Making a COVID BOWL with Eric Avery: Part I

All images of artwork by Eric Avery are used with the permission of the artist.

An invitation

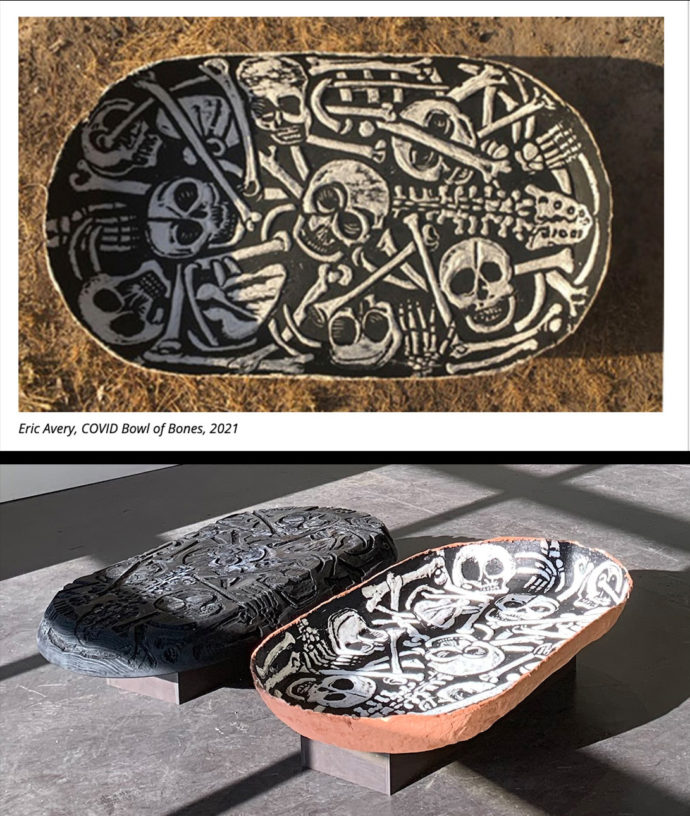

“COVID Bowl of Bones” was shown with the Mexican serving bowl that Avery carved to make the print. (Courtesy of Kirk Hopper Fine Arts.)

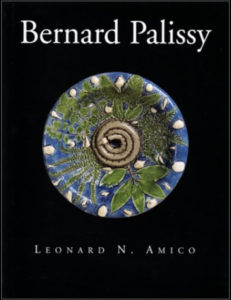

As soon as Eric Avery sent me a link last fall to his new exhibition at Kirk Hopper Fine Art gallery in Dallas, I read the exhibition essay and stopped short at an image of Avery’s COVID Bowl of Bones, 2021. (Right top) Photographed in raking sunlight, the shadows revealed its deep dimensional character. Then I check out Avery’s website: docart.com. There was the same artwork on the home page and a click on its Print Catalog link confirmed that it was one of Avery’s molded paper woodcuts–and this one an impressive 44 inches across. Avery carved the underside of a wooden Mexican serving bowl to serve as the matrix for his print.

In a series of emails in December 2021, Avery sent me a photo from the installation in Dallas showing COVID Bowl of Bones placed on a very short pedestal (nearly on the floor) in the middle of the room. Avery wrote: “The COVID bowl is a showoff print made for this exhibit. I exhibited it low so [it was] like looking in a grave.” (Right bottom)

After I further expressed my enthusiasm regarding COVID Bowl of Bones, Avery wrote: “I’m happy you like the bowl and showed it to Michael (my husband). I made several preparing for the exhibit. The last two made have reddish brown earth pigment in paper pulp so the underside is colored–almost like dirt of a grave.”

He added: “The wooden bowl stays wet from paper pulp for 24-36 hours and then dries. Already after two printings, the wooden bowl begins to crack from the swelling and shrinking of the wood. Thompson’s WaterSeal helps. I put edition size at 10, but with two brown ones, I probably will not make another. Each can take several days to make, and I don’t want to destroy the beautiful woodcut bowl.”

He then offered to sell me one, noting that “It would cost several hundred to box and ship it. Or you drive down when the weather is beautiful, visit and we make one together and you take it home in your car. It’s a two-day drive.”

