Belgium and the Netherlands: The Paper Trail

Introduction

If you spend four weeks in Belgium and the Netherlandsas as I did this past spring, you are bound to be showered with great paintings by the likes of Jan van Eyck, Pieter Breugel the Elder and the Younger, Peter Paul Rubens, Frans Hals, great Dutch marine and still life painters, Rembrandt van Rijn, Vincent van Gogh. and Piet Mondrian. I certainly was. But as a collector of works on paper–namely prints and books with prints–coming across exhibitions of works on paper was particularly satisfying. Sometimes prints appeared where I expected them to be, like at the Rembrandthuis in Amsterdam. Sometimes I came upon them by surprise, like prints by the British artist Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956) at the Arendhuis in Brugge (Bruges), Belgium, and by prints by the Swiss artist Félix Vallotton (1865-1925) at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. My very first surprise came during my first day in Antwerpen, Belgium.

Plantin-Moretus Museum

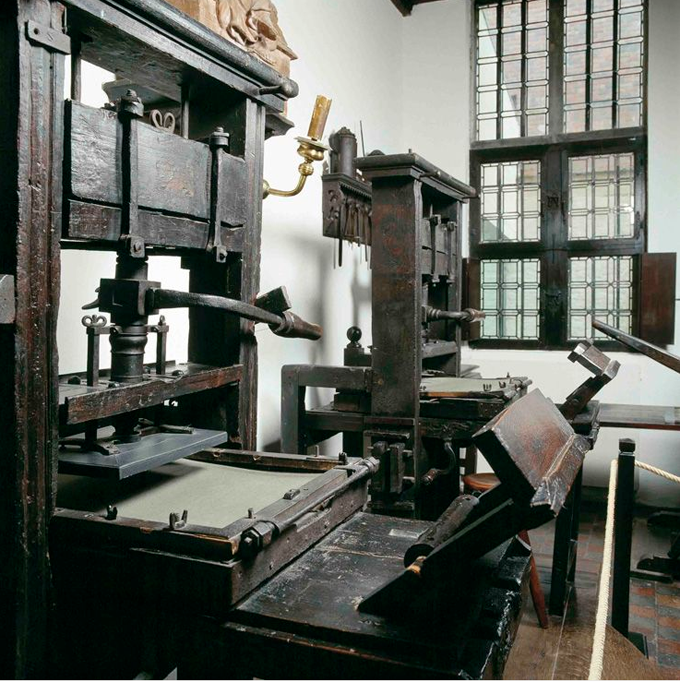

If you’re a book lover, this place is the Holy Grael. It earns its place as a UNESCO World Heritage site. From the UNESCO website, the museum is described as “a printing plant and publishing house dating from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Situated in Antwerp, one of the three leading cities of early European printing along with Paris and Venice, it is associated with the history of the invention and spread of typography. Its name refers to the greatest printer-publisher of the second half of the 16th century: Christophe Plantin (c. 1520–89). The monument is of outstanding architectural value. It contains exhaustive evidence of the life and work of what was the most prolific printing and publishing house in Europe in the late 16th century. … On the death of Plantin in 1589, his son-in-law Jan Moretus I (1543-1610) took over at the head of the best equipped company in Europe, and it was thanks to the Moretus family that the continuity of the production activities of the firm was maintained until 1867.”

Photo top: off http://www.visitflanders.us. Photos below: off the blog UCL Centre for publishing.

Photo top: off http://www.visitflanders.us. Photos below: off the blog UCL Centre for publishing.

It’s the continuity that’s staggering: 300 years of printing in the same place. Ergo, not only do you see the oldest surviving movable-type press (above), but you see displays of cast-lead fonts, font-making tools, beautiful hand-colored atlases, original copper engraved plates or woodcut blocks and modern impressions from them (see above), the 16-century living quarters with amazing embossed Spanish leather wallcoverings, and libraries holding the products of this illustrious publishing dynasty.

