Bruno Goldschmitt’s “Die Bibel”

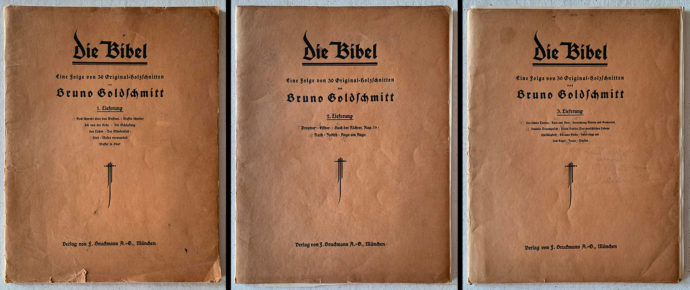

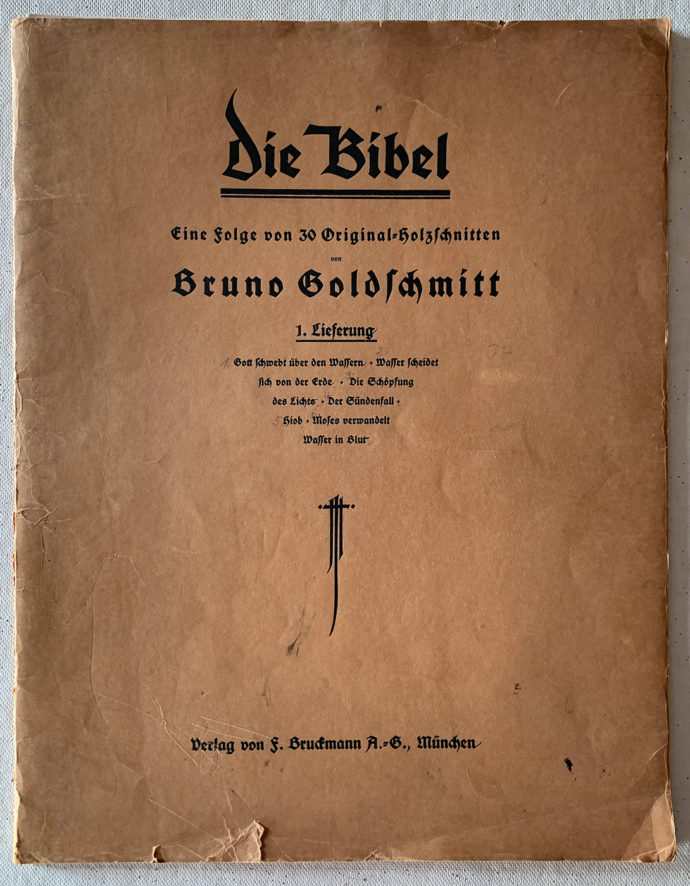

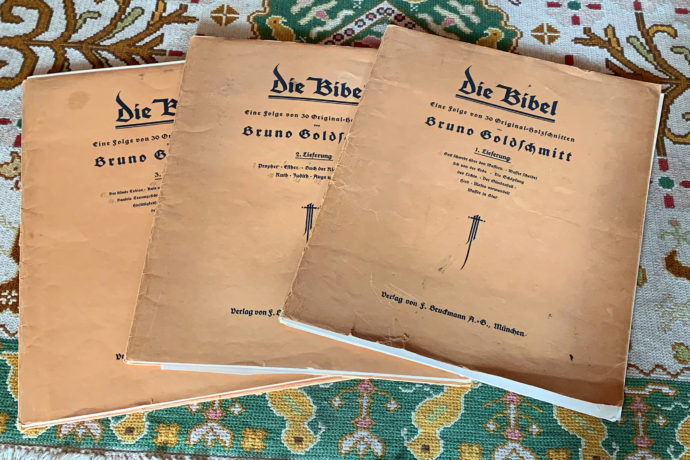

Three “Lieserung” (folders) comprise Bruno Goldschmitt’s “Die Bibel.” Each measures 25 1/8″ x 19 3/4″ (63.8 cm x 52 cm)

Introduction

For a blogger who has devoted considerable effort to present Jewish artists and Holocaust-related printmaking efforts, namely by Erich Glas, P.K. Hoenich and Arieh Allweil (see links for Glas, Hoenich and Allweil), it may surprise some that this post is devoted to a member of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. But well before the Nazi era Bruno Goldschmitt (1881-1964) produced Die Bibel, a remarkable series of wood engravings on the Old Testatment.

In this lithograph Goldschmitt metaphorically surrounds a mighty Germany with animal images of weaker neighbors.

Well before Hitler, Goldschmitt graphically presented himself as an ardent German. The Library of Congress website has the following commentary on this Goldschmitt lithograph: “Print depicting the state of German affairs following August 1, 1914 (the date it entered the first World War), showing a gigantic male figure, representing Germany, wearing armor and holding a sword, with rows of well disciplined soldiers marching below toward the ruins of a building spewing smoke on the left. Flanking the upper half of the giant figure are a Russian bear with its mouth open in agony and mid-riff bones exposed, an aged, toothless and hairless British lion with a monkey, representing Japan, sitting in the loop of its tail, and on the left, a frightened Gallic cock representing France.”

A range of dates are given for the production of Die Bibel. The Achenbach Foundation of the Fine Arts Museums of San Fransisco displays online all the plates of Die Bibel and lists the date as “ca. 1910-20.” Herbert Furst in his 1924 book The Modern Woodcut (John Lane The Bodley Head limited, London) illustrates two plates from Die Bidel. My three folders are not dated.

According to a very brief Wikipedia listing Goldschmitt joined the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (the Nazi Party) in 1932.

“In the study Die Tapisserie im National Socialism by Anja Prölß-Kammerer from the year 2000 Goldschmitt is described as a zealous party member. In a letter from 1935 to the board of the ‘Deutsche Kunstgesellschaft,’ he wrote about Jews and communists that they were ‘an imported rotten sponge’ that had to be removed from the art.”

