Ariel Allweil: Anonymous Jew

INTRODUCTION

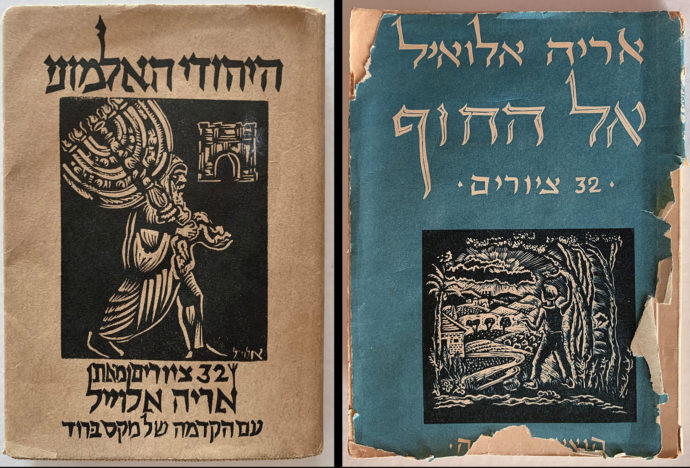

This ART I SEE post, the fifth on the publications of Arieh Allweil (1901-1967), introduces one of two similar books–Anonymous Jew and From a Tour of the Land–that he published in 1939. They are similar in that he illustrated each with 32 linocuts, each have an introduction by Max Brod and each essentially (the linocuts in Anonymous Jew have the briefest of captions) have no text otherwise. Yet they are very dissimilar. Anonymous Jew tells the story of 20th-century European Jews up to the book’s creation from Allweil’s perspective of being a kibbutz pioneer; while From a Tour of the Land is a linocut sequence of landscapes and sights from various places in Mandate Palestine (known among Jews as Eretz Israel). This post presents Anonymous Jew, while the next Allweil post will introduce From a Tour of the Land.

The previous Allweil posts are:

- Introducing Arieh Allweil. LINK

- Allweil’s The Book of Amos: Part 1. LINK

- Allweil’s The Book of Amos: Part 2. LINK

- Allweil’s Tura Afora suite of lithographs. LINK

None of my Allweil posts would have been possible without the tireless and enthusiastic support of his two daughters: Ruth Sperling and Nava Rosenfeld. And I also want to extend my deep appreciation to Jessica Bonn for her translation of the Brod introduction.

The book Anonymous Jew and its contents are presented courtesy of the Estate of Arieh Allweil.

The photographs of the linocuts from Anonymous Jew are presented courtesy of the Estate of Arieh Allweil.

The dust jackets of Arieh Allweil’s (left) “Anonymous Jew” and (right) “To the Shore.” “Anonymous Jew” was published in 1939; while “To the Shore” was published either in 1943 or 1944. (Photos by Scott Ponemone)

The Daughters’ perspectives

Ruth Sperling links Anonymous Jew to her father’s portfolio of eight lithographs that he published in Vienna in 1924. In German the portfolio was entitled Graues Band, and in Hebrew it was known as Tura Afora. (See the link above for the Tura Afora blog post.) By the time he created that portfolio, Allweil already was a pioneer in the kibbutz movement. He helped found the Bitanya [also transcribed as: Bitania] Illit kibbutz in the Galilee part of Palestine. He returned to Eretz Israel in 1926.

She referred to an essay that Prof. Shula Keshet wrote for Galia Gavish’s 2011 exhibition catalogue, Arieh Allweil: From Bitania to Vienna and Back, as a way to describe what she believed Tura Afora portrayed. In an email in 2020, Sperling wrote that Keshet “thought that Tura Afura relates to the pioneers’ story as influenced deeply by the tremendous shock caused by World War I, especially the pogroms inflicted upon Jews. Bitania is the last symbolic stop. Tura Afura is the narrative of the wandering Jew who finally reaches the shore, the place of redemption, only to find even there death and bereavement.”

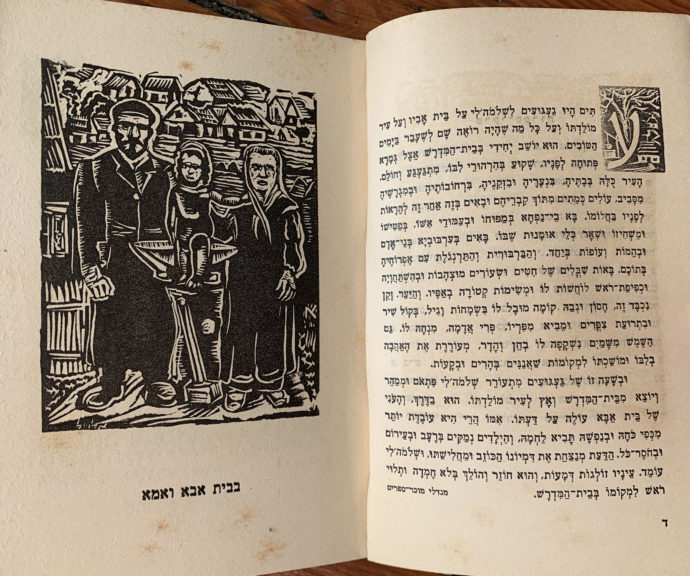

This is the first spread in “To the Shore,” where each linocut is accompanied by relevant Hebrew text that opens with linocut historiated initial. (Photo by Scott Ponemone)

In late March, she commented: “After the discussions for the blog of Tura Afora, it occurred to me that Tura Afora might be a very early version of Anonymous Jew, a version with ‘no filters.’ Fifteen years later Allweil created the Anonymous Jew with the linocuts and their captions, and an introduction by Max Brod. It was culminated by its second edition termed To The Shore. Reaching the destination, it had the same linocuts with the same introduction by Max Brod, yet each page was accompanied by a page from the Hebrew literature and with decorated head letters.”

(As was Allweil’s habit, when he published a new edition of one of his books, it was not just another printing. He often added something new. In the Anonymous Jew to To The Shore sequence, what was new was the Hebrew text opposite each linocut. As another example, in the 1943/44 second edition of his The Scroll of Ruth (first published in 1939), Allweil added linocut decoration in red ink.)

