Irwin Hoffman: Etcher of Workers

Introduction

When I first bought prints by Irwin Hoffman, he was still alive. And chances are Betty Duffy, who sold me those prints at her Bethesda Art Gallery, knew Hoffman, as she seemed to be in direct contact with a number of the artists she represented. I first bought prints at the Bethesda Art Gallery around 1980. Duffy opened her gallery in 1975. Hoffman (born in 1901) lived until 1989. Thanks to her, by the time Duffy shuttered her Bethesda storefront, also in 1989, I was a confirmed collector of American prints from about 1920 to the early 1950s–the era her gallery featured. (She continued to sell from her home for a few years more.)

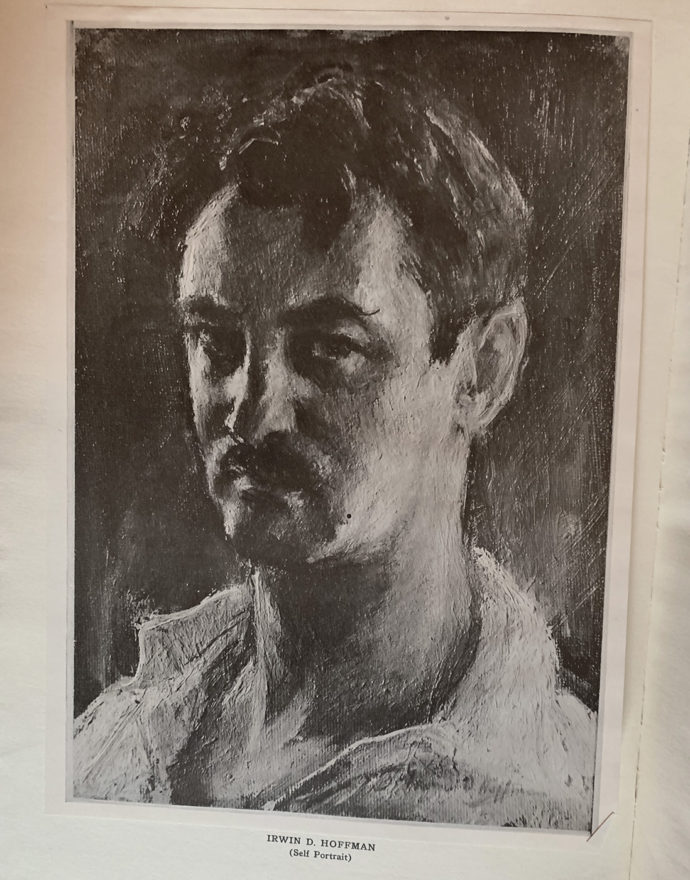

If I only was curious enough in the 1980s to ask Duffy about which artists she dealt with directly, chances are I might have contacted Hoffman and this post would include conversations I had had with Irwin Hoffman. Fortunately I do have two books on Hoffman (Irwin D. Hoffman, Associated American Artists, New York 1936 and Irwin D. Hoffman: An Artist’s Life, Boston Public Library, Boston, 1982) and one book that includes Hoffman (Louis Lozowick, One Hundred American Jewish Artists, Art Section of YKUF, New York, 1947).

The impetus for this post was the recent acquisition via eBay of Hoffman’s The Stoker, 1935, and Rocks & Men, 1937-8. Both are strong images of hard working white men. But let me start with the two Hoffmans I bought from Duffy. Both are of women of color.

