Tetouan: Art I Make

Introduction: Overseas art residencies

Every once in a while I scroll through the listings of artist residencies listed by the Dutch website TransArtists. In August 2017 I came upon Green Olive Arts in the small northern Moroccan city of Tetouan. I read the listing there, then linked to the Green Olive homepage. I liked the studio arrangement and the fact that the program was run by American expats. I also liked that applicants are vetted with a Skype interview soon after they sent in their application. And I was intrigued about Morocco. I wondered: How had it changed since 1986, when I last visited the Kingdom of Morocco?

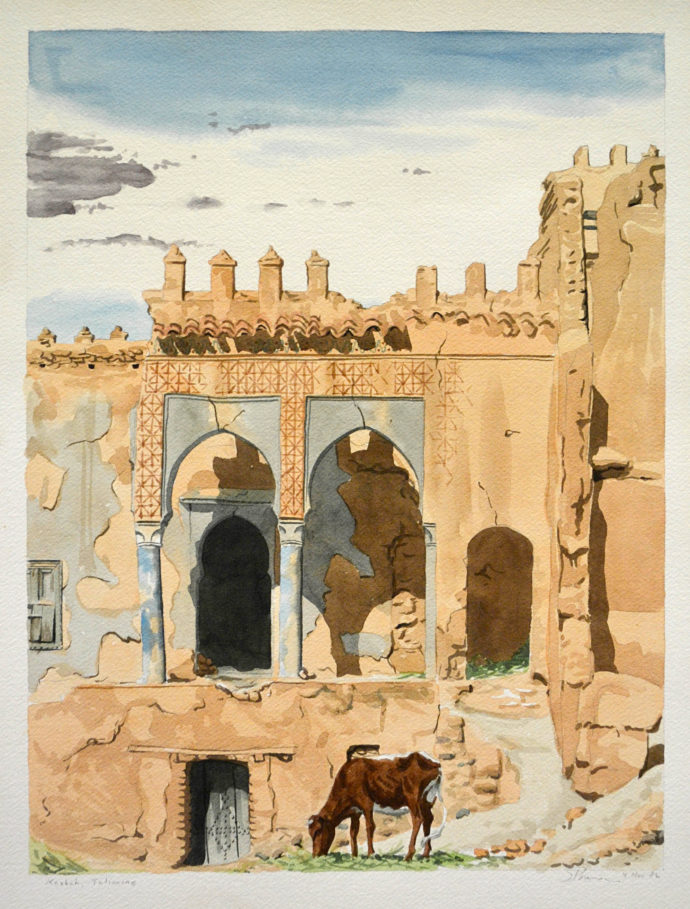

Scott Ponemone, “Kasbah, Taliouine,” watercolor, 16″ x 12″, 4 Nov. 1986.

Naturally I was a very different artist back then. I had the patience and time to do this watercolor on site. I still cherish the memory that, while I was painting inside a crestfallen kasbah in southern Morocco, a gentlemen in a traditional djellaba approach carrying a silver tray with a glass of hot mint tea and a plate of almonds. He placed it beside me and left. Dozens of squatters had made their home there, and I didn’t see where he came from or went. So when I was finished, I just left the tray and kept the memory.

Scott Ponemone, “Csopak IV, Sunflowers,” watercolor, 13 5/8″ x 22″, 18 July 2005.

Before delving into the merits of Green Olive Arts, let me briefly describe my three previous residencies overseas and give a sense of what I accomplished there.

My first overseas artist residency was 2005 in Hungary. Beaty Szechy, a Hungarian artist who taught in a college in Texas, created the Hungarian Multicultural Center artist residency in the early 1990s. I joined 11 other artists-all Americans-for a few days’ orientation in Budapest. Then for the rest of the month of July we stayed at guesthouse in Csopak, close to Lake Balaton. The place had no studio facilities, which peeved many. We cooked our own dinners and rebelled against the lunches provided. In 2005 my paintings involved combining bits and pieces of architecture and decorative arts from the places I visited. In Csopak, the “bits and pieces” including anatomy from fellow artists. I began by asking folks to model their thumbs, then noses, then eyes and, in this painting, their ears.

Scott Ponemone, “Rochefort E, Snails,” watercolor, 18 3/8″ x 12″, 11 May 2007.

