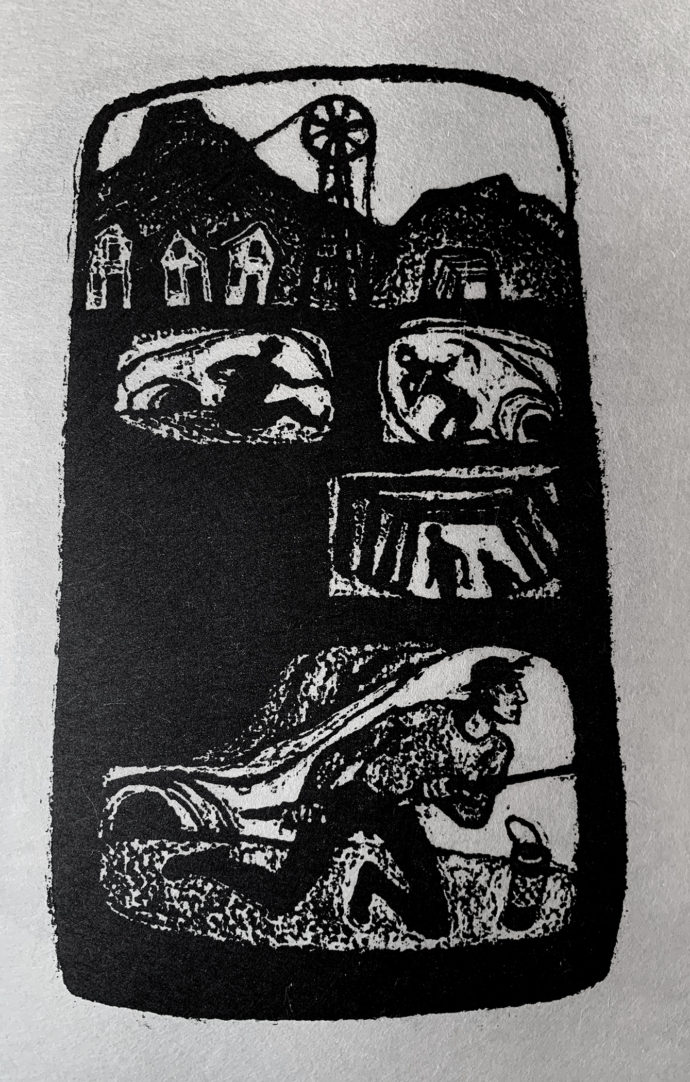

Harry Gottlieb’s “Coal Pickers’

Discovery

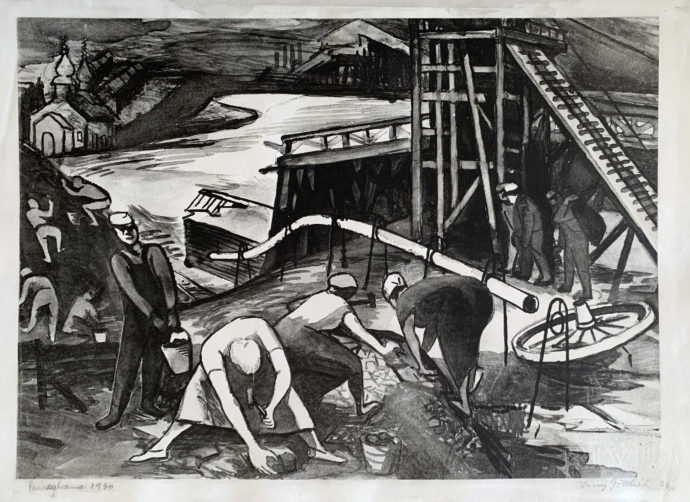

The object of this blog post is about the coal culture in the United States during the Depression and how artists depicted coal culture in printmaking. The catalyst for that discussion was my recent purchase of Harry Gottlieb’s lithograph The Coal Pickers. However, when I went online to check out the size of this image so I could write the caption above, I made a discovery that was disturbing at first. Fortunately, that concern diminished when I checked one reference book.

The image in my copy measures 10″ x 13 3/4″ while the copy on William P. Carl Fine Arts website is listed as 12″ x 15 7/8″. The Princeton University Art Museum also has a copy with that measurement. Comparing my copy with the one on the left, one soon realizes that my copy has been trimmed on the left, top and a little bit on the right.

