Barbara Paca: Rescuing Ruth Starr Rose

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

When I learned that Baltimore’s Reginald F. Lewis Museum was planning an exhibition of artworks by Ruth Starr Rose (1887-1965), my reaction was twofold: (1) I remembered how wonderful it was to come across a stack of her lithographs at a Chestertown, MD, antiques/art gallery in 1984, and (2) I immediately decided to contact Barbara Paca, the guest curator of the Rose exhibition. What was striking about Rose’s lithographs was that her subject matter dealt with the lives and spiritual world of rural African Americans. Rose, however, was a white woman, whose wealthy Wisconsin family moved to Maryland’s Eastern Shore and bought Hope House, a former tobacco plantation, when Rose was 16. What was striking about Paca was she was not a curator by profession, although she does have a Ph.D in art history Rather she is landscape architect and owns Preservation Green, with a storefront in Manhattan. She is a direct descendant of William Paca, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Hope House, it turns out, was built by her ancestors.

When I called Paca, my intention was to write a blog post on Rose. But during our phone conversation–as Paca described how how she has championed the mostly forgotten artist, how she purchased Rose art and ephemera whenever she could, and how much resistance she experienced from museum curators whom she contacted in hopes of securing a venue for a Rose exhibition–I realized that Paca herself could be the subject of an ART I SEE post. Paca was immediately helpful. Besides answering my numerous questions, she emailed me a PDF of the exhibition catalog–Ruth Starr Rose: Revelations of African American Life in Maryland and the World–from which I gleaned information on both women.

Images of Ruth Starr Rose artwork are used with permission from the Starr Estate

RUTH STARR ROSE, briefly

When the Starr family moved to Hope House, in a way the Starrs inherited–and lucky for them–the services of many of the African American residents of the Talbot County village of Copperville. These folk were hired for day-to-day chores, and they were essential in helping to rebuild the wings of plantation house and restore the gardens. Leslie King Hammond in the catalog introduction wrote:

When the Starr family moved to Hope House, in a way the Starrs inherited–and lucky for them–the services of many of the African American residents of the Talbot County village of Copperville. These folk were hired for day-to-day chores, and they were essential in helping to rebuild the wings of plantation house and restore the gardens. Leslie King Hammond in the catalog introduction wrote:

Rose became an active participant in Copperville society, and she developed a profound respect for and understanding of black life and culture. From the 1920s through the 1940s, Rose was a member of the DeShields United Methodist Church, where she worshipped and taught Sunday school. This was an ambitious venture for any woman in Rose’s generation, and it is noteworthy that she did not assume the role of a missionary. Instead, she was drawn deeply into the compelling intellectual and spiritual world of the black church.

Ruth Starr Rose at Hope House in 1915

Photo courtesy of the Lewis Museum

Ruth’s privileged place in society made going to Vassar College possible. She studied in France in 1911-12 and then enrolled in the Art Students League in New York. She married William Searls Rose in 1914 at Hope with the Philadelphia Orchestra performing in the gardens. They honeymooned in Cuba, and her parents gave her Pickbourne farm, adjacent to Hope House, as a wedding present. Now that’s privilege. They lived in a suburb of New York but spent summers and holidays in Maryland. She commuted between New York–her home near there and the Art Students League–for over 30 years.

She was hardly an unknown during her life, having had 43 one-person shows and participated in more than 213 group exhibitions. Prestigious museums–like the Metropolitan, the Corcoran and the Philadelphia museums–hold her work, but, says Paca, “Rose remains conspicuously absent from the annals of art history.”

