Harry & Bill: Making of a woodcut autobiography

Precede

This article was first published in the spring 2017 issue of On Paper: Journal of the Washington Print Club. Because the blog format is not handcuffed by the restrictions of page layout and color usage, this post provides an ideal opportunity to republish my article.

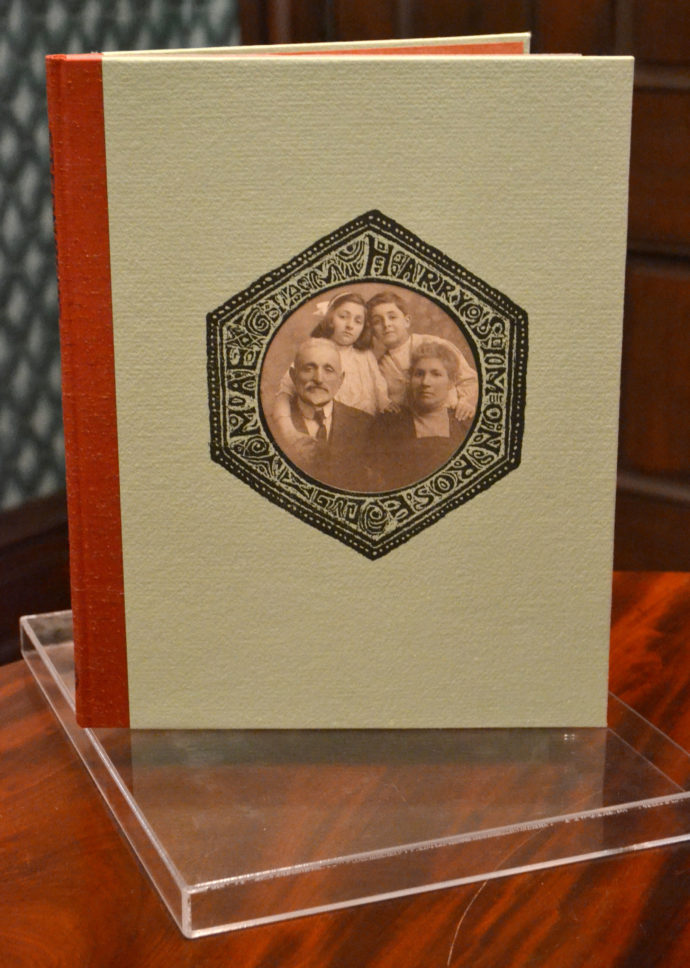

Sternberg: A Life in Woodcuts with its original lucite slipcase. (Photo by Scott Ponemone. Courtesy of the Estate of Harry Sternberg.)

INTRODUCTION

Fortune smiled on me last winter when I was able to purchase at auction a copy of Harry Sternberg’s book Sternberg: A Life in Woodcuts. I hadn’t come across a copy of his autobiography since soon after it was published in 1991 by Brighton Press, San Diego, California. At the time I couldn’t afford it. However, as a lover of books featuring original relief prints without text—precursors of today’s graphic novels—I never forgot about it. Since his book was published in two small editions of 40 each—a regular edition and a deluxe one—I never had a second chance to own a copy until December 2016.

So now I had signed copy number XL/XL. Did I have the deluxe or the regular edition? To my delight, a quick online check for Brighton Press confirmed that this small press was still publishing and, more importantly, Bill Kelly, who founded the press in 1977, was still actively involved. (See the Brighton Press website at http://www.ebrightonarts.com/)I emailed Kelly to see if he would he be willing to discuss the making of A Life in Woodcuts and his experiences working with Harry Sternberg, who was in his eighties when the project began. I especially wanted to ask Kelly how Sternberg cut his blocks. The marks that made up his woodcut images were so irregular, I didn’t get a sense of what tools he was using.

But first, who was Harry Sternberg (1904-2001)? Born in the Lower East Side of Manhattan to Jewish emigrés from Eastern Europe, Sternberg studied at the Art Students League. He learned etching from Harry Wickey and taught at the Art Students League for 35 years. In 1927, when Sternberg was 23, one of his prints was exhibited by the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and the American Marxist magazine New Masses illustrated one of his drawings. Over the next five years, his works appeared in numerous group shows, including at the newly opened Whitney Museum of American Art. Carl Zigrosser of the Weyhe Gallery in New York gave him his first one-person show in 1932. (Ellen Fleurov, No Sun without Shadow: The Art of Harry Sternberg. San Diego: California Center for the Arts, Escondido 2000, 11.)

