Bed Exchange

Introduction

Antique beds are not so imposing when disassembled, not even high-post beds like these. Each set includes four turned posts, four rails that connect the posts about two feet off the floor, a headboard (the one for the bed on the left is not pictured) that fits into slots on the two unreeded pair of posts, and a set of replaced testers (boards that connect to the top of the posts). Both beds were American made–the one on the left c. 1800 and the one on the right c. 1820–with posts and headboards of tropical mahogany, rails of native woods (I believe cherry for the one on the left and birch or maple for the one on the right.) The replaced testers for both beds are pine. (Testers were designed for supporting drapery.)

The bed on the left arrived Sunday, July 10, after it was purchased from Lisa Minardi of Philip Bradley Antiques of Sumneytown, PA, about 50 miles north north west of Philadelphia and too far for me to drive to see it. Fortunately after I first saw the bed on Incollect.com, Minardi was very kind and patient to answer my many questions and provide photos to supplement the ones online. She even asked a visiting furniture expert to verify for me that the headboard was original to the bed.

The bed on the right was purchased about 1990 from James Wilhoit, an Annapolis antiques dealer, during the Hunt Valley Antiques show north of Baltimore. I was going through the motions of being an antiques picker at the time. The deal with Wilhoit involved trading his bed for a c. 1820 Massachusetts wing chair with a broken back leg that I bought from (Tommy) Foster’s Antiques in Wexford, PA, north of Pittsburgh. Plus I paid Wilhoit $1,200.

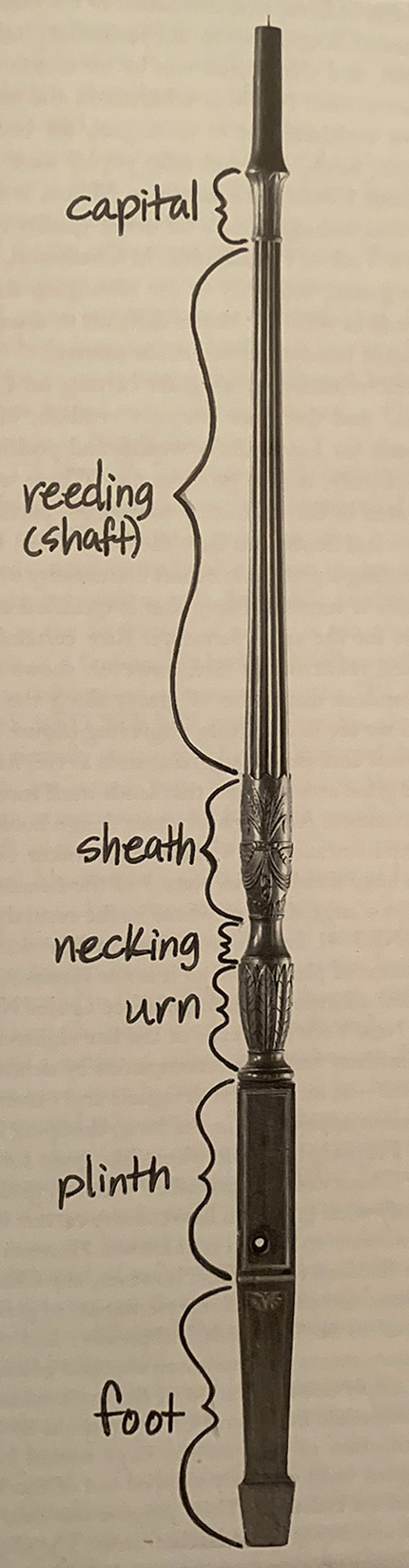

We certainly enjoyed sleeping in Wilhoit’s bed for over 30 years, but one issue bothered me. Soon after we assembled it, I started to believe that the posts had been shortened because the posts were in two pieces and that the part of the posts called the capital were missing and because the two pieces were glued together where the capital would have been. Of course I was assuming those posts ever had capitals like the one in this diagram from “Volume II: Classical Furniture” in The Furniture of Charleston 1680-1820 (Bradford L. Rauschenberg and John Bovines, Jr, The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salen, NC, 2003)

Here is where I thought that the capital would have been on our first tall-post bed.

