Arieh Allweil: Tumultuous Suite of lithographs

Introduction

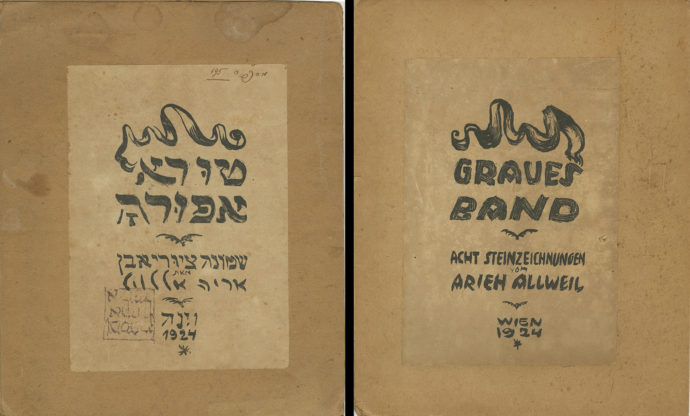

Twenty-three-year-old artist Arieh Allweil created a remarkable and in someways terrifying portfolio of eight lithographs in Vienna in 1924. By that time he had already been a refugee from post-World War I pogroms, an activist in a Zionist youth movement and an early “Halutz,” kibbutz agricultural pioneer. Much about the portfolio–Graues Band (German) or Tura Afura (Hebrew)–is open to interpretation. Even the meaning of the title can be argued.

Prof. Shula Keshet in her essay on the portfolio in Galia Gavish’s 2011 book Arieh Allweil: From Bitania to Vienna and Back (Uri and Rami Nechushtan Museum, kibbutz Ashdot Yaakov Meuhad, Israel) said the suite “describes the first holocaust of the Jewish People embodied in World War I, the pogroms, and the wave of immigration to Palestine-Eretz Israel as an existential decision, but also the disappointment the idealistic pioneers faced in the Land.”

Keshet is one of the authoritative voices that I’ll rely on for interpretations. She is retired professor at the Kibbutzim College of Education in Tel Aviv, teaching Kibbutz literature and Jewish cultural studies. Another authority is Dr. Galia Bar Or, historian of art and ideas, independent curator and former director of the Mishkan Museum of Art, Ein Harod, and author of the book Arieh Allweil: Letters, Figures, Landscapes, 2015. And fortunately Allweil’s daughters–Ruth Sperling, Professor of Genetics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and her sister Nava Rosenfeld, a retired architect–have also shared their thoughts on Tura Afura.

This ART I SEE post is the fourth on the Galicia-born Israel artist Arieh Allweil (1901-1967). This series was begun to create an online presence for the important series of books that Allweil created from 1939 to 1944, most of which were Old Testament stories profusely illustrated with his distinctive linocuts. The first three posts were:

- Introducing the artist with a lengthy bio and a list of his major books. LINK

- The context for the creation of Allweil’s The Book of Amos. LINK

- The page-by-page presentation of the linocuts and translation of The Book of Amos. LINK

While Tura Afura was not a book, I present it as part of the Allweil series because it goes far in portraying the artist’s emotional and philosophical state and puts into context his later book output.

All images of Arieh Allweil artwork are presented courtesy of the Allweil Estate.

Photographs of Tura Afura were courtesy of Galia Bar Or.

(Note, there will be various spellings of some names because that’s what happens in converting Hebrew letters to Roman lettering. And one person would refer to the suite of prints as Gray Tura, another would use Tura Afura.)

Allweil’s life up to 1926

Allweil, born in 1901, grew up in Bobrka (Bobroysk), Galicia (now in Ukraine). His father was a metalsmith. In his autobiography in the 1955 book Allweil, he wrote, “Cheerfulness rules in my house, which was full of work, from sunrise on.” World War I destroyed those idyllic days. He wrote: “When the First World War broke out, the old world of the ‘Austrian idyll’ finished ‘The gods had begun to thirst for blood.’ ” His family fled Galicia “when the Russians invaded.”

The exodus brought him to Vienna, where seeds were planted for his future as an artist and as an ardent Zionist. He wrote: “Arriving in Vienna, the European city, I saw the last glimmerings of the sinking kingdom, and I saw for the first time libraries, museums, theaters and concerts. I joined the youth movement, Hashomer Hatzair and this brought me back to my people.”

(Jewish Virtual Library website (link) states: “Hashomer Hatzair, the initial Zionist youth movement, was founded in Eastern Europe on the eve of the First World War.”)

An arrow points to Arieh Allweil in this 1920 photograph in Venice of Hashomer Hatzair pioneers about to emigrate to Eretz Israel. (Photo courtesy of the Allweil Estate)

But by 1919 he returns to Bobrka to establish a branch of the Hashomer Hatzair. A year later he emigrated to Eretz Israel (Mandate Palestine) and helped found the Bitanya Illit kibbutz. There he became a “halutz.” But despite his enthusiasm for Hashomer Hatzair, he soon realized that his future was to be a painter not a farmer. In Allweil, he wrote: “I decided to become a painter at the time when I was living in a settlement of pioneers on a mountain in Galilee.”

Two traumatic deaths might have influenced Allweil’s decision. The first was the death of a friend. Galia Bar Or in an email wrote: “For Allweil Dov Ofer’s death was a trauma that he never shook off because Dov Ofer had acceded to his request and set out to a meeting in Tiberias instead of him, armed with a revolver that didn’t work. The nagging thought that his comrade had been killed instead of him, and that his death might have been prevented had he gone himself, armed with his reliable English rifle, gave him no rest.” In his autobiographical essay in the book Allweil, Allweil wrote: “My good friend, Dov Ofer, went in my place to Tiberias, and did not return. We found him, bleeding from a robber’s bullet.”

Bar Or in her book said: “Allweil was already known for ‘trying his hand’ at painting, otherwise the difficult task of designing the tombstone would not have been given to him.” In Alweil’s 1939 wordless narrative The Anonymous Jew he included a linocut of tombstones to fallen comrades like Dov Ofer.

In her book Bar Or described the linocut: “Allweil depicted a view of Bitanya … with a lopped tree trunk in the foreground and behind it a memorial mound of stone, at the center of which is a broad stone panel with the Hebrew letters P.N. [initials of the Hebrew words for “Here lies” (literally, “Here is buried”) (Tr.)] engraved on it. This is a large memorial mound; its face almost covers the silhouette of the mountain behind it, the Bitanya Ilit ridge; equally emphasized is the restless sky.”

