Brangwyn & Eby on WWI

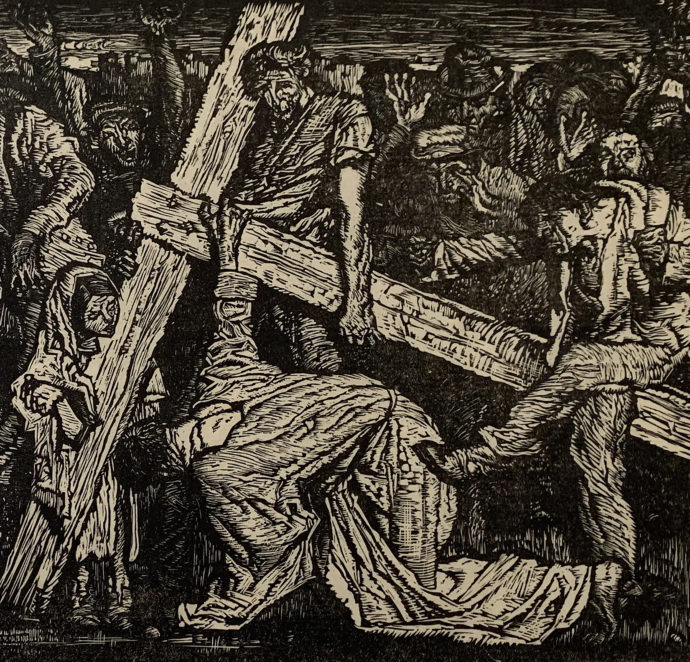

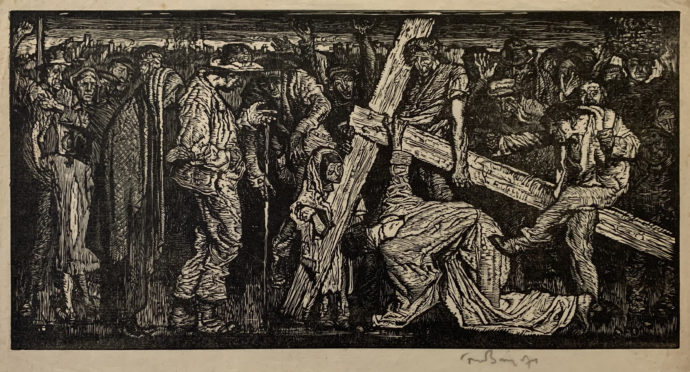

Frank Brangwyn, “Via Dolorosa” also known as “Jesus Falls Below the Cross,” wood engraving, 1916, 19.8 × 38.5 cm (7 7⁄8 × 15 1⁄8 in.)

Introduction

Ever since I acquired a copy of Herbert Furst’s book The Modern Woodcut (John Lane, The Bodley Head Limited, London, 1924) in the early 1980s, I became immensely attracted to a print Furst gave a two-page spread to: Via Dolorosa, woodcut by Frank Brangwyn (British, 1867-1956). Yet it took nearly 50 years before I came across one for sale. And when that happened last November, the sellers on eBay turned out to be longtime collectors of the artist’s work in Wales, UK, who had begun selling off some of their Brangwyns. As John and Anne Morgan emailed me: “We are now in our 70s and with no immediate family are starting the long process of disposal.” Curiously enough, I too am in my 70s and still seem quite mesmerized by the collecting muse. I’m beginning to think that I keep going because of how collecting has brought me so many lovely stories to tell.

This ART I SEE blog post first puts Via Dolorosa into context with both Brangwyn’s World War I era art and another artist intimately connected to the war: Canadian artist Kerr Eby (1889-1946). Last fall was also propitious for acquiring two of his large WWI lithos on eBay. Then the Morgans discuss their fascination with Brangwyn and how they have made their collection available to institutions and art historians.

World War I prints

Frank Brangwyn

For this section I rely on two books: Libby Horner’s Brangwyn at War (Horner and Goldmark, 2014) and Bernadette Passi Giardina’s Kerr Eby: The Complete Prints (M. Hauberg, Bornxville, NY, 1997).

Frank Brangwyn, born in 1867, spent the first seven years of his life living in Bruges, Belgium, where his father made ecclesiastical vestments and vesture. His father moved the family back to England in 1874 and, according to Horner’s book, Brangwyn never took up residency back in Bruges. Yet his childhood years evidently left a lasting impression on him. While he made numerous gifts of his artwork to a number of institutions in England and Austria, Bruges benefited from his largest behests.