South of the Border

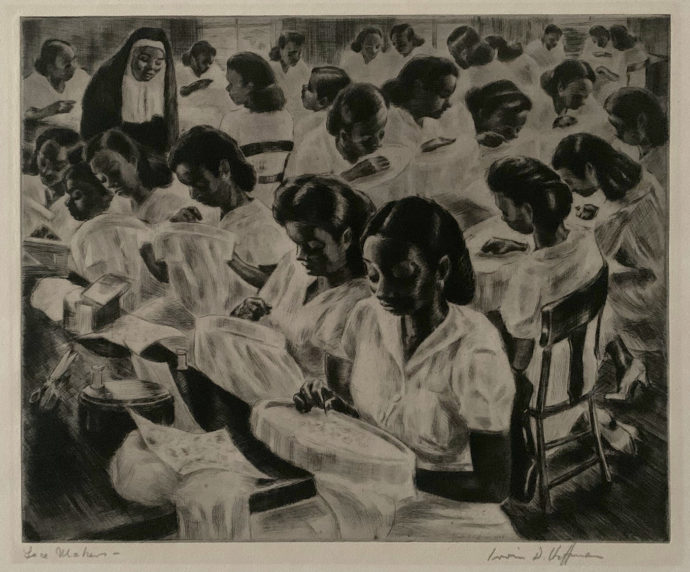

Lace Makers was my first Hoffman purchase. I was attracted to the repetition of the women’s heads and their concentration making lace. At the time of the this writing, Annex Galleries run by Daniel C. Lienau has a copy of Lace Makers for sale. His description for the print reads:

“Lace Makers,” a drypoint, was done in 1944 and published by Associated American Artists (AAA) in an edition of 250. His subjects for this composition is a group of 23 young workers, lace makers, in Puerto Rico, crowded together in a room with a nun as an overseer. The clergy could afford the costs and they commissioned lace works for their vestments and for the outfits worn by the figures of saints. It was also used to adorn clothing for infants and wedding dresses, among other uses.

Puerto Rico and Panama are both known for their fine handcraft lace (sometimes called ‘pillow lace’) which is lace made by braiding and twisting thread on bobbins in order to control it. It was originated in Genoa, Italy, in the 16th century. In Puerto Rico the towns of Moca, Isabela and Aguadilla are most famous for their Mundillo lace.

Hoffman had this comment in the book Irwin D. Hoffman: An Artist’s Life:

This was done in a convent where girls from the outside were taught lace making by nuns. Every one is a portrait. The contrast between the types, black and white, was quite engaging. They were all very expert.

(The book Irwin D. Hoffman: An Artist’s Life was published to accompany an exhibition–”Irwin D. Hoffman: A Retrospective”–that opened in the fall of 1981 at the Boston Public Library. It included commentary by Hoffman on items in the exhibition.)

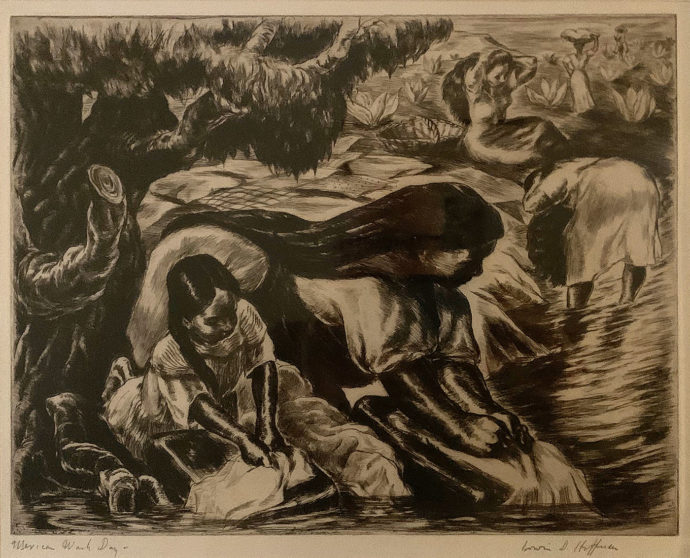

Irwin Hoffman, “Mexican Wash Day,” etching, 1936, 10 7/8″ x 13 7/8″, ed. 191 published by AAA in 1937

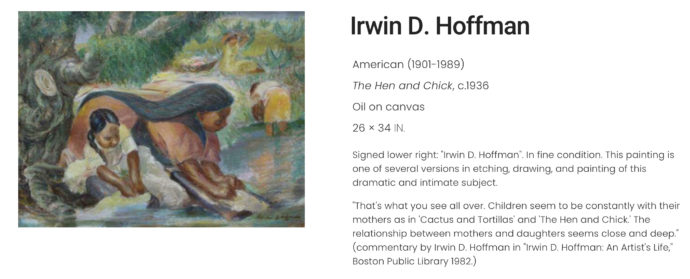

The Boston Public Library books creates some confusion about this print. It illustrates this print but gives it the title: The Hen and Chick–Mexico. Hoffman doesn’t comment on this print, which given the date 1933-35 and dimensions at 10 3/4″ x 13 3/4″. But he did comment on a watercolor called Women Washing: “This is down in Parral in Chihuahua…. They have these terribly dry periods, and the only source of water are these streams that are polluted and fetid. Yet they wash their clothes and everything there…”

