big clock: buy first, research later

INTRODUCTION

Tall clock, Baltimore, c. 1828, works by Samual Steele, private collection (Fig 169, Gregory R. Weidman and Jennifer F. Goldsborough, “Classical Maryland, 1815-1845,” Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, 1993)

I’ve been eyeing tall clocks (“grandfather clocks” in today’s vernacular) for quite some time. The problems were that: 1) they were quite expensive and 2) clocks made after 1820 (to match the production time of most of my furniture, 1815-1835) were rather scarce. They were expensive because a fine tall clock needed to be a fine piece of furniture making and have a finely made movement (hopefully with a maker’s name on the dial). They were expensive, luxury items in their day as well. Once small, far cheaper shelf and wall clocks started being made in the early 19th century, tall clock production declined precipitously. So surviving well-made tall clocks from the 1820s-on were scarce.

RIGHT: Simon Willard-labeled clock with Stephen Badlam attributed case, c. 1790. (Skinner photo), and LEFT: Josiah Smith-labled clock, Berks County, PA, c. 1820 (Adams Brown Co. photo)

Optimally, the clock I sought would look like this Baltimore one (top). Its triangular pediment reflects the late Federal interests in incorporating accurate design elements from ancient Greece and Rome into American architecture and furniture. It wouldn’t have either of the two most common pediments for tall clocks from the early Federal period (1780-1815): the arch top with a pierced fret on Boston-area clocks or the broken arch pediment common in the Mid-Atlantic States.

No wonder I immediately gravitated to an 1820s tall clock that I came across in Kelly Kinzle’s booth at Delaware Antiques Show last November in Wilmington. Even at what I thought was a very reasonable asking price–$12,500–it would be the second most costly piece of furniture in my house. And it would require an action that I had never done in order to make a purchase: take funds from my investments–a step I would partly come to rue a month later.

RESEARCH

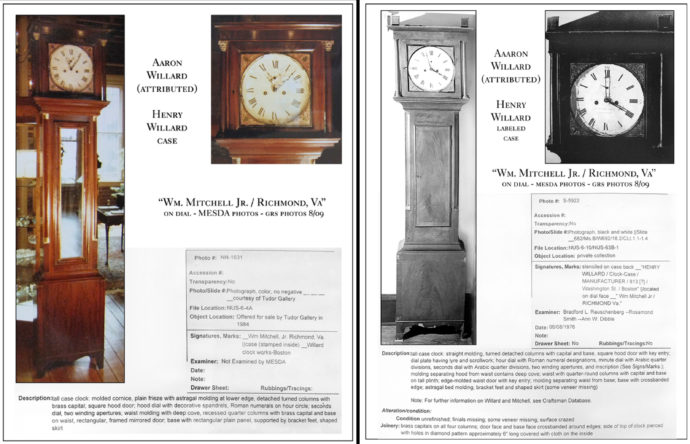

Tall clock, c. 1825, “William Mitchell, Jr. / Richmond, Va” label, movement attributed to Aaron Willard or Aaron Willard, Jr., case bears the stenciled label of Henry Willard. Dimensions: Overall height with center finial: 96 3/4”; Width 21 3/4”; Depth 10”. (Scott Ponemone photos)

