East-West Woodcuts: Urushibara & Brangwyn

INTRODUCTION

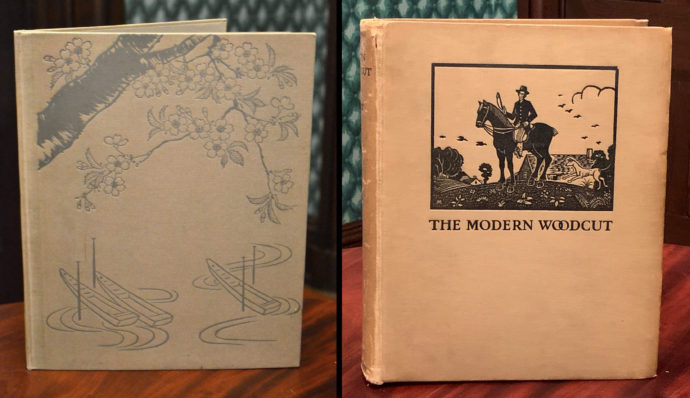

I think purchasing Ten Woodcuts by Yoshijiro Urushibara (Japanese, 1888-1953) last year from the Saru Gallery in The Netherlands was the culmination of a natural progression that began in the early 1980s with the purchase of The Modern Woodcut by Herbert Furst from Kelmscott Books in Baltimore. (Oddly enough both books were published in 1924 by John Lane, The Bodley Head Limited, London.) To help make sense of the progression you need to know the full title of Urushibara’s book, namely: Ten Woodcuts: Cut and Printed in Colour by Yoshijiro Urushibara after Designs by Frank Brangwyn, R.A. In short, you’ll find out that if it wasn’t for my interest in Brangwyn, I never would have sought out Urushibara’s book. Here’s how the progression worked out:

Frank Brangwyn

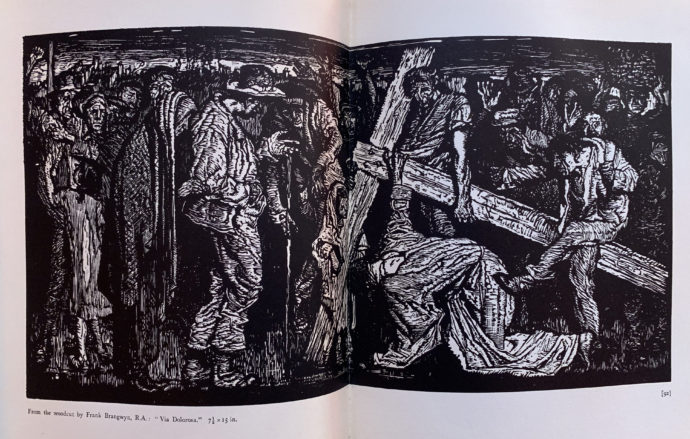

This two-page spread of the woodcut Via Dolorosa in Herbert Furst’s book The Modern Woodcut immediately put Frank Brangwyn (British, 1867-1956) on my collector’s radar. I loved the jittery light Brangwyn achieved with his gouging of the wood block. I also loved the theatrical staging of the figures, in that they run across the picture plane.

In his entry on Brangwyn, Furst wrote: “Amongst the foremost of living artists, and in certain respects perhaps the foremost, is Frank Brangwyn, who has taken up the woodcut only since the beginning of the great war, when a serious illness kept him from doing more physically strenuous work…. Brangwyn informs me that he did a considerable amount of wood engraving [Furst’s italics] in the orthodox manner in his early days, but I have no examples of it and so cannot judge its qualities. Certain it is that his later cutting has no relation whatever with orthodox work…. His style in his best and most characteristic cuts is a short nervous stabbing of the wood with the graver, almost analogous to the short stabbing touches of his brush on the huge canvases which carry his mural paintings. It is a style which is entirely his own. The design is in white line, roughly indicated, before the cutting, with chalk, but almost completely drawn in the cutting itself. His finest cut in this style is the “Via Dolorosa”….