The second traumatic death was the suicide of Natan Ikar, just two and a half months after Ofer’s murder.

While Keshet, in her essay, wondered about Allweil’s decision to leave the kibbutz–”The surprising decision by a respected leader, a pioneer–a halutz–to return to the Diaspora, abandon all activities of his movement–Hashomer Hatzair–and devote himself to the life of an artist, remains a mystery”–she then described some of the tensions and events that roiled kibbutz life and may have pushed Allweil to seek a life as an artist. She wrote: “During the day the comrades removed boulders and rocks from the mountain, dug holes for planting olive trees and prepared the soil for vineyards, and at night, devoted themselves to the ritual of confessional talks, hoping to thus bring about reformation of themselves as individuals and the world alike.”

Relying on descriptions of confessional talks in David Horowitz’s book My Yesterday (Tel Aviv and Jerusalem: Schocken Books, 1970), Keshet wrote: “The individual would be held up to criticism and constant judgment by the social group, which had no hesitation in exhibiting mental cruelty. These confessions became scenes of public exposure, collective undressing of the psyche, with painful scenes of hysteria. The tension reached extreme heights with the suicide of Ernst Pollak, known by his Hebrew name of Natan Ikar. The affair reached a dramatic conclusion as the interpersonal tension bubbled up to the surface to become open warfare during the Shomria camp, between those who felt that Meir Ya’ari was taking the right path, and his opponents headed by David Horowitz. After a long and difficult nighttime discussion, Meir Ya’ari left the group with his wife, Anda.”

In an email Bar Or gave a differing account. She said that Ya’ari “claimed that he did not know anyone by that name, and also hadn’t heard of the case of suicide in Bitanya Ilit that was associated with this name. In fact, Natan Ikar was not a member of Bitanya, and did not participate in their conversations.” Instead she detailed Natan Ikar’s stay in a Safed hospital for severe illness and the use of a drug for syphilis. And she said he wrote letters expressing mental and financial distress. Furthermore, she wrote: “It’s also possible that Allweil himself didn’t really know him and was only asked to design the tombstone, on the assumption that he had become something of an expert at this.”

Allweil’s tombstone for Natan Ikar reads: “Natan / Ikar / Committed suicide on 5 Kislev 5681 [16 November 1920] / His comrades.” But the word “suicide” on a Jewish tombstone might have led to it being vandalized. Bar Or wrote: “Allweil’s daughter recounts that when she visited the cemetery in Kinneret with him, years ago, he pointed to Dov Ofer’s tombstone, shared with her his distressing memory of his comrade who had been murdered, mentioned the other tombstone he had designed there, but was unable to find it. A rumor had gone around that farmers from Kinneret had vandalized the tombstone and it’s even possible that members of Kibbutz Kinneret, too, preferred to keep it hidden. Could it be that some dark story is concealed behind Natan Ikar’s tragic death?”

According to Bar Or: “Allweil’s engraving on Natan Ikar’s tombstone was rediscovered in 1991, 70 years after it was erected at the cemetery in Kinneret, by a relative of the deceased…” She then offered this description of the image above the tomb’s text: “The drawing spreads over the central and the upper part of the stone in a meandering line, out of which the figure of a visionary creature seems to emerge. Only details of its face–eyes, nose and mouth–are emphasized in black, blending a dread of death in the open and empty eye holes with a strong and sensual life force of creativity and imagination. The flashes of lines and forms that cohere into a kind of winged insect or long-bodied bird, blend the animate, the vegetal, and the inanimate.”

It’s hard to describe the tombstone’s image other than a nightmare. Keshet asked: “Are the nightmares of Tura Afura indeed the nightmares of Bitanya? Allweil, who had been the leader of the Hashomer Hatzair club, or ‘ken,’ in Vienna before Meir Ya’ari, was critical about the latter’s leadership style…. Allweil also objected to the cult of confession, and violently opposed to the public exposés that dominated the group under the influence of Ya’ari’s charismatic personality.”

While Keshet said “as I see it, it was not these facts that determined Allweil’s artistic choices,” kibbutz unrest and the death of Natan Ikar following the death of Dov Ofer might well have been instrumental on his change in direction: to focus on becoming an artist and seek instruction in Vienna.

The artist’s daughters, Ruth Sperling and Nava Rosenfeld, wrote in an email: “We doubt if these [deaths] affected his decision to leave Bitania. He left for Vienna because he decided to be a painter, which required further study (in Vienna), yet it was clear to him that he is coming back to Eretz Israel right after completing his studies at the Vienna Academy, which he did.”

Bar Or wrote: “He may have left for Vienna with the goal of returning to Palestine and being a painter in a collective settlement–or, when he left he may have already given up the dream of the collective and the movement, which as we know had guided him since his early youth. Did the dream fade in the wake of a personal disappointment or an ideological disappointment?”

From 1921 to 1925 Allweil studied at Kunstgewerbeschule, a prestigious art academy in Vienna. In her book Arieh Allweil: Prints & Caligraphy, Books 1939-1949 (The Isaac Kaplan Old Yishuv Court Museum, Jerusalem, Israel, 2007), Galia Gavish said, “By the time that Arieh Allweil came to study at the academy, the German expressionist stream had already taken hold…. After WWI, many of the artists returned from battle, shocked and unable to break free of the horrific sights. They were opposed to wars and dictatorships and in favor of hard-working laborers. Their world view suited that of Arieh Allweil, and he was quickly accepted by them to the Kunstschau group and even exhibited with them.”

And in her book Bar Or wrote: “…in 1924 he joined the avant-garde Kunstschau group–a circle of artists that had originally formed around Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele. Most of the members of the group were older than him, had already been active in the art world for some time, and were known on the art stages throughout the world. They received him, the only Jew in the group, into their circle and their discourse; they gave him their trust and included him in their activities. He stayed there for four years….”

