EVAN LINDQUIST: An engraver’s Engraver

PREFACE

In shortened form, this post first appeared in the Spring 2016 edition of the Newsletter, a semiannual journal of the Print, Drawing & Photograph Society (a friends group of the Baltimore Museum of Art). New to this article is the artist’s comments about his engravings devoted to labyrinths and string theory. Also this online version makes checking out the links so much easier. Don’t miss viewing the YouTube video “Evan Lindquist Engraves Martin Schöngauer.” It’s very instructive to hear the artist describe his craft.

INTRODUCTION

While scanning the horizon for all things Hayter—that’s printmaker and Atelier 17 founder Stanley William Hayter (1901-1988)—Ann Shafer’s radar locked on Evan Lindquist. What attracted Shafer, BMA Associate Curator of Prints, Drawings & Photographs, was not so much Lindquist’s 40-year tenure as an art, printmaking, and drawing professor at Arkansas State University nor his appointment as Arkansas’s first Artist Laureate (2013-17).

“I can’t recall the context in which I first saw his work,” Shafer said via email, “but I remember posting his engraving Knight, Bird & Burin to my Tumblr a few years back. Then after I friended him on Facebook earlier this year, I saw his post of an image of the Hayter portrait. That’s when I first contacted him directly. …”

“I can’t recall the context in which I first saw his work,” Shafer said via email, “but I remember posting his engraving Knight, Bird & Burin to my Tumblr a few years back. Then after I friended him on Facebook earlier this year, I saw his post of an image of the Hayter portrait. That’s when I first contacted him directly. …”

Yes, what attracted Shafer to Lindquist was his engraved portrait of Hayter, the subject of her planned 2018 BMA exhibition and catalogue—a quest that started to take shape after the BMA acquired an Atelier 17 print in 2007. His 2015 engraving of Hayter is part of his continuing series of engravings of engravers that began in 2006 and now numbers, by my count, 17 images.

Evan Lindquist (Photo: Sharon Lindquist, 2015) ►

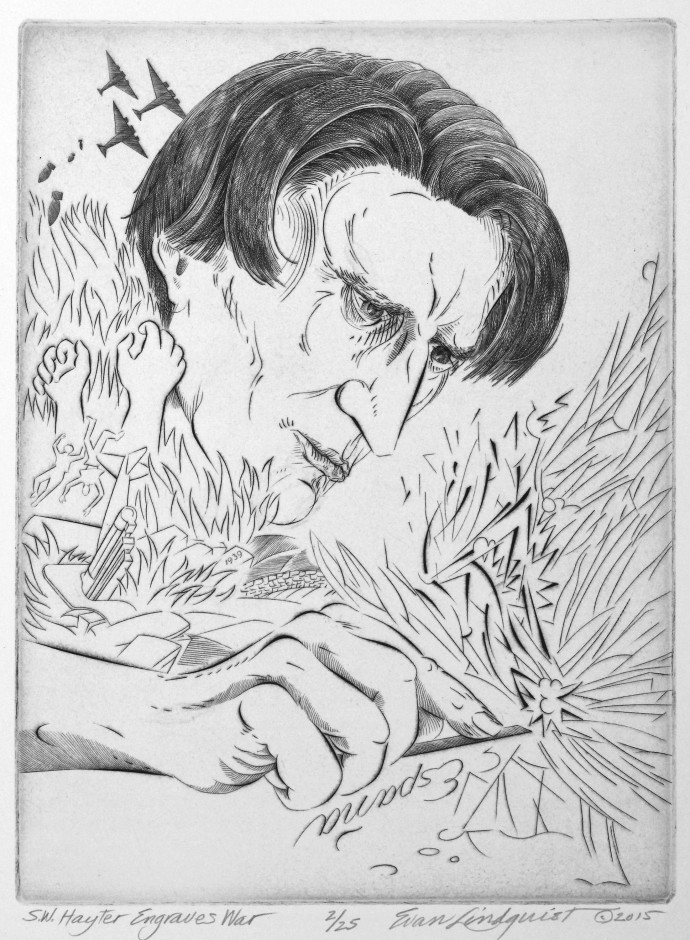

Thanks to Shafer’s online monitoring of Lindquist’s series of portraits, the Museum purchased his SW Hayter Engraves War last year. Asked why she would want to include a portrait of Hayter in the BMA collection, Shafer said, “I am pleased to be able to show the extension of Hayter’s legacy all the way up to the present day.”

