Eli Jacobi: Missed opportunity

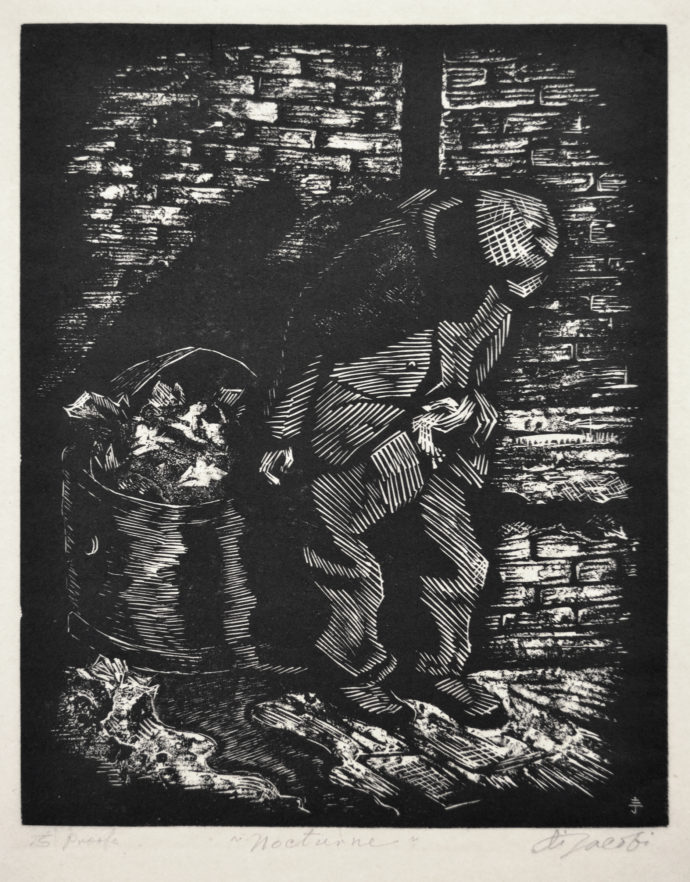

Eli Jacobi (Russian-born American 1898-1984), “Nocturne,” linoleum cut, 1936, edition 75, 9 7/8″ x 8″

Introduction

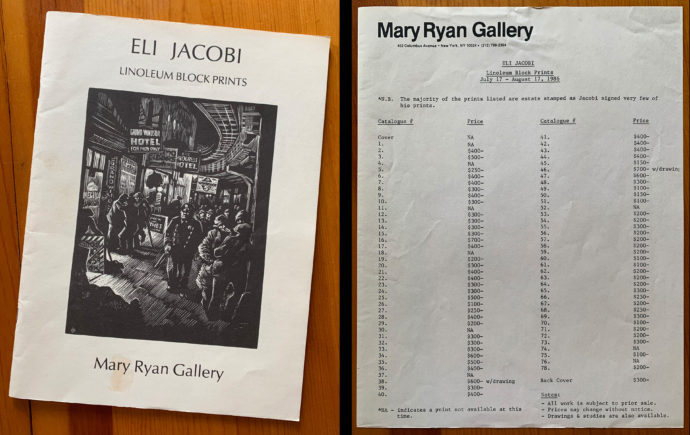

While I purchased this print by Eli Jacobi at auction last March, I first had an opportunity to select it 34 years ago when I arrived at the Mary Ryan Gallery in New York two days before the gallery held a retrospective of the artist’s linocuts, July 17-August 17, 1986.

When I walked in that July I was shown a stack of unframed prints by Jacobi, given a copy of the newly printed catalog for the exhibition as well as a price list. The catalog was in three sections: “Bowery Prints” with 53 items with dates ranging from 1935 to 1940, “War Prints” with 19 items dated from 1946 to 1951, and “City Views” with just 4 items and no dates given. Of the 80 items listed, only 9 were labeled NA–not available, i.e. sold. Seven of the NAs were in the Bowery series, none of the NAs were among the War prints, while 2 of the NAs were City prints.