To help describe who was Frank Brangwyn, I’ll turn to the introduction in Frank Brangwyn, a brief 2008 catalogue of his etchings by the Goldmark Gallery in Uppingham, Rutland, England. It began: “By the 1920s Frank Brangwyn was one of the best known British artists in the world. Born in Bruges, son of a Welsh mother and an English father, Brangwyn was apprenticed to William Morris (1882-4) and, like his master, became active in a variety of fields. Brangwyn was an independent artist, an experimenter and innovator, capable of working on both large and small scale projects, ranging from murals, oil paintings, watercolours, etchings, woodcuts and lithographs to designs for architecture, interiors, stained glass, furniture, carpets, ceramics and jewellery, as well as book illustrations, bookplates and commercial posters.”

Frank Brangwyn: A Mission to Decorate Life, a 131-page book, was published to accompany a 2006 exhibition at The Fine Art Society in London. Organized by the Liss Llwellyn gallery, all 300 artworks were for sale. (The book is viewable online at brangwyn.net courtesy of Liss Llewllyn.) Author Libby Horner wrote: “Brangwyn had no formal artistic education and remained throughout his life, at his own insistence, outside the art establishment. This was despite the fact that he was the recipient of endless honours…. Brangwyn’s lack of art education allowed him to flout convention, to experiment with techniques and mixed media….”

In the printmaking section Horner wrote: “Brangwyn believed fervently that art should be available to all, regardless of wealth or station, which explains his interest in all forms of printing. He designed well over 1,000 original prints, making him one of the most prolific printmakers of the 20th century, a remarkable feat considering that his prints account for less than tenth of his oeuvre.”

And as to his relief oeuvre, Horner wrote: “Brangwyn produced over 373 wood engravings and woodcuts between 1899 and 1935, including 71 bookplates and a large number of book illustrations and head and tail pieces.” She listed the 14 Stations of the Cross prints as his largest woodblocks. Via Dolorosa also known as Jesus Falls Below the Cross was 19.8 × 38.5 cm (7 7⁄8 × 15 1⁄8 in).

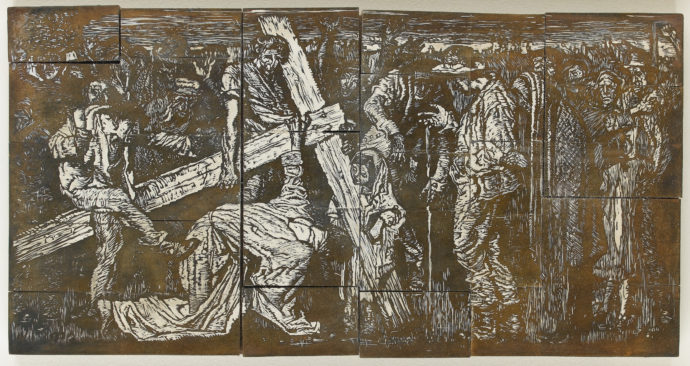

The woodblock for Via Dolorosa has survived and is for sale at Liss Llewellyn. The laminations for this large wood engraving have mostly failed. The engrain blocks for all but the smallest wood engravings are typically laminated.