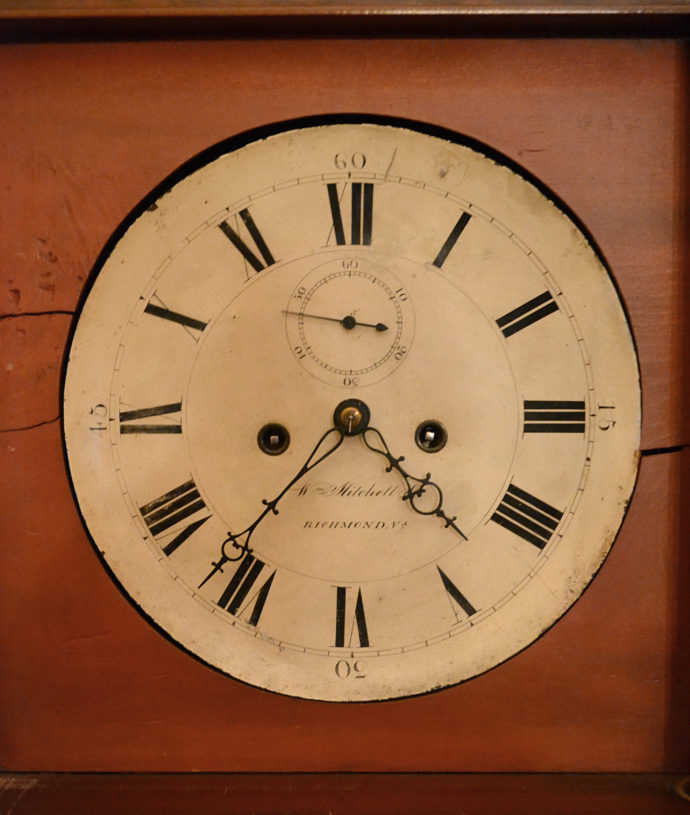

Pretty striking clock, no? Finely proportioned case, fine use of mahogany veneers, and that triangular pediment. But even better was its pedigree. While its dial clearly read “Wm. Mitchell Jr., Richmond, Va,” its case bore the stenciled label of Henry Willard and the dish-shaped dial with églomisé (reverse painted) spandrels shouted Aaron Willard or his son, Aaron Jr.

After a few words with Kinzle, my husband Michael and I left to explore the rest of the show. Several temptations later, we returned. Kinzle assured me that the pediment was original, although the finials, while of the period, were probably replacements. In a few minutes he agreed to my $10,000 offer, and I had a clock that he would deliver and set up in a week or so.

Once I got home, I immediately turned on the computer. What would a search for “Mitchell Willard clock” turn up? I didn’t expect BINGO immediately, but there in the image search was my clock. The web page holding that photo was a “sold” listing on the Gary Sullivan Antiques website (https://www.garysullivanantiques.com/). Sullivan’s lengthy description begins:

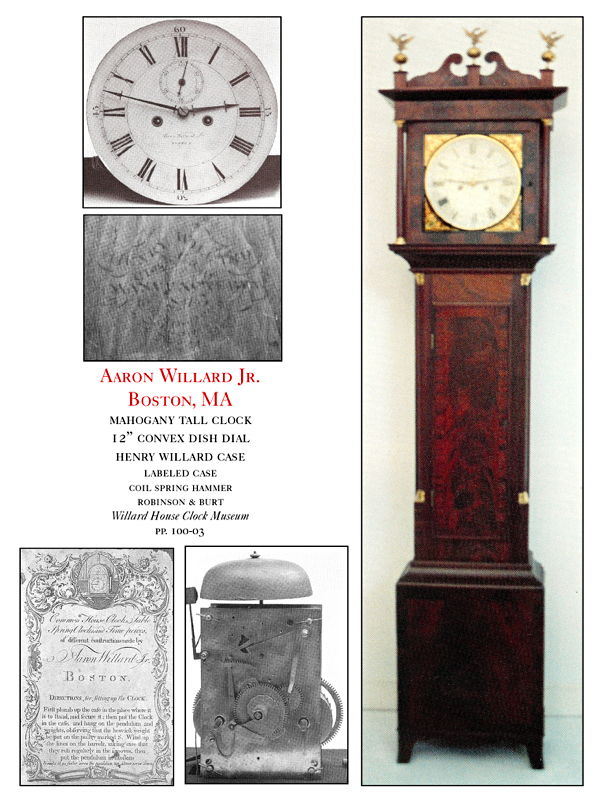

This Classical tall case clock is an extremely rare form with a dish dial. Less than a dozen of these clocks have been documented and about half of those are signed for retailers from Virginia and the Carolinas. The clock and case were produced in Boston by either Aaron Willard [1757-1844] or his son Aaron Junior [1783-1864] during the first quarter of the 19th Century. These distinctive cases typically bear the stencil of Aaron’s cabinetmaker son, Henry Willard [1802-1887].

Well that made me feel good. Then when I scrolled further down on my web search, I came across a listing from the Christie’s auction house in New York. Here’s the link. It turns out my clock was Lot 678 of Christie’s sale on January 20, 2017. Estimated from $8,000 to $12,000, it sold for $6,875. (That price is a combination of the hammer price of $5,500 and the 25% buyer’s premium of $1,375.)

