Eretz Israel: Narratives in relief prints

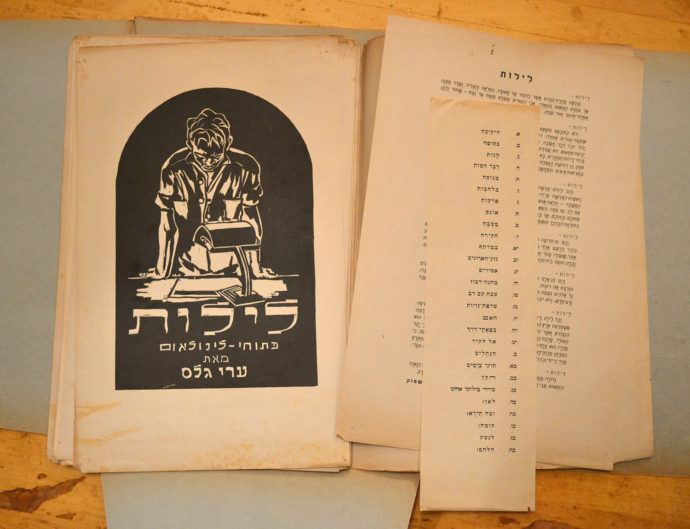

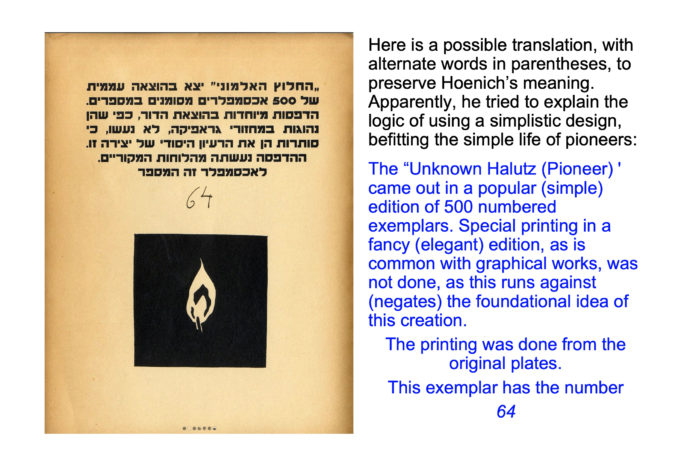

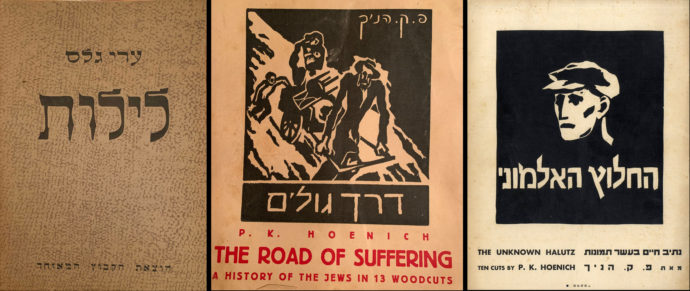

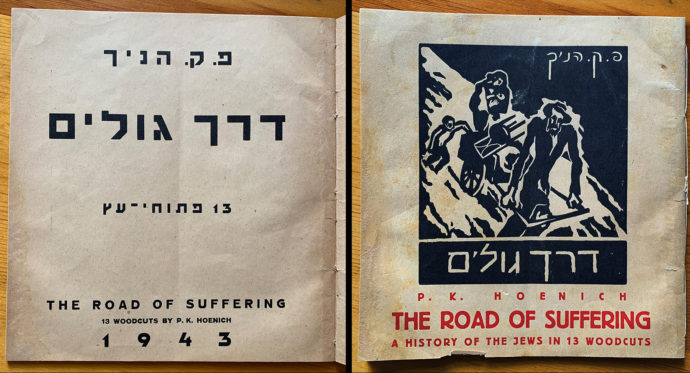

The covers of (from left) Erich Glas’s “Leilot,” P. K. Hoenich’s “The Road of Suffering” and “The Unknown Halutz.”

Introduction

Even as a seasoned print and book collector who tries to maintain his focus, I never know where my collecting jones will take me. And this blogging business has certainly been responsible for some interesting left turns. Take, for instance, the sequence that began when Aesopische Fabeln (Aesop Fables), 1920 portfolio of wood engravings by Erich Glas (1895-1973), appeared on eBay. It was a perfect fit for my interest in wordless narratives and edgy relief prints. I soon was able to secure at great savings a copy from a Swiss book dealer. As a result I blogged about it in May 2018. (See http://www.scottponemone.com/fables-erich-glass-prints-add-to-genre/)

Then Hagar Lev, a granddaughter of the artist, discovered that blog post and contacted me. Soon she and another Glas grandchild, Iddo Gal, were in contact and a lengthy email dialog ensued, which for me culminated in their sharing a video of someone leafing through Erich Glas’s Leilot (Through the Night, 1945) with its sequence of 28 linocuts about the horrors of the Holocaust and the need to tell about them in pictures. (“Leilot” was initially published in South Africa in 1943 with fewer images.) That story was told in an October 2018 blog. (See http://www.scottponemone.com/leilot-erich-glass-traumatic-creation/) This second Erich Glas post provided a lengthy biography of the artist.