AN ASIDE

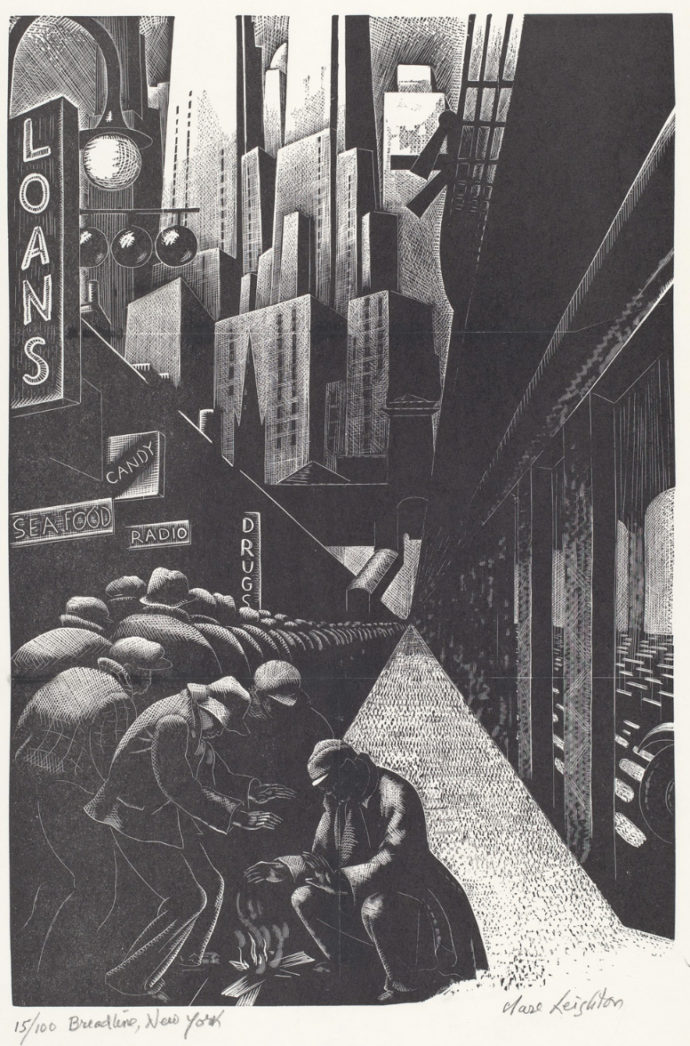

Joint failure is one of the horrors of wood engraving. Here is Breadline, a wood engraving by Clare Leighton (1898-1989). You can plainly see that the joints are failing. Yet she signed and numbered this print. One of the opportunities missed in my early collecting days was not buying a copy of this print from Betty Duffy of the Bethesda Art Gallery in the early 1980s. Her copy–I believed number 5/100–had only the beginning of a split between the N and the S of the LOANS sign. Leighton tried to hide that issue with a few dabs of ink. On two visits to the gallery I refused to pay $250 for it. My loss.

After complimenting Brangwyn on his “nervous stabbing” woodcutting style, Furst wrote: “Unfortunately Brangwyn is far from pedantic in the handling of his own reputation. Cuts associated with his name are not always cut by him, and occasionally he will get an engraver to put a tone on a block that is otherwise of his own cutting…; the illustrations for the book ‘Belgium’ published by Kegan Paul, were cut in wood very ably by H. G. Webb and C. W. Moore.”

Like The Modern Woodcut, I had purchased a copy of Belgium (Frederick A. Stokes Company, New York, 1916) from Kelmscott Books in the early 1980s. Sure enough after the list of the 52 “illustrations” (as they are called in the book), Webb and Moore are credited with engraving about half of the blocks: 15 by Webb, 10 by Moore. So I guess Brangwyn should be credited with cutting the other 27.

