Trophies

The National Gallery of Art has had some splendid big-name summer shows. One on the American George Bellows (through Oct. 8); another on the Spaniard Joan Miró that just closed. But I’d like to draw your attention to a more modest affair: one devoted to the 17th-century Dutch artist Willem van Aelst. He pictured a world that sat on a tabletop or, to be more accurate, that he arranged on a tabletop. Sometimes his still-lifes were animated by mice and bugs. Many times his animals were the trophies of the hunt, hanging bloodied and limp. Sometimes his focus was on bouquets of the finest flowers. Oftentimes glass and silver and steel weapons and lustrous fabrics completed the mix of surfaces and textures. If one word can sum up his painterly achievements, it would be: Bravura.

Willem van Aelst

Dutch, 1626 – 1683

Still Life with Dead Game

1661, oil on canvas

Dimensions overall: 84.7 x 67.3 cm (33 3/8 x 26 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art,

Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund

Accession No. 1982.36.1

To quote the National Gallery exhibition blurb: “Bringing together 28 of these sumptuous paintings and his only known drawing, this exhibition—the first devoted solely to this artist—celebrates the most technically brilliant Dutch still-life painter of his time.” His reputation grew as he sought clients first in Paris, then in Florence, where, to again quote the National Gallery, “he became a favorite at the Medici court.” On his return to his homeland, he continued to garner illustrious patronage. He was a showman and he knew how to please. His paintings can dazzle, I agree. Yet I found myself more drawn to the modest youthful canvases and the reflective canvases of his later years. They seemed more personal, certainly less bombastic.

The notion of displaying paintings of animals newly slaughtered and destined for the dinner table is not in vogue right now. Damien Hurst’s preserved sharks and cattle are not really on the same playing field. But nature morte has certainly been a topic of great longevity. Our own mortality is on display when we view animals that die to nourish us. I must have been smitten with the idea when, as an employee of Afro-American Newspaper in the early 1970s, I asked the paper’s artist Tommy Stockett to paint a picture of a newly killed chicken. I was under the influence of the late 19th-century trompe l’oeil paintings by American artists like William Harnett and John Peto. In return, I’m embarrassed to say, I made a watercolor copy of a sailboat photograph. I sure got the better part of the bargain.

Thomas Stockett

(American) 1924-2007

Untitled

Acrylic on paper, c. 1973

16 3/4″ x 12 1/2″

Later in the 1970s I became an habitue of the Harris Auction Gallery on Howard Street in Baltimore. I didn’t know what I was bidding on. Yet as a collector-want-to-be, I certainly had dumb luck. One evening I spent $10 apiece for six hand-colored lithographs, four by Edouard Travies, two by A. Adam.

A. Adam

(French)

Pinson Lievre, Perdrix Rouge

Early 19th century, from Etude de Nature Morte, hand-colored lithograph, c. 1840-50, 26” x 18 1/2”

Edouard Travies

(French) 1809 – 1869

La perdrix rouge

hand-colored lithograph,1860s, 20 1/4” x 14 1/4”

In the mid-1980s, with about seven or eight years under my belt as a collection of mostly American prints of the 1920s through early 1950s, I made two trips to England. There I sought out English wood engravings (a passion of mine) of the same period. Among my trip trophies was an Iain Macnab. At least in the land of the hunt the nature morte tradition was alive and well in the 20th century.

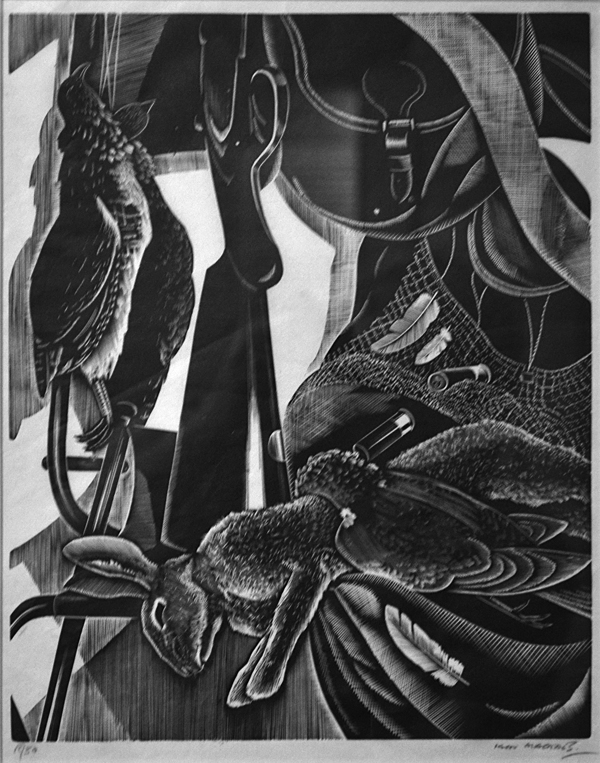

Iain Macnab

(British) 1890 – 1967

Untitled

Wood engraving, 1930, 10 3/8” x 8 3/8”

Signed and dated in pencil

Did I take up the challenge of trophy death? Well, I did do chicken paintings. But they were alive and colorful and competitive. They were miniature show chickens, cradled by their handlers waiting their turn before the judges.

Chicken Littles

Watercolor on paper, 19 Jan. 2012

8″ x 32″

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/trophies/trackback/

Thank you for sharing the blog with me- the overall presentation, and the quality of photography, is beautiful! And NOW I get how the ‘stream of thought’ approach holds together…

Next time we’re wandering around the house, I’d love to see the English lithograph in person- it looks like somebody was a little bit influenced by German Expressionist cinematography….