Interpretive Wood-Engraving: interview with its author

This is Part 2 of my blog on late 19th-century American wood engravers. Please read the first part at: http://www.scottponemone.com/new-school-wood-engravers-forgotton-19th-century-celebrities/

I’m a late-comer to William H. Brandt’s 2009 book Interpretive Wood-Engraving: The story of the Society of American Wood-Engravers, Oak Knoll Press, New Castle, DE. But thanks to, first, an eBay posting, then to a sale of books at the website of the Old Print Shop in New York (http://www.oldprintshop.com/), I’m no longer in the dark about this important episode of American wood engraving. (Once again see Part 1 of this blog to find out what Bill’s book has to offer.) And thanks to Robert K. Newman who answered the phone when I placed my order for Bill’s book. (Last spring Robert was kind enough to grant me permission to photograph at the Capital Print Fair, which resulted in my blog on print dealers: http://www.scottponemone.com/print-dealers-where-would-i-be-without-them/ ) When I told him what book I sought, he enthusiastically endorsed my choice. He knew the author very well, it appeared.

I literally gobbled the book up when it arrived. A day later I emailed Robert asking for contact info on the author. Bill Brandt, he assured, is a person I would enjoy talking to and holding an email interview with. Soon the connection was made. The following is the interview.

Interview with William Brandt

Is your own collection principally of these American New School engravers, their proofs and publications of the period?

Wood engravings constitute but one segment of my collection. I have many wood engravings by members of the Old School as well as the New School plus many recent wood engravings. Beyond that I have lots of etchings, metal engravings, lithographs, serigraphs, paintings, bronzes, etc. While the central focus of the collection has been Art of the American West, opportunities to collect in other fields have been too much to resist.

Can you give me a rough guess as to how many signed proofs you have?

At least several dozen. Of Henry Wolf, I have 20 signed and on Japan tissue plus 6 signed and on wove paper. There is a book The Art of the American Wood Engravers by the English writer Phillip G. Hamerton that contains forty signed engravings on Japan tissue by various American engravers. Signed proofs by Timothy Cole number about 35; then there are signed proofs by Juengling, Closson, Wolf and others. The total exceeds a hundred.

And was there a chief source for them?

No, they came from many places: Rona Schneider, The Allinson Gallery of Storrs CN, The Lakeside Gallery of Three Oaks, MI, The Veatchs Arts of the Book of Northampton, MA. When dealers , librarians, and museum people find you are doing a worthy project, you get lots of leads and lots of help.

In the Enemy’s Country by Frank French after Gilbert Gaul. (Photographed from the SAWE book, not one of Brandt’s signed proofs.)

Do you have many of the signed proofs from the exclusive edition of SAWE Engravings on Wood book?

Only five. In the Enemy’s Country by Frank French after Gilbert Gaul (2 copies). This print was in my collection for 20 years before I started work on the book. When I bought it, it so intrigued me that I hung it near the mantle-piece and kept a magnifying glass there so I could admire it whenever I wished: the lonesome magnificence of the landscape, the tension of the horse and rider, the twists in the piece of halter rope hanging down between the reins. It was not until much later that I learned the significance of the embossed gold emblem of the Society of American Wood Engravers on the mat.

Plus, The Roadside by Henry Wolf after R. Swain Gifford; Miles Standish’s Challenge by Frank H. Wellington after E.A. Abbey; and A Difference by F. S. King after E. H. Blashfield.

Which experts did you rely on?

The main expert I relied on is no longer living: Elbridge Kingsley (1842-1918) joined the Society of American Wood Engravers soon after it formed and played an important role throughout its existence. He left behind a most informative autobiographical manuscript written by hand but available from the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian Institution in microfilm form. It provided the basis for virtually all that I did. Fortunately, Kingsley was interested in other members and worked with some of them personally.

Can you succinctly describe the difference between the style of William James Linton and that of the American new school of engravers?

Linton forbad the use of photography whereas members of the New School considered it a routine necessity in transferring images to the wood block. When Timothy Cole was in Europe he is said to have photographed the old masters onto the block and then sat with his back to them while observing the old master painting in a mirror. Linton forbad the use of cross-hatching or stippling. One way to distinguish an Old School engraving from one of the New School is to look at the atmosphere in the image. If it’s Old School, there will be parallel lines only and they will be horizontal. If the work is New School, you will find cross-hatching.

Practitioners of the Old School felt free to “make improvements” in the design of the artist whose work they were interpreting. New School engravers took pride in faithful and accurate interpretation.

