New School Wood Engravers: forgotten 19th-century celebrities

AN INTRO

I don’t know whether the gist of this post is a cautionary tale about fleeting artistic fame or simply an appreciation of an author who recently set the record straight regarding the brief heyday of a very specialized school of American printmakers. Maybe it’s both.

Before William H. Brandt published his book Interpretive Wood-Engraving: The Story of the Society of American Wood-Engravers (2009, Oak Knoll Press, New Castle, DE), I certainly–perhaps most people familiar with these printmakers–would have called them reproductive wood engravers, not interpretive ones. For the most part these printmakers worked for magazines like Harper’s and Scribner’s to create images on endgrain wood blocks to reproduce paintings in subtle shades of grey. When they created the Society of American Wood-Engravers (SAWE) in 1882 and then published a magnificent elephant-folio book in 1887 Engravings on Wood, they forbid personal expression in their work. In his essay in Engravings on Wood, William M. Laffan wrote, “The principle characteristic of American wood-engraving it its simplicity, its sincerity of purpose, and the cheerful self-effacement of the engraver. His endeavor is to reproduce the work of art he has to do, be it his own or another’s, as faithfully as possible; to adapt as far as possible to that end the means he controls, and to make his reproduction give a maximum of the qualities and characteristics of the original.” The operative word is reproduction. In other words, skillfully reproduce a work of art as a wood engraving but don’t let yourself show through. But Brandt focused on the next sentence in Laffam’s essay: “He is not concerned about his line, does not know he has a line, and addresses himself sole to the thing at hand–the faithful interpretation into black and white eqivalents of the subject before him.” For Brandt the operative word in interpretation.