So the idea of replacing our first bed happened long ago, but replacing it was not a matter of willpower. There just haven’t been that many tall-post beds on the market, and what there were invariably far exceeded by pocketbook. Part of the reason is stated in the Charleston book: “The attrition rate for bedsteads, particularly tall-post examples, is certainly much higher than for chairs or chests of drawers, whose utility has not lessened with time…. The invention of steam heat, coupled with inexpensive mass production of window screens, left draperied bedsteads bereft in most cities by 1900. There was no longer a need to cloak a bed in drapery to ward off chilling drafts, or to pavilion its posts in silk gauze to turn away droning nocturnal insects. And as ceiling heights plunged virtually to seventeenth-century levels during this century, bed cornices were discarded or sent to the garret where heat destroyed veneered friezes and loosened moldings. Even worse, bedposts, which not infrequently exceeded eight feet in height, were either cut down or entirely sawn up for fireplace fuel.” (Vol. II, pg. 788-89)

Upgrade parade

Purchase of the high-post bed in 2022 is in a way the culmination of the upgrades to the American antique furnishings for our three-story (plus kitchen on the ground floor) Baltimore townhouse, which we bought in 1993 with so little furniture that we left some rooms empty at first….but not for long. Oddly enough the sequence of upgrades began in 2015, while on fixed income (having retired as a design editor for the Baltimore Sun print editions in 2011). Three things facilitated these upgrades: 1) the steady rise in the value of retirement investments, 2) the growth in my knowledge of American antique furniture c. 1800-45, and 3) the relative softness of the market for American classical furniture.

The following is the chronological sequence up upgrades. If the upgrade was presented in a previous ART I SEE blog post, I’ll provide the link.

The two chair backs above represent two sets of six Pennsylvania painted windsor chairs. The one on the right is from a set we purchased at the Black Angus Antique Mall in Adamstown, PA, in 1994. These chairs were made in the hundreds from c. 1840-60. There was nothing wrong with this set except its brown base color was too dark for our ground-floor kitchen. The one on the left was made by John Swint. He signed one of the chair bottoms with his name and street address in Lancaster PA. He was active from 1845-50. We bought the chairs in 2015 from Steve Smoot at a fall York, PA, antique show. As part of the deal he also purchased our old set. At a subsequent York show it was weird to see that set for sale. The Swint chairs had been sold at an auction by Jeffery S. Evans & Associates of Mt. Crawford, VA, on 20 June 2015. I first mentioned this chair upgrade in a previous post: LINK.

Once again two very similar items. Both were Eastern Massachusetts products. In both, the lyre-supported mirror is attached to small three handkerchief drawers which in turn rest on a case with a set of drawers. The one on the right was purchased in 1980 from C.U. Antiques, Mardella Springs, Eastern Shore Maryland. Had I had the faded finish redone and the pulls replaced as I once planned, I might not have sent it to auction after I bought the chest on the left. I really liked it. The alternating direction of crotch mahogany veneering on the case drawers was super. However, when I first saw the one on the left at the 2018 Delaware Antiques Show, I couldn’t get it out of my mind. Then when the dealer Steven F. Stills brought it to the fall York Antiques Show in 2019 with a lower price, I couldn’t resist. The corner posts and legs exhibit all the hallmarks of fine Boston cabinetmaking c. 1810-20. The mirror frame and lyre supports retain original gilding and hand painting. The finish is probably original. So are the lion’s head pulls with traces of gilding. The only loss in the upgrade was one less wide drawer in the case section.

