Rosemary Feit Covey: Printmaker’s Journey

This article first appeared in the Fall 2014 issue of the Newsletter of the Print Drawing & Photography Society of the Baltimore Museum of Art. This blog post enables me to offer color imagery as well as additional images.

Introduction

Thanks to an exhibition this spring at Evergreen Museum & Library, curated by James Archer Abbott, its Director and Curator, I finally got to meet artist Rosemary Feit Covey. You would think that with my longstanding interest in wood engraving, with my first seeing her work some 30 years ago, and with her studio just down the road at Alexandria’s Torpedo Factory, I would have made an effort to meet her long ago. But I didn’t. I offer no excuses. At least I didn’t let this opportunity slip by.

I went to the exhibition opening expecting to see a sequence of individually framed wood engravings. Was I ever wrong. Yes, there were several pieces just how I expected. But Rosemary’s expressions as a printmaker were not limited to traditionally presented relief prints. There were painted-over collages of prints. There were strips of prints made to look to like hanging lengths of film housed in a light box. And there was an installation involving drawings multiplied by photocopying.

How did the wood engraver whose images I first saw decades ago become such a multidimensional artist? This is what I wanted to know when I sent her a sequence of questions. Here are her answers:

Interview

Could you give a brief account of your childhood and when you started thinking of yourself as a visually creative person?

I have no memory of a time before I made things. My grandmother on my father’s side, a transplant to South Africa from Vienna, was my soulmate from birth. She had big boxes of fabric scraps. She made my clothes, and I made my dolls’ clothes. She taught my sister and me to embroider and crotchet, and she never used a pattern. My nursery school teacher told my mother I was talented. My mother was surprised. The teacher then showed her what the other kids were doing. My first memory of working on my own on paper was a pastel I made of the abandoned gold mine dumps outside Johannesburg. I drew them teeming with miners.

I lived in a fantasy world of my own creation much of my childhood. The days home sick, which I coveted, were my real education. My room was my sanctuary. With parents warring endlessly outside the door, I drew and read and played complex games with dolls.

< Photo by Rusty Kennedy

I first saw your work some 30 years ago. These were wood engravings. Did you think of yourself primarily as a wood engraver? Who influenced you to practice wood engraving?

I was taught wood engraving in three days by Barry Moser, my high school art teacher and now a famous wood engraver/illustrator. I had studied printmaking at Cornell and MICA. Afterwards [while living in D.C.] I went up to New England for a few days with Barry, and he gave me basic pointers. Those few days were not followed by any other formal engraving training. I figured it out on my own. I like the quote: “Wood engraving is the easiest to learn and the hardest to master of the printmaking techniques.” I’m not sure who said it, but I think it is true.

I liked the enforced concentration of engraving, pulling lightness from the dark on a block of beautiful but unmalleable wood. It was all a means to convey emotion. I never have felt any form of wood engraving fetishism, but I did feel an immediate knowledge from my first engraving that I had found my path artistically. My grounding in the prints of the past, Dürer, Hogarth, the WPA artists—studied from childhood—gave me a high bar to aim for. With the exception of one Doré image (done to teach myself technique), I never tried to copy or approximate any other artist. I also gravitated towards line work. The lack of color seemed more connected to dreams and internal landscapes. None of this was an intellectual decision. It all came out of just doing.

I had to make a living, not easy doing something so esoteric. So I did lots of commissions for years: Christmas cards, baby announcements, book illustrations. In most of these I had to curb my natural tendency towards the macabre. I remember the Musical Heritage Society chairman pleading that I not do a sad looking Christmas and Easter for their magazine cover. None the less, glimmers of my natural tendency to go in this direction would slip in even to these benign subjects.

What was it about wood engraving in either production process or as a finished product that made it the right medium for you?

The act of carving—the struggle to deal with the nature of wood—is very different from drawing. (Fig. 1) The concentration needed and the difficulty of showing facial expression or skin tone as one carves it all in reverse, somehow draws from a deeper reserve than painting can. Now that I am older I appreciate the freedom of a quickly drawn line and endless chances to get it right. But when I was younger, my soul resonated only while I engraved. It pulled something deeply felt to the surface. The need to get this out forced me to develop some skills in doing so. It was a hunger and need to find expression.

