Emma Bormann: A Family Affair

INTRODUCTION

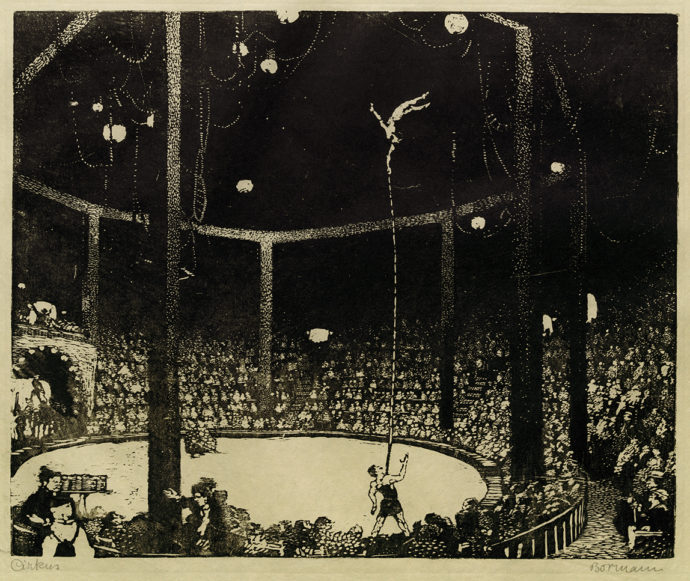

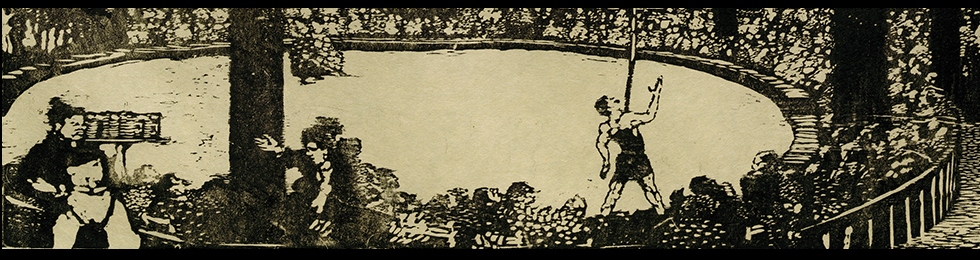

Thank goodness I started a reference library around 1980, near the start of my print-collecting obsession. Books like The Modern Woodcut by Herbert Furst (John Lane, The Bodley Head Limited, London, 1924) introduced me to the wonderful revival of relief printmaking that occurred early in the 20th century initially in Europe, then in the United States. Furst included four woodcuts by “Dr. Emma Bormann” of Austria: two theater scenes, one urban piazza scene, and one print simply called Circus. I was immediately drawn to both the precarious balancing act depicted in Circus and the nervous energy created by her mark-making.

Emma Bormann (Austrian, 1887-1974), “Circus,” woodcut, c. 1922, 13 5/8″ x 16 1/3″ (By permission of the Johns Trust)

Furst wrote: “She works with the grain on soft wood or linoleum white on black with short nervous digs which render lines [his italics] only by succession of white dots.”

Clare Leighton, another well-respected female printmaker (her forte was wood engraving), also illustrated Circus in her book Wood-Engraving and Woodcuts (The Studio LTD., London, 1932). Opposite the image of Circus, she wrote: “Here we get a rough-hewn, strong print, with no thought for delicacy or modeled form. There are no continuous lines, and the effect is got by nervous jabs with the gouge, of varying size and length and closeness according to how much light is needed.”

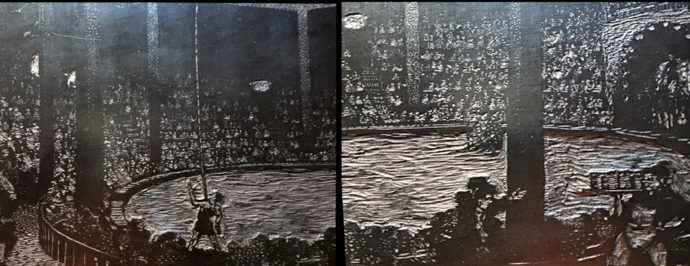

(left) Details from Bormann’s “Circus”; (right) Clare Leighton (British, 1908-1994), “Storm at the Fair,” wood engraving, 1937, 7″ x 4 5/8″ (Composite by Scott Ponemone. Left two photos by permission of the Johns Trust)

Here’s a comparison between how Bormann made her marks (left) and how Leighton did it. Leighton created energy with the direction of her lines and the tumult of the activity depicted. Yet her marks are all cleanly cut and often done in parallel strokes. With few exceptions like the elephant’s legs (lower right), her shapes are delineated with white lines. (I purchased Leighton’s print around 1980 from Betty Duffy at her Bethesda Art Gallery.)

These closeups from the finished woodblock for “Circus” provide an even better sense of the jabs she used to create her image. (Composite by Scott Ponemone. Photos by permission of the Johns Trust.)

Seeing Circus in Leighton’s book further stoked my desire to live with a copy of Bormann’s print. But decades went by without finding one for sale. I didn’t spot a copy until print dealer William Carl listed Circus on his website in 2007. Alas, it was “on hold.” And stayed “on hold” in early 2008, when I called Bill and he agreed to lift the hold and sell it to me.

When it arrived, I immediately framed it up and placed it in the guest bedroom, where the print selection had a circus/carnival theme. Both the Bormann and the Leighton hang there today.