Is my copy somehow to original or was altered after the printing? First I compared signatures and there’s nothing suspicious with the one on my copy. Then I consulted the book America Today: A Book of 100 Prints (Equinox Cooperative Press, News York, 1936) because I knew Gottlieb’s print was illustrated in it. This book was essentially an exhibition catalog for the American Artists’ Congress, which organized, according to its introduction, “a nation-wide exhibition of duplicate exhibits to be held simultaneously in thirty American cities during the month of December, 1936.” To my relief, the image of The Coal Pickers in the book America Today matches my copy.

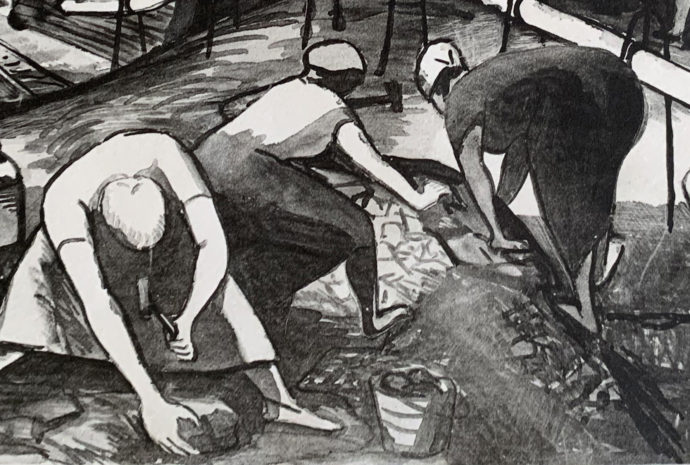

Gottlieb drew his image on a lithographic stone using liquid tusche, which is kind of a greasy ink that can be applied with a pen or a brush or even dabbed on. It can be diluted in order to create a wide variety of grays. Comparing the larger and smaller versions of Gottlieb’s print, it appears that there are no differences except for the cropping. Even in the areas along the bottom of the images where there seems to be areas of burnishing (lightening) match.

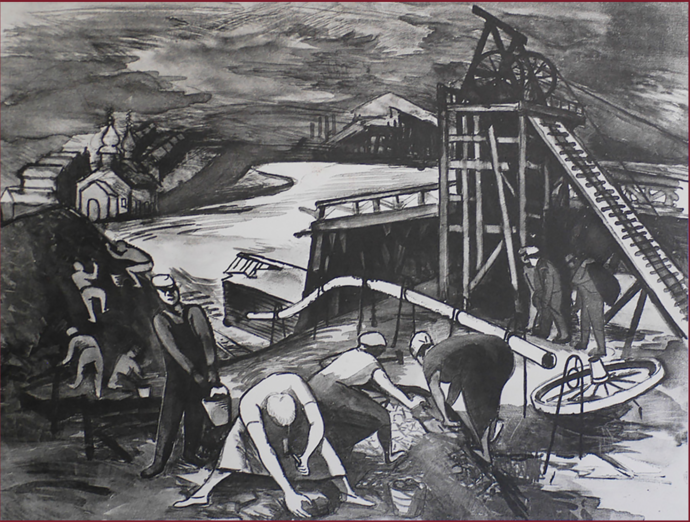

I superimposed the second, smaller edition of “The Coal Pickers” on top of the first, larger edition. I lightened the latter so the differences between the two can easily be seen.

So this is my assumption: The larger image came first, and Gottlieb pulled an edition. Then he decided he could focus on the coal picking activities that are visible on the lower half of the image by making his trims by masking off the unwanted areas or desensitizing the stone in these areas. The major loss was the wheeled mechanism on the top of the small tower on the upper right. It’s highly unlikely that Gottlieb started with the smaller image and then added to it later. Doing that would definitely have left a shadow where the original margins were and the tuche marks would be discontinuous.

Seeking a better explanation of how Gottlieb might have trimmed his lithograph, I asked Justin Sanz, Workshop Manager/Master Printer at EFA Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop in New York. (The workshop is a program of The Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts.) He emailed me his response:

“It would be hard for me to give you a definitive answer without seeing the print in person, but I can tell you how it was most likely done. The cropped composition would either be masked out by laying newsprint strips (or a newsprint frame) on the edges of the stone for every print, or erasing the outer edges of the drawing with a strong etch and Snake Slip stone. Either of these methods could achieve the same result, but it is quite labor intensive to erase the drawing, and difficult the achieve a sharp image edge. If this cropped composition were only printed this way for a couple of proofs or (small edition) and has sharp image edges, chances are it would be the newsprint method.”

