Karl Rössing: Witness to Weimar’s Final Years

Introduction

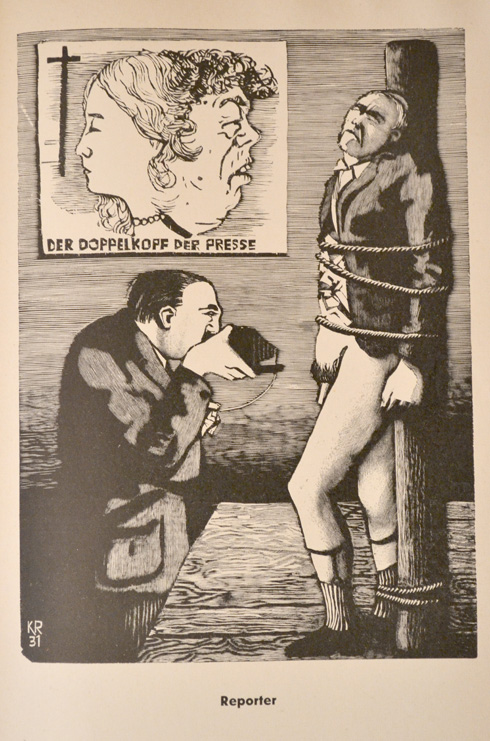

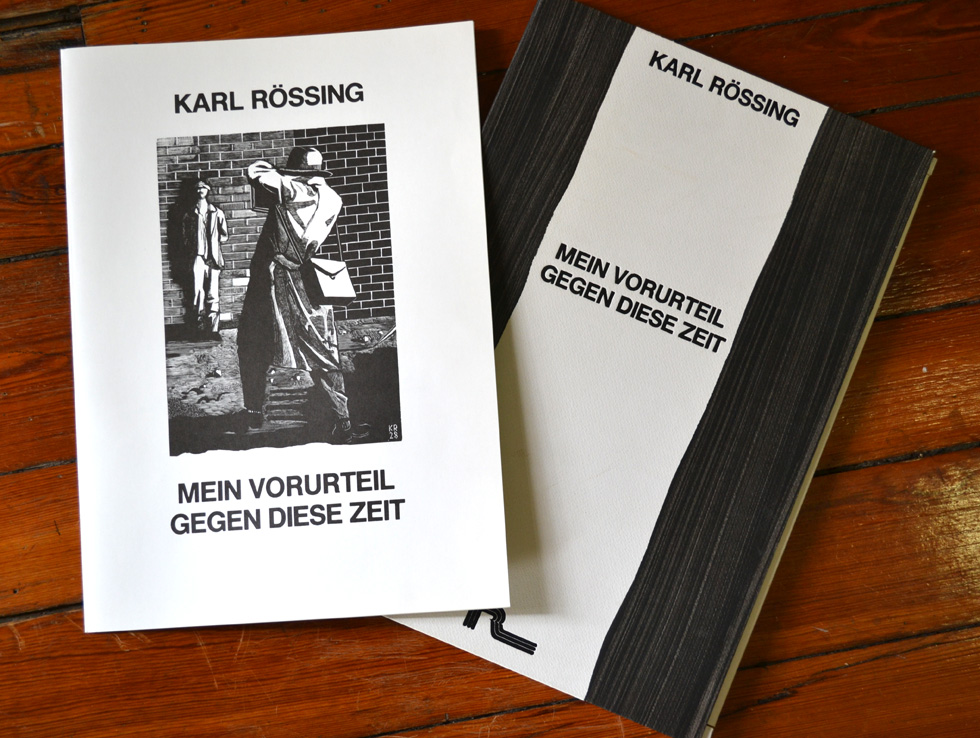

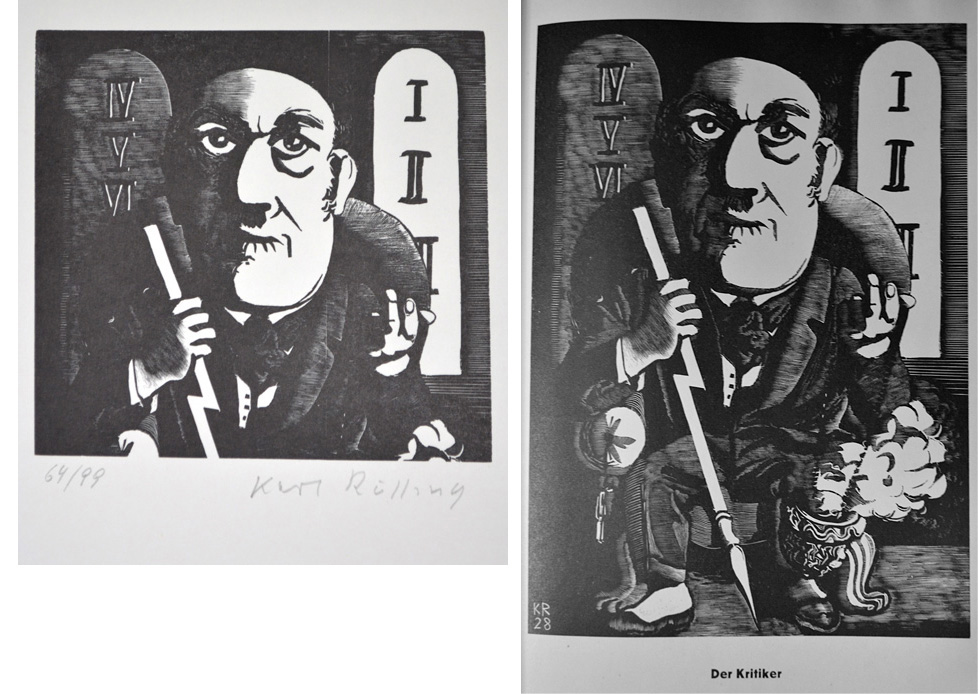

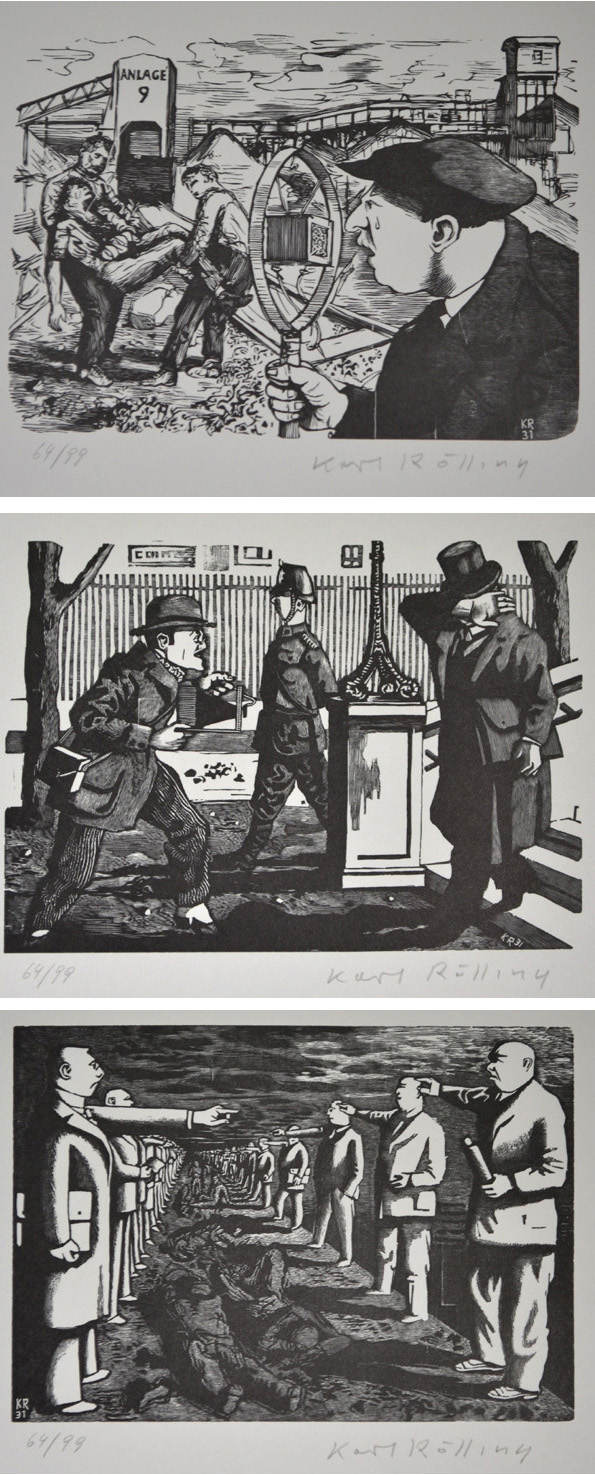

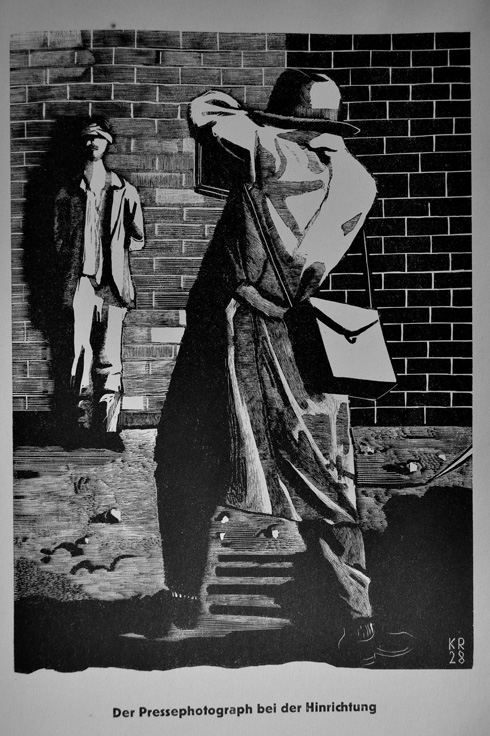

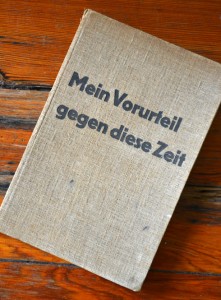

Sometimes eBay can open worlds to you. This is what happened when an Israeli book dealer put Karl Rössing’s 1932 book Mein Vorurteil gegen diese Zeit (My Prejudice Against This Era) up for auction. After a brief introduction by Rössing, the contents were simply 100 briefly captioned wood engravings–all very opinionated, sometimes scathing views of life in the waning years of the German Weimar Republic, which was born in the ashes of World War I (1918) and died with the appointment of Hitler and his Nazi Party to power (1933). And when I mean scathing, I mean scathing. Below is an example. The vignette reads “The double head of the press,” which could well mean the duplicity of the press. Surely the main image shows a “reporter” exhibiting prurient interests while neglecting the imminent execution. So I’m snagged on the book for three reasons: 1) I love books with minimal or no text, 2) I’m taken by wood engravings and 3) Rössing’s uncompromising imagery. For me, his work is right up there with that of the better know German artists Georg Gross and Otto Dix.

In short, I bought the book. Then, thanks to scrolling through listings online at AbeBooks.com, I discover that Rössing (1897-1987) had reprinted 26 of the surviving blocks in a portfolio in 1984. And he signed each plate. While I can’t explain how values are set, I’m happy to report I could afford to buy the set from a German dealer. Some of the plates, like Boxer und Botschafter, show that seams have opened up where the wood blocks had been laminated together. (These open seams were proof that these relief images were wood engravings, not woodcuts.) But most are without fault. None of the plates in the portfolio carry the captions from the book. While the portfolio does have a numbered list of captions, the plates are not numbered. But I could match up the plates with the captioned pages in the book.