Just a month later…. In another six for six upgrade, we bought six red upholstered side chairs in 2019 to replace the set of five side chairs and one armchair on the right. We bought the latter set in 1987 from the J. S. Pearson Co. of Baltimore County. We thought we had a handsome set of maybe Philadelphia chairs c. 1815-25 until we sent them to Adajian & Nelson furniture restorer for regluing. Whereupon the restorer discovered that three of our chairs weighed noticeable less than the others. On further inspection we realized the carving on the stay rails of the heavier chairs was better executed than that on the other three. We knew then that our dining room chairs needed an upgrade. Just 32 years later we did so when we purchased the Phyfe-attributed New York chairs, c. 1835-40, from Charles Clark at the 2019 Delaware Antique Show. The chairs were part of the Richard and Beverly Kelly Collection, sold by Northeast Auctions on 3 April 2002. The accession of the red chairs were previously mentioned in a January 2020 blog post: LINK.

While not exactly comparable, the c. 1820 Baltimore washstand (left) replaced the suspected c. 1900-30 Baltimore work table in April 2020. The latter, which we used as a bedside table, is a form that often served as a work space for the woman. Many have a compartment for sewing/knitting and sometimes have a writing surface for letters. The small size and castors made them easy to move. The washstand with its marble top and pullout bidet was definitely needed in the bedroom. Once I bought the washstand from Spurgeon-Lewis Antiques in Alexandria, VA, in 2021, the work table became extraneous. While federal in look, it was a couple inches too tall and assembled with dowels instead of rectangular tendons. The acanthus leaf carving of the urn and legs, however, was quite successful. I bought it from Ruth Rogers on Baltimore’s old Howard Street Antique Row in 1985. The washstand (and a near identical companion) previously sold in November 2017 at Alex Cooper auctioneers in Towson, MD. (LINK)

This upgrade was featured in a May 2022 ART I SEE bog post: LINK. Both chairs are fine examples of Baltimore fancy chair making c.1820-30. The chair on the left (one of six) had little in the way of surviving original paint. We bought the set at Philip H. Bradley Co. (when it was in Downington, PA) in 1993. The chair on the right is one of four chairs that we bought at auction in September 2021 from Miller & Miller Auctions in Canada. Their original paint has survived to an extraordinary extent. Once they arrived, I donated the set of six to the Riversdale House Museum in Prince George County, MD., because the mansion already had four very similar chairs.

Bed Comparison

As noted the beds are quite similar. Consider the dimensions. Our bed to be sold measured when assembled: H 90 1/4″, L 78 3/4″, W 63 1/2″. Our new bed: H 96″, L 79 1/4″, W 60 1/2″. Both were rope beds, with a series of pegs atop the rails for attaching ropes to support a mattress. The pegs on our first high-post bed had been sawn off flush to the top of the rails. The newly bought bed retains its pegs. Both could accommodate a modern queen mattress. Some folk might believe that beds of that width were uncommon in the era 1800-20, but neither bed show any indication that the end rails or headboards had been modified.

The beds also are similar in that the foot posts are more articulated than the head posts. If you scroll back up to the first pair of photos, you’ll see that for each bed one pair of posts is reeded (the foot posts) and one pair lacks reeding (the head posts). Leaving the head posts less articulated was quite common because those posts were often concealed by fabric.

If you compared foot posts–our first bed on the left and our new bed on the right–you’ll they mostly follow the diagram in the Charleston book. From the bottom up, there’s a foot, a plinth (where the rails attach), an urn, a neck, a sheath (on the new bed only), a reeded shaft, and a capital (missing on the old bed).

The most notable difference is the feet. Our new bed was probable made around 1800 when a tapered, square (in cross section) leg terminated in a “spade” foot. By the time our first bed was made, c. 1820, that style leg was old fashion and superseded by a turned leg.