Arieh Allweil, in his own essay in Allweil, said, “In 1924 I exhibited for the first time with a group ‘Kunstschau’ who accepted and encouraged me…. Once a week I visited a rich art-lover Neumark with this group and he helped me go to Paris, but the costs of my studies were borne by my parents…. In 1925, I exhibited in an exhibition of Austrian Art of the quarter century, and at the time I published a folio of lithographs with the name ‘Grey Ribbon.’ ”

Ruth Sperling, the artist’s daughter, doesn’t believe the Tura Afura suite was exhibited in that Vienna exhibition. Instead he showed five oil paintings, one of which was reproduced in the catalogue.

“In 1926, I returned to Israel by way of Paris and Italy,” Allweil wrote in his essay, “and I was on a ship again. The smell of tar and sea water reminded me of the pioneer songs of my first emigration–just as the pleasant smell of linseed oil reminded me of the 9th symphony of Beethoven, which I heard for the first time on entering the art academy. I did not remain in the Kvutza [a communal settlement] to work the land–would I at last realize my dreams from Bitanya about painting?”

Exhibition, article history

As far as his daughters know, Arieh Allweil did not exhibit Tura Afura in Israel, i.e. from the time of independence in 1948 through to his death in 1967. In an email Sperling said: “We did not see it in his life,” and added, “Nava and I don’t know why my father never exhibited Tura Afora in Israel, nor did he speak with us about it.”

To the best of the daughters’ knowledge, Tura Afura was first shown in Israel in 1998 when Tally Tamir was curating the exhibition “Shabbat in the Kibbutz 1922-1998” at the Ashdot Yaacov Museum, celebrating 50 years of the State of Israel. Sperling wrote: “She approached Nava, asking for works of our father concerning the Kibbutz (Bitania Illit group, the founding fathers of the Kibbutz movement). Nava showed her Tura Afura, and she exhibited it.”

In an article–”Sabbath in the Kibbutz or the Kibbutz as Parable”–for Jerusalem Review (1998/9, Vol. 3), Tamir said: “Arie Alvail [sp]–the only painter who was a member of the Bitania Ilit group–the founding father of the kibbutz movement–provides the earliest, and perhaps also the hardest and almost nightmarish, painted testimony from the first pioneer era, a testimony suppressed by him and for many years not exhibited in public. Mukie Tzur, a researcher into the period of the Bitania Ilit group, deduced from Alvail’s work the possibility of returning to the ‘rebellious and experimental component’ which existed in the early kibbutz. Together with Meir Levavi, one of the kibbutz Rehavia pioneers, Alvail expresses the dissenting voice of a pioneer who was then, and remains today, outside the general consensus.”

In the catalogue for the exhibition, Tzur wrote that [in Sperling’s words] “the order of prints is not important. He saw it as a Growing-Up novel in prints describing a personal voyage of a pioneer, full of expressive images of stations of his life, and his struggle with the turmoil of life. He wrote that Allweil had chosen an internal voyage, using allegoric figures and metaphoric situations. Mukie also talks of the legendary group of pioneers in Bitania and about the rebellious and experimental component in Tura Afura. He also finds a connection between the grave yard lithograph of Tura Afura and the tombstone of Natan Ikar, which Allweil created, in which he saw the rooster of atonement and the mosquito of despair, the latter appeared in the literature of the period as pecking in the fevered minds of the pioneers.”

The Allweil daughters met Shula Keshet in 2009 when she lectured on her newly published book The Genesis Point: The Incarnation of the Bitania Myth in Hebrew Literature. Sperling said: “Mukie Tzur, who was a speaker at that meeting, introduced us to her. On that occasion we talked with her about Tura Afura and the connection with Bitania.”

When Tura Afura was next exhibited in 2011, Keshet wrote an essay in Galia Gavish’s exhibition catalogue, Arieh Allweil: From Bitania to Vienna and Back. Keshet then published a fuller article in Cathedra 145 entitled: “From Bithania to Vienna and Back: A New Look at Arieh Allweil’s The Gray Mountain Prints.” Quoting an English abstract of that manuscript, Sperling wrote: “Prof. Keshet thought that previous interpretations of Tura Afura as referring to the tense atmosphere of the confessional conversations held in Bitania were not substantiated. She thought that Tura Afura relates to the pioneers’ story as influenced deeply by the tremendous shock caused by World War I, especially the pogroms inflicted upon Jews. Bitania is the last symbolic stop. Tura Afura is the narrative of the wandering Jew who finally reaches the shore, the place of redemption, only to find even there death and bereavement.”

Lastly, Dr. Galia Bar Or wrote the book Arieh Allweil Letters, Figures, Landscapes (Mishkan Museum of Art at Ein Harod, 2015) as a retrospective of Allweil’s life and work.

Arieh Allweil, “Bitanya Illit,” oil on cardboard, c. 1920, 35.5 × 49 cm (14 x 19.3 in.) (Photo courtesy of the Allweil Estate)

The Title

As translated in Allweil’s autobiographical essay, the title–Graues Band in German and Tura Afura in Hebrew–of his suite of lithographs reads “Grey Ribbon.” But his daughter Ruth Sperling thinks the title might also refer to the mountain that rises above the kibbutz Bitanya Illit, as shown in Allweil’s painting (above). In an email, she said;

“It is not clear what the name Tura Afura means. In German it is Gray Band. In Aramaic ‘tura’ is a mountain, ‘afora’ is gray. The gray mountain could be Bitanya. It could also be translated to the Gray Range . It could be either or both Gray Mountain and/or Gray Range. Gray Mountain was interpreted as the gray Mountain of Bitanya, and Gray Range as the pioneers struggling on the Mountain of Bitania. The few images of our father of Bitanya always portray a dark mountain. Also, the only oil painting of Bitanya by our father is of a gray mountain.“

Galia Bar Or decided to concentrate her remarks on the German title, although she noted: “As to the title Tura, Tur in Hebrew is a rank, band, row, column, file. Adding the letter a changes to female.”

“The German title of the series Graues Band,” she said, “has a connotation of dread, because of the linguistic proximity of the words for “gray” and “horror” (the noun “Grauen”). Dread seems to be present in all of Allweil’s works, beneath their veil of tranquility–a dread that would turn into profound and agitating shock with the arrival of news about the horrors of the Holocaust–but always beside feelings of renewal and hope, as a structured polarity.”