My rudimentary German reading skills helped me translate a few of Rössing’s images, like the one shown (which is not in the portfolio). But the meaning of most eluded me. I turned to Oliver Shell, Associate Curator of European Painting & Sculpture at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Last spring Oliver curated a show of German Expressionist art at the BMA. And sure enough, he is fluent in German. I sent him just the 26 images in the book that corresponded to the plates. He graciously translated them and added comments to a few. Then when I thought of presenting the portfolio as a blog post, I asked Oliver to translate Rössing’s introduction–used in both the book and portfolio.

Initially I thought that’s all of the components I needed for this post. But then I began to think that I need to put these plates in context to the times and place where these were made and published. (With few exceptions, each plate bares his monogram and a date (from 1927 to 1931)–the final Weimar years.) And I wondered what was Rössing’s roll in the Weimar Republic and–and this is no little thing–what was Rössing’s link to the Nazi Party. Was Mein Vorurteil gegen diese Zeit in part a denounciation of what Hitler would call degenerate art and artists? Was Rössing making anti-Semitic slurs? Where was he during the war, for instance?

Context for Rössing’s prints

In searching for the fall of the Weimar Republic, I came across the blog Historymike, which included a long post called “The Fall of the Weimar Republic.” (See: http://historymike.blogspot.com/2007/07/fall-of-weimar-republic.html) The blog identified Historymike: “Dr. Michael E. Brooks is a historian, journalist, acrophobe, and geek who writes on a wide variety of topics.” In this post from 2007, Brooks attempts to synthesize a number of cited authors of the Weimar years. He cites a number of reasons that contributed to Weimar’s collapse.

1) A faulty constitution: The Weimar constitution “contained items such as Article 48 – a constitutional provision that permitted the Weimar President to rule by decree without the consent of the Reichstag.” And the constitution is also blamed for providing for proportional representation in the Reichstag and, thus, inherent political instability.