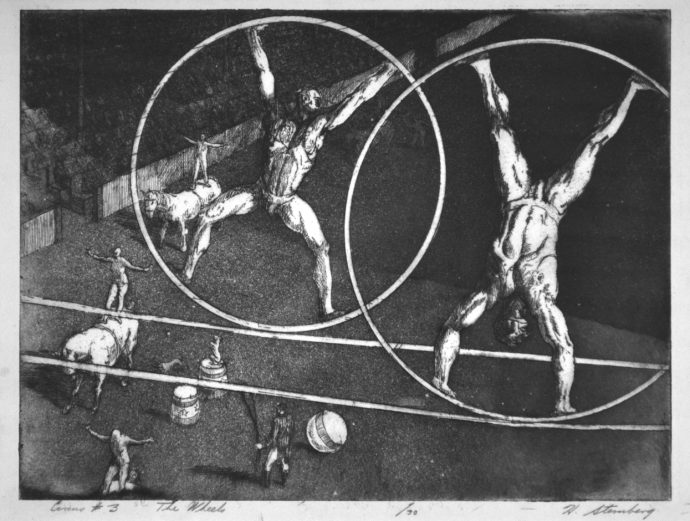

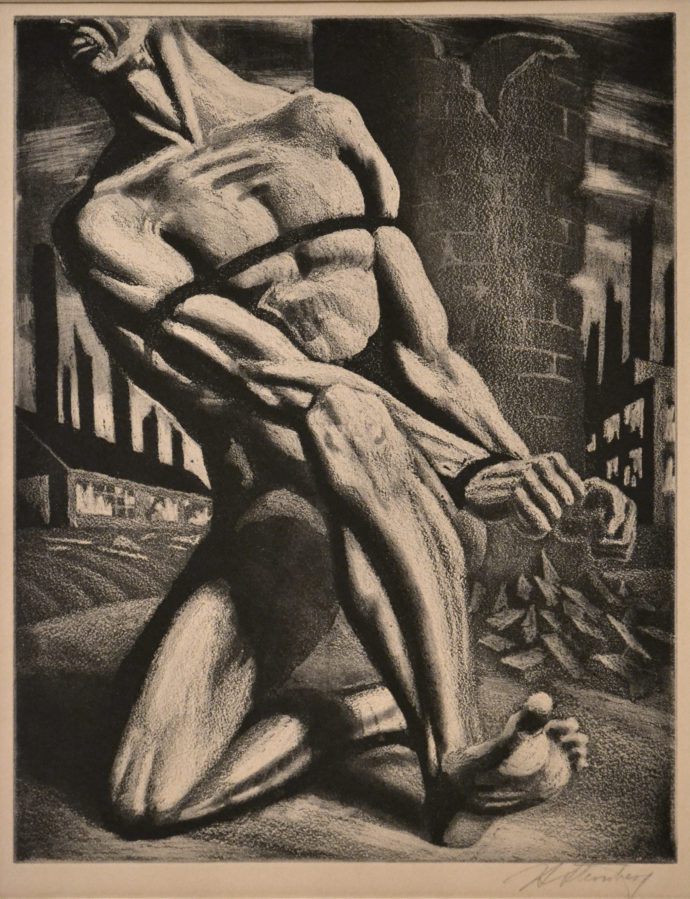

For collectors like myself, when I think of Harry Sternberg, I think of his pre-1950 prints that pulsed with images of New York street life, the hardships of the working man, his fascination with the circus, and even his imagining humans flying through the air to represent musical instruments. His art often reflected the leftist political views common among artists of the day.

Harry Sternberg, Circus #3: The Wheels, etching and aquatint, 8 7/8″ x 11 7/8″, 1929 (March), 1/30, signed. Of his circus images, Sternberg recalled, “I had never been to a circus when I worked on this series of plates. I invented my own circus as a means of exercising my interest in the human figure in motion through space.” (James C. Moore. Harry Sternberg: A Catalogue Raisonné of His Graphic Work. Wichita: Edwin A. Ulrich Museum of Art, 1975, 40. Print #38) (Photo by Scott Ponemone. Courtesy of the Estate of Harry Sternberg.)

