Down to the Bone

This interview first appeared in the fall 2012 Newsletter of the Print, Drawing & Photograph Society, a friends group associated with the Baltimore Museum of Art. I’m the author and photographer of this interview and editor of the twice-yearly Newsletter. Information of the society can be found at: http://www.artbma.org/friends/pdps.html. A PDF of last spring’s Newsletter can be accessed at this location.

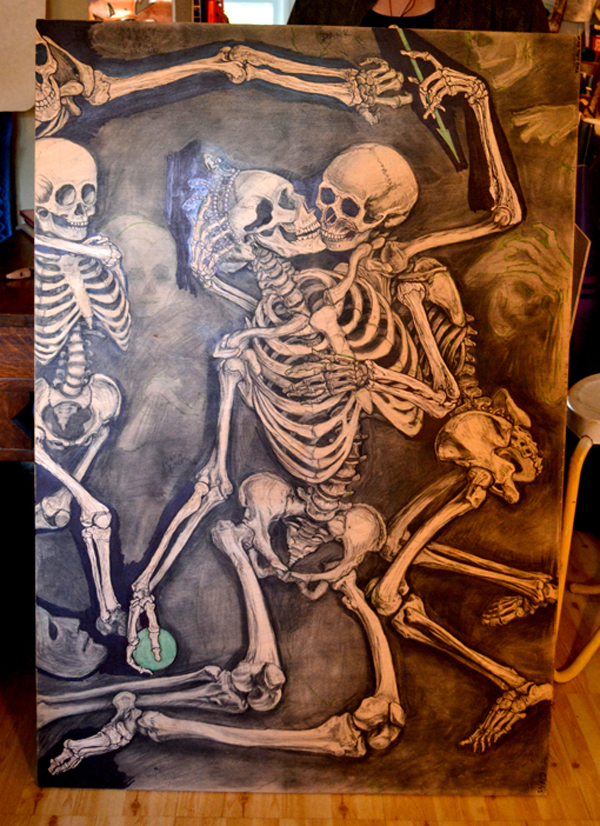

Trudi is at it again. And it’s big! And it’s bones!

In the fall 2000 issue of the Newsletter I had the honor of introducing Trudi Ludwig Johnson’s work to PDPS members. She had used her x-ray vision to turn the three graces of Sandro Botticelli’s Primavera into a 36” by 48” woodcut of dancing skeletons. Curator Susan Dackerman was so impressed that she chose to add Prima Veritas–as Trudi called her work–to the Museum’s print collection.

Since then Trudi has cut additional skeletal-themed woodcuts but nothing as dramatic or ambitious as Prima Veritas. Yet for a few years now she talked about another mega-effort. And I–I admit–have prodded her some. I’ve told her: “I’ll trade you a painting for your new woodcut.”

I’m glad to report that she’s at it again, big time. She invited me to her house in July to photograph her work-in-progress and later was gracious enough to answer some questions I sent her. Here are her replies:

< Agnolo Bronzino (Italian)

1503-1572

An Allegory with Venus and Cupid

about 1545

Oil on wood

146.1 x 116.2 cm

The National Gallery, London

Bought 1860

Whose image are you working from, and why did you choose it?

The iconic painting by Agnolo Bronzino, Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time, circa 1546, is the foundation of my woodcut. Its astonishing, improbable, centrifugal composition is emblematic of the Mannerist modus operandi in the late Italian Renaissance. One of the alternative titles this image has obtained over the centuries is The Exposure of Luxury, which is what I’ll be calling this finished print. My work almost always involves humor at some level, and the layering of wordplay and visual imagery may trigger some self-reflection in contemporary viewers.

What is your history with skeletal imagery, and what attracts you to it?

The long answer is that from elementary through high school I was active in ballet and gymnastics. I spent hours and hours looking at the human body in motion and marveling at the “machinery” that made such beauty possible. I was also drawing this whole time, savoring the see-through overlays in the anatomy section of the Encyclopedia Britannica we had at home, and falling in love with the tangible glories of human biology.

Fast forward into an MFA program in printmaking and drawing. When searching for content in my work, I used the minuscule inheritance from my father’s passing to purchase Dead Bob, a flexible-spine skeleton (cast from human bone). For years I had been asking my art history students to imagine what the bones looked like under the figures of Old Master paintings. I wanted to see what the bones looked like under the three graces in Botticelli’s Primavera. I wanted to see what that re-contextualization would produce.

Even though I’d drawn the image on the wood, I tabled the project during grad school and never carved it because I had buckled under to faculty resistance. Your prodding, Scott, forced me to actually do it. When I take my MICA students to the BMA for History of Prints class, we bring out Prima Veritas and I use it as an opportunity to spin a parable about sticking to your guns and believing in your ideas and being patient.

The figures in Prima Veritas are lifesize because I wanted the viewer to look death in the eye and dance the dance while they had the chance. I finished Prima Veritas shortly after I turned 41.

In 2006 I had lightly sketched the outline for The Exposure of Luxury on the wood, but didn’t have the time, or the priority, or the clarity, or the courage to tackle this ridiculously large, difficult, long-term project. It sat in a closet until this past January.

