Elbridge Kingsley and Gifts for a Blogger: More on 19th-Century Wood Engravings

Introduction

Surprises even happen in the obscure world of blogging on late 19th-century American wood engraving. In July, 2013, I wrote about what I learned from reading William H. Brandt’s book Interpretive Wood -Engraving (2009, Oak Knoll Press, New Castle, DE). See: http://www.scottponemone.com/new-school-wood-engravers-forgotton-19th-century-celebrities/ And then I posted an interview I did with Bill Brandt: http://www.scottponemone.com/interpretive-wood-engraving-interview-with-its-author/ Bill then made some suggested corrections, and in his next email said: “And in general, your doing these blogs so very well has pleased me greatly and I hope will incite interest in SAWE.” [Society of American Wood-Engravers] Then he added: “The other thing I probably should mention is that I have several hundred signed proofs of seven or eight images by Juengling, Closson, Miller, Teel and Fillebrown. These were no doubt originally printed for inclusion in a fancy edition of [Silvester R.] Koehler’s [1886] book American Art.” Well, I suspected that last sentence was an invitation for me to make an inquiry about whether he would offer to sell me any of his duplicates. So I asked him how much he would charge? Instead of pricing them, he wrote: “Seven of the eight wood engravings I mentioned will be on their way to you after I get your mailing address. I did not include the engraving by [George A.] Teel because there was only one of them. In the set I made up for you, there are four by Frederick Juengling, and one each by Willy Miller, George Closson and Francis Fillebrown. They are my gift to you for all the work you have done on the blogs. I hope they will be useful in your work with students.”

I was quite flattered, but when his package arrived, I was quite confused. Instead of the seven pencil-signed Japan-paper proofs, there were nine. The extra two were duplicates of two of the four different Juenglings. So I emailed Bill to say I would send them back. But he responded: “I’m embarrassed. The other two Juenglings are still lying on the cabinets. I’ll send them. You needn’t return the duplicates. Just sell them or use them for trading or give them to someone whose appreciation for wood engravings will be increased. You didn’t mention the condition the prints arrived in. I trust they were ok.” I tried to explain that I had all four different Juengling prints, but that message evidently didn’t register. So with his second package I had now duplicates of each of the four Juengling prints. At that point I decided that further explanation would only add to the confusion. The duplicates would make nice gifts to print instructors who brought classes to view prints at my house. To date I’ve given two away. I’m sure they’ve found good homes. A gallery of the seven different proofs will be attached at the end of this post.

The second post-blogging surprise was an email from the great great granddaughter of one of the eminent 19th-century American wood engravers: Elbridge Kingley (1842-1918). This is what transpired:

Elbridge Kingsley gets a one-person show

In an email dated Sept. 12, 2013, Beth Vienot wrote:

I thought you might be interested in knowing about an upcoming exhibition on Elbridge Kingsley at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, in the Art History Gallery. It is being curated by Elizabeth Powell-Siercks for her Masters degree. There will be 24 prints, some photographs from his original glass plates and several of his wood blocks. The show runs October 24 – November 14.

My name is Beth Vienot, and Kingsley was my great great grandfather.

I stumbled on your site yesterday and was delighted to read your blogs on the Wood Engravers. I am starting to educate myself on the history and found your essays very helpful. They were nicely written and concise in explaining the distinctions and schism between the new and old school.

I especially enjoyed your interview with Mr. Brandt; it was a treat to read.

Also, the print that you feature by Kingsley, In the Harbor is being used as the poster or the announcement for the exhibition.