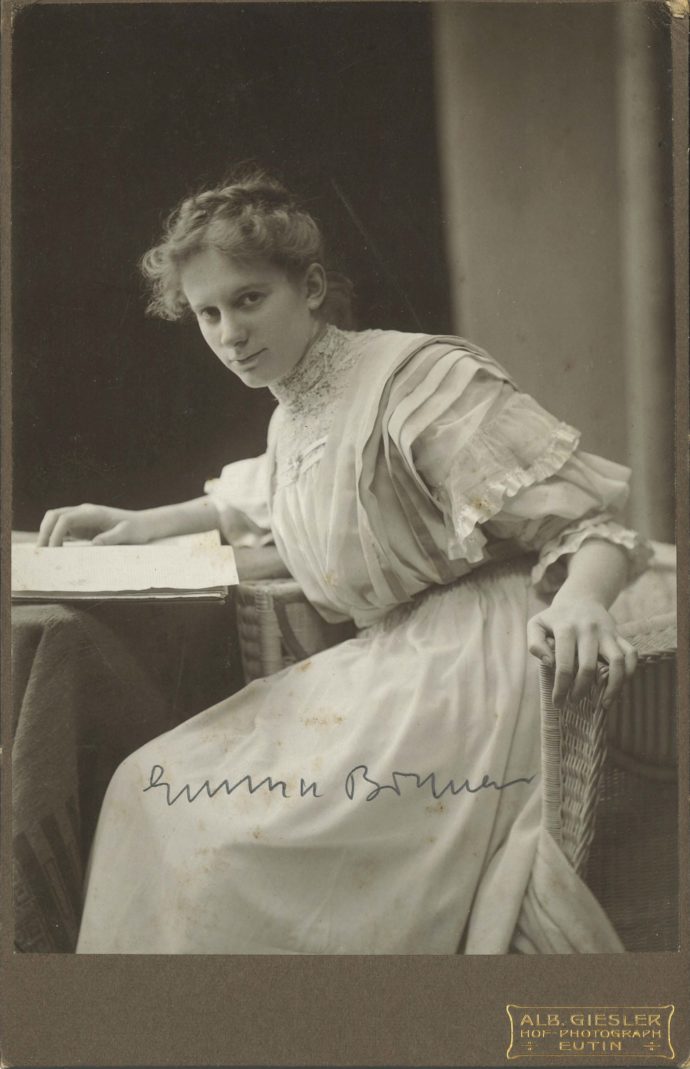

Emma Bormann, c. 1910 (By permission of the Johns Trust)

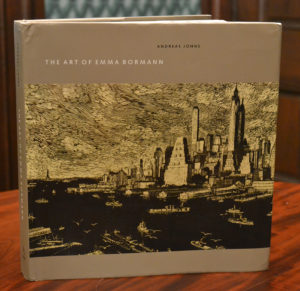

Over the years, what I knew about Emma Bormann had grown little since early on acquiring reference books like Furst and Leighton. Then great news for me. Last fall I learned that The Art of Emma Bormann was published in 2016 (Ariadne Press, Riverside, CA). I didn’t realize it until the book arrived that the author was a grandson of the artist.

So I read the essay that took readers from her birth into a bourgeois Viennese family in 1887, to her doctorate in prehistoric archaeology and anthropology in 1917, to her many travels in Europe, to her long residencies in China and Japan, and to her death in Riverside, CA in 1974. The author presented often lengthy quotes from contemporary European critics discussing her printmaking style. Best of all the book had over 150 full-page images of her art, mostly relief prints.

Making Contact

Despite all of that information on Bormann in both words and pictures, I wanted to know more, especially since the author, Andreas Bormann Johns, was a grandchild of the artist. Do you remember her? Are any of the artist’s children still alive? Did you ever see her make art? Why did you pursue the book? Are you the representative of the estate?

I soon tried to reach the author by asking his publisher to forward a message introducing myself and my blogging. No response that fall or winter. But one day this spring I decided to try again with an email to Ariadne Press. This time I got a reply with Andreas John’s email address. It was signed by Karl Johns. Below his name it read:

Jorun B. Johns

Ariadne Press

Photo by Scott Ponemone

So “The Art of Emma Bormann” was all in the family. I’m wasn’t sure who Karl was, but Jorun was in the book. She was one of Emma’s daughters.

“I’d be very happy to assist you with a blog post on Emma Bormann, with any information and/or images,” wrote Andreas Johns in his first email to me. He certainly has been good to his word. He also provided me with email addresses to both his brother Karl and sister Alessa. He even relayed questions to his elderly mother, Jorun Johns.

Andreas received his Ph.D. in Slavic Languages in 1996 from University of California Berkeley. He said, “I currently work for the administration of the University of California at the system central office in Oakland (the Office of the President). More specifically, I work for the Board of Regents, the governing body of the University.”

He said his mother is “a retired professor and taught German language and literature for many years at California State University, San Bernardino. She and a few colleagues founded Ariadne Press in 1988 to publish Austrian literature in English translation. The premise for Ariadne Press is that Austrian literature has a unique identity within the framework of German literature. The operations and oversight of Ariadne Press have now been taken over by my brother, Karl Johns.

Who was Emma Bormann

Here’s a very quick summary of Emma’s life. While it’s largely based on the essay in The Art of Emma Bormann, the Johns siblings as well as their mother Jorun Johns offered up additional details.

Emma Bormann’s father, Eugen Bormann (1842-1917), was an archaeologist and distinguished professor of ancient Roman history and epigraphy. He taught at the University of Vienna for 29 years. He oversaw several digs of Roman sites and frequently spent summers in Italy, taking students and likely Emma as well. “It was, said Karl Johns, “the life of the privileged and educated turn-of-the-century bourgeoisie who never cooked for themselves.”

Karl further commented: “Emma Bormann had the classical education in the house of her father, where all three daughters [Emma, Eugenie and Elisabeth] completed doctoral degrees. In their youth they attended the informal meetings of their father’s graduates discussing fine points of Roman history and during each vacation one of the children would accompany their father to Rome, where they stayed with a cousin living on the Corso working in a bank. They grew up knowing Rome like a second native place. Our great grandfather was a tall Prussian, the tallest in the group portrait of the founders of the Vienna Academy of Sciences…. The university tended to be anti-clerical as was Emma. She also played as an actress, toured Germany as the owner of the jug in Der zerbrochene Krug [The Broken Jug, a comedy by the German playwright Heinrich von Kleist], and grew up as an admirer of Karl Kraus in the liberal wing marked by much intermarriage.