The AAA book on Hoffman lists but doesn’t illustrate a print called The Hen and The Chick, soft ground etching, 8 1/4″ x 4 3/4″, 1933. I once did find a small version of this print only showing the mother and child in the foreground. The print illustrated above was not listed in the AAA book because it was printed a year (1937) after the book was published.

Hoffman used the name The Hen and Chick for this c. 1936 oil painting that was sold by Childs Gallery in Boston. The Childs Gallery listing reads: “This painting is one of several versions in etching, drawing and painting of this dramatic and intimate subject.” It appears that when Hoffman could name his wash-day image–as in this painting–he chose The Hen and Chick. But, when the Associated American Artists published his etching, the name became Mexican Wash Day. Prints from this edition have come up for auction frequently. Liveauctioneers.com shows that name Mexican Wash Day was used for this edition 15 times since 2003. The name Hen and Check–Mexico is on only one copy sold at a 2005 auction. Yet the title on that copy appears to be printed, while Hoffman wrote out the titles on the ones named Mexican Wash Day. And one copy at a 2006 auction was untitled.

Margaret Sullivan in her essay in the AAA book wrote: “His Mexican work is an excellent example of this individual approach. Here Hoffman has seized upon the relationship between the peasants and the vast country in which they live as the theme of his portrayal…. Hoffman… was wise enough to take as his province the homely tasks of daily peasant life and throw them vividly against the background of the luxuriant, brooding country.”

The Boston Public Library book includes text from a slide lecture by Theresa D. Cederholm, given during a symposium for Hoffman’s 1981 library exhibition. She remarked: “Hoffman became captivated by the spirit, smells, and sounds of the Mexican land and its people. He returned time and again to indulge his senses and to fill sketchbooks. It is clear that he won their love and respect as much as they had won his.”

North of the Border

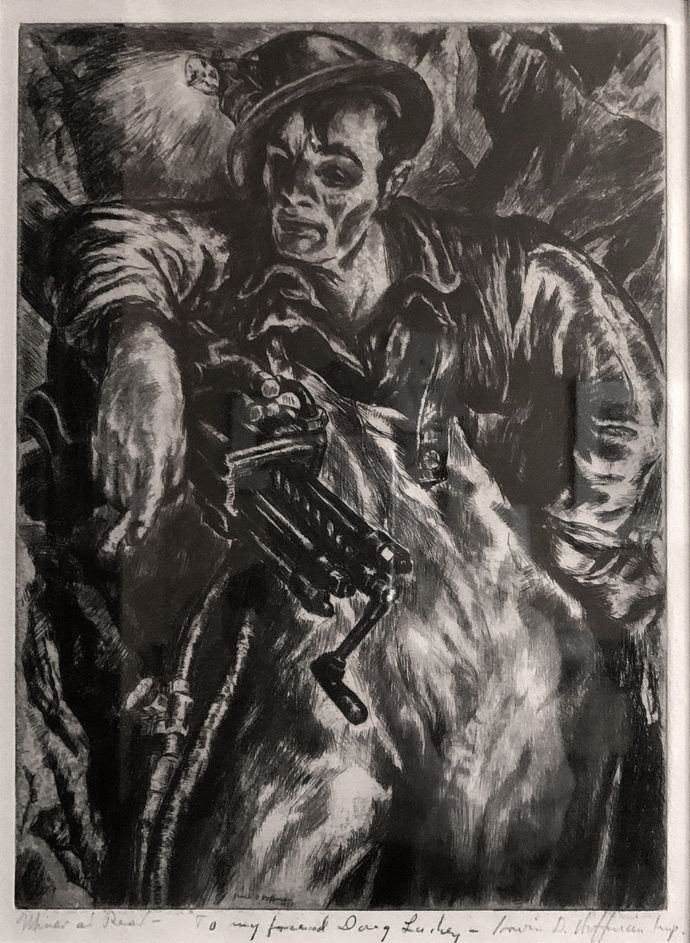

Irwin Hoffman, “Miner at Rest,” etching, 1937, 10 3/4″ x 8″, ed. 50. This print won first prize, the Mary F. Noyes Prize, by the Society of American Etchers, 1937

