Baltimore Chairs: Plain painted wheelbacks

Introduction

I thought my saga with Baltimore fancy chairs ended in 2021 when I purchased from a Canadian auction house four chairs and subsequently donated six chairs to Riversdale House Museum in Prince Georges County, outside Washington DC. The pair on the left are two of the six chairs I donated. The pair on the right are two of the four chairs bought at auction. The reasoning for the exchange is detailed in my May 2022 ART I SEE post “Finlay Chairs? A Question of Attribution.” (LINK) But the short answer is: “It’s all about the paint,” i.e. the six chairs were mostly repainted, while the four chairs retained most of their original paint. An the quality of the paint on those four chairs opened up questions as to whether they were painted by the artists who worked for the Finlay brothers’ workshop, which produced some of Baltimore’s most celebrated early 19th-century fancy furniture.

Then came a November auction in Petersburg, VA, by Tidewater Galleries, and my Baltimore fancy chair saga resumed. Let me explain why it happened–or should I say, justify why it happened.

Simply painted wheelback pair

My reaction on seeing these on the liveautioneers.com website was that they look simply sporty in their yellow and brown paint. The form exactly matched the six I gave away, and the simplified paint scheme–no stenciling, gilding or classical-inspired designs–actually enhanced the Roman origins of the form.

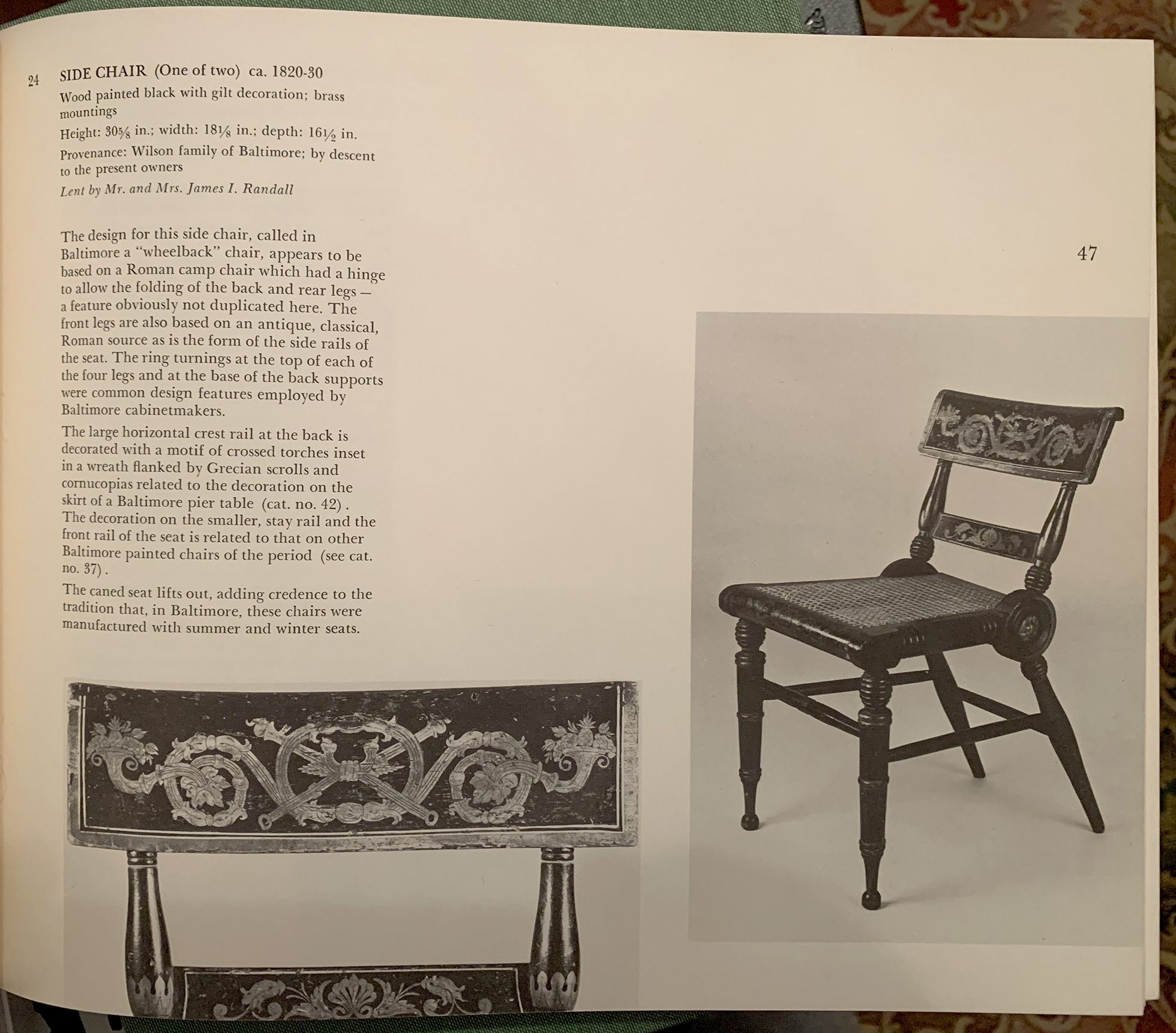