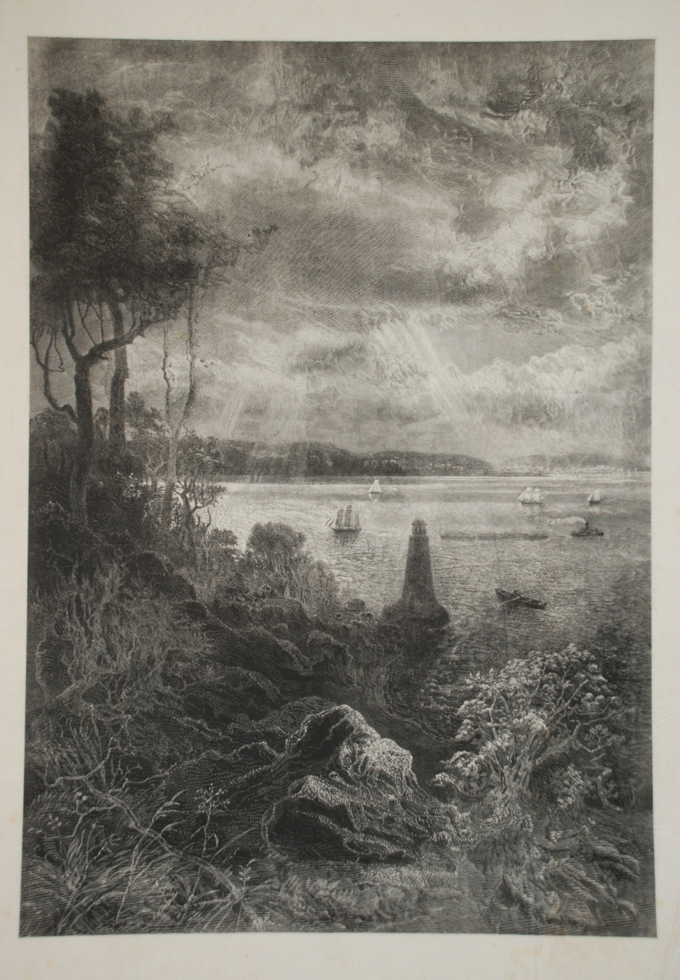

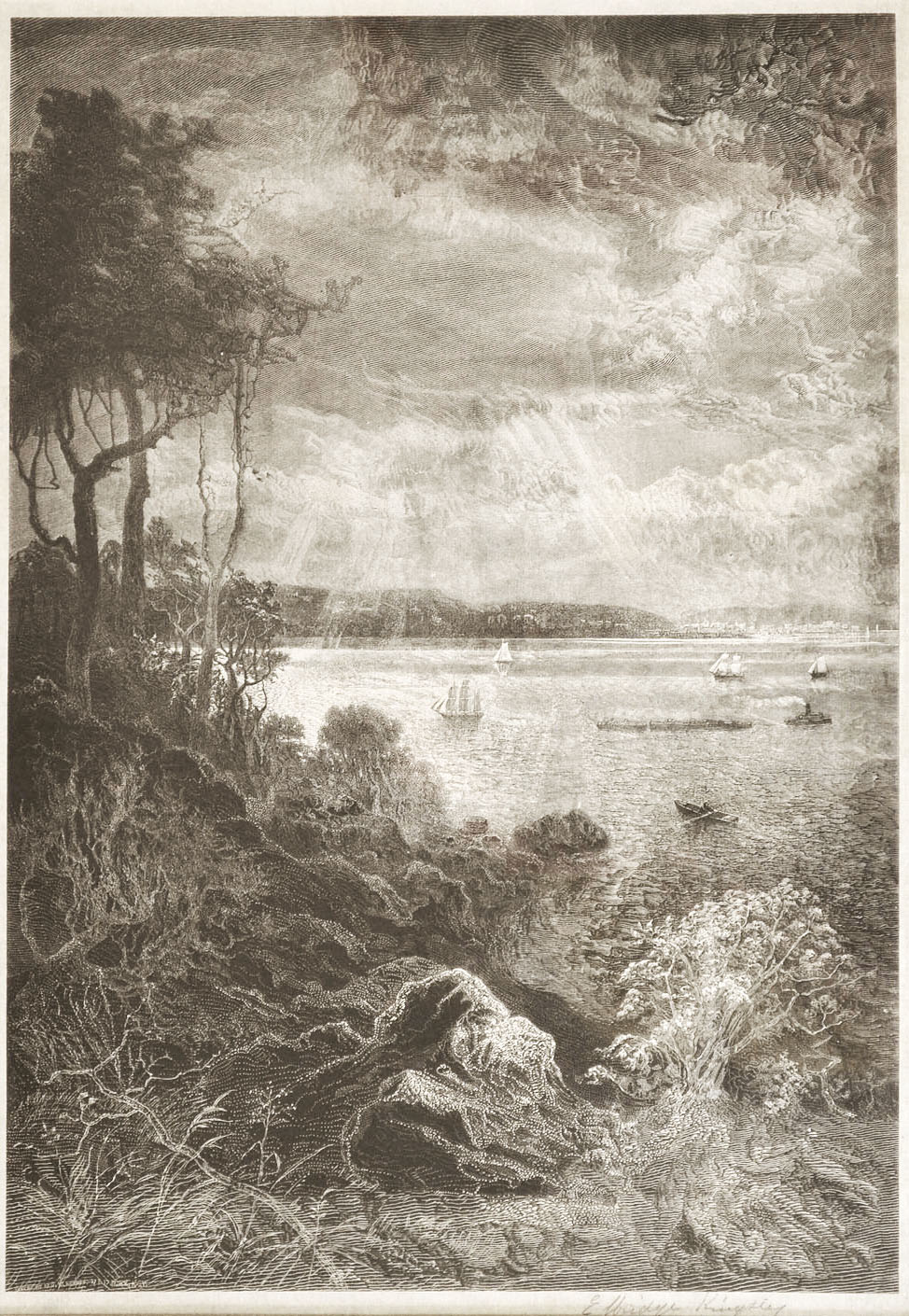

Beth sent me the exhibition postcard, but it’s too dark to reprint here. Instead, once again, here’s my copy of Kingsley’s In the Harbor:

In her next email, Beth confirmed that “most of the items in the show will be from our family collection of Kingsley’s estate.” (In her exhibition catalog, Elizabeth Powell-Siercks thanks Beth for lending her father Perry G. Vienot’s collection of Kinglsey items.) Then Beth throws another surprise: “Of interest, I have also attached a picture of In the Harbor. We have several of these on japan paper but only this one with the lighthouse. As a visual person myself, to see another artists work, reworked or corrected, is a not so common opportunity/invitation to understand the artists visual problem solving. Kind of amusing I think.”

In the Harbor, c. 1889, wood engraving, 16 7/8″ x 11 7/8.” The Perry G Vienot Collection.

A lighthouse??? Once I saw Kingsley’s lighthouse version of In the Harbor, I checked out my print, and sure enough you can plainly see where the lighthouse had been removed:

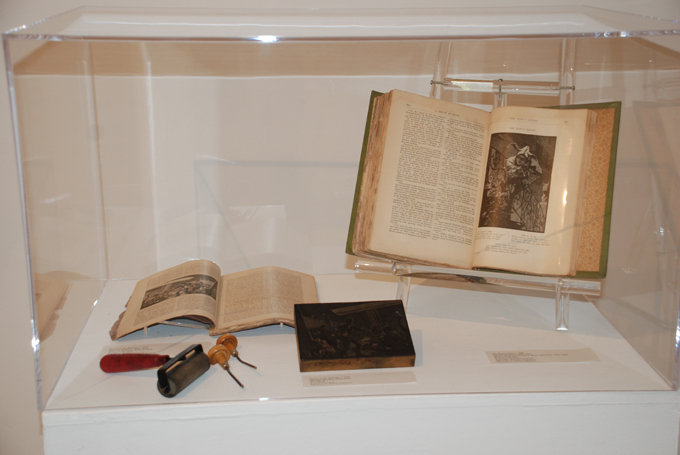

Once I returned from my month’s artist residency in Key West (that’s certainly another story), I asked Beth to send me photos of the exhibition installation. Most of the images were not usable here, but here are two. The first shows some wood engraving tools and an original Kingsley engraved block (I believe for the illustration for the book on the left).

These objects and photographs are from the Perry G. Vienot Collection.

The photographs on the left are quite curious. They show the wagon Kingsley had built. In her exhibition catalog, Elizabeth says, “Fellow engraver Frank French (1850-1933) credited Kingsley with the invention of the ‘camping car,’ with its ‘snug and well-contrived accommodations for painting and wood engraving.’ ” Kingsley’s horse-drawn “gypsy” wagon enabled the artist to produce landscapes in situ. Elizabeth writes that he would engrave directly onto the block, or first draw on the block, or work from his own photographs.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. In her words let Elizabeth explain how her Kingsley exhibition came about:

I learned of Mr. Kingsley during a graduate colloquium on American prints (1840-1940) at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The professor teaching the course, Linda Brazeau, owns a Kingsley print and is friends with the Vienots. For the colloquium the class put up a show of prints by several artists spanning a century of American printmaking (etching and engraving). Though for the class exhibition I wrote about images of the West (by Remington, Bodmer and Farny), I was very impressed with Mr. Kingsley’s technical skill and the quietude of his landscapes. Graduate students at our university have the option of a thesis paper or a thesis exhibition. Those looking to enter PhD programs usually do thesis papers while those seeking museum work after graduation tend to do graduate exhibitions. Linda put me in touch with the Vienots, and eventually we went to see their collection.