Shula Keshet in her 2012 essay wrote: “Allweil called the collection ‘The Gray Collection’ (graues band). In German, there is a linguistic association between the word graue (gray) and the verb ‘grauen,’ whose meaning is associated with terror, fear. The name of the collection in German therefore has no clear connection with Bitania’s “mountain.” She then referred to Allweil’s autobiographical essay. [Here I used the translation in the Allweil book.] “When the First World War broke out, the old world of the ‘Austrian idyll’ [was] finished. ‘The gods had began to thirst for blood’ …. The hills and the rising and setting sun did not belong to me anymore. I received my first history lesson.”

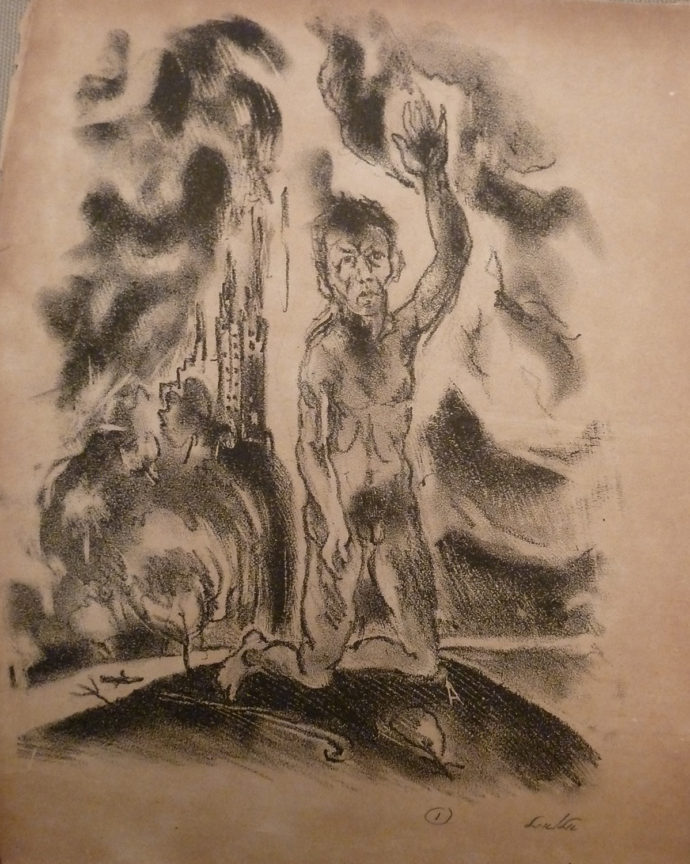

Arieh Allweil signed this light from “Tura Afura” and circled the number 1. (Courtesy of the Allweil Estate)

Tura Afura

I asked both Galia Bar Or And Shula Keshet to discuss the eight plates in Tura Afura and, if possible, to place them in sequence. The portfolio was published without an index (at least none have survived), so the order that Allweil intended is not truly known. However, Ruth Sperling emailed the above image and wrote: “I just wanted to point your attention that, although we don’t know the order of the images in Tura Afura, in Nava’s collection the image you marked as No 1, has also an encircled 1, and Allweil signature in Hebrew made by my father.” she added: “Nava and I think the face might be the face of our father. We are not sure.”

Dr. Galia Bar Or first presents her thoughts on the suite, followed by Prof. Shula Keshet. The words are those of each author.

Allweil’s daughters–Ruth Sperling and Nava Rosenfeld–added a comment Bar Or’s interpretation of the graveyard image. Their thoughts are in italics.

Galia Bar Or

Given the lack of archival materials, such as sketches and preparatory exercises, it is difficult to determine the order of the prints and the specific sources of inspiration. It may be assumed that Allweil left his drawings and sketches for safekeeping in his parents’ home, but everything that was kept there was destroyed in the Holocaust. Likewise, many of his early paintings were lost in the studio he had in East Jerusalem, which remained in Jordanian-held territory when the city was divided in 1948.

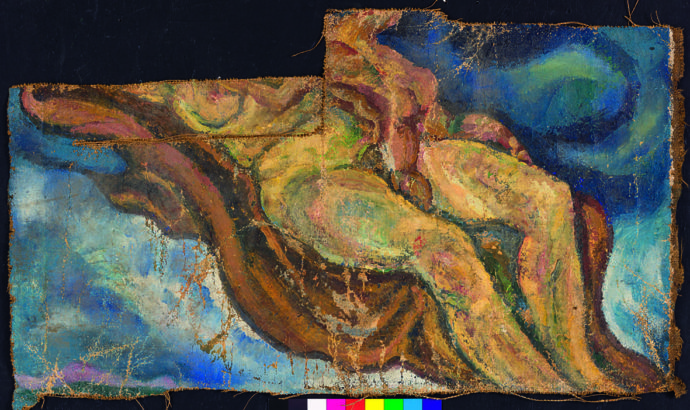

We can get some idea about Allweil’s early sources of inspiration and ways of working from an early painting that has survived, which he painted after one of the masterpieces in Vienna’s museums.