Two years later I was still collaging bits and pieces, but when I spent the month of April 2007 at the chateau in Rochefort en Terre, a picturesque village in Brittany, France, I wanted to add a new element: the sky. The Maryland Institute College of Art administered the Alfred and Trafford Klots International Program for Artists, which was founded by Isabel Klots (the daughter-in-law of Alfred and wife of Trafford) in 1989. The wing of the chateau where the visiting artists stayed had no studio facilities and a poor kitchen. The chateau grounds were wonderful and overlooked the village’s slate rooftops. The residency was ideal for plein air painting. For this painting I borrowed snails from the garden. They made wonderful models. If they glided too far away, they were happy to start over again.

There I decided to add skies to my assembled elements. But before I did, I needed to practice painting skies. My first effort while sitting under a magnificent copper beech on the property was a failure. The clouds kept moving. What if I scanned the sky until I spied a particular formation that held my attention and then painted it from memory back in my bedroom? It worked immediately. I’ve been painting skies with and without frames (like in this case) ever since.

(Alas, the chateau suffered severe damage during my stay. Part of the roof collapsed over Isabel’s apartment. MICA moved the program to the medieval riverside village of Léhon, also in Brittany. The residency now lasts eight weeks, which all but ends my ability to return.)

Scott Ponemone, “Sky Aipen II,” watercolor, 12″ across, 6 March 2016.

Himanshu Sharma (Photo by Scott Ponemone)

This painting was done on my next-to-last day in a half-built hotel in Manila, a hill station in the North Indian state of Uttarakhand. I was attending PECAH (Program of Exchange in Culture and Art of Himalayas) run my young men from the town of Ramnagar. The month’s stay was divided in weeklong activities. I did a week of yoga and meditation, a week in the kitchen and lastly a week learning a traditional folk painting called Aipen. The border is in the Aipen style. The footprints represent the those of Lakshmi, Hindu goddess of wealth, fortune and prosperity. (Please turn to a blog post I did on my lessons in Aipen.)

I wish I could have spent more time on Aipen. I also wished the hotel had heat and hot water. I wish I hadn’t needed to wear several layers of clothes to bed each night. But I must admit that the young guys who ran PECAH were more than generous and kind, particularly Himanshu Sharma, who taught clay modeling and made me a pencil holder with a tiger’s head.

GREEN OLIVE ARTS

One of the nicest aspects of the Green Olive Arts (GOA) application process is the use of a Skype interview with two of the directors. It literally puts a face in what normally is a distant bureaucratic procedure. We chatted for a good 20 minutes. They had their checklist of questions, and I got to ask them questions in return. Furthermore the lapse time between when I completed the application (29 August) and when I received an acceptance email (19 September) was unusually short. Since I sought a four-week residency in the fall of 2018 (the actual dates being 15 September 2018 to 17 October 2018), I now had a whole year to plan ahead.

Jeff McRobbie (Photo by David Brown)

Jeff McRobbie and Rachel Pearsey, two of the founders of Green Olive Arts, did my Skype interview. Both are artists themselves. They purposely set aside about a quarter of the year for their own projects. Jeff is GOA’s General Director. He has lived in Morocco since 2007 with his wife Nina, who serves as Director of Logistics and Funding. They have two children. Rachel, GOA’s Director of Studios and Women’s Initiatives, has lived in Morocco for seven years. She is single. Peter Herron serves as Director of Community Relations and Eco-tourism. Also known as Butros (which is Peter in Arabic), he has spent eight years in Morocco. He and his wife are the parents of three young children. All of these American ex-pats are fluent in Arabic.

Green Olive Arts offers two types of residencies: 1) like mine, artists work in the winter, fall or summer on independent projects for from between two to six weeks, arrange for their own housing (with Green Olive help) and most meals, and 2) in the spring the Convergence residency involves a common theme (“Uprooted” is the 2019 theme) for artists, room and board inclusive. For details, please check out the Green Olive Arts website.

Rachel Pearsey took this selfie at the conclusion of a Friday couscous lunch.

The facilities at GOA are pretty nice. It’s located on the second floor of a building in the heart of the Spanish new town. (Tetouan was part of the Spanish protectorate that stretched across northern Morocco–except Tangier– from 1912 to 1956. Spanish is Tetouan’s second language.) It’s just a few blocks from the medina. There are three well-lit studios, often shared. A gallery, a supplies/wood shop, kitchen/dining room, a quiet salon, an office and bathroom complete the layout.

Every Wednesday GOA hosts a lunch for visiting artists and a few artists from the community. Each artist is asked to talk about themselves and their art–an ideal way to get acquainted.

For small additional fees, GOA also connects visiting artists with local crafts people. One morning Rachel walked the artists through of the medina to reach Dar Sanaa, the School of Arts and Crafts, where students learn traditional crafts like Islamic geometric painting, wood carving, metal work, wood inlay, weaving and embroidery. Then she introduced us to the Ensemble Artisanal, where skilled crafts people open their studios to visitors. Several artists during my stay connected with members of the Artisanal to create collaborative artworks.