Well, I wasn’t about to drive to his studio in San Ygnacio, a village along the Rio Grande, south of Laredo. But the notion of working with Avery to make my own copy of his COVID Bowl of Bones was too exciting an opportunity to overlook. So I set about arranging a nine-day visit in March to Texas including flights to San Antonio, where I have a host of relatives, and car rental so I could drive 3.5 hours (a Texas short haul) for four days in San Ygnacio.

Collecting Avery

Judy and Tom Brody ran Brody’s Gallery a block or so north of the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, from 1983-94. The gallery was just around the corner from Gallery K on R St. where I was part of the stable. My first purchase from Brody’s was James Lesesne Well’s 1928 woodcut Looking Upward. In 1992 I bought Avery’s Haitian Boat People, a photo-engraving that was a small version of his 1991 linocut over lithograph USA Dishonor and Disrespect (Haitian Interdiction 1981-1994). My small Haitian Boat People was sold as a fundraiser for Amnesty International. About that time the Brodys exhibited Avery’s huge 1984 linocut Massacre of the Innocents at the Baltimore Contemporary Print Fair, which was founded and run by Curator Jan Howard at the Baltimore Museum of Art. But I didn’t purchase it until the Brodys announced the closing of their gallery in 1994. Not only did I buy Avery’s Massacre then but also his 1984 molded paper linocut Les Demoiselles de Avignon de San Ygnacio. (Judy Brody died on 18 March 2022.)

My conversations with Eric Avery–I should say Dr. Avery since he was a psychiatrist who had worked with AIDS patients for 20 years at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, TX–didn’t start until I visited “The Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy,” an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art (Oct. 14, 2018–Jan. 20, 2019). To my delight, it included Marcantonio Raimondi (Italian, c. 1480–c. 1534), “Massacre of the Innocents,” c. 1513-15, an engraving based on a drawing by Raphael. That is the image that Avery adapted for his Massacre. The exhibition also in included the chiaroscuro woodcut version that Udo da Carpi made c. 1520-27.

Three 6′ x 6′ pairs of Avery’s “Paradise Lost” were hung at East Tennessee State University’s Reece Museum. (Courtesy of Eric Avery)

But when I contacted Avery to talk about his Massacre, he said he was about to leave Texas for East Tennessee State University in Johnson City, TN. He said, “I’m working on an exhibit–Epidemic–and will teach two classes. The heart of the opiate epidemic is in Appalachia, and I’m working on what I call ‘Narrative Naloxone, Art for the Spirit,’ whatever that means.” As a result not only did I write an ART I SEE blog post on Massacre but also on his semester in Tennessee. See “Eric Avery: Doctor of Printmaking” LINK

The three pairs of Avery’s linocut banners Paradise Lost (above) were hung during the Epidemic exhibition in Tennessee. They were printed on atop banners printed with an enlarged, reversed digital image of Albrecht Dürer’s famous 1504 engraving of Adam and Eve. So taken with these banners that I offered to buy a set. Fortunately I had just enough room above the mantel in my dining room for the pair. The best part of the purchase was meeting Avery, who arrived August 1, 2019, and helped hang them. This led to my ART I SEE blog post “Eric Avery: Paradise Arrives” (LINK). In it I wrote: “Not only did I purchase a pair of Paradise Lost banners but agreed to buy a copy of 14 Major Infections of Adam and Eve. In turn, Avery gave me a copy of Emerging Infectious Diseases, a linocut over litho from 2000.” (14 Major Infections of Adam and Eve was a three-color chiaroscuro linocut version of Paradise Lost.)

Interview Introduction

In short, I went to San Ygnacio and made a copy of COVID Bowl of Bones and recorded the process. (Part II of Making a COVID BOWL will illustrate that effort.) Then back home, awaiting the shipment of my copy, I edited the photos and short videos and was ready to start a blog post. But then I stopped. Could I really tell the story about COVID Bowl of Bones without putting its inception into the context of Eric Avery’s 40-year history of making dimensional relief prints? COVID Bowl of Bones from 2021 is in some ways the culmination of his efforts. So I asked Avery if he would agree to a Zoom interview that I would have recorded. He agreed and in March 2022 we did so.

The following is based on the transcription of that interview.

Interview with Eric avery

Ponemone: Welcome Eric Avery. I’ve had the pleasure of visiting you for four days in San Ygnacio and making a COVID Bowl. Throughout your life, you’ve shown yourself to be an incredibly compassionate person. Can you express how your life as a physician and psychiatrist and your life as an artist are all one in the same?