“Her brother Karl Bormann, who died on the Serbian front in 1914, was also a good painter in an impressionist style. Her own impressionist paintings tend to have a stronger effect than the expressionist style.”

“Victoria Station London” (woodcut, c. 1923, 14″ x 19 3/4″) is an example of Emma Borman selecting a high vantage point for an image of a crowd. She may have picked this from Oskar Laske. (By permission of the Johns Trust)

In his essay in his book, Andreas Johns wrote: “Unfortunately, Bormann’s art study and training are not well documented. Her drawings and etchings from around 1913 show facility in rendering the human figure.” He noted that in 1913 she traveled to Sicily and Tunisia with a group from the University of Vienna, including artist Oskar Laske and Ludwig Michalek. “Laske, who liked to depict scenes of crowds viewed from above and whose figures sometimes tend toward humorous caricatures, encouraged her in her artistic efforts. Michalek was an accomplished etcher and painter … and his impeccable draftsmanship and accurate observation would certainly have made an impression.”

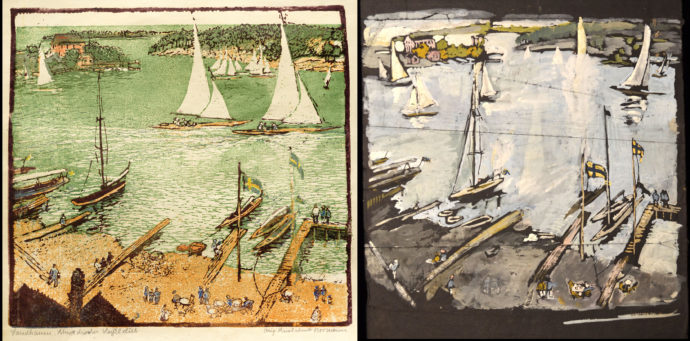

“Sandhamm, Sailboats,” color linocut, 13 1/4″ x 14 1/4″, with a preparatory drawing. (Composite by Scott Ponemone. Photos by permission of the Johns Trust.)

Emma Bormann made her first woodcuts during her stay in Munich from 1917 to 1920. In his essay Andreas Johns wrote: “She favored pear wood but also used linoleum; many of her multiple-plate color prints are linocuts…. Bormann appears to have preferred hand-printing to using a press because it allows for greater subtlety and control, with gradations of lighter and darker ink. She experimented with a baren, but was not satisfied with the results and used an ivory burnishing tool to rub the back of the paper, sometimes taking an hour or more to transfer ink to paper.”

Andreas Johns provided this recent photo of his mother Jorun Johns and himself.

Andreas relayed questions I had for Jorun Johns, his mother. I asked: Did you ever see your mother make a drawing or painting outside?

Yes, she made drawings that she would use later on. She used short pencils. She always saved little bits of pencils. She would use drawings to make paintings [and prints] later on. She would look at a city and make a sketch.

Did you ever see your mother print an impression of one of her prints?

She put the block on a table and rolled ink on the linoleum with a brayer, put a piece of Japanese [washi] paper over it, and carefully rubbed it, burnished it with a bone tool. Always by hand. She could make certain spots darker or less dark. She would have it under control.

Did your mother ever encourage you to make art?

She encouraged me to draw. She sent me to the Čižek class [Franz Čižek, artist, art educator, and pioneer in children’s art education]. He was well known. She took me there to draw. I made a few small linoleum cuts.

What did your mother ever talk to you about her art?

She said that it was hard. She didn’t just pretend this was nothing. I could see that her right thumb was quite overused, worn down from pressing on things.

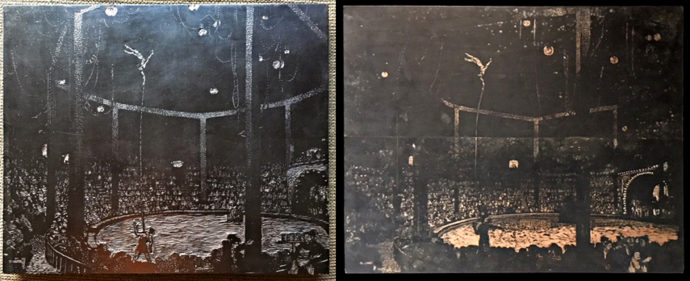

The woodblock for “Circus” (left) and an earlier attempt to create a block for “Circus” (right). (Composite by Scott Ponemone. Photos by permission of the Johns Trust.)

Here’s an illustration of how high Emma Bormann’s standards were and how hard she worked. Andreas Johns said, “There is an earlier version of the Circus print. The ‘white’ carved out areas on this block are very clear and visible, so she must have only printed from it once or twice and decided that she didn’t like it, and then started over again. This is not the only time she did this. She was willing to start over from scratch when she wasn’t satisfied, and I think it also shows that she must have been able to work quickly. Many artists might not ‘abandon’ a piece this size when it was more or less complete. The woodblock is broken and there’s some mold damage, but I thought you might find this interesting to compare with the final version.”

❋ ❋ ❋ ❋ ❋

The 1920s were years of great creativity for Emma Bormann. Her prints attracted critical attention as exemplified by the inclusion of four of her woodcuts in Herbert Furst’s The Modern Woodcut. In 1924 she married Eugen Milch (1889-1958), a physician who was a medical officer in World War 1. He knew Emma’s brother Karl.

About Eugen Milch, Karl Johns wrote, he “had participated in the earliest open-heart surgeries on the Serbian front in 1915. [He] was also a good painter, attended history lectures in Vienna and played cello in the opera when one of the professional philharmonic cellists was sick. He always assured her [Emma] that he put soap on his bow so as not to embarrass the orchestra. He regularly took the tickets available for a physician. We still have musical scores from China, where he rewrote the accents to play as trios with Emma and our mother Jorun on her small violin, which we also still have here.”