In her book, Horner wrote: “Retaining a deep affection for the city of his birth and the country as a whole which he visited many times during his life, he desired to ‘give the town of my birth a humble record of one of its sons,’ and through gifts made in 1927, 1936 and 1937 Bruges boasts the largest collection of Brangwyn works in the world, housed at the Arents House.”

(I had the pleasure to visit Arents House (Arentshuis) museum in 2014. The Brangwyns on display left a lasting impression and are responsible for my pursuit of a copy of the 1924 book Yoshijiro Urushibara’s Ten Woodcuts, comprising ten color woodcuts that Urushibara adapted from sketches that Brangwyn provided him. Upon the book’s purchase, I wrote the 2019 blog post “East-West Woodcuts: Urushibara and Brangwyn.” LINK)

Brangwyn’s best known artistic contributions during World War I were his posters. As Horner wrote; “Despite rumors to the contrary Frank Brangwyn was not an official war artist but he was one of the most outstanding poster artists of the Great War, in terms of quantity, design and technical accomplishment…. It was probably his personal love of Belgium which so enraged and motivated the artist when Germany invaded the country.”

The two Brangwyn war prints presented here are not those posters that were designed to stir patriotic sacrifices in Britain but those that illustrate the effects of war in Belgium.

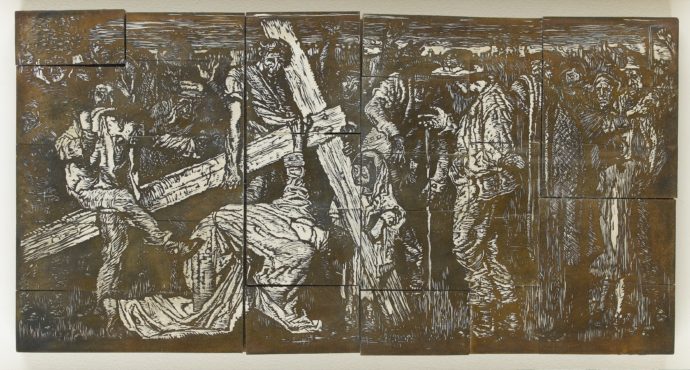

The composite of wood blocks that Brangwyn used to create “Via Dolorosa.” (Courtesy of Liss Llewellyn)

Herbert Furst in his book The Modern Woodcut began his Brangwyn coverage by saying the artist “has taken up the woodcut only since the beginning of the war, when a serious illness kept him from doing the physically strenuous work that has made him famous in both hemispheres.”

Furst continued: “His style in his best and most characteristic cuts is a short nervous stabbing of the wood with the graver, almost analogous to the short stabbing touches of his brush on the huge canvases which carry his mural paintings. It is a style which is entirely his own. The design is in white line, roughly indicated, before the cutting, with chalk, but almost completely drawn in the cutting itself. His finest cut in this style is the “Via Dolorosa….” Furst then called the print J’accuse [I accuse] “inspired by Brangwyn’s general outlook upon life.”

Horner also quoted those Furst lines in her entry on the print, for which she used the title Jesus Falls below the Cross. Then she added: “It may have been provoked by Brangwyn’s sadness at the destruction of Belgium during the Great War, a supposition strengthened by the fact that the onlookers wear contemporary clothes.”

The Goldmark Gallery in England lists a variety of Brangwyn images for sales, including a pair of war posters, a number of war lithographs and the above etching. It’s a zinc etching entitled Via Dolorosa, No. 1, 1918, 30 x 94 cm (11.8 x 37 in.) If the dates in Horner and on the Goldmark website are correct, the etching was completed two years after the wood engraving of Via Dolorosa.

The imagery in above print first appears in Horner as an oil painting Exodus (Outcasting of Belgium) that is no longer extant. About this painting, Libby Horner wrote: “The painting is based on posed photographs which in turn probably relate to Brangwyn’s memories of the aftermath of the Messina earthquake. It shows countless people, all trudging along, obliterating any sky, somehow conveying claustrophobia and the helplessness of these civilians’ lives.” Her entry for the painting included chalk and charcoal sketch and a posed photo, both preliminary works for the oil.

Then in her entry for this print, Horner wrote: “As with the oil painting of the same name, it is highly likely that this wood engraving was the results of Brangwyn’s anguish at the fate of Belgium during the Great War, although the London BM [British Museum] felt that the people were Israelites.”

Referring to “The Graphic Art of Frank Brangwyn,” an article by James Laver in Vol. 51 (1977) of The Penrose Annual, Horner wrote: “Laver considered Brangwyn’s as true woodcuts ‘with none of the finicky work of some wood engravings’ and observed that this work ‘depicted one of the scenes of evacuation which struck the world with horror at that time, but which have since become all too familiar’.”