Wanting to represent Hoffman in my collection with at least one print of a North of the Border industrial scene, I acquired Miner at Rest from Steven Thomas at a large antique show in Baltimore in 2012.

I don’t recollect what Duffy was charging for a similar Hoffman image during the 1980s. But what I paid was less than half what other dealers were charging for the image in 2012, and I see one being offered now at 2.5 times what I paid.

There are definite prejudices involved in evaluating and pricing Hoffman’s prints. One factor could be edition size. Between 1934 and 1945 AAA published 15 Hoffman prints, with editions as large was 250. Lace Makers was in an edition of 250; while Miner at Rest was only 40.

But a better determinate would be subject matter. If one were to separate Hoffman prints by subject alone, images of his Mexican and Puerto Rican subjects would be priced no greater than half the price of images of white working men.

(Hoffman happened not to have done prints celebrating or even denigrating life in New York City. But had he done so, those prints would have been priced above anything else in his oeuvre. Big Apple money has a lot of umph.)

What enabled Hoffman’s Miner at Rest to be affecting is that he went underground to do his sketching. Hoffman was one of four brothers born to Russian Jewish immigrants in Boston. The eldest–David–died when the U.S.S. Tampa was sunk during World War I. The other two brothers–Arnold and Robert–became successful mining engineers, and it was through them that Irwin had access to mines.

In her Boston Public Library essay, Cederholm wrote that Irwin accompanied his brothers “on numerous claim-making expeditions into all regions of the United States, Canada and Mexico…. [He] soon gained the total respect of the men of the mines, as well as that of the inhabitants of the communities in the mining region. When not below ground in miner’s gear, Hoffman roamed the countryside widely, sketching, and talking with the people…. Hoffman’s determination to bring this kind of intimacy to the labors taking place below ground led him down mine shafts throughout North America. The hundreds of sketches, oils, and prints resulting reflect a startling technological accuracy (for the sake of his brothers) as well as the artist’s eye on the very personalized aspects of this subterranean culture.”

A similar Hoffman etching–Taking a Fiver–showing two miners taking a five-minute smoking break is reproduced in Albert Reese’s American Prize Prints of the 20th Century (American artists Group, New York, 1949) because it won the 1940 John Taylor Arms Prize, Society of American Etchers. Reese commented: “Few Artists probed as deeply into the miners’ lives as has Irwin Hoffman, or have treated them with as much sympathy and understanding. Fewer still who have his incomparable flair for putting his knowledge in dramatic form.”