In an email Andreas Johns said, “My grandfather, Eugen Milch, was a practicing Christian but ethnically Jewish. My grandmother was Christian and their children were raised as Christians.” Emma and Eugen had two daughters, Jorun (born 1929) and Uta (1925-2007). In 1937 Eugen left for China with other Austrian physicians at the invitation of the Chinese government. The initial posting didn’t materialize, but in 1938 he became superintendent of a hospital and leper settlement in Pakhoi (now Beihai) China.

“Mei Lanfang,” hand-colored woodcut or linocut, 1940s, 8″ x 4″ (By permission of the Johns Trust)

Nazi Germany annexed Austria in the Anschluss of March 1938. Warned that she was on the Nazi blacklist, she fled Austria with her daughters and eventually joined her husband in China. Andreas Johns said, “My mother remembers riding out to the colony with him on a horse. While my grandfather visited his patients there, she went for walks….

“My grandfather’s sister, Stephanie Milch, was deported to the concentration camp at Theresienstadt, which she survived. While my grandparents, my mother, and my aunt had terrible, frightening experiences–such as Japanese bombing raids on Pakhoi (Beihai), where they lived before moving to Shanghai–I am tremendously grateful that they were spared this kind of fate, and the fate of many Allied citizens in Japanese-occupied China.”

In 1941 Japanese forces occupied 250 miles of the South China coast including Pakhoi. The Milch family managed to get to Shanghai. There Emma and Eugen decided to separate. He went on to assist British forces in China. He later became a ship’s surgeon and died in 1958 in Hong Kong as a British citizen. Emma and her daughters stayed in Shanghai, where she produced a number of prints including renowned Opera performer Mei Lanfang.

The Smithsonian mounted a solo exhibition of Emma Bormann’s artworks in 1947. Jacob Kainen, the museum’s Curator of Graphic Arts wrote in the exhibition announcement: “Dr. Bormann is one of the acknowledged contemporary masters of the wood-cut and enjoys an international reputation in the field. … Working on the soft plank or on linoleum, Dr. Bormann used [sic] quick nervous flicks of her gouge in the manner of an impressionist painter applying dots and patches of color. These small dots of black and white, however, merge and fall into place in her compositions, which are marked by a certain monumental and heroic quality.”

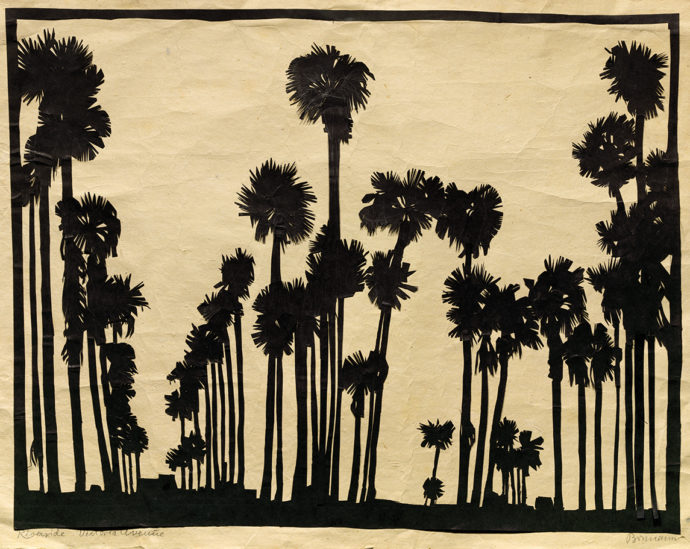

She left Shanghai in 1950 and traveled widely in Japan, Hawaii, mainland United States and Europe. Beginning in 1953 she stayed with her daughter Uta in Tokyo. She made her last relief prints in the late 1950s or early 1960s as she no longer had the arm strength needed to carve her blocks. Yet she took up new media, including screen-printing, mosaics and paper silhouettes.

“Victoria Avenue, Riverside, California,” paper silhouette, 1960s, 16 3/4″ x 21 1/4″ (By permission of the Johns Trust)

From 1958 until her death in 1974, she regularly traveled between her two daughters–Uta in Tokyo and Jorun in Riverside, CA.

Bormann’s dabbed on color in this painting–”Train Passing By, Riverside, California,” 1960s, oil on canvas, 23 1/2″ x 30″–with the same repetition that she gouged her wood and linoleum blocks. (By permission of the Johns Trust)

I asked Andreas Johns: To what extent was Emma able to support herself from sales of artwork.

I don’t know how much income my grandmother made from selling her artwork. From about 1926 to 1939, she had a teaching position at the University of Vienna as a lecturer for drawing and linocut techniques. At some point she also taught physical education at a girls’ school. Before my grandparents separated, she would also have had support from my grandfather’s income. In younger and later years, she was able to live and travel frugally.

My grandparents decided to separate while in China. I believe that after this, as soon as my aunt had finished high school-level education (she was older than my mother), she had to go to work to help support the family. My mother and aunt both supported their mother in her last decades.

FAMILY MATTERS

In this section the three siblings related memories of Emma Bormann, and Andreas discussed the creation of his book and estate issues.

Why, I asked him via email, did he decide to undertake writing a book on Emma Bormann. And when did his project begin?

This book is the result of a very long process. The walls in my parents’ home are covered with my grandmother’s prints and paintings. As a child, I took this all in but without really understanding it. I didn’t know what a print is or have any idea of the printmaking process. Only much, much later did I learn about printmaking, from taking classes at community art centers and community colleges, and from background reading and research. Until then I didn’t realize quite how much artistic vision, technical skill, and physical exertion are required to do what my grandmother did, and to produce these outstanding woodcuts, linocuts, etchings, lithographs, and stencil prints.