I lived with the fact that Glas descendants (all eight surviving grandchildren) were unwilling to part with a copy. (It was unusual for me to blog about artwork I didn’t own.) But then I came upon an eBay offering from a bookseller in Israel. It was a copy owned by an Israeli youth group. It had been unbound, the plates separated with signs that they had been displayed using thumbtacks. The covers were mounted on the front and back of a custom-made portfolio that housed the plates and Hebrew text. That story was covered at the start of another blog posted in December 2019. (See http://www.scottponemone.com/update-2019-print-acquisitions/)

I kvetched to the seller–J-B from the bookstore in Israel–after that copy arrived. As you can see there was some discoloration, a few plates had tears or small losses at the corners. His response:

The portfolio Leilot is indeed a genuine rarity but I have a suggestion–If in time I’ll be lucky enough to put my hands on a better copy, Before Offering it to other collectors or listing it on eBay–I’ll give you the right of 1st refusal–I’ll sell you the better copy while the payment you’ve made for the 1st copy will be considered as a down payment and then you’ll have the better copy and return the 1st one to me. Not very likely to happen but not absolutely impossible.

Needless to say, the reason for this fourth post on Erich Glas was because the dealer in fact ran across a very good bound copy and offered it to me in January 2020. Negotiations for this intact copy soon involved another wordless narrative by a Jewish artist: The Road of Suffering (1943) by Paul Konrad Hoenich (1907-1997). In his sales pitch J-B wrote:

As for the other book–You can’t ignore the similarity–these are almost twins. Both artists, Glas and Hoenich, were of Eastern/Central Europe descent with families which were left in Europe. They both were immigrants who lived in Eretz Israel (Palestine) and created these publications in midst of the Holocaust 1943-1944 while the Israeli politics, culture and population were sunk in extreme denial and the atrocities were no more than rumors. They both acted in the far margins of the main stream of Eretz Israeli art. They both created a very limited number of publications and in a very limited editions and they were both cutters: linocuts and woodcuts.

So let me first briefly introduce the intact copy of Leilot, then provide a complete presentation of all the plates in The Road of Suffering.

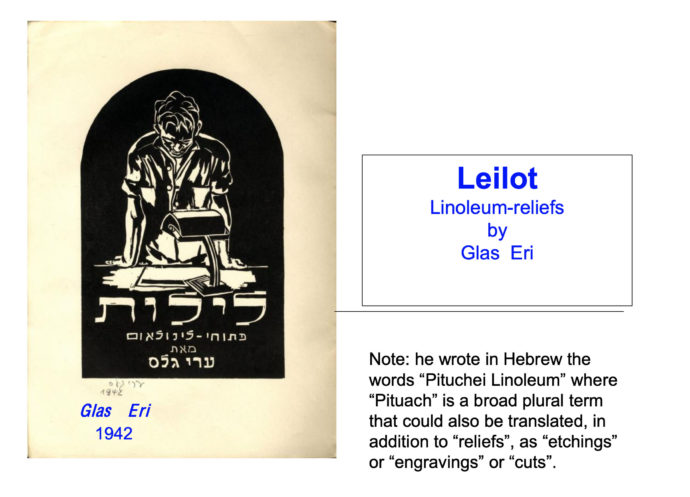

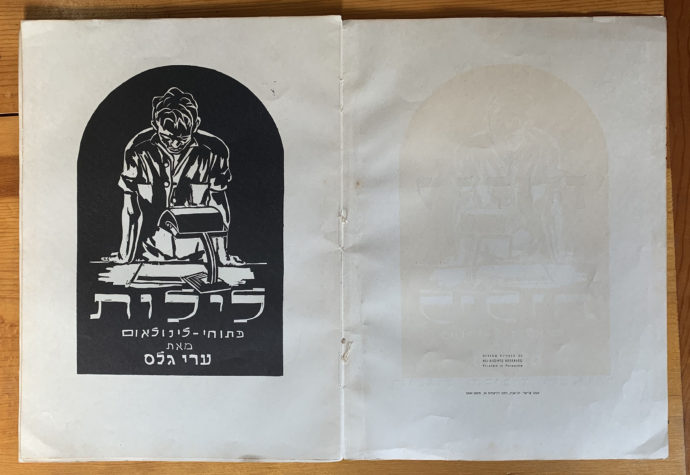

The frontispiece of “Leilot,” artist Erich Glas depicts himself studying his work. The book measures 13 1/8″ x 9 1/2″ (33.3 cm x 24.2 cm).

Intact Leilot

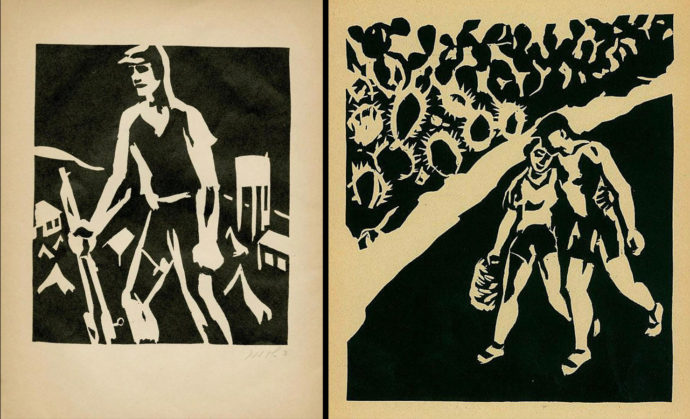

While my portfolio version of Leilot was complete, I jumped at the opportunity to own a copy as originally published. How any copies stayed intact is a wonder. If you look carefully on the fold between these pages, you’ll see that it was bound with thin string. I know little about the publishing industry in Eretz Israel (pre-Israel Palestine), but Leilot‘s binding was not an exception. Hoenich’s The Road of Suffering was bound the same way.