After seeing the collection I would say the process took about a year and a half from start to finish. It took over a year of research, mostly due to the antique nature of the sources, but my thesis proposal was approved. Then I designed the press materials, planned and installed the exhibition, and wrote the catalog over a period of many months.

I was especially grateful to the Library of Congress’s “American Memory” website where researchers and nineteenth century enthusiasts can find popular periodicals. Each page is scanned exactly as published and searchable by key word.

In her catalog Elizabeth focused, in her words, “on Kingsley’s place in the greater spectrum of American landscape tradition.” She wrote that Kingsley was more influenced by the French Barbizon School painters–many of whom worked outdoors–than by the American Hudson River landscape painters. “Kingsley’s plein air work,” she wrote, “may have been inspired by these [Barbizon] artists.” Like his fellow late 19th-century American wood engravers, Kingsley began his career reproducing paintings by other artists for books or periodicals, but his most celebrated works, according to Elizabeth, were his original compositions. Yet his original works were influenced by his reproductive work. Below are wood engravings by Kingsley of paintings by George Inness and Albert Pinkham Ryder, artists whom Kingsley had befriended.

Kingsley exhibition catalog by Elizabeith Powell-Siercks

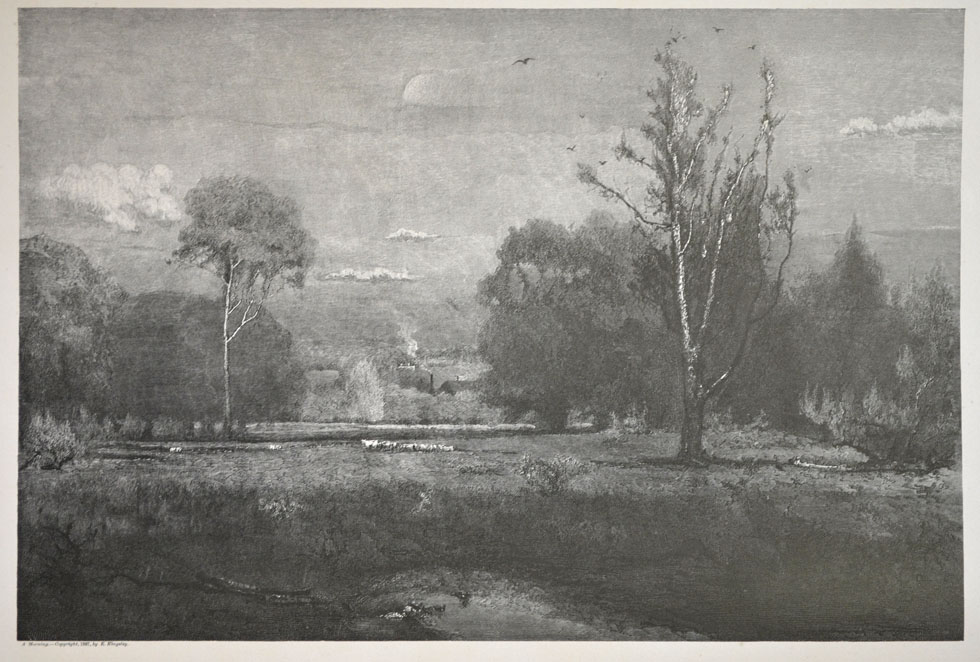

A Morning, 8″ x 11 3/4″, from a painting by George Inness, and (below the Inness) The Flying Dutchman, 8 5/8″ x 10 3/8″, from a painting by Albert Pinkham Ryder. Both were published in Engravings on Wood by the Society of American Wood-Engravers (the source for these images).

Here’s an original Kingsley composition that Elizabeth says mirrors Ryder’s allegorical paintings and Ryder’s interests in “Richard Wagner (1813-1883), Norse and Greek mythology, and Christian iconography.” It’s entitled The Celestial City. It seems to have more than a dash of American painter Thomas Cole (1801-1848) and the English painter and engraver John Martin (1789-1854).