Around 1999-2000 I began to carry out an inventory of the prints in my family’s possession, and we gained a better overview of this collection. Besides understanding the printmaking process, I wanted to have a better sense of where my grandmother fits in the history of art. I looked through the materials we have from her lifetime: critical reviews and responses, exhibition catalogues, notes she made, and some letters. I also contacted and requested information from museums that have her works or where she exhibited. One dividend from doing the work on this book has been to learn about woodcut in the 20th century. The period when Emma Bormann was especially active, the 1920s and 1930s, was a very rich period for the woodcut, with many interesting artistic personalities, and many women, artists who are profiled or mentioned in the publications of Malcolm Salaman, Clare Leighton, Herbert Furst, Roger Avermaete, and A. van der Boom. Unfortunately, many of these artists seem to have been forgotten or nearly forgotten. I wanted to make sure this didn’t happen to my grandmother. Publications about her have appeared in Japan and Austria in the last few decades, but they’re not widely or easily available, and I sensed that there was a need for a substantive, representative book about her in English.

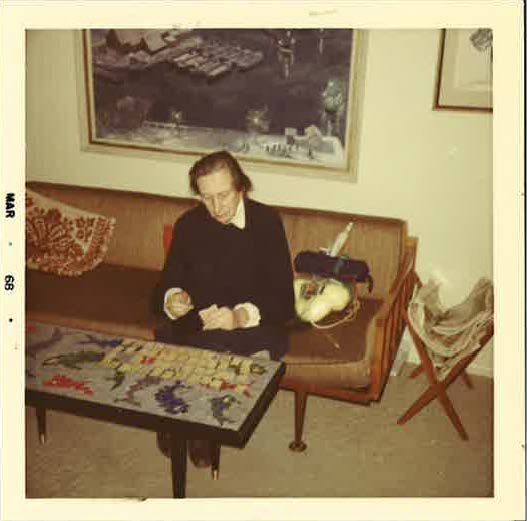

Emma Bormann, 1968. (By permission of the Johns Trust)

Can you tell me about your relationship with your grandmother? Did you see her often? Did you see her at her work? If so, can you recall how she worked? Did she maintain a studio in Riverside?

My grandmother died in 1974, when I was ten years old. I don’t have many memories of her. I remember her as an elderly woman who was weakened by illness–asthma and emphysema. She drew, painted, and cut out paper silhouettes, but she was no longer making prints. At this point in her life she went back and forth every six months between my aunt’s home in Tokyo and our home in Riverside, California. Her printmaking equipment was in Japan, not at our house….

I recall my grandmother as being a very strong personality, probably not always easy for the people around her. But in art, I think the strong personality had a good outcome. You can clearly see the influences of expressionism and impressionism in her prints, but with a unique personal twist. Naturally I’m biased, but when I look at how she handles the sky in many of her city views, I think, “an Emma Bormann sky” and I haven’t seen any other artist treat skies, or the sun, or buildings, quite in the way that she does. One thing that strikes me is how quickly she developed her own style in the woodcut medium, how quickly she moved in just a few years, from when she began making woodcuts in 1918 to around 1922-1925. Her early woodcuts have a rough, expressionistic quality, but within a few years, her treatment has become more impressionistic, with much more subtle treatment of lights and darks, transitions from one to the other, and extraordinary stippling.

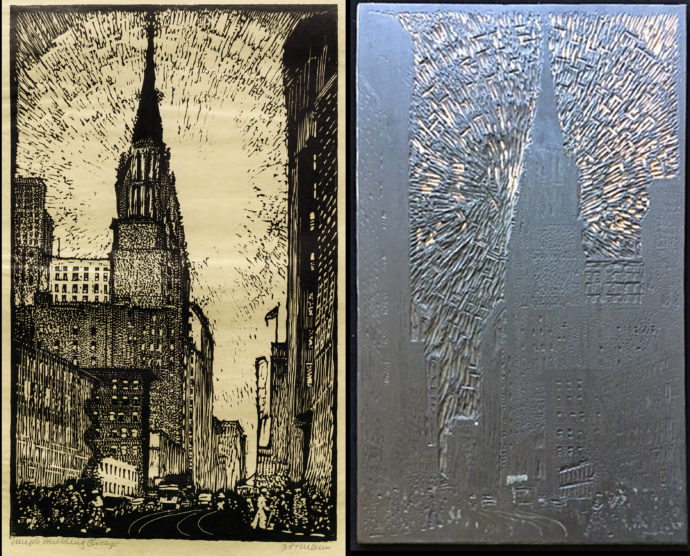

What Andreas Johns calls “an Emma Bormann sky” can be seen in the woodcut “Chicago, Temple Building,” 1937, and in the wood block that Bormann cut for the print. The image is 16″ x 9 3/4″. (Composite by Scott Ponemone. Photos by permission of the Johns Trust.)

The essay in the book ends with one memory I do have. I must have been about five or six years old. We were driving along the freeway in Riverside. My grandmother found the structure of the freeway overpasses interesting. My mother remarked that seen from above, freeway interchanges have the form of a flower, but my grandmother said she was interested in the view you have of the overpass as you approach in a car. This might have made my father, who was driving, a bit nervous, and he said, “No, we can’t stop on the freeway.”

Karl Johns is the Associate Editor of Ariadne Press. (He said, “As our mother gets older I am ending up with increasing duties in the Ariadne Press. I have worked with art museums in Europe and the US on specific exhibitions. My subject is Dutch Flemish art 16-17th century.”) He had this to say about his grandmother:

I am the older brother of Andreas and Alessa Johns, and with the age difference was able to know Emma Bormann a bit better than my siblings. One learned German to speak with her since the education in Vienna at the turn of the century taught people to read languages so that she was often difficult for people to understand in English…. When we knew her, her traveling and exhibiting days were over, and she was suffering from asthma whenever she would return from Tokyo.

In old age when she slept very little, she spent all of the time re-reading Goethe. She would begin laughing from the other room over a passage in Dichtung und Wahrheit (Poetry and Truth). She left a white thumb print on our father’s treasured copy of the Oxford Book of German Verse. We went for long walks to watch the people widen the interstate road to Palm Springs and other destinations and the women in the Bookmobile all loved to talk to her and brought the new art books as they arrived in the public library…. She liked the Jack LaLanne exercise show on television and always made caustic remarks about the way people dressed in Southern California…. [She] could touch the floor with both palms without bending her knees when she was 70.