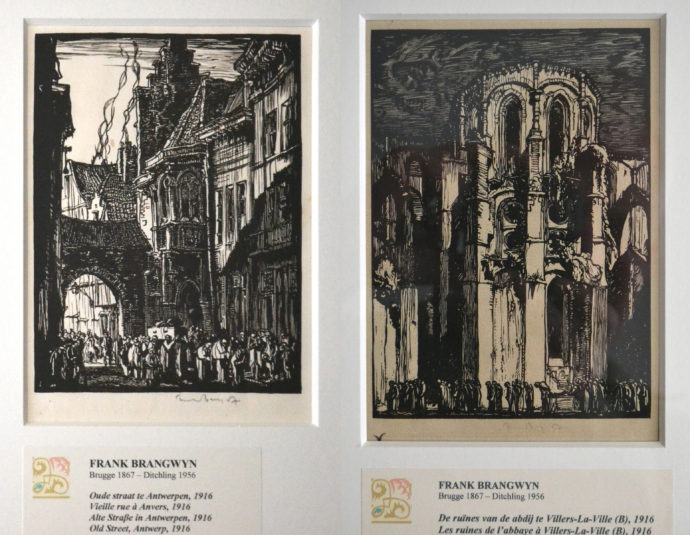

In 2014 I had the pleasure to travel to Bruges. While there I made a point to going to the Arentshuis museum, a former 18th-century mansion that devotes a whole floor to the works of Frank Brangwyn. Bruges might seem odd to be the home to a museum largely devoted to an Englishman. According to Libby Horner in her book Brangwyn at War (Horner and Goldmark, 2014), Brangwyn was born there in 1867 as his English father worked on architectural projects and ran an embroidery atelier. In 1874, the family moved to Great Britain. Horner wrote: “Retaining a deep affection for the city of his birth and the country as a whole which he visited many times during his life, he desired to ‘give to the town of my birth a humble record of one of its sons,’ and through gifts made in 1927, 1936 and 1937 Bruges boasts the largest collection of Brangwyn works in the world, housed in the Arents House.”

The above prints–both signed by Brangwyn–were on display when I visited Arentshuis. The one on the left, Old Street, Antwerp, is #29 on the list of illustrations in Belgium. C. W. More is credited in the book as the engraver. The one on the right is Ruins of the Abbey, Villers. It’s #35 and its engraving is credited to H. G. Webb.

The Arentshuis labeled those prints as woodcuts, not wood engravings. Furst also labeled his Brangwyn illustrations as woodcuts. Maybe he just didn’t make a distinction between the two wood-based, relief-print mediums. Malcolm C. Salaman in his 1927 book The Woodcut of Today: At Home and Abroad (The Studio Ltd, London) didn’t make the distinction either. He clearly illustrated both woodcuts and wood engravings. And he omits Brangwyn prints except for a color woodcut that was cut and printed by Yoshijiro Urushibara.

In an email, Horner commented: “Most people in the UK in the last century referred to wood engravings as woodcuts and many still do, not appreciating the difference. As far as I know FB [Frank Brangwyn] only made wood engravings, and one can see from the size of the blocks that he was using small pieces of boxwood rather than larger blocks of softer woods.”

Back to my chronological progression: When I walked into legendary print dealer Paul McCarron’s shop in New York in 1987, I was quite primed to jump at the opportunity to purchase The Exodus for $85. The price may have reflected a question about whether it was an original print. Clearly Brangwyn signed it. But the printed words must have given McCarron pause. Despite the word “woodcut,” the medium is wood engraving. So had Horner labeled it in her book Brangwyn at War. She wrote: “As with the oil painting of the same name, it is highly likely that this wood engraving was the result of Brangwyn’s anguish at the fate of Belgium during the Great War, although London BM [British Museum] felt that the people were Israelites.” This print is very similar to Via Dolorosa in that the action takes place across the image limited depth of field.

Furst also mentioned The Exodus: “Another good woodcut showing Brangwyn’s glyptic [Furst’s italics] is ‘The Exodus,’ printed in Mr. Shaw Sparrow’s ‘Prints and Drawings by Frank Brangwyn.’ ” Perhaps my copy of The Exodus has something to do with the Shaw Sparrow publication. In the bibliography to Brangwyn at War, the book was listed as: Shaw Sparrow Walter, Prints and Drawings by Frank Brangwyn with some other Phases of his Art, London: John Lane Company, 1919.

A check with AbeBooks.com found listings for the book under Walter Shaw-Sparrow. One listing said the book included “1 double-page woodcut.” I would be surprised if that spread wasn’t of The Exodus. (In fact the image of The Exodus in Brangwyn at War has a fold and, ergo, was photographed from a book.) So I contacted two of the book dealers who had posted the Shaw-Sparrow book. One dealer responded: “This book contains the double page spread of the Woodcut ‘The Exodus.’ ”

Since my copy has no center-page fold, it wasn’t removed from one of the books and its sheet of paper is larger than the book dimensions. So this sleuthing confirms that my print is original and was printed about the time when the book was published. Perhaps it was bonus for a special edition of the book, but none of the listings on AbeBooks.com mentions a separate print or a limited special edition.