The museum’s website is: http://www.museumplantinmoretus.be/Museum_PlantinMoretus_EN The UNESCO website provides a good deal more information on the museum, detailing the justifications for its listing as a World Heritage site: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1185

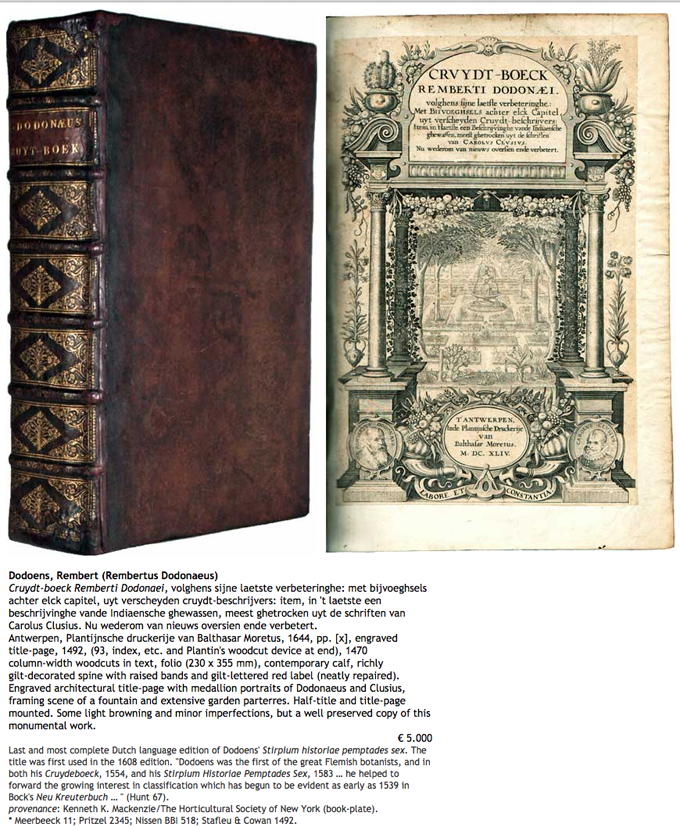

For Sale: A 1644 botanical book printed in Antwerpen by Balthasar Moretus is offered for sale by antiquariaat Jan Meemelink, in Den Haag Netherlands. See: http://www.meemelink.com/books_pages/25896.Dodoens.htm

Let me throw in one photo (taken by my sister Susan Boyer) from the Rubenshuis, also in Antwerpen. While quite spectacular in its own right, it was not a venue for works on papers even though a number of printmakers made wonderful engravings based on Rubens paintings. These two prints (reproductions, I suspect) in the photo show how the house looked in late in the 17th century. (Rubens died in 1640). But I’m including this image because it also offers a peak at the 17th-century embossed leather wall-covering that I was much smitten by.