Harry Sternberg, Bound Man (Enough), crayon aquatint, 14 7/8″ x 11 3/4″, 1947, signed. (Photo by Scott Ponemone. Courtesy of the Estate of Harry Sternberg.)

Sternberg had a working career of over seven decades. After World War II his prints mostly drifted away from his earlier themes of social consciousness. This was especially true after he left New York in 1966 for Escondido, north of San Diego. From Ellen Fleurov’s book No Sun without Shadow, pg. 118: “Suffering from lung disease, he is advised by his doctor to leave New York. Takes extended leave from teaching…. Intends to stay for only one year, but settles permanently in California and retires from [Art Students] League.”

HARRY & BILL

Had Sternberg not settled in southern California, he wouldn’t have met Bill Kelly and there wouldn’t have been A Life in Woodcuts. Kelly recalls:

I was the only professional printer for artists in San Diego and I was doing some print publishing as well, primarily for Mexican artists. This was in the early 80’s, and I was running the San Diego Print Club with several other artists at the time. Harry made an appointment, brought in three plates to test me on. I knew his work from an earlier show and several books and print publications I was aware of. I owned Carl Zigrosser’s book [Artist in America: Twenty-Four Close-ups of Contemporary Printmakers. New York: Knopf, 1942] which had a focus on Harry.

(All quotes from Bill Kelly were obtained via email exchange between Kelly and myself in January and February, 2017.)

Kelly was taken with Sternberg’s printmaking.

He knew how to make a print, and his compositions were emotive, expressive and, I would say, very sophisticated. He knew how to draw the figure and early on impressed me with a drawing he did of his mother on her death bed. It was her hands I remember the most. As I began to really know his work and saw his studies, it became clear that he had a great affinity for the exaggerated body. He apparently liked my first printings, and I worked regularly printing editions for him for the next 15 or 20 years.

The next step in their collaboration actually began when Kelly’s Brighton Press published a book in 1985: A Colored Poem presented poems by W.D. Snodgrass illustrated with colored etchings by DeLoss McGraw. Kelly said, “The book did well. It sold to collections. One dream I had was to know writers, and this was a perfect vehicle for that. Still is.”

Kelly’s new endeavor intrigued Sternberg, and Sternberg had some definitive views on the enterprise. Kelly remembers:

He [Sternberg] was slightly mystified by this poetry thing. One day when he came in to print and knew our financial troubles, he said he had figured out why we weren’t making much money. He declared the poetry was limiting our sales and undercutting the value of the prints. The binding was expensive, and museums didn’t really quite know what to do with them. Still books made sense to us, and Harry stayed amused.

After five books or so I decided to approach Harry with a book idea. A book of hands, powerful and expressive hands. He wasn’t interested. He proposed a book with a poet, not a living poet but a poet none the less.… I wanted to work with living breathing poets, but nothing was lining up.

You can see our mission at the time was twofold: the artist makes the work and we put the work to the service of an idea in book form. There really wasn’t much more to it than that. It led us into some fascinating projects. We have rarely deviated from this view and are just finishing our 50th book. Writing though was important to us and has remained our way into the making of images and text. Harry was different. He was a good reader…but his work was purely visual.