Well to collectors of American prints of the early and middle 20th century she’s certainly not an unknown. Prices for her prints have gone up about 6X since I bought my two in 1984. But I think I know a little about why some curators my hold her work in little regard. Take me as an example. I had dozens of her prints to choose from. Many were in color like this one:

Ruth Starr Rose, The Golden Slippers, 1947, color lithograph, 9 3/4″ x 12 1/2″, ed. 250, a presentation print of the American Color Print Society

Ruth Starr Rose, The Golden Slippers, 1947, color lithograph, 9 3/4″ x 12 1/2″, ed. 250, a presentation print of the American Color Print Society

My first hesitation is that I rarely buy prints in color. Second, I felt images like that were too cute. Furthermore, I as a white man was uncertain how I felt about a white woman dealing with black subject matter. Not knowing her background, I wondered if she was being patronizing. Here are the two prints I did buy:

(Left) Ruth Starr Rose, I Couldn’t Hear Nobody Pray, 1943, lithograph, 1943, 13″ x 10″, edition unknown (Ponemone collection)

(Left) Ruth Starr Rose, I Couldn’t Hear Nobody Pray, 1943, lithograph, 1943, 13″ x 10″, edition unknown (Ponemone collection)

(Right) Ruth Starr Rose, Nobody Knows the Trouble I See, lithograph, 1942, 13 9/16″ x 10 1/16″, edition unknown (Ponemone collection)

Besides being black and white, these two were based on a reality–soldiers during World War II–I better understood. My father was a POW in Germany after all. Here were soldiers–one a radioman in a Pacific island, the other a soldier returning home–facing dangers and hardships. What I didn’t appreciate until reading the exhibition catalog was that both were entitled after African American spirituals, the same source material as for The Golden Slippers. Nor did I appreciate that Ruth Starr Rosed deeply respected and loved the people of Copperville and integrated herself into their world.

(Left) Jack Jordan (1925-1999), Going Home, woodcut, late 1940s, 12 1/2″ x 9 1/2″, edition unknown (Ponemone collection)

(Left) Jack Jordan (1925-1999), Going Home, woodcut, late 1940s, 12 1/2″ x 9 1/2″, edition unknown (Ponemone collection)

Like Rose in Nobody Knows the Trouble I See, Jack Jordan, a black artist, made returning home the subject of his print. His has a rhythm with all of its curves and a freedom from normal gravity but it lacks the intensity of Rose’s.

Other white artists–contemporaries of Rose–engaged African American subject matter. Some like John Steuart Curry, Louis Lozowick and Lynd Ward dealt explicitly with lynching. Others presented black life with dignity in their prints:

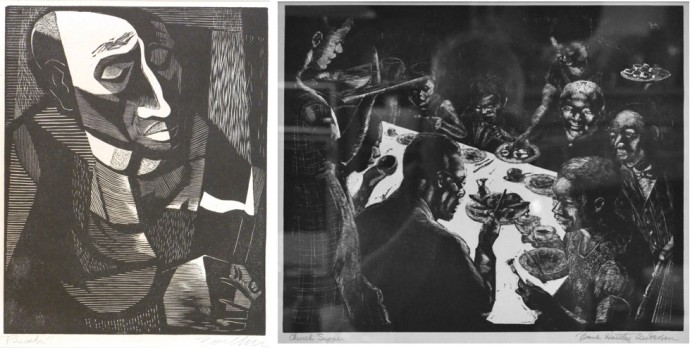

(Left) Richard Zoellner, (1908-2003), Preacher, woodcut, 1933, ed. 25, 10″ x 8″ (Ponemone Collection)

(Left) Richard Zoellner, (1908-2003), Preacher, woodcut, 1933, ed. 25, 10″ x 8″ (Ponemone Collection)

(Right) Frank Hartley Anderson (1891-1947), Church Supper, wood engraving, 1936, ed. 60, 10 3/8″ x 12 7/16″ (Ponemone Collection) (Sorry for the reflections on the glass)

But no one but Ruth Star Rose seemed to speak from within the African American community.

BARBARA PACA

Barbara Paca standing beside the Ruth Starr Rose painting Anna May Moaney. (Photo by Sean Donnola)

Barbara Paca standing beside the Ruth Starr Rose painting Anna May Moaney. (Photo by Sean Donnola)

In her preface to the Rose catalog, Barbara Paca described, when visiting an Eastern Shore art restorer, “my first encounter with the black Mona Lisa.” She was surprised to learn that the artist of Anna May Moaney (the real title) was white.