Avery: Well, you know that you’re talking to a psychiatrist. So nothing is simple, Scott. How does anybody become who they are, you know, it has to do with genetics, family, and in my case, privilege. I’m the son of a physician; my mother was an artist. And I’m just the person that I was, and I was nurtured and cared for. But in any case, so I be. I just grew up being a person who felt things about other people.

P: You just showed me some prints that you did as a child. So there’s one of your earliest expressions. You actually were selling these note cards. So you were a professional back at what age?

A: Yeah, I was 12 years old. So this is a woodcut with a little linoleum cut printed on top. I could get attention from my mother by making things. She was very interested in my Ladybug prints. I had four brothers. So there was a lot of demand on my mother.

This is another one where the bug is just flying across and getting zapped in front of the sun. So these themes were pressing on me when I was a child. I grew up in West Texas, and I was trying to sell these cards in a yarn shop in Pecos. And so I’ve been making prints for a long time.

My making things, Scott, is a way of processing and dealing with emotional feelings. That’s how I have connected up my art making and my life. I think I was kind of born an artist. And I was encouraged. And I began to make things. And my own therapist helped me understand that, when you make a block or make paper, there’s a lot of cutting, chopping, that’s kinesthetic, or body working through of emotional feelings. I’ve been doing this for a long time.

P: Well, no doubt, the emotions boiled up and had to be released when you were working in Somalia. Can you explain who you were working for in Somalia and the extent of the trauma that you saw?

A: Well, before I got to the Somalia, I volunteered with World Vision, where they needed a position was on ship SeaSweep that was moving Vietnamese boat people around. I had finished all my medical and psychiatry training in New York City at Columbia Presbyterian New York State Psychiatric Institute. I took a break from medicine. I had told myself that, when I got to the end of however long my medical training was, I would take a break and go back to my art. And I did and ended up living at that time, inexpensively in a little border community–San Ygnacio–Michael Tracy, an artist friend, let me stay in one of the studios.

World Vision called and I went and worked on a ship in Indonesia. And very quickly something happened that was so traumatic I won’t even go into it. But there was a young woman who couldn’t deliver her baby and it had died inside her. We had to do a destructive procedure to take it out. I was not prepared for this. I had a midwife who helped and an Indonesian doctor. Besides moving Vietnamese refugees, we provided health care in Indonesian villages around the camps.

(R) The ironing board that Avery carved beside (L) his plaster “Noa Noa” print, 20″ x 7.5″ x 1″ (Avery photo)

But what I then did in the Vietnamese refugee camp, Scott, was this: The camp was basically empty of people. This is an ironing board used by Vietnamese people. I took that ironing board back to my ship, and I carved out the woodcut. I was traveling with a book about Paul Gauguin. I don’t remember how I got it, but I carved “Noa Noa,” the name of a South Seas travelogue by Gauguin, at the base of the ironing board.

Nor do I remember how I got ink. I didn’t have paper. I had this idea about working with plaster. So I just put plaster onto the inked ironing board. And I made this plaster print. And you can see all the cut marks, which carry my emotions. They stick up in the print. So instead of just printing the surface of the block, I’m actually printing where the gouging is going. And that sort of led me into the dimensional printing. So all the emotion in carving is in the gouging. I was able to print those by getting plaster to go into those marks. William Stanley Hayter had described making plaster prints from his etchings in his book “New Ways in Graveur.”

(To see 1979 photos of Vietnamese refugees aboard the World Vision ship Sea Sweep in Northern Indonesia, go to: LINK)

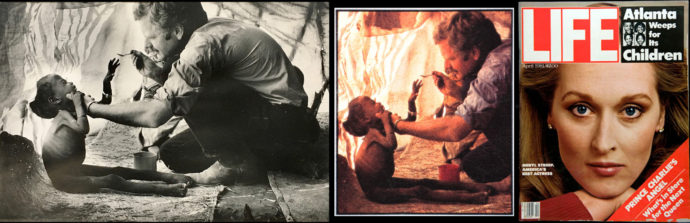

The Harry Benson photo of Dr. Avery feeding a severely malnourished Somali child appeared in Life magazine in April 1981 for the article “Parched Land of the Dying.” LINK

Then World Vision moved me to a refugee camp in Somalia. At that time, it was the worst. It was the worst starvation camp in Somalia. And I went in to head a medical team. The German Red Cross was in that place helping out. We were feeding thousands of starving children. And I’m going to turn my camera around and show you [a photograph from] Life magazine. The photographer was Harry Benson. He came in and did a story on this camp in Somalia, and he sent me this photograph of myself. Somalia was an overwhelming experience.