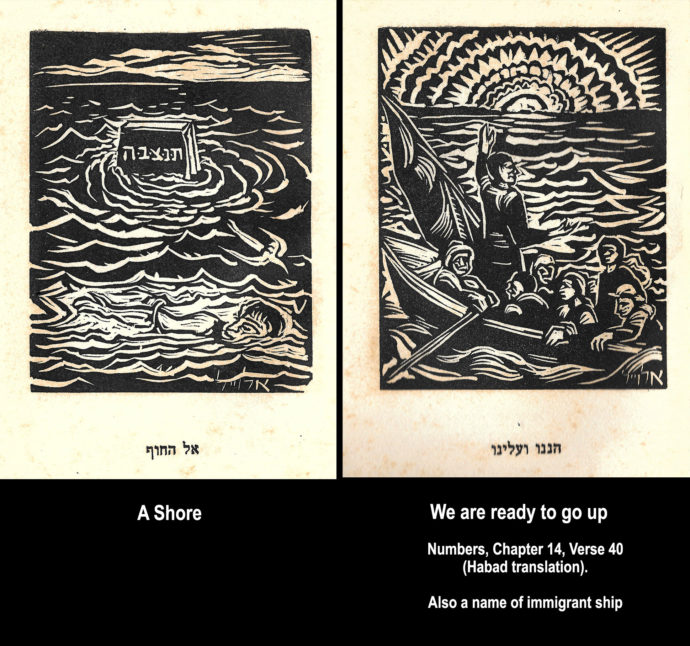

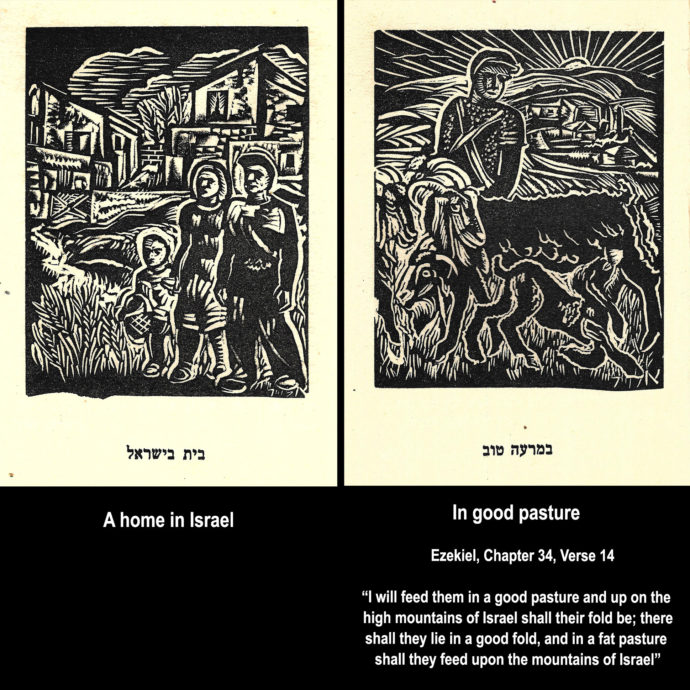

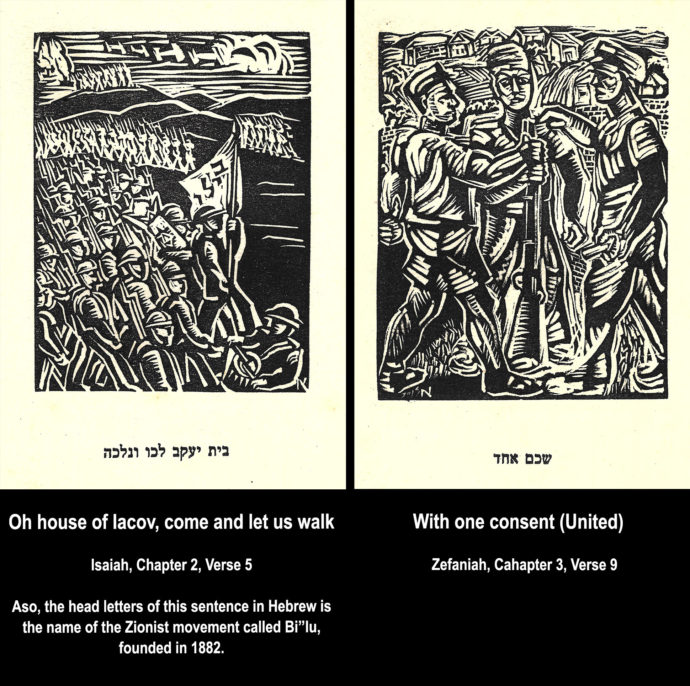

Sperling also wrote: “The three [first Tura Afora, then Anonymous Jew, and then To The Shore] are telling the saga of the pioneer. Starting from his parents’ home and the ‘cheder’ [Hebrew school] the pioneer, who after pogroms and World War I and the sufferings of the war, takes his fate in his hands and made Aliya [literally “going up,” the Zionist term for the journey to the promised land] to Eretz Israel. The wondering and anonymous Jew has reached the shore in Eretz Israel, to build new life. At the time, a number of novels were written in Hebrew about the life of a pioneer. I think the Anonymous Jew is Allweil’s way of telling the saga of the pioneer [“halutz” in Hebrew] in images.”