In addition, GOA arranges for lessons in Arabic and Islamic geometry. GOA also offers midnight tours of the Medina with a Tetouan photographer. (More on these activities in the second installment of my Tetuoan blog.)

And on some Fridays artists and staff enjoy couscous together–Friday being the traditional couscous day. Each person gets to consume the wedge of couscous directly in front of him/her. As a left-hander I had to be conscious to place my spoon in my right hand. (Traditionally, left-hand use is reserved for the toilet.) On this day, hidden underneath the caramelized topping of onions and chickpeas were pieces of roast chicken.

GOA is located in the small, vibrant northern Moroccan city of Tetouan, which is a few kilometers from the Mediterranean and about an hour’s drive from Tangier. Here’s a panorama from inside the walled medina. The jagged peaks in view toward the end of the video are the Rif Mountains. The tall cedars trees are within the king’s palace. There are no outstanding architectural monuments there. The few tall structures visible in the sweep of the old city are minarets for the mosques. Non-Muslims are forbidden to enter.

The one aspect of Tetouan that I have no adequate photos for is the liveliness of the streets. People are everywhere–walking, greeting each other, shopping, lounging (mostly men) on chairs outside cafe houses, children running about the expansive Feddan Park. Especially in the medina, shops (mostly tiny “hanoots”) spill out into the alleys. Shopping is a very public activity. (Baltimore streets and sidewalks resemble a ghost town in comparison.)

My Tetouan paintings

My intention in making art in Tetouan was to continue the series of large watercolors that I call “Couples.” Starting in October 2017, the process begins with me walking up to strangers on the street and asking them to pose for me. (I detailed this process in an earlier blog post and provide a complete portfolio of Couples paintings from the series online.)

Roqaya el Guiri (Photo by David Brown)

The problem is that figurative art is not part of the Islamic tradition. In fact the wonderful world of Islamic geometric and arabesque art flowed out of the interdiction against representational art. Or as Jeff McRobbie informed me, I might find a great deal of resistance when I ask Moroccans to model. But to buffer any resistance, he offered the assistance of Roqaya el Guiri, a young woman who regularly helps out at GOA. She would be my “fixer,” to use a journalistic term for a native to work as an introducer and translator for a reporter. Fortunately she was game.

Before hitting the streets, I showed Roqaya images on my phone of previous Couples paintings and explained to her what I would say upon walking up to potential models. Not only did she catch on, but after we stopped a few pedestrians of my choosing, she started to make suggestions on likely models. Best of all, we had a lot of success.