Eric Avery, “Starving African Child with AIDS,” 1987, molded paper woodcut from Mexican wooden washbowl, 24.5″ x 13″ x 2.5″ LINK in dogcart.com (Avery photo)

When I returned home to Texas from Somalia, it was to San Ygnacio where I had rented my studio. I went into a shop in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, where I saw a wooden wash bowl that was the size of one of those starving children babies in Somalia. I bought that wooden bowl and I carved out the image. I couldn’t get my paper to go down into it. And it was not going to work with plaster, because the plaster was too heavy and would break. So I needed to learn how to make handmade paper. By putting the paper down into the wash bowl, you can see the ribs that were used for washing, but they were like the ribs of the starving child.

P: I feel quite emotional. Just by looking at that I can imagine the emotion you were putting into it and how the cutting was kind of a release for you?

A: It was, it definitely was.

P: Who did you turn to to learn how to do make your own paper for your wash bowl woodcut?

A: Her name is Susan Mackin Dolan. She had set up the Picante Paper Studio and the Southwest Center for Art and Crafts in San Antonio. It’s now part of the UTSA system. Susan came down to San Ygnacio and we work together. We started with water-based inks thinking that the oil wouldn’t cross over onto wet paper. But actually, when the paper dries, it sucks up the oil-based ink. So we figured out the recipe. We used cotton linters, which is a short cellulose fiber. And it’s also mixed with abaca, which is a banana fiber from the Philippines which is longer and stronger. And by mixing more of the cotton linters and some of the stronger abaca fibers, you can get these dimensional objects to really be strong. That was the pulp that we used when you came down to make your print here.

P: So you essentially had that formula down quite early in your molded-paper relief print career.

This is the repaired wooden Mexican bowl (left) that was carved on the bottom (middle) to make the 2006 molded-paper woodcut “Bowl O’Bones,” molded paper woodcut measures 30″ x 30″ x 6″. (Avery photos)

A: Well, I’ve been making these dimensional prints since the 80s. That’s for 40 years. So yeah, I know a bit about making paper. This is another bowl that I made from my AIDS doctor time. This is a Mexican serving bowl. When you use wet paper, the wooden bowl swells and shrinks. This one has been patched to keep it from splitting in half. But this is the wooden bow turned over. And by working on the backside of the bow and putting ink on this and then putting handmade paper on top of that, you end up making a paper bowl.

I’m going to show you one more thing because this is one of my favorite artists in the history of art. And he was French; this is 16th century. (Avery holds up a book.) This is Bernard Palissy. When Michelangelo was painting the Sistine Chapel, this guy’s atelier–or his ceramic studio–was set up where the Louvre is. When they excavated for the I.M. Pei Triangle, they found where his kilns were. Palissy did these incredible dimensional objects with clay. I loved this work anytime I got a chance to see it. Let me find one of his great bowls which has snakes and snails and shells. These objects are incredible. He made molds from real animals. He then pressed the clay down into his plaster form. That’s how these bowls would have been made. So that inspired me, and I just had to figure out how to do it with paper.

P: Did you see yourself also making an overall form and then building up separate molded objects that you then attach? I don’t know if you can do it all in one big mold.

Eric Avery, “HIV Condom Piñata,” 1993, molded paper wooden, 8 1/2″ diameter, shown with wood mold. (Avery photo)

A: Yeah, so this is my 1993 HIV condom-filled piñata in the form of the HIV virus. This was made when I was practicing medicine. Part of my time was protected by the Institute of Medical humanities at UTMB. So I had the time to make art about what I did as a doctor with AIDS patients. Some of my patients were going blind from CMV retinitis. I had this really sick idea that if I made piñatas with condoms in them for like a party. The person who had gone blind wouldn’t need a blindfold to smash around at the piñata. So it’s dark humor. But in order to make those, I needed to get a carpenter who would make like a big salad bowl for me. So this is the form that was used to make one half. And when you make a second one, they’re exactly the same. When you put them together (if they have condoms inside this one, of course doesn’t), you end up with with a piñata. (To see the production of his piñatas, go to LINK) I have a bunch of them up on my ceiling where one of my storage rooms is. Can you see them?