2) A culture of political violence: “The rise of militant extremists such as the NSDAP [Hitler’s part] should be viewed within the context of the Weimar history of political paramilitary forces as a “normal” phenomenon.” A number of parties, not just Hitler’s, employed paramilitary squads.

3) Reaction to new freedoms: Weimar Germany enjoyed unrivaled intellectual, artistic and sexual freedoms, but the bulk of the German population remained strongly conservative. Hitler used “widespread perceptions of decadence and disaffection with modernity as springboards for his anti-Marxist and anti-Semitic philosophies.”

4) Economic instability: “The Weimar government, at various times, faced food shortages, hyperinflation, massive unemployment. …” Inflation became virulent in the early 1920s. The German mark, which traded at 4.2:1 to the dollar prior prior to WW1, rose to 4.2 trillion marks to the dollar by November 1923.

5) The Great Depression: Over 30 percent of working-age Germans were unemployed at the height of the Depression. In short, says Brooks, “The collapse of the German economy created conditions ripe for those on the Weimar political extremes.”

Brief bio

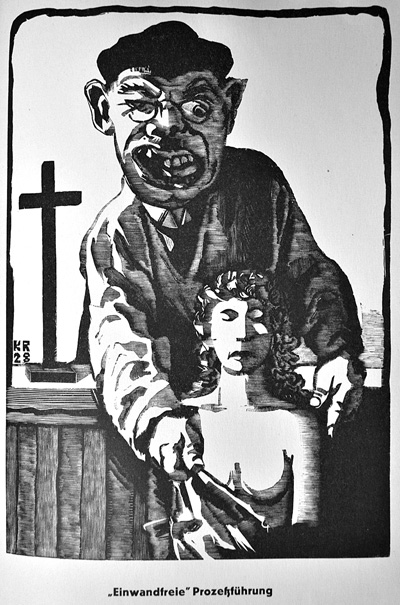

Rössing, of course, was part of that world. His wood engravings were germinated in that world. And into that world came Mein Vorurteil gegen diese Zeit. How it was received at the time, I don’t know. But in trying to learn about Rössing the man, I turned again to online searches. One I found is in English. It’s at artoftheprint.com, run by Canadian print dealers Greg and Connie Peters (http://www.artoftheprint.com/artistpages/rossing_karl_einwandfreteprozessfuhrung.htm). I asked the Peters what was the source of their information, but I haven’t gotten a response. Their Rössing text is used to present the print “Einwandfreie” Prozessfuhrung. The other, a lengthy Wikipedia entry, is in German (http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_R%C3%B6ssing). Of course there are likely to be many authors here. Oliver Shell graciously translated the part of that bio dealing with Nazi era: 1932-1945. I’ll start with text from the Art of the Print site.

A twentieth century Austrian artist, Karl Rossing studied at the Koniglichen Kunstwerbeschule in Munich from 1913 to 1917. His teachers there included Richard Riemerschmid, Fritiz Helmuth Ehmcke and Adalbert Niemayer. He first exhibited his wood engravings in Munich in 1915 at the Graphischen Kabinett Schmidt-Bertsch. During the following years Karl Rossing’s art was included in important exhibitions in Munich (Neue Secession, 1919), Salzburg (1921), Mannheim (Neue Sachlichkeit, 1925), Moscow (1933), London (1937), Dresden (1946), Baden-Baden (1947), East Berlin (1964), Nurnberg (1971), Hamburg (1973) and New York (1974). He also exhibited extensively with his artist wife, Erika Rossing (ne, Glockner, 1903-1977).

In 1921 Karl Rossing began teaching printmaking and illustration at the Folkwangschule in Essen. He became a full professor there in 1926. In the following decade he was teaching at the Staatlichen Hochschule fur Kunsterziehung [Higher State Art School] in Berlin.

Now I turn to Oliver’s Wikipedia translation.

Since 1931 Rössing was supported by the Weimar cultural minister Edwin Redslob who also sought to help him to win commissions. Although Redslob was dismissed in 1933 by the new regime (the Nazis), as late as 1934, there were still officials of the Prussian Ministry of Scholarship, Art, and Education like Alexander Kanoldt who supported Rössing’s appointment as the Docent for the class in Painting and Drawing at the Higher State Art School in Berlin. In 1939 he received tenure as a professor there.

Rössing’s life during the National Socialist period is a mirror of the contradictions of this time. In 1937, the Nazi sensors seized Rössing’s illustrations for Münchhausen as well as his cartoon “Einwandfreie” Prozessfuhrung, some of the few works by him that had made it into museums. Besides, he is mentioned in Wolfgang Willrich’s [a fanatical Nazi artist/author–Oliver’s insert] infamous book The Cleansing of the Temple of Art. That same year, one of his students defamed him. As a result, and under pressure from the director of the art academy (where he taught), Rössing decided to become a member of the National Socialist Workers (NAZI) Party. As early as 1933 he had already sought to become a member of the party but was not registered, and, after he moved to Berlin, he no longer paid his membership dues.

I turn back to artoftheprint.com for comments on “Einwandfreie” Prozessfuhrung , which the Peters translate as: Faultless Litigation or Proceedings and Conduct From from Objection.

Karl Rossing’s original wood engraving “Einwandfreie” Prozessfuhrung is an early representation of the dangers of the rise to power of Adolf Hitler (born, 1889, died, 1945). A fine twentieth-century painter, printmaker and illustrator, Karl Rossing was at the vanguard of that praiseworthy group of concerned artists who recognized the dangerously shifting political and social developments of their country and had the courage to depict it. … Karl Rossing was one of the first artists to criticize Hitler and his followers.