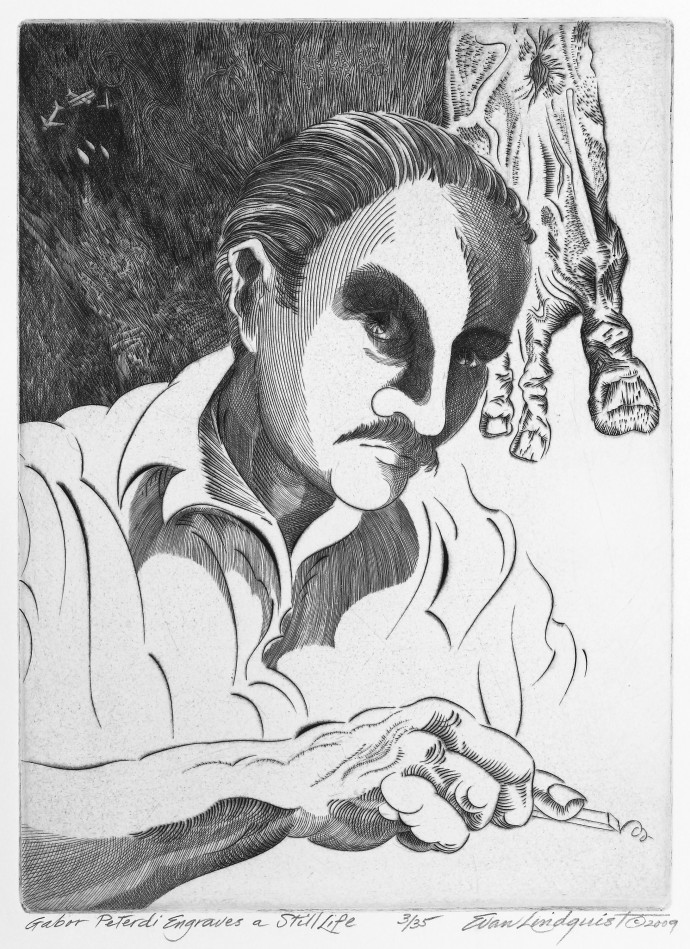

As a thank-you for the BMA purchase, Lindquist made a gift of his 2009 engraving Gabor Peterdi Engraves a Still Life. His generosity inspired me to contact him and seek out an email interview, to which he quickly agreed.

INTERVIEW

Evan Lindquist certainly didn’t retire from printmaking when he retired from ASU in 2003. His series of engraver portraits is a testament to that. Over his career he has had more than 60 solo exhibitions and has received more than 80 awards in about 300 competitive exhibitions. His prints can be found in over 70 public institutions.

In my November 2015 email interview, I worked chronologically from his early influences to his philosophy about engraving, to his schooling, and to his current series of engraved portraits.

How important was your father’s interest in calligraphy to your attachment to engraving?

He had wanted to be an artist, but the Great Depression and World War II restrained his passion. … His penmanship often consisted of calligraphic lines, flowing curves, and bold shades. Before I could read or write, I would lie on the floor and emulate those lines, but mine were just childish scrawls in crayon which I tried to perfect. Later I moved on to making those lines with ink pens. Years later, copperplate engraving was the answer to creating elegant lines. …

Calligraphy appears to be a dance of arm movement and hand pressure, while engraving requires the burin-holding hand to remain all but motionless. What type of struggle was it for you to bring the elegance of calligraphy to the copper plate? What mental adaptation was required to go from one medium to the other?

There are many expert engravers whose creative work results in beautiful calligraphy. I am not one of them. Engraving is my way of creating a new “vista”—an environment that appears and surrounds me as I create it.