By permission of the Johns Trust

Alessa Johns, Professor of English at the University of California, Davis, remembers this about Emma Bormann:

When I was in elementary school, my grandmother would come and sketch us kids as we played on the playground. From having grown up with her work, I know that it was just the type of scene she enjoyed capturing: dynamic, colorful, with a great variety of people in different poses, interacting with objects and with the setting in a lively way.

Alessa Johns with her mother Jorun Johns in a room with Emma Bormann paintings on the wall, May 2017. (Courtesy of Alessa Johns)

My grandmother would encourage me and my brothers to draw. She would give us a nice piece of sketch paper, and she would always draw a frame first, about a half-inch from the edge of the paper. My brothers were far more talented at drawing than I was, but I am sure she trained my eye. Growing up surrounded by her art was a great education.

She was a very active person. She painted, drew, and did paper cuts in Riverside. (Her hands had been weakened from the printmaking, so she couldn’t use those gouging tools any longer). She would knit. She would go on walks….

Except for her asthma, she was physically strong. As she got old I remember her asking me to make her some instant coffee, which she called “ein sanftes Herzmittel” (a gentle heart tonic). She was not a fan of television cartoons. She didn’t want us kids to watch them—I think she objected on aesthetic grounds. So I certainly grew up with a sense that one wants to surround oneself with things that are beautiful or interesting to look at.

I asked Andreas whether Emma Bormann’s estate resides at Riverside? Does some reside with her other daughter and that side of the family? Did some of her output get lost overseas (China, Austria)?

My family has some of her estate, in Riverside [Los Angeles suburb] and in northern California, where my sister and I live. My aunt, Uta Schreck [Jorun’s only sibling], died more than ten years ago. She and my mother had strained relations for a long time, with very little communication. I don’t have much contact with my aunt’s children, and I believe they have a significant number of prints and paintings. In past years, Uta arranged many exhibits in Japan, an exhibit held in Vienna and Beijing, and a book that was printed in Japan in the early 1990s.

We don’t know the full extent of Emma Bormann’s work. She was a very productive artist. Based on our collection, notes and lists my grandmother made, information from museums, and other published sources, and including small pieces, ex libris, ephemeral holiday greetings, etc., I’m aware of about 500 prints (woodcuts, linocuts, etchings, lithographs, and stencil prints). I’m sure some works have been lost, and there are certainly works out there that we don’t know about. Since the book was published, three works have come to light that we didn’t know previously: two early woodcuts, one in the Rijeka modern art museum and one for sale by an antiquarian bookseller, and a 1920 book of poetry that my grandmother illustrated, with what look like pen and ink illustrations, in a style unlike most of the work we know.

What does her estate contain, art wise: journals, sketchbooks, loose sketches, paintings, proofs of prints, finished prints, blocks and plates, etc.? What about tools she used to make her prints?

Not journals, but everything else you mentioned. The last set of tools she used is probably in Japan. I have a few etching tools she used when she was still living in Austria, and a wooden baren.

Did she leave records of her production, sales, public collections? You seem not to be able to report edition sizes.

We don’t have many records of sales, other than a few letters. According to my mother, my grandmother was cagey about how large her editions were. She almost never numbered them.

We also unfortunately don’t know how exhibits were arranged and how connections were made. For instance, she exhibited in London in 1922 at the European Art Publishing Society, which no longer exists, and in 1930 in Buffalo, New York, before her first visit to the United States in 1936. How did people in Great Britain and the United States find out about her work, people like Clare Leighton? It would be interesting to know, but that’s all been lost now.

[The Baltimore Museum of Art has five Bormann woodcuts in its collection, including an impression of Circus. All were given in 1928 by Blanche Adler, an important BMA donor. Where Adler came across Bormann prints and whether she met the artist are not known.]

I don’t think you quoted from Emma’s letters much in your book. Is there any letters/notes that you think would be of interest for me?

We don’t have many letters from my grandmother. I did summarize and quote a few letters that are in the Smithsonian archive and that the archivist sent me. My grandmother wrote to the Smithsonian Graphic Arts Division a few times in the early 1930s and then again after the war to Jacob Kainen, describing how prints and papers she had left in Pakhoi had been eaten by termites.

Are all the images of her work taken from work left in the estate? Did you have look elsewhere to get images? If so, did you do a fair amount of traveling for the book? If so, were any particular venues rich in her artwork?

Yes, all the images are from our family’s collection, except for one woodcut that my grandmother gave to friends of ours in Riverside. They very kindly lent me the print for photographing.

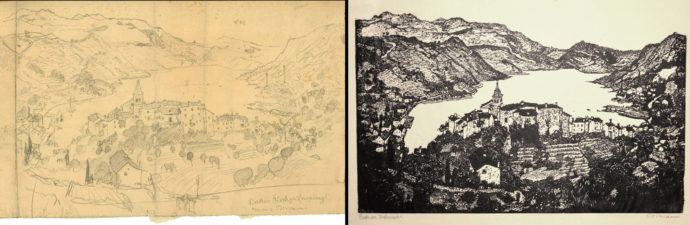

When I mentioned to Andreas that the Baltimore Museum of Art has a copy of Bormann’s woodcut “Bakar, Dalmatia” (10 3/4″ x 16 1/2″), he sent me images of the sketch (left) and the print. He didn’t illustrate this print in his book. (Composite by Scott Ponemone. Photos by permission of the Johns Trust.)

An appendix in your book has a lengthy list of artwork not illustrated. What was your selection criteria for including images in the book? Were some of her work known only by name, but no surviving prints could be located?

This was hard. It was very difficult to pare down the number of images, in order to keep the production cost down, to avoid overloading the book, and yet to ensure that, by looking through this book, you get a real overview of Emma Bormann’s work. I received good advice and feedback from my editor Frank Messina and designer Rob Hugel.

Some works are known to me only by name, from lists that my grandmother wrote up, from an article that appeared in a Croatian cultural history journal, and a list from an auction house.