The Celestial City, c. 1884, wood engraving, 7″ x 4 3/4.” The Perry G Vienot Collection.

Elizabeth writes that Kingsley’s The Sunset is his most Inness-like wood engraving. (Unfortunately I don’t have at the moment a good image of this print to show here.) Nonetheless, Elizabeth says Kingsley enjoyed “an enduring relationshop” with Inness and “replicated many Inness paintings throughout the 1880s and 1890s. However, here’s one of Kingsley’s original wood engravings as reproduced in Bill Brandt’s Interpretive Wood-Engraving:

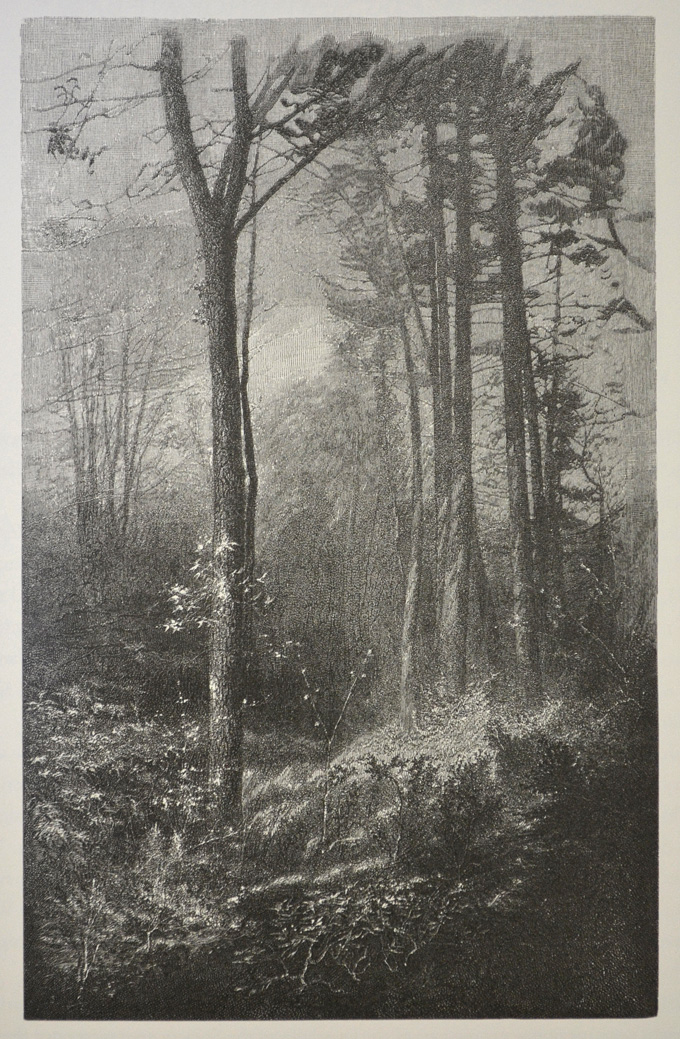

View in New England Woods, 1882, wood engraving, 8″ x 5″

Forest at Fountainbleu, after Corot, wood engraving, 3 1/2″ x 5 3/8″. The Perry G. Vienot Collection.

“Kingsley was especially adept at translating the muted browns and greens of the work of the Barbizon artists. …,” Elizabeth writes. “When replicating Corot’s Forest at Fountainbleu, a painting which is over four by three feet, Kinglsey retained all the finer texture and translated in black and white the uniform color of the work.” Kingsley’s original compositions, she says, “invite the viewer into patches of forest and woods, much like Barbizon landscapes.” In summary, Elizabeth states, “Kingsley was certainly aware of Hudson River School artists like Thomas Cole and his student Frederick Church, who viewers are placed omnipotently out and above sublime scenes of nature; Kingsley preferred the Barbizon method of an intimate view of nature.” In short, she writes, “Kingsley’s work is as much a product of the contemporary art scene, as it is his own artistic inclinations.”

I, as a collector interested in the whole spectrum of wood engraving, am indebted to Elizabeth Powell-Siercks’s efforts to return light to the once-celebrated career of Elbridge Kingsley. A very impressive exhibition and catalog! And many thanks to Beth Vienot for alerting me to the exhibition and for being a very proud–justifyingly so–great great granddaughter of Elbridge Kingsley.