Passions of Christ, Brugge

Stradanus

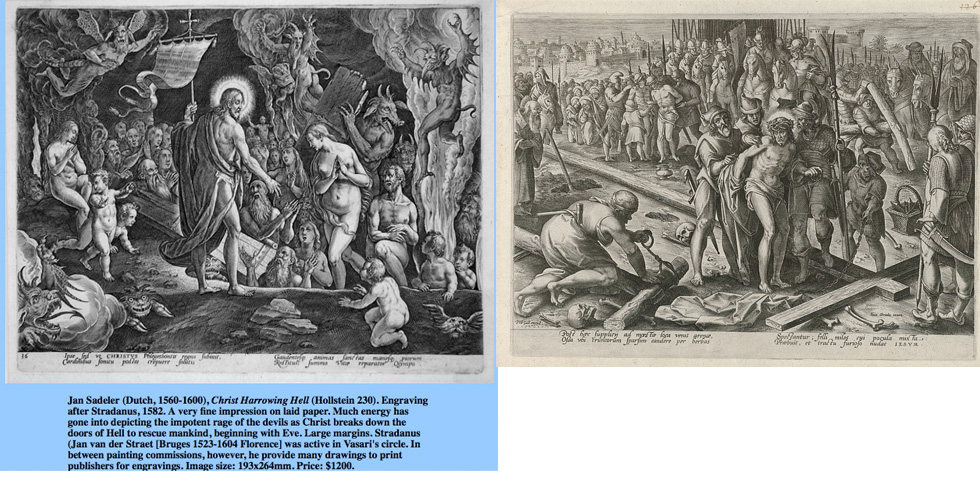

Two museums in Brugge (Bruges if you’re French) had nifty treats for the print fancier. A temporary exhibition in the Groeninge Museum featured the 36 engravings on the Passion of Christ based on drawings by the artist Stradanus. I was not astute enough to photograph any of them, and, when I decided to do this blog, I couldn’t quite remember the artist’s name. I didn’t find mention of it at the museums’ website. But I did find this posting from the Groeninge’s Facebook page:

Then via some web surfing I came up with this listing for a monograph on Stradanus: “Johannes Stradanus (Jan van der Straet, Giovanni Stradano) is one of the most well-known unknown artists in history. Even though the Bruges-born painter (1523-1605) had a more than successful career in the highly competitive city of Florence in the second half of the 16th century, his name long remained a well-hidden secret for specialists only. Many of his works, though, are very well known. Around 1570, Stradanus – who began as designer of tapestries and fresco painter in service of the Medici – started a second career as draughtsman and designer of hundreds of prints. These were engraved, published and distributed all over the then-known world by Antwerp publishers in huge numbers. It are these works – widely collected, copied and used – which secured Stradanus’s place in art history as an inventive and influential artist. Based on the first ever monographic exhibition on Stradanus in the Groeningemuseum in Bruges (2008-2009), this study aims to reassess the importance and versatility of the artist’s oeuvre.” Here’s a link to the publisher’s page: http://www.brepols.net/Pages/ShowProduct.aspx?prod_id=IS-9782503529967-1

The image on the left came from the website of the Spraightwood Galleries of Upton, MA. To see the listing on the gallery’s website, go to: http://spaightwoodgalleries.com/Pages/Bible_Crucifixion2.html

As you would expect, eBay offers alternatives for purchasing Stradenus prints (although not necessarily lifetime impressions): http://www.ebay.com/sch/sis.html?_kw=RELIGIOUS+PRINT+17th+C+JOHN+BAPTIST+GALLE+STRADANUS+%231 Buyer beware.