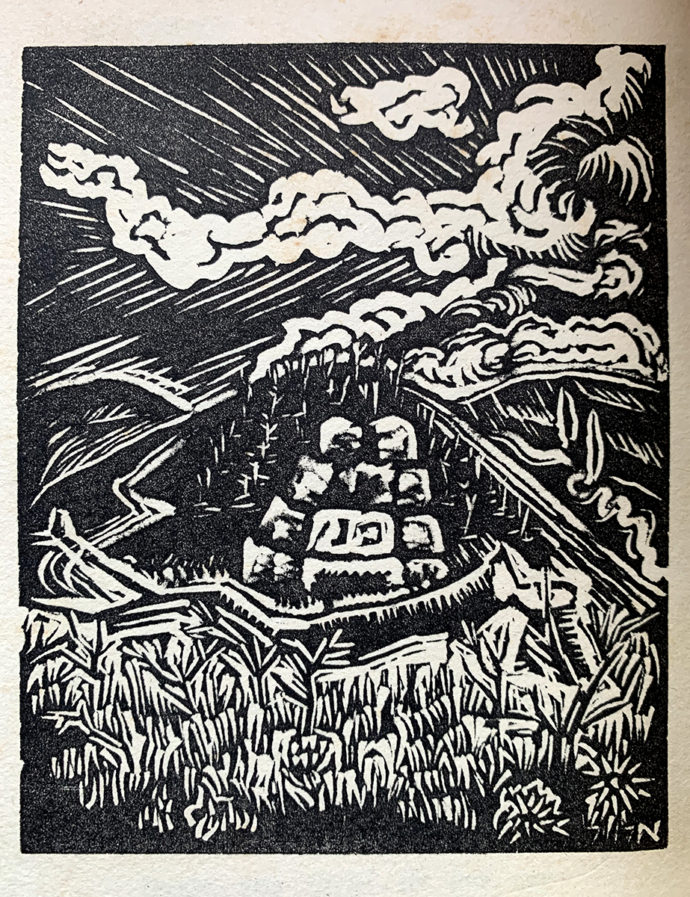

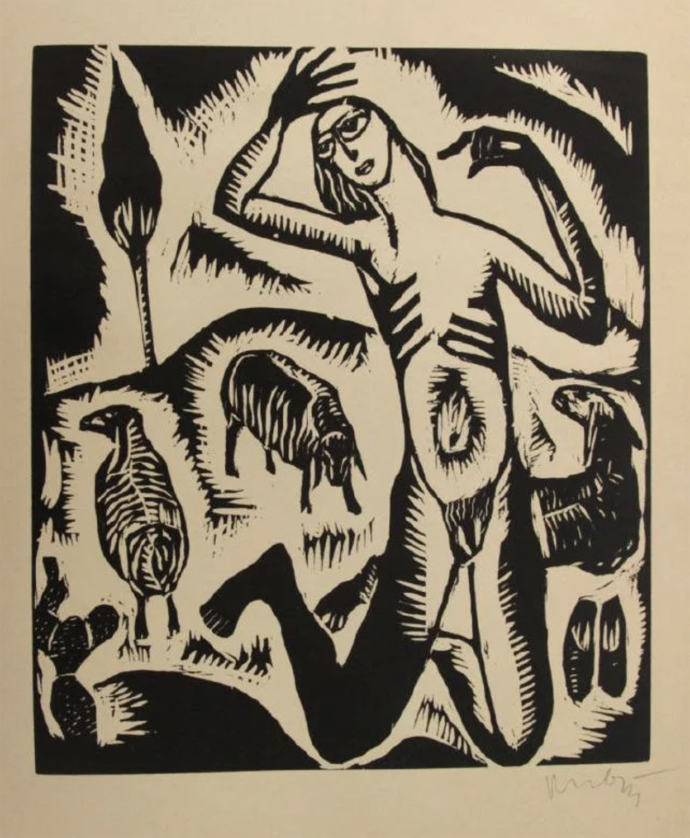

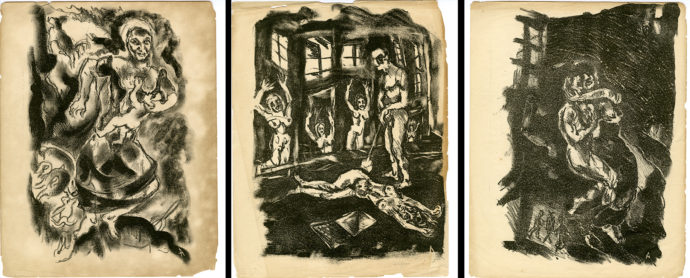

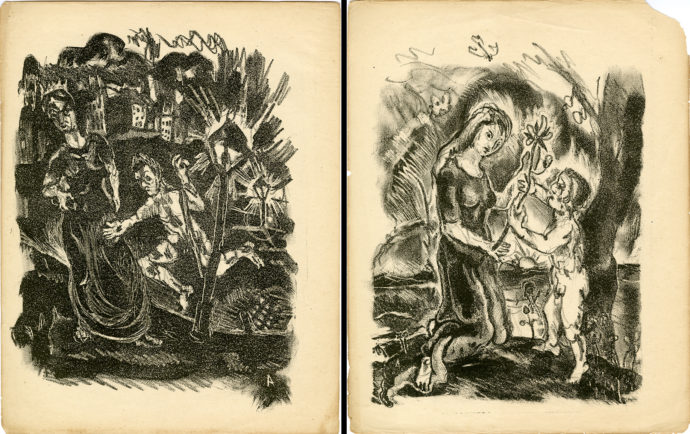

Arieh Allweil lithograph from “Tura Afura,” signed in the image with the initial A. The sheet of paper measures 32 x 25 cm or about 12.6 x 9.8 in.

A comparison between a segment of this painting and the Gray Tura series may give some indications of how he worked. In the lithograph, the rich painting in oil on canvas was converted into a free tonality, while the sensuous and elevated character of the reclining female nude in the painting, with the infant pressed to her breast among the curves of her body, was converted into a terrible picture of horror: a mother fleeing with her baby from a place of smoke and ruins, with a three-pointed stake that symbolizes the fear of death.

This print brings to mind other paintings by artists of that time who were influenced by the First World War and the pogroms. The animals fleeing in the background, seemingly dispersing in all directions, refer to Chagall and in style resemble the work of Lazar Segall, who was known and esteemed in that period. The rich painting with all its mannerisms–like folds of a pampering bed of soft fabrics, with the glow of the agate light in the deep sky–has therefore been replaced in the Gray Tura print by the touch of ashes, which seems to have gathered and piled up in the folds of charred ground as smoke rises in the background.

