Finlay Chairs? A question of attribution

Introduction

Ever since purchasing six Baltimore fancy chairs (above) in 1993 from Philip H. Bradley Co., I knew that someday I would replace them. The year 1993 was in the early days of becoming a collector of formal American classical furniture. And we were definitely new to appreciating and evaluating painted furniture of the day, a genre known as “fancy.” The beauty and value of fancy furniture is in the originality of the painted surface. We knew enough in 1993 to realize that the six wheelbacks had little in the way of visible original paint. But the form was great and each chair retained the original stamped brass boss nailed to the center of the “wheels” on either side of the seat. (A prominent antiques dealers knew of the set and was delighted that we bought them and would keep them as they were. She said she had a client who was considering having them entirely overpainted.)

In past ART I SEE blog posts I’ve shared my learning curve regarding painted furniture. The first in 2012 was: “Painted Furniture: Learning about Original Surfaces.” (LINK) Then came a post that begins with upgrading our six painted Windsor chairs for the kitchen: “2015 Recap: Decorative Arts.” (LINK) And most recently, a post described the cleaning of a high-back fancy chair that was probably used by a fraternal order: “2016: Marble Pier Table & High-Back Fancy Chair.” (LINK)

This post presents four Baltimore fancy chairs that were bought from an auction in Canada last summer. They definitely are an upgrade in original surface quality. They may even be from the shop of Baltimore’s best know makers of fancy furniture: John and Hugh Finlay. The operative word is “may,” as making attributions is a tricky proposition. This post discusses the possibility of an attribution.

Their purchase allowed me to find the very best home for my wheelbacks. I donated them to Riversdale House Museum in Prince Georges County, outside Washington DC. Years ago during a tour of Riversdale, I noticed in the library wing four wheelbacks that could well be from the same set as mine. So I wasn’t surprised that Riversdale was delighted to have them. The house was built between 1801-07 by Henri Joseph Stier, a Belgian aristocrat whose daughter Rosalie married George Calvert. A collection of Rosalie’s letters was published as Mistress of Riversdale, The Plantation Letters of Rosalie Stier Calvert by The Johns Hopkins University Press in 1991.

All photography is by Scott Ponemone except where noted.

Baltimore Chairs?

I guess the first question is: Were they Baltimore made? Still after 50 years, William Voss Elder’s 1972 book Baltimore Painted Furniture 1800-1840 remains a vital reference. While none of the chairs represented there have the profile exactly as my set, all of the components of my set are there. Item #48 comes the closest. It’s a Windsor chair (plank bottom seat), while my set has rush seats. In Gregory R. Weidman’s 1984 book Furniture in Maryland 1740-1940 (Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, MD) item #67 is a labeled 1827-42 chair by John Hodgkinson has almost an identical profile to my set, except it has a caned seat.

RIGHT: A yellow chair from the 1819 set made for James Wilson by Hugh Finlay at the Maryland Center for history and Culture (formerly the Maryland Historical Society). LEFT: A front leg from the yellow chair compared to one from my set.

And in Weidman’s 1993 book Classical Maryland 1815-1845 (Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, MD) Fig. 113 shows a yellow painted chair (caned seat) that has a profile similar to my set. It was part of a set made in 1819 for James Wilson. In part because a letter survives from Wilson’s son saying “Findley [sic] made the set of yellow furniture for the double parlor,” Weidman listed the chair as “Made by Hugh Finlay.” Weidman wrote: “The plain original paint was updated, probably when Wilson purchased the large rosewood grained and gold suite of furniture from Finlay a very few years later.” I pictured a leg from the yellow chair against one from my set because the profiles are almost identical and the leaf and berry design is the same. However in an email Weidman wrote: “I think you shouldn’t put to much weight on the decoration on the legs of the yellow Wilson chairs. They have had a substantial amount of repaint, as was noted in the catalog.” The leg decoration on a leg from my set appears to be original. Weidman is currently Curator at Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine and Hampton National Historic Site.

I also had contacted Alexandra Kirtley, the Montgomery-Garvan Curator of American Decorative Arts at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. She wrote back: “Anyway, it appears that the chairs on which your decoration is painted have Baltimore profiles; so safe to say they are Baltimore”

As to the date of my four chairs, I place them in the 1820-30 range. This is largely do to the rosewood graining found throughout the chairs except on the crest rails. Rosewood became popular around 1820. It was used by urban cabinet makers as a primary wood about then. Fancy furniture makers mimicked the rosewood look about that time as well.