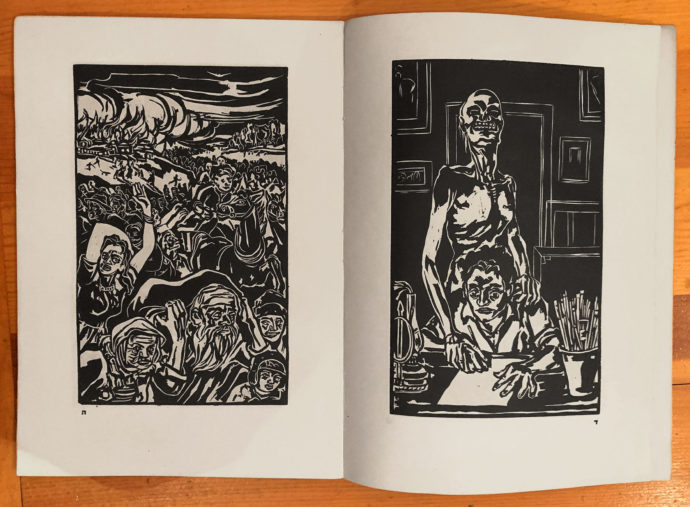

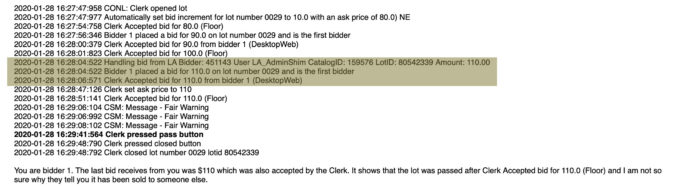

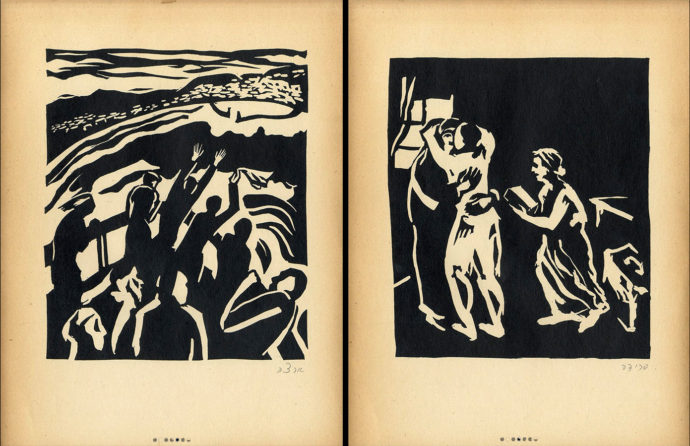

“The Storm” (right) and “Contemplation” (left) are the second and third images of “Leilot.” They depict the artist’s nightmare that was catalyst for the book’s creation.

One thing the bound Leilot forces you to do is acknowledge that Hebrew is read right to left. So you need to open the book on the left and turn the pages from the left, but you read the contents (in this case, the images) from right to left.

The next pair of images begins with “Death Speaks” (right), showing the artist being directed to make his linocut narrative, which starts (left) with “Refugees,” showing Jews fleeing their village in flames.

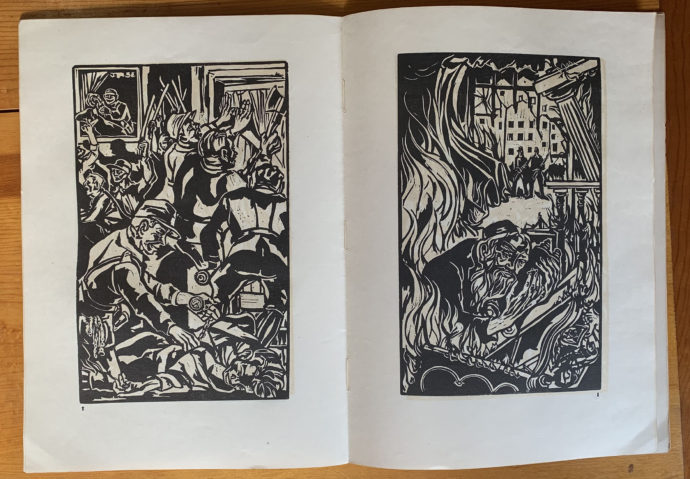

The next pair of images–”In the Flames”(right) and “Pogrom” (left)–puts the focus on Germany and Krystallnacht (Night of the Broken Glass), the 9-10 November 1938 pillage by stormtroopers and civilians throughout Nazi Germany.

The the entire sequence can be viewed by clicking on this link to a PDF. Shown with each image is its title, as translated from the image list. (The vertical image list is visible in the photo from the unbound copy shown in the Introduction to this post.)

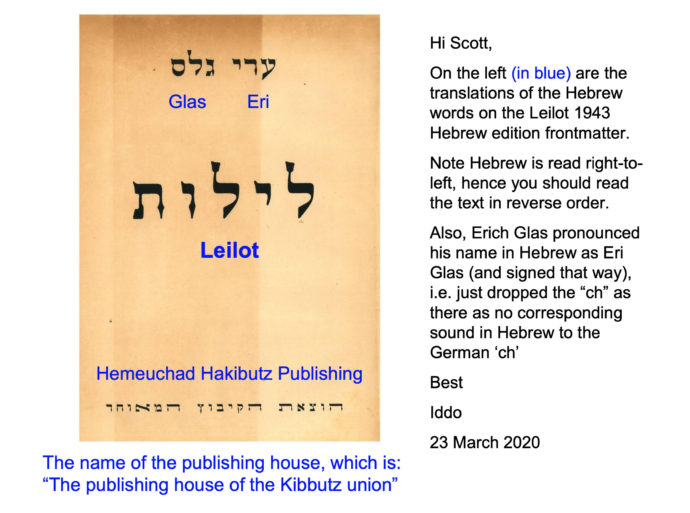

Throughout my blogging about Glas’s Leilot I kept referring to the medium as linocut (linoleum cuts) because that is what his grandchildren said they were. Then just this March (2020) I asked Iddo Gal, a grandson, to translate the few words in Hebrew that appear on the cover or inside the book.

