Red Chairs: How they got that way

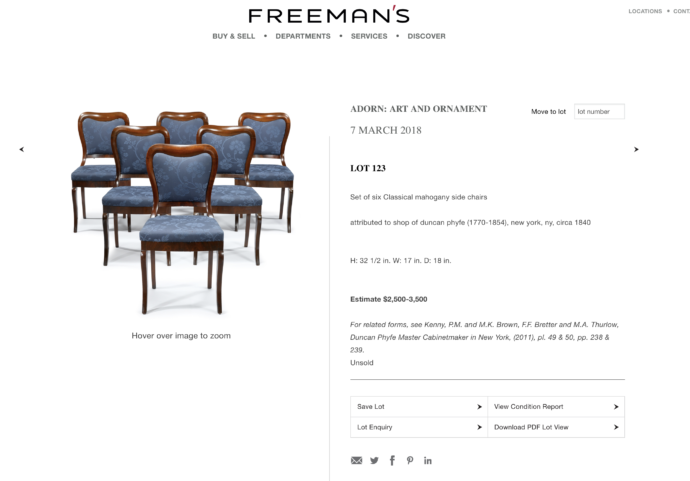

Six upholstered side chairs, probably Duncan Phyfe, New York, 1835-40, height 32 1/2″ The upholstery on the seats and backs are attached to wood frames that are removable. (Photo by Scott Ponemone)

Introduction

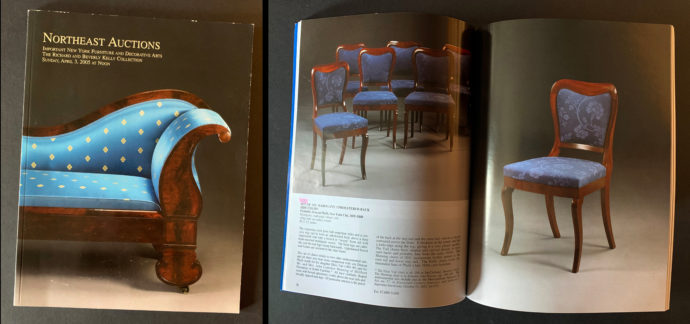

What seduced me into purchasing a set of six New York late classical side chairs were their elegant form, the French polish given the wood surfaces, the quality period-appropriate upholstery, and their stellar provenance. In 2005 Northeast Auctions (Manchester, NH) produced a glossy catalog to promote the sale of the Richard and Beverly Kelly Collection of high-style, 1830s-40s New York furniture, many pieces with association to the heralded Scottish-born cabinetmaker Duncan Phyfe (1768-1854). These chairs were lot #1217 in the sale.

But that provenance doesn’t mean the chairs were well received by antique dealers and collectors. They sold under the $7,000-9,000 estimate in the 2005 Northeast sale. Yet I’m pleased to have bought them from Charles Clark at the 2019 Delaware Antiques Show in Wilmington. (His website is: https://clarkclassical.com) I’ll try to explain why and provide an account of their recent history.

The Kelly sale

Besides color photos and lengthy text with each of the 57 items from the Richard and Beverly Kelly Collection, the catalog featured a short appreciation by the Kellys, followed by two essays: one on the collection by Thomas Gordon Smith, an architecture professor at Notre Dame and principal of Thomas Gordon Smith Architects, and one on Phyfe’s output in 1830-45 by Philip D. Zimmerman, who has written extensively on early American decorative arts.

The acknowledgments by the Kellys began: “We would like to express our sincere thanks to Ron Bourgeault of Northeast auctions for his enthusiasm and willingness to host this first-ever auction devoted solely to New York Late Classical Style furniture of the 1830’s and 40’s.” But being “first-ever” involved a certain amount of risk, which must have seemed reasonable because many of the furniture items had associations with Phyfe with words “attributed to,” “probably” and “Phyfe school.” And one piece, a chervil glass, had a “made by Duncan Phyfe and Son” label. In 2005, however, appreciation of Duncan Phyfe, who enjoyed a 50-year career as a cabinetmaker, had progressed little beyond what was hailed by Nancy McClelland in her 1939 book Duncan Phyfe & the English Regency, 1795-1830 (William R. Scott, New York). While she did show photos of a few 1830+ pieces that Phyfe made for himself or his family, she essentially ignored what his shop produced from 1830 until his retirement in 1847. In her words:

From 1830 to 1847 was his Victorian period, when heavy rosewood and mahogany furniture took place of the former light and graceful styles, for when Empire and Victorian fashions in furniture came into vogue, Phyfe was forced to follow these ideas. His craftsmanship was still fine as ever, his woods were still as beautiful, but the bad taste of the designs which he used, in common with all other cabinetmakers of the time, lowered his standing as an artist.