I found two other copies of the smaller version of The Coal Pickers for sale online. One is offered by the Elizabeth Moss Galleries (Link); another by the Sragow Gallery (Link) Besides the size both share another attribute of my copy. On the lower right of my copy one can see the watermark “RIVES,” while on the Moss copy one can see “FRA…” in the same font, and on the lower right of the Sragow copy one can see an uppercase backwards “K,” again in the same font. RIVES BFK is manufactured by the Arches Mill in France. Bill Carl checked his copy of the larger version and reported not finding a watermark.

In short the large print is from the first edition and the trimmed edition represents the second edition. I assume the first edition was small, while the second edition would have been at least 30 if it had appeared in all 30 American Artists’ Congress venues in 1936.

My copy is titled “Pennsylvania 1930,” but the pencil used is different from that used for the signature. So I assume it was added later. Nor does the 1930 date jive with the history of Gottlieb’s ventures into coal country (to be discussed later).

Coal Picking

A quick check online shows that the term “coal picking” originated in England in the mid 19th century. But turning to the Great Depression in America, I found this on explorepahistory.com:

“Bootleg coal mining began with people picking culm [waste] piles during the strikes of 1902. Women and children collected this coal to heat their homes. During the Great Depression, however, huge layoffs precipitated a larger bootleg movement. Most unemployed miners, especially in rural areas of Pennsylvania, had no way to earn enough money to survive so ‘we just dug our own holes,’ as one bootleg practitioner recalled. What started out as small mines worked by three or four men in the night under extremely dangerous working conditions, eventually grew into more organized operations worked in broad daylight with unions to protect them from law enforcement. By the 1930s it is estimated that bootlegging coal had become a thirty-million-dollar industry which cost the Commonwealth millions in uncollected taxes.”

It seemed appropriate to use this quote because the source of Gottlieb’s imagery was the anthracite coal district in eastern Pennsylvania. And here’s another quote on coal picking. It was posted on the site coalpail.com (link):

“Ever since anyone in the Pennsylvania anthracite field can remember, it has been customary for miners and their families to go with sacks or pails to the culm dumps surrounding their bleak towns and pick coal from among the rock and slate thrown out in the breaking and cleaning processes at the big collieries. The pickers usually were the poorer families. Most of the companies permitted this, and the ‘pickings,’ as a rule, were used for fuel in miners’ homes. Occasionally some miner paid his church dues or a small grocery bill with a few bags of coal he had picked up on the dumps. No one ever sold it for cash.”

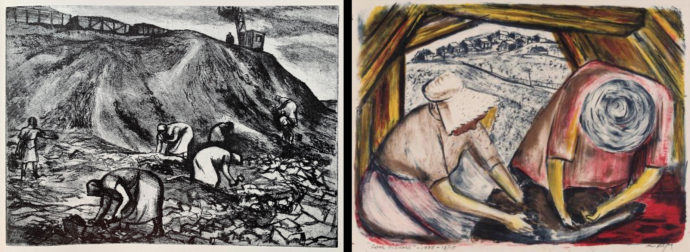

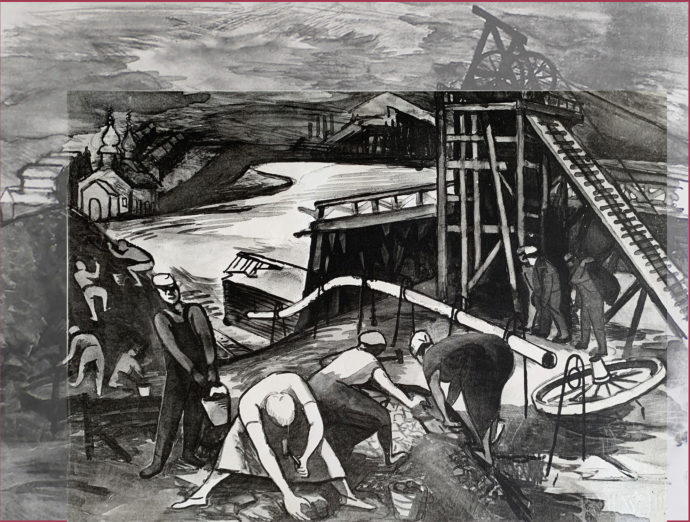

Above are two other portrayals of coal picking. Both Margaret Lowengrund and Riva Helfond worked in the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project in New York in 1936. The Lowengrund print was also in the American Artists’ Congress exhibition.