P: Yep, I see them.

A: So those are left over from when Harvard put up a clinic for me in the art museum. (Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum exhibited Avery’s work during “Art as Medicine/Medicine as Art” in 1997. LINK)

P: At a piñata party, were those were busted open.

A: No, they were no parties. I used the piñatas as atmosphere around my HIV Clinics in art museums, like in the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard. They were floating around the clinics above in the air like viruses floating around in blood.

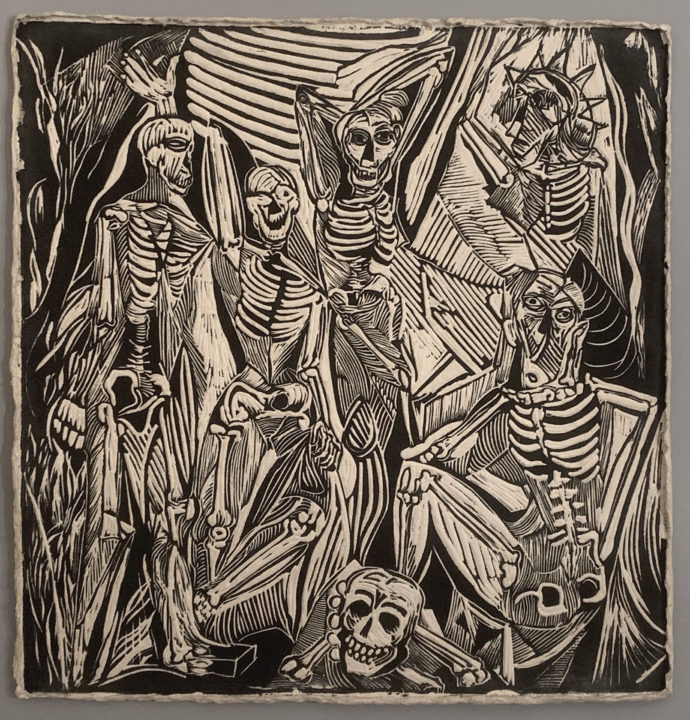

Eric Avery, “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon de San Ygnacio”, 1984, molded paper linocut, 28″ x 26 1/2″, ed. 6 (Ponemone photo)

P: So I have one of your early dimensional prints that I got from Brody’s Gallery in Washington. It’s called Les Demoiselles d’Avignon de San Ygnacio. It’s a skeletal version of the famous Picasso painting. But why did you do that print?

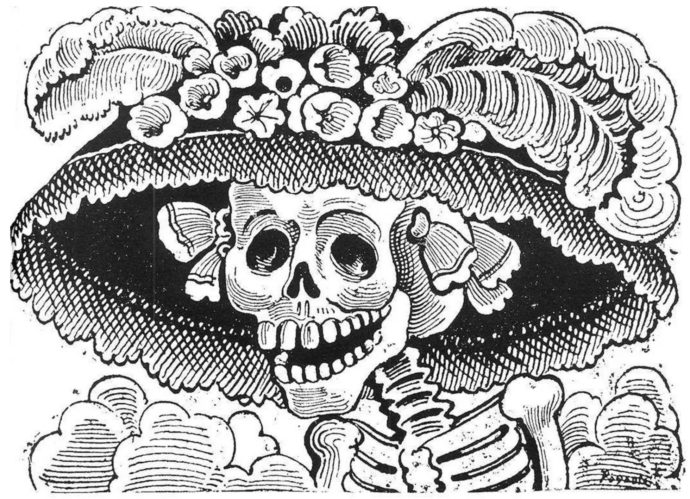

A: Well, when I came back from Indonesia and Africa, I needed a way to talk about death. Of course, I had become completely involved with the work of Mexican artists like Jose Guadalupe Posada, who who did the calaveras, the skeletons. He was an illustrator for Mexican newspapers and periodicals and games. He used skeletons to make political commentary. That La Calavera Catrina is a wealthy woman. She’s a skeleton; she’s just the head. And she’s got a large hat with large feathers in it as wealthy people would wear. That’s La Calavera Catrina.