Yoshijiro Urushibara

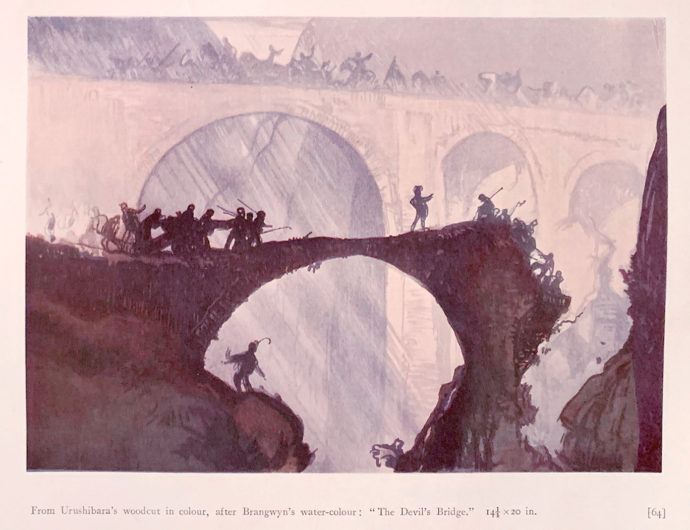

The above image of The Devil’s Bridge appears in Furst’s The Modern Woodcut. About this color woodcut Furst wrote: “Excellent reproductive work on soft wood in the Japanese manner is being done by a native of that country, Urushibara, in London. His reproductions of Brangwyn’s water-colours and of his own designs, necessitating numberless printings, are admirable, but for Europeans constitutionally ‘inimitable’–that is to say: not to be imitated.”

A check in Salaman’s The Woodcut of Today found one black-and-white image of the color woodcut (Walls of Avignon) collaboration between Urushibara and Brangwyn. The image appears amongst Great Britain woodcuts, but Salaman did not mention it until the beginning sentences of the “The Woodcut in Japan” chapter: “We have had so long among us in Mr. Yoshirigi [sic] Urushibara, a Japanese artist, who cuts and prints his own designs, that it would seem to be a natural thing, but as a matter of fact, it was as the faithful interpreter of Mr. Brangwyn that Mr. Urushibara made his first hit. Mr. Urushibara’s own work, Roses, in a vase of many colours, is beautifully set within the plate.”

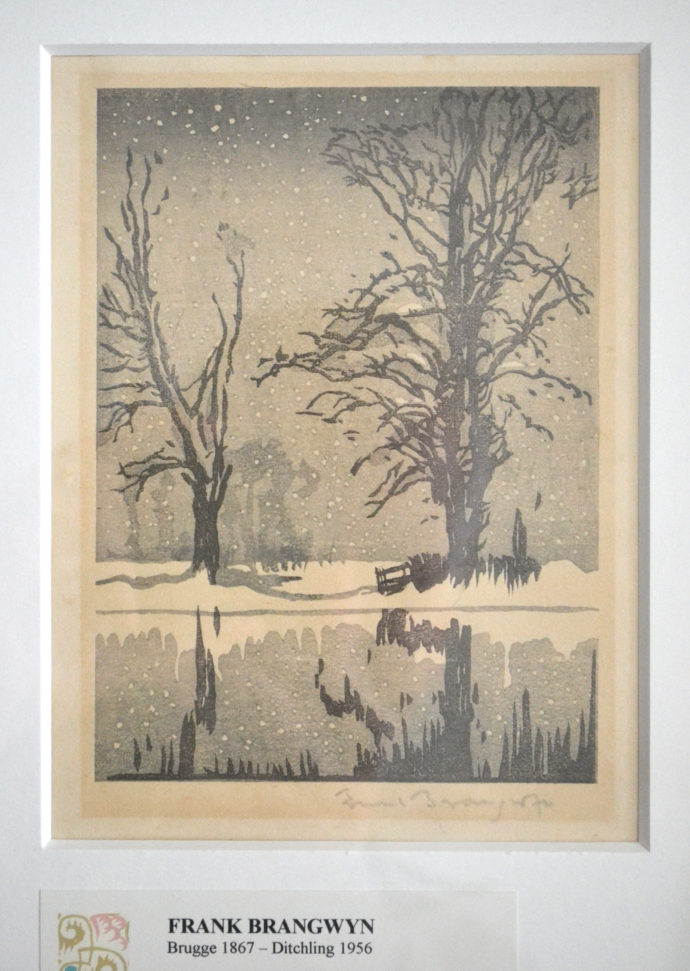

That was my introduction to Yoshijiro Urushibara (1889-1953). My interest was piqued but stayed dormant until my 2014 visit to Arentshuis museum in Bruges, Belgium. For the first time I saw images from his book Ten Woodcuts. I didn’t photograph any of those plates, but I did shoot Trees in a Snowy Landscape, for which Urushibara cut and printed the blocks.