In an email Gal wrote: “The publisher was Hakibutz Hameuchad, the official publishing arm of the Kibbutz union (organization) to which Yagur [the kibbutz that Erich Glas joined] belonged. There were 3 or 4 such unions of Kibbutzim at the time (each had a different political affiliation). I think Hakibutz Hameuchad had more than 100 Kibbutzim as its members and worked jointly on their behalf.”

As to the small text opposite the frontispiece, Gal noted: “In my Hebrew version of Leilot, it says the printing house was ‘Arieli print,’ located at Lilienblum Street #34 in Tel-Aviv, phone number #5349 (yes, a 4-digit number–they didn’t have many lines in those days in Tel-Aviv).”

Note Glas’s Hebrew signature and the 1942 date on the frontispiece, as depicted on the second of Gal’s PFDs. Leilot was first printed in 1943 in South Africa in English, then published in Palestine in 1945 in Hebrew. The frontispiece, however, was the same for both editions.

In the 1945 edition, there are a few lines in Hebrew opposite the last linocut. Iddo remarked on those words as well: “And to cover the end-matter as well, let me note that on the very last inside page, there is a small text in Hebrew at the bottom, saying, ‘A special edition of this book, with an introduction by Eric Rosenthal, was published by Antonos Publishers in Johannesburg (South Africa).’ No date is given there.”

The South Africa (SA) edition was limited to 200 copies numbered and signed by the artist. At my request, Hagar Lev checked with the Bar-David Museum of Art and Judaica in Kibbutz Baram, which had a copy of the SA edition. She reported back that plates in the SA edition were printed on one side of the page. This was pretty much expected in signed limited edition where the images most likely were printed from the linoleum blocks. But it then raises the question: What about the Hebrew edition that was not signed by the artist and where the plates were printed on both sides of the page? Were those images printed from the block?

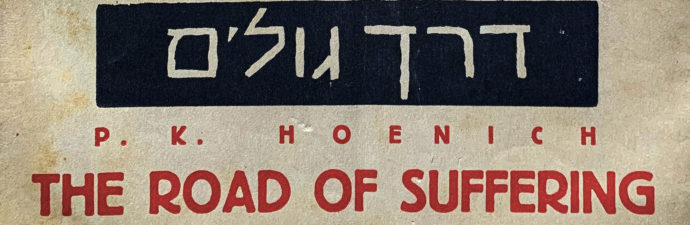

P.K. Hoenich’s book measures 9″ x 8 5/8″ ( 23.1 cm x 22.9 cm) The pages of this book, which is bound with string like “Leilot,” are actually quite tan. My iPhone insists on lightening the paper.

The road of suffering

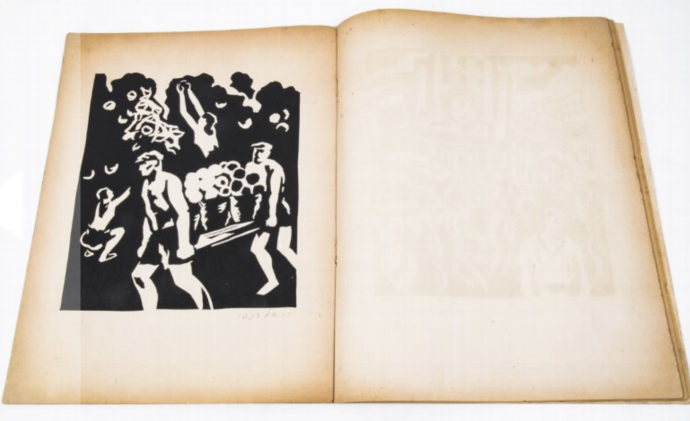

My purchase of the intact copy of Leilot from J-B involved buying a second wordless narrative of relief prints. This was Paul Konrad (P.K.) Hoenich’s 1943 The Road of Suffering. The colophon states: “This edition was printed from the original blocks.” Hoenick signed it both in Hebrew and in English. No edition size was given.

The Israel Museum in Jerusalem has a brief bio of the artist on its website. (link)

Paul K. Hoenich, Israeli, born in Austria, 1907-1997

Paul Konrad Hoenich was born in Czernowitz, Austria (today Ukraine). In 1925-1928, he studied art in Vienna, Florence and Paris. In 1929, he served in the Rumanian army. In 1930-1935, he lived in Bucharest, Rumania, where he worked as a teacher and artist. In 1933, he represented Rumania in an international exhibition of etchings in Poland.

In 1935, he immigrated to Palestine with his wife and settled in Haifa. In 1936, he established a local art school. In 1950, he began to lecture at the Technion in Haifa. He taught two-dimensional design in the Faculty of Architecture.