Aaron Willard made shelf clocks that had features in common with the tall clocks in this blog post: the dish dial and the églomisé painting with lyres on the dial glass. These common features were part of the reason my clock’s movement was attributed to Aaron Willard or his son. (These images are from a 2010 catalog listing by the Skinner auction firm.)

Did Sullivan purchase it at auction at Christie’s in January 2016 and then sell it to Kinzle? Or did Sullivan put it up for auction and Kinzle was the buyer at Christie’s? But further scanning Sullivan’s website led me to believe the latter. Sullivan has posted a short video from his installation at the 2015 Delaware Antiques Show. It’s opening view clearly shows Sullivan discussing my clock with a woman. (Click here to find the link on Sullivan’s website.) When Kinzle delivered the clock, he confirmed that he was the purchaser at Christie’s.

Another video on Sullivan’s website answered another question of mine: How unusual was it for a Northern tall clock to be retailed in the South? It turns out that Sullivan addressed this issue during a lecture/slide presentation at the 2012 furniture forum at the Winterthur Museum & Country Estate. His talk was called “Clocks for Corn: Yankee clockmakers trading with the South.” (On Sullivan’s Instructional Videos page, a link to a video of his talk can be found. Here’s the link.)

In his description of my clock, Sullivan discussed the man whose name appears on the dial:

William Mitchell Jr. was born in Boston trained as a silversmith. He is known to have worked in Richmond from 1818 to 1845. He was initially in partnership with Elisha Taft from 1818 to 1820 under the firm Taft & Mitchell before establishing his own silversmith business that he grew to be largest in Virginia. Mitchell retailed a large range of products including both clocks and watches. He retired in 1845 and sold the business to his younger brother Samuel and John Tyler who continued under the name Mitchell & Tyler.

Between Sullivan and Kinzle, I realized, was quite a wealth of knowledge about the production and selling of tall clocks in the 1820s and the selling of tall clocks today. Fortunately when I asked both men whether they would like to be interviewed for my blog, both agreed. The following are transcriptions of interviews I recorded with them.

INTERVIEW WITH GARY SULLIVAN

The first thing to say about Gary Sullivan is that he has written extensively on American clockmaking. For instance, he co-authored with Brock Jobe and Jack O’Brien Harbor and Home: Furniture of Southeastern Massachusetts, 1710–1850 (Hanover, N.H., and London: University Press of New England, 2009). The book’s jacket blurb sums it up succinctly: “Gary R. Sullivan, president of Gary R. Sullivan. Inc., is a nationally recognized expert on early American clocks.” (A bibliography of his writings appears at the end of this post.) Harbor and Home was the catalog for an exhibition of the same name at Winterthur in 2009.

I begin the interview by asking him about his research into Yankee clocks for buyers in the South. And since my Mitchell/Willard clock was not mentioned in his 2012 Winterthur lecture, I asked him when and how did it enter his inventory.

When did you first become interested in this phenomenon of Northern clocks made for Southern clients?

Around 2007 or 2008 when I was working on a study of Southeastern Massachusetts furniture for a Winterthur museum exhibition called “Harbor & Home: Furniture of Southeastern Massachusetts, 1710-1850.” I wrote the chapter on clockmaking for the book. One of the principal characters in Southeastern Massachusetts clockmaking was John Bailey Jr. He and his family were the most significant clock-making family in the region. And I discovered that some of his clocks seemed to wind up in the South, and in fact I discovered that a couple of them had presentations on their dials. They were inscribed with the names of the original purchasers. For example, one was inscribed, “warranted for Joseph G. Ray,” a southern merchant, and it just didn’t make any sense to me. So I started digging and looking for information about John Bailey and what his connection was with the South. I found some fantastic letters at the Earlham Library [Earlham College, Richmond, IN] between John Bailey, Jr. and the father of an apprentice of his who was in the South. In his letters Bailey said that he was planning to send some clocks to the South to be sold. This was fascinating to me. So I kind of build on that, and I learned more about Bailey and I learned about the clients that bought the clocks. So that’s what got me started.