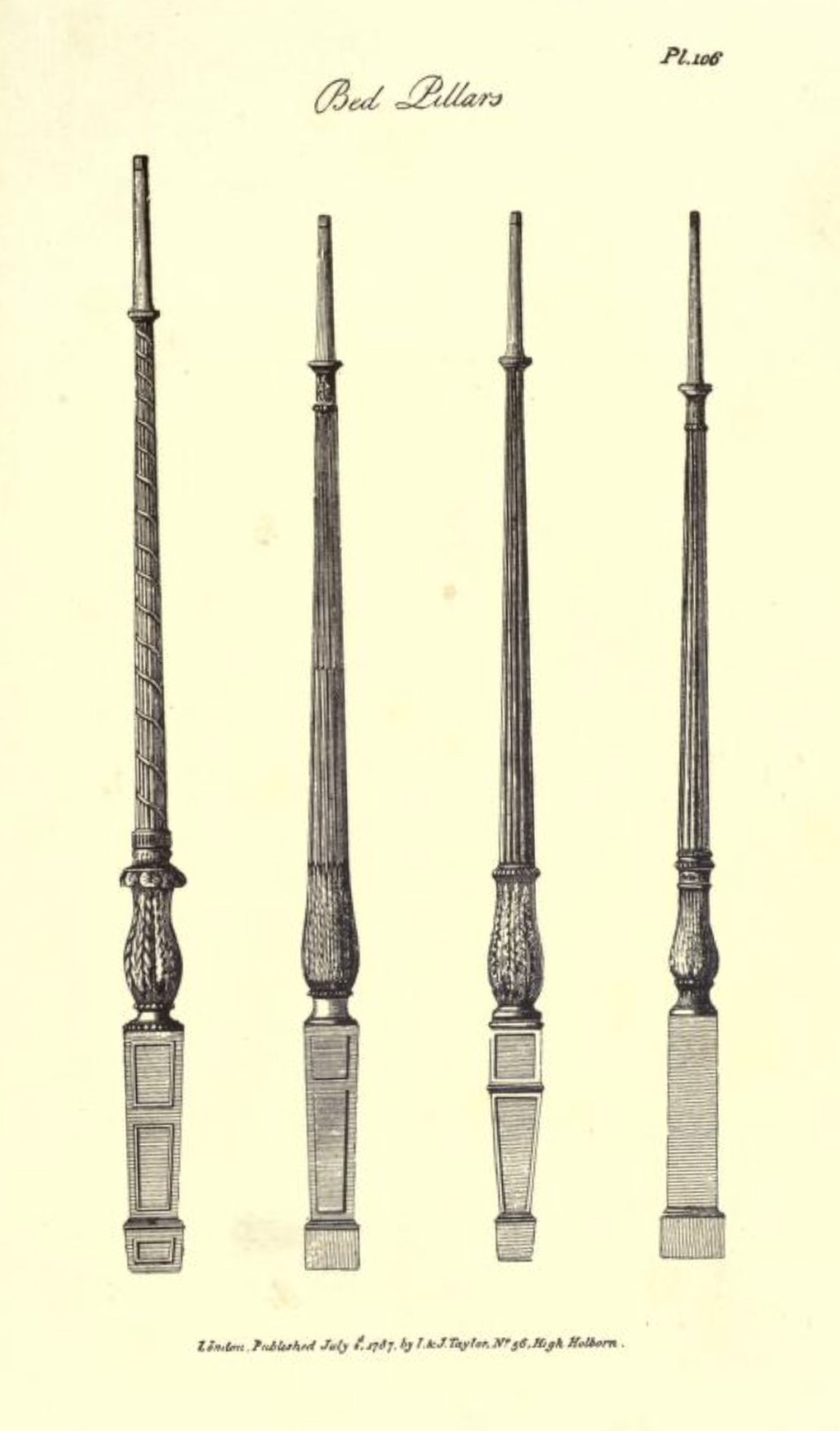

Above right is Plate 106 from George Hepplewhite’s book A Cabinet-Makers and Upholster’s Guide (London, 1790). Instead of using the word “spade” to denote the foot, he referred to them as “term” feet. (The complete book is available online: LINK.) In 1793 another English cabinetmaker Thomas Sheraton also published a very influential design book–The Cabinet-Makers and Upholster’s Drawing Book. (Also online: LINK.) This book popularized the turned leg.