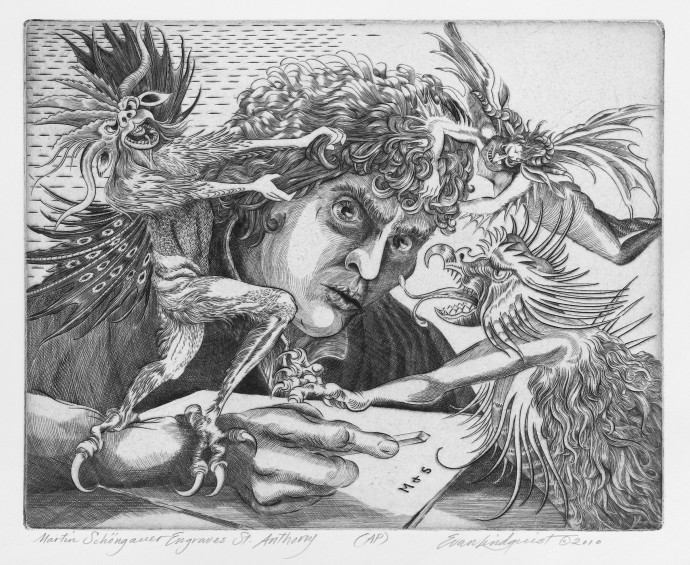

In the act of engraving, my eyes are close to the copperplate. My entire field of vision is a vista. I play within that environment. A struggle ensues between what I want to do as an artist and what I can do through burin-handling skill. If I were to rely on skill alone, the vista would appear cold and dead or in chaos. It is an important balance to maintain. I tried to present that feeling of adventure in my YouTube video “Evan Lindquist Engraves Martin Schöngauer.” [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MRFq5Y74TwY]

Frame-grab from the YouTube video “Evan Lindquist Engraves Martin Schöngauer.”

Evan Lindquist, Martin Schöngauer Engraves St. Anthony, 2010, ed. 35, burin engraving, image 8.3″ x 10.5″, paper Rives BFK. (© Evan Lindquist/VAGA NY)

The burin is a natural tool for making calligraphic lines, and I use it in a way that emphasizes its natural characteristics. Thus, my images make use of calligraphic qualities that would be impossible to duplicate through any other medium or technique.

What made you even interested in printmaking? Who introduced you to engraving?

During my earliest years my father would bring home drawing materials, scraps, from his lumber yard, for example, old wallpaper sample books and lumber crayons. I made prints with dozens of castoff rubber stamps and a stamp pad. When I reached the fourth grade in Emporia, Kansas, our art teacher introduced us to linoleum block prints, and I was in love with printmaking. In college [Emporia State University, Emporia, KS], Norman R. Eppink and J. Warren Brinkman encouraged my interest in printmaking and introduced me to engraving. I read two books on the subject, S.W. Hayter’s New Ways of Gravure, and Jules Heller’s Printmaking Today.

I understand one of your teachers was the engraver Mauricio Lasansky. Tell me about learning from him. What technical lessons did he provide? What mental lessons—apropos to engraving—did he offer?

Sharon [Lindquist’s wife] and I moved to Iowa City in July 1960. She had taken an art teaching position in the public schools. I bought a copper plate, studied the Hayter and Heller books, and began cutting a surrealist image into the plate. After a month of cutting, I walked into Lasansky’s first day of class [at the University of Iowa] and showed him my plate. He ran his fingers over the cuts and studied them closely. He asked some questions, now forgotten in the excitement of meeting the maestro. He turned and called out: “Jack, Virginia!” Two teaching assistants appeared. He pointed to me and told them in his soft, heavily-accented voice: “Make this boy a printer.” That was my personal invitation into the Iowa Print Group, and I was officially a printmaking major. …

Every student was different, and the Maestro dealt with each of us through private critiques. He might suggest that one student should try something, but recommend completely different ideas to the next student. There were also a few full-class critiques for anyone who wanted to sit in. During my years at Iowa it was an open classroom for students of all levels, and we learned from everyone.

The Maestro would choose prints to send to various national exhibitions, and an assistant would cut the mats and package everything for entering the competitions. This routine provided a few lines on our individual résumés and helped establish professional practices among the students.

Tell me about your set of rules for making an engraving.

My “rules” are a combination of instinct and experience—perhaps meaningful only to myself. My goal is to keep from getting into a rut. I know what has worked for me in the past, and lots of things didn’t work. But rules should be broken. Break any rule and it may provide variety to the work process and remind me that I should consider alternatives to the rule. The most important rule is that I must embrace failure as part of a creative process. In other words, try something that might not work, and then enjoy figuring out how to use any unintended result.