Finlay Brothers

For a brief history of brothers John (1777-1851) and Hugh (1781-1830) Finlay, I turn to “The Furniture of John and Hugh Finlay,” a 2016 masters of fine arts thesis by Meagan Smith, at George Mason University. (LINK) Smith wrote:

“Older brother John Finlay began his career as a coach painter and was successful enough to take on an apprentice in 1801. Just two years later, John and younger brother Hugh announced the opening of their new shop in Baltimore’s Federal Gazette newspaper on January 25, 1803. They advertised a variety of what they called “fancy and jappaned” furnishings including various tables, seating furniture, and fire screens….

“From 1803 to 1841 at least one Finlay brother was at the helm of the shop. Their long tenure in the furniture business allowed them to experiment with different styles, and the Finlay’s shop went through three different phases. From 1803 to around 1810, the Finlay shop produced understated English-inspired painted furniture. The French Empire style crept into the Finlay’s work from 1810 through the beginning of the 1820s, which inspired an aesthetic that combined Greco-Roman motifs and furniture forms with the Finlay’s painted furniture from the decade before. The Finlays finished their career in the 1830s working almost exclusively with French designs.”

During their first phase: “One of the brothers’ earliest commissions was a 13-piece set which is associated with nineteenth-century Baltimore lawyer and banker John B. Morris…. This set that Finlays created around 1805 included ten armchairs, two settees, and a pier table.” The crest rails of the Morris suite include a cartouche of a prominent Baltimore area dwelling. Landscape painter Francis Guy is credited for painting the cartouches. Smith wrote: “Before moving to Brooklyn in 1817, Guy collaborated with the Finlay brothers and also created house paintings on commission.” Much of the set survives and can be found at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

The Finlays’ second phase started spectacularly. Smith wrote: “In 1809, British architect Benjamin Latrobe collaborated with John and Hugh Finlay to create furniture for President Madison’s drawing room at the White House. The set, which was once thought to be the first example of archaeologically-informed neoclassical furniture, included 36 chairs, 2 sofas, and 4 settees.” Unfortunately, when the British burned the White House in 1814, the suite was lost. All that survives are drawings by Latrobe, who was much influenced by the discoveries in Pompeii of Romans domestic interiors and by design books by Englishmen Thomas Hope and Thomas Sheraton. Smith wrote: “Influenced by their collaboration with Benjamin Latrobe, the Finlay brothers were happy to participate in this celebration of antiquity. Their work from 1810 to 1820 integrates Baltimore “fancy” furniture with French and English design sources.”

“Despite the brothers’ booming business,” Smith wrote, “the Finlay brothers dissolved their partnership in 1816. John went on to manage the “Pavilion Baths,” a classically-inspired club and bathing establishment, while Hugh continued the furniture business.” Hugh Finlay and Co. ended in 1830, when he died. Brother John stepped in and continued the business until his retirement at age 60 in 1841.

Just north of Baltimore is the Hampton National historic Site. The Ridgely family that built and owned Hampton turned to John Finlay in 1832. Smith wrote: “The commission from the Ridgely family that included 14 chairs, a sofa, a pier table, and a center table, makes up a large quantity of documented furniture from the Finlay shop’s last stylistic period.” The suite survives at Hampton. (LINK)

Finlay chairs?

What attracted me to the four Baltimore chairs was not only the condition of the paint decoration but also the very distinctive fruit and foliage stenciling and freehand painting of the crest rails. Not all of the paint was perfect on all four chairs. Two of them had later paint on the short posts of the chair backs and two had some touch-ups to the decoration on the front legs. But the showy crest and stay rails on all four were in remarkably good shape.

Here’s an easy comparison of two posts from the backs of two chairs from my four. It’s easy to spot the one with the untouched decoration. On the right, the profile of the gilded leaf has smooth edges and the articulation was done with unfussy strokes of brown paint. Also the rosewood graining is clearly visible above the leaf. All of that finesse is missing from the leaf on the left. Admittedly not all touchups are that pronounced on overpainted fancy furniture. But just seeing an untouched painted decoration on an early 19th-century chair is useful knowledge.

The rush seats happen to be original as well. Even here paint tells the story. There are traces of yellow paint on the top side of the rush, which is what you would expect since both rush and cane seats were often painted yellow. And on the perimeter of the underside of the rush seats there are areas of black paint, the first color applied to the wood to create rosewood graining. The seats were rushed before any painting was done.