The book “Fifty Artists” (Chagall’s House–Haifa, Massadah Publishing House Ldt, Tel Aviv, 1955), for which Hoenich served on the editing committee, adds the following about his career: “He has exhibited his works in many exhibitions including the Palestine Pavilion at the World Fair in New York in 1939, the International Art Center in London in 1946 and has had a one-man exhibition in 1951 at the Palace if Fine Arts in Brussels.”

Returning to the Hoenich bio at the Israel Museum website:

In 1966, he was appointed an associate professor by the Technion and researched various topics related to paint and color. In the 1960s, his study of art and automatic technology (Robot-Art) was published in various journals. [The full title was Robot-Art: Research No. AR 10 of the Faculty of Architecture. As of 25 March 2020, three copies were listed on Ababooks.com]

Hoenich’s paintings and etchings are expressionist in style. His “Derech Golim” series (1943), for example, consists of 13 expressionist etchings on topics related to Jewish history. [This is referring to The Road of Suffering, which actually has woodcuts, not etchings.] In the 1970s, inspired by his work at the Technion, he created several avant-garde kinetic works that make use of light rays. In the 1980s, he went back to traditional painting.

In 2002, the Technion established a gallery for experimental art named after him. According to artfacts.com, the “Paul Konrad Hoenich Gallery of Experimental Art and Architecture is located at the center of the Technion’s Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning in Haifa…. The Gallery stages exhibitions on various chapters in the history of architecture and art in Israel and at the same time offers premier exposure to new and innovative works and projects…. Donated by P.K. Hoenich’s widow, Ruth Hoenich, the Gallery serves as a place for the safe keeping and promotion of Hoenich’s artistic and educational heritage.”

After reading the first draft of this post, Iddo Gal made an important point, one that I as a non-Hebrew reader did not recognize.

A note about Hoenich’s title The Road of Suffering. The Hebrew words in the title are Derech Golim, which translate to The Road of Exiles…. But he chose for the English title not this direct literal translation, but a different word (“suffering” instead of “exiles”) which directly points to the *consequence* [his italics] of being an exile, as Jews have been through the ages. Perhaps Hoenich wanted to make doubly sure that those who read English fully understand what exiles go through?

The above point may be of some interest simply because it speaks to how the artist thinks of what goes through the mind of the viewer/spectator. They [Glas and Hoenich] both used so few words in their work, so every word counts.

Is Hoenich saying, I wonder, being in exile is synonymous with suffering? Or by extension, in order for Jews not to suffer they need to live in Eretz Israel, the land that would, in part, become Israel.

As part of the Jewish diaspora in America that a generation ago enlisted to destroy the Third Reich–my father fought in Europe in WWII and was a POW for 22 months–and then after the war rallied around the new state of Israel, I can safely say that Jews living around the world have been an essential hedge against extermination.

Like in the presentation of “Leilot,” the pairings of plates in Hoenich’s book should be read right to left.

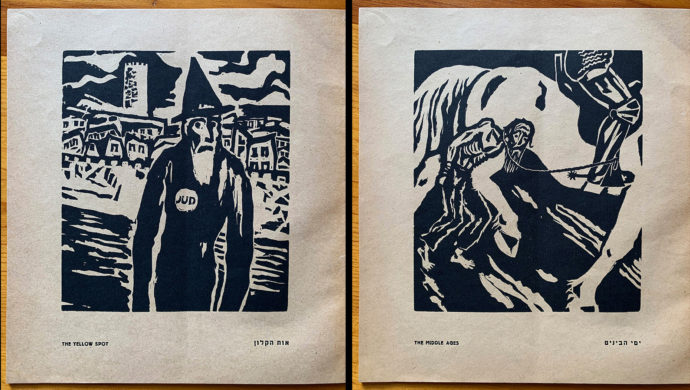

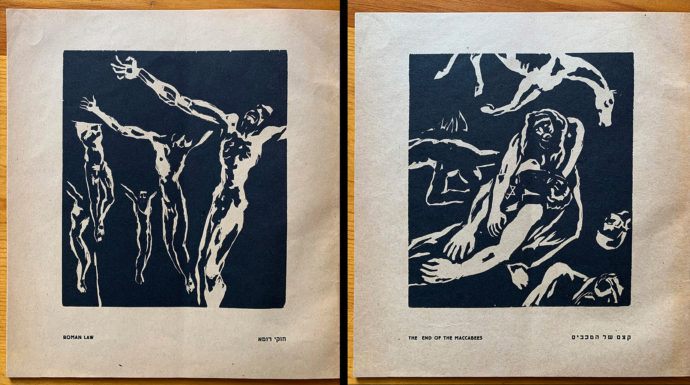

Hoenich presents The Road to Suffering chronologically. The first woodcut begins with “The End of the Maccabees,” which refers to the 63 BCE Roman conquering of Judea, the Jewish kingdom that began with the Maccabees’ successful rebellion in 167 BCE against the Seleucid Empire. Then “Roman Law” stresses the fact that Jesus was hardly the only Jew to be crucified.

The armored leg of the knight places the next scene squarely in “The Middle Ages,” while “The Yellow Spot” and the next few images describe the horrors facing Jews before the rise of Hitler.