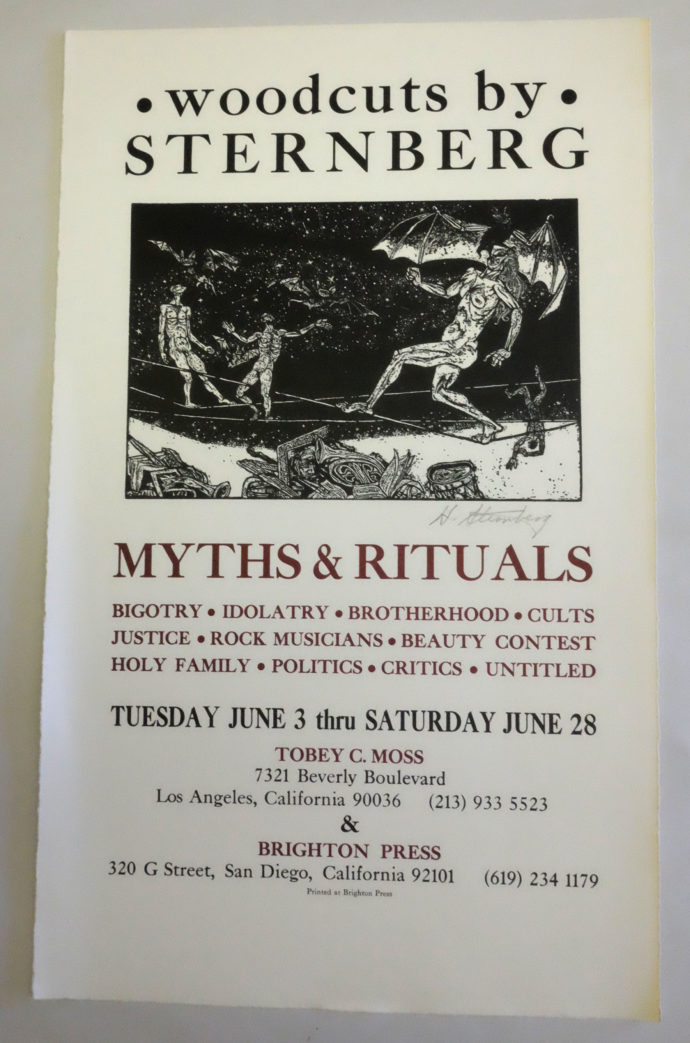

The first Brighton Press imprint of Sternberg’s prints was Myths and Rituals, a suite of eleven large woodcuts in an edition of 30, 1986. The prints were so large that Kelly decided to issue them not enclosed in a portfolio, although Kelly had designed one. For instance, Sternberg’s woodcut Creators and Critics measured 34 5/8” x 17 7/8”. (Images from Harry Sternberg’s Myths and Rituals can be found on the San Diego Museum of Art website. They are numbered 2000.55.1 through 2000.55.11. “Sternberg, Harry.” San Diego Museum of Art, accessed March 10, 2017, http://www.sdmart.org/collections/artists/1.

“There are some strong images in this series and some lovely puns,” Kelly said.

I think he was just enjoying the making. We weren’t so much—the printing of these with a spoon, especially when the fragile paper ripped after 45 minutes of printing. There were three, then four of us printing hard….Myths & Rituals never made it to book status. We tried a version in polymer but didn’t like the scaled down feel of it. There were 11 prints, all large….We sold several, all 11 as a suite of prints on the theme as Harry developed them. When he signed the prints, he would often change the name. He would do this right in front of our eyes. It drove us crazy. He just laughed it off. He also would change the edition number.

A poster for an exhibition of Harry Sternberg’s suite of woodcuts Myths a& Rituals. (Image provided by Bill Kelly. Courtesy of the Estate of Harry Sternberg.)

An exhibition of this series was held in June, 1986, both at Brighton Press in San Diego and at the Tobey C. Moss Gallery in Los Angeles.

In 1989 Kelly hit upon an idea for a book to excite Sternberg: an autobiography in woodcuts.

We were doing a lot of woodcuts with Harry, and they were good. I drove the 30 miles to Escondido, where Harry’s studio was. He heard me out and loved the idea. I came back elated, and within a short time he was doing a block nearly every week…. He felt the book. I can imagine—he was 89—that, when he said the images flooded out from his memory, he was feeling the joy of an artist living his life in the arts.

Among the first decisions about the production of A Life in Woodcuts was how was it to be presented. Sternberg, the veteran printmaker, gravitated toward a portfolio of loose prints. Kelly, however, thought in terms of bound books. They reached a compromise: two editions of 40. One edition numbered in Roman numerals would be just the book containing Sternberg’s woodcuts printed from the block; the other edition in Arabic numerals would be the same book (but using different papers) plus a portfolio of loose prints, the same prints that appeared in the book. Each was signed by the artist. (Kelly said Sternberg chose to number the portfolio edition in Arabic numerals because “he thought it would be harder, maybe weird, to sign prints with Roman numerals.”)

Another critical decision was the size of the book and, therefore, the prints.

The book needed to be big enough to give Harry freedom of movement. His hands shook until the Dremel hit the wood. Then he was amazingly steady. He like the scale but was concerned with restrictions as to composition. He couldn’t change page size but could do whatever he wanted on that page. He asked if he could break the square [an image with all right angles], and we cheerfully said yes.