Did you do all of your own translations?

I translated the German, French, and Croatian texts. Part of the background materials were in Japanese, short articles or catalogue texts, and these I had translated.

Has any part of the estate been given or promised to an institution?

No, it has not.

Have you and your family given any thought as to promising the Emma Bormann estate to an institution (or any thoughts on long-term disposition of the estate)? Would having part of the estate in Japan make such an effort problematic?

We haven’t thought about disposition of the estate in the future, like giving or selling prints to an institution. We might do so in the future, perhaps when we’re closer to departing the scene. We’re attached to my grandmother’s works, of course, because we remember her as a person. I enjoy seeing her work from day to day, as well as a few pieces by my grandfather and by my grandmother’s brother, both of whom were also quite talented.

My grandmother died intestate, so the artwork “estate” is really divided between my family and my cousins’ family. It’s not a single estate at this point.

Did you call on Uta’s children for help in researching your book? Did they provide images or share any of Emma’s letters?

As I wrote before, my mother and her sister had a fairly strained relationship for a number of decades. In addition, we’ve had a dispute with my aunt’s family about property (I have not been involved), which is unfortunate. I’ve had very little contact with my cousins in recent years. I did write to one of my cousins many years ago to ask if she’d be interested in collaborating on something. This was after there had been an exhibit in Beijing and Vienna, and a small book was published to accompany it, by Gerd Kaminski. My cousin basically replied “there’s already a book” so I don’t think she was interested. So Uta’s children have not contributed to this book. I of course drew on the material in the Kaminski book and in the book published by Shuichi Abe in 1991; my aunt was no doubt the motivating person behind getting that book printed, but other than one of the essays, I don’t know how much she worked on this, other than choosing and supplying the artwork.

Addendum: From Sketch to print

Andreas Johns was kind enough to send me some of Emma Bormann’s sketches that she used to create relief prints. What I noticed soon was that the sketches and the related prints had the same left-right orientation. Had she cut her blocks to match the orientation of her sketches, the resulting prints would have been reversed left and right.

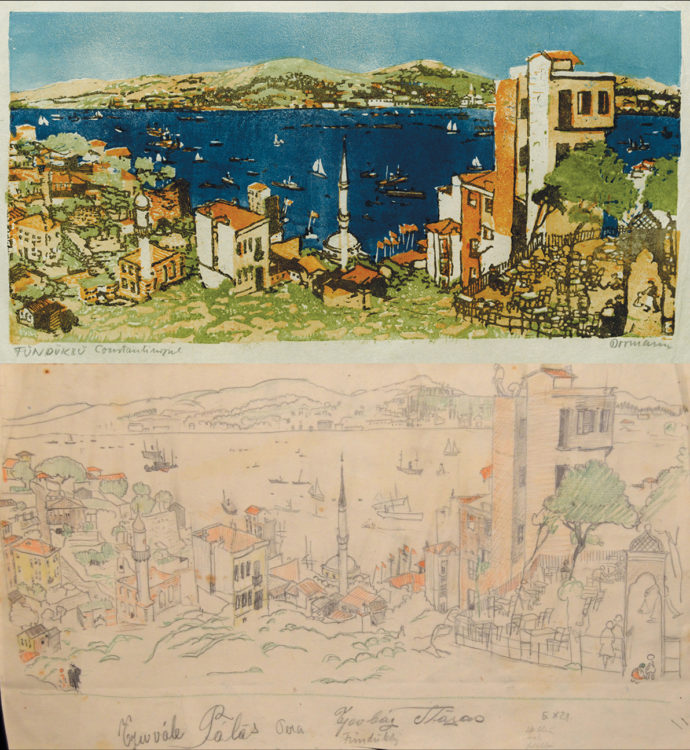

Composite by Scott Ponemone. Photos by permission of the Johns Trust

For instance, the Bormann’s color linocut “Istanbul, Fündüklü” (c. 1929, 8″ x 16″) and her preparatory sketch have the same orientation. So I asked Andreas:

What’s interesting is that the prints are not the reverse (left and right) of the sketches. So how did she transfer the drawing to the block?

I’ve noticed that there are outlines made with a blue pencil on the reverse of some of the sketches. In those cases, I think she flipped the sketch over and managed to trace the pencil lines onto the wood or linoleum. How she made sure that the pencil lines would become visible on the wood or linoleum surface, I don’t know. She may have painted a light color on the wood or linoleum (as some people do now), but I haven’t seen any traces of this on the wood and linoleum blocks that we have.

The reverse of Bormann’s sketch for “Istanbul, Fündüklü.” (By permission of the Johns Trust)

When Andreas sent images of the reverse side of three sketches, he added:

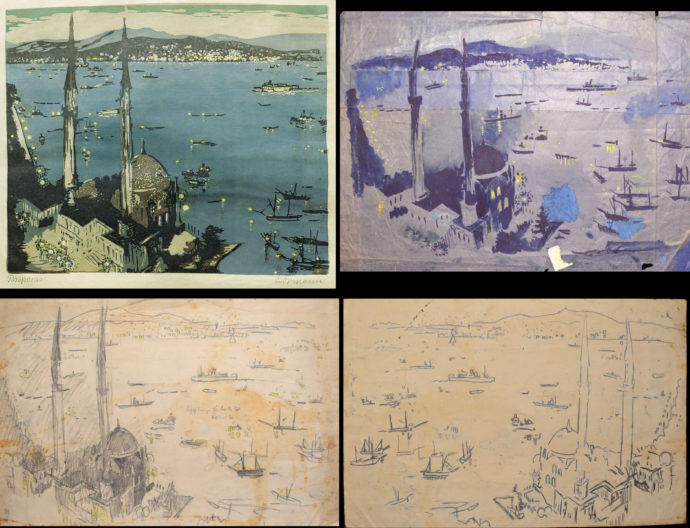

Here are the reverse sides of three of the Emma Bormann sketches, of Istanbul and New York. It looks like she flipped the sketch over and then transferred it to wood or linoleum. How exactly, I don’t know. The first step is to make this reverse sketch. Some of the sketches are on thin paper, and you might be able to see and trace the drawing if you held the paper against a window (or over a light box, which I don’t think she had). Other sketches are on more opaque paper.