In the Harbor, original wood engraving by Elbridge Kingsley, 1889, 16 7/8″ x 11 3/4″. (From my collection, not Bill’s)

How frequently did these American innovators do original wood engravings? Was Kingsley chief among those who did their own images?

Kingsley said he thought he did about five times as many originals as other members of SAWE. That would be exclusive of Anna Botsford Comstock who made wood engraved illustrations for her husband’s (John Henry Comstock) textbooks about insects. Kingsley caused a small uproar when he did an original wood engraving on a block direct from nature. It was hard for many to believe he had just taken a block into the woods and engraved it without first drawing on it. One of Kingsley’s originals won a gold medal at the Paris exposition of 1889.

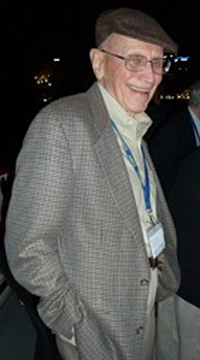

Egypte–La Panique D’Alezandre, August-Louis Lepere (French, 1846-1918), 8 3/8″ x 12 3/8″ (my collection)

Was the Frenchman Auguste-Louis Lepere known to and appreciated by the American interpretive engravers?

A good question to which I do not know the answer. He’s not mentioned in the references I read but probably should have been. I have seen some of his work and considered it to be of good quality. But there was only one Lepere whereas there were many American wood engravers of equal or superior skill.

And finally (for now) do you think your book has placed the interpretive wood engravers in an improved light art historically? Has there been or will there be an exhibition of their work?

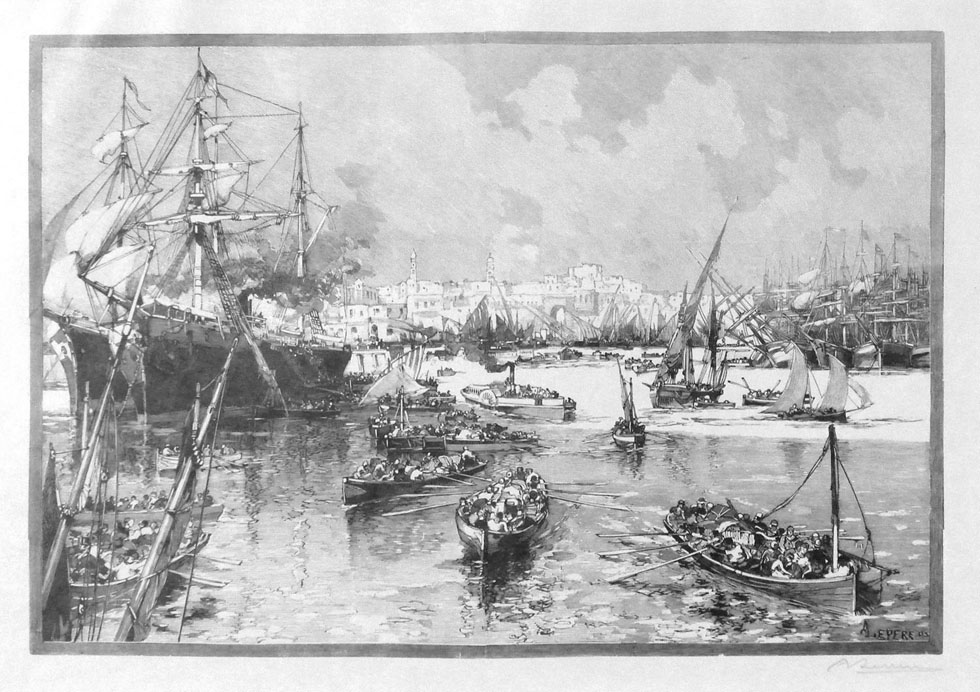

It is my fond hope that my book has placed the interpretive wood engravers in an improved light historically. After all, theirs was the only kind of American art that was considered best in the world at that time. The last major exhibition I can think of was at the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition at San Francisco in 1915. There, where etchings and wood engravings occupied the same category, Henry Wolf won the Grand Prize ahead of luminaries such as James A. M. Whistler.

There are no plans I know of for a future exhibition of their work. The small size of most of their work makes museum exhibitions difficult. Perhaps the most appropriate venue would be something like a TV special on Public Broadcasting. There exists a brief documentary showing Timothy Cole engraving one of his later works.

Harmony in Green and Rose: The Music Room, wood engraving based on a Whistler painting, engraved Henry Wolf (American, 1852-1916), 6 3/8″ x 4 3/4″. (my collection)

And what do you think of the American wood engravers who seem to craft their images as skillfully as the interpretive engravers? Did they keep alive the spirit of the latter group?