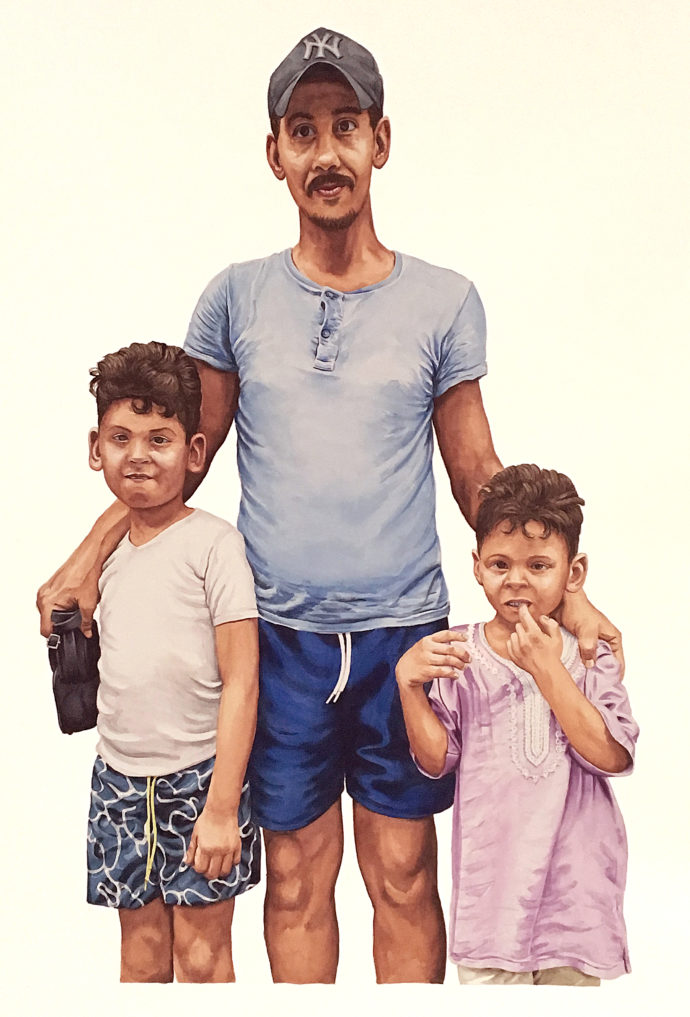

Our first models were a father and his two young sons. Initially I just want the father and one son–to keep my Couples theme rolling–but both sons made for a better image. Then we entered a fabric store. There two sisters modeled for me. I like them because one was more traditionally dressed than the other. Surprisingly the mother and her son also modeled. Then back on the street I photographed three pairs of students. We really didn’t get many “No” responses. Two paintings resulted from my first Tetouan shoot.

Scott Ponemone. “Tetouan: Father & Sons,” watercolor, image 31″ x 19 3/4″, 24 Sept. 2018.

Rachel took this short video of me starting work on Tetouan: Father & Sons.

Scott Ponemone, “Tetouan: Sisters,” watercolor, image 30 1/4″ x 20 1/4″, 1 Oct. 2018

In an attempt to up the ante on my next shoot, I wanted to photograph the gentlemen who with their glass of coffee or tea (and often a cigarette) seem to lounge forever outside cafes. Would guys who partake of this mostly-male tradition be willing to model? For this I needed a make fixer. Rachel Pearsey worked the phones, juggling replies from three male college students. Finally an arrangement was made for Naoufal al Faik, the son of the woman who makes the couscous lunches, to arrive at GOA after class. It was nearly dusk when we set out. Our first attempts were met with “No.” Eventually two middle-aged guys–one in a blue shirt, one in a black shirt–agreed to model. But a third gentlemen in a white shirt wanted to be included. So I shot the initial pair; then I photographed all three; and finally the blue shirt with the white shirt. This was the photo I used.

Scot Ponemone, “Tetouan: Cafe Gents,” watercolor, image 31″ x 22 1/4″, 7 Oct. 2018.

Again I upped the ante for my fourth and last Tetouan Couples painting. What about older women? Could I find older women in traditional dress who would model? Rachel suggested the Jballa market, an enclosed market where women from Jballa villages in the Rif Mountains come to sell their produce. The day after arriving in Tetouan I had accompanied Rachel to the Jballa market so she could hand out certificates to those who couldn’t attend GOA’s 5th anniversary celebrations. Each women greeted her very warmly. And when she sought to buy vegetables, her purchases became gifts. In fact, I couldn’t spend my dirhams either.

Once again Roqaya became my fixer. There was hesitation at first from the Jballa ladies. But Roqaya persisted, and two agreed to model. Each choose to hold up some of their wares. One held up bottles of unfiltered olive oil. (Later in my stay I bought a bottle–quite wonderful. Too bad I didn’t do so when I accompanied Rachel.) The other held two potted plants. The next day I returned and handed each a printout of their photo.

Scott Ponemone, “Tetouan: Jballa Market Women,” watercolor, image 30″ x 21 3/8″, 13 Oct. 2018

While painting those four Couples paintings were my primary goal for my GOA residency, I also did four small circular sky paintings with a repetitive border, much like the Aipen paintings I did in India. They joined the ongoing series of paintings that I call “Planets.” (A portfolio of Planets can be found on my website.)

I did a Tetouan sky painting before each of the figurative ones. Each of these skies were inspired by the view of the Rif Mountains from the balcony off my apartment bedroom. On any given day clouds rolling off the nearby Mediterranean hid the mountain peaks or showed the peaks but not the valley below. But my first Tetouan sky was mostly blue with a few thin cumulus hovering over the peaks.

For the borders I sought out either Tetouan architectural elements, Islamic geometry or a Roman motif since northern Morocco was a Roman colony for many years. With each image of these paintings, I post the source that inspired the border.

Scott Ponemone, “Tetouan A,” watercolor, 16″ across, 19 Sept. 2018.

The source was an arch at the end of a colonnade in the Spanish new city, not far from the parade ground in front of the king’s palace.

Scott Ponemone, “Tetouan B,” watercolor, 16″ across, 28 Sept. 2018

These critters chased each other round the base of a Roman bronze touchier. It was on display in Tetouan’s small archeology museum.