Bill Brandt’s Largesse

Following are the seven signed Japan proofs given to me by Bill after my posts on his book Interpretive Wood-Engraving and my interview with him.

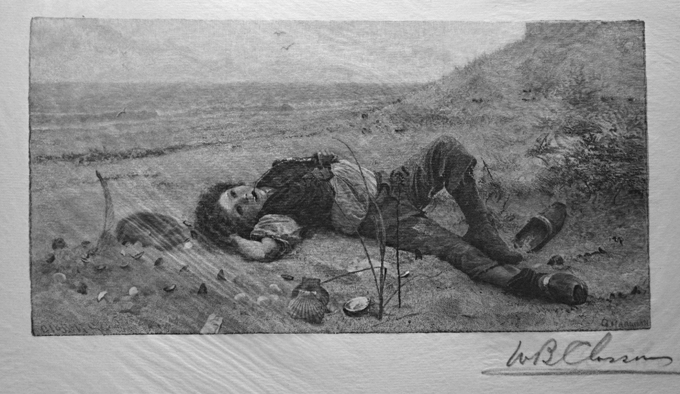

William B. Closson (American, 1848-1926), Castles in the Air, wood engraving, 1886, 4 3/8″ x 8 5/8″, from a painting by Alexander Harrison.

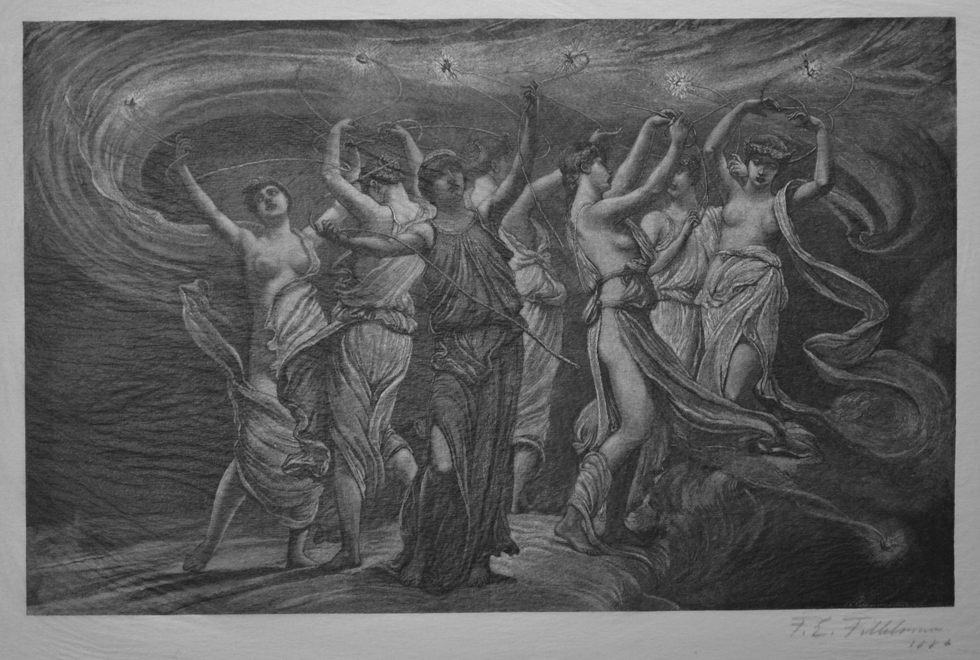

Francis E. Fillebrown (American, 1854-?), The Pleiades, wood engraving, 6 3/8″ x 10″, from a painting by Elihu Vedder.