When I began to appropriate the use of those skeletons, one of the things I’d begun doing was printing my linoleum blocks atop anything. When I printed it on top of the Picasso image, what I did was put death on top of it. LINK And that time El Salvador was falling apart. Well, it wasn’t falling apart, but it was a terrible time and lots of death and killing. So I just started using these skeletons to try to make comments on my own experience with death as a physician in Africa. And you just got a really early overprint of mine. Right?

P: No, I just had the molded version without the overprint.

A: That’s a really good example, Scott, of the cut marks in that really captured the bone quality of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon de San Ygnacio.

P: Another important print was your 1986 Blood Test, a large arm of a molded, dimensional image. You used it again and again, especially when you start talking about the opioid epidemic?

A: This is the Blood Test arm. And that’s my arm. That’s my first blood test. This when I when I got my HIV test, the very first time that the test had come out. I’m gay. I guess everybody figured that out. When the test first came out, I drove to Houston to get the test. And they said, since you’re gay and you’ve been in “those places, come back in 10 days, and we’ll tell you if you have HIV. You should go home, and you should just really prepare yourself to be positive.” Everyone was dying. What I did was: I went home and on my way home I stopped in Austin and I got this piece of wood. It’s a pecan plank. Never had been smoothed out or sanded. And I brought it back to San Ygnacio and I carved out my arm like I was getting a blood test. And then in order to print the woodcut, since it’s not flat, it’s round, a piece of flat paper really won’t work. So I then working with Susan, this is when we really figured it out. I made the handmade paper that would go on top of it. This is not the greatest impression because it’s 40 years old. The one that’s in the British Museum is a beautiful impression.

A: I’ve showed you a lot and talked about the origins of my dimensional prints. The only thing we haven’t seen is my COVID Bowl woodcut. This is the wooden bowl for your COVID print. I’m just going to turn it over so people can see that it’s really a large bowl shape. It’s a large Mexican serving bowl. I’ve had it for 40 years. You can’t cut down these trees in Mexico anymore. So I have had it, and I was saving for a special, terrible situation, which was the COVID time. This is actually the third Bowl of Bones that I’ve made. [The first was in 2006.] But this one is the biggest one, and this is about about the COVID time.

P: Well, you’ve previously described the wooden box that was made for the shipping of my copy of it. (I hadn’t received it at the time.) I was wondering would it be appropriate to show the box with the bowl inside as if the box was a coffin?

A: What a cool idea. When I’ve exhibited in Dallas, I showed it low on the ground like you’re looking into the grave. So Scott, you have a beautiful box now. I haven’t seen it on the inside, but the outside of it the edges are beveled. I mean it’s a beautiful wooden box. You decide whether you leave it in the raw wood (it’s birch I think). You make that decision, Scott, you’re the artist.

P: Well, I’ll find out when I get it. I’m really excited.

(After I texted Avery the above photo, he wrote back: “Looks good in box, but I made it as a free commemorative bowl so it can be picked up. People are amazed when they hold it. It’s so light.” My response was to display it without the box.)

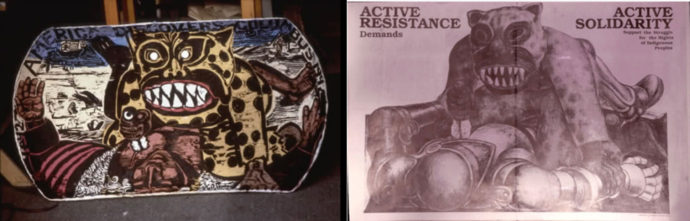

(Left) Eric Avery, “American Discovers Columbus, 1492-1992,” 1992, molded paper block on pigmented handmade paper, 28″ x 38 1/2″, ed. 2 (Right) Detail from Diego Rivera’s “Conquest,” 1930, Palace of Cortez, Cuernavaca, Mexico

You know there’s one other print that I kind of liked because it’s not bones, but it’s America Discovers Columbus 1492-1992. It’s another dimensional woodcut.

A: That commemorated the 500th anniversary of Columbus in quotes “discovery of America.” For that image there is the Diego Rivera detail that I appropriated which is a conquistador in steel armor being stabbed by a jaguar-hooded figure on the beach. What I did was a portrait of Christopher Columbus lying on his back with his legs spread, and in between his legs is this jaguar-hooded figure that is stabbing Columbus and also raping him at the same time. And then his pants are in the background, and the boat is in the background. It’s got the “1492” on one side of the rim and “1992” on the other. The title is running on the rim of the bowl, and it says “America discovers Columbus” It’s beautiful.