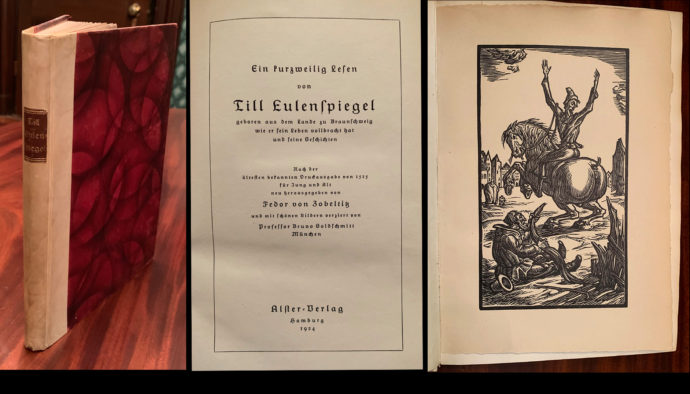

Goldschmitt illustrated this 1924 book on “Till Eulenspiegel” with woodcuts in a pseudo-16th-century style.

Goldschmitt was a prolific book illustrator. I’ve had this copy of Till Eulenspiegel for decades. His woodcuts printed on fine paperwork were inserted amid the text. The same publisher Alster-Verlap issued William Tell with Goldschmitt woodcuts. He also illustrated Die Schriften Salomos (The Writings of Solomon) 1922, Die Offenbarung Sankt Johannis (The Revelation of Saint John) 1923, and Zwölf Fastnachtspiele (Twelve Carnival Games) 1922.

What attracted me to his Die Bibel was the Old Testament topic, which also fascinated a Jewish German artist Gustav Wolf. Despite having three portfolios of his work I’ve yet to blog on Wolf (1887-1947), who escaped Germany in 1938 and settled in the U.S.

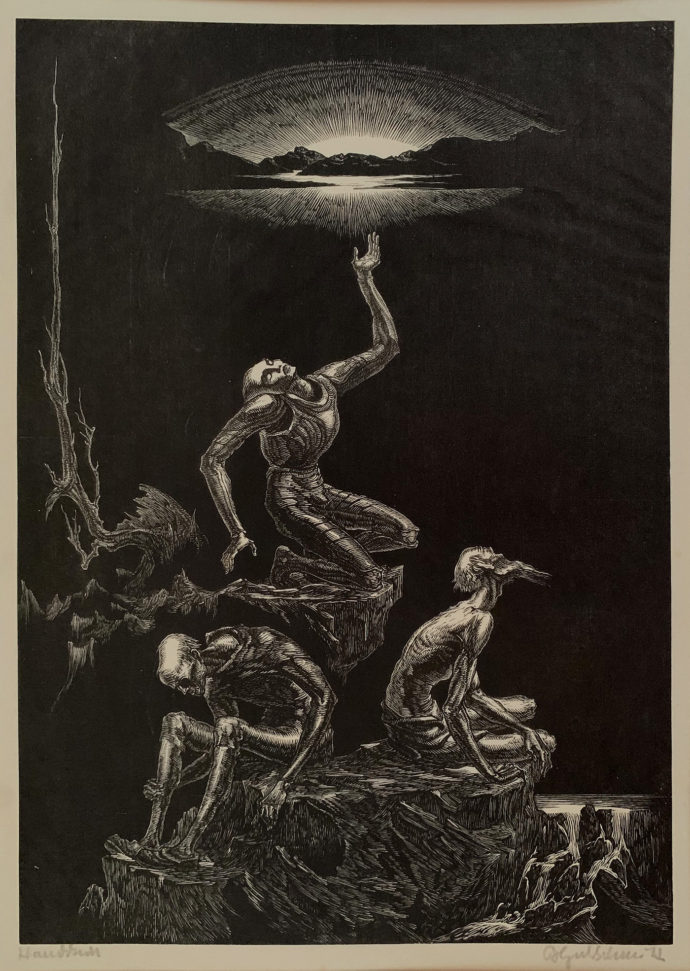

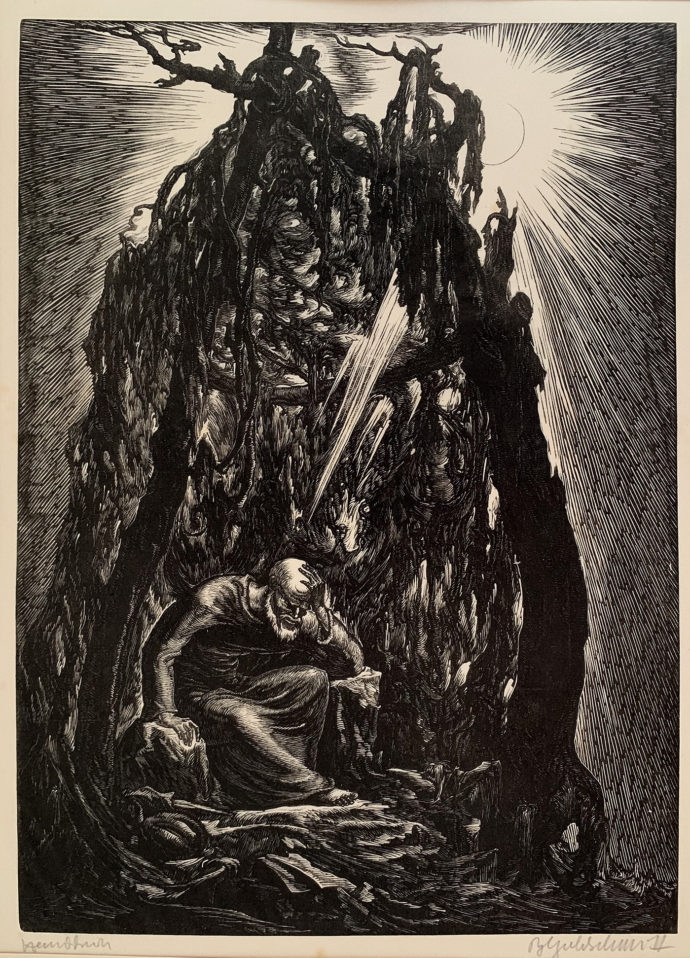

(Left) “The Creation of Light,” the third plate in the first folder of Goldschmitt’s “Die Bibel,” and (Right) “Lord, thou hast been our dwelling place in all generations,” the seventh plate in Wolf’s 1947 “Twelve Wood Engravings to the Psalms”