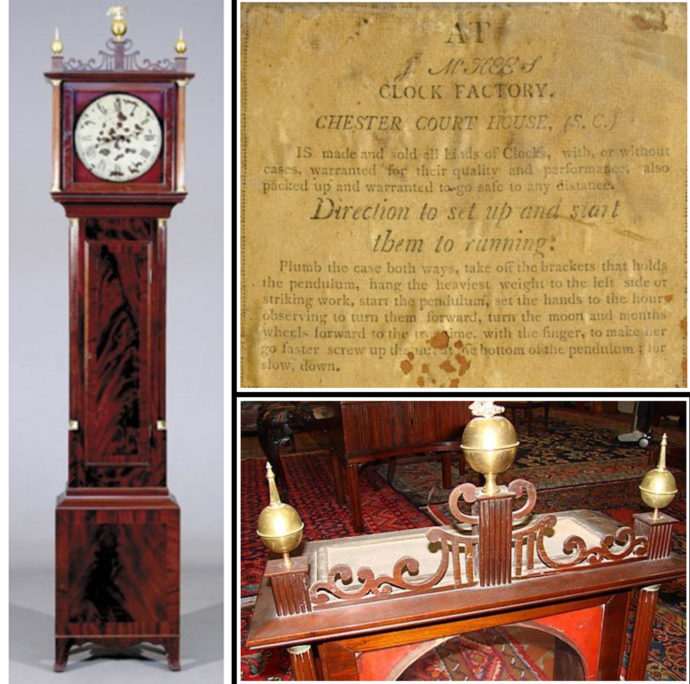

A pair of MESDA listings of Aaron Willard-attributed movements in a Henry Willard case with a dish dial labeled: Wm. Mitchell, Jr. Richmond, Va (Pages provided by Gary Sullivan)

How did you find out that the Willards did something similar?

Early in the process of searching I went down to MESDA [Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-

A labeled Aaron Willard Jr. dish-dial tall clock at the Willard House Clock Museum, Grafton, MA. (Photo supplied by Gary Sullivan)

When did the Willards stop making tall clocks for local consumption?

That would have been 1812 to 15. I would say that by 1815 they were absolutely not making any tall clocks for local consumption. Probably by about 1812. It was strictly the more fashionable and more affordable patent time pieces–banjo clocks.

I did come across tall case clocks with the dish dial that had the Willard name on the dial. Did that indicate they were made for local consumption?

No, not necessarily. I think at least one of the clocks that went to the South had the Willard name on the dial. There’s at least one that’s got a Willard paper label inside, and then some of them have the Henry Willard stamp. So my assumption is that all of those dish-dial clocks were made for export to the South.

Since your 2012 talk at Winterthur–other than the Mitchell/Willard clock that I eventually bought–have you found others that were not listed in that presentation?

In addition to yours I saw photos of another William Mitchell Jr. clock, not in great condition. It had lost it’s églomisé from the door and did not have any type of fret-work on the top, but what was really nice about it is that it included an original bill of sale signed by William Mitchell, Jr. Two things about it were very interesting. One was that it was the date of the sale was 1835, which puts it considerably later than what I was thinking. The other was the price of $75, which seemed like a tremendous amount of money at that time particularly in 1835, where you could buy clocks manufactured in factories very inexpensively. So those two facts were surprising. That’s the only other one that I found since the presentation other than yours.

An églomisé spandrel for my Mitchell/Willard clock. (Scott Ponemone photo)

Each of the églomisé spandrels on my clock has a lyre. Are the spandrels about the same on the other dish dial clocks?

And I haven’t really compared them, but they’re similar. I don’t know that they’re exactly the same. Some are restored, some are not. So it’s hard to say, but they’re very similar.

What’s your opinion about the condition of the spandrels on the clock that I bought?

I think I felt they had some some restoration, but they were basically original.

That’s kind of how I thought about it a too. There is some little bit of painterly quality that doesn’t seem right to it. So how did you come across the Mitchell/Willard clock that I’ve eventually bought?

Someone contacted me who had the clock in their family for as long as they could remember. I ended up purchasing it and had it shipped up. Looking through my e-mail messages, which is where people usually make initial contacts and I couldn’t find anything about it. That tells me that it was all conducted over the phone. The person I bought it from didn’t know any history like whether her parents had collected it at some point or whether it had always been in the family. She didn’t know. So there was no interesting provenance that came with it. And I think it was from Charleston. I’m just going by memory. I’m not sure of that, but I think it was living in Charleston.

What was the condition of the clock when you got it?