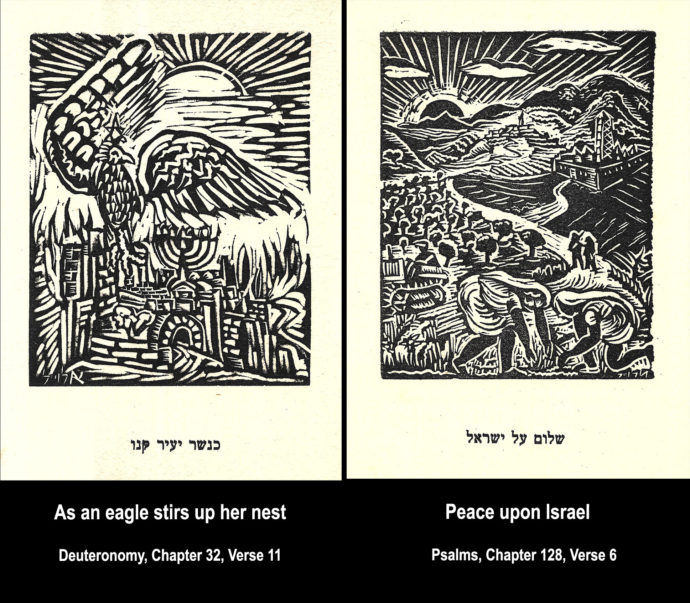

“The book,” she wrote, “ends with hope. Despite the hard work, sufferings and deaths, even in the new country, the book ends with the new life in Eretz Israel and with ‘Peace on Israel’ and ‘As an eagle stirs up her nest.’ ”

In the second linocut in “Anonymous Jew” Allweil pictures himself as a student in Bobrka (Bobroysk), his village in Galicia (in what is now Ukraine).

Sperling’s sister, Nava Rosenfeld, who researched the translations of the captions on each of the linocuts in Anonymous Jew, also sent comments on the book.

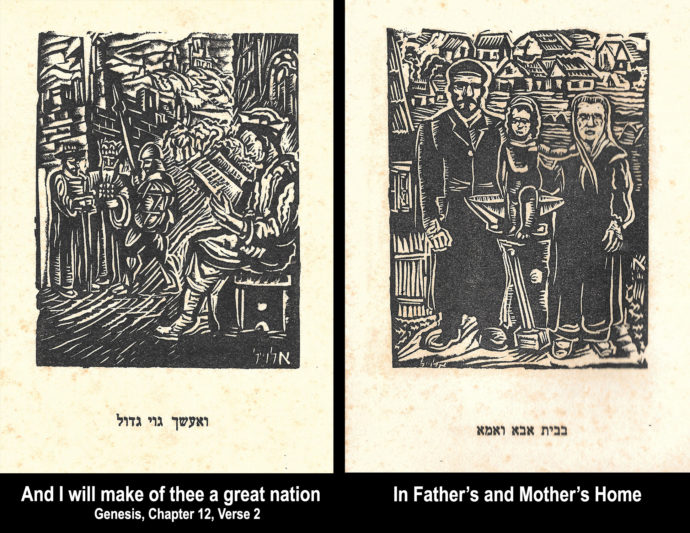

She wrote: “I knew Anonymous Jew all my life. I didn’t understand it at all, but searching to translate the names of the pictures I went to the Bible. By looking at the text in the Bible, I realized what I think was my father’s intention.

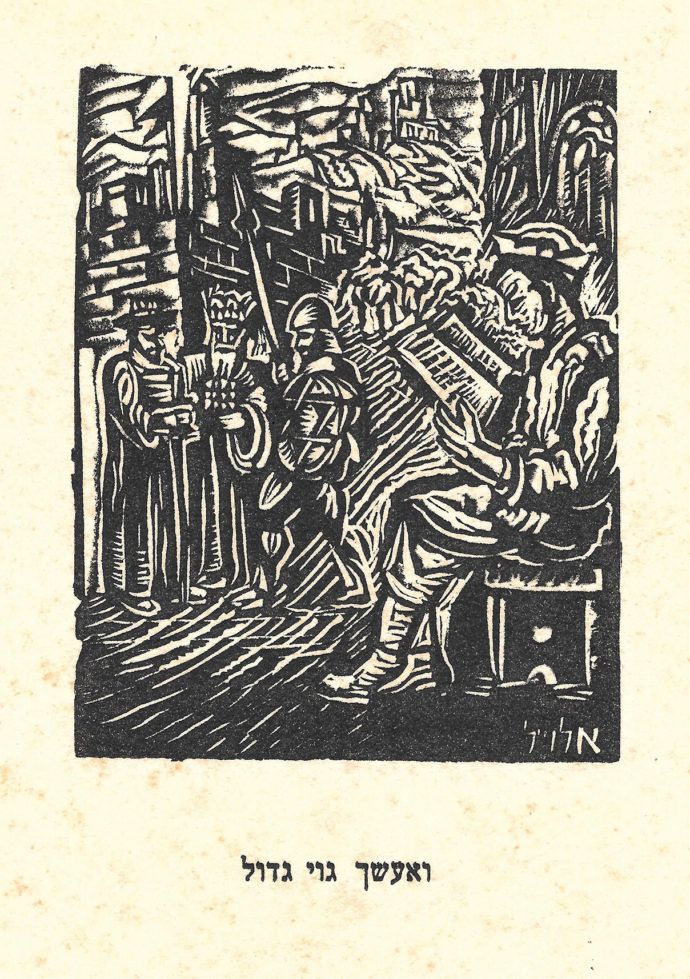

“Let’s take picture No. 2 [right]. ‘I will make thee a great nation.’ (In Hebrew it is just three words.) And what does Allweil paints? There is a young boy, seated reading and dreaming. And the three small figures: Moses? A Rabbi? A Maccabi?

“But when you go to the Bible, God tells Abraham, our nation’s ancestor: ‘Now the Lord had said unto Abraham, get thee out of thy country, and from they kindred, and from thy father’s house, unto the land that I will show thee, and I will make thee a great nation, and I will bless thee and make thy name great.’ (Genesis, Chapter 12, Verse 1-2)” Rosenfeld referred to God’s instruction to Abraham as “the first Aliya. In English you say migration. In Hebrew Aliya means going up (when you go to Israel).”

She then asks: “Is Allweil telling the story of his life [in Anonymous Jew]? He connects the [whole of Jewish] history with his present time. Seating somewhere in Eastern Europe, in a small village, he knows he should go to that land to be free. And that is what Allweil did in his life. He went to Israel.”

She ended by writing: “The story behind Anonymous Jew is also the story of El Hahof (To the Shore), and behind the names is history repeating itself. No crying. Remembering. And building a future for the Jewish nation. The year is 1939. World War II is coming.”