Harry Gottlieb

Romanian-born (1895) Harry Gottlieb emigrated to American with his Jewish family in 1907 and settled in Minneapolis. He studied at the Minneapolis Institute of Art from 1915-17, then at the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts, and by 1918 arrived in New York and attended the National Academy of Design. In 1935 he joined the Federal Art Project in New York and was one of the first members of the project’s screen printing unit. In her book Radical Art: Printmaking and the Left in 1930s New York (University of California Press, Berkeley, 2004), Helen Langa wrote:

“Harry Gottlieb, who was also affiliated with the Communist Party (although he never openly acknowledged this), focused many of his prints on industrial workers, labor organizing, and the toll of unemployment; his labor themes celebrated the diverse experiences of steelworkers, coal miners, road repair crews, student beauticians, and fishermen. Gottlieb used a simplified style of realist drawing to create rounded, slightly caricatured figures, usually male and usually portrayed in outdoor settings.

In her section “Mining Themes: Local Information, Varied Opportunities,” Langa wrote:

“Harry Gottlieb and Elizabeth Olds became interested in mining subjects soon after they started working at the Graphic Arts Division–perhaps after they viewed an October 1935 ‘March of Time’ newsreel with a segment on striking coal miners in Pennsylvania. When these men were forced from their jobs by plant owners unwilling to negotiate new union contracts, they began a bootleg operation to dig coal from surface seams and sell it at low prices. In the spring on 1936, Olds and Gottlieb drove over to Pennsylvania to see this bootleg system for themselves. The miners, unwilling to trust their unexpected visitors, insisted that the two artists drive to a nearby town and join their union before making any sketches. Gottlieb and Olds complied with this demand and later exhibited paintings, drawings, and prints based on their studies.”

Next, I’ll present works by two other artists who traveled to the anthracite mining region of eastern Pennsylvania: Harry Sternberg and Riva Helfond. Both joined the New York FAP atelier, and coincidentally, I have relevant prints by them in my collection.

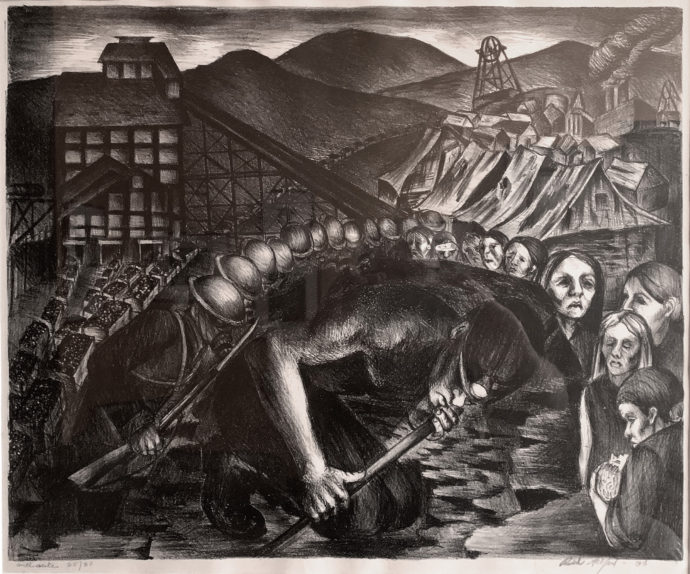

Riva Helfond (1910-2002), “Anthracite,” 1936, lithograph, ed. 30, 15″ x 18 3/4″ (Please excuse the glass reflections.)

Riva Helfond

Riva Helfond was born in Brooklyn into a family of Russian Jewish emigrés. According to Elizabeth Seaton’s book Paths to the Press: Printmaking and American Women Artists, 1910-1960 (Marianna Kistler Beach Museum of Art, Kansas State University, 2006), “the family’s low income influenced her left-leaning politics as a young adult. Helfond pursued her art education in New York at the School of Industrial Arts and the Art Students League during the late 1930s…. At the League Helfond studied printmaking with the young Harry Sternberg…. In 1935 Russell Limbach invited her to join the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project as lithography instructor at the Harlem [Community Art] Center, where she taught until 1938…. Between 1936 and 1941 Helfond also worked as an artist in the New York WPA-FAP printmaking workshop.”

Like Gottlieb, Helfond was an early practitioner of screen printing. Seaton wrote: “Helfond also joined artists such was Elizabeth Olds and Ruth Chaney on the [WPA-FAP] division’s screenprinting project overseen by Anthony Velonis. Helfond was among the first women to exhibit with the Silk Screen Group, which formed in the late 1930s to promote the medium in the private market.”