William Voss Elder III’s book “Baltimore Painted Furniture 1800-1840” (Baltimore Museum of Art, 1972) is still the primary source for chairs like these. On pg. 47 he illustrated one of a pair and wrote: “The design for this chair, called in Baltimore a ‘wheelback’ chair, appears to be based on a Roman camp chair which had a hinge to allow the folding of the back and rear legs–a feature obviously not duplicated here. The front legs are also based on an antique, classical, Roman source as is the form of the side rails of the seat.”

He also noted: “The cane seat lifts out, adding credence to the tradition that, in Baltimore, these chairs were manufactured with summer [caned] and winter [upholstered] seats.”

Wanting to assess the originality of the paint scheme, I asked Tidewater Galleries for additional photos.

The photos confirmed (top image) that the chairs have their summer seats attached with screws (the screws sit in later holes), that chairs retain their stamped brass bosses in the center of the “wheel,” and that (lower right photo) the yellow(ed) paint sits directly on the oxidized, unpainted wood of the slip (removable) seat, i.e. that the yellow paint does not cover an earlier paint campaign. These photos also indicate that the photos posted online were too yellow. Perhaps the unweathered paint color was closer to buff (maybe even white) than yellow.

On the online photo of the pair of chairs the paint on the chair on the right appeared cleaner, brighter and less mottled. Was it more recently painted? And the caning differs too. Those questions wouldn’t be answered until I had possession of them.

Other issues for painted furniture

These photos illustrate that simply painted Baltimore chairs like these that Copake Auction offered in May 2011 were not that uncommon. The pair offered by Tidewater, however, are the only ones in the robust wheelback shape with such a simple paint scheme.