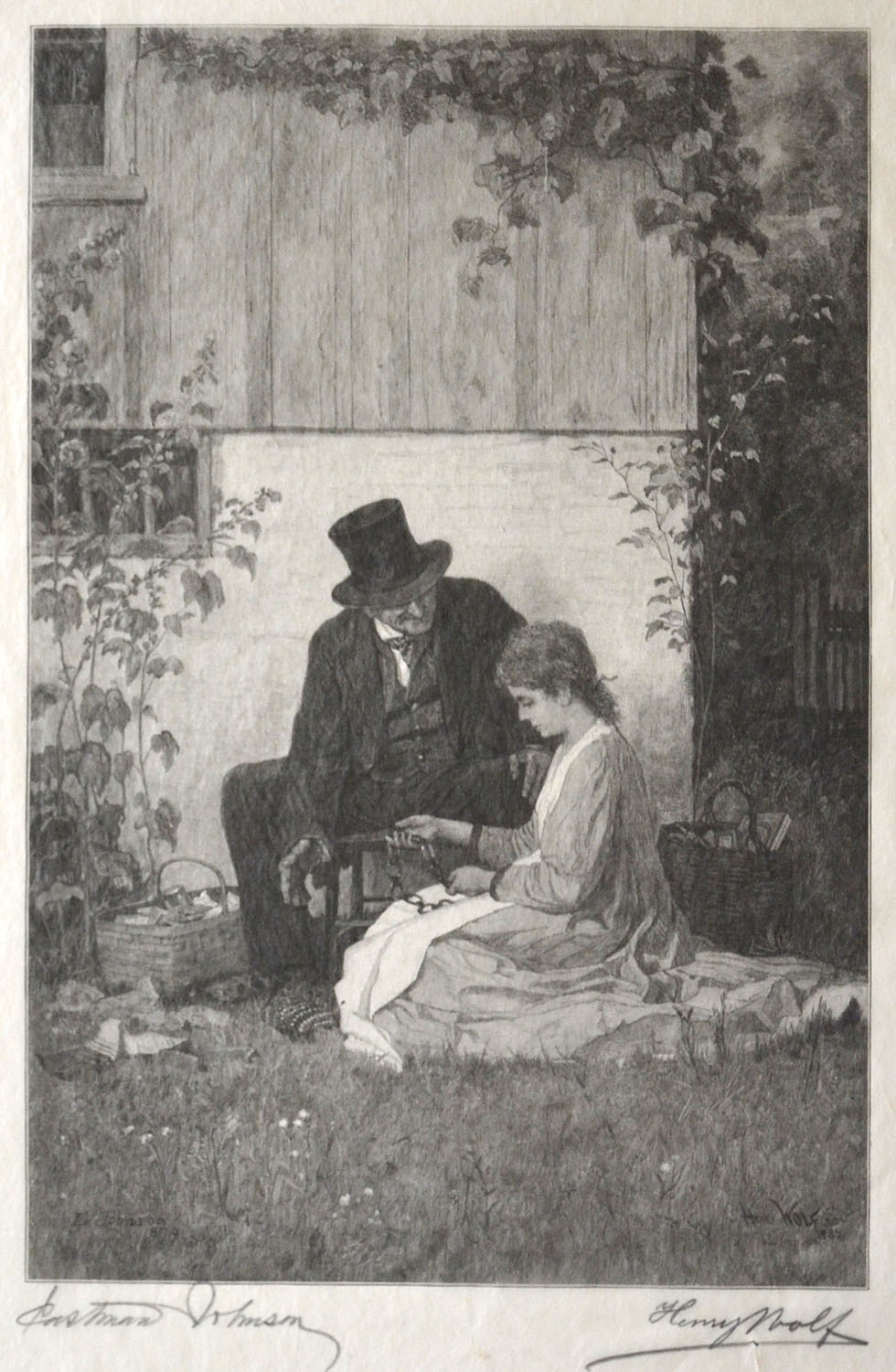

The New England Peddler, 9 5/8″ x 6 1/2″, engraved by Henry Wolf from a painting by Eastman Johnson–from the deluxe edition of Engraving on Wood, printed proof on Japan tissue signed by both the engraver and artist.