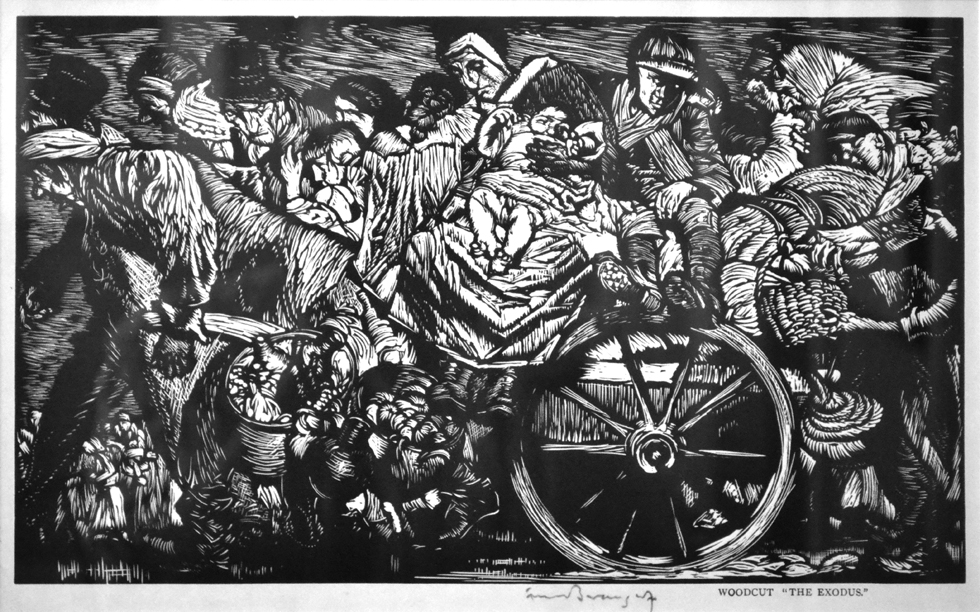

Brangwyn

The second Passion series came as a complete surprise at Arentshuis, across the alley from the Groeninge museum (and shared admission). Its second floor is devoted to the art of Brugge-born British artist Sir Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956). I was familiar with Brangwyn as a printmaker. His work appears in early 20th-century British books on woodcuts, like Herbert Furst’s The Modern Woodcut of 1924. I was lucky enough to purchase The Exodus, from Paul McCarron in 1987. The artist was evidently quite affected by the hardship and displacement of World War I when he made this image. I also knew that Brangwyn had collaborated with the Japanese artist Yoshijiro Urushibara (1888-1953). At the Annex Galleries website are several woodcuts from “a portfolio titled ‘Ten Woodcuts by Yoshijiro Urushibara’ done in 1924. … The woodcuts were cut and printed by Urushibara after watercolors by his friend and collaborator, British artist Frank Brangwyn.” To see a selection from this portfolio, go to: http://www.annexgalleries.com/inventory/artist/2410/Yoshijiro-Urushibara.html

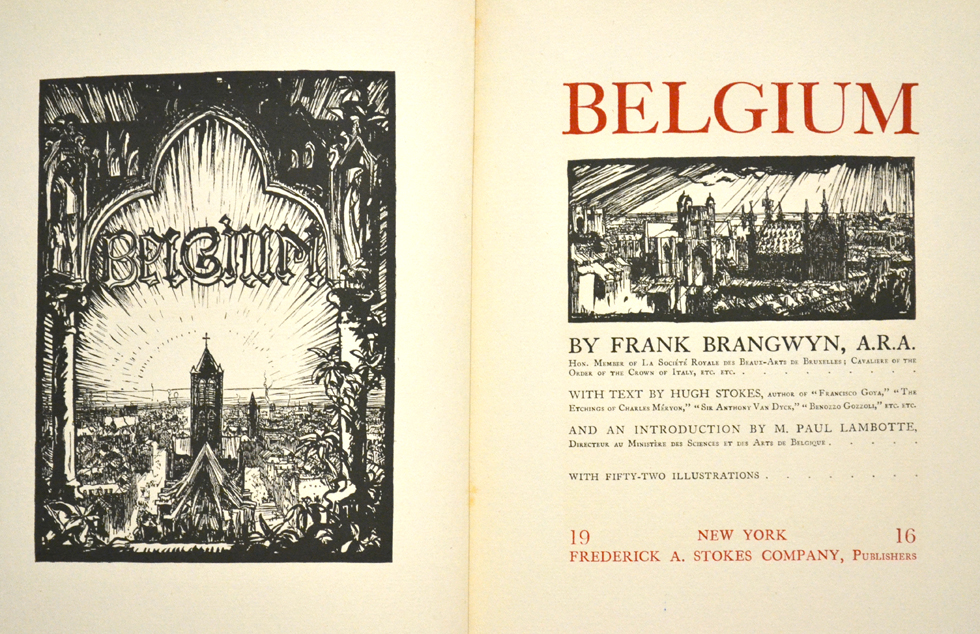

But so cursory was my knowledge of Brangwyn that I hadn’t known the affection he had for Belgium and what would motivate him in 1916 to produce a book of woodcuts of Belgium–a copy of which I had bought some 20 years ago. But what completely floored me was his Stations of the Cross series of large lithographs on display in a hallway. The website Sacred Art Pilgrim states: “The Stations of the Cross was a sacred theme of special importance to Brangwyn. As he told his artist-biographer, William de Belleroche, the subject was ‘at the back of my mind all of my life,’ and he hoped to make it his ‘most important work.’ Brangwyn was commissioned in 1920 to create a cycle of Stations of the Cross paintings for the war-damaged cathedral in Arras, France. The project was never completed, but Brangwyn made hundreds of studies and sketches. With the help of Belleroche, Brangwyn eventually produced a set of woodcuts on the theme between 1930 and 1934 and a lithographic series in 1935.” Further information on this series is at: http://www.frankbrangwyn.org/stations.html. Each image is approximately 30″ x 32″.