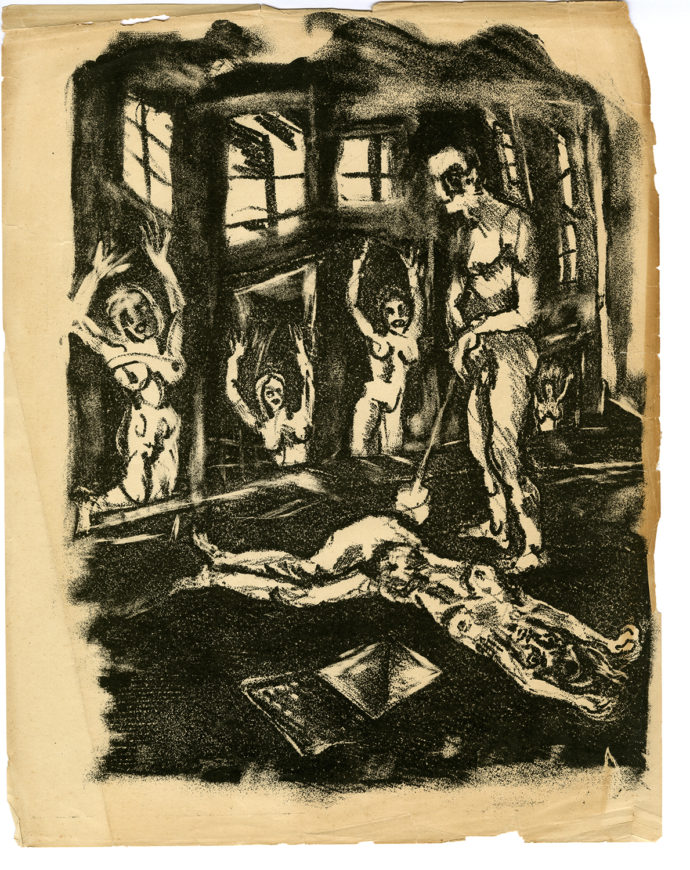

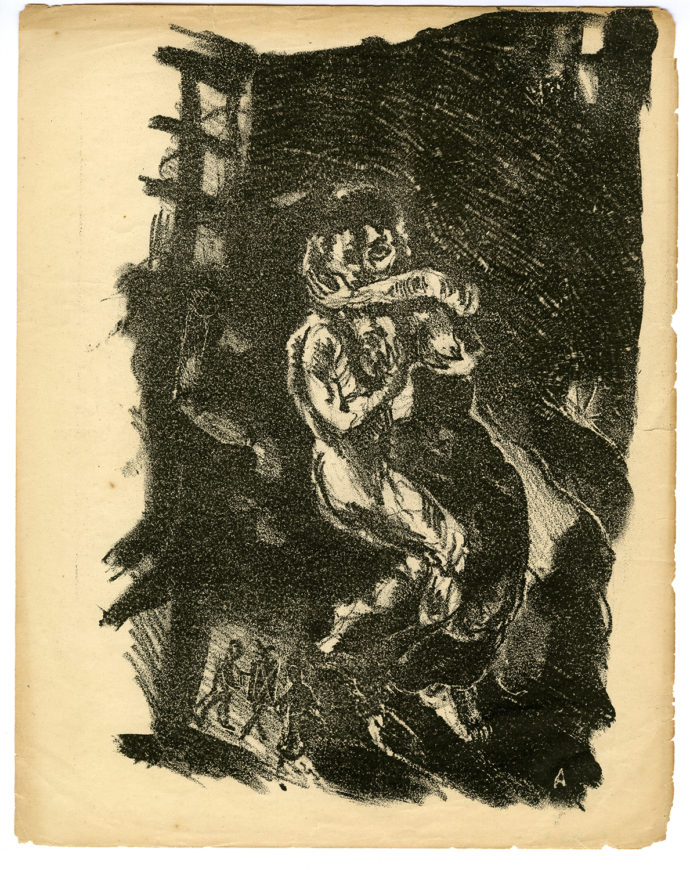

Another print probably belongs to this phase of response to pogroms and the outcry of pain and loss. It shows lamenting naked women standing or kneeling opposite a naked man, who is burying the corpse of a woman whose arms are stretched out. An open book lies on the ground beside her, and in the background is a ruined house, its barred windows torn into the open space.