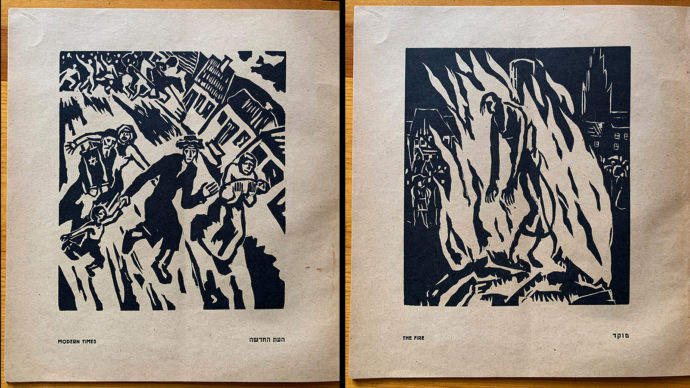

The title “Modern Times” is, in a sad way, a kind of a joke because the scene of Jews fleeing with a torah has happened “Most Times.”

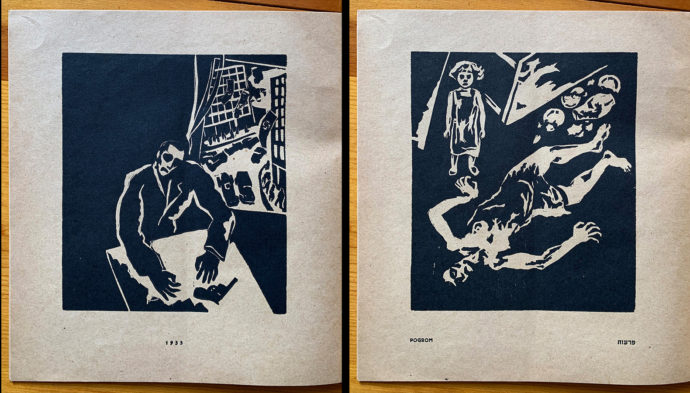

The term “Pogrom” arose to give a name to the periodic raiding of Jewish villages and subsequent slaughter that took place in the Russian Empire. Then with Hitler’s rise in Germany in “1933” Nazis would soon take the horrors of a pogrom to unprecedented levels of inhumanity.

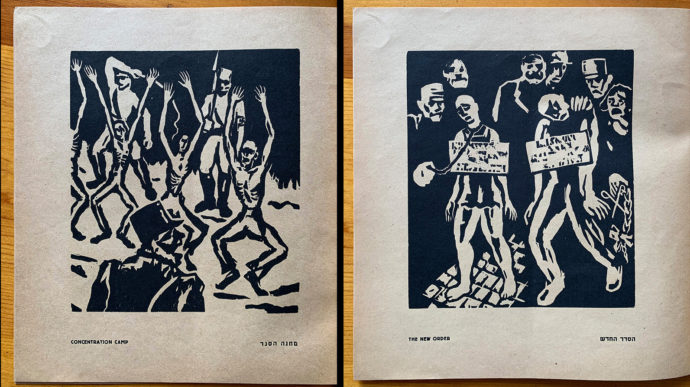

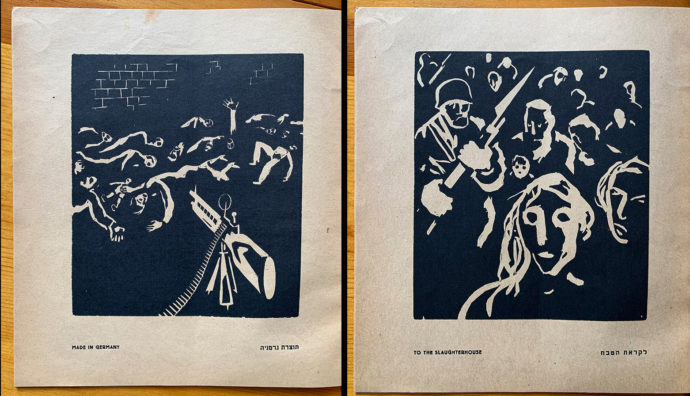

I’m afraid the savagery of the Third Reich needs no enumeration by me, but remember that Hoenich’s book came out in 1943, when there was a certain amount of denial of these atrocities in Eretz Israel.

Perhaps the most pungent caption is the one for the left image: “Made in Germany.”

Hoenich ends with a question mark: Is escape by boat to Eretz Israel “The End” of suffering?

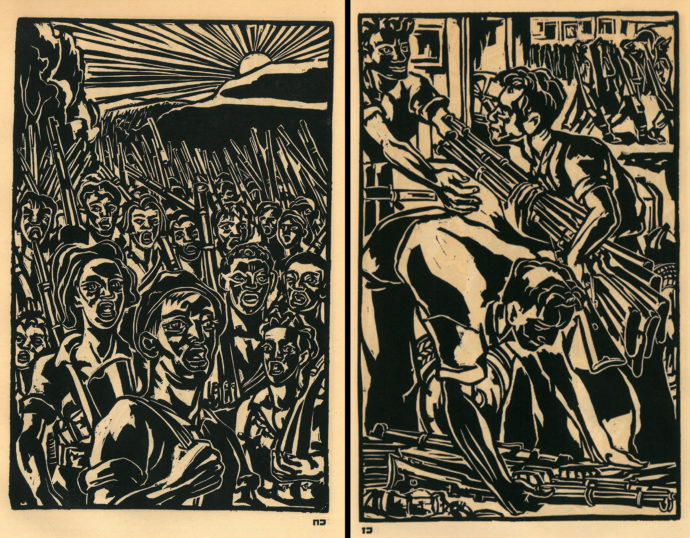

Erich Glas also has a plate with refugees on a boat, but he then had an image of drowning. His last two plates (above) in a way are an answer to Hoenich’s “The End?” In order to achieve an end to suffering, Glas says Jews–men and women–must arm themselves.