Max Brod’s introduction

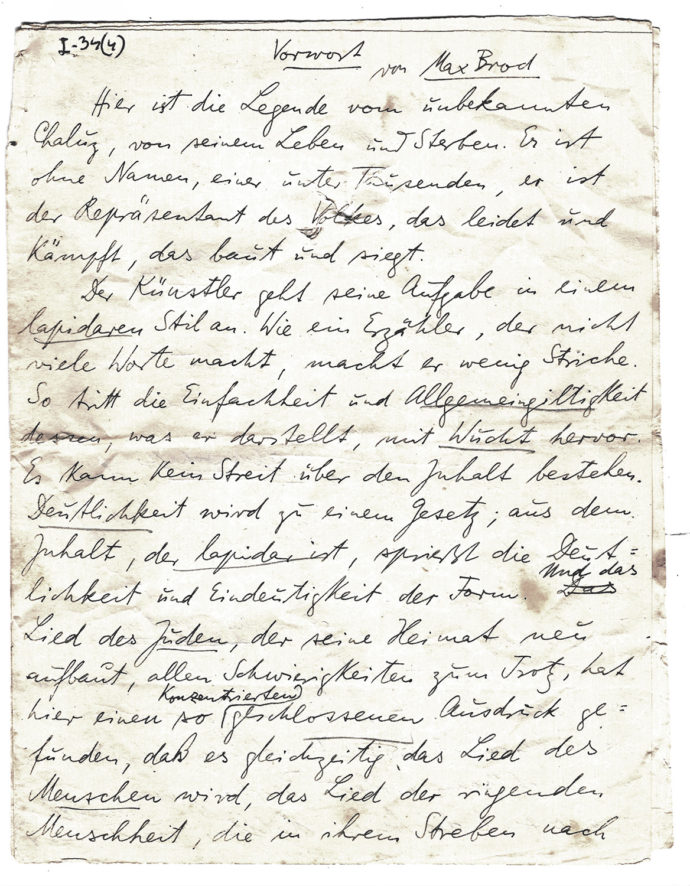

Max Brod wrote his foreword to Allweil’s “Anonymous Jew” in German. (Photo courtesy of the Estate of Arieh Allweil)

By the time Max Brod (born in Prague in 1884, died in Israel in 1968) wrote the introduction for Anonymous Jew, he was already celebrated as the friend and biographer of Franz Kafka. His novels, particularly The Redemption of Tycho Brahe (1916) were highly regarded. He reached Palestine in 1939 to escape the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia. His emigration would place him in Palestine when Allweil published Anonymous Jew, but neither Sperling nor Rosenfeld knew how the two knew each other. As to where they first met, they suspect it was in Europe, perhaps Vienna, before Allweil returned to Palestine in 1926.

Fortunately they have Brod’s original manuscript in German for his introduction to Anonymous Jew, however Jessica Bonn did her translation from the Hebrew as it appeared in Anonymous Jew:

We have here before us the legend of the Anonymous Jew, his life and ambitions. Nameless, one of thousands, a representative of the people, who suffers torture and fights his war, builds and conquers.