How do you go about taking an image of nudes, turning them into skeletons, and then enlarging the image to fit your block that’s 32 13/16″ x 48″?

I used a now-dead technology: I took a slide, put it in a projector backwards and projected it to the size I wanted on a piece of birch plywood. I traced around the fleshy figures. The outlines had to be in reverse so that the subject of the original image will appear right-reading in the final print. Because I wanted the skeletons in The Exposure of Luxury to be life-size on the block, I focused on the passage of the Bronzino that delighted me most. And I also reserved the right to edit out details as I saw fit.

How long did it take to create the drawing, and where and when did you do it?

The actual charcoal drawing of the skeletons was done this past spring semester while I was Artist-in-Residence at the Luce Center for Art and Religion at Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington, DC. Two wonderful days a week I was in the studio. I’d arrange Dead Bob (or parts of him) and draw. Just looking and drawing. And they let me do it! It took the entire semester. It was not exactly easy to spend hours and hours and hours surrounded by chunks of skeleton, but the utterly functional, abstract beauty of the bones was mesmerizing and meditative. The environment that Wesley provided, the encouragement of their staff, and the questions of the seminarians made the process tolerable and even joyful. And of course, it made me contemplate the content ever more deeply. Somehow the irony of the fact that the original drawing will completely disappear (as I cut the block) was equally delightful to me.

In what ways has your block-cutting changed since Prima Veritas in 2000? What are you trying to achieve in your cutting now that you weren’t able to do back then? How does your line try to reflect the structure of the bones?

Prima Veritas was only the fourth woodcut I’d ever done, and I’d never carved skeletons–let alone draw them that intently–so the whole thing was an enormous, terrifying, thrilling, nerve-wracking process. And while charcoal drawing lets you know where all those various shades of gray will be and you have the luxury of an eraser, woodcut only allows you the ON or OFF switch of black and white. So making “gray” is about shape and direction and size and density of carved marks. It’s all about problem-solving along the way: analyzing, carving and creating light out of the ‘black’ of the wood.

Now that I have more experience with carving and have the proper tools, I do anticipate and cut in the direction of the charcoal marks more deliberately, but the last thing I want to do is have the carving process become routine. There still has to be some discovery and magic in the moment when the gouge passes through the wood.

It’s akin to painting in watercolor, where you have to reserve the white of the paper. In woodcut you have to hold the black of the wood sacred. There are no “do-overs.” Once the wood is gone, it’s gone. Making succinct, descriptive, yet intriguing cuts is paramount. Carving is drawing with light: caressing contours, revealing volumes across masses, describing textures, whispering in shadows. But because of the grain and its natural quirks, the wood is always in charge, so it keeps you humble. And if you do slip up, you’ve got to make lemonade. So, patience … breathing … focus … walking away …. letting go. Rushing is not an option.

How do you go about checking on the progress of your cutting? What do you cut first and why?

Just as I used a mirror to check for accuracy while I was drawing, I constantly do rubbings throughout the carving process. During each session I focus on a specific passage, or bone, or joint. As I cut a specific area, I’ll lay down a piece of thin tracing paper and rub the surface with a soft woodless graphite stick. This reveals what is in the surface of the wood, and lets me decide what more needs to be removed. Because it’s translucent, I can hold the tracing paper up to a window and view it from behind to see how the finished print might appear.

I won’t know what the entire image will look like until I’ve inked it up and printed a proof. But I try to have things nearly completely carved before I proof the plate because the wood feels entirely different once it’s been inked (much more unpleasant to carve). More importantly, if I proof the whole block, the rest of the original drawing will be completely lost.

Carving sessions are determined by whether I’m working dark to light or light to dark in any given area. Essentially, the image, the wood, and I are in a constant dialogue. What needs to be in front of what? How to accomplish that? It’s one huge entrancing, baffling, aggravating, addictive puzzle. Sometimes I’ll focus on a small, fussy passage first, since that determines a focal point and I need to know what the wood has decided it will look like before I move on to let in a larger, simpler area of light. Other times, it’s about finding just the tiniest whispers of form lurking in the shadows.

The final print will be such a surprise to me. There’s a huge gap between impulse and final image. It’s some seriously delayed gratification! (I know that Prima Veritas took me 192 hours to carve. I clock in and out on my wood block. It’s actually a diary of sorts.)

What’s your target date for finishing this print?

The simple answer is before I turn 54.

My goal is to have The Exposure of Luxury block fully carved and printed in time for my solo show, Beneath the Old Masters: Evolution and Process, this December at Washington Printmakers Gallery in Washington, DC. This is the first time all of the skeletal woodcuts will have been shown together. I plan on showing at least one of the finished woodcut plates and the drawing I’m currently doing on wood of another skeletal image (Mantegna’s Dead Christ) that I tentatively began in 2004. Dead Bob will make an appearance; so will my tools and a basket filled with 13 years’ worth of rubbings, with a little personal commentary about this long voyage.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/down-to-the-bone/trackback/

Pingback: New shows added! | DCimPRINT