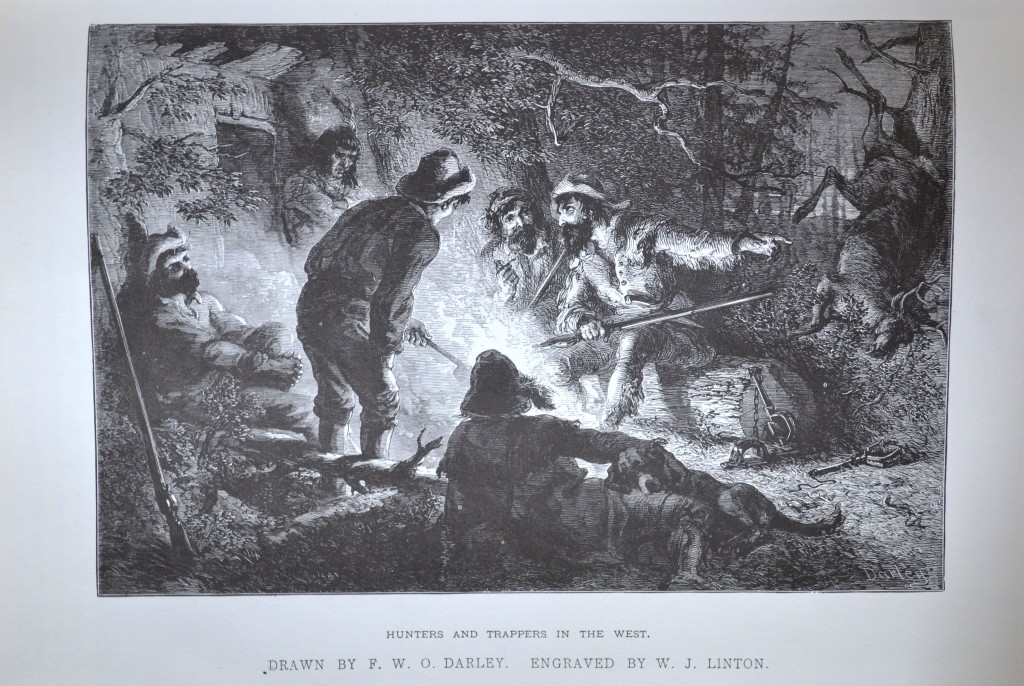

The word intrepretation is important to Brandt because it goes into the heart of the brouhaha that seized the printmaking art world c. 1880. One one side was the Englishman William J. Linton, who emigrated to American in 1867 and became a very influential wood engraver. In his book, Brandt said: “The American engraver John Park Davis [one of the founders of SAWE] summarized one of the traditional views that Linton espoused, noting that a certain kind of line ‘should be used to represent ground; another kind to represent foliage; another to represent sky; another flesh; another draper, and so on.’ ” Linton came to be the rather outspoken leader for the Old School of engravers, who–to quote Brandt–believed “that only certain lines could be used for certain effects, and that it was possible to superimpose their designs over those of the artists.”

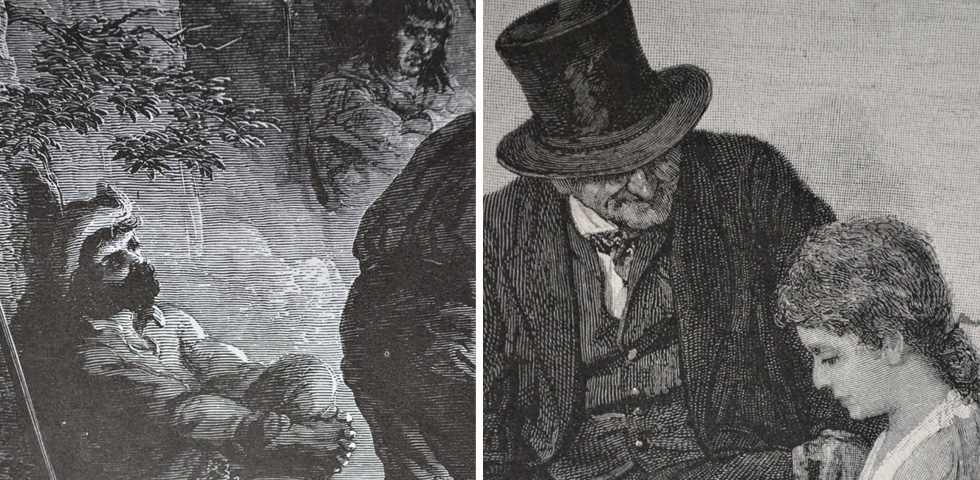

An engraving (above) by William Linton from his book The History of Wood-Engraving in America, 1882. Below is a comparison of closeups of the Linton (left) and the Wolf (right). Note that Linton used mostly parallel lines of various lengths and widths to create his image, while Wolf used a variety of techniques, including cross-hatching, dotting and parallel lines that follow contours.