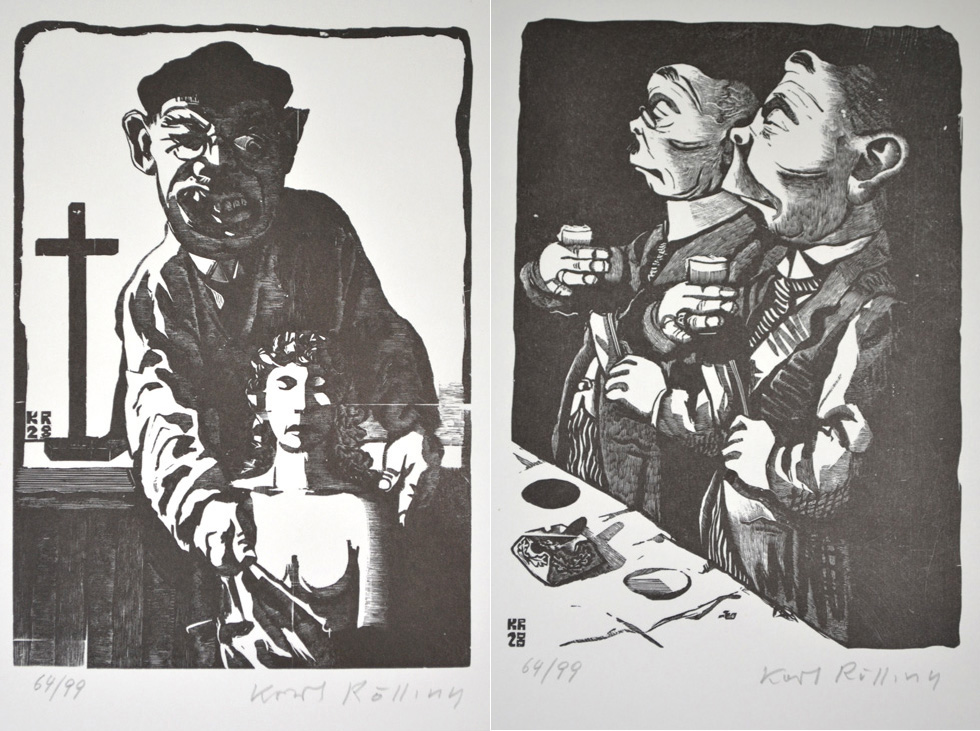

“Einwandfreie” Prozessfuhrung … is an important case in point. Here we are given an early portrayal of Adolf Hitler shortly before he came to power. His atrocities, however, were already known to any open-eyed observer, and Mein Kampf, written by Hitler and published several years before this woodcut [dated 1928], clearly spelt out its author’s intentions. Rossing thus depicts Hitler as a lecherous tyrant disrobing a woman whose closed eyes and posture bear strong affinities to the symbol of justice. The cross on the stand is a vivid reminder of the church’s support for this man. In short (even at this early date) Rossing saw what most of Germany chose to ignore.

Back to the Wikipedia entry.

In 1941, Rössing traveled to Crete under commission of the artist Walter Wellenstein who worked in the Ministry of Aviation (tasked with supplying art) who among other things was responsible for the Schiller Theatre. Theatre Director Heinrich George had found a position there for his friend the former Communist Art Historian, Wilhelm Fraenger, whom he engaged as an artistic advisor. Fraenger, who had himself been fired by the Nazis from his former position in Heidelberg, engaged Karl Rössing as well as his student from Essen the Communist Gunther Strupp.

The motifs in Rössings images were largely contrary to the regime: landscapes, which he brought back from his summer travels to Austria and the southern Tyrolia, as well as pictures of historical themes that had always interested him. At the same time, he tried again and again to offer Goebbels and Goring and even the Cemetery for Fallen German Parachute Soldiers in Crete his graphic works that were critical of the times. [Really odd but Nolde did the same–Oliver’s note]

In 1944, Rössing’s apartment house was destroyed in the bombings. He lost countless works and approximately 1,800 books. Thereafter he and his wife moved to Blankenburg in the Hartz district where his brother Wilhelm lived. That same year he was drafted and obliged to join the war. But, just as in World War I (1917-1918), he also survived this war with only peripheral heavy psychological damage.

Oliver Shell added this note during our email exchange regarding Rössing’s Hitler-era years: “I get the sense that he was opposed to the Nazis, but living and working in Germany in those years and with such political pressures, he had to make a few compromises–probably less than most people who maintained jobs under the regime.”

Mein Vorurteil gegen diese Zeit

The following is the Kierkegard quote and introduction by Rössing used in both his 1932 book and 1984 portfolio (as translated by Oliver Shell):

“A single individual cannot help or save the time in which he lives, he can only express that it is sinking.”

(Kierkegard)

If the author of this picture book for adults also takes on the task of writing its introduction, this is not done in order to strengthen or explain the impression made by the images; any textual addition occurred in the titling of the individual sheets. These titles are such that the pictures must be understandable. What prompts me to add a few words at the outset is my wish to say that, for me, the goal is not to humiliate the ever-recurring bourgeois philistine. I leave that to the philistine satirists of all parties, who will never understand that this figure only plays a statistical role in the larger world theatre and has become thoroughly harmless and no longer needs to be exposed. Today, our task concerns other things, namely to expose the true philistines who break their dummy lances and disguise themselves as defenders of culture and spirit. Today’s culture industry will not rest until it has introduced the “Day of the spirit,” launched with the wake-up call: “I no longer recognize people, I only know clients,” and ending with “and many celebrities were on hand.” Over this cheap market-ground of irresponsibility and spiritual decay, the rags of spiritual conviction, and the speculation that contemporary memory is short-lived, one reads indelible and still red from the bloodshed of the war, the word “Profit.” This, under the art business dealers scarily dispersed view and conception of life, that earnings are paramount, and in order to live well even the honor of the human spirit must be sacrificed, this is what needs to be satirically targeted—not obscenities about the distress of prostitutes, whose profession is far cleaner than that of the responsible editor of today’s media, the press. Those, however, who constantly come to me with the thoughtless argument that critical efforts do not improve the world by as much as hair’s breadth, that such an effort is pointless and superfluous, should give some thought to the statement by Kierkegard with which I began this introduction.