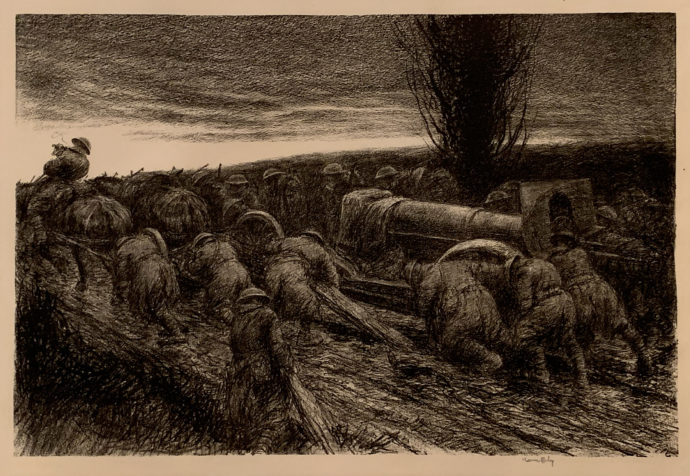

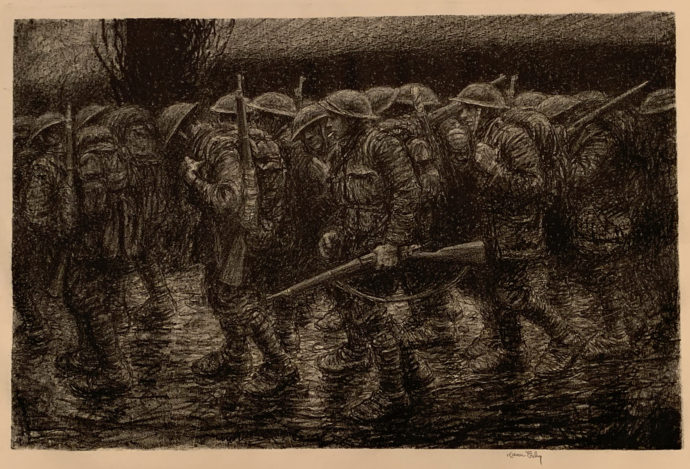

Kerr Eby, “Where Do We Go?,” lithograph, 1919-20, 11 13/16 x 18 3/16 in. (30.1 x 46.2 cm), ed. 75-100

Kerr Eby

Two reasons for pairing the previous two Frank Brangwyn prints with two lithographs by Canadian artist Harold Kerr Eby: Both artists were responding to the Great War, and both artists placed their individuals in a compact space parallel to the picture plane–almost as if the people were part of theater production. (It also happened that the Eby lithos and the Brangwyn Via Dolorosa were acquired within a few weeks last autumn.)

Where Do We Go? was one of four lithos that Eby made based on his experiences in the war. According to Giardina: “He did not print his lithographs, and did not maintain records of either the printers or the numbers printed. The edition size for this print, 75 to 100 impressions, is based on exhibition records.” Like Brangwyn, Eby pencil signed his print but neither dated nor gave any edition information.

(Both Where Do We Go? and Stuck were purchased together on eBay. I didn’t know which I liked better, so I negotiated to buy both.)

The biggest difference between the Brangwyn and Eby prints is that Brangwyn viewed the war from the safety of being in England while Eby experienced the war as a soldier in France.

Eby was born in 1889 in Japan to Canadian parents (his father was a Methodist missionary), who returned to Canada in 1893. Beginning in 1907 at the age of 18, he pursued art studies in New York, first at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn then at the Art Students League, studying under George Bellows and George Bridgman. During the summers of 1913-17 he stayed at an art colony in Cos Cob, CT, founded by John Henry Twachtman. In 1915 at Cos Cob he became friends with Childe Hassan, who received lessons in etching from Eby.

So Americanized had Eby become, that, when the United States entered World War I in 1917, Eby first tried unsuccessfully to get a commission as an artist then enlisted in the U.S. army. According to Giardina: “The war would drastically change Eby’s life.”

During Eby’s service, Girandina wrote, he “first served as a driver in a medical unit of the Ambulance Corps and was later assigned to the 40th Engineers, Artillery Brigade, Camouflage Division, which camouflaged and protected artillery at the front during changeovers from one fighting regiment to the next…. Throughout the war, Eby closely observed the actions of his fellow soldiers, frequently sketching what he saw around him.. [His war prints] attest to the fact that Eby was deeply moved by his experiences on the bloody and deadly war, which left him–and the world–shocked and disillusioned.”