If the pre-exhibition sales of the Jacobi prints are any indication of merit and interest, Jacobi’s Bowery images were his strongest. And the ones of those that sold before my arrival were evening street scenes like “Chatham Square” on the cover of the catalog. They tended to be peopled with down-and-out men and sometimes police, show illuminated business signs–often cheap hotels–and show girders of the elevated rail lines.

The Mary Ryan Gallery’s booklet still serves as the principal reference for Eli Jacobi’s printmaking oeuvre.

Jacobi and the Bowery

The Mary Ryan Gallery booklet on Jacobi includes a brief essay by Elisa M. Rothstein, preceded by acknowledgements in which she thanks Dr. Irving Jacoby (notice the difference in spelling), a nephew of the artist. She wrote that Jacobi was one of ten children born in 1898 to poor Jewish family in Kharkov in Western Russia. Thanks to a scholarship he studied at the Bezal’El Art Institute in Palestine before World War I. Then thanks to the American ambassador he went to Greece and became “a portrait painter for many of the Ambassadors in Greece. Upon completing a series of portraits of the Russian Ambassador’s family, Jacobi was offered the choice of enlisting in the Russian army or being sent to America. He chose the latter, and around 1920 found himself in New York.”

There, she wrote, he did a variety of jobs, both blue and white collar. He also studied at the National Academy of Design, the Art Students League and the Grand Central School of Art. “He began to do illustrations for magazines and newspapers in these years, and by 1926 had successfully established himself as an illustrator/caricaturist.”

In the early 1930s his paintings and early efforts in printmaking attracted “a small but expanding circle of patrons.” Rothstein wrote, “It was a short-lived luxury, however, for with the collapse of the stock market the Depression found Jacobi, and Jacobi found the Bowery–a street of forgotten men.” He was able to join New York City’s unit of the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration.

“In 1935, under there auspices of FAP/WPA, Jacobi began a study of the life he best knew how to document–life on the Bowery. A veteran of its sorrowful streets, Jacobi’s powerful series of linocuts form a remarkable document of human suffering, and of courage in the face of awesome adversity.”