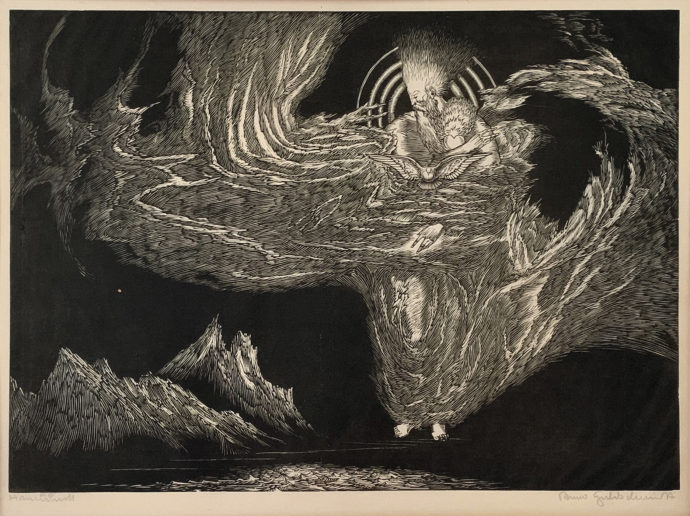

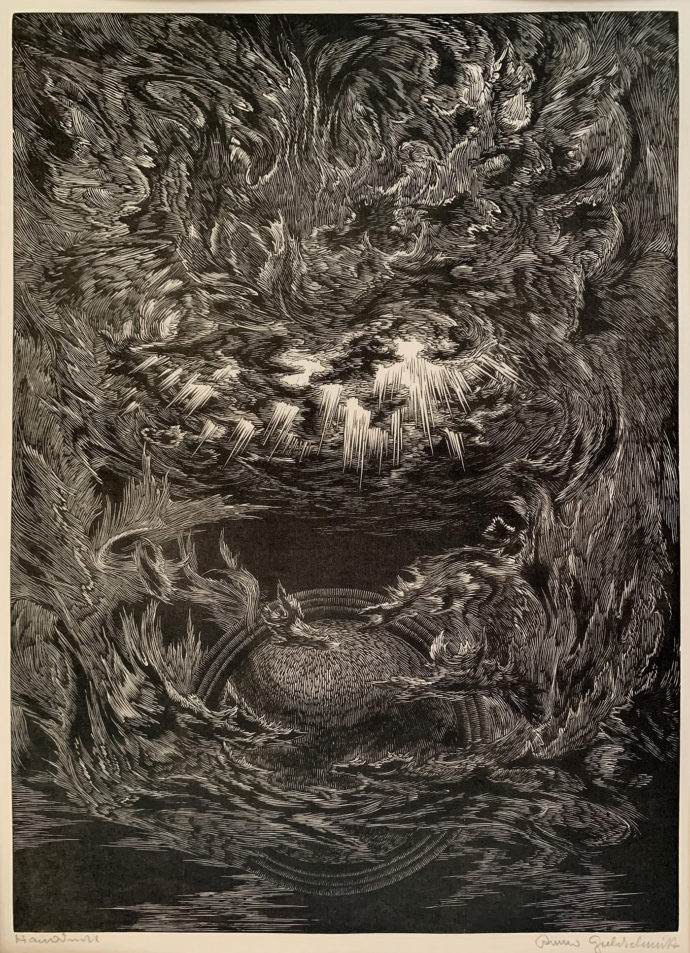

I’ve chosen these images by Goldschmitt (left) and Wolf (right) because they share the artists’ wonder about the Earth’s creation and because they evidently share the same medium on an unusually large scale: wood engraving. The Wolf title–Twelve Wood Engravings to the Psalms–clearly declares its medium as wood engraving, a relief printing technique involving the cutting into engrain blocks of wood. As in the Wolf print the image in a wood engraving is often executed in white lines. If you look back to Goldschmitt’s woodcut in Till Eulenspiegel, you’ll see the image is created in black lines.

I bring this distinction up because Die Bibel was presented as a work in woodcuts, not wood engravings. The Die Bibel folders stated under the title that contents were “Original-holzschnitten”–original woodcuts. But the image creation in Goldschmitt’s plate is extremely similar to Wolf’s. Both used the white-line technique with a similar degree of detail. (The plates are close in size. The Goldschmitt is 16 1/4″ x 11 3/4″ or 41.6 cm x 30 cm. The Wolf is 14 1/8″ x 11 1/8” or 36 cm x 28.3 cm.) The Germans didn’t see the need to distinguish between woodcuts and wood engravings. Even the extremely delicate wood engravings in Erich Glas’s c. 1920 portfolio of eight prints on Aesopische Fabeln (Aesop’s Fables) were presented as holzschnitte. (See my post on Glas’s fables.)