I knew the Eastern Shore well enough to understand that racial divides ran deep, and it was unlikely that any white person would have portrayed an attractive black woman who had dignity, refined features, inherent strength, and a sense of self worth, all while revealing a mutually respectful connection between the artist and the sitter. … This painting contained secrets that made me curious about how a white woman could have painted Moaney as possessing a raw power that exceeded her limited status as a domestic servant.

Ruth Starr Rose, Anna May Moaney, 1930, oil on Masonite, 24″ x 18″ (Photo courtesy of the Reginald F. Lewis Museum)

This brings me to me email interview with Barbara Paca.

While Ruth Starr Rose was an Eastern Shore transplant, apparently you are a member of one of Maryland’s prominent families. Could you tell me about your lineage and where you grew up?

I don’t define myself by those who lived before me. However, to answer your question, I’m the great great great great granddaughter of William Paca. I was born in Southern California and grew up in the Arizona desert and have lived mostly abroad.

How did your upbringing give you perspective on black and white relations on the Shore? What were they like when you were a child? Did your friendships cross racial lines?

There were always two histories–the one in school and the one in our family. My grandmothers were both English. Grandmother Paca was born in Jamaica. Her father was a British naval officer. Her grandfather, who was fluent in Zulu, was a British agent during the Ashanti wars. His wife is recorded as stating that, should she ever become a widow, she would choose to raise her children among the Zulu as they were the most noble and honorable people on earth.

Safe to say that as a family, we had a unique weltanschauung. [https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/weltanschauung]

How did your interest in landscape architecture develop? What was your training (schooling)/apprenticeship? Can you tell me briefly about your business today?

Our family has always worshiped gardens and native plants. My father took us out of school for days to watch the desert bloom. We used to travel to Mexico for the equinox to study sea life trapped in the tidal pools.

At age 16 I attended the University of Oregon, where I received a five-year professional degree in landscape architecture. I went on to receive a Ph.D in history of art and architecture at Princeton, then a Fulbright scholarship, then another post doc at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study.

I never wanted to go to college. I wanted to teach Outward Bound and study the botany of extreme climates in alpine environments and also along coastlines.

[She never discussed her business with its Manhattan storefront, an Oxford (MD) Think Tank, and an Atelier in Paris, but you can learn more at her firm’s website: http://www.preservationgreenllc.com/]

Your introduction in the Rose catalog describes your first purchase of a Rose painting. When was that? Did you see anything providential in that you learned that Ruth lived at Hope plantation, where you had a job as landscape historian?

The painting was purchased c. 2005. Considering the fact that Hope was built by my forebears, it all seemed quite normal in an extremely coincidental meant-to-be kind of way.

How would you describe your art collecting before then?

Modest as it is now.

Did you immediately start pursuing Rose artworks? Or did that gradually develop?

I was only interested in making purchases to help me tell her story.

In the catalog, you mention buying collections of Rose artwork and ephemera. Did you buy from Rose heirs?

The collections were purchased from art dealers in New York and the United Kingdom.

Did you seek out her art in museums? What was your reception? Which institutions were most helpful or had a number of Ross artworks?

People in museums were uncomfortable with Rose as an artist. If you read my preface, you will see the story about how middle-class white male curators always degraded her as an artist, labeling her work saccharine and amateur at best. They also labeled her the “rich white lady who made fun of black people.”

Did you specifically approach the Baltimore Museum of Art? If so, what was the response?

No, I never approached the BMA.

When and how did you meet Rose kin? Who were they, and how did they assist you?

Her family has been wonderful, particularly her granddaughter Brenda Rose and her great nephew Nathan Kernan and his partner, Thomas Whitridge..

When did you conceive the idea of a Ruth Starr Rose exhibition? Did the idea slowly develop or was there ah-ha moment?