Photos of Harry Sternberg using a Dermel to create woodcuts for Sternberg: A Life in Woodcuts. (The images appeared in Ellen Fluerov’s No Sun Without Shadows, pg. 121. The photo credits list Thomas B. Szalay as photographer. I contacted him but he couldn’t confirm that the photos were his.

Kelly’s mention of “Dremel” helps explain how Sternberg cut his woodblocks. The name refers to a rotary power tool with interchangeable bits. It was developed by Albert J. Dremel, who founded the American Dremel Company in 1932. It appears that Sternberg first used the power tool in creating The Atom, an intaglio print from 1950. Of that experience, Sternberg wrote, “Instead of acid or engraving tools, I used a power drill for cutting most of this plate. I worked with a flexible shaft drill, not unlike those the dentists use, with various bits or point.” (Moore, Harry Sternberg, print #196)

In Sternberg’s instructional booklet Woodcut, he wrote:

The use of powered cutting tools in woodcut is relatively new. The tool itself is similar to that used by dentists, but is smaller and more compact. It consists of a flexible shaft attached to a motor. At the end of the shaft is a grip into which cutting burrs and grinding wheels can be fitted interchangeably. A foot-controlled rheostat that starts, stops, and varies the speed of the motor, is desirable. The rapidly revolving burrs do the cutting, so that the hand is used solely to guide the tool. By using several burrs and varying the speed of revolution, a wide variety of textures and lines may be obtained on the face of the wood block. (Harry Sternberg, “The Power Drill” from Woodcut. New York: Pitman Publishing Corporation, 1962.)

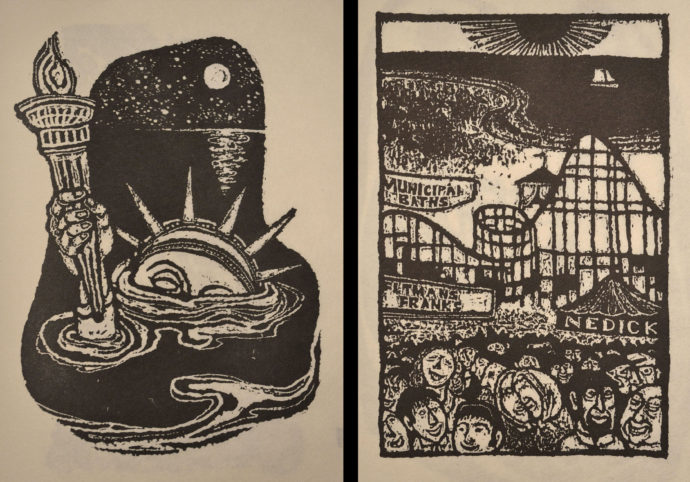

Plates #3 (left) and #15 from Sternberg: A life in Woodcuts. (Photos by Scott Ponemone. Courtesy of the Estate of Harry Sternberg.)

Sternberg’s use of the Dremel explains why the prints in A Life in Woodcuts lack the marks made by traditional woodcut tools, namely chisels, gouges, and knives. Instead, his woodcuts have an erose, almost pitted surface, which gives them an edgy, nervous energy.

Sternberg’s project progressed. Kelly recalls:

Preliminary drawing and completed woodcut for image #31 in A Life in woodcuts. (Drawing courtesy of Bill Kelly. Photo (right) by Scott Ponemone. Courtesy of the Estate of Harry Sternberg.)

Preliminary drawing and completed woodcut for image #8 in A Life in woodcuts. (Drawing courtesy of Bill Kelly. Photo (right) by Scott Ponemone. Courtesy of the Estate of Harry Sternberg.)

He was steady. Almost every two weeks or certainly once a month he would show up with a new block or two. Sometimes he showed us drawings but not always. He was excited by his memories and loved having printers who would drink with him. I don’t believe there were blocks or prints that didn’t make the cut. Some were better than others, but we just watched printed and counted. No target number was set, just waited for him to tell his tale.

One notable feature is that each print in the book was numbered to correspond with a biographical chronology at the end of the book. That idea came about when art editor Helen Faye interviewed Sternberg. According to Kelly, “[she] came up with the chrono dating and numbers. Seemed like quite a good idea now that I think back, and I am certain Helen thought of this. There are some inaccuracies in the chronology, caught by Malcolm Warner in his book. Harry was cagey and often inventive, but for the most part he was sharp and accurate as far as we can tell.”