Vallotton at the Van Gogh

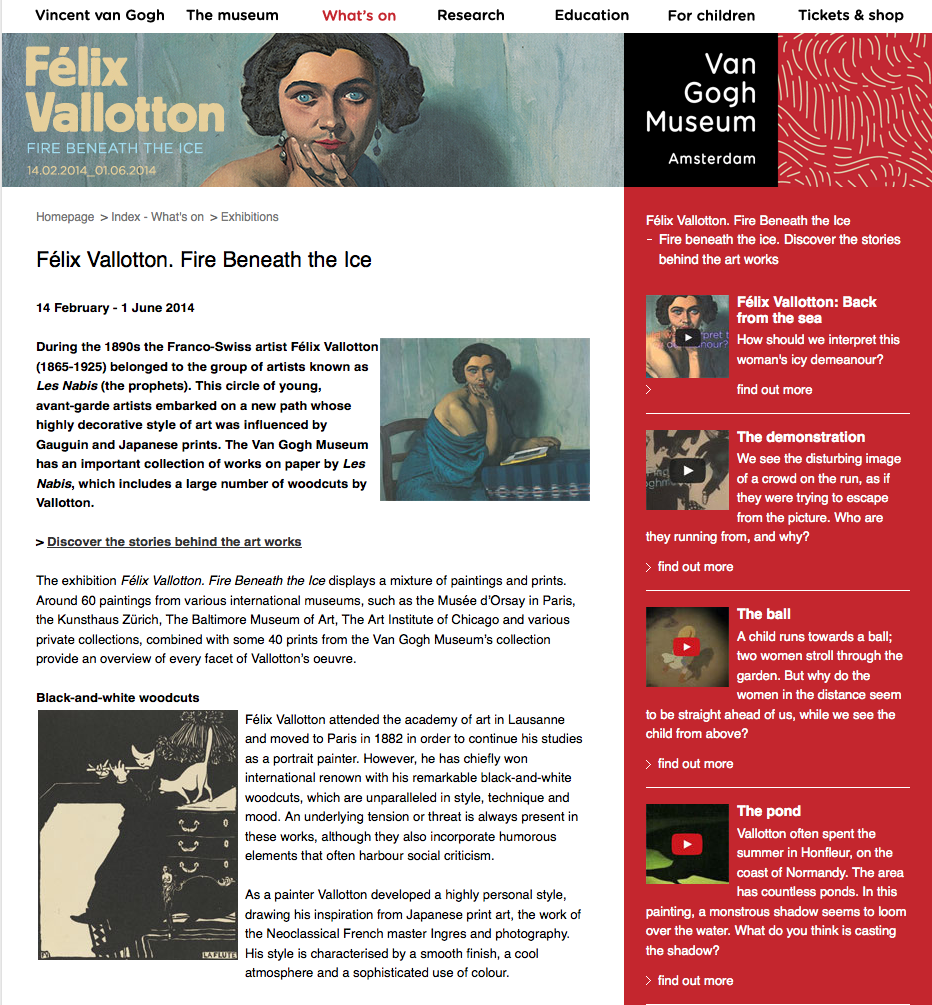

Thank goodness for the Netherdlands’ Museumkaart. The €54.95 cost paid for itself just by being able to stand in the much shorter line to enter Amsterdams’ Van Gogh Museum. (And at the neighboring Rijksmuseum, with the card we were ushered directly in–no line at all.) First off we did immerse ourselves in the short, turbulent and prolific life of Vincent van Gogh, but my heart was set on viewing the temporary exhibition of Felix Vallotton. His stark black-and-white woodcuts nearly make me swoon. Because the cost of owning any was always too dear for me, I’ve needed to get my Vallotton fix at museums. The display at the Van Gogh didn’t disappoint.