The shapes of the reeded shafts differ too. The shafts of our first bed, which lack the sheath, are widest about a third of the way above the urn. The shafts of our new bed are widest at the sheath and then narrow quickly above the sheath.

Aesthetically, the biggest difference between the beds is the carving on the newly bought bed, missing on our first bed.

A ring of small leaves adorn the base of the urn on the foot posts of our new bed, while a fringed swag, suspended by a ring, is draped above the leaves. The carving is repeated thrice around the urns. The leaves, often named “water leaves,” are fully articulated on the sheath. There are six leaves carved on each sheath. The tops of six other leaves peak out between the fully carved leaves. These twelve leaf tops alternate with the twelve reeds of the shaft. In shouldn’t be too much of a surprise that the lesser adorned foot posts of our first bed also have twelve reeds. It must have been an easy way to divide up the circumference of the posts: three reeds per each quarter of the circumference.

Had our first bed retained its capitals (assuming it had them), it’s unlikely it would have been carved. The number of leaves carved onto the capital of our new bed duplicates the arrangement of the sheath.

I was going to expound upon the origins of urns and swags in the American federal period–1780-1840–and cite design books like those from Hepplewhite and Sheraton, but I decided not to. Instead I’ll just offer the photo above from, I believe, Quincy, MA, to suggest how ubiquitous certain motifs were. Could my bed and this tombstone have been so alike if that was not the case? Both have urns with a ring of leaves above the foot, and both have swags suspended by rings.

Contemporary bed

Thanks to Gregory R. Weidman, curator of the Hampton National Historic Site and Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine, the two photos above show a high-post bed quite similar to our new bed. The photo on the left is from the 2002 Sotheby’s catalog for the sale of Pamela Copeland’s collection. She married Lammont du Pont Copland, a cousin of Henry Francis du Pont. In an email, Weidman wrote: “She bought the bed in 1957 from Joe Kindig, the famous antiques dealer in York, PA. The bed came with Ridgely of Hampton provenance. We know that Kindig used to come to Hampton occasionally during the Great Depression and buy early furniture from John Ridgely, Jr.”

The photo on the right shows the bed installed with a new cornice at Hampton. Weidman gave the dimensions (pre-cornice) as H: 94″, W: 72″ and said it was “made in Mid-Atlantic region, probably Philadelphia, 1795-1815.”

As you can see, the foot posts share the overall profile of that of our new bed. The carving is similar too. On the urn the Hampson bed lacks the ring of small leaves beneath the swags but adds a beaded ring above the swags. The legs on the Hampton bed are shorter and the rails are closer to the floor.

Making the switch

Here are two views of the transition. On the left, our first bed is in the foreground, while our new bed is in the foreground in the photo on the right. The plywood boards are sitting on our new bed. We had just moved them off the first bed. They had been cut to fit in the recesses of the rails–where the pegs had been–and notched around the posts.

When the boards were placed on the rails of our new bed (which is 3″ less wide), it became imperative to enlarge the notches as the scribe marks show (left photo). Yet once the notches were enlarged and the pieces of plywood were fitted around the posts, there was a gap that required a narrow piece of plywood to fill.

This photo shows that several steps have been completed. The gap in the plywood has been remedied. Lengths of 1-by-1s were screwed onto the perimeter of the plywood so that the plywood would not rest on the tops of the pegs. Then the raw edges of the plywood and 1-by-1s were stained. Only removal of the plastic and the pieces of wood that elevated the 1-by-1s was needed before the mattress could be placed.

Next

I purposely overlooked one upgrade that preceded the bed. It was too significant to simply note as an upgrade in this post. So I’m planning a separate ART I SEE blog post on the transition illustrated below.

Comments

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/bed-exchange/trackback/