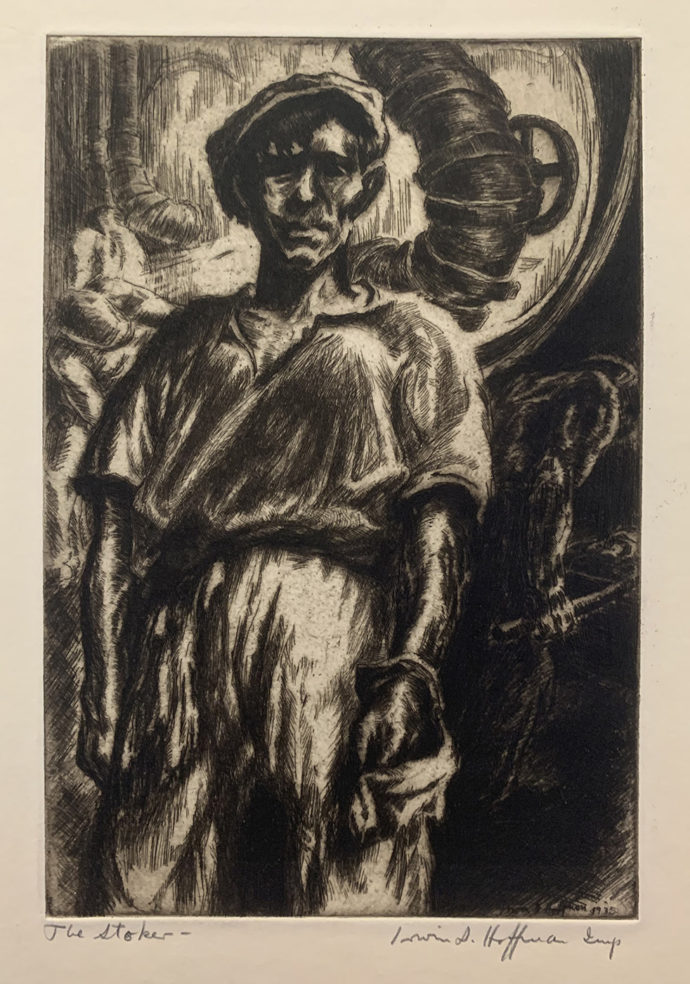

My next Hoffman acquisition came via eBay this winter and resulted in a significant gift–sort of. An eBay seller who said he had bought the contents of a Vermont print shop placed over a dozen Hoffman prints for sale. The Hoffman signatures all seemed correct. The seller photographed each at an oblique angle, often with a tape measure running across them. It was difficult to access the quality of the impressions. I shared this information with a friend and fellow print collector. I said I was interested in The Stoker since it was another strong portrait like Miner at Rest.

In an essay by Sinclair Hitchings in the Boston Public Library book, he wrote: “One of my personal favorites among Hoffman’s prints is The Stoker, etched in 1936. Several of his prints have as their subject single standing figures. The starkness of this hollow-eyed man conveys well as any work of art I know the dignity and the impact of work.”

In the same book, Hoffman noted that the stoker of his print “was on a cruise ship, The Rotterdam. I took a cruise during the Thirties. The ship was torpedoed by the Germans later, of course.” About his The Stokers etching (a horizontal scene with several stokers) Hoffman said, “This was the boiler room of the S.S. Rotterdam that used coal to fire the boilers.”