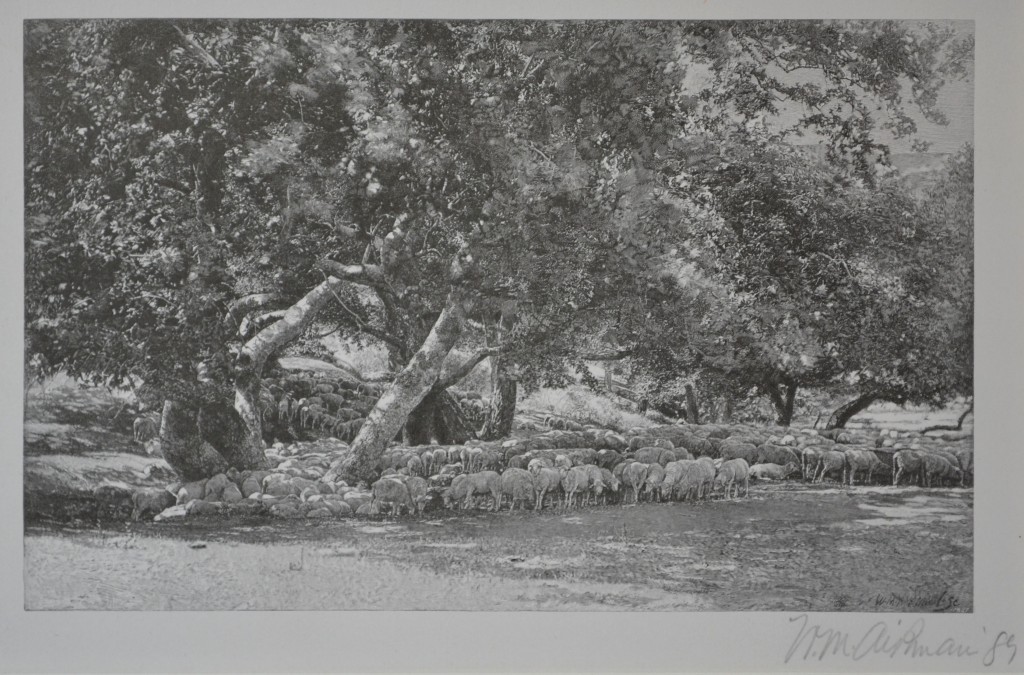

Among the things I hadn’t appreciated until I read Brandt was that the American New School of engravers were so dependent on photography. I knew of at least one signed engraving in my collection that had to have originated from a photograph, if only because it looked so photographic. And that is the image below by Walter Aikman, Scene in Hope Ranch, 5″ x 7 7/8″, 1889.

Brandt wrote: “… members of the New School considered transferring images onto wood blocks through photographic techniques to be an important advance. Photography not only made it possible to reduce an image of any size to the size of the block, it could also reverse it so that when printed, the image could face the same way it did in the original.” So the controversy raged with Linton’s Old School espousing a correct, traditional way to do engraving, while the American–this was an American development–New School felt free to use whatever types of cuts into the wood block needed to faithful interpret the original work of art into lights and darks.

Well, this New School caught the public’s eye, ditto for at least some cognoscenti, because these adherents won all kind of awards at national and international expositions. But the celebrity of New School engravers was meteoric–a big flash and then nothing. By the 1890s, the halftone process of making metal plates for reproducing photographs on the same sheet of paper with metal type was developed. Brandt wrote: “Ironically, the camera … that had played such an instrumental and helpful role for the New School of American Wood-Engraving, now virtually destroyed the profession.” Born in 1882, SAWE essentially died by 1895. In short, the New School lived by the photograph and died by the photograph. And so went their technique, or as William Brandt named his preface: “The lost Art of Interpretive Wood-Engraving.”