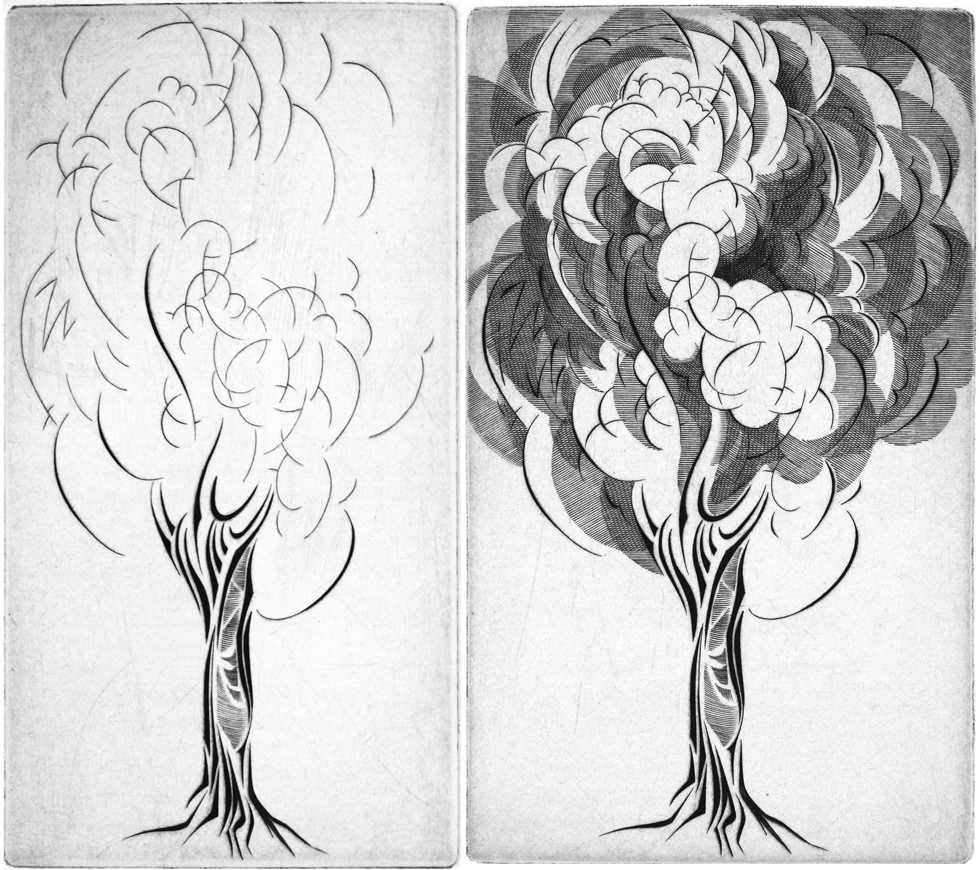

Evan Lindquist, Tree (left: state I; right: state IV & final), 2014, ed. 25, burin engraving, image 10″ x 6.1″, paper Rives BFK. (© Evan Lindquist/VAGA NY)

In your rules (in the 2010 Charles Kaufman article for the Society of American Graphic Artists) you say: “Only a few lines should call attention to themselves and be recognizable as ‘calligraphic lines.’ ” Yet some of your images emphasize calligraphic lines—like the recent tree prints. Why is that?

My personal definition of a calligraphic line is any line that stands out and shouts: “Look at me. I’m beautiful!” But how many “beautiful” lines would it take to throw a composition into chaos? A few calligraphic lines might strengthen and support each other, but too many of these lines would fight each other for your attention, becoming ridiculous or chaotic.

An example that illustrates this is my engraving, Tree (2014). A Japanese maple tree in front of my studio was the inspiration. In the first state of the print, every line has strong calligraphic qualities. The lines in the trunk are closely related, working together as a unit, forming a unique linear shape. In contrast, the foliage is a chaotic mess—too many lines, each begging for attention.

The finished state of Tree shows hundreds of new lines—straight lines, not calligraphic—that work in groups. Collectively, they describe shape, value, and space, organizing the earlier chaos into forms that suggest foliage. Each clump is enriched by a bold calligraphic line lending rhythmic character to the composition.

This example demonstrates that engraving a plate is a continuum. I begin each project with simple steps, then climb upward as the next step pops into my mind.

Describe your interest in labyrinths and string theory? What are you trying to say by producing those images?

Labyrinths and String Theories are two of my early series of engravings which continue today. The two series are closely related and overlap.

A labyrinth is a path that is complicated or difficult to follow. Labyrinths are mysterious. If you’re outside, you wonder what could be inside. Or what’s around the next curve? A labyrinth may conceal something. Mysterious thoughts from a viewer’s curiosity energize the labyrinth engravings.