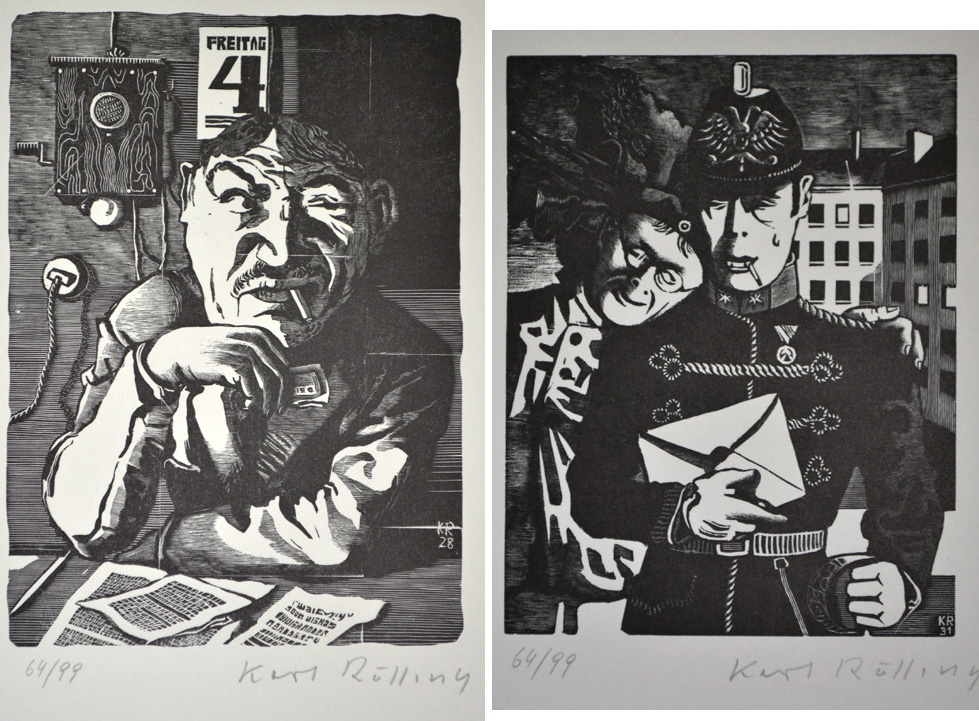

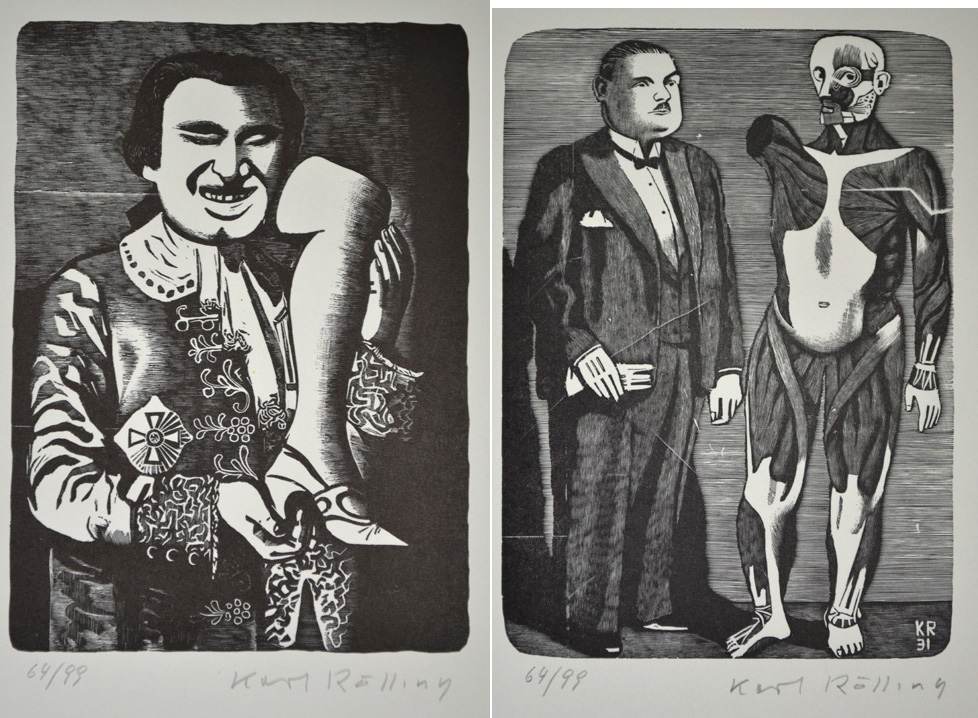

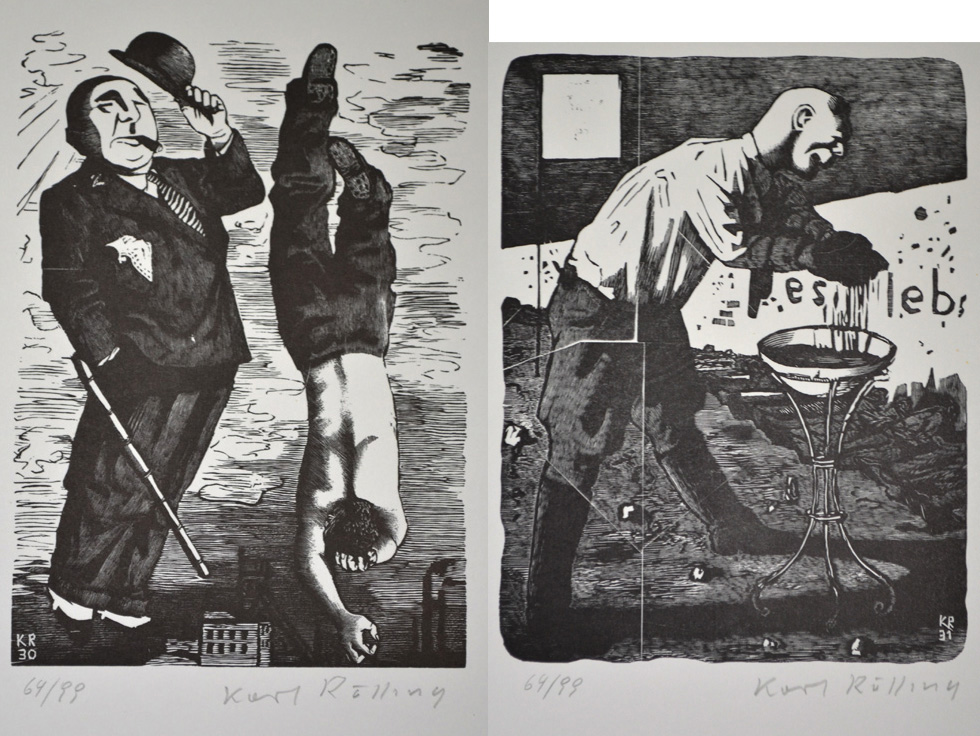

Plates from the portfolio

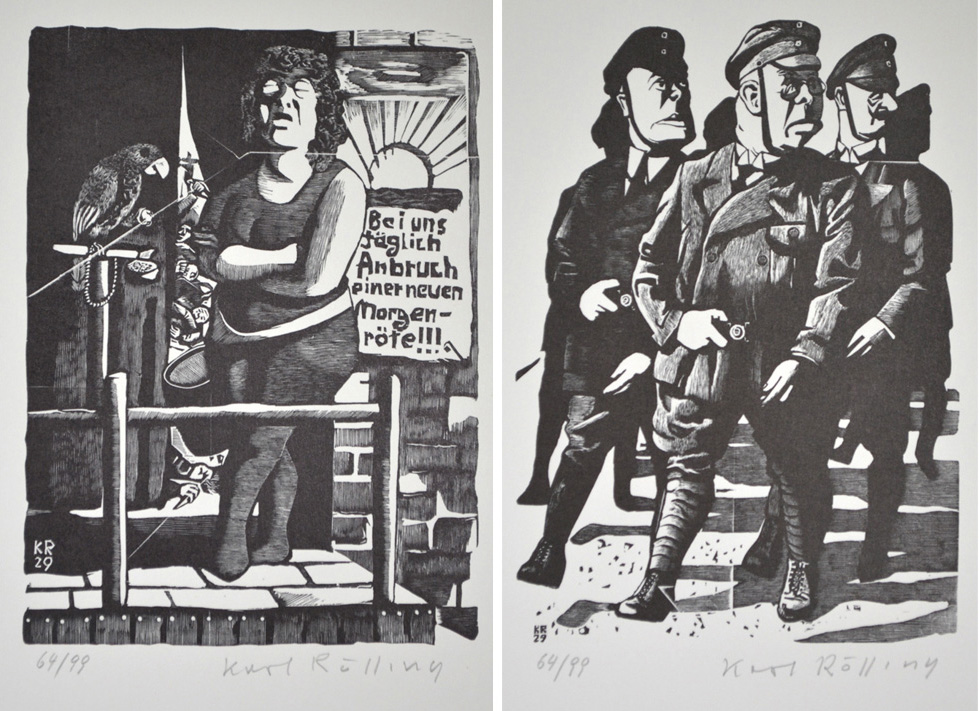

The sequence of these 26 plates follow the portfolio, and they appeared in the portfolio in the same order as they did in the book of 100 plates. I haven’t detected an underlying method that guided Rössing in ordering the book’s plates other than that the vertical plates (81) come before the horizontal ones (19). All of my portfolio plates are numbered 64/99 and signed by Rössing. The titles of each plate correspond to the titles Rössing gave for them in his book. Translations and comments are by Oliver with exceptions noted.