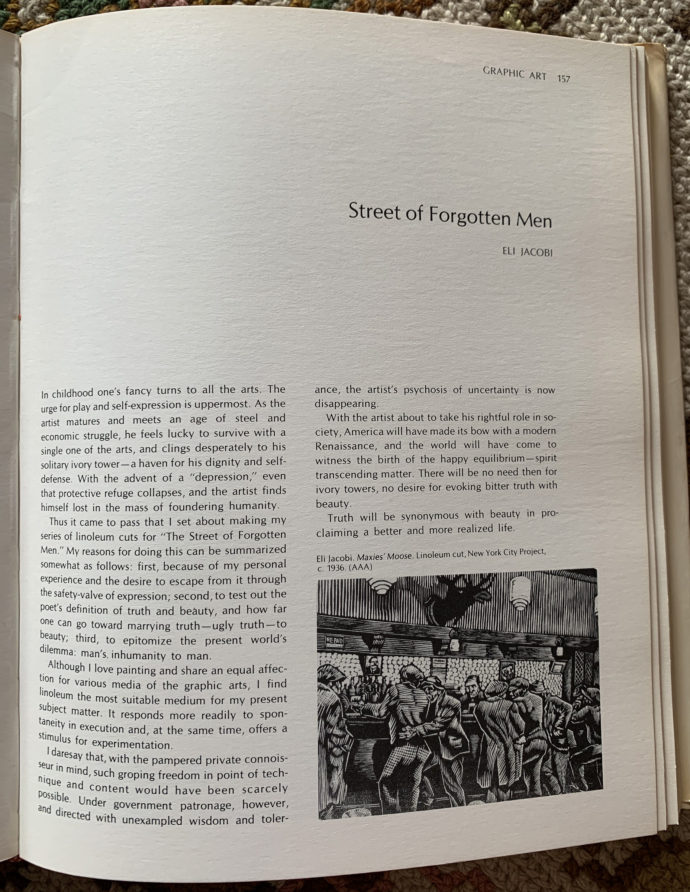

She then quotes two paragraphs from “Street of forgotten Men,” an essay by Jacobi in Francis V. O’Connor’s book Art for the Millions: Essays from the 1930s by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project (1973, New York Graphic Society Ltd, Greenwich CN). So I obtained a copy of the book and was somewhat disappointed that Jacobi’s entry was just one page. Jacobi wrote:

As the artist matures and meets an age of steel and economic struggle, he feels lucky to survive with a single one of the arts, and clings desperately to his solitary ivory tower–a haven for his dignity and self-defense. With the advent of a “depression,” even the protective refuge collapses, and the artist finds himself lost in the mass of foundering humanity.

Thus it came to pass that I set about making my series of linoleum cuts for “The Street of Forgotten Men.” My reasons for doing this can be summarized somewhat as follows: first, because my personal experience and the desire to escape from it through the safety-valve of expression; second, to test out the poet’s definition of truth and beauty and how far one can go toward marrying truth–ugly truth–to beauty; third, to epitomize the present world’s dilemma: man’s inhumanity to man.

Although I love painting and share an equal affection for various media of the graphic arts, I find linoleum the most suitable medium for my present subject matter. It responds readily to spontaneity in execution and, at the same time, offers a stimulus for experimentation.

According to the biographical notes at the back of the Mary Ryan catalog, in 1939 prints from “The Street of Forgotten Men” series were shown at the Print Club of Philadelphia’s 12th annual Exhibition and in the 7th International Exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago. And five of Jacobi’s Bowery prints were published in the Federal Writer’s Project WPA Guide to New York. Then in 1953 his print City Nocturne–which may be the same as Nocturne, the print I bought–won first prize from the International Artists Group.

From the catalog section Notes on the Prints: “Based on technical descriptions written by Jacobi, … we can surmise that Jacobi did all of his own printing. Jacobi also made lithographs and color woodblock prints…. He also executed detailed preliminary drawings for several of the Bowery prints. His edition sizes never exceed 100 and in many cases only a few impressions were pulled. Because Jacobi usually signed his prints as they were sent to exhibitions or sold, most of his prints were unsigned.”