Over the years I did come across plates from the book Ten Woodcuts on various print dealer websites. Dan C. Lienau’s The Annex Galleries currently (March 2019) lists four of the plates. With each listing the Description reads: “This color woodcut was included as plate 6 [for example] in a portfolio titled ‘Ten Woodcuts by Yoshijiro Urushibara’ done in 1924 and published by John Lane in London in 1924. The portfolio included an introduction by Laurence Binyon. The woodcuts were cut and printed by Urushibara after watercolors by his friend and collaborator, British artist Frank Brangwyn.”

Well, for me none of the images–lovely that they are–never exuded the power of Brangwyn’s black-and-white relief prints. But the idea of having a copy of Ten Woodcuts was firmly planted, especially by the Arenthuis visit.

The planets aligned–availability, affordability, condition-wise–finally last fall when I agreed to a counteroffer by Eric van den Ing of the Saru Gallery.

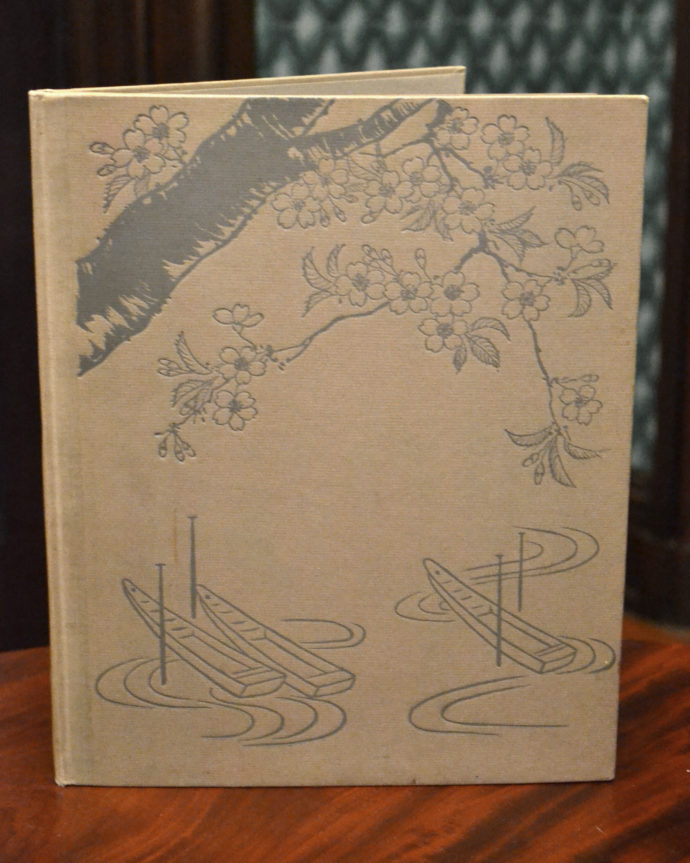

Even before opening I was struck by the sensitive Oriental feel of the cover. While all 10 color woodcuts inside were derived from an Englishman’s designs, there was nothing Occidental about the cover.

After spending some time absorbing the color woodcuts, I realized that there was nothing English about the imagery. Istanbul was the source for three plates, Cairo for one, France for two, Belgium for three, leaving only In the Docks as location uncertain. This port scene could easily have been in England, but Antwerpen in Belgium is a busy port city.

Here’s a sentence from JVJ Publishing’s online page on Brangwyn: (LINK) to help one appreciate the geographic variety of his designs: “In 1888, he worked on a freighter for passage to the Near East of Istanbul and the Black Sea. Orientalism was a major force in European art at the time and Brangwyn was as seduced as many artists were with the colors and light of the Mediterranean and African coasts.”