The more I learned her true story, the more I realized that she had been trivialized by mediocre people. So in conversations with friends the idea of an exhibition was born, and with their help it happened.

What did you do to drum up interest for a Rose exhibition?

Theodore Mack, former chair of the Maryland Commission on African American History and Culture, and his wife Betty Mack paved the way. Without hesitating, he organized a meeting with the Lewis Museum. And he stayed close to the project for nearly four years as we planned details and continued research to make sure her story was accurate.

Which institutions/individuals were most supportive? When and from whom did you get some encouragement? When did the Lewis Museum give the green light?

The Lewis Museum was and always has remained supportive. There was no question that with Ted Mack and others we could get the project done on a level that was commensurate to her skill. The second most helpful person was the graphic designer Mary Shanahan, former art director to Rolling Stone, French Vogue, GQ; creative director to Town & Country, and book designer to Richard Alvedon. She was particularly helpful in packaging the entire exhibition, from the catalog, to the posters, note cards, postcards, even church fans for promotion of the exhibition.

Thirdly, the descendants of those portrayed by Ruth Starr Rose were generous with their time in helping me to understand the importance to the African American community of Rose’s contribution. Their story became THE story, as our focus shifted from the artist to those whom she so eloquently painted.

Finally, Deborah Nobles-McDaniel, Manager of Collections at the Lewis Museum, was meticulous and made sure that things went smoothly from the museum side.

What about financial support? How did you manage it?

Again, Theodore Mack is the person behind bringing our great patron, Brown Capital Management, to the table. After our first meeting, Mr. and Mrs. Eddie Brown offered six figures toward the show. I was speechless, but I have learned over the years that their generosity to Baltimore knows no bounds.

You also took on the roll of writing the exhibition catalog. When did that begin and what did it entail?

Catalog was begun over two years ago. My collaborators Leslie King Hammond and New School Dean Nina Khrushcheva were amazing helpers. As the one who was with me during the first discovery of Rose’s work, Professor Khrushcheva has been an extremely erudite sounding board. As mentioned before, the catalog would not have happened without Mary Shanahan’s professional insistence on a first-rate book with attention devoted to every detail.

In your catalog introduction, you said got to meet some of the Shore’s black population. How were you received? In what ways did these folk contribute to your work? How was Ruth Starr Rose remembered by them?

The African American descendants of those painted by Rose have been of immeasurable help (as mentioned above). Living in a close-knit community, I learned that they held Rose and her entire family in high esteem as they were made a part of the extended family.

Did your appreciation of black citizens of the Shore change by these encounters? What did these folks say about racial relations on the Shore today?

No change. We have always been friends. We don’t discuss racial relations on the Shore today, but I know that they are proud to be included among the founding black families of America.

Could you also add the Maryland itinerary and dates for the Rose exhibition?

Still confirming dates. However I can say that the exhibition is next going to be at the Armory in Easton from late April until early July. And it is also confirmed for St. Johns College’s Mitchell Gallery of Art from December 2016-March 2017.

INSTALLATION IN PROGRESS

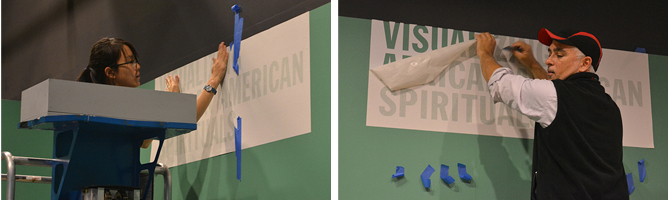

Helen Yuen, Director of Marketing for the Lewis Museum, kindly granted me permission to photograph the exhibition during installation Thursday, Oct. 1. It’s always fun to have the rare opportunity to see a work in progress. It was also a treat to see that a number of Rose’s lithographs were framed together with preliminary sketches.

Jane Yoon, Exhibit Tech, (left) and Dave Ferraro, Director of Architectural Services, hang banners for the Rose exhibition.

