John Sloan: Anatomy lesson with friends

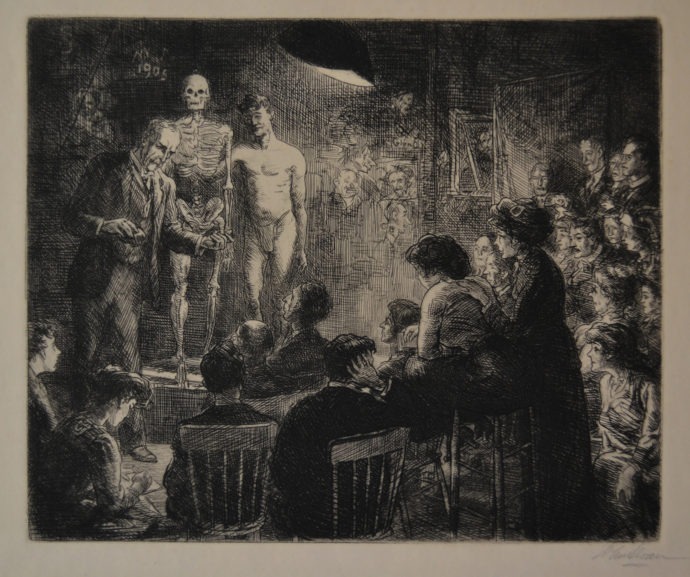

John French Sloan (American, 1871-1951), “Anshutz on Anatomy,” etching, 1912, plate 7 1/2″ x 9″ (191 x 229 cm) This print is #155 in Peter Morse’s “John Sloan’s Prints.” While the intended edition was 100, Morse listed only 80 as being printed. He said the plate was copper, had been steel-faced (now removed) and was part of the John Sloan Trust at the Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE.

Introduction

When I started out as a print collector some 40 years ago while working part time on the copy desk of the Baltimore Sun newspaper, owning an etching by John Sloan, a prominent member of “The Eight” group of early 20th-century New York artists, was wishful thinking. The cost of his prints far exceeded my discretionary budget. And that essentially remained true even as the maximum that I was willing to pay for a single print grew some 15 times from its initial $100 limit. While for decades I didn’t shell out for one of his prints, I did eventually (in 2014) secure a copy of Peter Morse’s “John Sloan’s Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Etchings, Lithographs and Posters” (1969, Yale University Press). Having a comprehensive print-makers reference library was almost as good as having the prints themselves. Owning the book allowed me to witness his immense print output–over 300 prints from 1888 to 1949. And as inevitably happens when learning an artist’s printmaking oeuvre, I gravitated to a few of Sloan’s prints as the ones I’d like to collect “if only” the optimal opportunity arose.

That opportunity (to add a Sloan print to my collection) happened last March at a sale by Rachel Davis Fine Arts, an auctioneer in Cleveland. It wasn’t among the items I intended to bid on, but when I lost out on a print that came up for bid before the Sloan, I bid on his Anshutz on Anatomy on the off chance I could win it.

Anshutz on Anatomy

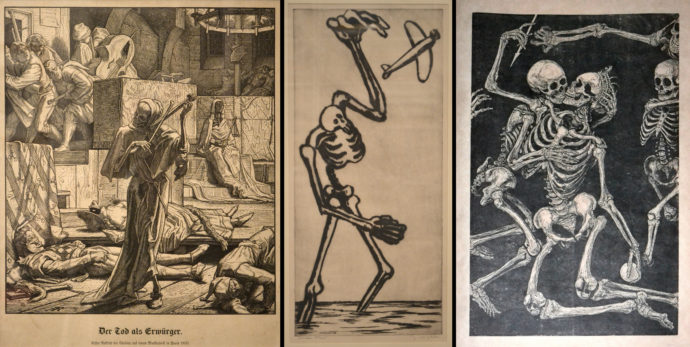

I was attracted to this print for several reasons. For one I have a thing for skeleton imagery. Below are three prints from my collection.

(From L to R) Gustav R. Steinbrecher’s wood engraving (after Alfred Rethel) “Der Tod als Erwunger,” 1851; Edward Hagedorn’s drypoint “Perilous Flight,” 1938; and Tru Ludwig’s woodcut “The Exposure of Luxury,” 2012

And in the bedroom the theme of the prints hanging there is anatomy:

(From L to R) James Allen’s etching “The Accident,” 1934; Cecil Buller’s wood engraving “Song of Solomon, Chapter 7, Verses 6-7,” 1929; and Emil Ganso’s wood engraving “Self Portrait with Nude,” 1930.

BUT the primary reason was that Anshutz on Anatomy tells a great story about American art and art-making in the early 20th century. The print is both a homage to Thomas P. Anshutz, a well respected anatomy lecturer, and a “who’s who” of Sloan’s influential circle of friends.