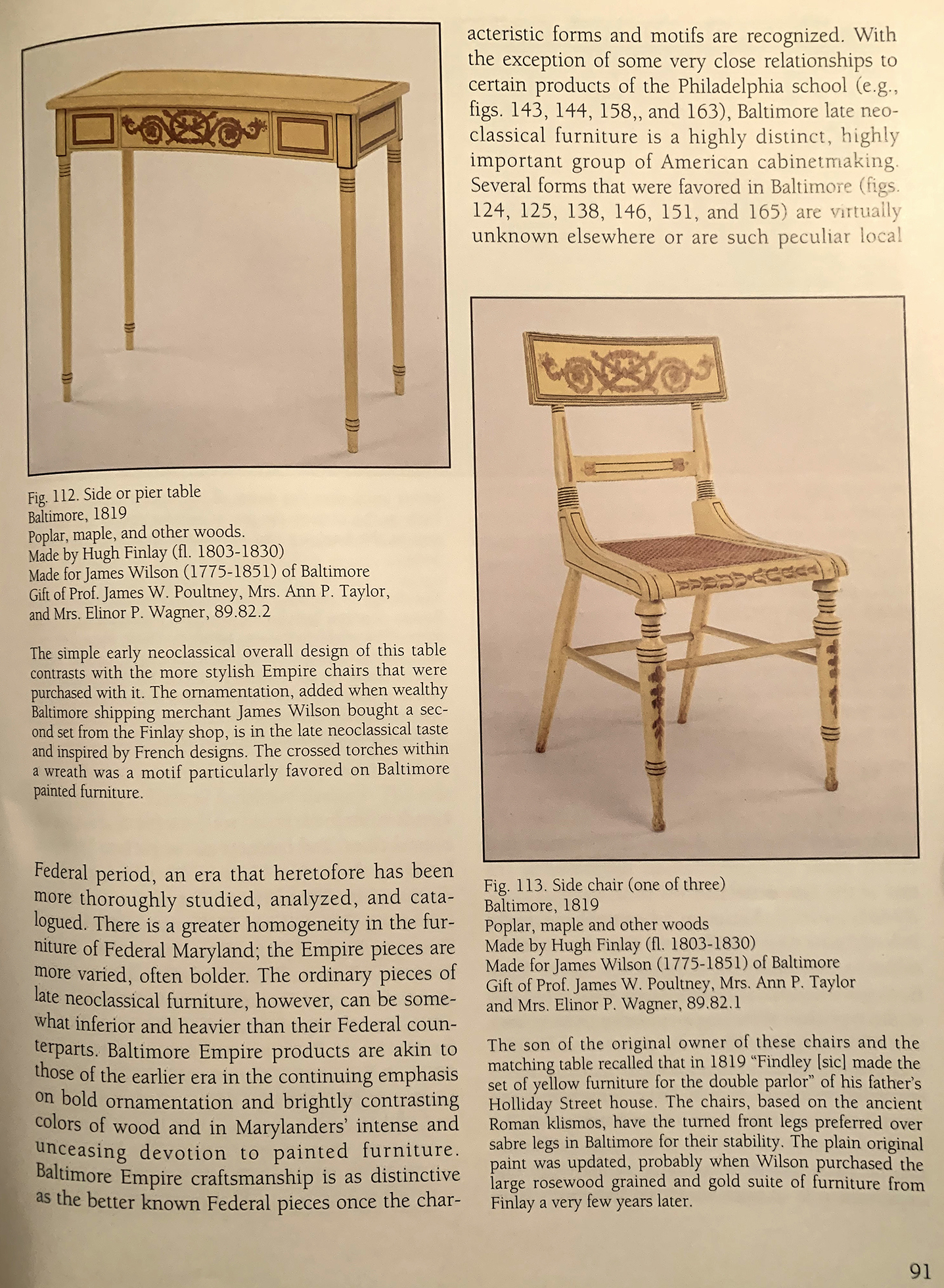

And since the topic of paint and original paint is foremost in this discussion, I want to introduce this page from “Classical Maryland 1815-1845” by Gregory R. Weidman and Jennifer F. Goldsborough (Maryland Historical Society, 1993). Both photos are of furniture made by the Finlay shop in 1819. The captions for both pieces indicate that paint scheme for each became more elaborate after they initially left the Finlay shop.

For the table, the authors wrote: “The ornamentation, added when wealthy Baltimore shipping merchant James Wilson bought a second set from the Finlay shop, is in the late neoclassical taste inspired by French designs.” The “crossed torches within a wreath” were then noted as elements added to the decorative scheme.

For the chair, the caption reads: “The plain original paint was updated when Wilson purchased the large rosewood grained and gold suite of furniture from Finlay a very few years later.” Here the crest rail was also adorned with crossed torches within a wreath. Probably the descending leaves on the front legs and the design on the front chair rail were added at the same time.

So imagine both pieces without those decorative additions. Would their initial paint design be all that different from my newly-added wheelbacks?

This evolution from rather simple to more elaborate paint scheme was also noted in “American Painted Furniture” by Cynthia V.A. Schaffner and Susan Klein (Clarkson Potter, New York, 1997). On pg. 69 in the Baltimore chapter, they wrote: “In the early neoclassical period, furniture was painted a single ground color, but in the new style of the Empire Period, the furniture was painted with a grain to simulate rosewood. Some pieces were embellished with stenciling, freehand brushwork, pigment powdered, and gold leaf.”

In the preceding paragraph Schaffner and Klein attempted to mark when the Empire (also called the late neoclassical) period began. They noted that at the end of the War of 1812 (concluded in Feb. 1815) a design book of the British Regency by George Smith and another by Frenchmen Charles Percier and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine were very influential. But not every fancy furniture patron made that esthetic switch from early to late neoclassical (Empire).