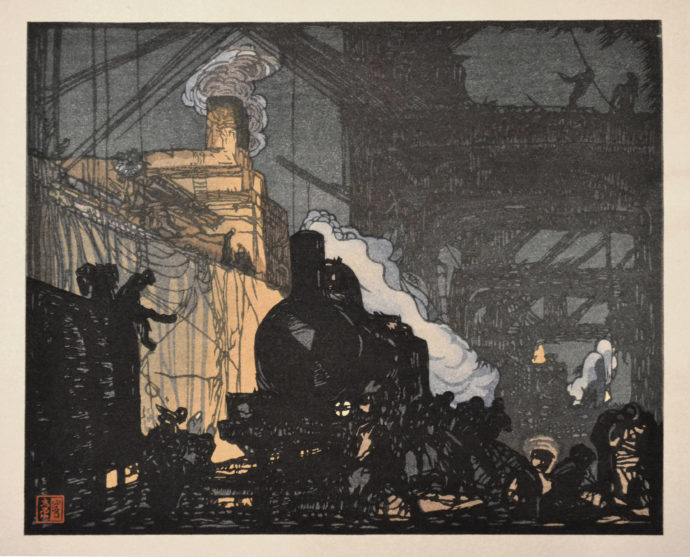

Yoshijiro Urushibara, “In the Docks,” Plate 8 in “Ten Woodcuts,” 6 7/8″ x 8 3/8″ (The book was numbered 162 from an edition of 270, so one could say this print is 162/270. Also note Urushibara’s red seal on the lower left of the image.)

Laurence Binyon, a Deputy Keeper in the British Museum, in his introduction to Ten Woodcuts wrote:

“But Mr. Urushibara has become best known in England through his association with Mr. Brangwyn. He has engraved and printed a number of colour-woodcuts after Mr. Brangwyn’s design. The latest of these are now published in this volume and are among the happiest fruits of this collaboration. Knowing the limitations and the special resources and felicities of the wood-block medium, Mr. Brangwyn provides just the kind of subtly simplified colour-design which best suits Mr. Urushibara’s art. But let no one imagine that the translation is easy and a merely mechanical affair, or that such qualities of tone and atmosphere and luminosity can be gained without long experience and peculiar skill.

“Only those who have seen Mr. Urushibara at work can appreciate what such mastery means. The cutting of several blocks–a block for each colour, besides the key-block–requires both strength and delicacy of hand. But the printing is an even more difficult and delicate art. No press is used; the paper is rubbed at the back for each impression. The simplest of devices secures, in skilled hands, the perfect register which is all-important for successful printing on the same sheet. But the chief difficultly lies in the fact that the paper has to be damped for each impressions, and is therefore always contracting and expanding. The successful printer has then to know to a nicety the exact degree of moisture required, and he has to work at high speed or his registering will be at fault. All this means intense concentration and a good deal of physical power.”

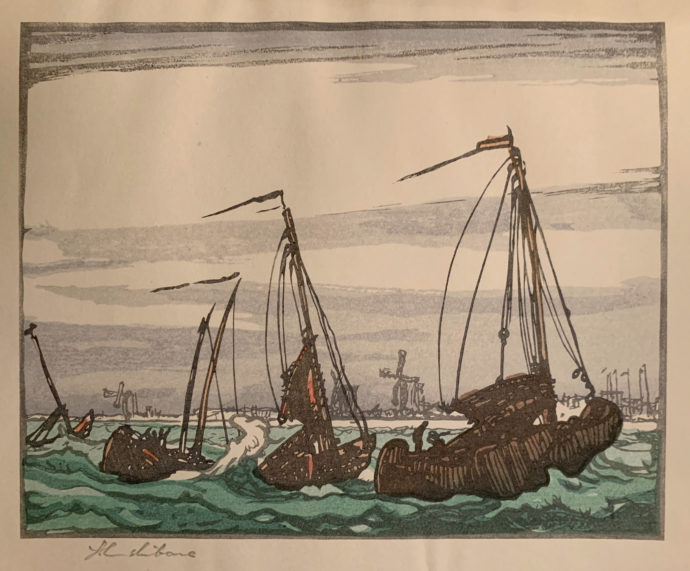

Yoshijiro Urushibara, “Fishing (Entrance to the Scheld),” Plate 1 in “Ten Woodcuts,” 162/270, 6 3/4″ x 8 3/8″ (The Belgium port city of Antwerpen is on the the Sheldt river.)