P: I think so too, and very colorful. At the same time, it has an organic, visceral quality to it.

A: I wanted to add color. That is the Hockney use of color when he made his swimming pool molded papers. So on that Columbus bowl, I’m working on the outside the bottom of the wooden bowl. After inking it, I put your colored pulp where I wanted the skin color; this color for the head of the figure, etc. Then I placed layers of white pulp, then a layer of brown pulp. So it’s a colored pulp woodcut.

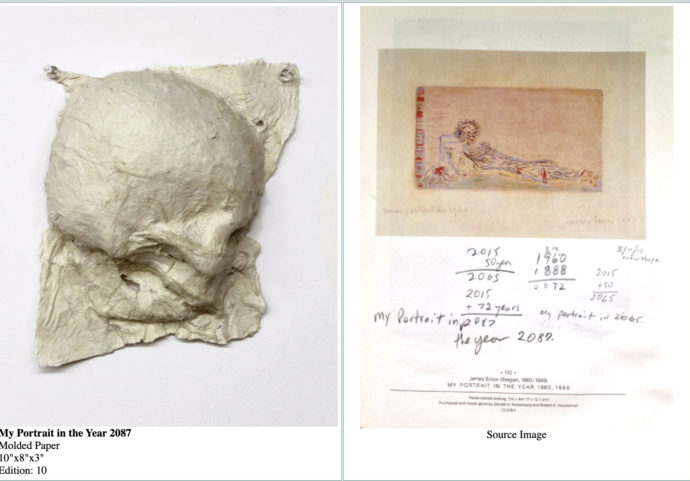

P: Oh, I hadn’t realized that. The last thing I want to mention is from 2014, your My Portrait in the Year 2087. Why did you do that?

A: It’s an appropriation. James Ensor did a small etching in 1888 of himself as a skeleton. He titled it My Portrait in 1960, or some 70 years after he made it. That’s where that idea came from. So I did a portrait of myself as a skull in 50 or 60 years after I made it. That’s what I’m gonna look like. It glows in the dark, by the way, too.

P: Okay, okay. Well, it’s important to actually be comfortable with one’s own mortality. And that’s a hard subject. You’ve come to grips with your own mortality. You can kind of make a semi joke about it, and yet be serious.

A: Yeah, laughing is good. You know laughing represents some kind of an unresolved conflict and it’s discharged by making a joke. It’s a psychological sort of thing that happens. And I’ve been making work really trying to deal with my internal conditions. I do it as an artist. And since I was a doctor, I got special access into places of incredible human experiences.

You know, Scott, I just saw my old teacher, and I say, oh, in an ageist way, because he is 90 and think that people at 90 are falling apart, but he is definitely not. And I went out to see him in Tucson. This is three weeks ago. When I knew Andy and was getting my degree in Fine Arts from the University of Arizona, my draft number was 69. And I was gonna go to Vietnam, unless I could continue my education or go into the National Guard. And so Andy said to me: Eric, you’re always talking about being a doctor. He said: Why don’t you go to medical school? I said: Artists can’t be doctors. And he said: Listen, you’re going to always make art.

I just went over this story with him three weeks ago. I’m sitting across from him in Tucson and telling him this story. I said: Andy, I was sitting across from you and you said go to medical school. If you don’t try, you’ll look at your life and say I should have tried. And so I took science courses, did good enough, wasn’t the greatest. Anyway, I was very distracted. But anyway, I became a doctor. So Andy said: Eric, listen, you’re always going to make prints. You should go have an interesting life. And he said: When you get to be older ( I’m 73 now), he said to me: Eric, you’re going to look back on your life. Your prints will have fallen out of your life like dandruff. And I said: Andy, you know, that’s what’s happened. Scott, you’ve been in my place. I have so much dandruff from my life.

P: (Having been in his studio and seen his life’s work hanging everywhere, I said:) I can attest to that. Thank you so very much!

TO BE CONtINUED

“Making a COVID Bowl with Eric Avery, Part II” will illustrate the entire process.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/making-a-covid-bowl-with-eric-avery-part-1/trackback/