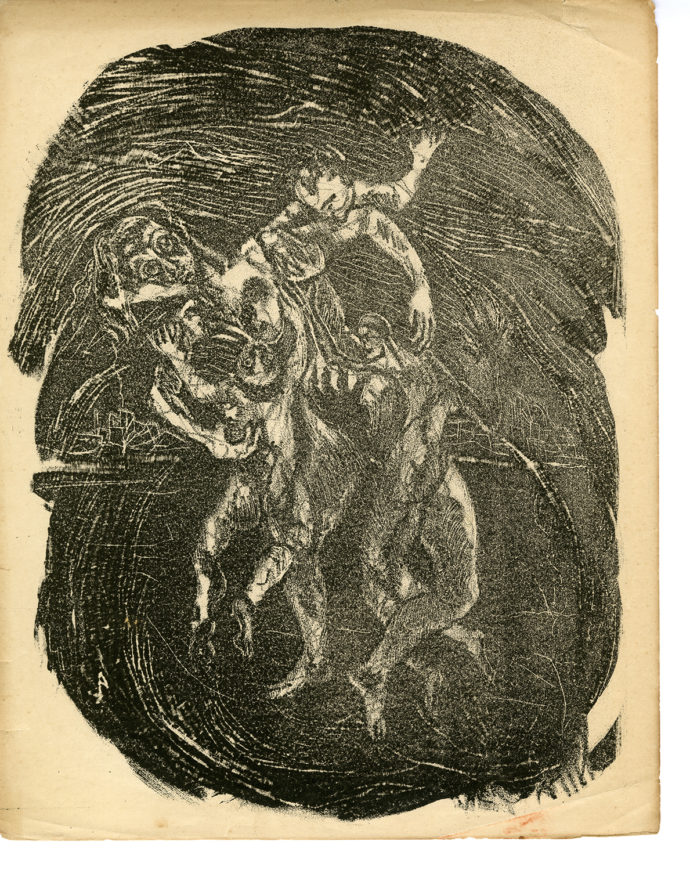

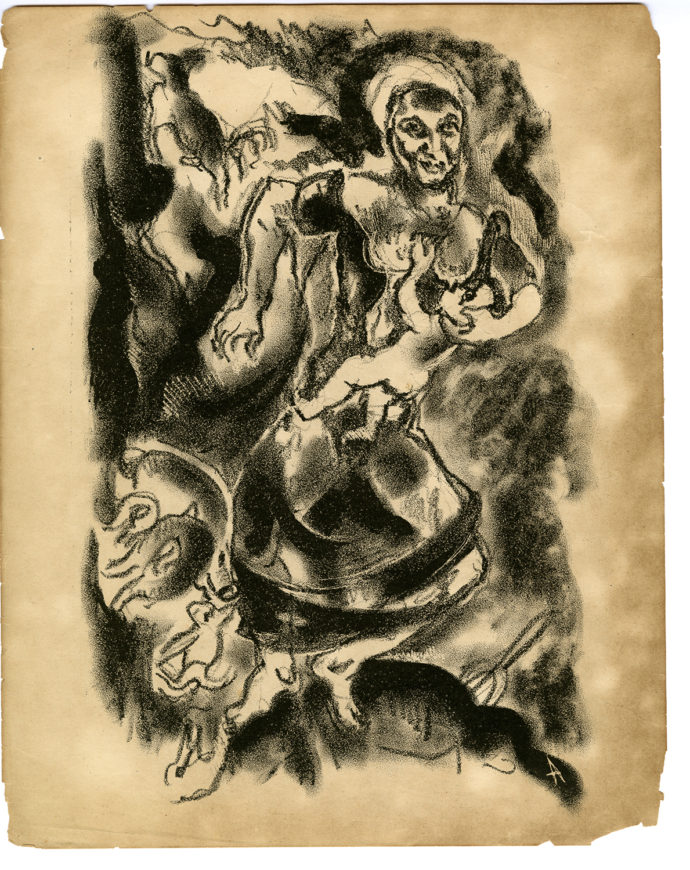

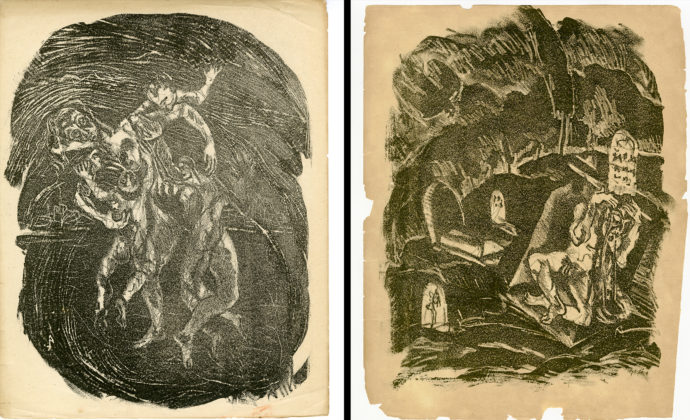

In another print we see a woman, perhaps an allegorical figure, with an overgrown baby pressed to her breast and other bodies clutching and sucking the marrow of her falling body, as though she were already a ghost. The fascinating choreography of the clutching and the twisting responds to the structure of the background, which is done as though with a single free brushstroke that imprints spiral movements in the thick black ink.

This sense of clutching and twisting recurs in other prints in the series, for example in the embracing couple at the ruined house with barred windows; this time the man is naked and the woman is wearing a long dress. He clasps her breasts and she embraces him, her open eye looks straight ahead in a troubling look. Again there are enigmatic images with the house with barred windows in the background. This ambiguity seems to unite layers of images and sensations, unarticulated insights about the masculine and the feminine, animus and anima, Jewry and Diaspora, myth, allegory and dream.

The allegoric dimension emerges principally in the pictures of the big women, where the men kneeling before them are half their height, or are handing them something. The allegoric tone sends us to a historical depth of images that recur throughout the centuries–perhaps a reincarnation of the relations of “Synagoga” (the synagogue, Judaism) and “Ecclesia” (the church, Christianity), images from the anti-Semitic Christian iconography that centered around the image of the “Great Knesset” (the “Great Assembly”), which according to Jewish tradition was set up with the return to Judah of exiles from Babylon.

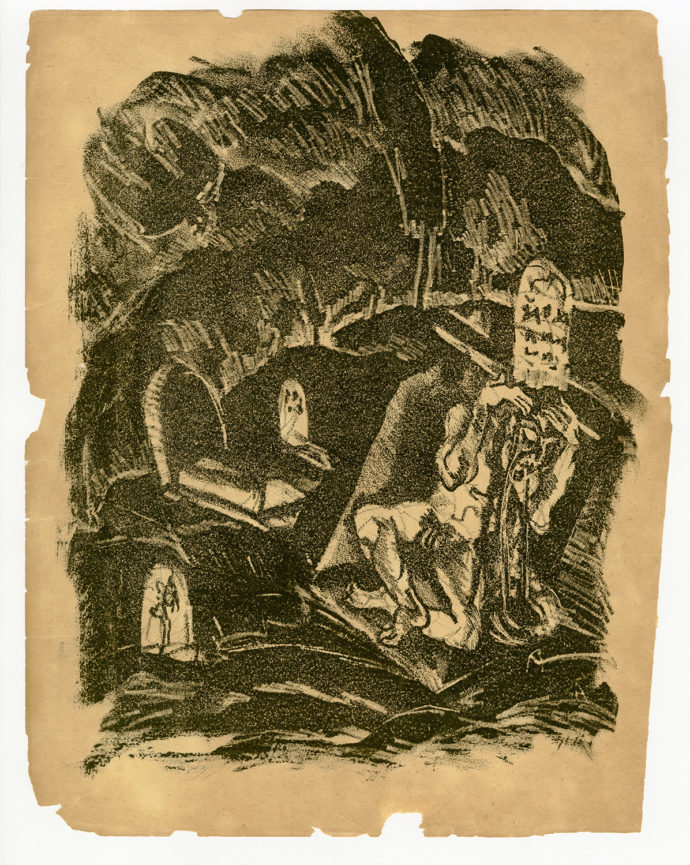

The “Great Knesset” (the Lady or the Matronita*) appears on another page (left above) of the series holding a scroll. Depicted beside her is a man holding a staff, with a victor’s wreath on his head and on his hands one can identify the stigmata of Jesus.

* Matronita derived from the Latin word “Matrona,” meaning “respectable lady.” In Jewish culture the Matronita is a figure of a foreign woman, who appears in various “midrashim” (study, commentary, sermon) in many forms and symbolizes the people of Israel. She is often a character in parables.

Some scholars identified this cemetery as the renown cemetery of Kinneret near the lake of Galilee, where Allweil created a significant tomb-grave. That is because the tree seems to look like a Palestinian cypress that is common in this locality. But a tree just like it also appears in other landscapes that Allweil painted in Europe, and especially in rural landscapes of Bobroysk [his hometown in Galicia], of which he painted many during those years. It’s possible that he connected this imagery with the end of the Exile and also with the vision of the resurrection of the dead, for the Jew sitting cross-legged in front of the tombstone looks like a grave-dweller who is coming to life before our eyes.