(The back cover of the Hoenich book says “N Warhaftig, Haifa” did the printing. I asked Iddo Gal about it. He responded: “I looked up the name ‘Warhaftig’ (in Hebrew it can also be ‘Varhaftig’) and found several entries. The info indicates it was established in 1925 in Haifa, became the main/leading print house in Haifa, received many print jobs from the British system during the Mandate period (pre-1948) and from academic institutions, government and businesses. It existed for 50 years until it was bought by its employees in 1970. It’s now called Ofek printers.”)

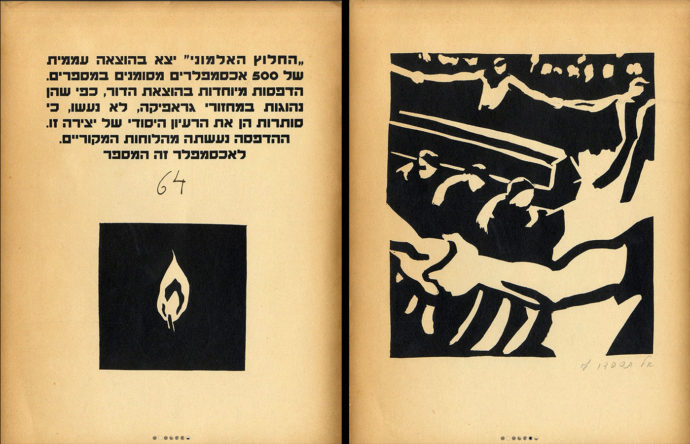

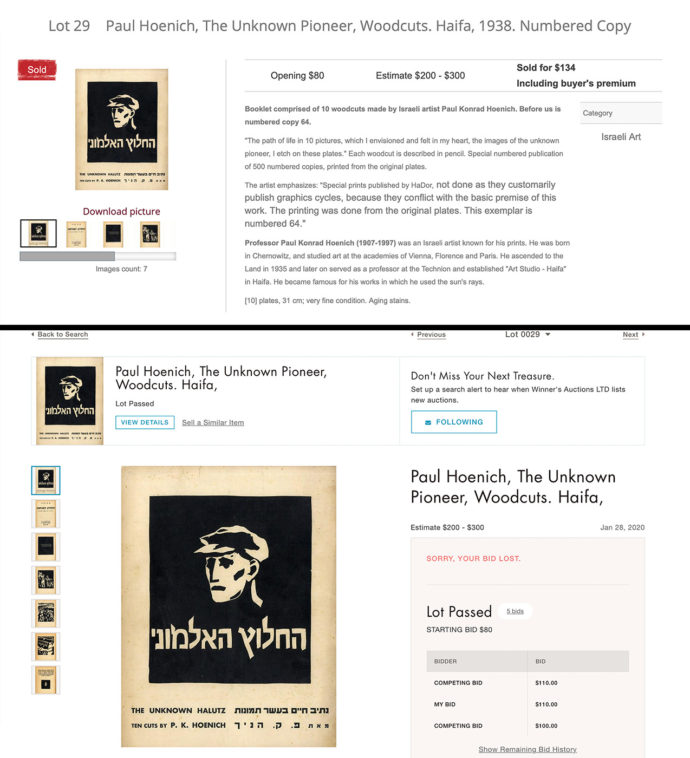

almost another hoenich

As I was negotiating with the J-B for the purchase of the intact Leilot and The Road of Suffering in January 2020, another P.K. Hoenich book of woodcuts–The Unknown Halutz–came up at Winner’s Auctions in Jerusalem. Using the LiveAuctioners.com website, I was approved to bid. It opened at $80. I bid $90. Competition bid $100. I bid $110. There were no other bids. But just as I was expecting to see that I won the lot, the item was marked “passed.” I was totally peeved. Here are two records of the same sale. The top record was what happened according to Winner’s Auctions. Hoenich’s The Unknown Halutz sold for $134 including buyer’s premium ($110 hammer price plus 22% buyer’s premium of $24). The bottom record is from the LiveAuctioners website. It recorded that the lot passed, i.e. was not sold.

Here are two records of the same sale. The top record was what happened according to Winner’s Auctions. Hoenich’s The Unknown Halutz sold for $134 including buyer’s premium ($110 hammer price plus 22% buyer’s premium of $24). The bottom record is from the LiveAuctioners website. It recorded that the lot passed, i.e. was not sold.

Confused to say the least, I contacted Winner’s and asked why I wasn’t the winning bidder. The answer: “The 2 bids came in on the same time and the bid on Bidspirit was accepted first! Sorry, sold.” I replied: “Very unorthodox! You should have posted the Bidspirit bid so I could compete against it.” The Winner’s response: “We have a few platforms simultaneously and sometimes there are technical hitches… If you want a certain item very much you need to register via Bidspirit and you can then ask for a live call during auction.” Bidspirit is another auction bidding site that according to its website: “Today, Bidspirit is used by most auction houses in Israel.” So I guess Winner’s gave preference to the Bidspirit bidder for the Hoenich.

So I turned to LiveAuctioneers for an explanation of what happened. A clerk there sent me the bidding history (above). I highlighted the simultaneous bids for $110. The Winner’s clerk accepted the bid from “bidder 1,” which LiveAuctioneers (in the sentence below the bid history) identifies as me. But then the Winner’s clerk accepted the other bid.