No, I think they did not keep that spirit alive. They may be as skillful, but they are transmitting only the meanings of the image they have conjured. Whereas the translators had to convey the feelings of another artist at a much reduced size and with only one color–black. I think they did so successfully.

In the latter part of the 19th-century, the famous French artist, Jean Leon Gerome, came to New York and visited the offices of Century Magazine. He asked to see proofs of the wood engraved interpretations of some of his paintings by Henry Wolf. After looking at them he said “They are beautiful. Mr. Wolf knew better than my brushes what I wanted to do.”

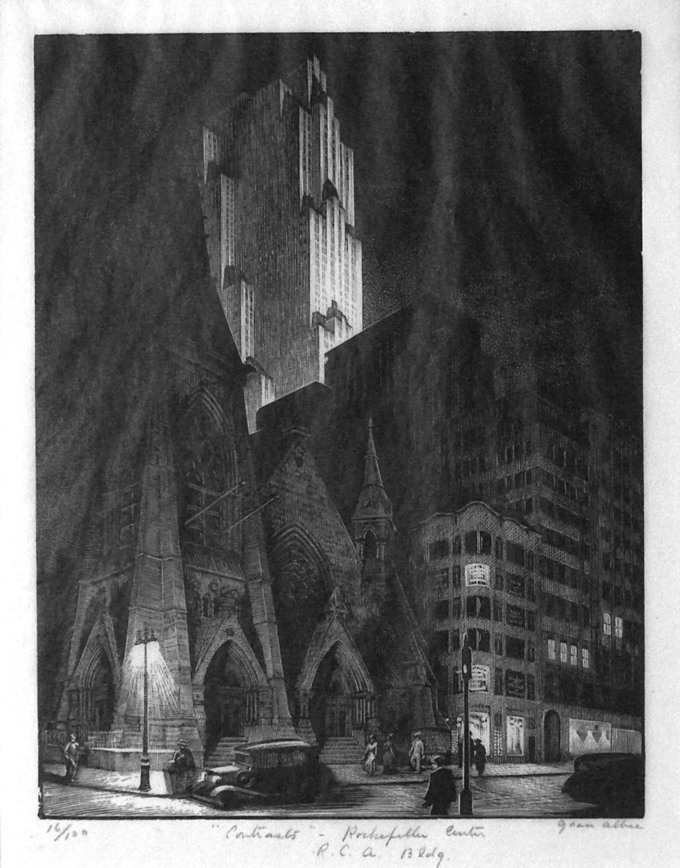

Contrasts – Rockefeller Center R.C.A. Bldg, Grace Albee (American, 1899-1985), 1934, 7″ x 5″ (my collection)

Let me rephrase the question. Did 20th-century wood engravers like Grace Albee learn from the New School and adapt New School technical advances for their own purposes? In other words, could they have done their work so skillfully had the New School not come before them?

I have looked at several 20th-century wood engravings that I have: Paul Landacre, Letterio Calapai, Bernard Brussel-Smith, Emil Ganso, Asa Cheffetz, Barry Moser, etc. My conclusion is that their work in general is not as fine as that of the New School. But it didn’t need to be. The new school had to do very fine work if they were to transmit the ideas of the artists whom they translated. The 20th-century engravers had only to do what they felt necessary to transmit their own ideas. I think the 20th century engravers would have done what they did regardless. Did they feel more free because of the New School? Well, maybe, but I think they would have done exactly as they have done even if the New School had not existed.