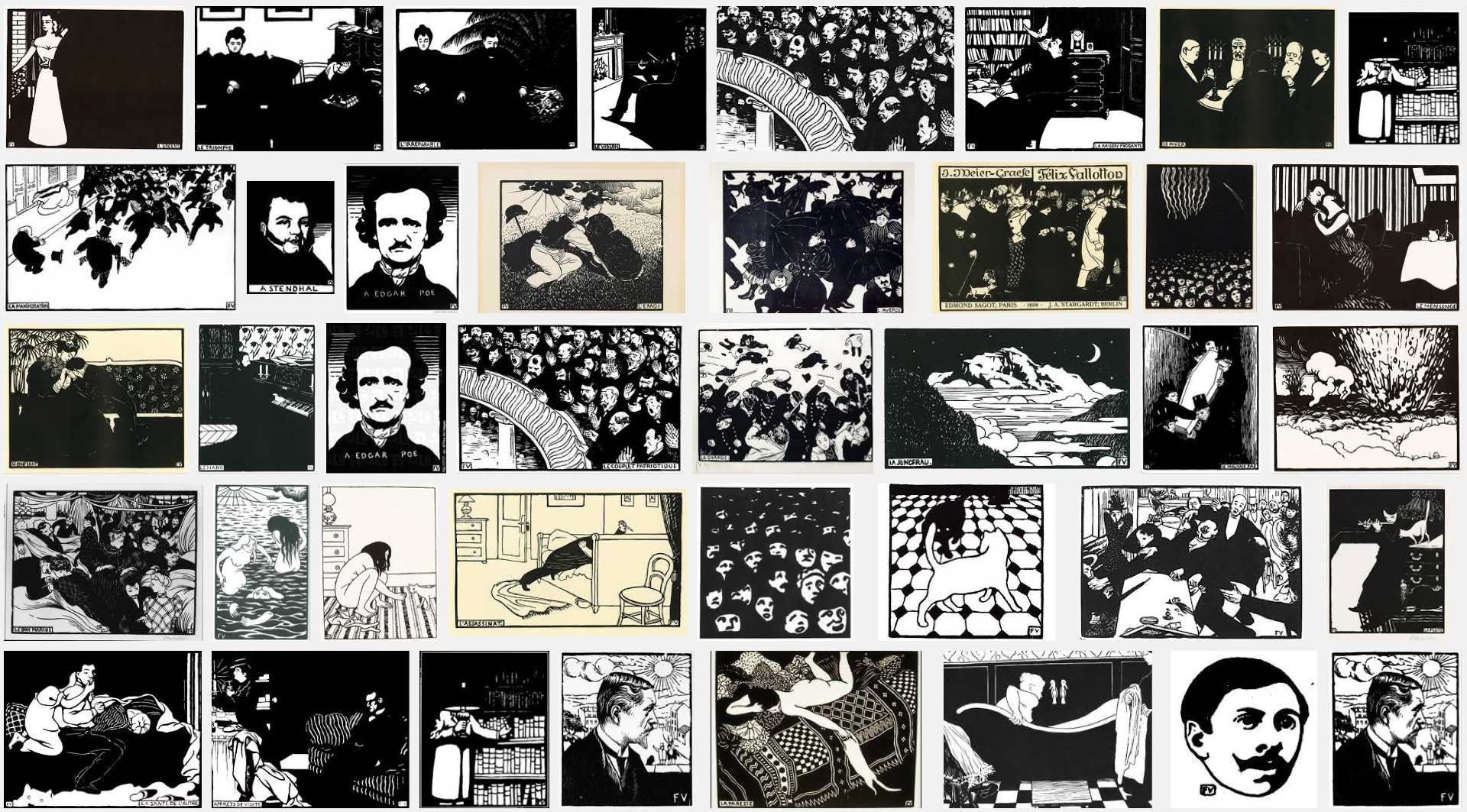

As this page from the Van Gogh Museum website states: “He has chiefly won international renown with his remarkable black-and-white woodcuts, which are unparalleled in style, technique and mood. An underlying tension or threat is always present in these works, although they also incorporate humorous elements that often harbour social criticism.” His dramatic use of black and white eliminated the subtleties of shading. Yet his visual essays on social tension couldn’t be more nuanced (or at times more explosive). Here’s a screen shot of visuals that resulted by searching for “Vallotton woodcuts.”

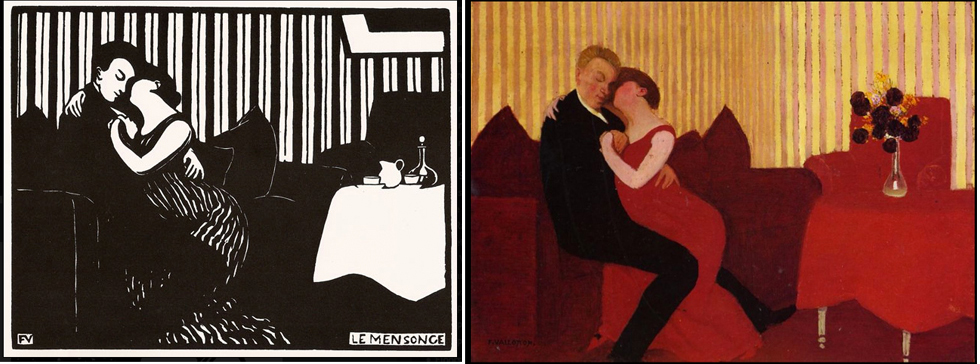

What was particularly nice about the exhibition is that it showed several complete series of Vallotton woodcuts. In fact another page from the museum’s website announces that it purchased one series– the ten-woodcuts Intimités (Intimacies)–as well as the single woodcut La Paresse (Laziness) during the run of the show. (See: http://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/vgm/index.jsp?page=350340&lang=en For a nice way to see closeups of this and another Vallotton series, go to the website of the Art Institute of Chicago: http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/artist/Vallotton%2C+Felix+Edouard

For friends of the Baltimore Museum of Art, one thing nice about the Intimités series is that encouraged the exhibition curators to borrow the painting The Lie (1897, 9 7/16″ x 13 1/8″, oil on artist board, The Cone Collection, formed by Dr. Caribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, Maryland). The Van Gogh also exhibited the striking Vallotton portrait of Gertrude Stein (also from the Cone collection).

– See more at: http://collection.artbma.org/emuseum/view/objects/asitem/search@/8/title-asc?t:state:flow=e84a611d-00fd-4915-b351-c7d824b9cece#sthash.tBamSamp.dpuf

– See more at: http://collection.artbma.org/emuseum/view/objects/asitem/search@/8/title-asc?t:state:flow=e84a611d-00fd-4915-b351-c7d824b9cece#sthash.tBamSamp.dpuf