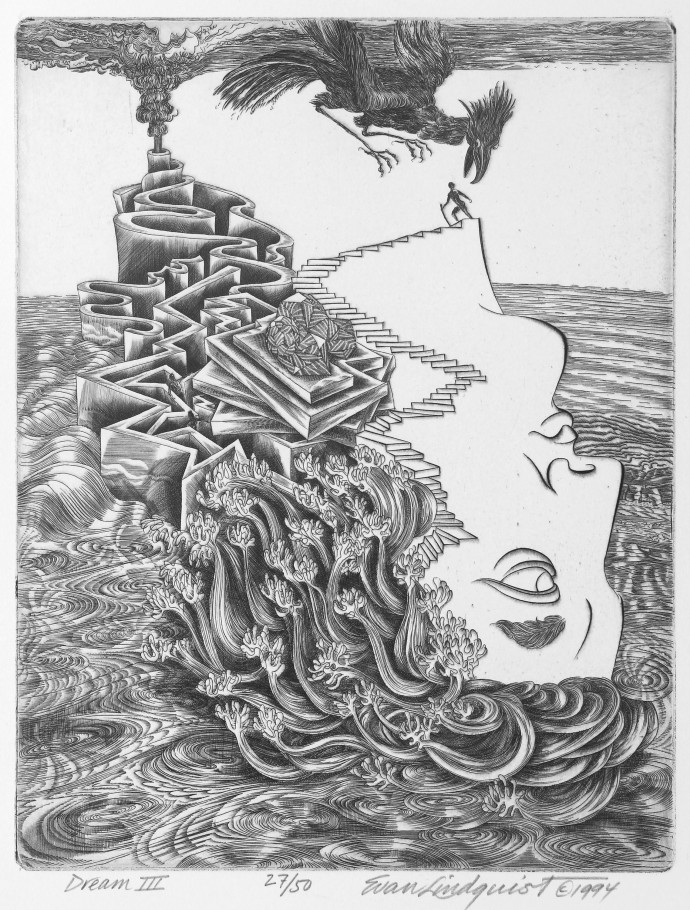

Evan Lindquist, Dream III, 1994, ed. 50, burin engraving, image 10″ x 7.8″, paper Rives BFK/Lana. (© Evan Lindquist/VAGA NY)

Dream III, 1994, contains a labyrinth that tells a story. I might describe it in this way. “An ancient hero has been decapitated by destructive forces unleashed upon a troubled world. Frightened people hide from the terror in a labyrinth that leads deeper into flames and smoke. One man climbs alone to confront the foul and terrifying thoughts that pollute the air.” Many questions are left unanswered to heighten the sense of mystery.

Evan Lindquist, Contemplation: Twist of Fate, 1994, ed. 50, burin engraving, image 18.7″ x 18.7″, paper Rives BFK Lavis a Grains. (© Evan Lindquist/VAGA NY)

Contemplation: Twist of Fate, 1994, is from a series of four prints bearing the title “Contemplation” to represent knowledge and the act of learning through contemplation of the world around us. The twisting strings are composed of calligraphic lines, thick and thin. No beginnings or ends are visible. The three strings symbolize the Three Fates in Greek mythology. They intertwine with the Future, which overlaps and twists around them. Because of a simple twist of fate, the best-laid plans may change for better or worse.

Other mysteries are found in the String Theories, which are are also examples of labyrinths. The String Theories are my attempts to give give physical form to invisible realities, such as Perception, Identity, Gravity, Id, Ego, Consciousness, Superego, to name a few.