Edition issues

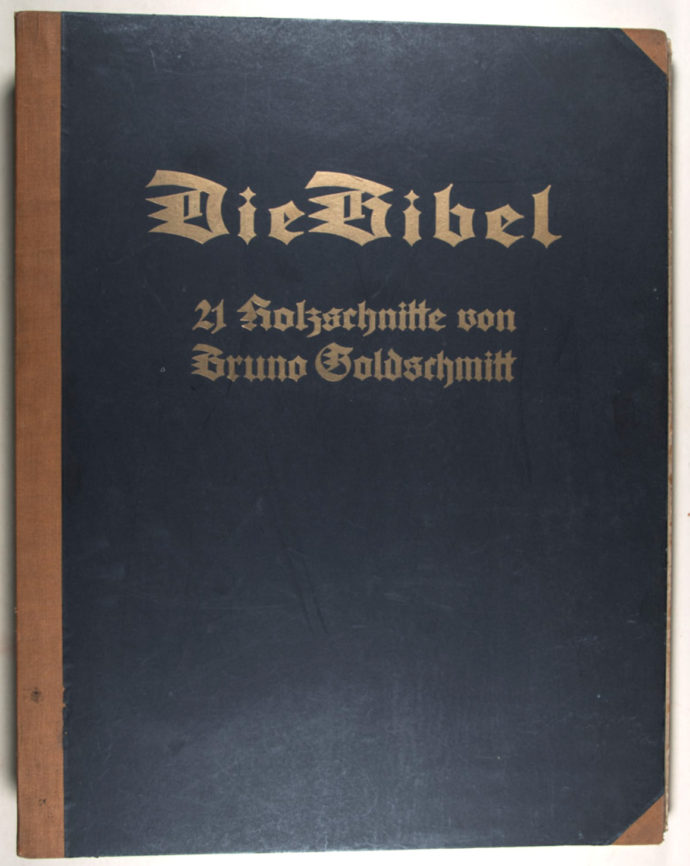

I purchased my copy of Die Bibel via an auction held in June 2021 online by Galerie Gerda Bassenge in Berlin. It carried the following description translated from the German: “The Bible: Folders 1-3. 21 woodcuts on Japan, loose sheets in original mats (chipped, small blemishes, slightly stained, pencil annotations), published by F. Bruckmann, Munich, edition II, hand prints on imperial Japan, around 1925 Folio. All by hand inscribed ‘Handstruck’ and signed ‘Bruno Goldschmitt.’ ” The beginning price as 500 euros.

As soon as I saw the listing, I consulted AbeBooks.com and came upon two listings: one by Eric Chaim Kline, Bookseller in Santa Monica, CA, U.S.A. and one by Hübner Einzelunternehmen in Hamburg, Germany.

The Eric Kline Bookseller listing read: “Hardcover. Condition: g to vg. Limited edition. 1/45. Large atlas folio. Unpaginated. [21] loose plates, as issued. Original 3/4 cloth portfolio over paper covered boards, with gold lettering on front cover. This most impressive work is a compilation of 21 striking woodcuts by Bruno Goldschmitt, depicting scenes from the Old Testament. Each matted woodcut is protected with a tissue-guard and is signed by the artist. One of 45 copies of the Ausgabe II, with woodcuts on Imperial Japan, of which this is No. 33. (Ausgabe is German for “edition.”) The price was $2,500.

The Hamburg seller’s listing simply said: “Die Bibel : 21 woodcuts. Edition III, 300 examples” and “21 sheets in folder, folio 20 woodcuts, each hand-signed by the artist B. Goldschmitt.” Price about $910.

Well, the folders that were offered at auction as the second edition certainly didn’t look like the cover for the second edition of Die Bibel as offered by Eric Kline Bookseller.

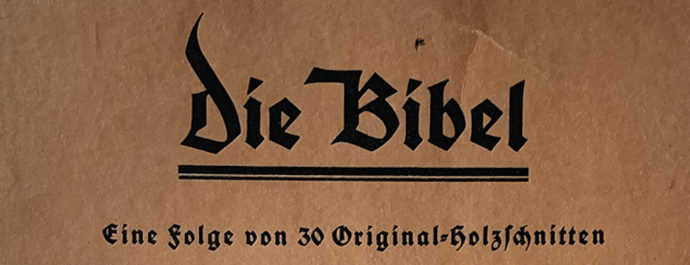

But by far the biggest discrepancy was the number of the plates. Each folder reads: “A sequence of 30 original woodcuts.” In fact I didn’t key in on that fact until my copy arrived. (No one bid against me. So I got the item for 630 euros–500 plus 130 buyer’s premium.)

The first folder shows titles for 6 plates. (A previous owner made pencil notations numbering the plates.) The second folder shows titles for 6 more plates. And the third folder lists 9 more plates. The total, as the auctioneer promised, was 21 plates. No other text came with the folders. And 21 is the number for each of the offerings in AbeBooks.com. So what happened? Was there ever a fourth folder with 9 more plates to make a total of 30? And if there were 9 more plates, why weren’t they included in other editions? Furthermore, what edition do I have?

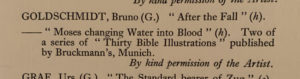

I credit Herbert Furst with answering the last question. His book The Modern Woodcut was published 1924. To the right is an image from his “List of Illustrations.” It named the Goldschmitt images that he used in his book “By kind permission of the Artist” and stated that those two are “of a series of ‘Thirty Bible Illustrations’ published by Bruckmann’s, Munich.”

So clearly before the Furst book was published and before the edition offered by Eric Kline Bookseller, Goldschmitt’s Die Bibel project was intended to have 30 prints as my folders state. But subsequent editions only had 21 prints, the same number contained in the three folders that I have. I have to assume that the fourth folder with the last intended 9 prints were never published.

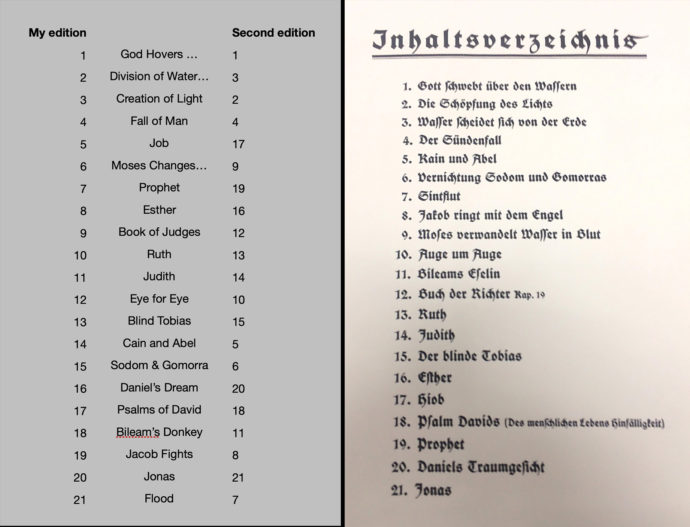

I reached out to Eric Kline Bookseller and asked if its edition had any text pages. Jürgen Schacht emailed back saying: “The text part contains four pages with title page, colophon, a blank page and the table of content with titles of twenty-one prints. That seems to be all that was published.” As to his knowledge of the editions of Die Bibel, he wrote: “The Edition A contains five hand-colored prints, our edition [B] 45 [copies] on Japan paper and Edition C 300 [copies] prints on handmade paper.” He did me the great favor of sending an image of the index for his second edition.