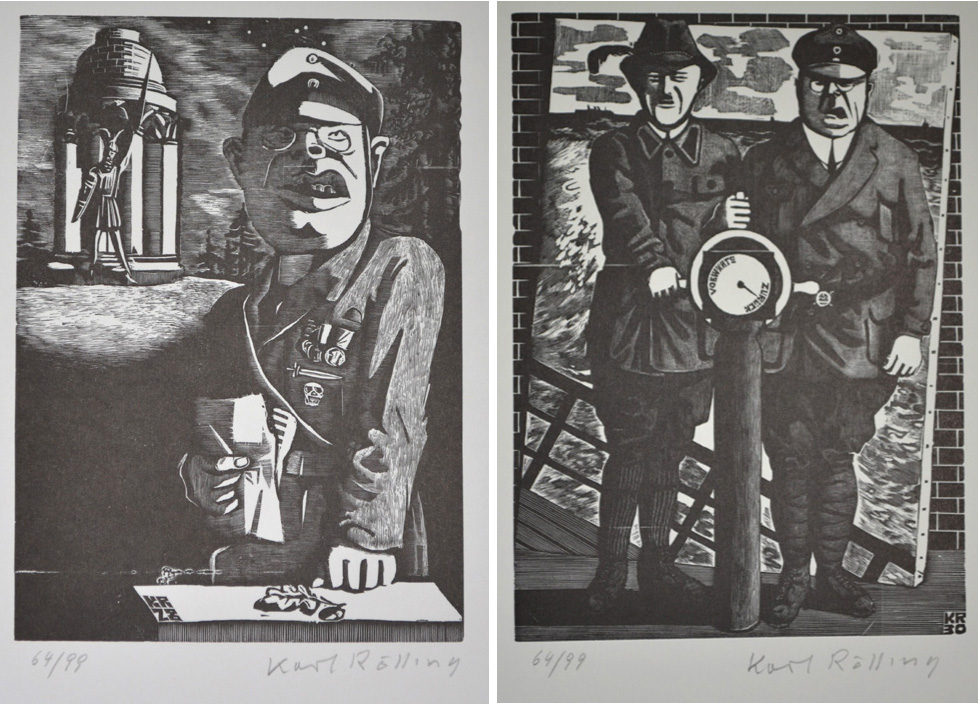

(left) Die Partei – The Politcal Party: “With us every day has a new red dawn!!!” The red may be a jab at leftist or Socialist political parties (Let’s not forget the Nazis presented themselves as “Socialists”), but as the scene of carnage we glimpse through the crack in the curtain reveals, the red also signals some hushed up bloody event.

(right) Die Alte Garde (Und wenn die Welt voll Teufel wär) – The Old Guard (And when the World Was Full of Devils)

(left) Ein Traum im deutschen Märchenwald – A Dream in the German Fairytale Forest: Märchenwald evokes the notion of a fantasy version of German history. The knight and the building in the background seem to refer loosely to medieval fantasy and evoke the burial monument of Theodoric in Ravenna—thus a historical period of Germanic peace and sovereignty is alluded to. Among the brutish German officer’s medals is a death head. The basic conceit is of a contemporary military officer having the delusion of seeing himself as the modern representative of a noble Germanic tradition of medieval chivalry.

(right) Mit Volldampt zurück – Full Steam Backwards: The binnacle says “Forwards” and “Backwards” on it with the arrow pointing on the backwards indicator. The left figure seems to be a cartoonish yet not exact depiction of Hitler. The other figure evokes Paul Von Hindenburg (who swore Hitler into power in 1933) but who is missing his characteristic mustache.

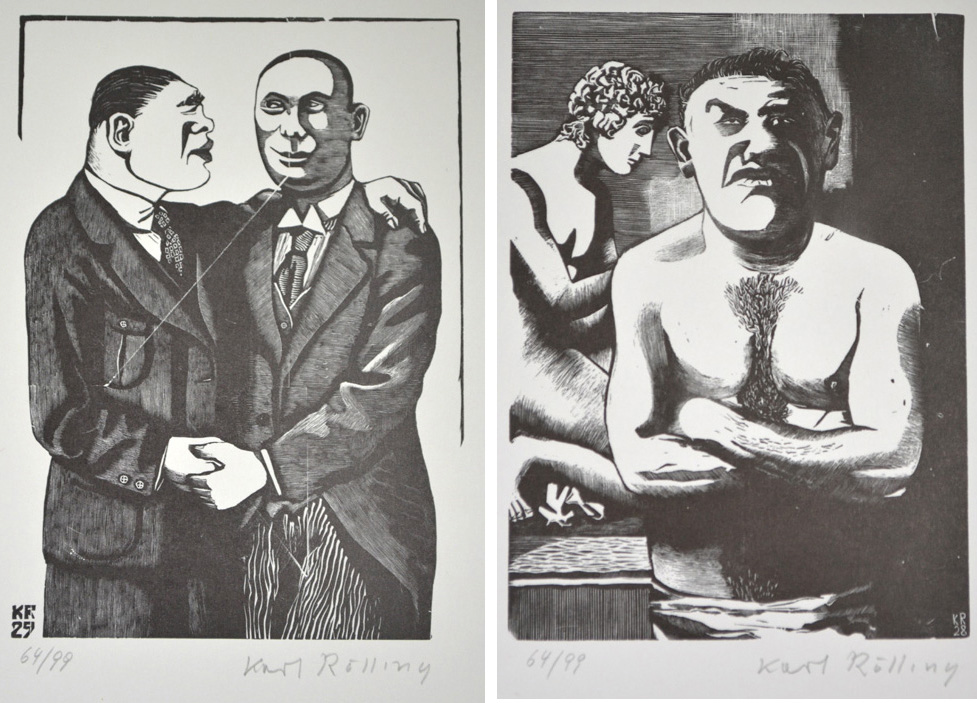

(left) Boxer und Botschafter – The Boxer and the Ambassador

(right) Olympiasieger – Victorious Olympian: I think that Rössing is contrasting the Greco-Roman idealized statuary-type seen in the background with the brutish proletarian physiognomy of the contemporary strongman in the foreground.