In an appendix to her book, Giardina reprinted an essay by Eby–”War”–that he wrote in 1935 as a second European war was threatening. It was first published by Frederick Keppel & Co. in a catalogue to an exhibition of Eby’s war prints. Then the essay was published in 1936 by Yale University Press.

Eby wrote: “How many divisions had the doubtful blessing of my services I cannot remember nor the names of the places we went–all that is a haze–but what I do remember and brilliantly–is what it looked like and felt like. The men like maggots in a cheese–seemingly moving as aimlessly. The feeling of the night movements. The endless walking in a semi-coma with perhaps your hand on a gun barrel to keep you steady with always the danger of going to sleep on your feet and being crushed by a caisson behind–all these things, the endless piling up of the minutia of the human side of war I remember. And on the advances, the dead. Singly or in windows–always the dead youngsters–the period to what we were doing. It seemed idiotic to me even then, It seems doubly idiotic to me now.”

John and Anne Morgan

Somehow the Morgans and I overcame eBay security about exchanging email addresses soon after they listed a signed copy of Brangwyn’s Via Dolorosa in November, 2020. In their 14 Nov. email, John wrote: “Our collection started over 30 years ago. My wife is a (very) distant relative of Frank Brangwyn being BRANGWYNNE by maiden name.

“Five years ago we handed our collection over to Libby Horner for her research and catalogue. We have many of the large etchings, portfolio and over 200 drawings/sketches and doodles by Brangwyn all of which Libby has seen, and many will appear in her catalogue raisonné. Several are included in her book Brangwyn at War.

“However, we are now in our 70’s and with no immediate family are starting the long process of disposal.”

Excited to contact such Brangwyn enthusiasts, I immediately asked the Morgans to participate in a blog post, which they readily agreed to.

The Morgans’ first Brangwyn purchase was a signed “colotype” of Brangwyn’s watercolor of HMS Implacable. (Courtesy of John and Anne Morgan)

“About 40 years ago,” the Morgans wrote, “we had just about finished renovations on a cottage we had bought and when looking in the local paper in the small ads noticed Brangwyn mentioned. To be quite honest we attended the local auction not really knowing too much about him or the picture. We both liked the picture and to this day it remains in pride of place above our mantelpiece.”

The stern of the Implacable as mounted on the wall of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London. (Photo courtesy of John and Anne Morgan)

“The picture,” they mentioned, is a type of reproduction called a colotype. Libby Horner supplied its details. The image originated as a Brangwyn watercolor in 1915 and was reproduced as a colotype by F. Lewis in 1937, measuring 45 x 60 cm (17.7 x 23.6 in.).

“For some time,” the Morgans wrote, “we could not identify this image but we knew it was neither breaking up of the Duncan nor the Hannibal. Then a friend of Anne’s, over from New Zealand, walked in and said that he had trained on that ship as a young seaman and that it was the Implacable. Amazing!

“On a subsequent visit to the martime museum in Greenwich. London, we were amazed to see the complete stern woodwork hung on a wall with details.

“It seems she was a French warship captured at Trafalgar. In later years it was a training hulk, and after World War II she was offered back to the French for restoration, but with money being tight it was refused. On YouTube there is a very emotional video of the Royal Navy scuttling her off Portsmouth.” (LINK)

So acquiring the Implacable began their Brangwyn foray. They wrote: “Initially we did not intend to collect, but it just happened.”

“Of course when we started there was no internet, and we just saw odd auctions around the country and enquired. Later came “Invaluable,” a monthly subscription service that gave relevant auctions up and down the country, and we bought quite a few items in smaller auctions.

“Later came the internet and more detailed Brangwyn information was readily available. Now eBay makes life a lot easier in many ways, although it came too late for our buying days.”

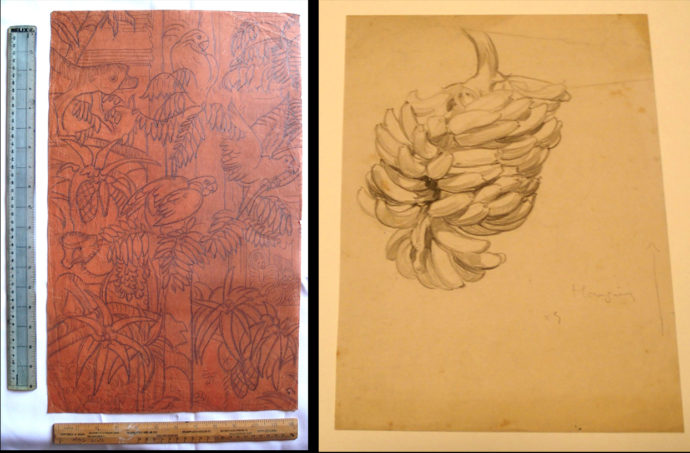

Two of the drawings in the Morgans’ collection that Brangwyn made for his Empire Panels project. (Photos courtesy of John and Anne Morgan)