A comparison of the sequence of plates in “Die Bibel” between my three folders and the second edition with the index from the second edition to the right.

The sequence of the wood engravings in my edition is based on the order of the titles listed on the outside of the folders. Plates 1-6 appeared on the first folder. Plates 7-12 on the second folder. And plates 13-21 on the third folder. When the later editions came out, the sequence was radically changed–particularly after the fourth plate–to better coordinate with the Old Testament.

So what do my three folders represent? Perhaps they were issued as part of a subscription, a common practice in the 19th century. Dickens novels were issued that way. The books Gustave Doré illustrated were also issued by subscription. (I once had all the parts to his Divine Comedy. Don’t ask my why I sold them.) Once the subscription was complete, the subscriber had the option of having all the parts bound into a book.

Maybe what I have represented the working sequence of Goldschmitt’s Bible project that was never completed as planned. Or as Jürgen Schacht emailed: “Obviously the publisher made an adjustment when it became clear that nine of the announced 30 prints weren’t going to be published.”

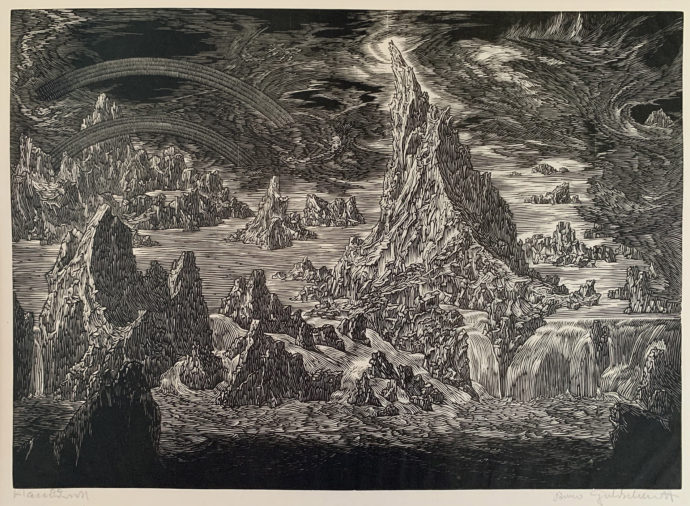

Regardless, each of the wood engravings in my copy of Die Bibel are printed on fine paper, perhaps the Imperial Japan that was used for the second edition. And like that edition, each print was matted and signed in pencil on the lower right and annotated on the lower left with the word “Handruckt,” for printed by hand.

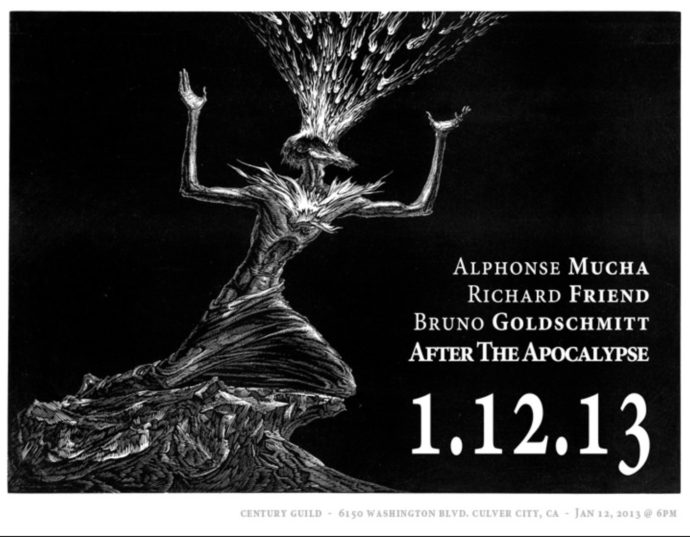

Bruno Goldschmitt’s wood engraving “Prophet” was used for a poster for a Century Guild exhibition in Culver City, CA.

Die Bibel

I’ve found little about Bruno Goldschmitt online. Beside the Wikipedia listing, his work was briefly discussed on the Century Guild website as part of a notification of an exhibition starting 13 Jan. 2013. LINK Here’s the one paragraph there on Goldschmitt:

Bruno Goldschmitt was a German Expressionist, who although somewhat obscure today, is probably best known for his printmaking using woodcuts, although he also made tapestries, paintings, and worked in various other mediums. A friend and associate of Nobel winning German-Swiss poet, novelist, and painter Herman Hesse, Goldschmitt was very much of the contemporary school of art stylistically and he incorporated a great number of influences into his aesthetic. His work is imbued with much of the iconography of Symbolism and the emotional potency of Expressionism, as well as the bold line work and sharp, exaggerated angles of the latter. But in terms of the themes he expressed, most can be traced back to Germany’s ancient history and medieval European art in general. Allegorical woodcuts and drawings of classical figures of European myth and legend abound in his work, as do idyllic and somewhat pantheistic scenes of rural countryside activities and seasonal changes, but most fascinating are his dynamic images inspired by the Old Testament.