Back to 1986

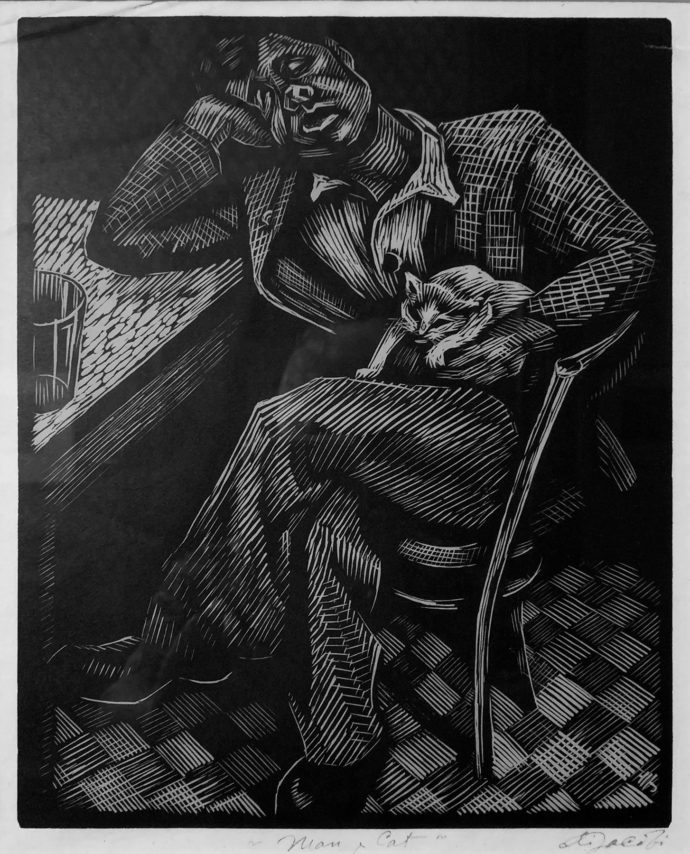

My only purchase from the stack of Jacobi prints offered to me in 1986 was Man & Cat. If I had my collector’s cap on that day, I would have bought it plus the best of the remaining nighttime street scenes and one of the barroom scenes. That would have covered the spectrum of his Bowery images. Then again, at the time I was working part-time as a copy editor for the Baltimore Sun and the $200 for Man & Cat was not throw-away money. Ironically, when I did acquire Nocturne, my second Jacobi, it would be another image of a single man, however this time outside.

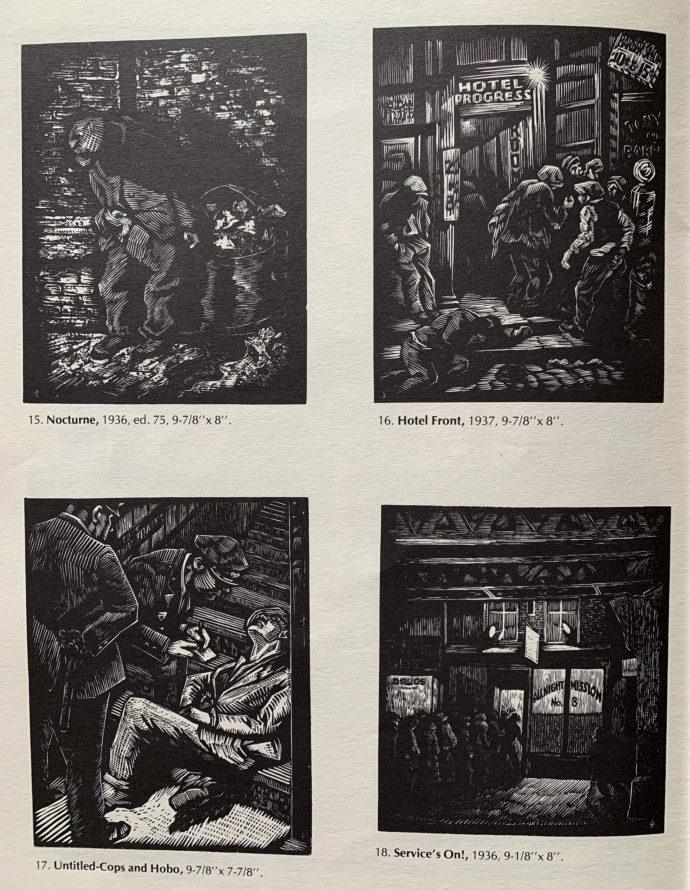

I’m always curious about how things get priced, especially works of art that have been off the market for a long time. Above is Page 8 from the Mary Ryan Gallery catalog. (Note that Nocturne was printed in reverse.) Here are the 1986 prices: #15, Nocturne, $300; #16, Hotel Front, $700; #18 Untitled-Cops and Hobo, $400; and #18, Service On!, NA (likely at least $700). I left a message via the Mary Ryan Gallery website hoping to ask how the gallery went about pricing the prints in 1986, but I’ve not received a reply. Esthetically speaking, was Hotel Front worth more than double the price for Nocturne? But I realize that esthetics are not necessarily a marketing tool. Galleries need to know the market, and New York street scenes have always been awarded a high value.

By the way, I paid $409.06 (including buyer’s premium) for Nocturne at auction last March. An image like Hotel Front could retail for $3-4,000 today.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/eli-jacobi-missed-opportunity/trackback/