Fig. 1 Rosemary Feit Covey in her Topedo Factory (Alexandria VA) studio demonstrates how she cuts a block. (Photo by Scott Ponemone) >

What subject matter attracted you initially? And how did you represent that in your images? Can you offer particular prints as examples?

I have always tried to convey an internal life and not shy away from difficult emotions. I’ve tried to create pictures that could be real but actually are about something else. For example, I did the print based on my childhood in South Africa. I was at a swimming pool one day. A black man walked passed, doing nothing more than walking in front of me to the water, but I protectively placed my kick board in front of my body. It was a knee-jerk reaction. I was horrified and confused that I had done this. So I explored the emotion and found the link back to my childhood in Apartheid South Africa where fear and sexual tension were conveyed even to an innocent child. The remnants of this training sadly still remained in my unconscious—not a pleasant thing to face. So I created the image about that—a difficult subject. At the same time the print can be viewed as a slice of life genre piece, if the viewer wishes it.

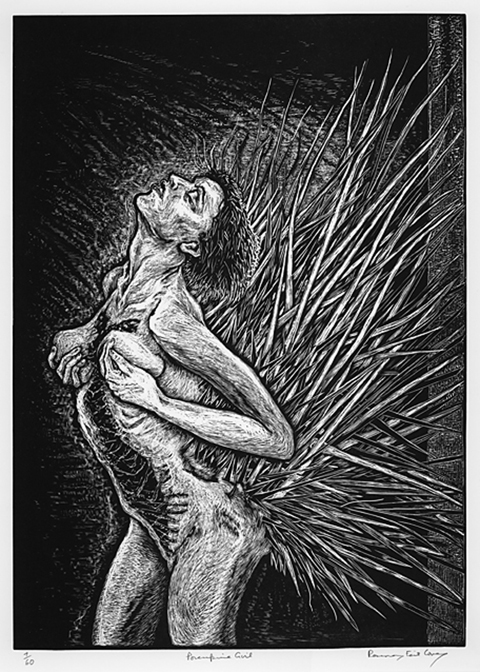

In a later work called Porcupine Girl (Standing) (Fig. 2), the message is about the strange nature of pleasure and pain often connecting. Just having gone through life-threatening emergency surgery, I flew to Italy for a Rockefeller Fellowship on Lake Como—one of the scariest and happiest times of my life butting up on each other and making for a strange intensity. Hopefully if the work is honest, it will resonate with others, but I do not worry about others. For me it’s just about getting it all down. David, a guy who hired me to chronicle artistically his brain tumor experiences over three years, certainly believed this to be true. He wanted to use himself as a model of a specific case that could move beyond his death.

< Fig. 2

Porcupine Girl (Standing)

1999

wood engraving

14″ x 10″

Ed. 60

photo by Eric L. Mackenzie

How did your imagery evolve (as a formal printmaker)? What topics became important to you and why? Can you also offer me particular examples?

As one gets older the neurosis of childhood recedes and larger issues become artistically interesting. But usually ideas still start with the personal. I have now done large installations which have no genre elements. The most recent is on non-culpable guilt called Red Handed (Fig. 3), a subject that consumes me. By non-culpable I mean guilt at a remove. For example, in the case, as documented, of the children and grandchildren of Nazis commandants, they feel guilt but bear no personal responsibility. Or true stories of car accidents where passengers or pedestrians are killed but it was not the driver’s fault, how does one live with these things? In my artist’s statement I tried hard to link this to societal responsibility, but really it is about personal situations. If the personal is removed, nothing is felt. I have my own reasons why this subject resonates. Art has to come from something real, or why do it? Anyway, why one does it is a whole other issue with possibly no answer.

As with most artists my themes reappear through my work in different forms over time. For example, the light boxes in the Evergreen show are again on how pleasure and pain can mesh. (Fig. 4) This time the story is based on an actual couple’s relationship. Starting as a commission it grew into a large project that stretched my ideas about wood engraving, marriage and storytelling. I wanted the hand-pulled prints to look like film noir strips of photographs hanging to dry. I used wax and light boxes to convey the feeling. I was helped by Director Andrea Harris of Grand Central Art Center in Santa Ana, CA. She gave me a residency and encouraged me to try something really different. When I mentioned light boxes, she ran down to the art center’s basement and produced a couple of them.

Eventually they were custom designed, and it took two years of work to create the final project.