The presence of rush seats on Baltimore painted chairs was uncommon but not unheard of. A set of six with possibly the exact profile as mine came up for auction in 2015 (LINK) As mentioned earlier Baltimore fancy Windsor chairs (with plank seats) happened too. In the 2021 book The Material World of Eyre Hall edited by Carl R. Lounsbury (Maryland Center for History and Culture, Baltimore) are photos of a Window settee and a Windsor chair that were bought for Eyre Hall, a manor on Virginia’s Easter Shore. And upholstered seats on Baltimore fancy chairs occurred too. In fact, my original set of six Baltimore chairs were made with exchangeable seat frames. One set of frames were caned (that was what was on them when I bought them) and one set (long lost) was upholstered. In fact, Elder pictured a wheelback chair (#24) in his book and noted: “The caned seat lifts out, adding to the tradition that, in Baltimore, these chairs were manufactured with summer [caned] and winter [upholstered] seats.” None the less, most commonly Baltimore fancy chairs were caned.

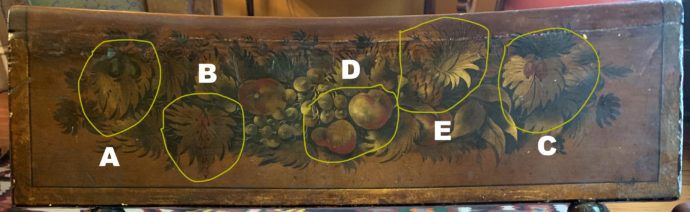

As I’ve said, I believe that the crest rails of my four chairs have distinctive freehand decoration, decoration that is found on a number of Baltimore fancy furniture that carry Finlay attributions. I’ve circled elements on a crest rail of one of my chairs that I find notable. A, B and C all have freehand painted fruit atop grape leaves. A has a pair of black/blue grapes. B has a bunch of currants or tiny grapes. C has a pair of red grapes. D shows freehand red highlights atop apples and/or pears. E shows a pineapple with a swirl of leaves and a freehand “scales” on the body of the pineapple.

On display at the Maryland Center for History and Culture (MCHC) is this Baltimore couch or ottoman, c. 1825 (1959.13.8). It is attributed to Hugh Finlay. A repetition of fruit and foliage stenciling and freehand painting decorates the seat rail.

This is a (composite) photo of a section of the couch’s seat rail. It’s labeled to note that all five elements–A, B, C, D, and E–occur in its decoration.

This Baltimore 1820-30 center table is in the collection of the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA 1992.214). The scenic scagliola top with oak leaf border was made by Della Valle Brothers in Livorno, Italy. (Scagliola involved making a mixture of ground gypsum and glue that was polished to resemble marble.) Hugh Finlay is credited for making the table. Originally it was part of an elaborate suite belonging to James Wilson (1775–1851), the same wealthy Baltimore merchant who also owned the suite of yellow Finlay furniture.

I’ve labeled a portion of its skirt to point out that A, B, C, D, and E are found in its decoration.

This Baltimore fancy card table also is documented as a product of Hugh Finlay and Co. In a 1995 article in Magazine Antiques, Ronald L. Hurst, then Curator of Furniture at Colonial Williamsburg, wrote an article “Prestwould Furnishings.” (LINK) Prestwould Plantation, located in Clarksville, in southern Virginia (which is open for visits: LINK) contains a number of furnishings associated to Sir Peyton Skipwith, who built the house (completed in 1795), and his family. Hurst wrote: “When the Skipwiths’ son, Humberston, and his second wife, Lelia, redecorated Prestwould in the 1830’s, much of the furniture was brought from Norfolk, Virginia, where Humberston had lived with his first wife, Sarah Nivison Skipwith…. Also brought from the Norfolk house was a fashionable suite of painted fancy furniture purchased in 1819 from Hugh Finlay of Baltimore. The suite included a sofa that is visible in early photographs of the house. Finlay’s invoices also list ‘1 pair card Tables,’ one of which remains in the house. Until the discovery of the Finlay furniture at Prestwould many closely related pieces were only loosely attributed to the Finlay shop. Now the connection can be proven.” Thanks to the Prestwould card table, the Wilson suite that included the scagliola-top center table could be labeled “made by Hugh Finlay and Co.”