The print from 1912–the year Anshutz died–commemorated his 1905 visit to New York. Stephen Coppel in the book “American Prints: From Hopper to Pollock” ( Lund Humpheries, 2008) wrote: “In 1905, Sloan’s teacher, Robert Henri, invited their old teacher from Philadelphia, Thomas P. Anshutz, to the New York School of Art to give a series of lectures on anatomy.” (Sloan attended Anshutz’s Antique Class in 1892 and 1893.) For his entry on Anshutz on Anatomy, Morse relied heavily on comments Sloan made in 1946 in a catalogue for an exhibition at Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH. There he quoted Sloan as saying: “Tom Anshutz, our old teacher at the Pennsylvania Academy [of the Fine Arts], gave anatomical demonstrations of great value to art students. Modeling the muscles in clay, he would fix them in place on the skeleton. Those present in this etched record of the talk in Henri’s New York class include: Robert and Linda Henri, George Bellows, Walter Pach, Rockwell Kent, John and Dolly Sloan.”

Morse also quoted a letter Sloan wrote in 1936 to a Dr. Frederick T. Lewis where he says that Anshutz taught at the Pennsylvania Academy for over 25 years and that Anshutz was a “great friend of Thomas Eakins and his work was of a kindred sort. Eakins is now recognized as one of our great masters. Anshutz was a great teacher. Henri, Glackens, and other notable painters studied with him. His talks on anatomy were repeated several times each term at P.A.F.A. and were the best means I ever heard of for giving an artist an idea of essential bone and muscle structure.”

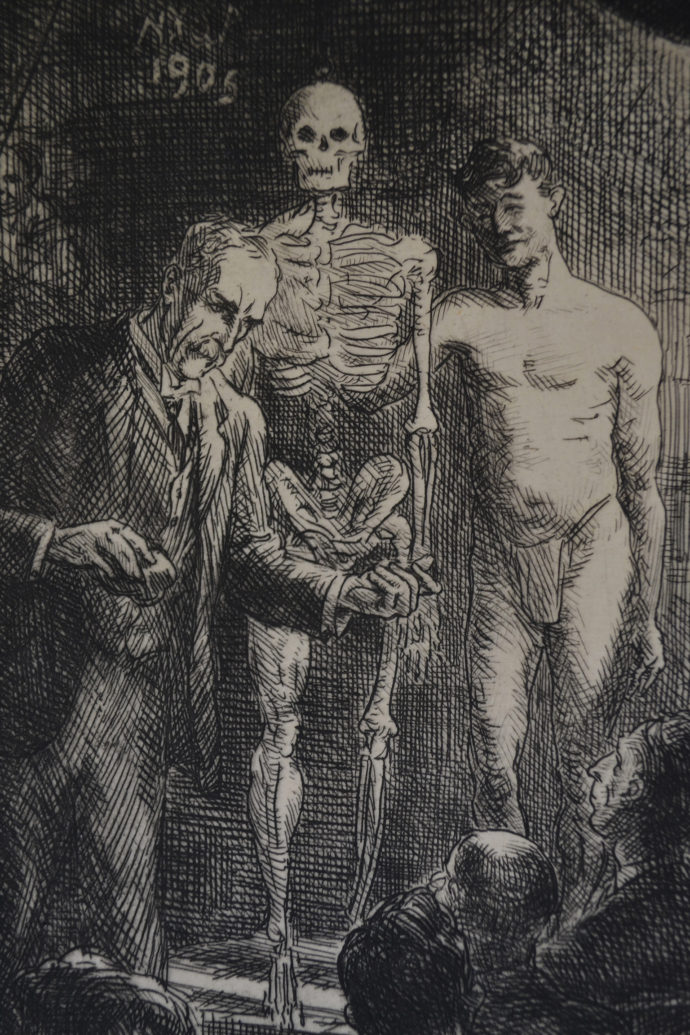

Coppel described the scene. “Anshutz holds a lump of clay which he will model onto the skeleton in order to demonstrate musculature; the live model stands by for comparison. All faces turned towards the teacher, only the empty sockets of the skull look directly towards the viewer.” Note how the skeleton’s leg closer to Anshutz has been shaped with clay. If you look closely near Anshutz’s head, you can see that part of the rib cage had also been modeled with clay.

Because the print was made the year Anshutz died, Coppel said the print served as a memorial to him: “The prominent skeleton stands as a momento mori.”

Anatomy lesson audience

Attending the 1905 Anshutz lecture in New York were a number of artists who like Sloan began their careers in Philadelphia and soon gravitated to New York. Many like Sloan had supported themselves as illustrators for Philadelphia newspapers. In David W. Scott’s essay “John Sloan: His Life and Paintings” in the book John Sloan: 1871-1951 (Scott and E. John Bullard, 1971, Boston Book & Art Publisher, Boston), he wrote: “Beginning in 1895, Sloan’s friends–including Henri, [William] Glackens, [George] Luks and [Everett] Shinn–began leaving Philadelphia, eventually settling in New York…. In the spring of 1904 he [Sloan] went to New York to try to earn his living as a free-lance illustrator.”