Fig 3 Rosemary painting Red Handed. (Photo by Graham Scott)

Fig 4 Light Box is composed of wood engravings printed on vertical lengths of paper and makes reference to rolls of film hanging to dry. To enhance this effect Rosemary backlit this piece. BELOW A closeup of one of her Light Box pieces. (Photos by Graham Scott)

At Evergreen, formal, individually framed wood engravings are in the minority. Can you talk about your other means of presentation: when and how they came about, technical hurdles needed for each?

Small wood engravings began to look dated to me as the world changed. I was stretching for more ways to convey ideas as a printmaker. This happened organically, not in a bolt.

I had rubbed my prints and was throwing on the floor large sheets with multiple images as I corrected my prints. They had some faces printed over and over, and soft and hard printings all put together. These I usually threw away, but my husband loved them and kept some. From his interest began to emerge a new way of working. I used my blocks as a library of images and combined parts of them into new complex works printed on one sheet. The Dark Backward is the best example of how this looked. In Santa Ana I had created a large image on Tyvek. The Arlington (VA) Art Center awarded me a chance to print this to wrap around a huge building—total dimensions: 15 feet x 300 feet. (Fig. 5) It was again a new way of thinking about printmaking. I used large commercial printers and found this just as challenging and requiring just as much trial and error as hand rubbing. Now I use a mixture of commercial printers and my Vandercook proofing press to create images that combine prints from both sources. I continue to create additions to my library of images and often work in parts, carving multiple blocks for each one-of-a-kind piece. I am still very much a printmaker but also a painter. I hate the word “collage,” maybe associating it to decoupage, but I guess I will have to live with it.

Fig. 5 The O Project, 2007, Arlington (VA) Arts Center, Dupont ™ Tyrek ® banner, 15′ x 300′. (Photo by Rosemary Feit Covey) BELOW Closeup of the banner. (Photo by Doug Sanford)

The columns (Fig. 6) are again a new means of using printed images to create a forest of forms—sculpture from prints. These were created for the Evergreen exhibition as an installation. There are nine of them and they range in height from seven to ten feet.

Fig. 6 Rosemary’s columns standing in the main hall of Evergreen Museum & Library. (Photo courtesy of Evergreen Museum & Library)

How did this expansion of your presentations change you as an artist? What new artistic concerns/topics are you able to tackle (or old topics better to present) now that you’re no longer solely a formal printmaker?

Mainly I can work much larger, and this frees me to do work that feels much more right to me now.

I saw giclee reproductions of your collages in your Alexandria studio. Why are you OK with offering them?

A few years ago I had a show at Morton Fine Arts (Washington, DC) called Death of the Fine Art Print.

It was meant to raise the question: What is fine art printmaking now? I had degraded images on the floor to walk on and hand-pulled prints of the same thing. I made cardboard rats out of xeroxed prints and painted each one so they were all different. So it was all a question of what was original, what was hand made. Was it the rats or the editioned prints, and why were we walking on images of those prints? I love gray areas in everything.

When I studied printmaking, we had to make an edition that was consistent: No. 1 had to look the same as No. X. Over the years this has broken down. Now everything in the print world is multimedia. Things change. Pigment prints have become archival and much higher quality. Most museums display them. I love the way they look, and I cut them up and use them in new work. So the original is a combination of old images, hand printed, some parts painted. But to me this is much more interesting than a plain wood engraving.

Also I will not deny there is a commercial component. I am a working artist, and this is a way I can sell prints to people who cannot afford my print/painting one-of-a-kinds and make a living myself. Is this not what prints were created for in the Middle Ages? It is only recently that print collecting has become an elitist pursuit. I still have handpulled wood engravings in my studio, and the Georgetown University library has my complete works of 512 or so prints in their permanent collection. But I am always interested in the thing I am doing right now. So I am still experimenting.

Do you see formal printmaking in your future?

I do not think there is such a thing anymore.

In 1996, 1997 and 1998 Rosemary created a series of five large wood engravings on the Vanitas theme. This print Nkonde, based on the traditional African image of a terrifying being covered in nails, was the first in the series. A copy of this print was included in Rosemary’s Evergreen exhibition. (Photo by Scott Ponemone)

Nkonde

1996

14″ x 10″

#45 in an edition of 60

Links

www.rosemaryfeitcovey.com

www.the0project.com

EMAIL

rosemarycovey@aol.com

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/rosemary-feit-covey-printmakers-journey/trackback/