Jane Yoon, Exhibit Tech, (left) and Dave Ferraro, Director of Architectural Services, hang banners for the Rose exhibition.

Still wrapped up, an 18th-century American cradle, which was used by the Starr family at Hope, sits near (wall, left) the Rose lithograph called Madonna, in which Anna May Moaney tends to her infant in this same cradle.

Still wrapped up, an 18th-century American cradle, which was used by the Starr family at Hope, sits near (wall, left) the Rose lithograph called Madonna, in which Anna May Moaney tends to her infant in this same cradle.

Ruth Starr Rose, Madonna, lithograph, 1934, 12″ x 14″, together with its charcoal and pencil study.

After hanging a wall of lithographs, Dave Ferraro placed them in a cart so he can then position an exhibition banner.

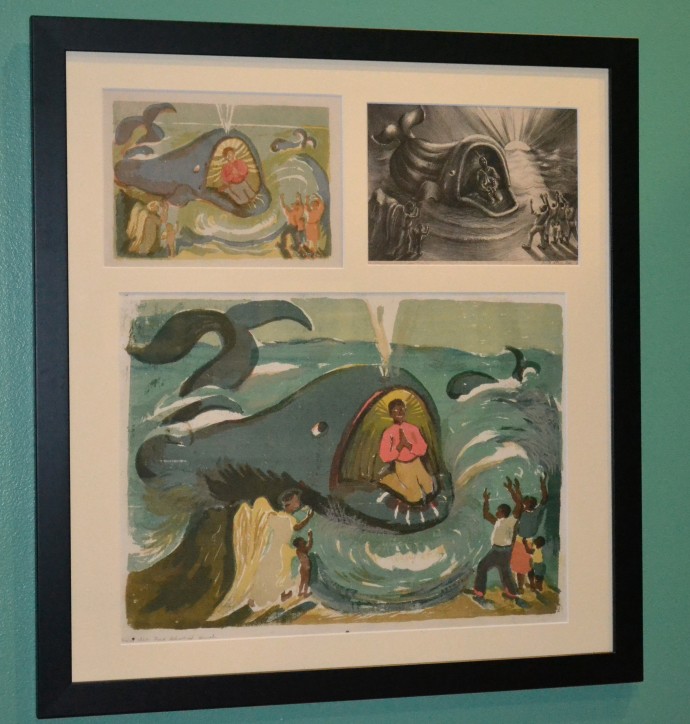

(Left) Ruth Starr Rose, Navajo Fire Dance, 1951, lithograph, 10 1/8″ x 13 7/8″

(Right) Ruth Starr Rose, First Communion, ca. 1946, color serigraph, 15 ½” x 12″ (Top) Ruth Starr Rose, Jonah and the Whale, 1936, 6″ x 8 ½”, in both color (serigraph) and black and white (lithograph).

(Top) Ruth Starr Rose, Jonah and the Whale, 1936, 6″ x 8 ½”, in both color (serigraph) and black and white (lithograph).

(Bottom ) Ruth Starr Rose, Jonah and the Whale, 1936, color serigraph, 12″ x 18″

(Right) Ruth Starr Rose, Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, 1941, lithograph, 10″ x 13″ with perspective sketch below.

(Right) Ruth Starr Rose, Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, 1941, lithograph, 10″ x 13″ with perspective sketch below.

(Left) Ruth Starr Rose, Downes Curtis, 1935, lithograph, 11⅝” x 14¾”, with sketch.

Ruth Starr Rose, Pharaoh’s Army Got Drownded, fresco (detail), 1941, 41¾” x 61.” This was painted for a chapel in the Copperville church where she worshiped.

Ruth Starr Rose, Pharaoh’s Army Got Drownded, fresco (detail), 1941, 41¾” x 61.” This was painted for a chapel in the Copperville church where she worshiped.