Most of their additions to their Brangwyn collection, they said, “came bit by bit although there were some group purchases, notably a couple of sketch books and drawings relating to the Empire Panels.” In fact, they have “about 60 drawings directly related to the Empire Panels.” The panels were a huge and ultimately frustrating undertaking by Brangwyn. He began them in 1926 as a commission by the House of Lords to celebrate the British Empire. Faulted as too flamboyant, they were rejected in 1930. In 1934 the panels were installed in the Guildhall in Swansea, Wales. (Here’s a LINK for images.)

The Morgans said they have offered to loan the drawings to the Guildhall “but they have shown no interest.” They added: “Indeed we are at this time negotiating with the House of Lords, Parliament collection for them to go there. They do need to be kept together.”

Quite early on we bought some etchings from L’ombre de la croix. These were very interesting and detailed and led us to buy a beautiful copy leather bound and gilt tooled of the full work. This is now at Campion Hall, Oxford University.“

All told, John Morgan said, “I suppose we have about 30 books, 20 large etchings, one oil, and a couple of hundred drawings and other ephemera.”

The Morgans wrote: “About eight years ago we decided that our drawings and original items need to be viewed by Dr. Libby Horner, and we took them to her. She spent two to three years with them cataloguing them and referencing them for her new catalogue raisonné. Some were used in her recent book Brangwyn at War.

In an email, Brangwyn scholar Libby Horner wrote: “I did catalogue the Morgan’s big collection.” She said she had already published on “FB’s stained glass, war works, ceramics and glassware and am currently finalizing details of his printed work (etchings, lithographs and wood engravings). ”

As mentioned earlier my copy of Via Dolorosa was the result of the Morgans’ decision to deaccession some Brangwyns. John Morgan wrote: “We have recently disposed of a few items as we have no immediate family and the proceeds do supplement our pension!! I wish we could afford to donate, and, if we are ever in that position, I would send to the Brangwyn Museum [Arents House] in Bruges, who are wonderful.”

Addendum

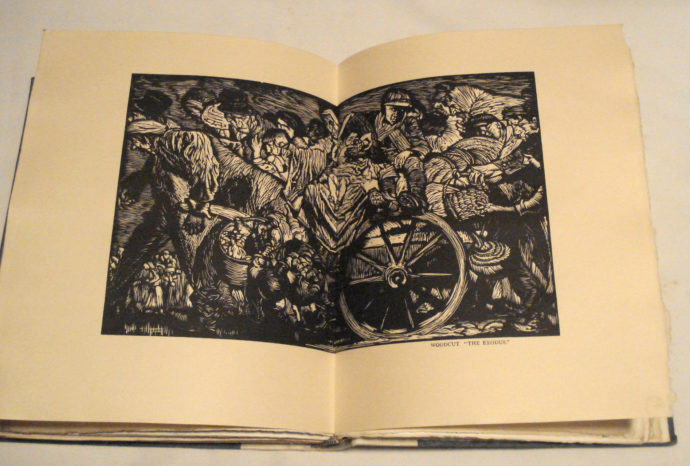

Brangwyn’s “Exodus” woodcut as it appears in Sparrow’s book. (Photo courtesy of John and Anne Morgan)

Communication with the Morgans helped to settle once and for all the origins of my copy of Exodus. They sent me this photo of Walter Shaw Sparrow’s 1919 book Prints and Drawings by Frank Brangwyn (John Lane The Bodley Head, London). Their copy is from the limited edition, numbered 33 of 65. It contains a signed etching and a signed lithograph. My copy of Exodus shared the typography from the book but not the center fold. My guess (and hope) is that my copy was produced at the same time as the book but as an additional bonus.

ONline

- Arents House museum: https://www.museabrugge.be/en/visit-our-museums/our-museums-and-monuments/arentshuis

- Goldmark Gallery: https://www.goldmarkart.com/frank-brangwyn/artist/frank-brangwyn

- Libby Horner’s Brangwyn website: http://www.frankbrangwyn.org/home%202.html

- Liss Lewellyn gallery: https://www.lissllewellyn.com/llfa__w_Artist-Frank-Brangwyn__A_9__r__.htm

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/brangwyn-eby-on-wwi/trackback/