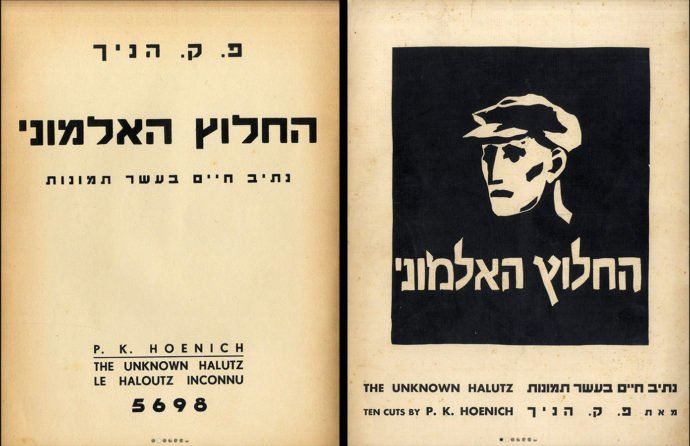

Despite having lost the lot under curious conditions, the auction listing did provide me with images of Hoenich’s The Unknown Halutz .

Once again the pages of this book are presented right (the cover) to left (title page). (Images from the Winner’s Auctions listing)

As stated in the Israel Museum bio of Paul Konrad Hoenich, the artist and his wife emigrated from Rumania in 1935 to settle with his wife in Haifa, Palestine. The Unknown Haltuz (Pioneer) was printed in 1935. In 10 woodcuts, it attempts to illustrate life in the fledging Jewish homeland from arrival to burial.

Another copy of this book was offered by Dynasty auction in Jerusalem in October, 2019. (It passed.) But the listing on LiveAuctiuoneers gives title to the 10 plates:

Another copy of this book was offered by Dynasty auction in Jerusalem in October, 2019. (It passed.) But the listing on LiveAuctiuoneers gives title to the 10 plates:

The tables describe the various stages of the “Halutz” who comes to Israel to becoming an employee pioneer: farewell, on the ship, to our land, craft, from the town, to the village, partner, grove, guard, do not eulogize me.

I’m guessing as to the sequence, but I suspect the first plate is the one on the right “Farewell.” And the second plate (on the left) is “On the Ship.”

The plate on the right could either be “From the Town,” “To the Village” or even “Partner.” The one on the right must be “Guard.”

Another auction site (antiques.co.uk) had an additional listing for Halutz, this time from October, 2018. It provided this image of the plate that I presume is “Grove.”

Returning to the Winner’s listing, the plate (on the right) is “Do Not Eulogize Me.” Finally here is the colophon.

Once again I turned to Iddo Gal, one of Erich Glas’s grandchildren, for a translation of the colophon.

In comparing the images in the two Hoenich books–Halutz in 1938 and Suffering in 1942–the cutting of the blocks is less harsh in the former (with more curves and fleshed-out bodies) than the jagged, brutal cuts that make up the images the latter. The hope and promise he sought to express in Halutz was replaced by the anguish and anger repeatedly cut into Suffering.

One to Come

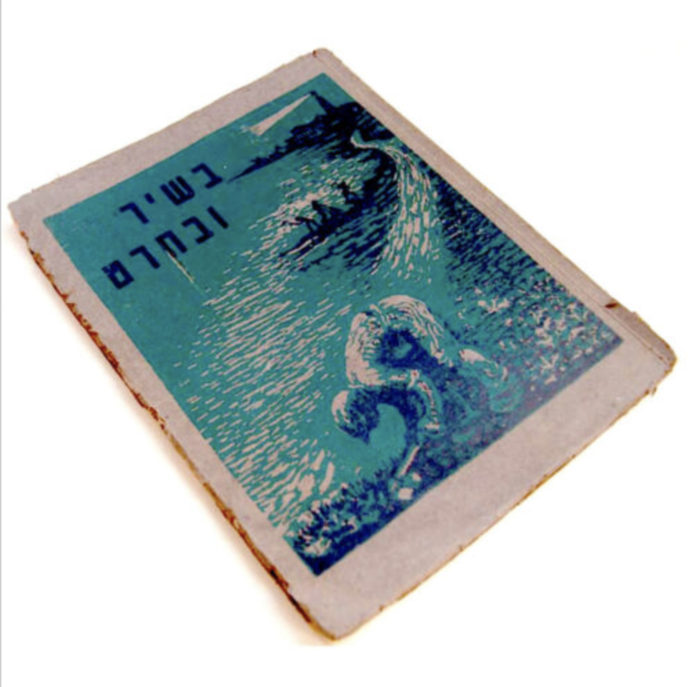

Once again J-B came up with another book with relief prints done in Eretz Israel. Here is part of the eBay listing with his characteristic overuse of CAPITAL LETTERS:

The poetic ART ANTHOLOGY named “BESHIR UBECHERET” (“With SONG and with ENGRAVING SCULP”), An anthology of POLITICAL-SOCIALIST-ZIONIST POEMS by kibbutz members which was published in 1939 by the Kibbutzim of “HASHOMER HATZAIR” was accompanied by around TWENTY ORIGINAL LINOCUTS, Printed on separate paper sheets; Originally bound with the book, FIVE Linocuts were made by the Kibbutz born Israeli artist YOHANAN SIMON, a member of OFAKIM HADASHIM ( NEW HORIZONS ) art movement . A strong influence of FRANS MASEREEL is evident in many of the linocuts. The pieces, Dedicated to ” WORK, LABOUR, REDEEM of LAND and DEFENSE” Depict TYPICAL sceneries of Kibbutz members working in the KIBBUTZ FIELDS etc.

When this item arrives from Israel (most likely delayed by the caution due to the covid-19 pandemic), I’ll create a new ART I SEE post.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/eretz-israel-narratives-in-relief-prints/trackback/