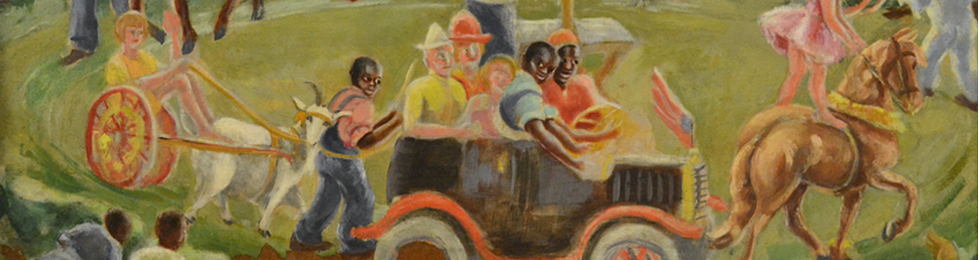

Ruth Starr Rose, The Circus, 1930, oil on Masonite, 30″ x 40.”

Ruth Starr Rose, The Circus, 1930, oil on Masonite, 30″ x 40.”

From the catalog: “The Circus … is situated in front of the old Talbot County courthouse—notably, a site of justice. Rose’s husband is standing on a box in the center of the dynamic circular composition. He seems to be filling the role of conductor and is joined by a black man who is raising a bottle in the air. African American families stand along the left side of the frame and white families are positioned on the right. However, Rose’s son and daughter share a golden buggy with a black child. Furthermore, the roundabout, clocklike movement shows other chariots filled with people of both races, pulled by mules, ponies, and even a goat—suggesting time’s gradual progression toward integration and equality.”

ADDENDUM

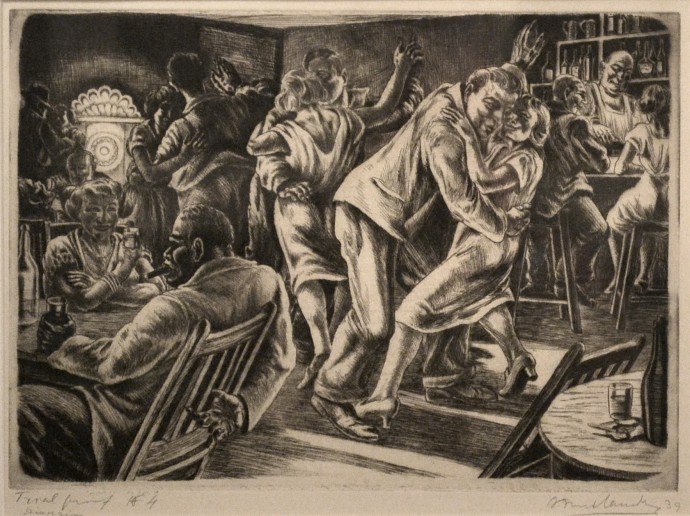

While Rose’s The Circus imagines a circling performance of integration before a segregated audience (in the background up against the courthouse facade), another white artist of the period–Isac Friedlander, a Jewish Latvian emigré–made an etching of an integrated New York tavern scene. Sitting prominently at the table to the left is a black man. The closest dancing patrons and the bartender are clearly white. Maybe Friedlander was depicting a rare instance of integration in American–an artist hangout.

Isac Friedlander (1890-1968), Diversion, 1939, etching, trial proof 4, 9 7/8″ x 13 7/8″ (Ponemone collection)

Isac Friedlander (1890-1968), Diversion, 1939, etching, trial proof 4, 9 7/8″ x 13 7/8″ (Ponemone collection)

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/barbara-paca-rescuing-ruth-starr-rose/trackback/

Pingback: The "Socialite" Whose Art Celebrates the Life of Eastern Shore African Americans Back in the Day | Secrets of the Eastern Shore

I have two prints of Ruth Starr Rose, lived across the street from her son, Richard Starr Rose, went to school with 2 of her grandchildren, Brenda Starr Rose and Richard Starr Rose. I have tried to get in contact with someone that has the same appreciation that I do for her art. I thought I read that her works were on display sometime in April in Easton, MD. Please respond if you can offer any information about this.

Thank you.