Her marriage to sculptor Bill Barrett proved providential for both her and her WPA colleagues’ efforts in Pennsylvania coal country. Seaton wrote:

“During the summer of 1936, Helfond, Blanche Grambs, and other students from the Art Students League accompanied Harry Sternberg on a trip to the anthracite coal mines of Eastern Pennsylvania…. Barrett’s roots in the region helped artist gain access to the miners. He had worked in the Lansford mines after school as a boy and his Welsh family still lived in the area…. As a woman Helfond was allowed mainly to observe life outside the mines, but she and other female artists did gain access to the interior of a ‘model mine.’ ”

Helen Langa also mentioned the “model mine.” She wrote: “Some artists, unable to enter the mines, took advantage of an unexpected discovery. For tourists, Lansford industrialists had created a ‘model mine’ where visitors were given protective clothing and guided through the same types of shafts and tunnels in which miners worked. This model was probably intended to persuade outsiders of the safety of mining operations and to put industrial labor in the best possible light, but it also made possible convincing portrayals of miners on the job.”

In her print Anthracite, Helfond not only portrayed a miner at work but created a collage that in one image depicted the woes of the miners and their families. Here a miner is bent not only by a cramped workspace but by armed militias (national guardsman?) to the left and the worries of families to the right.

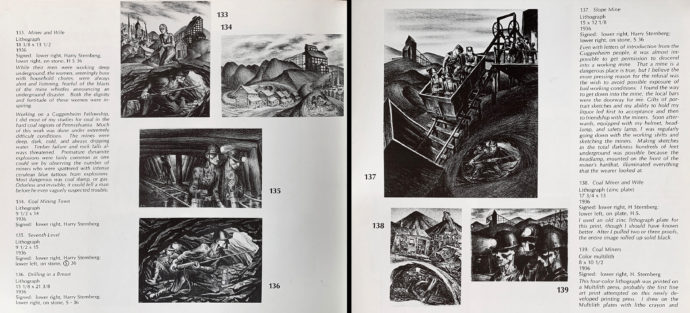

Facing pages in “Harry Sternberg: A Catalog Raisonné of his Graphic Work” (James C. Moore, Edwin A. Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita State University, Kansas, 1975)

Harry Sternberg

Born in New York, Harry Sternberg (1904-2001) was the son of Hungarian and Russian Jews. His parents lived with eight children in a tenement in the Lower East Side. The family moved to Brooklyn in 1910. At age nine he began art classes at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. His art training continued at the Art Students League between 1922 and 1926. In her book No Sun without Shadow: The Art of Harry Sternberg (Museum, California Center for the Arts, Escondido, 2000), Ellen Fleurov wrote: “In the fall of 1933, Harry Sternberg began to teach at the Art Students League of New York… A student himself at the League only five years earlier, Sternberg, at the age of 29, was now the youngest faculty member in the that school’s venerable history…. Sternberg remained with the League for nearly 33 years until his retirement in 1966.”

In her book Radical Art Langa wrote: “Sternberg made several trips to Lansford after he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1936 for a project focusing on industrial subjects. When he discovered that mine owners would not let artists go down into working mines, he persuaded men he met in a local bar to sneak him in on their shift so he could gain firsthand experience on the job.”

Harry Sternberg, #24, woodcut with Dremel, in his autobiography “A Life in Woodcuts” (Brighton Press, San Diego, CA, 2001), 8 1/2″ x 5 1/4″. For this image Sternberg turned to some of his coal mining prints he made in 1936 (as illustrated in the catalog raisonné pages, above).

In No Sun without Shadow appears an essay–”Coal Town”–that Sternberg wrote ahead of a 1937 exhibition of his coal and steel prints at Frederick Keppel and Company in New York. He began by saying on arriving in Lansford: “The grey culm banks, the skeleton mine tipples, and the crazy wooden shacks were full of rich ‘form’ for picture making…. I was so excited by the richness of the surface material, that only after I had lived with the miners for weeks did I begin to really see and draw a mining town.” He then described the consequences of life in a coal mining town:

“The miners, their wives, and kids were fine romantic stuff to draw. Faces with strange deep blue marks pitted in the skin, men with fingers missing, with stumps of arms and legs, women with gaunt tired faces, then barefooted children in overalls. Grand stuff to draw and paint.

“But then I realized that bare feet and patched overalls meant no money for decent clothes. The interesting lines in the women’s faces were worn with patient stoical waiting for their men to come home from the pits. Something more had to be got in the deep-socketed eyes, the sunken cheeks, the lips drawn back from the teeth, when short gasping breath tells of miners’ asthma, the dread silicosis caused by coal dust in the lungs.”