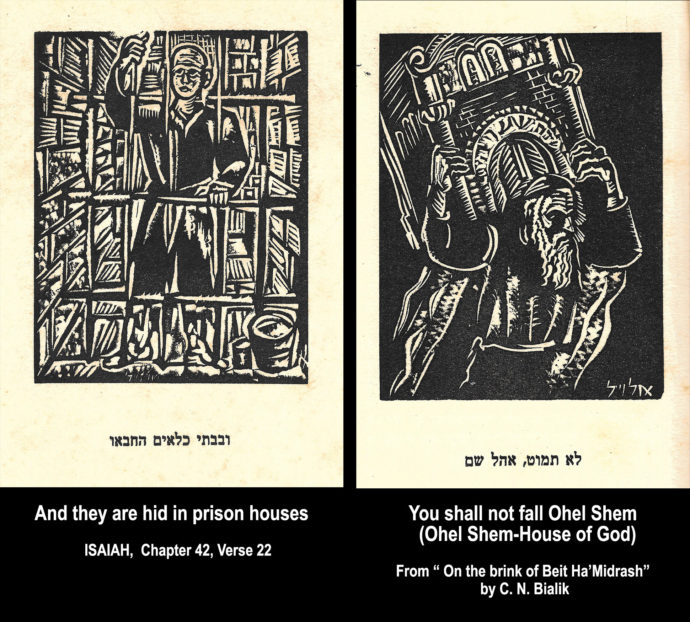

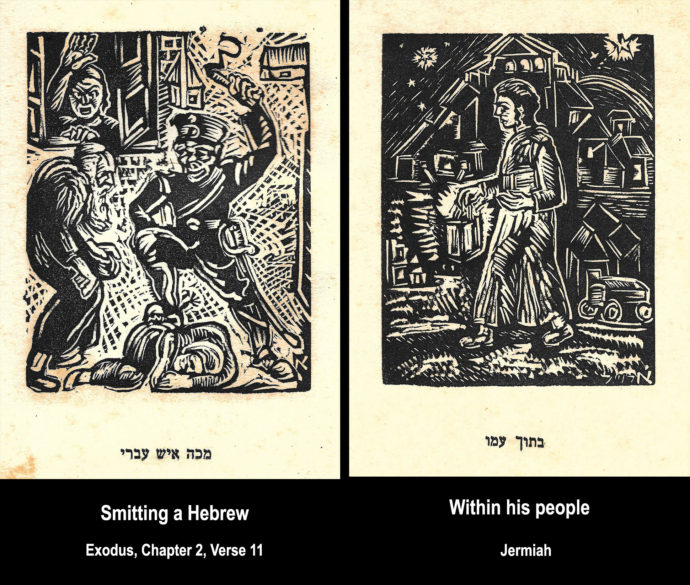

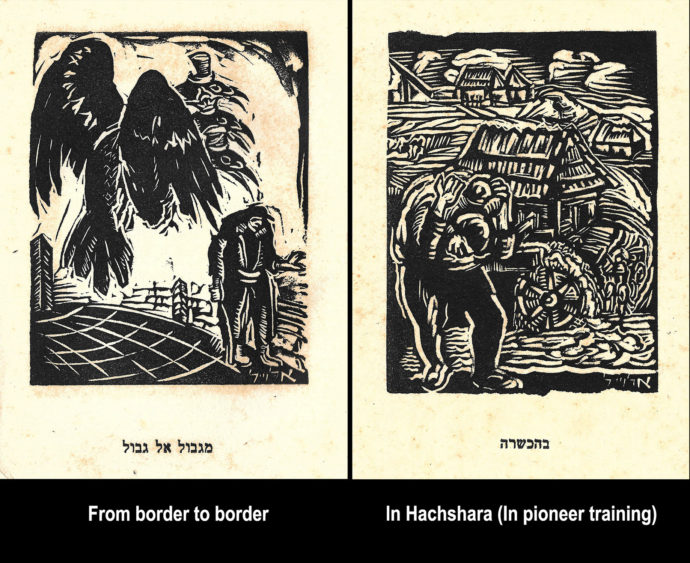

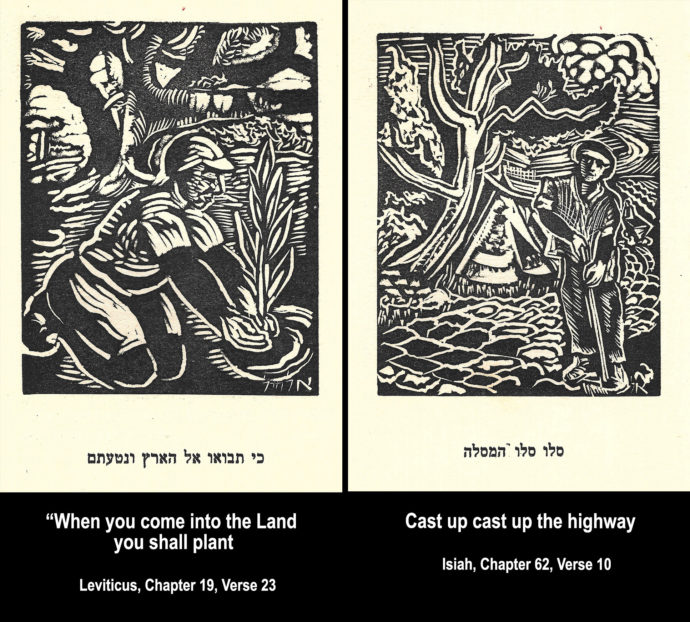

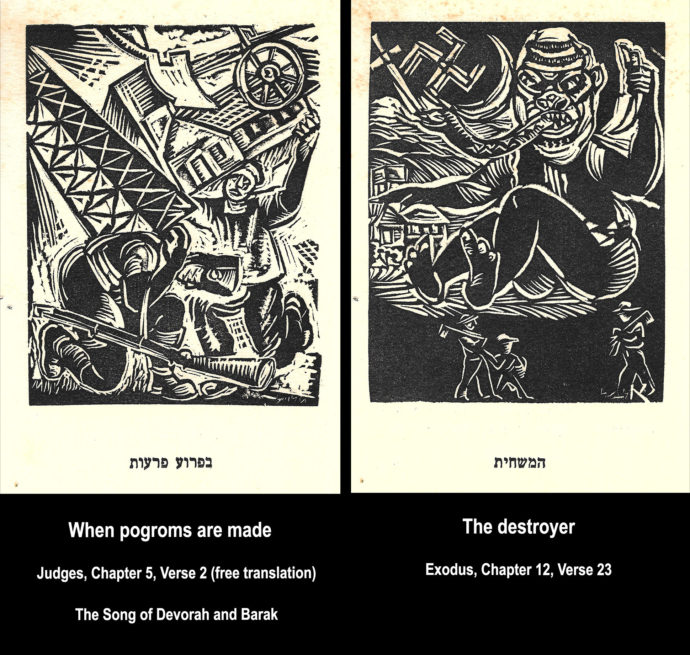

The artist goes about his work in a minimalist and vigorous style. He sketches with sparing lines, like the narrator, who uses succinct language. From these, the simplicity and overarching value of the things he draws are emphasized with boldness and assertion. The content is unmistakable. Evident clarity becomes the rule: through the concise content, the clarity and singularity of meaning in the form are revealed. The song of the Jew, who sets out to rebuild his homeland, despite all of the hardships and setbacks, here finds a concentrated and very particular expression, and becomes the song of mankind, the song of humanity in its struggles, which, in the striving for light defies all setbacks, and returns to its ancestral homeland, fine and flowering, after the cruel enemy has been driven out in a terrible and bloody war. The enemy, which tried to eliminate life, was vanquished by life itself, by the ploughed fields and the tree-filled orchards.

Allweil, the painter, has described here, in his small, pioneer-book, the passionate movement intent on this goal. This explains the surge of emotion, the dynamic stylization of the book. Yet at the same time, Allweil offers us a second book [From of a Tour of The Land–RS], devoted to landscapes, rest and calm. He hints at the eternal nature of the Garden of Eden in our midst, and renders it outwardly visible. The reality of this Eden is conquered step-by-step. The two together comprise the two halves of our renaissance and existence on the land.