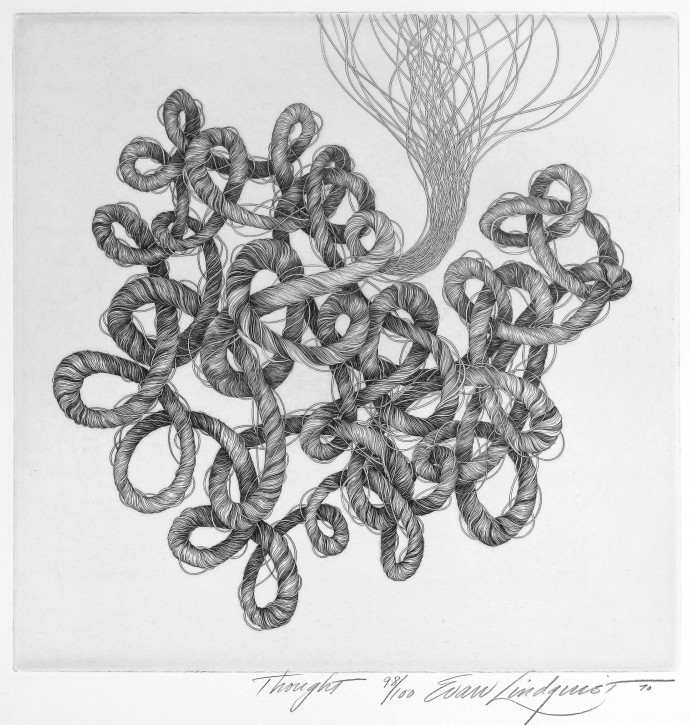

Evan Lindquist, Thought, 1970, ed. 100, burin engraving, image 12″ x 12″, paper Rives BFK Lavis a Grains. (© Evan Lindquist/VAGA NY)

Somebody once told me that every piece of string, must have two ends. Thought, 1970, was done to demonstrate that acceptance of such a rule places limits on what we are capable of perceiving. To counter that notion, I created an image of “one-ended” strings. Thought describes a succession of turns, like a string twisting through space, picking up new twists and turns as it descends from above. It is a labyrinth with no way out. It shows only one end, concealing the other, while retracing its path endlessly. It represents a thought that turns over in the mind endlessly without forming a conclusion.

Tell me about your series of engravings on engravers: why, when and how it began, who was chosen and why?

When I became interested in engraving in the 1950s, I was not yet aware that the history of engraving consisted of life stories of some old master engravers. I discovered that much of the information about them had been forgotten. Indeed, by mid-20th century, the entire medium of engraving was often dismissed as a “lost art.” I was determined to “find” it for myself.

Rather than considering engraving to be a “lost art,” I considered it to be a “forgotten art.” The postwar crop of printmaking teachers simply “forgot” how to teach engraving to younger generations. Even worse, the entire concept of printmaking was being regarded as an inferior form of art. Few contemporaries seemed to understand complex creative processes. Newer and faster processes took the place of engraving in art studios and classrooms.

S.W. Hayter attempted to revitalize engraving by teaching it to many important “new masters,” such as Gabor Peterdi, Mauricio Lasansky, and others, at his Atelier 17 in Paris and New York.

About 1980, I complimented Warrington Colescott on his series of prints called “The History of Printmaking.” Warrington said, “Why don’t you do the same thing for engraving?” Yes! That’s what I wanted to do!

But it took many years before I could settle on a plan that would have continuity. A tentative step into the series was Knight, Bird & Burin (2006). This led to Albrecht Dürer Engraves His Initials (2008), which seemed to be a good entry into a new series. Dürer was followed by Claude Mellan Engraves a Self-Portrait (2008). I saw potential for more old masters.

Evan Lindquist, SW Hayter Engraves War, 2015, ed. 25, burin engraving, image 10.9″ x 8.3″, paper Rives BFK. (© Evan Lindquist/VAGA NY)

A recent print in the series is SW Hayter Engraves War (2015). Hayter had been taught to engrave copper plates by Jozef Hecht, a Polish engraver. During the Spanish Civil War, Hayter produced prints to raise funds for the Republican war effort opposing the Nationalists, but after the bombing of Guérnica in 1939, the forces of Francisco Franco, supported by Hitler, took over the government of Spain. Nazis took control of France. In 1939, Hayter moved his Atelier 17 to New York City and taught many contemporary artists to engrave. Hayter is best known for many technical print innovations, but my engraving is focused upon his humanitarian war effort on behalf of the people of Spain.

Evan Lindquist, Gabor Peterdi Engraves a Still Life, 2009, ed. 35, burin engraving, image 10.6″ x 7.8″, paper Rives BFK Lavis a Grains. (© Evan Lindquist/VAGA NY)

A print closely related is Gabor Peterdi Engraves a Still Life (2009). This great Hungarian printmaker fled to America, became an American soldier and returned to Europe with U.S. forces. Peterdi was influenced by the horrors of Nazi atrocities when he engraved his biting satire, Still Life in Germany (1946). In the depressingly chaotic lines of the dark background in my engraving, I’ve woven “1938” and “1946”, referring to Peterdi’s years of despair and horror.