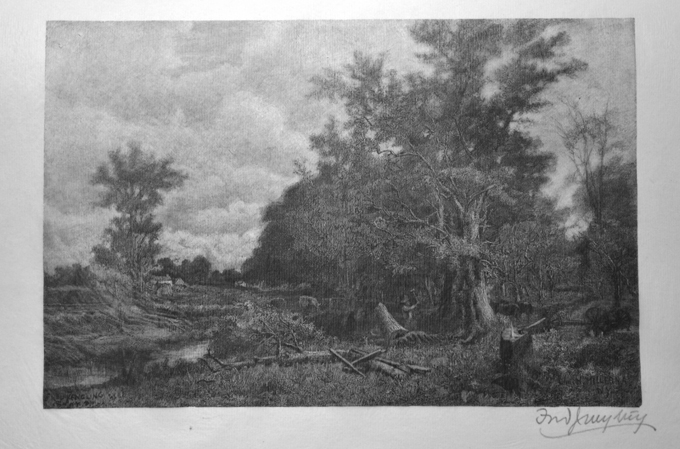

Frederick Juengling (American, 1846-1889), A Bouquet of Oaks, wood engraving, 5 3/4″ x 8 7/8″, from a painting by Charles A. Miller.

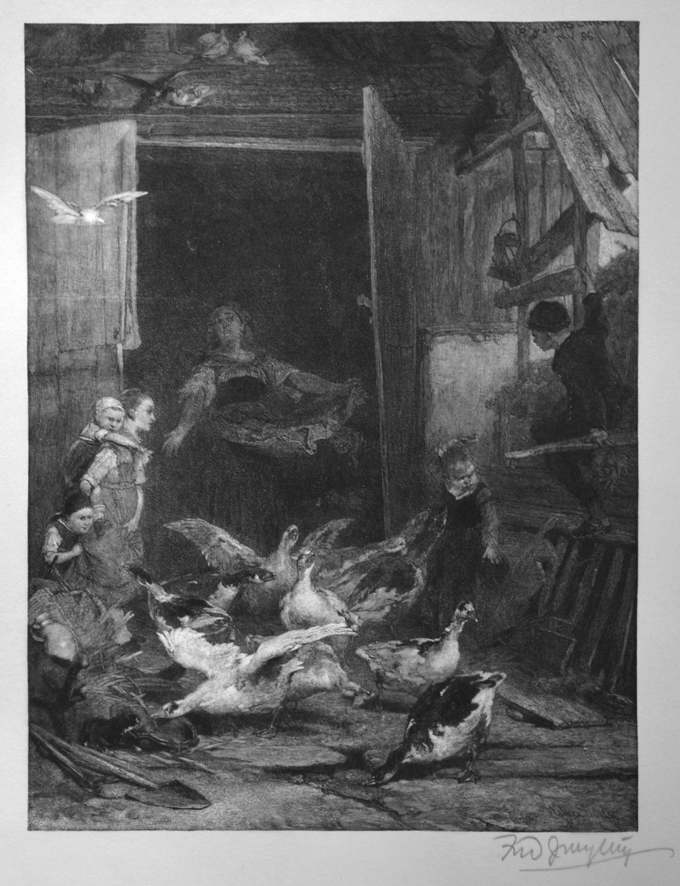

Juengling, Good Morning, wood engraving, 9 7/8″ x 7 3/8″, from a painting by Walter Shirlaw.