So instead of thinking of these wheelbacks as being a cheaper alternative to rosewood grained chairs with stenciled, gilt and hand-painted cartouches, maybe I should think of these chairs being made for patrons who preferred the more chaste early neoclassical esthetic. In one regard the wheelback form represented the fully developed Empire (late neoclassical style), while the paint scheme harkened back to the earlier esthetic.

And as I fret about originality of paint on early 19th-century furniture, I should keep in mind that changing the paint scheme during the period was not that uncommon. Maybe the better question would be: Was the current color and paint scheme done during the period or added/amended much later. For instance some 18th-century chairs, particularly Windsor chairs, got some painted embellishments in the early-to-mid 19th century when fancy furniture was all the rage.

These photos of James Wilson’s furniture also serve as example of yellow being a base color of choice for many pieces of Baltimore fancy furniture. White paint was not unheard of either (Elder, pg. 48 for example). In fact, Dean A. Fales Jr. in his book “American Painted Furniture 1660-1880” (Bonanza Books, New York, 1972) wrote on pg. 105: “Many of the highest-style examples of American Federal furniture have white as the background color.” So whether my new pair turn out to be yellow or white, they would have been fashionable in early 19th-century Baltimore.

The Cleanup

When we picked up the chairs in Richmond (long story), I immediately assumed the difference in appearance in the chairs was due to one chair being rather clean and one chair needing cleaning. I think in the photo above you can see which is which.

The caning on the chair on the left has a line of breaks near one of the wheels, but I decided to leave as is and place it where it wouldn’t likely be sat on. The other chair’s caning is still able to accommodate a sitter perhaps because heavier gauge cane was used.

It was also immediately apparent that the seat canings were done at different times. The image on the left is of the dirtier chair and has a lighter gauge cane than the one on the right. The caner of the chair on the right also ran cane along the perimeter of the seat, a style not followed by the caner on the left. Because of the fragility of caning, it’s rather safe to assume neither seats have original caning.* Note that the paint is heavier (with craquelure) on the top of the slip seats than the paint on the chair frame itself (to the right on each photo). The cane on both chairs was painted (as was period practice).

*In a 2016 blog post “Marble Pier Table & High-Back Fancy Chair” I noted that the caning on the back of the chair was likely to be original because some red paint used on the wood stiles of the back was brushed onto the caning. (LINK)

I assumed the yellowing of the chairs’ appearance was due principally to aging of a shellac finish. Since shellac is soluble in alcohol, I turned the dirtier chair over and gently stroked an inside surface of a wheel with a cotton swab soaked in denatured alcohol. Expecting only a slow brightening of the paint, I was quite surprised to see the area immediately turn white.

Instead of saying “eureka” white paint, my reaction was a cautious “that’s too white.” I’m not a furniture conservator and I wasn’t willing to take the chairs all the way back to white for fear that doing so would removed part of their history. Cleaning was within my skill set, however. I would proceed with a gel detergent that I could apply to small areas at a time with cotton swabs and then wipe away the released grime.

So I started with the top of a rear leg and the nearby wheel and stamped brass boss, then slowly worked my way around the seat rails and slip seat. I left the caning untouched. Then I turned to the chair back, finally the legs and stretchers.

Two images of one of the wheels on the dirtier chair, before (right) and after (left) cleaning. Even the brass got a little bit brighter. Chipped areas expose a light grey primer coat.

The cleaner chair, which only received only spotty cleaning, stands on the table, while the formerly dirtier chair has undergone cleaning and is on the floor of my studio.

The pair of wheelbacks now grace the front hall. They bracket a Baltimore pedestal cardtable, an 1820s product and a contemporary to the chairs. Above is a Asa Munger 8-day shelf clock, 1828-30, from Auburn, NY. To the left of the clock is Last Trumpet, a 1937 wood engraving by Boris Artzybasheff. To the right is East River Swimmers, a 1937 lithograph by Cecil Bell. I made the floorcloth around 1995.

Some future owner of the chairs may have the surface cleaned so that they appear white. But for now they’ll bask in the glow of a 200-year-old patina.

★★★★★

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/baltimore-chairs-plain-painted-wheelbacks/trackback/