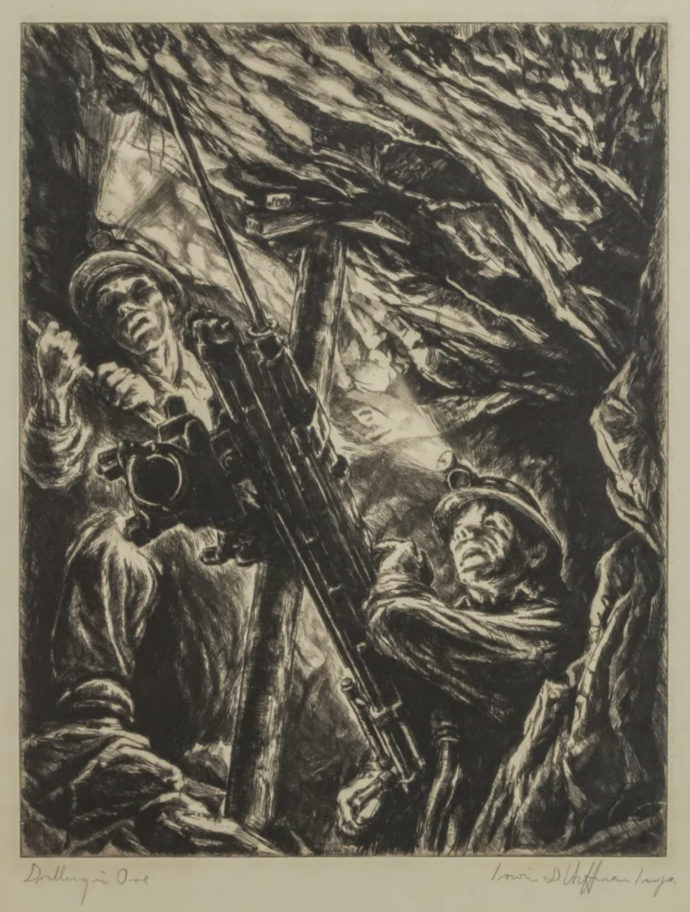

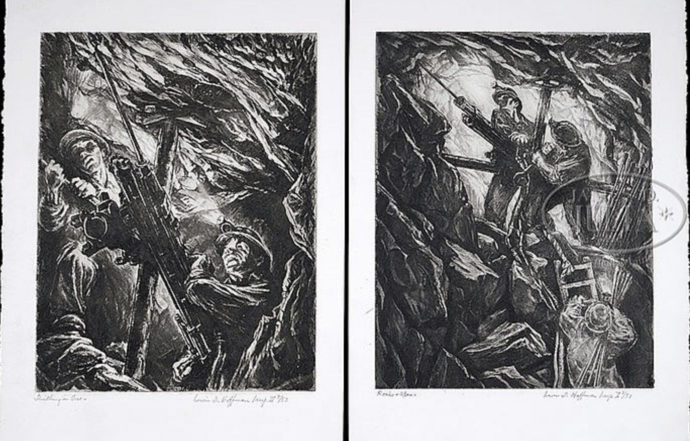

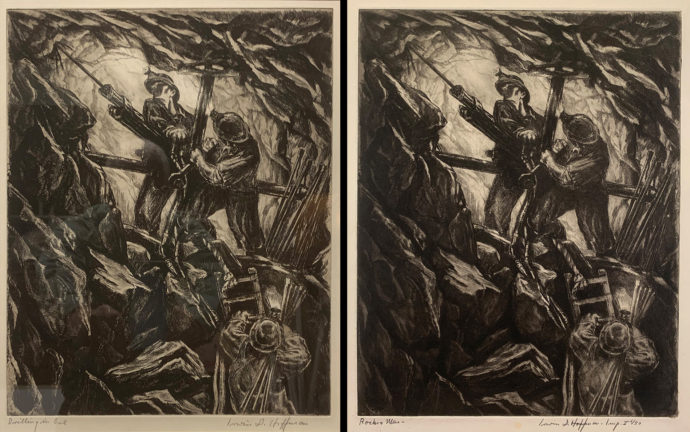

The eBay dealer offered two impressions of a Hoffman etching, 1937-8, 13 7/8″ x 10 3/4″. The one on the left is entitled “Drilling in Ore,” and the one on the right is “Rocks & Men.”

The eBay seller offered both of these prints. I directed the fellow collector to purchase Drilling in Ore–the one on the left–over the other entitled Rocks & Men because Hoffman indicated that that one was from the second edition. He printed “II 6/50” beside his signature.

The Boston exhibition book separately lists a 1937-8 etching called Drilling in Ore, 13 7/8″ x 10 9/16″, and another 1937-8 etching called Rocks and Men, 13 7/8″ x 10 5/8. The plate sizes are nearly identical. When I checked auction records, I found several copies of a Hoffman etching that was obviously a contemporary of the etchings above. And these etchings were titled Drilling in Ore (right) and carried the dimensions: 13 3/4″ x 10 3/4″–good enough match for the Drilling in Ore in the Boston book.

And to cement the issue, at a listing for a James Julia 2014 auction came this pair of images (just below the Drilling in Ore image). Hoffman marked both second edition. He probably titled and signed them at the same time. Drilling in Ore is the title on the left, and Rocks & Men is the tile on the right.

Anyway, here’s the fun part. The collector drops by. He views on eBay the two impressions of the Hoffman mining scene and agrees to buy first edition impression. So I negotiate a price for The Stoker and the print marked Drilling in Ore. When the package arrives, however, the dealer sent the second edition copy marked Rocks & Men. So I complained, and to my surprise not only did the seller agree to send the other but added that I need not return the Drilling in Ore one. So I kept the Drilling in Ore one and, as a thank you, bought two reference books from the seller, including the Boston Public Library book.