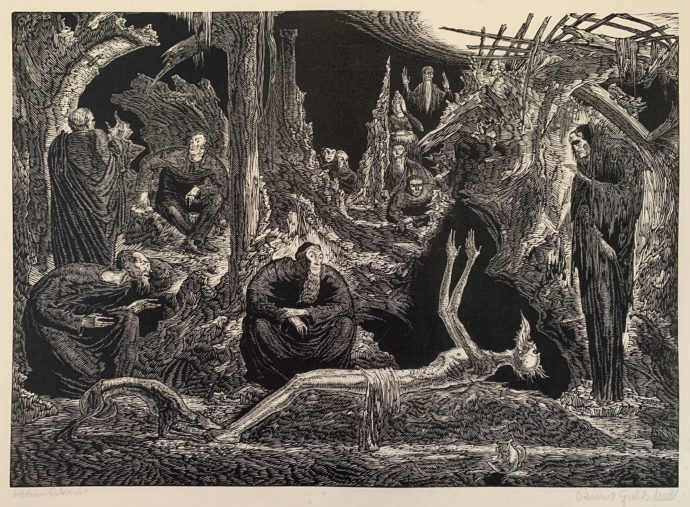

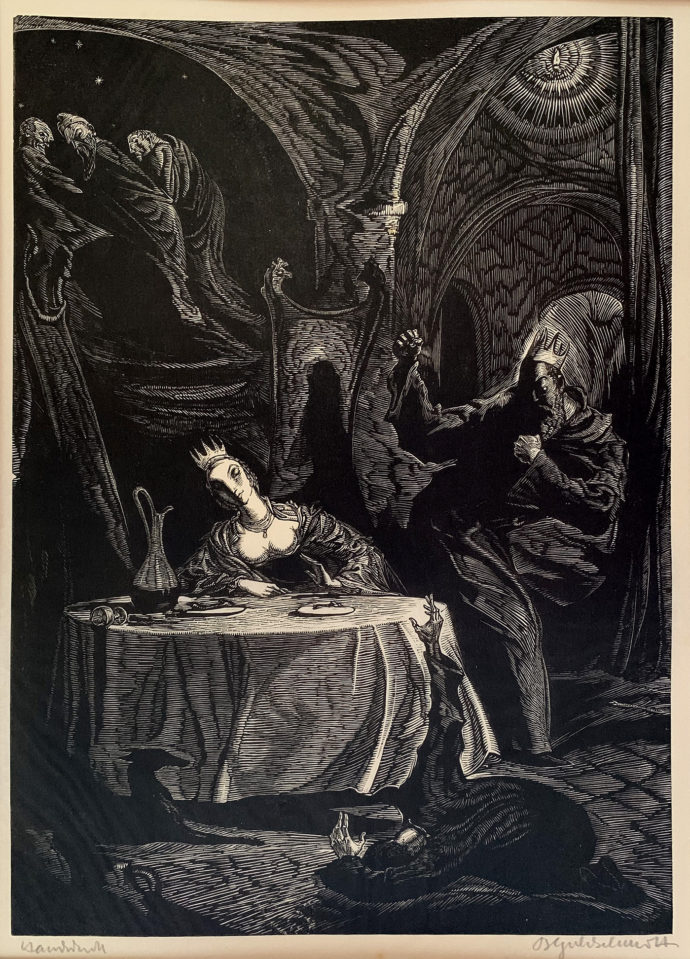

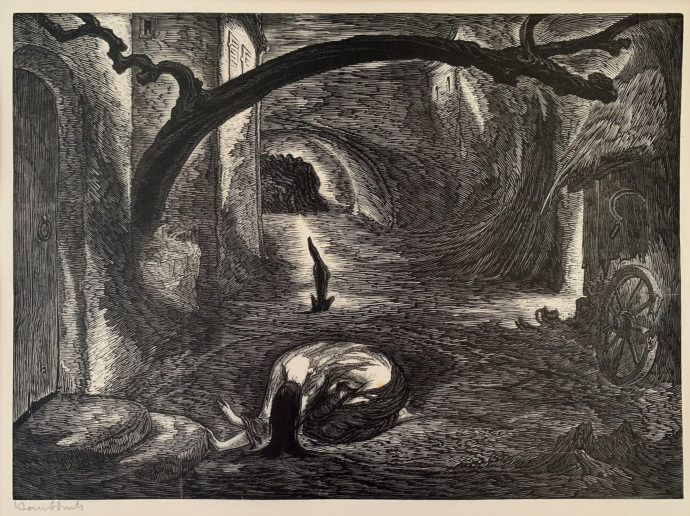

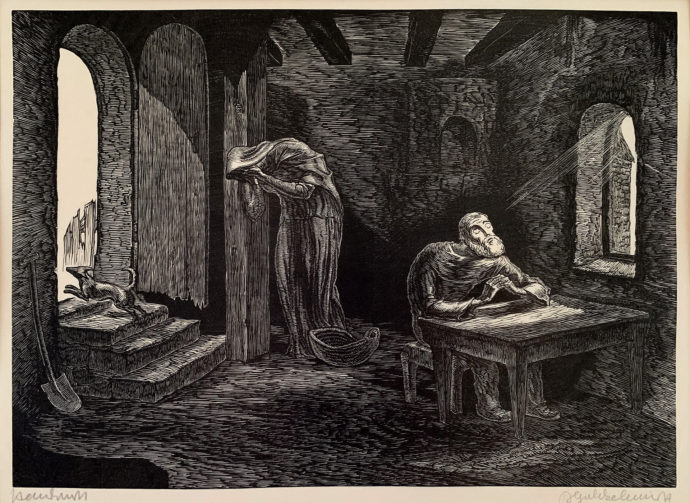

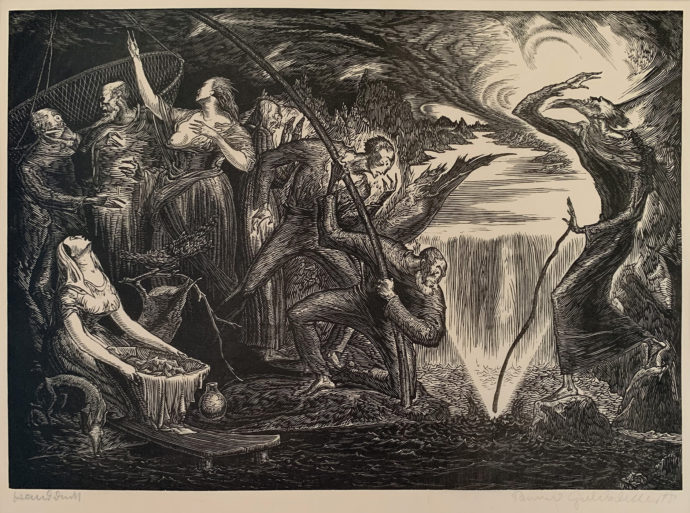