Pretty much the same as what it is now except that the finish was in dreadful condition. I had the finish restored.

I saw that there was a repair to the back, toward the base supporting one of the legs, one of the stiles.

Oh yeah, I think we did have that done. I think it was missing part of the foot maybe.

OK. Now I saw one of your videos to the 2015 Delaware Antiques Show, and you’ve had it there.

Yeah we got it right before the show and had hustled to get it ready for the show. There were people who liked it, but we didn’t make a sale.

I See. Now you listed it on your website and you called it a Classical clock. Can you explain why you gave that designation?

Well, you could call it Classical, or you could call it Federal; you could call it late Federal. I thought Classical was a good description for it. It was the tail end of the Federal period. So you could use any one of those terms.

I photographed the reverse side of the classical pediment of my clock to assure myself that it had sufficient oxidation to indicate that it probably was original. The two triangular thin mahogany boards fit into slots on the sides of the three chimneys. Small pieces of wood were inserted into the slots to serve as wedges. (Ponemone photo)

Did the simplified pediment detract buyers?

How do you mean, that this was more simple than a traditional clock fret work?

Yes.

Oh, I don’t think so. This was the latest style in the period when it was made. So clocks with pierced fretwork were out of style, were out of fashion at this point.

In fact that’s what attracted me to the clock. It was you know 1820s modern in the way. It updated the style just enough.

Yes.

So you took it to that 2015 Delaware show. Did you show in any other venues?

I don’t think so. I only do one show a year and I don’t typically bring things to a show twice. I’m sure that’s the only place I showed it.

If you care to, give me a sense of what your asking price was at the time of the 2015 Delaware show?

I don’t remember. I mean I handle hundreds and hundreds of clocks. So it’s hard to distinguish one from another, but it was probably around $20,000.

Well in fairness I’ll say I eventually paid half that exactly .

Right. It’s a great buy. Yeah, I might have had it priced that 19,500 or 20,000, something like that. It’s a great clock. It’s just that there aren’t a lot of buyers who are looking for that.

You know I think the market is better today than it was when you bought it. I think that was kind of a low.

Well, it was just a few months ago.

The market is better today than it was then for clocks.

Well when was the high point for pricing of those clocks?

2006 was the peak of the market for Americana, January 2006.

And the nadir?

I would say fall of 2016, the end of 2016.

Thanks, Gary. I do appreciate your expertise, and now I’m going to go back and read your essay in the book on Southeast Massachusetts furniture.

Kelly Kinzle poses with my clock after he installed it. (Ponemone photo)

INTERVIEW WITH KELLY KINZLE

Kelly Kinzle’s booth at antique shows at the York County Fairgrounds has always been a must-see. The quality and condition of his inventory has never disappointed. He has always presented a few select tall clocks. His prices have been fair but usually above what my wallet could bear. But there have been two exceptions, both fancy early 19th-century seating furniture.

Previous to my purchase of the Mitchell/Willard clock, I had bought the red high-back fancy chair and the cane-seat settee from Kelly Kinzle. The cleaning of the chair was pictured in a December 2016 blog post: “2016: MARBLE PIER TABLE & HIGH-BACK FANCY CHAIR” (Ponemone photos)

When I entered of the 2017 Delaware Antiques Show, naturally I stopped at Kinzle’s booth. After greetings, we discussed the merits of a Federal bookcase that he had. When he turned his attention to other potential customers, my eyes jumped to a late Federal tall clock nearby. It both addressed my search for a distinguished late Federal tall clock and, with a stretch, fell within my price range. So after my husband Michael and I explored the rest of the show, we returned to Kinzle’s booth. This time I asked Kinzle to discuss the clock. I didn’t ask that many questions–unlike my normal procedure–before I made an offer that was quickly accepted. I left a deposit, and Kinzle agreed to deliver and set up the clock. An unlike any previous collecting purchase, I would have to dip into my savings to pay the balance. Part of me was shocked. Michael kept his reservations to himself.

Kelly Kinzle also kindly agreed to be interviewed.

I enjoy your show booths all the time because you always have a nice selection of clocks, tall-case clocks in particular. It must be both a fascination and a certain amount of expertise. Can you tell me a little bit about the first part, the fascination with that type of antique?