(left) Schönheitskönigin – Beauty Queen

(right) Revue und Theater – Burlesque and Theatre: (my comment) Once again Rössing is comparing the Greek origin of theatre to the grotesque state of stagecraft of his day. A classical laurel wreath is about to be stepped upon.

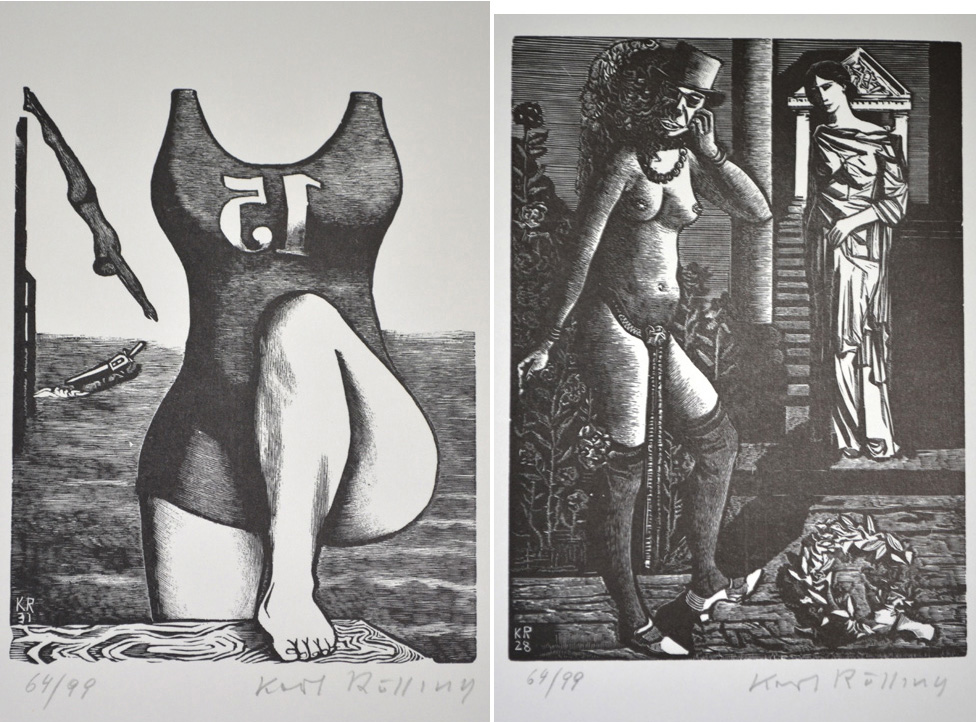

The portfolio included Der Kritiker – The Critic (left) despite the loss of the bottom third as shown from the book (right). (My comment) With the Commandment tablets behind him, an incense burner suspended from his left hand, and a lightning-bolt/pen in the other hand, this man is, I suspect, using religion to justify his critical positions.

(left) “Einwandfreie” Prozessfuhrung – Unimpeachable Judicial Process : Shell’s translation carries the same sense as that in Art of the Print.

(right) Vivat Academia – Long Live the Academy

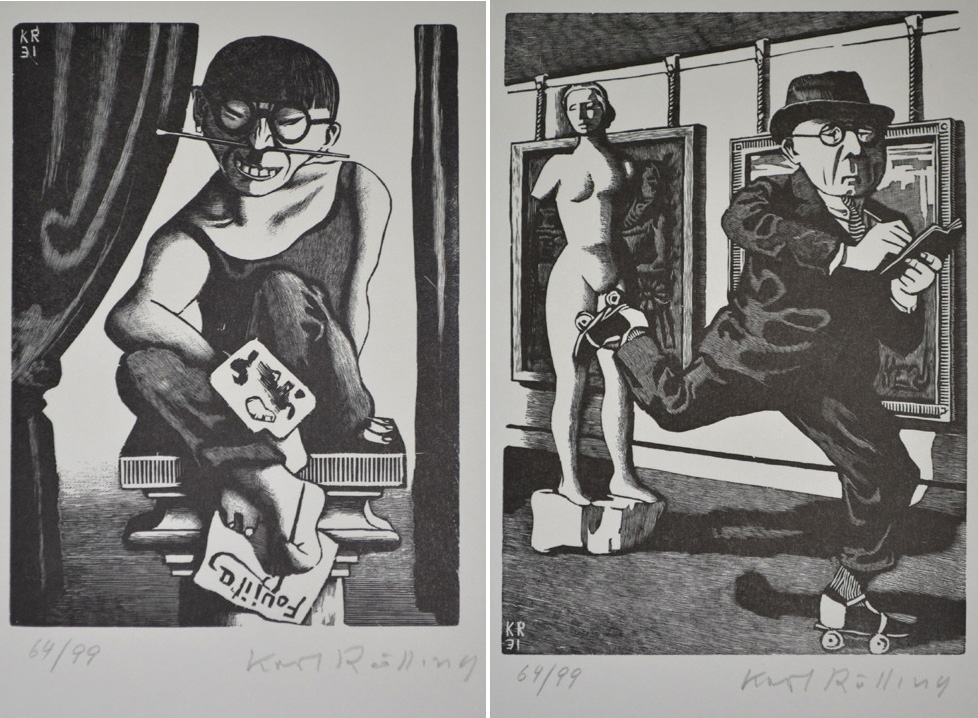

(left) Foujita, Leibling der Laien – Foujita, Darling of the Drunks [or fools]: By 1933, School-of-Paris artist Tsuguharu Foujita (1886-1968) was welcomed back as a minor celebrity to Japan, where he stayed and became a noted producer of militaristic propaganda during the war. For example, in 1938 the Imperial Navy Information Office supported his visit to China as an official war artist. Foujita left Japan after the war. Yasuo Kuniyoshi, a Japanese Issei [first-generation American] painter who worked for the United States Office of War Information during WWII, showed opposition to Foujita’s art show at the Kennedy Galleries. Yasuo called Foujita a fascist, imperialist, and expansionist.

(right) Der Ausstellungkritiker – The Exhibition Critic: Obviously a man on the go!