I got to compare the two impressions before the collector arrived. I much preferred the second edition one. In printing that one Hoffman wiped the plate leaving a thin veil of ink over much of the plate except around the two workers above. For me this better focuses the eye on the action and better represents the illumination of the scene. It also makes the print seem three dimensional–your eye moves deep into the space where the top workers are. Yet, when the collector arrived, I withheld my preference. He chose the brighter cleanly-wiped impression marked Drilling in Ore.

In the Boston book Hoffman said of Drilling in Ore (that’s the closeup image): “This was up at Noranda mine in Canada. It was a great copper mine. I went down every morning for two months and sketched in preparation for the murals I did for the San Francisco World’s Fair in 1938 which eventually were given to the Colorado School of Mining at Golden, Colorado.”

Hitchings in his comments in the Boston book said of Drilling in Ore: “Hoffman’s etching of scenes in the mines are very rich in color and complex in technique. They have strength of light and dark and strength of design.”

Looking at print dealer offerings, it appears second-edition impressions of Hoffman prints–particularly those of white working men–are not priced less compared to first-edition impressions. Cederholm in her Boston book essay wrote that after World War II Hoffman “kept this printing press active” at a friend’s Vermont farm. She wrote that in the 1970s Hoffman purchased a Woodstock, VT, property from the widow of Rockwell Kent. He upgraded Kent’s studio, and she wrote: “In this workshop also stands the massive etching press to which Mr. Hoffman has recently returned with renewed enthusiasm….”

I suspect Hoffman printed his second editions after moving to the Woodstock property.

Hoffman: a liberal not a communist

Hoffman’s recurring interest in in the life of common folks and of working people in particular was shared by a host of other American printmakers from the 1920s through to the 1940s, a period that included the Great Depression. My collection has myriad examples. In his brief comments in One Hundred American Jewish Artists, Hoffman states: “My chief aim is to express my fellow man with dignity and understanding and with as much perfection as I can command.”

Margaret Sullivan in the AAA book said: “Hoffman’s primary artistic purpose is to depict the people closest to the soil–the toiling laborers, the undernourished and underprivileged, the humble worker nearest to the elemental forces of life…. This objective Hoffman attained without benefit of the ideological preconceptions or sociological propaganda. His intuitive sympathies led him long ago to select this material for artistic expression. Never does his work take on the cast of political agitation….”

While Hoffman’s sympathies were very much with the common, working man he brooked no patience with American artists who were Communists. In 1929 he traveled to Russia with his mother. Sullivan in her essay wrote: “It was an emotional and shocking trip for them both. For two months Hoffman traveled the countryside, meeting distant relatives, visiting small villages, cruising up and down the somber Volga River, looking, listening, and sketching furtively, usually at night.” In his essay in the same book, Hoffman wrote:

“Russia was the biggest fraud and lie in history–I think, in all civilization. All people were beaten down and miserable. You couldn’t sketch anybody; it was forbidden. But on the Volga boat, going down the Volga… I saw the real results of Communism. Peasants would come aboard at each village, you know, and try the next town. They would huddle with their few belongings … it was so pathetic. Their conditions were so terrible, beyond belief. At night while they slept I sketched them in their misery. When the sketches were published in the New York Evening Post, in 1930, they revealed for the first time the true conditions of the peasants. As a result, I was attacked by the Daily Worker and was accused of being an enemy of the people. Many painters in New York were enthusiastic Communists–and there were very many in those days who became my sworn enemies.”

In the 1947 book One Hundred American Jewish Artists, Hoffman also expressed distain for the art world in general:

It would be strange indeed if the confusion that fills the world today should not affect the world of art. The public, art critics and museum directors seem to be in a perfect frenzy to discover the latest in the bizarre and sensational. What a curious thing it is that while only works of art out of the past have survived because of their great beauty, dignity, and fine craftsmanship, today any cheap idea, no matter how badly done, is hailed as worthy of praise of only it is novel. Consequently artists today find it difficult to retain their balance, and many on seeing their serious work ignored, cast aside their integrity and try to become ‘modern.’ “

Needless to say, Hoffman didn’t try to become “modern.”

Comments

Your thoughts are most welcome. Please send them to me at : p1m1@comcast.net

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/irwin-hoffman-etcher-of-workers/trackback/