Then there’s the question of how she transferred the image onto the wood or linoleum. Just the graphite itself wouldn’t show up very well on a block. I wonder if she used some intermediate step, like painting a wash of a light color on the block, and putting a sheet of carbon paper between the sketch and the block. For now that remains a mystery.

“Bosporus, Istanbul,” color linocut, c. 1929, 12″ x 14 1/2″ (top left) with a gouache drawing (top right), a pencil ketch (bottom left) and the the reverse of the pencil sketch (bottom right) (Composite by Scott Ponemone. Photos by permission of the Johns Trust.)

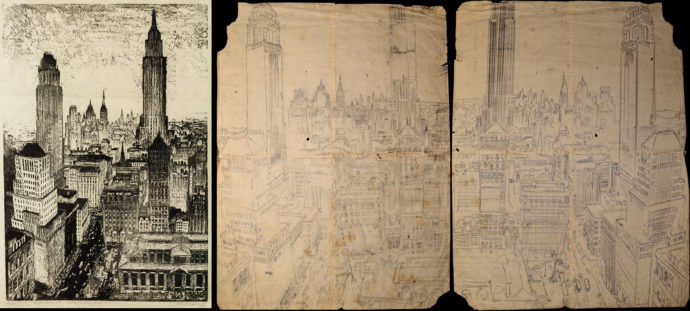

“New York, Fifth Avenue,” woodcut or linocut, c. 1937, 28 1/4″ x 19 1/2″ (left), the original sketch (middle) and the reverse of the sketch (right) (Composite by Scott Ponemone. Photos by permission of the Johns Trust.)

I realize now as I place these composites in this post that Bormann must have made her prints the same dimension as her sketches, otherwise marking up the reverses of her sketches would have served no purpose.

Then after asking yet another favor, Andreas sent me images of two of my favorite Bormann crowd scenes.

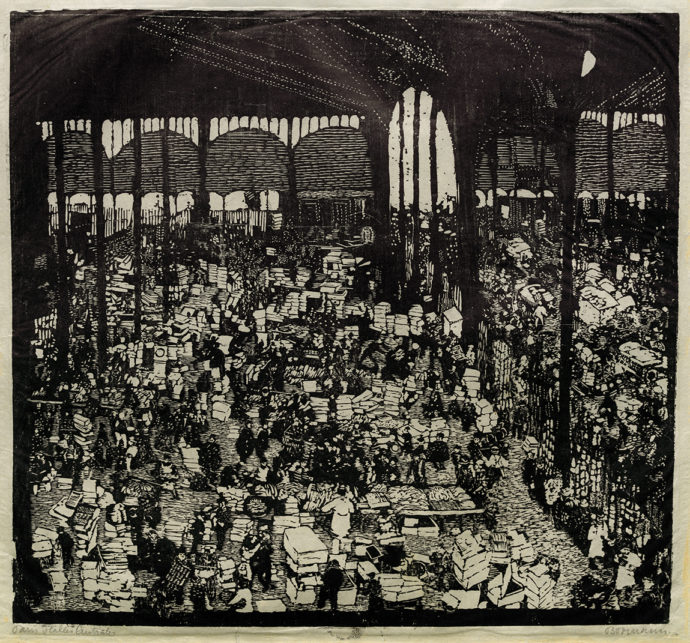

“Paris, Halles Centrales,” woodcut, c. 1931, 17 1/2″ x 19″ (By permission of the Johns Trust)

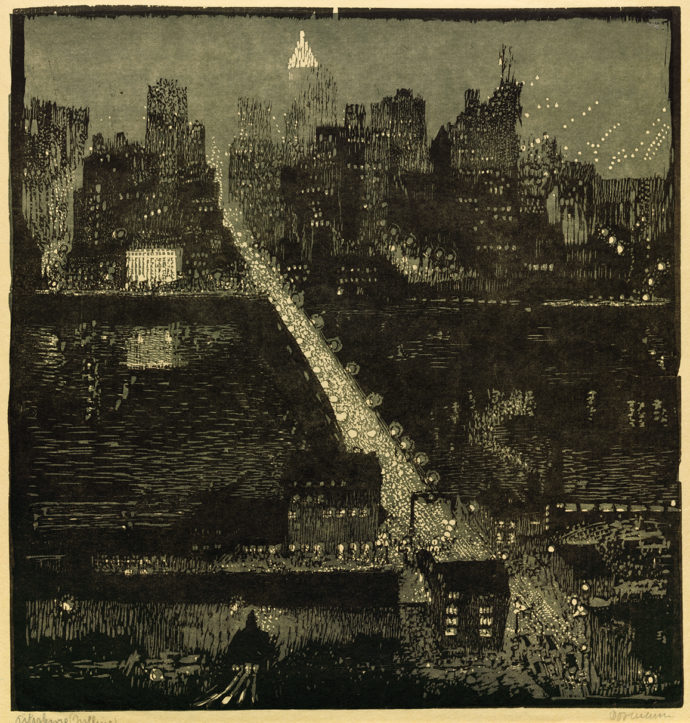

“Vienna, Am Hof,” woodcut, 1919, 16″ x 23 1.4″ (By permission of the Johns Trust)

And lastly, I asked him to send me an image of a uncommon example of Bormann making a relief print with just two colors.

“Pittsburgh, Incline,” color woodcut, c. 1937, 15 1/2″ x 14 3/4″ (By permission of the Johns Trust)

..

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/emma-bormann-keeping-the-flame-alive/trackback/

Franz Čižek died in 1946. It was Jorun Johns who was sent to his class by her mother Emma Bormann.

Jorun did some nice little paintings but never mentioned printing to me.

Kind regards from Klosterneuburg

Edith Specht