So the word “Phyfe” came to mean–both for the furniture he made as well as the reproductions made to this day–only the styles from the first two-thirds of his career. That changed in 2011 when the Metropolitan Museum of Art presented the exhibition “Duncan Phyfe: Master Cabinetmaker in New York,” accompanied a catalog by Peter M. Kenny and Michael K. Brown. Phyfe late production, even 1840s pieces showing Gothic influences, was included. (The Kellys lent their 1841 “made by Duncan Phyfe and Son” cheval glass to the exhibition. This was lot #1226 in the 2005 auction and didn’t sell then.)

In 2005, therefore, the essays in the Northeast Auctions’ catalog needed to sell the idea that Phyfe’s later production was eminently worthy of owning. Thomas Gordon Smith wrote: “The Kellys focused on the tumultuous historical period of boom, bust, and recovery between 1830 and 1850. They developed an early appreciation for the boldly scaled scrolls, geometrical pedestal, and architectural moldings characteristic of the times. The furniture is covered with spectacular mahogany veneer that enhances the ‘plain style’ shapes that marked a new sensibility of Grecian furniture.”

In his reference to the chairs I eventually bought, Smith wrote: “These have curvaceous upholstered backs, square seats perched on saber-shaped back legs, and demure front legs cut into a cabriole form. A number of New York shops might have produced chairs of this type, but they are similar to a set owned by Phyfe’s daughter, Eliza Vail.”

In his essay, Philip D. Zimmerman described a distinction between Phyfe’s pre-1830 work and his post-1830 work:

Phyfe’s earlier furniture used architecture to provide a framework for classical compositions that featured animal and plant motifs. In his architectural furniture of the 1830s and 40s, architecture and architectural elements dictated the form and decoration of furniture, almost to the exclusion of classically derived surface ornament…. Brass drawer pulls, escutcheons, and visible hinges disappeared. Even surface carving essentially disappeared. In their place, Phyfe relied on a ‘palette’ of brilliantly figured mahogany veneers and marble that reinforced architectural design themes.

The striking qualities of Phyfe’s architectural furniture emphasize the essence of form. His design is taut, streamlined, spare, even minimal and modernist.

So how did the 2005 auction go?

I called Ron Bourgeault, who ran Northeast Auctions. (The firm in 2019 morphed into Bourgeault-Horan Antiquarians & Associates.) I sought hammer prices from the 2005 sale, but he said that the switch over to his new business made it difficult to access older computer records. But he did recall that the sale didn’t do very well, that it was before interest in Late Classical American furniture, even Phyfe-attributed pieces. He specifically didn’t recall how well my chairs did. One item–#1235, a “probably” Duncan Phyfe pianoforte with a $4,000-7,000 estimate–not only had no takers, but he said that the Kellys had to give it away.

Maine Antique Digest covered the Kelly auction in its June, 2005, issue in an article written by David Hewett. In a conversation with Richard Kelly during a preview of the auction, Hewett said Kelly “admitted that he didn’t have high-dollar expectations for his collection. The Northeast crew members assigned to overseeing the area where they were displayed noted that they had not seen heavy traffic there–not a good sign at a preview.”

In a caption, Hewett wrote: “It was a brave effort because, for many veteran dealers, the style is still ‘Empire,’ and like another word that evokes emotions, ‘liberal,’ some hate it with a passion…. The results of this single-consignor, single-catalog sale were mixed. When bidders loved something, they competed. When they didn’t, they stubbornly sat on their hands.” Elsewhere he reported that 8 of the 57 lots were passed. The top lot of the sale was #1253, a Phyfe-attributed mahogany desk and cylinder desk and bookcase (estimated at $55,000-75,000), that went for $116,000.

Charles Clark

When it comes to furniture, Charles Clark accurately describes his business as “American Antiques of the Classical Period.” (His inventory, however, is heavily weighted toward period lighting, largely English made.) We certainly share an eye for furniture made from 1815-40. Below are two pieces that I enjoy living with that match up quite closely to pieces from his sold inventory:

Philadelphia center tables, c. 1825: (left) from Clark’s sold inventory and (right) from my house. (Photo left from Clark’s website; right by Scott Ponemone)

Both of these center tables share attributions to the well-respected Philadelphia cabinetmaker Anthony G. Quervelle. His work was documented in a series of articles by Robert C. Smith in Magazine Antiques in the 1970s. Those articles stressed that Quervelle hardly ever repeated himself. But these two–except for the tops–are remarkably similar in form and in carved motifs.