Ruth Sperling and Nava Rosenfeld: We think that the Tura Afora lithograph of the graveyard depicts in one grave a figure holding the Satan mask that is reminiscent of the tombstone of Natan Ikar, in Kinneret, and is thus linked to Bitania.

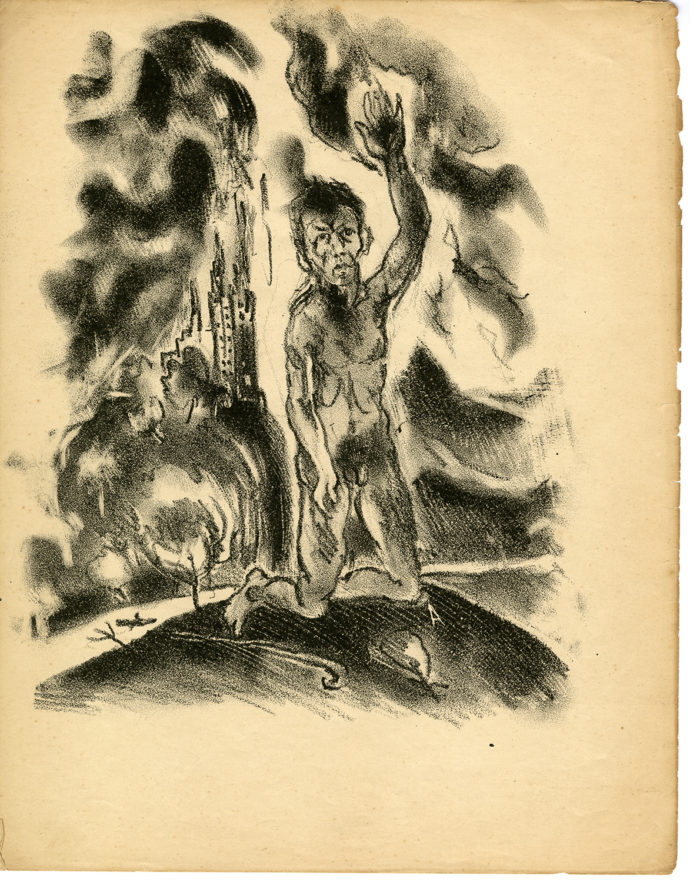

This complexity is revealed in what seems to be a a self-portrait of the artist: He is depicted naked, in full figure, as an allegory that blends a dream with a picture of a fractured reality of destruction and dread. It seems to be related to the figure of the Wandering Jew. The Eternal Wandering Jew of the anti-Semitic myth, which stems from the Middle Ages as the Jew who sinned against Jesus and whose punishment was to wander forever, tormented and persecuted, deprived of everything, humiliated and banished. In the early days of the Jewish national renaissance, the figure of the Wandering Jew was adopted by quite a few Jewish artists who made use of it to relate to their complex identity. Allweil’s Wandering Jew is kneeling, and a sign seems to be imprinted on his raised hand, perhaps one of Jesus’s stigmata. A chain lies at his feet, perhaps a rosary chain, the eyes staring straight ahead, the prominent cheek bones, the lips sketched in the frame of the pointed chin. Behind his back is a vista of Europe going up in flames and the path of a river separating the ridge he kneels on from the burning city behind him.

Another level of dialogue of ideas may be found between Allweil’s kneeling figure of the Wandering Jew and the figure of Moses beside the burning bush in a print by Reuven Rubin that was being distributed at that time, for the wanderer’s staff is also one of the attributes of Moses, the leader who marked out the way from slavery to bondage – an original juxtaposition by Allweil that overturns an iconic form of Jewish collective memory.

Allweil seems to have been discussing the wandering and the vicissitudes of the Jews in their symbiotic and catastrophic relations with decadent Europe, an experience of generations that found strong expression in the aftermath of the First World War.

Allweil’s album represents disparities and tornness and inner conflict more than a striving for a unity and balance of idea and feeling. This is the power of this series, which expresses dread and loss beside what seems to be a yearning for redemption and resurrection. A generational identity, it is commonly thought, is shaped during adolescence in the wake of significant events such as a war or a revolution. In these terms, the generational identity of Allweil and his comrades, which is characterized by its sense of an end, was shaped through the wave of pogroms that occurred both before and after the First World War, particularly in Ukraine, where they expressed the dark side of the Ukrainians’ aspiration for national self-determination. Hundreds of Jewish towns were attacked in the organized pogroms of army regiments led by [Symon] Petliura; tens of thousands were murdered, and acts of rape and terrible cruelty took place. In their wake a massive movement of emigration of Jews began to countries all over the world, and the few who migrated to Palestine.

Shula Keshet

Allweil had named the collection in German Graues Band (“The Gray Row”). According to my thesis, based on other works of the artist, including his Bible prints, the story of Tura Afura tells the big story of Jewish Time: diaspora, persecutions, pogroms and finally, redemption. Coming back to the homeland, to Eretz Israel, had been described in his prints as the last stop in the tragic journey of the Wandering Jew.

We don’t know the right order Allweil had wanted to arrange the prints. Mine is a suggestion based on other works I observed. If the story, as I see it, describes the sequence of Diaspora and redemption, I would start with the image of burning Europe (the First World War). On the background is a burning city (high buildings); in the foreground the Wandering Jew is kneeling. At his feet lies his tragic symbol, his wandering stick.

Scenes of horror and death follow (the order is not important): A woman flees from a burning place with a baby in her arms; women screaming out of a burning house and a naked woman lies on the floor awaiting her grave; and a woman holding, embracing a body of man, the last embrace of a lover?

The image of the Synagogue and the Wandering Jew (left): The synagogue with a crown and the Jew with a victorious garland on his head will signal the beginning of the age of redemption. The image of new hope (right): An image of a woman and a young boy presenting her with a flower.

A circle of a Hassidic dance (left). The last image (right) represents the Eretz Israeli graveyard. I identify the cypress tree, an Israeli typical tree. It is not a European place. Allweil was the artist that created the tombstone for his friend’s grave. The new life presented a mixture of new hope but also hard work and new dangers. New enemies threatened the pioneers. Some people, including Alwail’s best friend, lost their life.

Trackback URL: https://www.scottponemone.com/arieh-allweil-tumultuous-suite-of-lithographs/trackback/