Well, I guess the expertise came with the fascination. The first clock I ever bought was probably the worst clock ever bought. But I don’t know what it was that attracted me. Maybe it’s just the mechanical part and the fact that first you get a good piece of cabinet work and then you get a good piece of mechanical work, where a lot of things don’t have that. You can have a chest of drawers or something else like a bracket clock. With a tall-case clock you have a combination of both. Maybe that was the fascination. I never really analyzed it. You’re my first psychic reading.

I’m just trying to help.

Yeah.

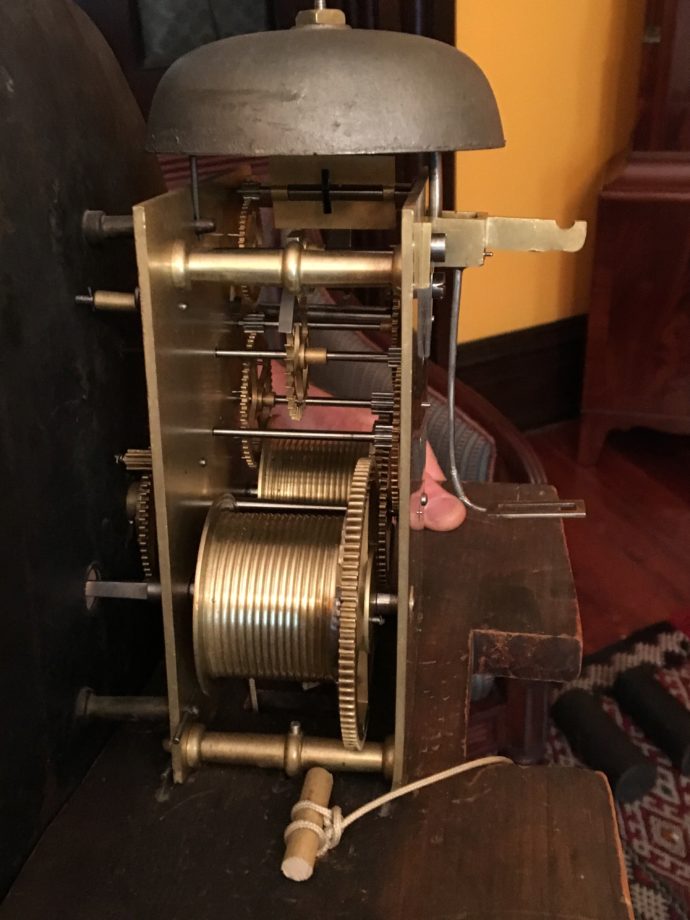

The eight-day brass movement of my clock. I asked Gary Sullivan why he concluded that the Willards made it. He responded: “The attribution is based on the clock being made at the Willard compound (Henry Willard worked on the same premises as Aaron Sr. & Jr.) The movements are pretty generic, with no earmarks to look for. (Ponemone photo)

What’s the market for tall-case clocks these days?

It just depends on the clock. I just sold a really good clock. In fact I’m delivering next week. You know it’s not as frantic as it was. In my heyday selling clocks I sold 50 American tall-case clocks a year to very few buyers, mostly all dealers. I didn’t have to worry about getting them working or making sure the finish was good or anything else. I constantly had wholesale customers that were either collectors or dealers that were constantly buying. Unfortunately all of those people either retired or died. So the market for me went into getting them fixed and selling them at a slower pace.

More of a retail market?

Sure, where before I didn’t have to worry if they worked or whether the weights were there or anything else, I just bought them and sold them. It was great wholesale market.

What type of clocks did retail customers gravitate toward?

The same thing. I mostly buy and sell regional clocks of this area–Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia. I don’t buy a whole lot of New England clocks. I just buy what I find.

Well what attracted you to bid on this Mitchell/Willard clock in New York (Christie’s)?

The Richmond connection. There’s one in the Dixie clock book [James W. Gibbs, Dixie Clockmakers, Pelican Publishing Company, Gretna, LA, 1979], and I always admired that. So when I saw it in New York, I thought that it was a nice clock and a great find.

Did you know it was a deaccessioned by Gary Sullivan?

No, I didn’t know that was his clock.

Did you need to make any repairs to the clock after you bought it?

I didn’t do a thing to it.

Did you show it at any show previous to last fall’s Delaware show?