He then wrote at length to detail the dangers of working the coal seams, but I’ll leave it at this one sentence of Harry’s: “Mining is dangerous, filthy, rotten work.”

In 1936 he served on the selection panel for the “American Today” exhibition by the American Artists’ Congress. His print Coal mining Town (No. 134 in the left-hand page above) was chosen for that exhibition.

James Allen

For a 1984 exhibition of prints by James E. Allen, the Mary Ryan Gallery in New York published a small catalog with a brief essay by Elisa M. Rothstein. She wrote: “Born in Louisiana, Missouri, in 1894, James E. Allen was raised in Montana. He left home in 1911 to study painting and drawing at the Art Institute of Chicago. Soon after, he headed for New York where he took classes at the Art Students League, the Grand Central School of Art, and the Hans Hoffman School…. With the advent of World War I, Allen had already established himself an as illustrator, working as a staff artist for Doubleday-Page Publishing Company. From his studio on 23rd street in New York, Allen produced illustrations for publications such as Colliers and the Saturday Evening Post.” His work as an illustrator can be found on the pulpartists.com website. (Link)

“In 1925,” Rothstein wrote, “he moved to Paris where he met Howard Cook. The two artists shared a studio and began experimenting with a variety of printmaking techniques.” Howard Cook, according to Betty and Douglas Duffy in their 1984 book The Graphic Work of Howard Cook: “The artist himself printed all of his graphic work with the exception of his lithographs.” I mention that because Mary Ryan in the acknowledgments to her publication on Allen wrote: “Allen did not print his own work, but there are no extant records, to my knowledge, which document who did.”

In Rothstein’s essay on Allen, she wrote: “During the Depression years Allen, now back in New York, worked consistently in the field of commercial art. His etchings and lithographs began to receive widespread academic and critical acclaim.” The print that drew attention in 1932 was The Builders of men connecting girders for a New York skyscraper. His prints–whether of workers in steel foundries, oil refineries, or laying huge pipes–focused on their nobility and their work. Also in the Ryan Gallery catalog is a brief essay “James E. Allen, an Appreciation” by David W. Kiehl, in which he wrote: “There is consistent power in these prints from the 1930’s and 40’s; their heroism lies in the muscular robustness of form and subject–of the derring-do of a “Spider Boy” riding the ball of a crane, or of “Builders” taking a break on a beam high above the city. Allen valued hard work and personal ingenuity for survival, and his prints reiterate this personal creed.”

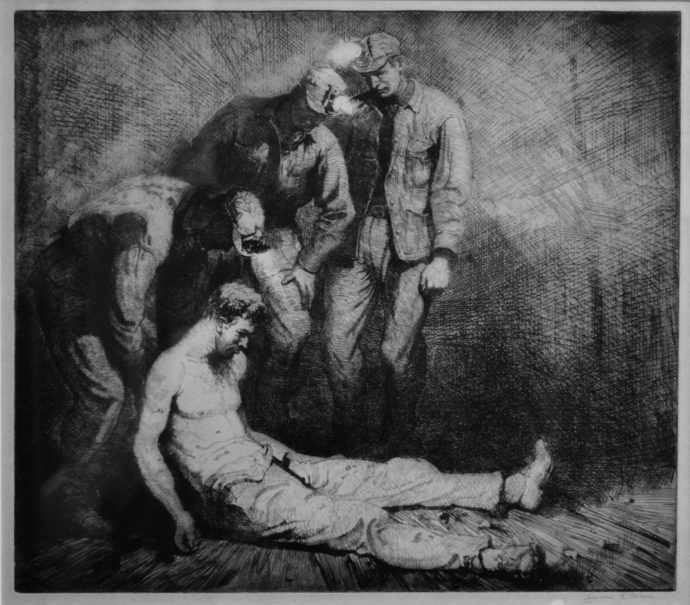

His etching The Accident concludes my survey of mining art in my collection. It’s a very tender print, a pieta if you will. It’s quite different for Allen’s other worker images. None of the grime and struggle of Sternberg’s or Gottlieb’s or Olds’ or Helfond’s or Lowengrund’s prints are apparent. And no writer in the Ryan Gallery catalog mentions the print. So I don’t know the circumstances about its creation. The catalog does state that while the acclaimed print The Builders was published an edition of 100, only 10 copies of The Accident was made.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/harry-gottliebs-coal-pickers/trackback/