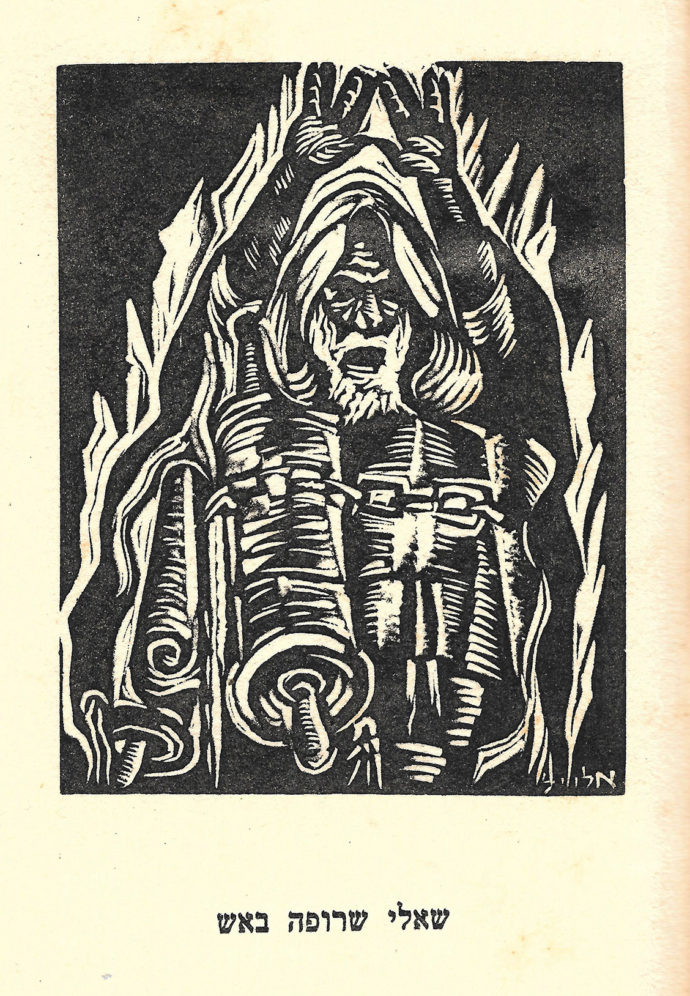

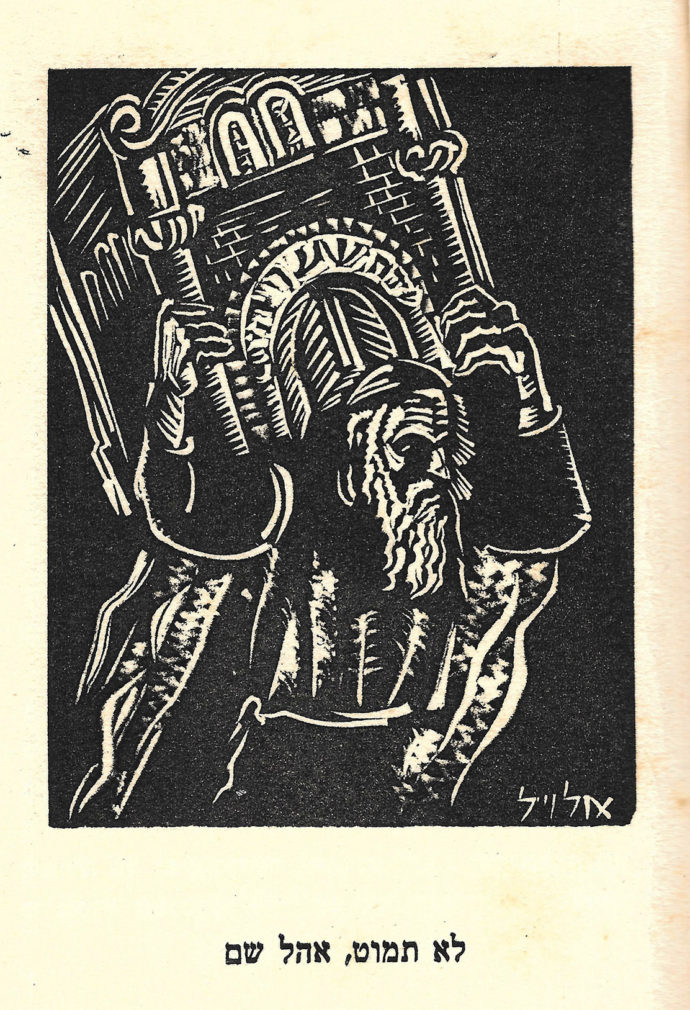

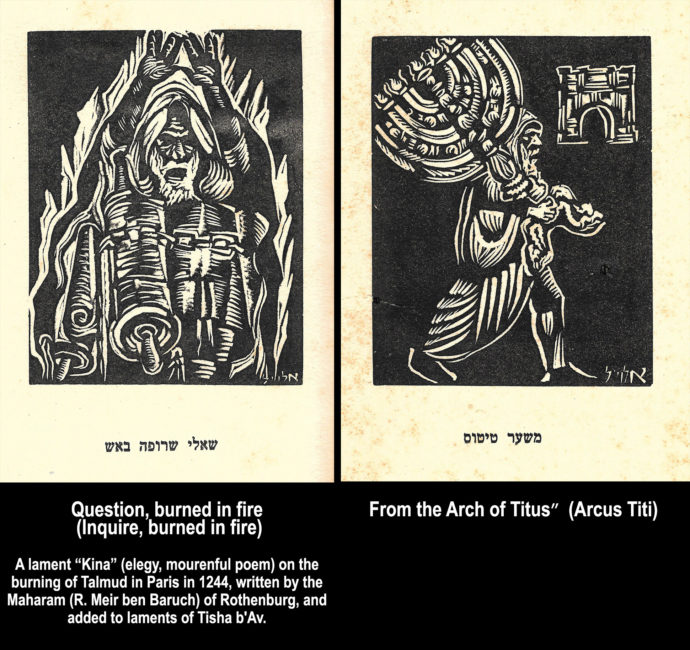

The simple citizen of the land, who stands between father and mother–the book begins with him. The father is stern and God-fearing–a craftsman, with a blacksmith’s mallet in his right hand. And the mother–her face evinces something of the look of the village, which also serves as the background for the picture. This is one of the villages in Eastern Europe, in Poland, Latvia or Russia, a village of low wooden houses built on a plain, which sends its Jewish children to the cheder. There, the youth learns the holy scriptures and dreams about kings, men of war, great priests and the fortress of Zion, and sees in his mind’s eye the Jewish hero descending from Titus’ Arch, unvanquished and carrying the Temple lamp, the menorah, back to his homeland. Then, the long chain of the holy men who sanctified their lives for God’s name, passes before his eyes: the Rabbi who was burned in the fire of the Inquisition with the Torah scroll in his hand, his soul departing with the last word of the “Shema Yisrael”: the believer who resisted with an iron will. The man who carried the House of God on his shoulders from land to land and never let it drop to the ground; the fighter for justice on earth; the man imprisoned awaiting his death sentence. Overwhelmed by the things he has read and seen, the youth wanders back and forth from the cheder to his home, passing through the sordid and dark village streets, the lamp in his hand. Suddenly, the village of his birth flashes before his eyes in a great conflagration that illuminates all of the calamities over the centuries, as if they are unfolding in the present moment. Yet the Jew is deprived of justice as before, while the senseless raging evil, embodied this time in the form of a ludicrous village despot, roars victoriously. The evil act that the youth witnesses leads him to the realization, the recognition of the sole possible response: the “hachsharah,” the training for labor in the Land of Israel. He thus crosses the border and sails the sea, until at last he looks out and sees the glistening rays of the dawn twinkling before his eyes on the shores of the chosen land. Could he possibly be an illegal immigrant? He throws himself into the water and swimming, reaches the land where all of his hopes reside. A few of his friends find their deaths in the ocean depths. The mother, the “birthplace,” takes us in angrily, and despite this, she is the mother, the only one, the savior, blessed be she… and the man returning home kisses the Temple wall and the sacred soil!