Probably, I can’t imagine that I didn’t take it somewhere. I’m trying to think when I bought it.

Well, it was bought in January of this past year.

OK, then I would have probably taken it taken to York. I might have taken it to York. I didn’t take it to Philadelphia. So I guess York was it.

When you open up the reverse-painted dial glass, you find that the dish dial is surrounded with red-painted wood. The hands are made of scrolled cut steel. (Ponemone photo)

Did you get any comments (at the Delaware show) before I’d made my purchase?

No, not offhand. Not that I recall. I mean if you’re sitting in a booth with 50 objects and 10 people are walking by, saying things about 10 things every five minutes. It’s hard to catch them all and even keep them in your thought process.

Yeah, I guess so I’ve never been in your position. Is there anything about that clock–it’s Classical look–that strikes you as either different or not what people are looking for?

The unique things about that clock was that that clock was at the end of the [tall-case] clock-making period. When spring clocks became common and popular, tall-case clock-makers went out of business basically. That’s the very end of the period.

The clocks that I find fascinating are the true Empire, really restrained Empire clocks. I’m not talking about having half columns or anything. [I’m talking about] really refined ones without the traditional broken-arch top or, for New England, the arched tops with the pierced fret. When you move out of that, there are very, very few clocks made. So when you find someone that was still making them, like with the dish dial, that was the exception. You didn’t find any other clocks with the dish dial. That was a carryover from the shelf clock. And it was the shelf clock was what put the tall-case clock out of business. You didn’t need all of that room to get an eight-day movement.

What attracted me to the clock was because of my fascination–my affordable window I should say when I started getting more serious and collecting–was in the late teens, to the 1820s and sometimes into the 1830s. So that there’s not much clockwise that’s really available from that time.

I know. Some command a huge price. A number of years ago I sold a clock out in the same period, a Baltimore clock, for $54,000. One particular customer friend gave me a photograph of a clock and said, if you ever find this clock, I want to buy it. And of course it took me 20 years to find one, and I found it. But then he was going through a divorce and couldn’t buy it. And I ended up selling to a guy in Alexandria for I think $54,000. And it was just a simple, plain mahogany clock in that 1830s period.

Well, that kind of covers the subject. I think I was kind of lucky, being in the right place at the right time.

Like you said, the right timing on that clock was everything. I imagine in a couple of years things are going to be cranked up price wise again and it’s not going to be obtainable.

The case of my clock bears the stenciled label of Henry Willard, one of Aaron Willard’s sons. While he did make clock movements, Henry was known as a clock case maker. In his website description of the Mitchell/Willard clock, Gary Sullivan wrote: “The sides of the hood have a field of circular holes arranged in a diamond pattern. This detail is a distinctive feature found on tall clocks and shelf clocks produced by Henry Willard and is considered a signature treatment.” (Ponemone photos)

ADDENDUM A: other dish-dial tall clocks

I found two other Willard-made dish-dial clocks via online searches, and another appeared in a book in my reference library.

These images came from the Charlton Hall website. This auction house is located in West Columbia, SC. Besides severely worn paint on its dial, the clock is missing its hood glass with its églomisé spandrels, The frets may not be original.

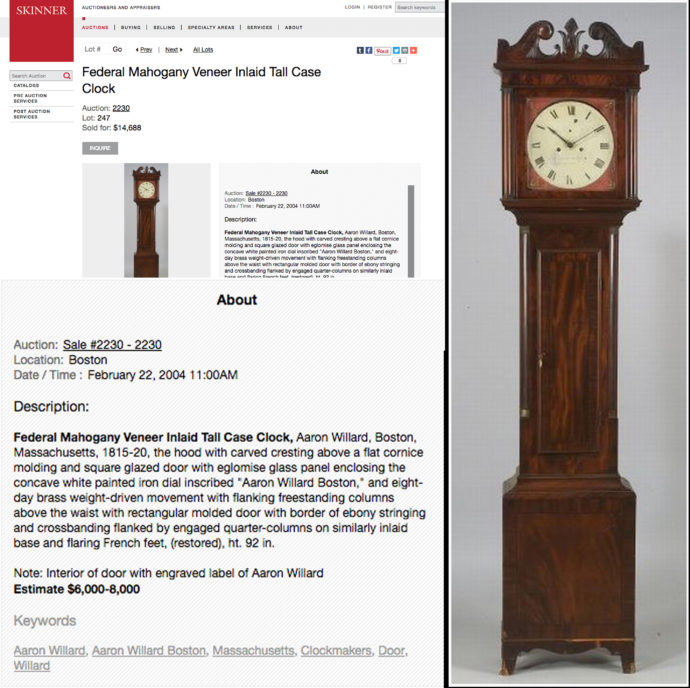

Above is composite of a page from the Skinner Auctioneers and Appraisers website. It shows a dish-dial Willard labeled clock with a broken-arch pediment that sold for $14,688 in 2004.