Library chairs: (left) from Clark’s sold inventory; (right) from my house. (Photo left from Clark’s website; right by Scott Ponemone)

This form of upholstered American classical seating is quite rare. This pair shares a square back of moderate height and a distinct shape of the arms. Clark attributes his chair to Baltimore, c. 1820. I think he assumed that based on the spiky reeding on the front legs. The biggest difference is that my chair has mahogany veneer on the front of the arms; while his chair’s arm fronts were made to be upholstered.

So no wonder I was attracted to his booth at the 2019 Delaware Antiques Show. And as I wrote to begin this blog post, the set of New York, c. 1840, side chairs immediately caught my eye. They would be a perfect fit in my dining room, and surprisingly I could afford them. Moreover, Clark agreed to deliver them. He also agreed to participate in this blog post by answering questions by email, especially what steps he took to make them ready for the Delaware show.

On 17 November he wrote to me that “I will share my thoughts on restoring the chairs with you.”

When we were given the opportunity to purchase the set of chairs, we moved rather quickly knowing that the form was rare. Having seen the chairs in the 2005 catalog, I knew that I would want to change the upholstery to something I thought would be more appropriate. The seat and back upholstery frames were removed from the chairs. At this point, I removed all upholstery materials that were not period. On these chairs, there were no original upholstery materials to salvage. I removed all the tacks and staples so the the upholsterer had completely clean frames. I provide him with upholstery materials that he uses exclusively on my work. Once any repairs are made to the frames he secures the webbing on the seats and backs. I use a linen webbing procured from an English saddle maker that closely replicates period webbing. It is much stronger than the jute webbing commonly used. Then an unbleached linen is applied. Most upholsterers use burlap at this step. The padding is then laid in the seats. We use curled hog hair in all our upholstery work. I harvest it from upholstery that I take down and take it to the upholsterer where he cleans it and uses it in all of my upholstery projects. After the hair is in place, a muslin cover is secured over the hair.

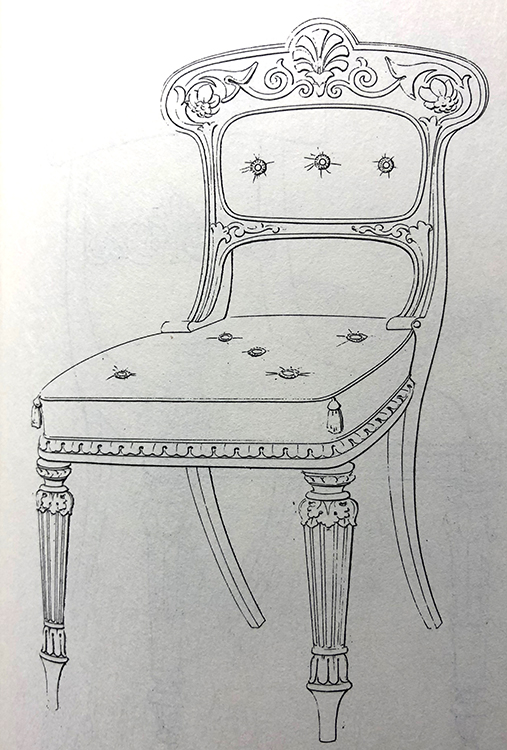

Charles Clark provided this image that he took from a Dover Publications 1995 reprint of Thomas King’s “Modern Style of Cabinet Work Exemplified” (London, 1829). This image of a chair with upholstered seat and back was one of four examples that King labeled “dining room chairs” on Plate 17.

The fabric on the set of chairs is from Scalamandre. It is a linen and wool harateen. Harateens were widely used for upholstery in the late 18th and early 19th century. I refer to early 19th century English upholstery pattern books for ideas for upholstery. The use of “tufts” was seen in the best pattern books. These are the silk “buttons” applied as shallow tufts to the chairs. In order to give a sharp edge to the side of the seat, the upholsterer boxed the seat. To replicate period piping, he came up with the idea of putting string inside of the piping so it would be smaller than modern piping.

Clark also sent me a photo of himself standing beside his upholster who is in his 80s, but he decided not to provide the upholsterer’s name to protect his privacy. He explained:

The upholsterer for all practical purposes retired from the trade at least a decade ago. He does my work and an occasional job for people he knows. For the last 30 years, I have been his primary customer and we have a relationship based on mutual respect. Prior to that he worked with a designer for perhaps two decades who was his primary customer. From time to time other designers have attempted to work with him but inevitably stopped when he was unable to meet their deadlines. He began his career working in a furniture factory doing production upholstery and did not find it very satisfying. Consequently he met an upholsterer who was still working on Belter furniture, which involved hand-stitched edges and extensive tufting and he credits this gentleman for teaching him the skills that he now possesses. After working with this man for a few years, he went off on his own. I consider him to be one of the finest upholsterers in the country. He is one of the humblest humans I have ever met. He is quiet, dignified, and of few words. He does not own a camera, computer, or cell phone and I am going to respect and guard his privacy.