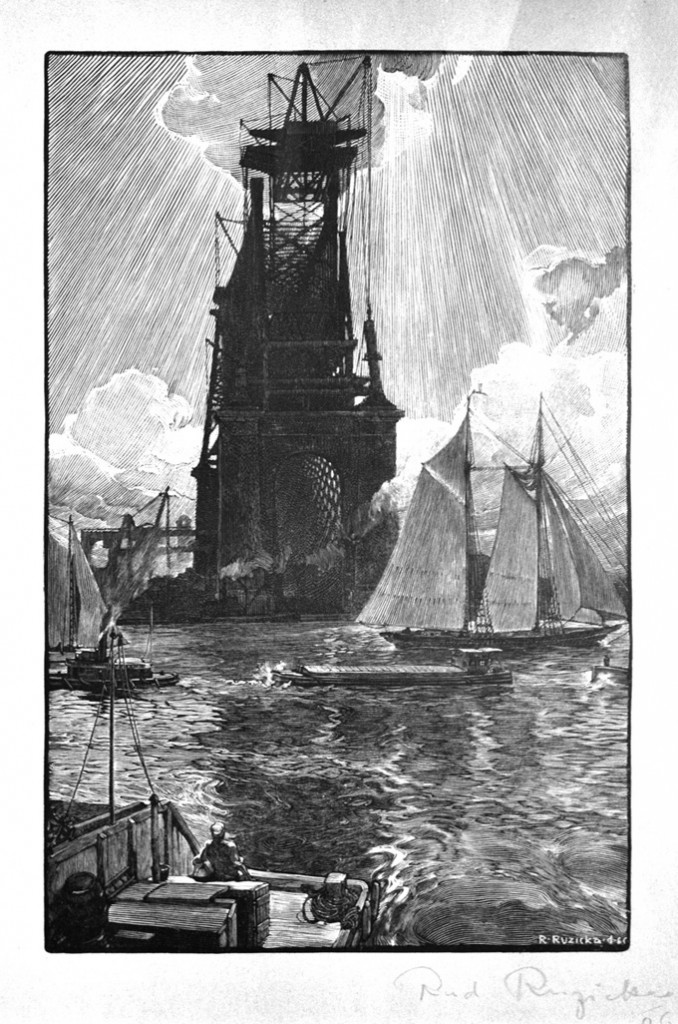

(Bridge construction, New York harbor), Rudolph Ruzicka (Czech-born American, 1883-1978), 1906, 7 1/2″ x 4 7/8″ (my collection)

And here’s the Rudolph Ruzicka bridge print from 1906. (Perhaps this is the Queensboro Bridge completed in 1909.) Do you know where he was trained? Does this piece differ in technique from that of Kingsley-Wolf-Cole heyday?

Ruzicka, who came to the U.S. at ten years of age, trained at the Chicago Art Institute, the Art Students League of New York and the New York School of Art. This piece (and the eight restrikes of his work that I have) all appear to have been done in the style of the Old School. On the other hand we should keep in mind that Ruzicka had to make a separate block for each color, i.e. three blocks for each image.

What discoveries did you make in the process of writing your book?

• Century Magazine sent Timothy Cole to Europe for “one year” in 1883 to make interpretations of the great art that was there. As things worked out he didn’t return to the U.S. until 1910, twenty seven years later. Four large books resulted.

•The Eiffel Tower can be thought of as signaling the emergence of the art of the American wood engravers. It was erected as a symbol of the International Exposition of 1889 in Paris which was the event at which members of the Society of American Wood Engravers received gold, silver, and bronze medals and international recognition and were subsequently designated best in the world.

• Electrotyping: enabled printing from precise copper replicas of wood engravings and thus made possible safe storage of the blocks and sharing of the images. This process came into general use at about the time of the Civil War.

• Making ready: The process of gluing paper thicknesses to the press to make pressure greater in one place than another. (darker areas of a print require greater pressure)

• The New School vs the Old School – Members of the Society of American Wood Engravers broke tradition to the advantage of art.

• Kingsley’s “car”: Elbridge Kingsley’s brother built him a horse-drawn wagon that was enclosed and could be lived in on location. Kingsley loved the outdoors and used it a great deal. He often invited his fellow engravers and his family to share it from time to time. It was clearly an RV ahead of its time.

•Japanese tissue for proofs: Kingsley and his fellow engravers found that wood engravings produced the best images when they were printed manually on tissue imported from Japan which became available during the development of the Society.

• The moiré effect: some of our initial efforts to copy wood engravings were frustrated by the appearance of an unexpected and unwanted washboard effect. Modern scanning procedures cause this unless a stochastic screen is used rather than the usual screen that produces dots in orderly rows. The book very nearly could not be illustrated until a way was found to avoid the moiré effect.

• Kingsley originals: I found two main repositories, The Forbes Library of Northampton, MA, and the Art Museum of Mt. Holyoke College of South Hadley, MA.

Many thanks to Bill Brandt for taking the time to respond to my, perhaps too many questions. While investigating the web for this post, I came across several very useful sites:

• A page-turning copy of the 1901 Catalogue of The Works by Elbridge Kingsley, Mt. Holyoke College: http://archive.org/stream/catalogueofworks00moun#page/n7/mode/2up

• The William James Linton Archives at: http://www.meltonpriorinstitut.org/pages/linton.php5/page_29/page_30.html

• A page-turning copy of The Life and Works of Alexander Anderson M.D.: the First American Wood Engraver: http://archive.org/stream/lifeworksofalexa00burrrich#page/n9/mode/2up

• An online version of A History of Wood Engraving by George E. Woodberry, 1883: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/40638/40638-h/40638-h.htm

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/interpretive-wood-engraving-interview-with-its-author/trackback/

Pingback: 2018 Annual Summer Conference - Wood Engravers Network