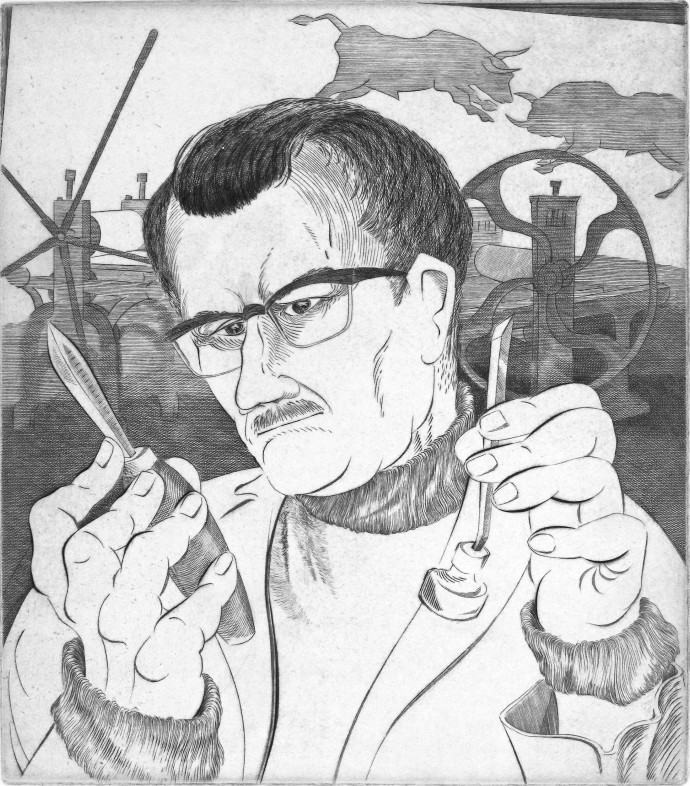

Evan Lindquist, Mauricio Lasansky Teaches Me to Engrave, 2015, ed. 25, burin engraving, image 13″ x 11.3″, paper Rives BFK. (© Evan Lindquist/VAGA NY)

The most recent print in the series is Mauricio Lasansky Teaches Me to Engrave (2015), a composite of memories. At this point it is the only one in the series that includes a medium other than burin engraving. In this print I’ve incorporated some small areas of drypoint—scratching into the surface with the point of a needle. The Maestro encouraged experimenting with a variety of processes to find new approaches to technical or aesthetic problems. I show him as he describes to me the importance of both the scraper and burin in the process of engraving—try anything with burin and scraper.

He had a love for fine, traditional, old presses, and every discussion of print aesthetics always included “print quality,” how well the plate was printed, how the press was used, how the paper was prepared, how the ink was ground and applied. Yes, we ground our own ink from dry pigments. I’ve alluded to all of these memories in my print by showing the presses.

Every critique with Lasansky would relate to the Old Master printmakers. The two bulls are reminiscent of Goya, whose legacy was nearly always brought into a critique and seemed always appropriate as an exemplar. There were framed Goya prints in the studio. Goya was never forgotten, but conversations also included Rembrandt, Picasso, Tiepolo, and other masters.

It is significant that the bulls are on the left side of the Maestro’s head. He often said that, no matter what he might be doing, the upper left side of his brain was always thinking about his current project.

What are your current print projects?

For my next engraving I agreed to begin a self-portrait for a museum exhibition next year. Early in the year I’ll also begin background research on my next Old Master engraver. I always seek new ideas.

What has been the advantage of concentrating on one particular medium over so many years? Why are you still in love with engraving?

This is what I was meant to do. It is what I do best. While engraving I find myself within the copper plate.

Each time I work with the burin, it is a new adventure.

LINKS

Lindquist website: http://evanlindquist.com

Evan Lindquist article by Charles Kaufman: http://evanlindquist.com/about/article-kaufman.html

Engraving links including YouTube videos on Lindquist website: http://evanlindquist.com/about/burin.html

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/evan-lindquist-an-engravers-engraver/trackback/

thank you scott for give me link this blogspot. All sketches its really amazing and say many things and thats so insipiring

I am an artist living in Portland, OR. I show at the Augen Gallery here in Portland. I started as a painter and moved back to drawing with pen and ink, in a print like style. My father was an international printmaker, and perhaps because of that I never made prints. Now in my older age, I am thinking of learning the trade, but perhaps it is not necessary now to my practice? It’s an emotional and technical commitment, and am not sure whether to go forward or not.

I love your work and sense my father is no longer around I thought I would connect with you as a fellow artist and printmaker, strange as that my seem.