In her thesis Smith wrote: “Another new decorative feature involved a shift from hand painting to stenciling. For example, the stenciled polychrome decoration of fruit and foliage on the table’s apron was a motif in development starting in 1819 when it was applied to a card table for the Prestwood family.” Smith said the use of stenciling “seems to have reached maturity in 1825.” She added: “The inspiration for the stenciled fruit and foliate frieze may have come from the artists who once specialized in miniature landscape paintings found in Baltimore furniture during the 1810s or from ‘fancy’ chair makers working in the 1820s.”

She commented that “The stenciled decoration on the Prestwood card table is … confined to one area of the table.” But when it is applied to the broad skirt of an ottoman or center table, it “fills every space and looks more like a garland.”

The stenciled and freehand painted fruit & foliage decoration on the Finlay table at Prestwould once again contains all of the motifs A, B, C, D, and E.

Only on Finlay products?

Because the fruit and foliage stenciling with added freehand painting is documented to Finlay furniture, can I claim that my four chairs are Finlays because they too have that distinctive decorative components? In fact, I can’t.

First of all, what is not known is who stenciled and painted that fruit and foliage decoration. Was it Hugh Finlay himself or more likely someone working in the Finlay shop, either as an employee or as an independent craftsman? William Elder in his book wrote: “In contemporary accounts, Hugh is mentioned as a gifted painter, and he might well be responsible for much of the decoration on the painted furniture in his shop. In one of the few documented references to Baltimore painted furniture, there appears another possibility; the name of a ‘Mr. Dereet’ is mentioned in a letter, surviving in the Massachusetts Historical Society, written from New York on 7 December 1825 by Rembrandt Peale to Thomas Jefferson…. Rembrandt Peale write: ‘For a while he [Debreet] he was engaged in Baltimore ornamenting Windsor chairs for Messrs Finlay when I became acquainted with him….’ ” Elder added: ” This name certainly refers to Cornelius de Beet who was listed in the Baltimore City Directory as a fancy painter or ornamental painter for there period 1810-40.” Then Elder speculates that, since de Beet was not listed in the Directories as an independent businessman between 1819 and 1829, “it seems that sometime in the ten year period, perhaps from 1820 to about 1825, Cornelius de Beet was under the direct employ of the brothers Finlay.”

In an email I turned to Alexandra Kirtley, curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art: “My question to you is: How unique is the fruit & foliage stenciling (and hand painting atop the stenciling) on my chairs to the Finlays? Bill Elder in his Baltimore Painted Furniture 1800-1840 mentions a Cornelius de Beet as a possible fancy painter for the Finlays. Do you have a further insight on the Finlays stencilers and painters?”

She wrote back: “These type of stenciled designs do appear in the Baltimore-Philadelphia region. I just spent some time trolling around the Winterthur manuscript library website—trying to find this wonderful collection they received several years ago—but I am afraid it is not on their site yet. Anyway, it was account books PLUS the actual stencils themselves of an ornamentor who worked for all the big chairmakers in Philadelphia. That is not to say that closely related designs didn’t show up in Baltimore, because they most certainly did! After all, ornamentors everywhere are copying the same European designs so….

“Anyway, it appears that the chairs on which your decoration is painted have Baltimore profiles, so safe to say they are Baltimore. However, do consider the other chairmakers working in the city on the 1830s. And yes, the Dutch trained painter Cornelius de Beet is one in a long, multi-generational line of skilled easel painters who DID paint chairs and other wooden works/furniture.”

I do have to remember that Baltimore was a thriving city after the War of 1812, and numerous cabinetmakers filled the demand for fancy furniture. Elder concludes his book with 34 pages of listings of “Cabinetmakers and Allied Tradesman Working in Baltimore 1800-1840.” A good number of them made fancy furniture. Some just turned out the wood components for fancy chairs, while others assembled and decorated them. There was an extensive division of labor.

The label of John Hodgkinson (1800-1858, working 1822-1857) is found beneath the front seat rail of this Baltimore fancy side chair, 1827-42. Except for the caned seat and the associated different shape to the seat rails, this chair’s profile matches that of my set. But none of the elements found on the crest rails of my chairs appear on this chair.

When I emailed a photo of the back of one of my chairs to Gregory Weidman and mentioned the MCHC ottoman and the BMA center table, she emailed back: “I would say you’ve taken all the necessary steps to investigate the connection with Finlay.”

If nothing else, I can firmly say that whoever decorated the crest rails on my chairs also decorated for the Finlays. While I can’t say my chairs were firmly a product of the Finlays, I can “attribute” them to the Finlays, or more precisely to Hugh Finlay and Co.

***

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/finlay-chairs-a-question-of-attribution/trackback/