Scott Ponemone, “Tetouan C,” watercolor, 16″ across, 3 Oct. 2018

The border here is my play on Islamic geometry, where hexagons are a basic way of turning a circle into a straight-edged shape. My goal was first to figure out how to draw adjacent circles to fit perfectly around a center circle. Then I toyed with drawing lines to connect points of the hexagons and soon realized this playful up-and-down rotation of yellow triangles.

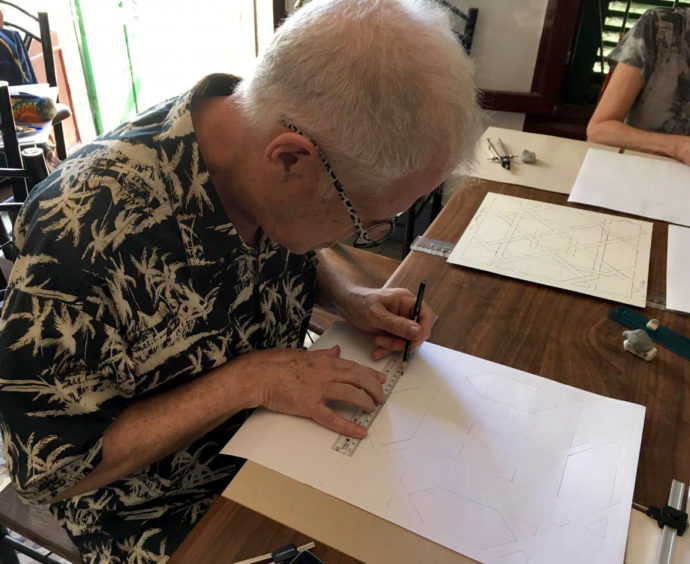

Photo by Rachel Pearsey

This border occurred to me after Ahmed, who graduated from Dar Sanaa, taught several visiting artists the basics of Islamic geometry. It’s all rather magical how use of just a compass and a straight edge can yield–when properly instructed–such intricate work, or in my case an introductory design.

Scott Ponemone, “Tetouan D,” watercolor, 16″ across, 8 Oct. 2018.

Deep in the medina was this intricately patterned entryway to a mosque. The teardrop pattern (near the top) that I selected is but a small part of the carved relief.

One-Day Exhibition

About 10 days before the end of my GOA residency, Jeff McRobbie came into my studio to offer a one-day, one-person exhibition with a poster. I certainly wasn’t expecting the offer. “I’d be honored,” I told him. In turn I proposed to do a Keynote slide presentation about my work at the opening. My offer added to my workload since I hadn’t yet taken the photo of the Jballa women or started the fourth Tetouan sky painting. In fact I wouldn’t complete the Jballa women painting until the afternoon of the opening. And I couldn’t complete the slide show until I could photograph the Jballa painting.

Poster by Rachel Pearsey

Initially I chose the Tetouan: Sisters painting for the poster, but at the last minute Jeff thought better of it. Morocco may be a rather progressive Moslem country in many ways, but modesty of its women is still the social norm. So Jeff thought having the sisters’ image on the poster might bring ridicule upon them and their family.

Photo by Scott Ponemone

Jeff and I went over the exhibition hanging a few days before the opening. We agreed that the skies would be on one wall and the Couples painting on two other walls. The Keynote presentation was projected on a short chamfered wall in between the Couples paintings.

Photo by David Brown

Photo by David Brown

Photo by David Brown

Fortunately a young man, whom I had met during an open-studio tour, became my translator during my slide show.

Photo by David Brown

About 60 people, including many young folks from Tetouan’s art school, came that night. I’m sure there were many budding talents in the room. I certainly enjoyed the one-night’s attention.

I want to thank the Green Olive Arts staff for making this residency so memorable and productive. I applaud the kindness they showed me, the help they provided in arranging fixers, and the friendships the GOA staff has cultivated within the Tetouan community.

Tetouan Part II

In the second Tetouan post I’ll present the other American artists in residence at GOA during my tenure. I’ll also introduce you to Freaky, a painter with a studio in the medina, and Karim, who photographs the medina at 3 in the morning. I’ll also take you to Dar Sanaa, the arts and crafts school, and journey to the blue-walled town of Chefchaouen. Here’s the link.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/art-making-in-tetouan/trackback/

Thank you, Scott, for this lovely presentation. It feels like I have been there. I love your sweet, gentle tone and your attention to the people and details of Morocco. Your paintings of the skies somehow look more mysterious to me when I saw them from afar, as in the picture of the exhibit. The intricate and bold framing of the architectural renderings makes them look like peering through a keyhole into a distant land. Beautiful. Thank you for taking the time to share your experience with us. Your new friend, Noelle