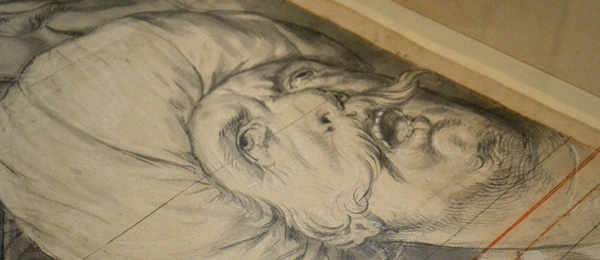

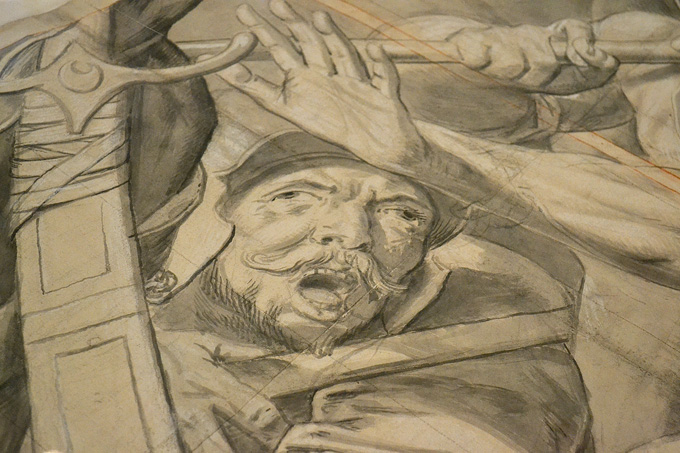

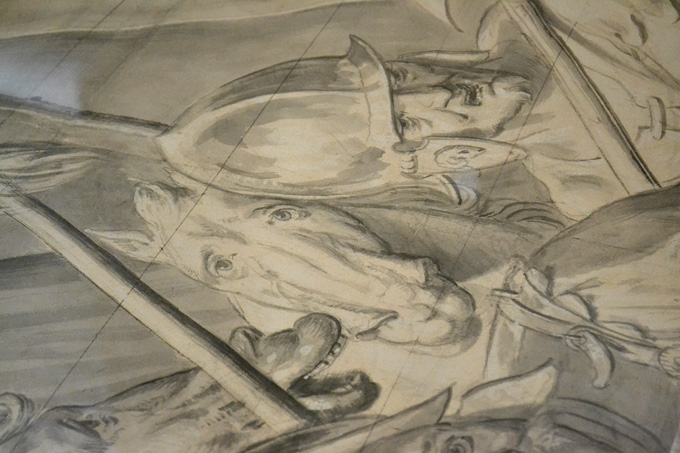

Cartoons in Gouda

Even if you’re not a cheese aficionado, the small city of Gouda has a real rarity for lovers of works on paper: the full-size cartoons for the famous set of the 16th-century stained-glass windows at Sint-Janiskerk. The earliest of the 72 windows were executed by the brothers Dirk and Wouter Crabeth between 1555 and 1571. They were of traditional Catholic imagery. Later windows (from 1594 to 1603) heed the post-Reformation call for secularist themes–such as the one below.

The windows themselves are stunningly beautiful. But as I said, the real treat for me wasn’t in the church but across the narrow lane and inside the Gouda Museum, housed in the Catherina Gasthuis, a hospice until 1910. Displayed were some of the drawn designs for those windows. Or as the website Vidimous–”the only on-line magazine devoted to medieval stained glass”–calls: “a unique collection as nowhere else in the world have so many full sized cartoons for stained glass of this period been preserved.” The drawings put me closer to the artist’s hands and intentions than the finished windows do. Plus you get a whole lot closer. They were shown flat in glazed cases. So the only way for a casual visitor to photograph them was to accept skewed angles at close range through glass. Yet the draftsmanship and emotion come through. (Fortunately the University of Chicago Press in 2012 issued a book on the cartoons. See: http://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/C/bo13191584.html)

An equivalent experience–i.e of seeing the sketches that led up to masterworks–happened in Pisa during a visit in 2012. This occurred at the Sinopia Museum. The walls there were lined with the preparatory drawings for the frescoes from the Camposanto, the elegant cemetery building that was turned to rubble by Allied bombing during World War II. The sinopia were discovered beneath the remains of the Composanto’s frescoes. The Composanto haas since been rebuilt, and many of the frescoes have been at least partially restored.

Here are some of the images I took of the Gouda drawings.

cc

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/belgium-and-the-netherlands-the-paper-trail/trackback/

HI Scott, FANTASTIC! What a great treat for you and for us to see. Vallotton has been one of our favorites for many years. The trip must have been a mind blower for someone like you (and us).

Thank you for sharing.

Regards,

Lee