All of which is understandable, but I feel this was a missed opportunity to discuss the upholstery craft with an outstanding practitioner.

Before they were worked on, Clark photographed the set of side chairs without their upholstered seats and backs. Ho noted that the frames for the slip seats and upholstered backs were “all in good condition and all are original.”

After removing the upholstered frames for the seats and backs, Clark brought them to a wood/finish restorer. Here are his thoughts on improving the finish:

Finishes on furniture this old always present challenges. My philosophy for restoration is to offer the furniture as the maker originally intended it to look. Most of the time a nice piece of furniture is going to be “freshened up” every generation or so. This accumulation of shellac and lacquer finishes begins to darken and obscure the ability to see the woods through the finish. Using denatured alcohol on a cloth, the restorer begins a process of removing the old finishes. This takes time but is safer than stripping the old finishes. The idea is to remove the incorrect finish but not too much color so that the chairs have a nice old original look. At this point, the restorer makes any repairs to the chairs using hide glues and begins applying an appropriate shellac finish. It is composed of shellac flakes dissolved in denatured alcohol. This process can take days to accomplish because the finish must dry between applications. The finish is built up with successive layers until the pores of the wood are almost but not completely filled. The end result will be just the right amount of reflection and refraction of light on the finish. A competent polisher learns how far to go and when to stop.

In another email, Clark wrote, “I work very closely with the restorers, making multiple trips (four for your chairs), to discuss, consult and confirm accuracy.”

The work on restoring and reupholstering the set of chairs was completed just in time. Clark wrote: “We literally received the seats and backs days before we left to come to the Delaware show.”

Before Clark

I also wanted to mention how Charles Clark got the chairs that I eventually bought. It turned out that I knew something about their history that he didn’t know. But here’s what Clark had to say:

The couple I purchased the chairs from bought them at Northeast Auctions from the sale in the catalog that I gave you. Shortly after the auction, I recall seeing a picture in one of the trade papers of the chairs in the lady’s booth listed for $7500. In the caption under the picture, it was noted this was their last antiques show as she was retiring. At the Philadelphia Antiques Show this past April, an older couple approached Teri [Hay, Clark’s partner] and talked about having been an antiques dealer many years ago. She told Teri that she had a set of six chairs that she knew only we would appreciate. She said she bought them at Ronald Bourgeault’s auction, that after that she took them to her last antiques show, retired, and then put them in storage for many years. Some time ago they decided to live with them. Her husband drew a little sketch of a chair and Teri knew the style and gave them a card to please email a photo of the chairs to Charles. I corresponded with her, and we purchased the chairs in early June. Teri picked them up on a trip to Lancaster as I committed to the chairs from a photograph.

At my request in November Teri wrote to the sellers of the chairs. She sent me the text of her letter in which she said, the purchaser of the chairs “researches pieces and was aware of the history of the chairs. He writes about his pieces in a blog including the history of how pieces have been cared for over the years. He would like your permission to allow him to include your name in the provenance of the chairs to his ownership as he prepares this for his blog.”

In early December Clark wrote: “Teri has already sent two emails to the seller and one follow-up phone call. [One of the sellers] indicated that she was a generalist dealer and entering retirement mode at the time of the purchase of the chairs. They are elderly and are dealing with health issues. After three attempts, we are not comfortable pursuing them beyond what we have. Teri gave them your email and links to your website/furniture blog.”

The one part of the chairs’ history that Clark didn’t know about was that the couple who sold them the chairs had placed them in Freeman’s March 7, 2018 auction in Philadelphia. Even with an estimate of $2,500-3,500 they didn’t sell. Obviously they were the same chairs from the Kelly sale in 2005. The upholstery hadn’t changed.

But now the set graces my house. Yet I wonder if I’m such an astute collector of American classical furniture. They sold for $4,060 (Clark, in a January email, said his copy of the Northeast’s Kelly catalog had the hammer price of my chairs noted in pencil) well below the $7,000-9,000 estimate and had no takers in 2018 despite a much reduced estimate. I just might not be a great judge of the market. But I do love the chairs and wouldn’t have bought them had Charles Clark not employed such talented artisans to restore them.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/red-chairs-how-they-got-that-way/trackback/