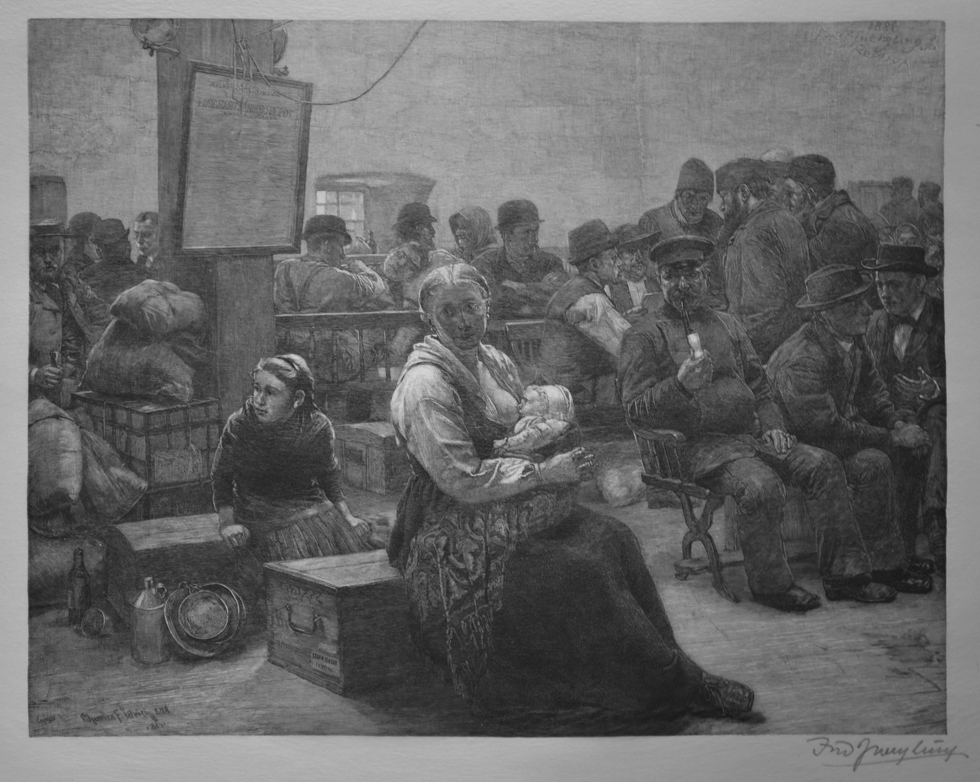

Juengling, In the Land of Promise, wood engraving, 8 3/4″ x 11″, from a painting by Chas. F. Ulrich.

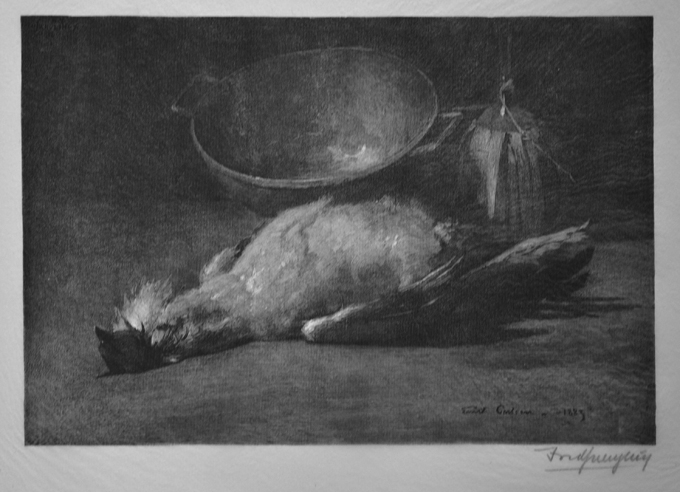

Juengling, Still Life, wood engraving, 5 1/2″ x 8″, from a painting by Emil Carlsen.

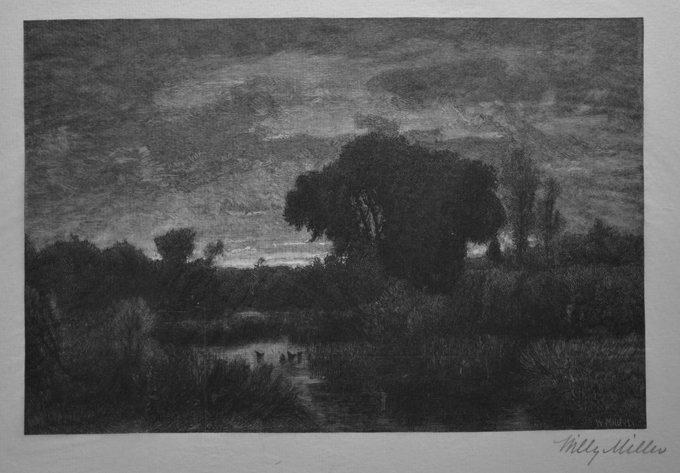

William R. Miller (American, 1850-1923), Sunset, wood engraving, 4 5/8″ x 7″, from a painting by George Inness.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/elbridge-kingsley-and-gifts-for-a-blogger-more-on-19th-century-wood-engravings/trackback/

Excellant article, Scott. Kingsley’s work is truly spectactular.

Enjoyed the article, Scott. The Pleiades and In the Land of Promise is my favorite.

Middle sis, quite a pleasure to hear from you. Never knew prints like these would interest you. I’m pleased

Hi Scott, What a fabulous blog. Thank you for the chance to see these early wood engravers whom I knew very little. Always interested in learning.

Keep it up.

Regards,

Lee

Lee, Always good to hear from fellows as fascinated by prints and printmakers as I am. Even 35 years into print collecting, I’m still on my learning curve too.