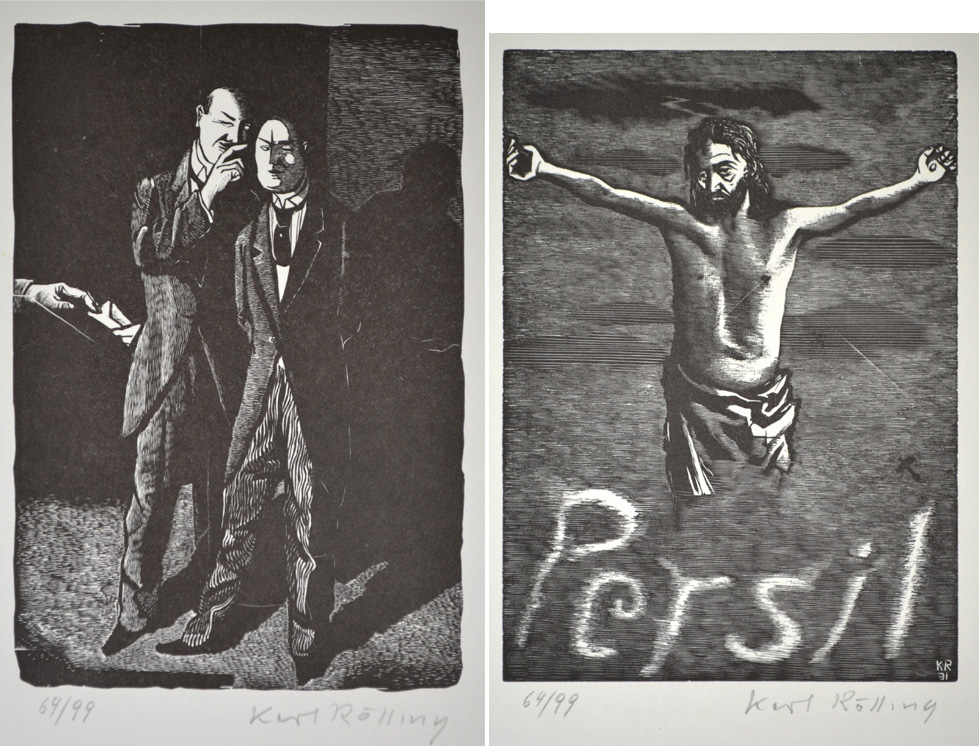

(left) Die Diplomaten – The Diplomats

(Right) Kunst der Werbang (“Herr, vergib ihnen, denn sie wissen night, was sie tun.”) – The Art of Advertising: “Lord, Forgive Them for They Know Not What They’ve Done”: “Persil” is a German laundry detergent.

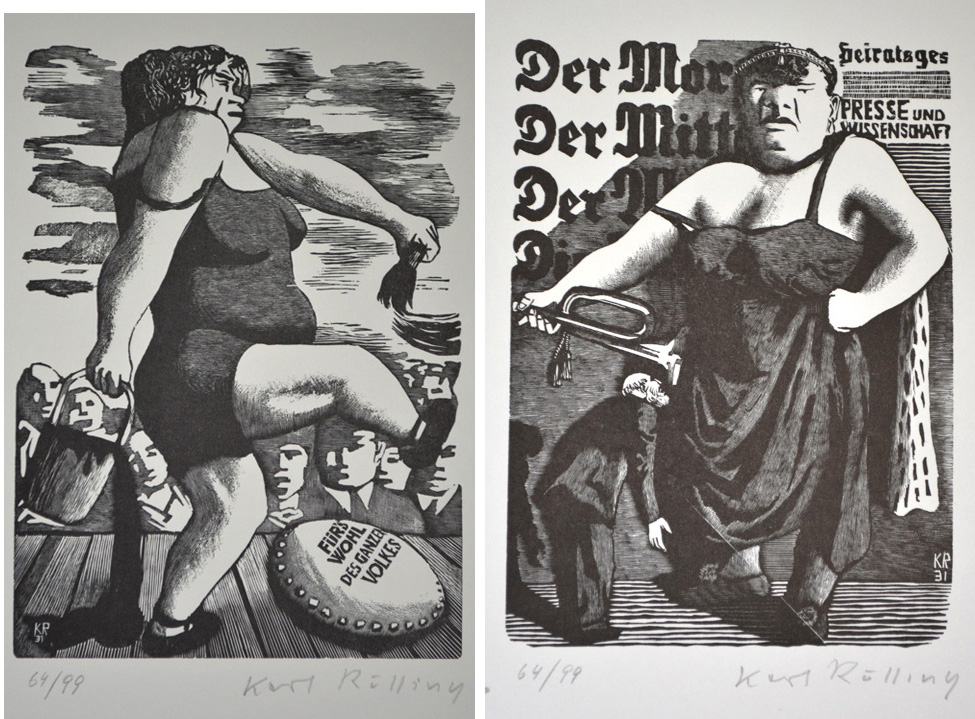

(left) Die Öffentliche Meinung – The Public Opinion: The words on the odd cushion or drum read: “For the good of the whole race.”

(right) Man verbeught sich vor der Presse – One Bows Down to the Press: At left we see the partial headlines of the “Morning Edition,” the “Mid-day Edition” and presumably the “Evening Edition.” At right on top there are the “Wedding Announcements” and below “The Press and Scholarship.”

(left) Erpressungsjournalist – Blackmail Journalist: Perhaps the wiring behind the figure alludes to wiretapping.

(right) Liebe und Trompetenblasen – Love and the Blair of Trumpets – Some enigmatic critique of militarism.

(left) Das Lied von der Bembergseide oder Kitsch mit Weltruf – Song of the Bembergseide or kitsch with a worldwide reputation (Google translation): Bemberg (or Cupro) is a special brand of fabric used for lining in only the best suits. It was invented in Germany in 1918 by J. P. Bemberg. (from us.suitsupply.com. See: http://us.suitsupply.com/en_US/bemberg.html)

(right) Konfektion und Anatomie – Outfitted Dress and Anatomy

(left) Irtdisches Wohlergehen – Earthly Well-Being: The bowler hat and white socks make it plain that this is the bourgeois capitalist versus the shirtless worker.

(right) “Ich habe es night gewollt” – “I Did Not Wish It”: (my comment) With bodies lying below a bullet-pocked wall, a booted man washes his hands in blood.

(Top) Der Tod im Dienste des Rundfunks – Death in the Service of the Broadcast

(middle) Gesetzlich erlauber Überfall – Legally Sanctioned Robbery

(bottom) “Dort steht der Schuldige!” – “There Stands the Guilty One”

(This image from the book is the same as on the title page of the portfolio) Der Pressephotograph bei der Hinrichtung – The Press Photographer at the Execution: (my comment) Instead of recording the execution, the photographer almost appears to be on the firing squad. However, note the shadows of the barrels of rifles between the photographer’s legs.

ADDENDUM

I welcome any comments and am willing to amend this blog. You may well have alternative explanations for the fall of the Weimar Republic, additions or changes to Rössing’s bio or alternate translations and interpretations of the individual plates.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/karl-rossing-witness-to-weimars-final-years/trackback/

Thank you for the in depth coverage of Karl Rossing and his works. I came across Rossing through the book by Frtiz Reuter which he illustrated and signed – Hanne Nüte un de lütte Pudel .

Excellent and VERY useful. Many thanks for the nice work done. .