(Malcolm Warner, The Prints of Harry Sternberg. San Diego: San Diego Museum of Art, 1994. At the time, Helen Faye was director of art editing in New York and San Diego for Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Bill Kelly said: “When she retired, she came to work [for us] as the Corrector of the Press. She is 96 now.”)

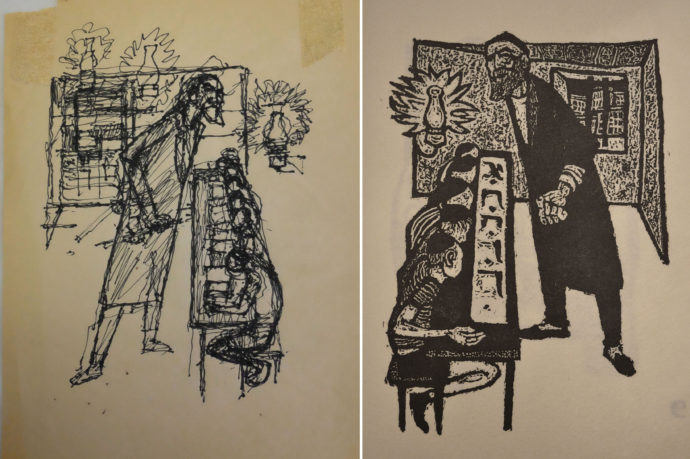

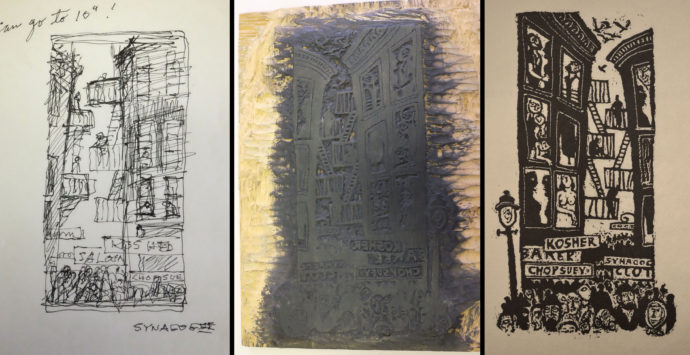

Preliminary drawing, the completed woodblock and the completed woodcut for image #4 in A Life in woodcuts. (Drawing and woodblock courtesy of Bill Kelly. Photo (right) by Scott Ponemone. Courtesy of the Estate of Harry Sternberg.)

Kelly used a Vandercook 219 press to print the project: “Blocks were raised to type high and lead type for the chronology. The portfolio prints were printed by spoon. I still like to print that way.”

(Top) Sternberg family photograph: father Simon, sister Mae, Harry and mother Rose. (Bottom) The photo as prepared to run on the cover of A Life in Woodcuts. (Courtesy of Bill Kelly)

The cover features a round photograph of the Sternberg family: Harry at age eight, his sister Mae, and his parents Rose and Simon. Harry surrounded the photograph with a hexagonal frame comprising the family names. Suspecting that there was a story behind that design, I asked Kelly about it:

The cover was one of the last things, and it was a little hard to resolve. (I found the photo Harry gave us of the family and the first proof of the idea.) The round idea, I have no idea. Harry again was given a dimension and showed up with the cut. He very much liked the cover. I would maybe do it differently now. I was looking at the book last night, first time in awhile and musing over design decisions.

He added: “Michele [Burgess, Brighton Press Director] just said the cover design idea was mine and hers was the color decisions. Sounds right.”

Harry had to be watched when it came time to sign and number the two editions. Bill remembered:

He even when signing our books would mis-number or swing something different. We had to have people sit with him to watch what he did carefully. Anna [Williamson–her mother Sue worked at the press at the time] often sat with him while he was signing, but she was more of a happy distraction than the person who watched and listened to all the stories that were part of the ritual.

The whole project, Kelly said, “took about two years, maybe a little longer. After the idea was settled on, the first blocks of the family leaving their villages was in our hands. The Statue of Liberty was early on. We were pretty excited by that one.”