With the arrival of Ten Woodcuts, I thought it’s time to purchase a copy of Yoshijiro Urushibara: A Japanese Printmaker in London, A Catalogue Raisonné by Hilary Chapman and Libby Horner (Hotei Publishing, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017). Horner wrote the Urushibara biography for the book.

Urushibara was born in Tokyo in 1889 into a family of craftsmen. After his father died when he was quite young, he and a brother were apprenticed to a wood carver. Urushibara’s artistic education largely came from Shimbi Shoin, a firm that “specialized in high-class woodblock reproductions, and for whom Urushibara produced copies of Ogata Korin’s work, printed in vivid colours and with gold leaf…. Shimbi Shoin chose the twenty-one-year-old artist to demonstrate woodblock printing at the very successful Japan-British Exhibition held at White City in Shepherd’s Bush from 14 May to 29 October 1910.”

Subsequently the British Museum contracted with the Shimbi Shoim group to reproduce a famous Chinese hand scroll, a project that Urushibara in part carried out. This led to further jobs for the British Museum throughout the decade. It was through his work for the museum that Laurence Binyon (1869-1943) became enamored with Urushibara’s work and skill.

While Urushibara spent much time in France and worked extensively with artists there, I’m going to highlight his connection to Brangwyn.

Horner wrote: “Urushibara and Laurence Binyon probably met at the British Museum, but no details about the early stages of their friendship are known. Binyon emerges as a pivotal character and stalwart supporter of Urushibara’s. In 1919 he wrote a volume of poems entitled Bruges which was produced in a portfolio, illustrated with woodcut interpretations by Urushibara of Frank Brangwyn’s drawings. This was followed in 1924 by Ten Woodcuts….

“Frank Brangwyn was also an important and influential friend. Quite how the two men met is not known, but they may have encountered each other at the Japan-British Exhibition–the Japan Society played a major role in the organization of the event and Brangwyn was a member of the General Fine Art Committee…. Over the years Urushibara interpreted more than fifty of Brangwyn’s paintings and drawings into woodblock prints, in addition to the portfolios on which they worked together, their relationship being similar between the eshi (painter) and horshi (carver) in ukiyo-e. Luckily some of Brangwyn’s original sketches have survived. These indicate that Urushibara did not merely choose a Brangwyn painting, retire to his studio and produce a woodblock. Brangwyn himself was a good wood engraver and printer and understood the processes, although he probably learnt much from Urushibara.”

Horner in so many words suggested why Ten Woodcuts was presented as a Urushibara project that only he signed either with a penciled signature (five plates) and a red seal stamped within the image (five plates). She wrote: “Brangwyn knew that his friend was experiencing financial problems and that a publication bearing Brangwyn’s name would easily attract sales. He sent a letter to Urushibara enclosing six drawings which he suggested should be scaled to the same dimensions, adding that he would forward ‘that good block of the ship unloading at night’ and that ‘altogether you will make 10, it will be a good book.’ In November 1923, Brangwyn wrote to Mr. Willett of the publishing house The Bodley Head noting that Urushibara was hard up, owing to a costly operation his wife had undergone, and could Willett send him some money. This thoughtful gesture indicated the special bond between the two men.”

Yoshijiro Urushibara, “Black and White Rabbit,” woodcut. (It appears in “Ten Woodcuts” on the page opposite the colophon.)

Addendun

Libby Horner, who in recent years has dedicated herself to everything Brangwyn (FB), reports: “I’ve just published a book about Brangwyn’s “Pots”–flier attached and republished a book on Christ’s Hospital murals for an exhibition the school is running from this April until April 2020. Current project, FB’s prints–etchings, lithos and wood engravings, numbering about 1000 works–hopefully finished in a couple of years!”

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/east-west-woodcuts-urushibara-brangwyn/trackback/