 2022 Leilot reached the Francophone world under the title Dans la Nuit (Editions Ici-bas). Both Lev and Gal created this publication and wrote a lengthy essay describing their grandfather’s life with many images of his prints and photos he took of Kibbutz Yagur.

★ ★ ★

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/erich-glas-through-the-night-vs-leilot-nights/trackback/