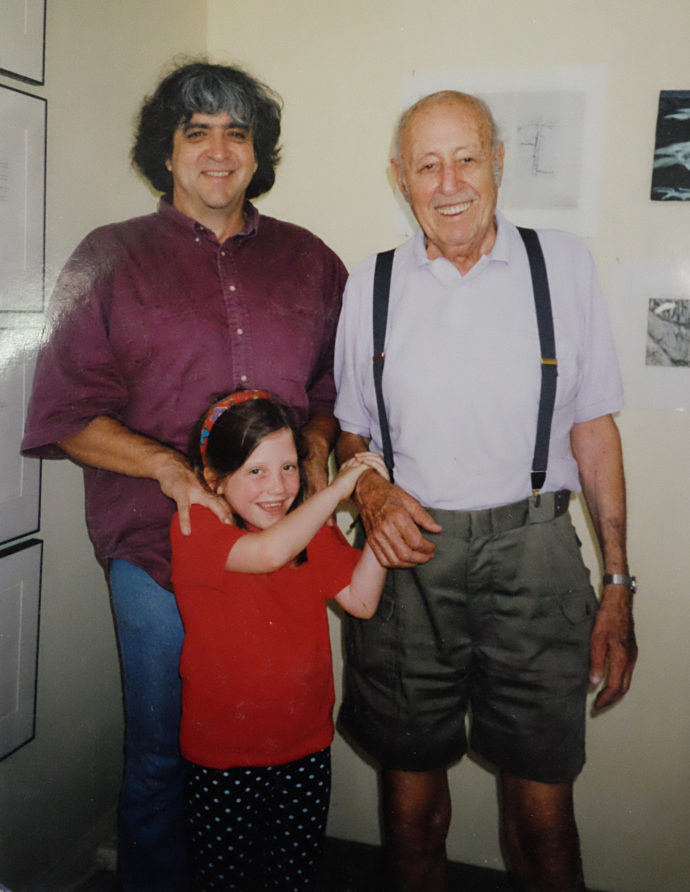

Bill Kelly (left) with Harry Sternberg and Anna Williamson, whose mother worked at Brighton Press. (Photo, c. 1990, courtesy of Bill Kelly)

In the end, Kelly said:

The book itself had many lives. Sales, exhibitions, travel, and meetings with all kinds of people who love books and prints. So many odd and interesting tales. The two editions seemed natural. One for the walls, and the other for the shelves.

This doesn’t always work out so neatly. Books are torn apart for the images, and collectors who want prints don’t really want books. Museums don’t really know how to display books, and you really can’t have masses of people turning pages. It has gotten better, and many places treat the book form quite respectfully.

Most collections that bought Harry’s book bought the version with the separate prints, and there have been many and lovely exhibitions of all the prints on the wall with the book displayed open to a page spread…. We like to think we sneak art into the libraries, and books into art collections. A wonderful book artist, printer and sculptor, Walter Hamady, called this the Trojan Horse of art.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/harry-bill-making-of-a-woodcut-autobiography/trackback/

Thanks for sharing your new precious acquisition.

As a person of Jewish ancestry whose ancestors likely

lived on the lower East Side in NYC,, I appreciated that

aspect of his work and his family photos. I hope to share this with my family.

Joan Sills

Dear Joan,

I wish I had obtained a copy of the Sternberg woodcut autobiography while my parents were still alive. It just might have served as a catalyst for them to related more about their upbringing in Brooklyn in the 1920s-30s. You’re more than welcome to come visit and leaf through the book and have the images come alive before you.

Sorry for the long delay. I’ve been away from my website and haven’t been getting notices when a reader leaves a comment. I’ve now begun working on the first of three posts related to my month in Italy last May.

yours,

Scott

Early in 1984 I went down to San Diego to show my work to some galleries. Everyone wanted color. One gallery owner directed me to The San Diego Print Club and Brighton Press as they liked black and white prints. Bill Kelly and I hit it off and we’ve been friends ever since. In 1985 I interviewed Bill for an article that appeared in the August issue of Newsprint, Los Angeles Printmaking Society. I also went down for the reception for Harry and the book. Harry was a real treasure, as are Bill and Michelle who continue to produce beautiful books.

Dear Richard.

Thanks goodness you made that trip to San Diego. What a wonderful experience. I’m envious. Have you ever tried working with Bill on a book?

And sorry for the long delay. I’ve been away from my website since the Sternberg post. And my website hasn’t been sending me alerts when a reader makes a comment. But I’m about to start a series of posts related to spending last May in Italy.

Scott

Scorr