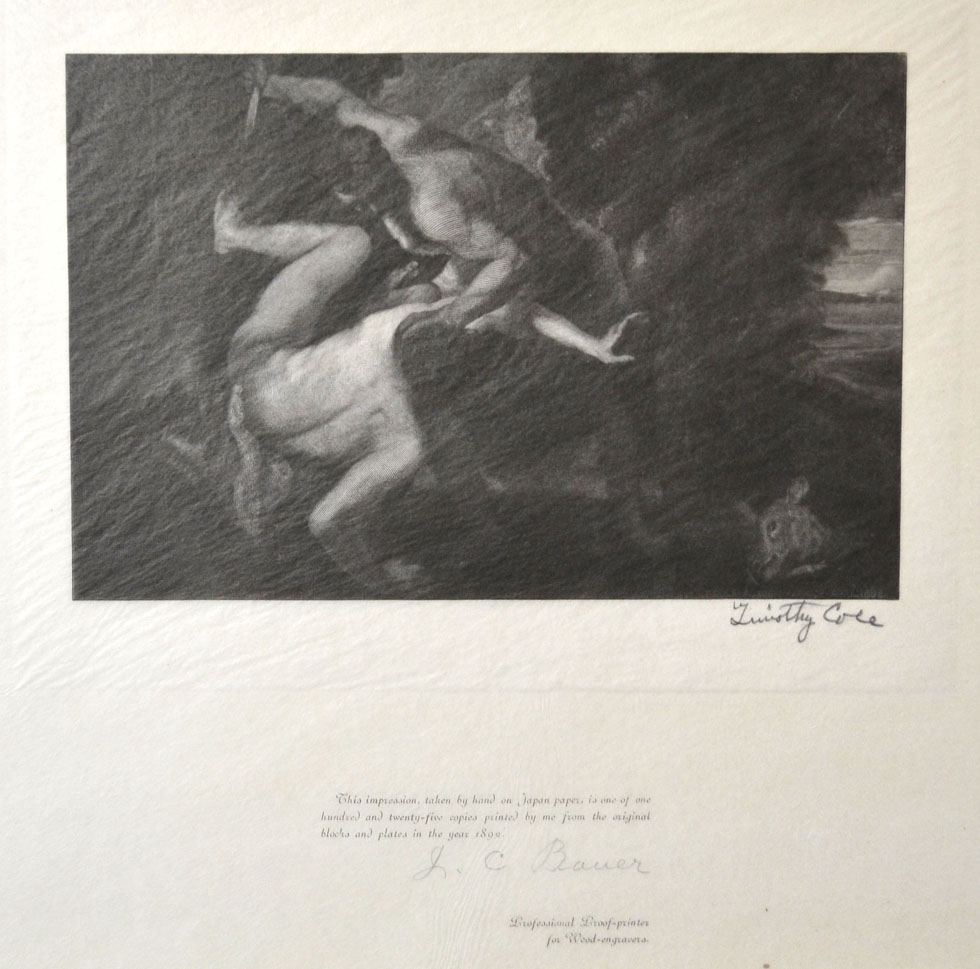

Brandt’s book also shot down an assumption of mine. when I had looked through the pages of the huge SAWE volume, I had thought I was looking at images printed from the wood blocks. Wrong! I was looking as electrotypes, images taken off metal plates that were electrically-made facsimiles of the original wood black. Brandt gives two reasons: 1) the metal plate withstood the pressures of the printing press and could last for as many at 100,000 impressions and 2) the original, so delicately carved wood blocks were immensely difficult to print. So difficult were they to print that in New York, the heart of the publishing business, the New School engravers relied mostly on one man, John (J.C.) Bauer, to do the proofing. It took him hours to adjust the proof press with various shims and make-readies. He also needed to use the finest of tissue paper, usually called Japan paper, to print on. So, thanks to Brandt, I learned that only the images on Japan paper could usually be called wood engravings. However, Bauer and others did print proofs directly from wood blocks onto wove paper that were signed by the interpreters. Below is a proof by engraver Timothy Cole of Tintoretto’s painting The Death of Abel. Note that J.C. Bauer also signed the impression. This came from a set of 67 proof impressions from 1892 of images Cole cut for the book Old Italian Masters.

As a collector since 1980 of mostly American prints from the 1920s, ’30s and 40s, I found myself gravitating to relief prints. I loved the energy between the black of the inked ares and the white of the paper. And wood engravings–relief images created by cutting into the endgrain wood blocks–I found particularly fascinating. I was in awe of the detail. So when I first saw a New School engraving (of course I didn’t know it by that name), I was floored. A curiosity, I thought. A minutely cut reproduction of a painting. So I bought it to help tell the story of wood engraving. For the same reason, I jumped at the opportunity to buy four volumes of lifetime impressions (c. 1825-7) of blocks by Thomas Bewick, the British godfather of wood engraving. Now, thanks to Bill Brandt’s Interpretive Wood-Engraving, I can better tell the whole story of wood engraving.

Please turn to the next post in Art I See for an interview with Bill Brandt.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/new-school-wood-engravers-forgotten-19th-century-celebrities/trackback/

Pingback: Scott Ponemone – Interpretive Wood-Engraving: interview with its author