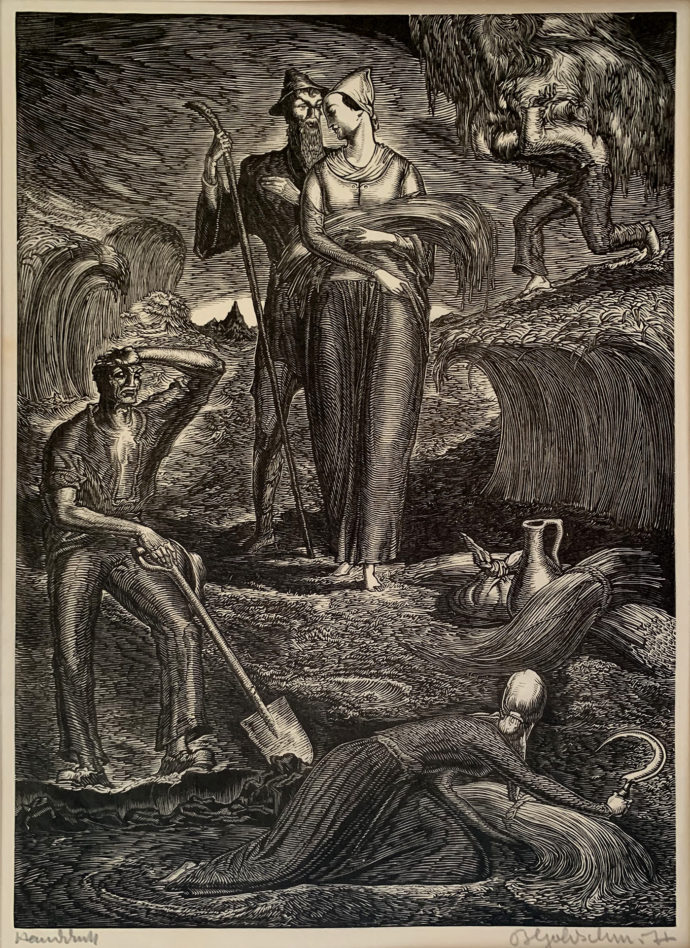

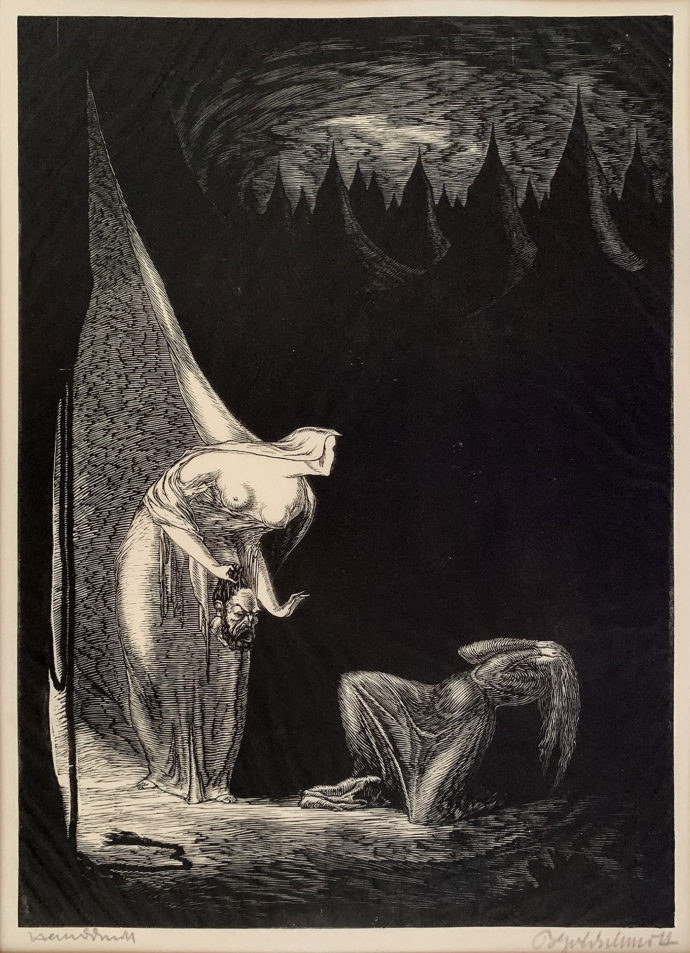

With that, here is my copy of Die Bibel, showing in sequence each folder followed by the prints as listed on each folder.