As the more senior artist of the group of former Philadelphians, Robert Henri became the de facto leader/spokesman of the group. Scott wrote:

Juries disagreed over the merits of the work of painters of the Henri circle, and on several occasions the painters suffered complete rebuffs, while on others they found their work ‘skied’ or hung in obscure corners. Though friendly critics praised their freshness of approach, hostile reviews attacked them for lack of finish, vulgarity and unhealthfulness (that is lack of conventional beauty).

It was after a particularly sharp disagreement with members of a National Academy jury on which he served that Henri announced, in the spring of 1907, that he and his friends would hold an exhibition in the Macbeth Gallery in February, 1908. The old Philadelphia gang–Henri, Sloan, Glackens, Luks and Shinn–was joined by Arthur B. Davies, Maurice Prendergast and Ernest Lawson. The newspapers dramatized the announcement by reporting that The Eight (as they were dubbed) was challenging the Academy, though the artists themselves regarded their venture as an attempt to broaden exhibition opportunities, not as a break with the Establishment….

In 1910 Sloan again joined with members of the Henri group (including some of the promising Henri students) in staging the Exhibition of Independent Artists, which caused a sensation even surpassing that of the Macbeth show. After that venture, the leadership of the more advanced art movement slipped from Henri personally. In the case of the next major independent exhibition, the Armory Show of 1913, Arthur B. Davies became the principal organizer. Sloan helped hang the show and was represented in it, but his role was in fact relatively minor.

Morse said that Sloan’s etching Anshutz on Anatomy was exhibited at the Armory Show.

The reason for the including the above paragraphs was to illustrate how tight a group was Henri’s circle and Sloan’s part in it. No wonder that Sloan would commemorate Anshutz’s lecture with portraits of many fellow artists.

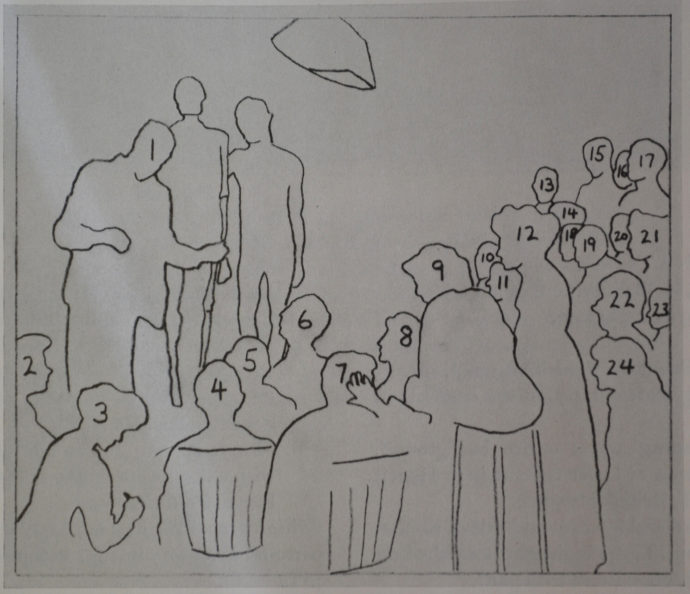

Morse provided this diagram to help identify some of those represented. Of course #1 was Anshutz. Morse indicated that #6 was Walter Pach, #10 William Glackens, #13 Maurice Prendergast, #15 George Bellows, #17 John Sloan, #19 Robert Henri, #23 Dolly Sloan (Sloan’s wife) and #24 Linda Henri (Henri’s wife).

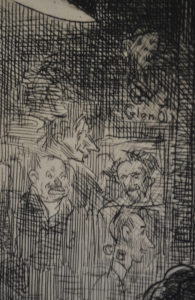

Morse wrote: “Alexander Calder wrote me that he was unable to identify his father, A. S. Calder, in the print, ‘unless he is 4 or 7–but it’s only a guess.’ Rockwell Kent studied the print, confirming some of the other identifications, but did not see his own portrait. ‘We used to paint all over the walls of the studio,’ he added. ‘and Sloan shows some of the paintings in his etching. The one bearing the initials “GB” is probably someone’s caricature of Bellows at the time. The one with “Glen O” under it is definitely Glen O. Coleman.’ I am most grateful to both men for their help.”

Below is a detail of the top center (to the right of the male model) of Anshutz on Anatomy showing the graffiti that Rockwell Kent referred to.

End Note

As mentioned in the caption for the entire image of Anshutz on Anatomy that tops this blog post, its copperplate is part of the John Sloan Trust at the Delaware Art Museum. The museum devotes a page of its website to its Sloan holdings (https://www.delart.org/collections/john-sloan/about-john-sloan/). There it states:

“The Delaware Art Museum is the primary repository for the art and archival collections of American artist John Sloan. The Museum’s permanent collection contains more than 2,600 works of art by Sloan, and the Museum’s Helen Farr Sloan Library and Archives houses more than 300 boxes and drawers of archival material related to the artist. Please use the links below to explore our holdings.

“The Museum received much of this material through the generosity of the artist’s widow, Helen Farr Sloan.”

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/john-sloan-anatomy-lesson-with-friends/trackback/