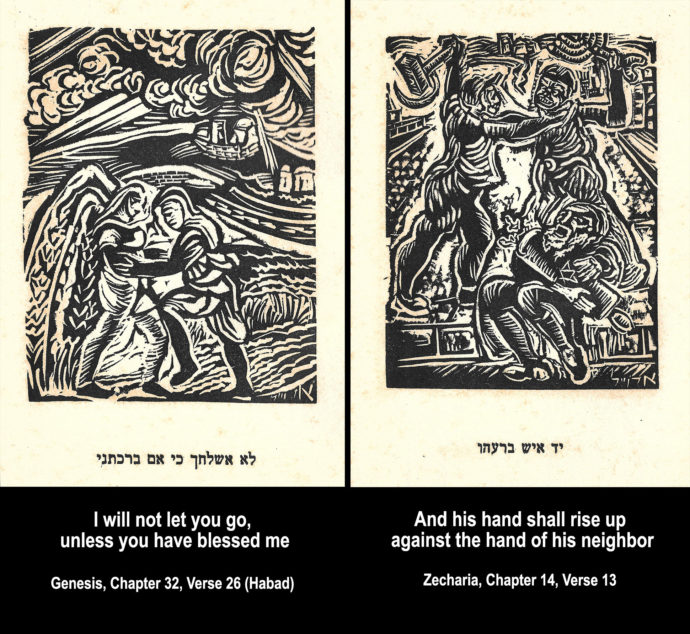

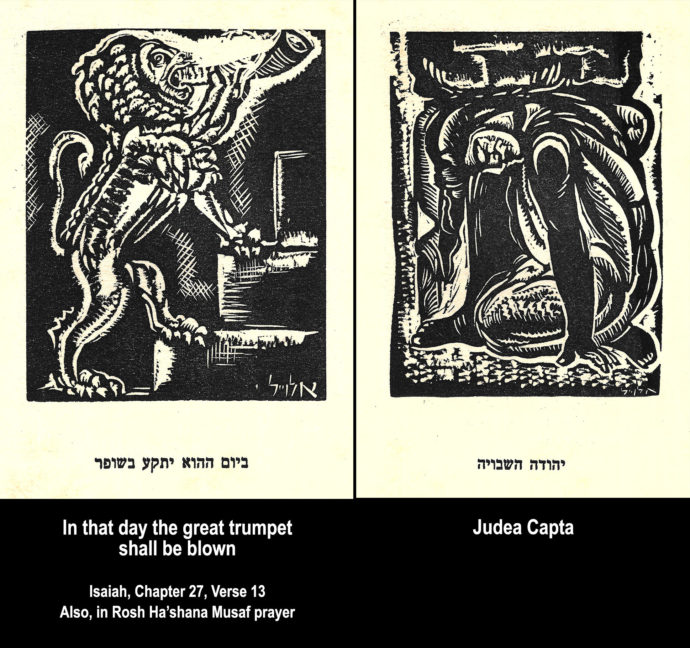

The first disappointments – the nation split into infighting factions, as in the days of the destruction of Jerusalem. And yet, today our will is stronger than ever, and the longing for unity so powerful and more passionate, that we will not relent from the angel of our land “until he blesses us”–a wrestling for the redemption of the soil, in the dust and heat of the paving of the roads, in the working of the land and the establishment of home and family. The first foundation of modest and honest happiness is laid, and already the terrible monster appears, the angel of damage and destruction, with all the signs and symbols of the powers of evil that rise up against us, and with the snake, the lie and the age-old defamation that issues forth from his mouth. The desert rebels against the undertaking of restitution and human dignity–the worldwide battle–that is never ending. But just as the house has been established, and the tower finished, immediately it collapses, and the warriors, in their deaths, raise up that for which they have fought: the symbol of peace–the plough. One of the fallen, faithful son of the birthland, becomes a link in the chain of the martyrs and his grave joins theirs. His death breaches the narrow divide between annihilation and eternal life, feared only by the timid and faint-hearted man. “Judea is captive,” but in the ear of the brave-spirited man, the staccato blast of the shofar bursts forth and rises up, for the Lion of Judah has now arisen and stands erect, in his palm he holds the horn of life, never to release it from his grasp again. From the death sacrifice of the individuals, the unity of the many arises. When the battle is over, a new community is fluttering in the sunlight–orchards, gardens and fields emerge, bubbling up. The desert is pushed back step after step, the primeval, cruel enemy flees from the Phoenix soaring high above the houses of the new capital and heralding the redemption.

And so may it come, speedily in our days! Innocently, the artist led us from page to page, inspiring us with a dream, similar to the dream of his young hero in the cheder. That very dream of the greatness of Israel, the triumph of good and of the power of the spirit over the cruel, unparalleled persecution. Yet, there is a difference between us. That young man, the pupil of the cheder, saw in his dream visions of the past, while we, dwelling in the Land of Israel, dream of the future. And we are already creating it with eyes wide open and awakened.