God Hovers Above the Waters

The Division of Water and Earth

The Creation of Light

The Fall

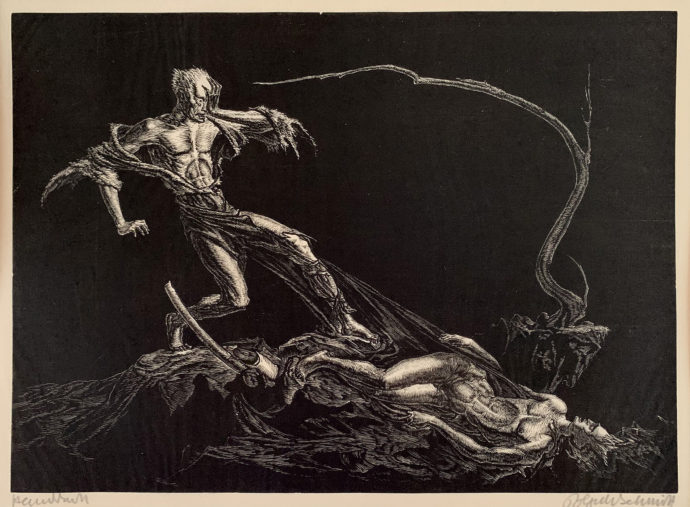

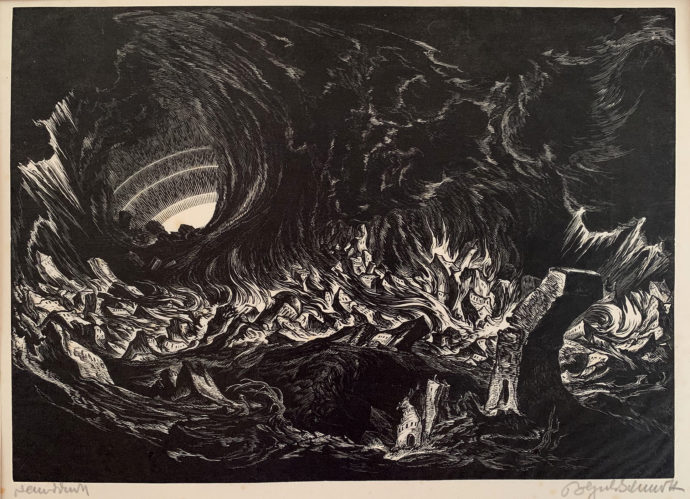

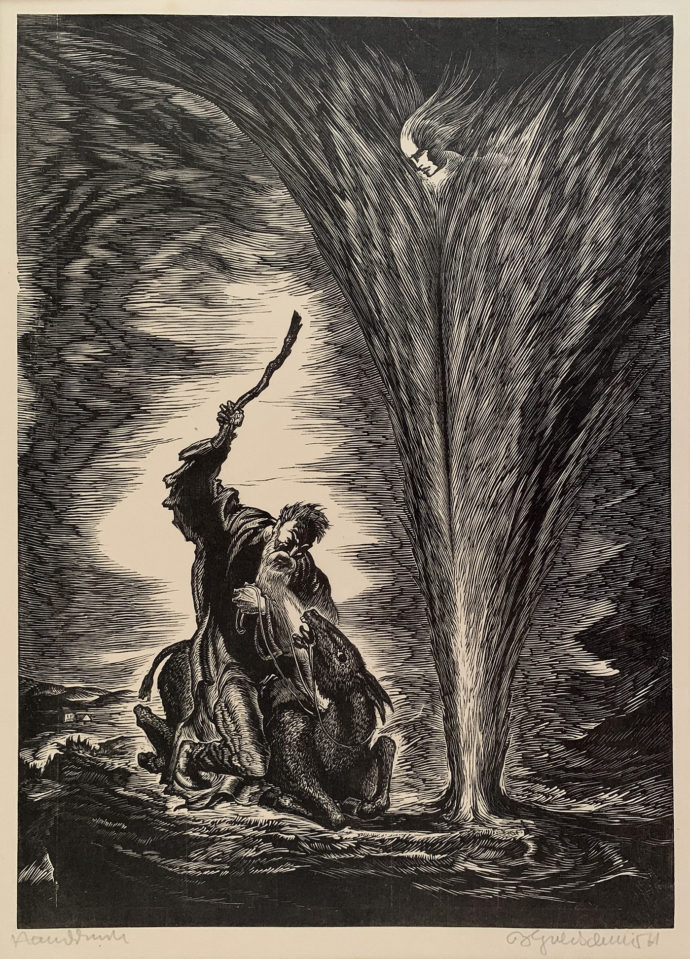

Job

Moses Changes Water into Blood

Prophet

Esther

Book of Judges, Chapter 9

Ruth

Judith

An Eye For an Eye

The Blind Tobias

Cain and Abel

Destruction of Sodom and Gomorra

Daniel’s Dream

the frailty of human life (Psalm of David)

Bileam’s Donkey

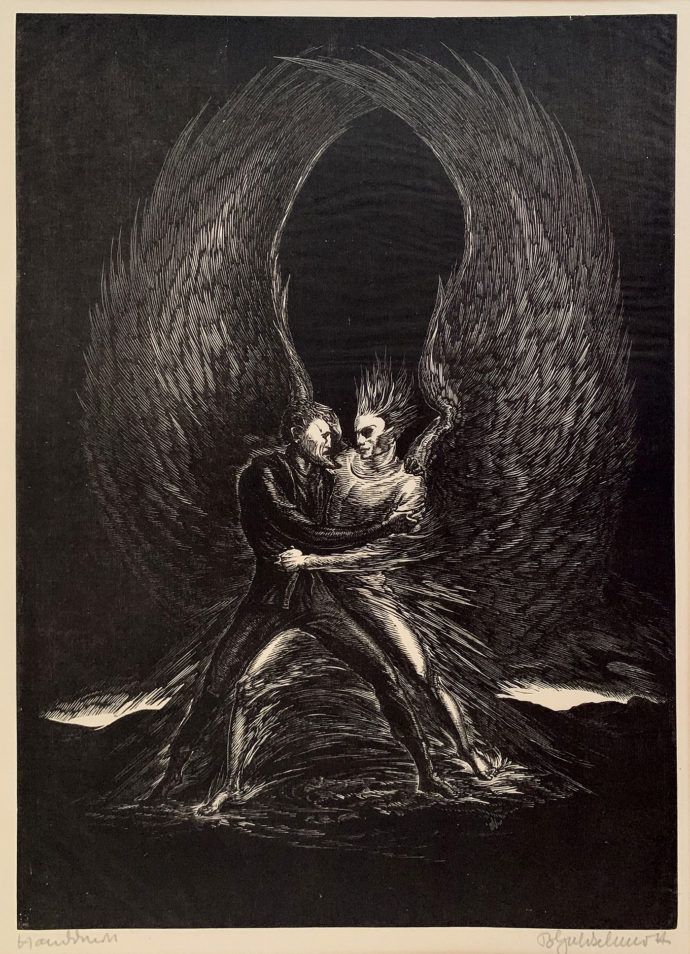

Jacob Fights with the Angel

Jonas

Flood

Endnote

Your comments are most welcome. Please send them to me at p1m1@comcast.net and I’ll append them here.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/bruno-goldschmitts-die-bibel/trackback/