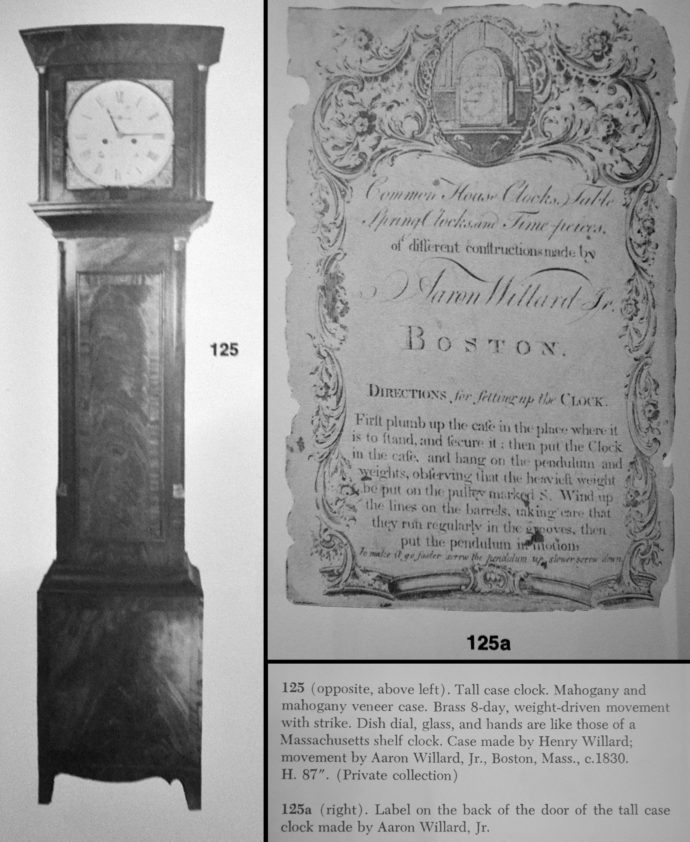

I found the above listing of a Willard dish-dial tall clock in The American Clock by William H. Distin and Robert Bishop (Bonanza Books, New York, 1976).

ADDENDUM B: Rue the day?

Almost a month after the Mitchell/Willard clock purchase, I needed to make another major withdrawal from my savings. On the season’s first snowfall, my 2005 Mazda 3 lost traction on an interstate overpass. I spun into a cement wall and did just enough damage to have the car designated a total loss. Ergo, I bought a new Mazda 3. On the bright side, 13 years has made a lot of improvements to the model with little or no price inflation. On the down side, I need to remind myself that my investments are not a bank for my collecting addiction.

GARY SULLIVAN BIBIOGRAPHY

Books

-

- Musical Clocks of Early America, 1730-1830, By Gary R. Sullivan and Kate Van Winkle Keller: Willard House & Clock Museum, 2017

-

- The Music of Early American Clocks, 1730-1830, by Kate Van Winkle Keller and Gary R. Sullivan: Willard House & Clock Museum, 2017

-

- Art & Industry in Early America: Rhode Island Furniture, by Patricia E. Kane, Dennis Carr, Nancy Goyne Evans, Jennifer N. Johnson, and Gary R. Sullivan: Yale University Art Gallery, 2016. (Winner of the 2017 Historic New England Book Prize and winner of the 2017 Charles F. Montgomery Prize)

- Harbor & Home: Furniture of Southeastern Massachusetts, 1710–1850, by Brock Jobe, Gary R. Sullivan and Jack O’Brien: Winterthur Museum, 2009. (Winner of the 2010 Historic New England Book Prize)

Other Publications

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/big-clock-buy-first-research-later/trackback/