Max Brod

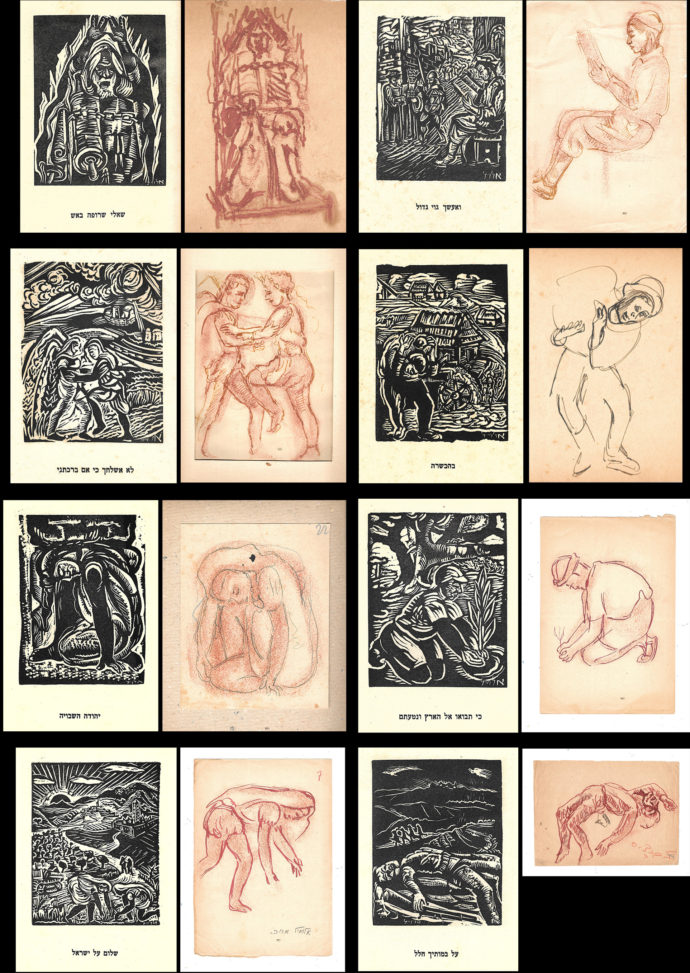

Preparatory drawings, mostly in pencil and sanguine chalk (conte crayon?), are shown paired up with finished linocuts in “Anonymous Jew.” (Photos of the drawings courtesy of the Estate of Arieh Allweil)

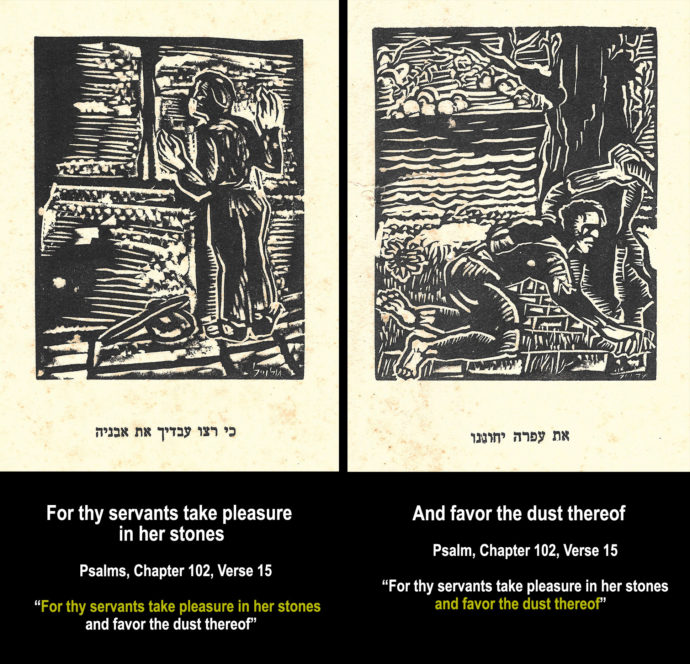

The Linocuts of Anonymous Jew

Once again thanks to Nava Rosenfeld–no doubt with consultation from her sister Ruth Sperling, for translating the captions under the 32 linocuts in Anonymous Jew. The images are presented in the order that they appear in the book, and in keeping with the Hebrew tradition they are presented from right to left.

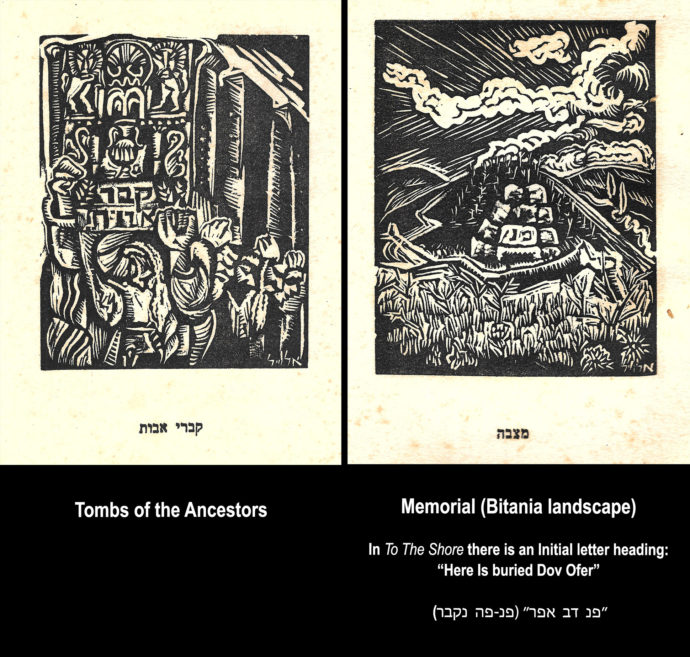

The image with the caption “Slain upon thy high places” refers in general to the deaths of Jewish warriors. But in my opinion, it may specifically refer to the death of Dov Ofer, a friend of Arieh Allweil’s and fellow member of the Bitania Illit kibbutz. And the grave site illustrated in the linocut (right) below shows the initials in Hebrew that reads “Here is buried.” (To find a fuller account of this tragedy, go to my Tura Afora post. LINK)

The image with the caption “Slain upon thy high places” refers in general to the deaths of Jewish warriors. But in my opinion, it may specifically refer to the death of Dov Ofer, a friend of Arieh Allweil’s and fellow member of the Bitania Illit kibbutz. And the grave site illustrated in the linocut (right) below shows the initials in Hebrew that reads “Here is buried.” (To find a fuller account of this tragedy, go to my Tura Afora post. LINK)

Comments

Your comments are most welcome. Please send then directly to me at–p1m1@comcast.net–and I’ll add them to this post.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/ariel-allweil-anonymous-jew/trackback/